Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães discusses the disillusionment that led Modernist painter Joaquín Torres-García to leave New York as well as the city’s lasting influence on his artmaking and his continued ties to North America in this biographical essay. Second part of two.

Despite these exhibitions, his circle of prosperous friends, and his significant connections to artists and art patrons, Torres-García sold little of the work he produced in the United States. The appeal of New York and the glamour of American modernism eventually wore off; his once beloved adopted country and city became overwhelming, a place where a foreigner, facing the pressure to conform to American socioeconomic standards, could not maintain his individuality. “Here all foreigners need to adapt: —which is to earn money no matter what,” Torres-García wrote in his manuscript on New York. “—America is a death trap—there is entry, but no exit. . . . This is New York—the city of 7 million people—which crushes the artist.”1Torres-García, J. Torres-García: New York, pp. 74–75. The fast-paced city caught up to him, as did the cold climate, illness, seclusion, the language barrier, and the lack of a steady income.

Nor was Torres-García successful in his production of wooden toys, the idea that he told Barradas had brought him to New York in the first place. In 1921, in association with an existing firm called Dover Farms Industries, he established a company, Artist Toy Makers, and then in 1924, now back in Europe, a second one, Aladdin Toy Company, which maintained a New York warehouse financed by Force.2Tomás Llorens, ed., Torres-García a les seves cruïlles (Catalonia: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 2011), p. 188. See also Cecilia de Torres and Susanna V. Temkin, “New York: 1920–22” and “Italy: 1922–24,” in “Chronology,” Joaquín Torres-García Catalogue Raisonné, available online at http://torresgarcia.com/chronology/ (accessed July 9, 2015). He also looked for carpentry and manufacturing resources in Italy—his first stop on leaving the United States—and began to market toys on a substantial scale to toy companies in Amsterdam, London, and Barcelona.3Llorens, ed., Torres-García a les seves cruïlles, p. 188. Just when it seemed that the concern was about to take off, however, the warehouse burned down, along with its entire inventory. In 1924, Torres-García gave up the business for good.

Torres-García’s New York manuscript shows that he went back and forth between loving and despising North America. On the one hand he admired America’s cultural diversity, its modern, functional, and utilitarian designs, its gender equality, and the opportunities it offered for success. On the other hand he saw it as a country in which the individual’s ultimate goals were consumerism, commercialism, and industrialism—a place where if one didn’t adapt to capitalism and become its slave, one ceased to exist.4See Torres-García, J. Torres-García: New York; pp. 69–70, 82–83, 103–4, 109, 111–12, 137, 145,147. In 1922, with his toy business floundering, Torres-García blamed himself for being tempted by “that hateful commercial thing” and for his inability to support his family by selling his art.5Ibid., p. 228 Deciding to leave New York and return to painting, he left the city with his family on July 17. Living first in Italy, then in France and Spain, he eventually returned to Uruguay in 1934, where he would remain until his death in 1949.

