A patient carrying his amputated leg; heads applied to different bodies; important historical figures excised by photo technicians during dictatorial rule… Located in Shkodra, Albania, The Marubi museum contains a collection of more than five hundred thousand negatives dating from the second half of the nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth. Derived from its namesake, the Marubi photography studio founded in 1858, the museum features a multifaceted view of the uses–artistic, social, cultural, and political–of the photographic medium over the course of a century and a half in Albania.

The Albanian version is available here.

The history of photography in Albania begins with the Italian photographer Pietro Marubbi (1834–1903), who settled in the city of Shkodra during the second half of the nineteenth century and opened the first photography studio there in 1858. The Marubi, the National Photography Museum and Albania’s first photography museum, opened in May 2016. The core of its collection is comprised of what was formerly the contents of the Marubi Photothèque.

Having no children of his own, Pietro Marubbi’s first assistants and faithful successors in the field of photography were Mati and Kel Kodheli, the sons of his gardener Rrok Kodheli. Pietro sent Mati, the older of the two brothers, to Italy to study photography at the Sebastianutti & Benque studio in Trieste. When Mati died prematurely at age nineteen, in 1881, Pietro adopted Kel, whom he also sent to Italy to study and who would later assume the surname Marubi. Upon Pietro’s death in 1903, Kel inherited his adopted father’s studio and continued its work. He, in turn, was followed into business by his own son, Gegë Marubi, who studied photography and cinematography in France at the Lumière brothers’ studio. What is notable through three generations of photographers is the desire to be modern, and as such, to stay abreast of contemporary aesthetic trends and new technologies.

With the onset of Communist rule in the 1940s, when every private enterprise was prohibited by law and he was unable to independently use and/or promote his own work or that of his ancestors, Gegë Marubi was forced to turn over his family’s archive to the state. This way, although unable to remain in private business, he could oversee the Marubi archive. Other photo studios that had opened in Albania over the course of the same decades, including Dritëshkroja e Kolës (1886), Fotografija Pici (1924), Foto Jakova (1932), and Foto Rraboshta (1943), also had to relinquish their images. From these combined sources, the Marubi Photothèque was founded as a division of the Historical Museum of Shkodra. It remained a part of this museum until 2003, when it became an autonomous institution.

The Marubi museum preserves and promotes this collection of more than five hundred thousand negatives dating from the second half of the nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth. The Marubi family archive, along with archives of many other photographers in the museum’s holdings, document pivotal moments in Albanian social, cultural, and political life over the course of a century and a half.

Manipulation

The invention of photography through the process of heliography opened the door to further development of the medium, including the manipulation of images1Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present, rev. ed. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 15–16. Direct intervention in print, including retouching or scratching; use of artificial lighting; and the manipulation of negatives has played a significant role in how an image is viewed. Historically, images have been altered to deceive, impress, or distort so-called truth, or to create false idols.

In 2013, when the entire Marubi archive was re-inventoried, previously unknown negatives were discovered. This process took place about forty years after Gegë, the last member of the Marubi Dynasty, undertook an inventory of the entire archive. These newfound images are testaments to an early history of photographic manipulation in Albania, beginning in the late 1800s. Among them is a photomontage created in 1860 by Pietro Marubbi (fig. 1), in which its subject Giacinto Simini is depicted in three different roles—that of a client who, clothed in the traditional Catholic dress of Shkodra, leans against a miniature building resembling a hospital; that of a patient carrying his own amputated leg; and that of a surgeon holding a hatchet. In trying to piece together a logical narrative to explain the combination, one should know that Giacinto Simini was the son of the Italian doctor Gennaro Simini, an immigrant in Ottoman Albania who, like many other Italians, had left Italy in the nineteenth century because of political persecution during the Risorgimento. Giacinto’s book, Un patriota leccese nell’Albania ottomana (2011), is certainly foreshadowed in this image, which served as an advertisement for the hospital his father had opened in Shkodra.

