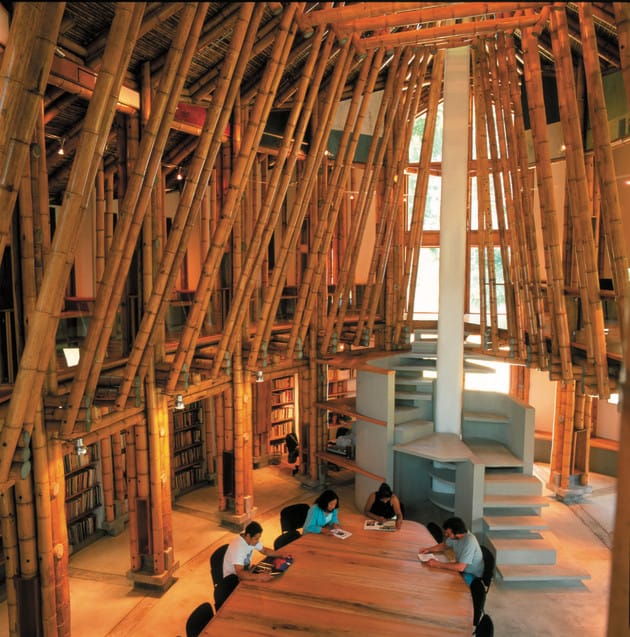

In this interview, Catalina Acosta-Carrizosa, independent curator and former Research Assistant at the Museum of Modern Art, speaks with artist and architect Simón Hosie, the youngest architect to ever be awarded the highest prize at the Colombian Architecture Biennial in 2004. They discuss the interrelation between art and architecture in different fields, the influence of architecture on his own artistic practice, and the importance of working with absolute freedom, in the margins of the art world in Colombia.

Catalina Acosta-Carrizosa: Simón, you are an architect, but you are also an artist. Can you tell us a bit about how those two practices co-exist? How do you go from one to the other? How do they complement each other, or serve different purposes, or fill gaps that you find in one or the other?

Simón Hosie: Yes—the two practices are deeply interrelated, but each offers a unique atmosphere, the chance to explore things I can’t explore through the other.

For me, art is absolutely necessary. I arrive at expressions I can’t approach other ways. This has happened many times, especially in my work tackling different challenges in different parts of Colombia. I suddenly discover I need to tackle an issue that falls beyond the scope of architecture. The chance to study different components, to study individual aspects and then express them, has unexpectedly opened up new dimensions in my work as an architect.

In the same way, many of my architectural processes end up being connected by chance, or as the result of operations I’m initially unaware of, to responses or concerns I approach through art. It is a complex, but absolutely essential, question. It is a continual aspect of my work.

I find it very strange that the co-existence of these practices is often so hard to understand or accept within formal academic spaces, in the disciplines of both architecture and art. Looking at it from only the world of art, or only the world of architecture, it can be hard to see the connections. One must not only understand the discipline in its specificity, but also be able to find points of contact and shared (or found) languages that prove relevant and necessary. This has been, I’d say, the most interesting, most rewarding, and most difficult process. It’s felt like a prison sentence at times, but it has also given me the freedom to find new possibilities outside where I thought they could be.

CAA: This has to do also with the fact that your artistic practice takes place outside of the mainstream of the art world in Colombia. I imagine this gives you flexibility, freedom—You do not depend on a gallery, or on dealers or collectors, correct? Can you speak about how your practice is affected by the absence of those constraints?

SH: It is a feeling I’ve had since I was a child. My father is a painter, and our house didn’t have a living room—it had a painting room. And the painting room was for painting. Watching my father there, I understood that being an artist is being in front of your art, being in that process.

Later, I ran into problems; the kind of confrontations with the art world you have when you’re an artist but don’t want to be part of that world. Since I was very young, I understood that being an artist and being part of the art world were two things that didn’t necessarily go hand in hand. I once read an interview with Julio Cortázar in which he says that every writer needs to find his own language, and that the search can take a long time. He says he watched his friends publish their work right away, while he’d needed to wrap endless books in bookstores and work endless side jobs before finally being able to produce his oeuvre. That made me feel better, gave me a sense of peace. I said to myself, “all right, I want to be an artist, and I want to participate in that world and the language that goes with it, but I don’t need to attach myself right away to the gallery scene or any of that.”