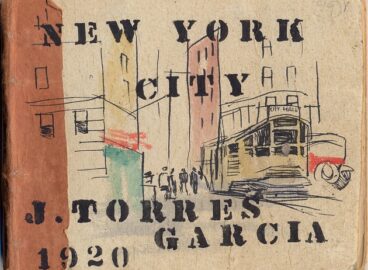

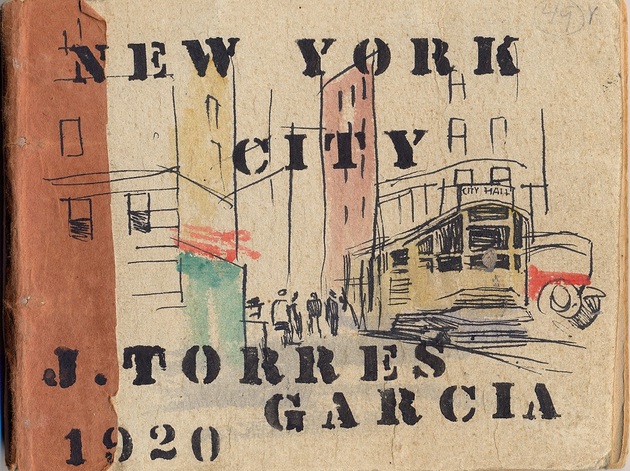

Back in Europe, Torres-García continued to think of New York, and to maintain connections with it, despite the transatlantic distance. In 1926 he exhibited his sketchbook New York (1920) in his first solo exhibition at Galerie A. G. Fabré, Paris; in 1929 he welcomed Dreier to his studio; and in 1932 he made a sale of works to the New York collector Albert Eugene Gallatin. In 1927, Gallatin had founded the Gallery of Living Art, a museum-type space—in 1936, in fact, he renamed it the Museum of Living Art—intended to give an American audience access to the most recent developments of twentieth-century art, and in particular to the work of the School of Paris.6A. E. Gallatin, “The Plan of the Museum of Living Art,” January 1940, in A. E. Gallatin Collection: “Museum of Living Art” (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1954), p. 5. Like Whitney, Dreier, and Arensberg, Gallatin was an American patron passionate about building a significant collection of modern art in the United States. He conceived his museum as an educational and experimental laboratory in which the public could view—free, and on a daily basis—major works by such artists as Jean Arp, Georges Braque, Klee, Piet Mondrian, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, and many others.7See Gail Stavitsky, “A. E. Gallatin’s Gallery and Museum of Living Art (1927–1943),” American Art 7, no. 2 (Spring 1993):47. In 1942, after losing his display space at New York University, Gallatin donated most of his collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The museum received the collection on a loan basis in 1943 and then definitively in 1952, contributing considerably to its importance as an institution conveying the history of modern art to audiences in the United States.

Gallatin was known for building his collection without professional advisors, instead talking to artists and critics and relying on his own intuition. By the early 1930s he was amassing a large group of Constructivist and Neo-Plasticist works. He liked to acquire art while traveling in Europe, often advised by the French artist Jean Hélion—a friend of Torres-García’s—and in 1932 he made a visit to Torres-García’s Paris studio. Shortly after his visit Gallatin purchased Composition (1929), Street (1930), Head (1930), and Construction (1931). All but Street were included in the 1937 and 1940 exhibitions of Gallatin’s collection at the Gallery of Living Art. A year later, writing about Gallatin’s collection, Hélion described Torres-García as an artist who created “an alphabet of natural forms” (fishes, boats, doors, etc.) and masterfully incorporated those “hieroglyphics” into his “checkerboard” paintings.8Jean Hélion, “The Evolution of Abstract Art as Shown in the Museum of Living Art,” October 1933, in A. E. Gallatin Collection: “Museum of Living Art,” p. 18.

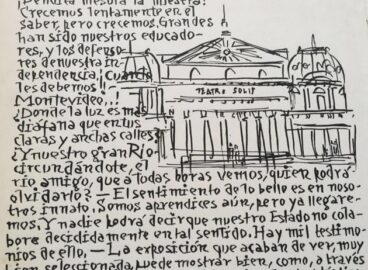

Torres-García and Gallatin corresponded from 1932 until at least 1936, when the artist was living in Montevideo.9See photocopies of letters from Torres-García to A. E. Gallatin, 1932–36, Paris, accession no. 960087, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. In a letter of October 1, 1934, he called life in Montevideo “une belle vie,” and mentioned that he was laboring strenuously to develop not only his own work but also a large school of art with a new orientation.10Torres-García, letter to Gallatin, October 1, 1934, Montevideo. Photocopy, accession no. 960087, Getty Research Institute. Upon arriving in Montevideo, Torres-García had thrust himself into mentoring a younger generation of Uruguayan artists through the formation, first, of the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (1935–39), which delved into pre-Columbian art and aimed to incorporate it into a geometric abstract language, and later the Taller Torres-García (1943–62), which encouraged experimental exercises in all media that would contribute to the creation of a new universal language based on art from past civilizations. The Taller Torres-García fostered many significant artists in Uruguay, among them Torres-García’s two sons, Horacio Torres and Augusto Torres, as well as Julio Alpuy, Gonzalo Fonseca, José Gurvich, and Francisco Matto.11On the Taller Torres-García see Cecilia de Torres and Mari Carmen Ramírez, eds., El Taller Torres-García: The School of the South and Its Legacy, exh. cat. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992).

While Torres-García was living in Montevideo in the 1940s, his work appeared in significant New York venues, and would continue to do so increasingly after his death. In 1942, The Museum of Modern Art acquired two Torres-García works, Composition (1932) and The Port (1942), both of which it included in the 1943 exhibition Latin American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, arranging 200 works to fill all of its second-floor galleries. The exhibition press release asserted that the Museum’s collection of Latin American art was the “most important of its kind in the world.”12“Large Latin American Collection of Museum of Modern Art to be Included in New Exhibition Schedule,” press release, February 16, 1943, available online at www.moma.org/learn/resources/press_archives/1940s/1943/1. The exhibition was on view from March 31 to June 6, 1943. It also listed Lincoln Kirstein, MoMA’s Consultant on Latin American Art, as the exhibition’s advisor. Kirstein’s catalogue essay was the first text in English to attempt a history of the art of South America.13See Lincoln Kirstein, The Latin American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943).

The acquisition of these two works by Torres-García was part of an early-1940s initiative to expand MoMA’s collection of modern and contemporary art by South American artists. Kirstein and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the Museum’s founding director, actively purchased works for the museum’s collection through the newly established Inter-American Fund, which was financially supported by Nelson Rockefeller.14On MoMA’s Inter-American Fund see Miriam Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting and Exhibiting Work by Artists from Latin America,” in Latin American & Caribbean Art: MoMA at El Museo, exh. cat. (New York: Museo del Barrio and The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), pp. 52–68. In an extensive report written in 1943, “Latin American Painting: A Comparative Sketch,” Kirstein identified South American countries he had visited—Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay—and provided biographies of artists and a bibliography of his sources.15Kirstein, “Latin American Painting: A Comparative Sketch,” p. 50, in Lincoln Kirstein Correspondence, series II, “Notes and Reports,” vol. 1, “Latin American Art Notes,” The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. He also identified four painters he had visited in Uruguay the previous year: Juan Manuel Blanes, Pedro Blanes Viale, Pedro Figari, and Torres-García. Of the latter, he wrote:

“While it fell upon Pedro Figari to make his Uruguay known to the rest of the world of modern art, it had been the task of another Montevideano to explain the rest of the world of modern art to the land of his birth. The figure of Joaquín Torres-García is one of the most sympathetic in all Latin America. He is a man whose entire existence has been devoted to painting, who has sought all over the world, the most advanced experimentation, who has taught ceaselessly both by lectures and writing, and who is responsible for some beautiful and original pictures. . . . Yet he is a man of paradox, an Uruguayan who has spent most of his life in Catalonia, an international painter preoccupied with Pre-Columbian forms.”16Ibid., p. 63.