This helped me in my decision to study architecture. Since then, my goal has been to develop a body of work without rules, with absolute creative freedom. It has allowed me to explore different issues through my process, in my studio, and it’s interesting that this work has come to spark interest beyond its immediate context. What began as projects and processes tied to the local, emerging from specific communities, has become something that generates new relations and frictions, when viewed from outside. For me, these outside perspectives enrich the processes I’ve employed for a while now. This is truly gratifying for me, both artistically and personally.

CAA: When you are developing your architectural projects, you spend a lot of time with communities, you live with them, you learn from them, and you talk a lot with them, right? So your practice incorporates ethnographic methodology, and part of that is storytelling. The project Revista Buenas came out of the stories you heard. Can you tell us a bit more about Revista Buenas?

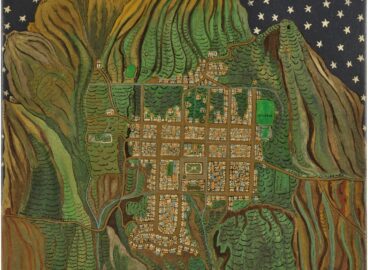

SH: I sometimes find myself in situations that move me, that challenge me and wake me up. Situations that stir feelings of love, friction, frustration, and fear in me, like the one I encountered in Ciudad Bolívar, Bogotá. I feel a need to say something about all that, to narrate it, even though I know I’ll never be able to articulate it the way I’d like to, or at least how I experience it firsthand.

With processes like the one I employed in Revista Buenas and Carta de la lavandera, then, what I’m trying to do is communicate something beyond reason, beyond representation or description along disciplinary lines: I want the viewer to be able to connect through feeling—and that means delving into elements that fall outside logic and reason.

I think each viewer interprets and experiences all this in their own way. In the process of chronicling the extraordinarily individual and solitary lives of the people who live in Ciudad Bolívar, I realized that it is impossible to think about their situation without taking its opposite into account. Because marginality requires its opposite. Thinking about this, I realized that frivolous magazines like Hola! have co-opted the notion of “good taste” and promote their style as such. Not only that, they’ve adopted this peculiar grammar, always using the first-person plural: we know, we were, we visited… It’s a form of collectivizing taste that, obviously, creates an elite that clashes intensely with the far more individual “I” of people who live in marginal neighborhoods like Ciudad Bolívar.

It occurred to me that this clash could serve as a platform, beyond the purely visual, though the visual is essential to a piece like Buenas. For example, the manipulation of the image implied by the use of Photoshop—which at once beautifies and hides, conceals, and denies—takes on entirely new dimensions in my work. All the other situations generated by this clash, from the way language is used to the possibility of an encounter between these two worlds seemed like really interesting questions worth exploring.

CAA: I have one last question. Since your practice is generally situated on the margins, because you wanted it that way (you work in marginal cities, your artistic practice operates outside the boundaries of the mainstream…), would it make any sense to show your work in a museum like MoMA? Do you think we can either dislocate the work from its original context or recontextualize it in a place like this museum?

SH: Well, that’s not entirely my concern. It’s more the concern of the curators I’ve been dealing with recently, when I’m invited to speak in spaces like this one. Curators and art historians often ask me how my work fits in within the museum, how it could be shown in a place like MoMA. I didn’t develop my body of work to show it in MoMA, I’ve never made a piece to be shown in a gallery. The idea that the public might discover or come to face with things I’ve tried to express will always be an exciting one for me. I hope it happens, and that it happens in many ways, or, as they say, in lots of ways. But all that falls outside the scope of what I’m doing. That part involves the ability, the capacity of other people; speaking with those people, possibilities I hadn’t considered open up. As an artist, I always hope to see my work completed through its public viewing. I’ve never forced a piece to make it fit a given space, but I have seized opportune moments and situations to show them. From that moment on, the work is mutable, dynamic. It can be seen in different ways. And that’s the most interesting part, isn’t it?