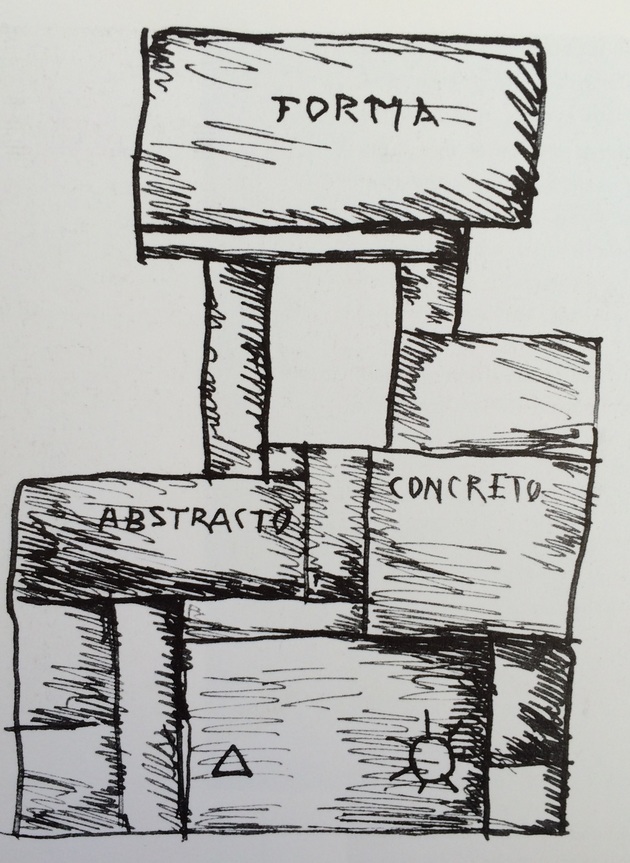

Although reductive, Kirstein’s take is notable in pointing out that Torres-García helped to introduce European art to Montevideo. Indeed, the artist’s Asociación de Arte Constructivo produced an extensive series of lectures, seminars, courses, and a magazine, Círculo y Cuadrado (the Uruguayan counterpart of the short-lived French journal Cercle et Carré, established in Paris in 1929 by Torres-García and Michel Seuphor), all aimed at disseminating the tools of constructivist art and at linking constructivism to pre-Columbian art—a revolutionary approach at the time.

In 1945, René D’Harnoncourt, then the Vice President of Foreign Activities at MoMA, visited Torres-García’s studio in Montevideo during a tour of South America. The visit was described by D’Harnoncourt’s guide, Giselda Zani, in an article in Removedor, a magazine published by the Taller Torres-García.17See Giselda Zani, “Noticia de la visita del Sr. D’Harnoncourt por su acompañante Srta. G. Zani,” Removedor no. 2 (February 1945):3. Founded in 1945, Removedor was published under that name until 1951, when it was renamed Escuela del Sur (School of the South). The artist himself unfortunately missed D’Harnoncourt’s visit owing to fragile health, but his two sons, Horacio and Augusto, were present. According to Zani, D’Harnoncourt had a “profound and extreme reaction” to Torres-García’s work.18Ibid. He left with the gift of the artist’s book Universalismo constructivo (Constructive universalism, 1944), a collection of the 150 lectures Torres-García gave in Uruguay between 1934 and 1943—at over 1,000 pages, an encyclopedic testimony to his fundamental artistic principles.19Torres-García, Universalismo constructivo (Buenos Aires: Poseidón, 1944). The following year, Torres-García wrote to thank D’Harnoncourt for the visit and to inform him of the newly published book Nueva escuela del arte de Uruguay (New school of art in Uruguay, 1946), which shows some of the works he had seen at the studio, as well as some by students at the Taller Torres-García.20Torres-García, letter to René D’Harnoncourt, Montevideo, July 11, 1946, C-46-14, Archivo Museo Torres García, Montevideo. See also Torres-García, Nueva escuela de arte del Uruguay: Pintura y arte constructivo. Contribución al arte de las tres Américas (Montevideo: Asociación de Arte Constructivo, 1946). He was donating a copy of the book to the Museum’s library as part of an ongoing book exchange—indeed he thanked the Museum for sending him two publications, Indian Art of the United States (1941) and Arts of the South Seas (1946).21Frederic H. Douglas and D’Harnoncourt, Indian Art of the United States, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1941), and Ralph Linton, Paul S. Wingert, and d’Harnoncourt, Arts of the South Seas, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946). The contents of these books were surely relevant to his own desire to create a new type of visual language incorporating a universal, symbolic, and spiritual philosophy.

When Torres-García died, on August 8, 1949, he was preparing for two exhibitions in the United States the following year: Torres-García and His Workshop, at the Pan-American Union (now the Organization of American States) in Washington, D.C., and a solo exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery, New York. The Pan-American Union exhibition, with nearly forty works, was the first North American show for Torres-García and his Taller students.22See Torres-García and His Workshop, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: Pan American Union, 1950). Its organizer, the Cuban art critic José Gómez-Sicre, had been part of the Pan-American Union’s Visual Arts Unit since 1946 and was among those working to give South American artists exposure to audiences in the United States through lectures, publications, and exhibitions.23See Stephanie Merry, “Art Museum of the Americas opens ‘Constellations,’” The Washington Post, June 21, 2012, available online at www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/art-museum-of-the-americas-opens-constellations/2012/06/21/gJQACMxBvV_story.html (accessed July 17, 2015). He had served as an advisor to Barr for the Modern Cuban Painters exhibition at MoMA in 1944, traveled extensively to secure acquisitions for North American museums, and had the freedom to organize exhibitions and promote rising artists. In 1961 he would organize a solo show of Torres-García at the Pan-American Union, Joaquín Torres-García of Uruguay.

Torres-García himself chose the works for the Janis Gallery show, which later traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Ranging from 1931 to 1943, most of those he selected were in his constructivist style and resembled “mosaics made up of little compartments in which are found various astrological, commercial, architectural, anatomical and religious symbols . . . juxtaposed to demonstrate an idea or scene.”24[Thomas B. Hess], “Reviews and Previews: Joaquín Torres-García,” Artnews 49, no. 2 (April 1950):45. The structural format of the grid, a matrix Torres-García conceived while in New York almost thirty years earlier, frames his symbols in vertical and horizontal lines within an architectural format to create a unified composition of line, structure, color, geometry, signs, texture, and an intrinsic sense of universality derived from his in-depth study of past civilizations. Sidney Janis later said that the Abstract Expressionist painter Barnett Newman, a constant visitor to the gallery, had shown an interest in Torres-García’s work: “Barney would come almost every day and read the paintings to us. He would go into mythology, history, and everything else—they were pictographs.”25Sidney Janis, quoted in Les Levine, “A Portrait of Sidney Janis on the Occasion of His 25th Anniversary as an Art Dealer,” Arts Magazine 48, no. 2 (November 1973):51. A similar impulse has driven the art historians Werner Haftmann and Irving Sandler to link artists such as Klee and Adolph Gottlieb to Torres-García; those artists’ works too combined mythic signs, abstraction, and grid compositions.26See Werner Haftmann, Painting in the Twentieth Century (New York: Praeger, 1965); and Irving Sandler, The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (New York: Praeger, 1970).

Torres-García’s art, spanning from the late nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century, encompasses an impressive trajectory. His temporary stay in New York in 1920–22 gave him a firsthand experience of American modernism and a chance to meet key members of the American avant-garde. Although his stay in the city had its difficulties, he was able to produce a significant amount of work there and to generate ideas that he would carry over to the latter part of his career. Out of the many cities that he visited during his travels, his time in “the grand metropolis of the United States” would remain for him a time when, along with his fellow Americans, he lived to the rhythm of the city.27Torres-García, New York. Impresiones de un artista, p. 167.

This is the second section of the essay. Read Part 1 here. Excerpted from Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães’ essay “Spirit of America: Joaquín Torres-García in New York, 1920-1922” in the exhibition catalog Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern available at the MoMA Design Store.

- 1Torres-García, J. Torres-García: New York, pp. 74–75.

- 2Tomás Llorens, ed., Torres-García a les seves cruïlles (Catalonia: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 2011), p. 188. See also Cecilia de Torres and Susanna V. Temkin, “New York: 1920–22” and “Italy: 1922–24,” in “Chronology,” Joaquín Torres-García Catalogue Raisonné, available online at http://torresgarcia.com/chronology/ (accessed July 9, 2015).

- 3Llorens, ed., Torres-García a les seves cruïlles, p. 188.

- 4See Torres-García, J. Torres-García: New York; pp. 69–70, 82–83, 103–4, 109, 111–12, 137, 145,147.

- 5Ibid., p. 228

- 6A. E. Gallatin, “The Plan of the Museum of Living Art,” January 1940, in A. E. Gallatin Collection: “Museum of Living Art” (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1954), p. 5.

- 7See Gail Stavitsky, “A. E. Gallatin’s Gallery and Museum of Living Art (1927–1943),” American Art 7, no. 2 (Spring 1993):47.

- 8Jean Hélion, “The Evolution of Abstract Art as Shown in the Museum of Living Art,” October 1933, in A. E. Gallatin Collection: “Museum of Living Art,” p. 18.

- 9See photocopies of letters from Torres-García to A. E. Gallatin, 1932–36, Paris, accession no. 960087, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

- 10Torres-García, letter to Gallatin, October 1, 1934, Montevideo. Photocopy, accession no. 960087, Getty Research Institute.

- 11On the Taller Torres-García see Cecilia de Torres and Mari Carmen Ramírez, eds., El Taller Torres-García: The School of the South and Its Legacy, exh. cat. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992).

- 12“Large Latin American Collection of Museum of Modern Art to be Included in New Exhibition Schedule,” press release, February 16, 1943, available online at www.moma.org/learn/resources/press_archives/1940s/1943/1. The exhibition was on view from March 31 to June 6, 1943.

- 13See Lincoln Kirstein, The Latin American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943).

- 14On MoMA’s Inter-American Fund see Miriam Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting and Exhibiting Work by Artists from Latin America,” in Latin American & Caribbean Art: MoMA at El Museo, exh. cat. (New York: Museo del Barrio and The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), pp. 52–68.

- 15Kirstein, “Latin American Painting: A Comparative Sketch,” p. 50, in Lincoln Kirstein Correspondence, series II, “Notes and Reports,” vol. 1, “Latin American Art Notes,” The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 16Ibid., p. 63.

- 17See Giselda Zani, “Noticia de la visita del Sr. D’Harnoncourt por su acompañante Srta. G. Zani,” Removedor no. 2 (February 1945):3. Founded in 1945, Removedor was published under that name until 1951, when it was renamed Escuela del Sur (School of the South).

- 18Ibid.

- 19Torres-García, Universalismo constructivo (Buenos Aires: Poseidón, 1944).

- 20Torres-García, letter to René D’Harnoncourt, Montevideo, July 11, 1946, C-46-14, Archivo Museo Torres García, Montevideo. See also Torres-García, Nueva escuela de arte del Uruguay: Pintura y arte constructivo. Contribución al arte de las tres Américas (Montevideo: Asociación de Arte Constructivo, 1946).

- 21Frederic H. Douglas and D’Harnoncourt, Indian Art of the United States, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1941), and Ralph Linton, Paul S. Wingert, and d’Harnoncourt, Arts of the South Seas, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1946).

- 22See Torres-García and His Workshop, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: Pan American Union, 1950).

- 23See Stephanie Merry, “Art Museum of the Americas opens ‘Constellations,’” The Washington Post, June 21, 2012, available online at www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/art-museum-of-the-americas-opens-constellations/2012/06/21/gJQACMxBvV_story.html (accessed July 17, 2015).

- 24[Thomas B. Hess], “Reviews and Previews: Joaquín Torres-García,” Artnews 49, no. 2 (April 1950):45.

- 25Sidney Janis, quoted in Les Levine, “A Portrait of Sidney Janis on the Occasion of His 25th Anniversary as an Art Dealer,” Arts Magazine 48, no. 2 (November 1973):51.

- 26See Werner Haftmann, Painting in the Twentieth Century (New York: Praeger, 1965); and Irving Sandler, The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism (New York: Praeger, 1970).

- 27Torres-García, New York. Impresiones de un artista, p. 167.