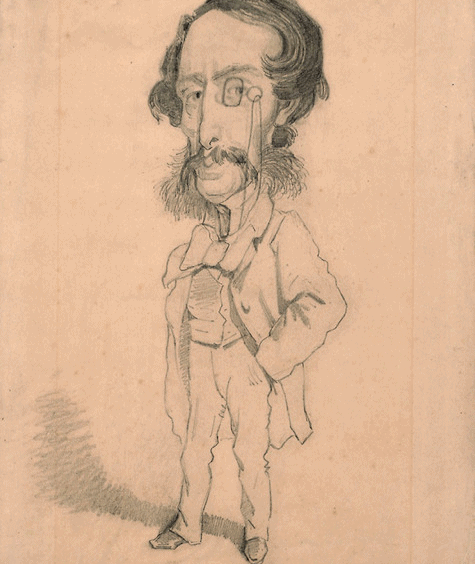

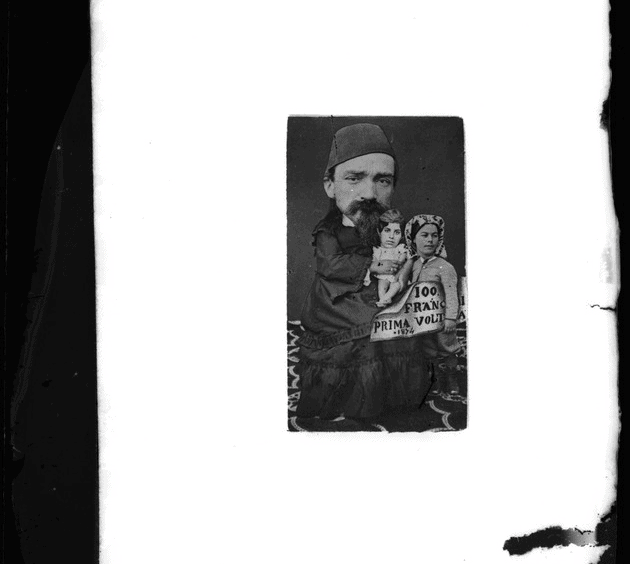

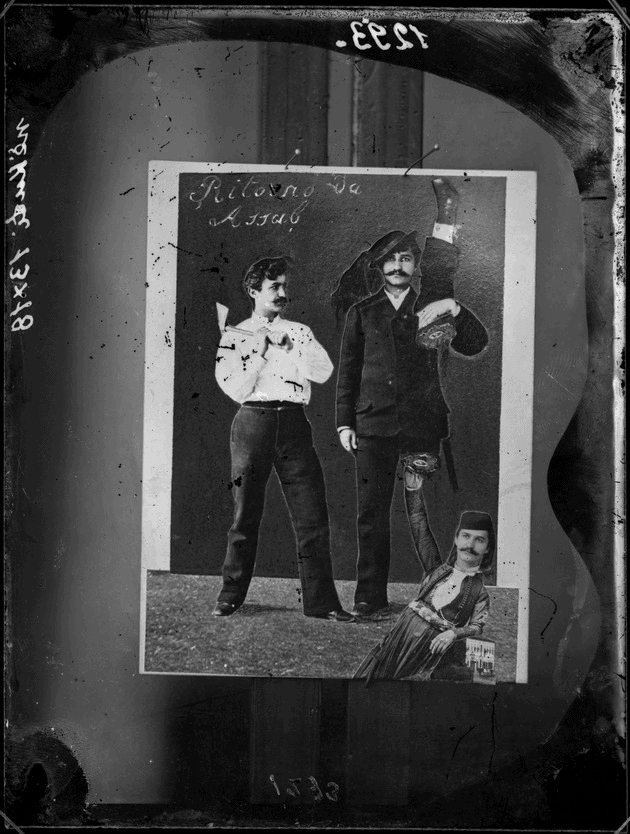

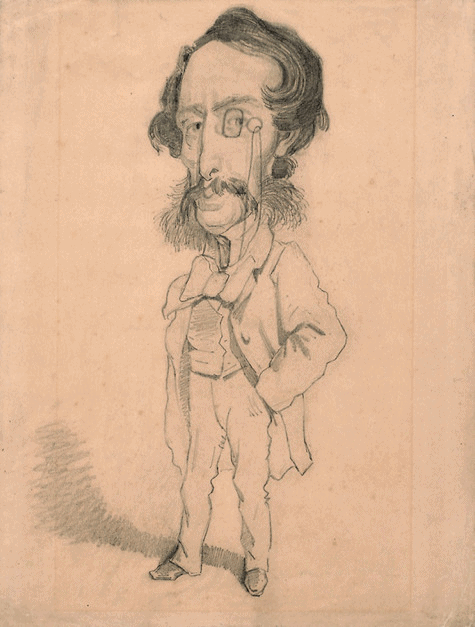

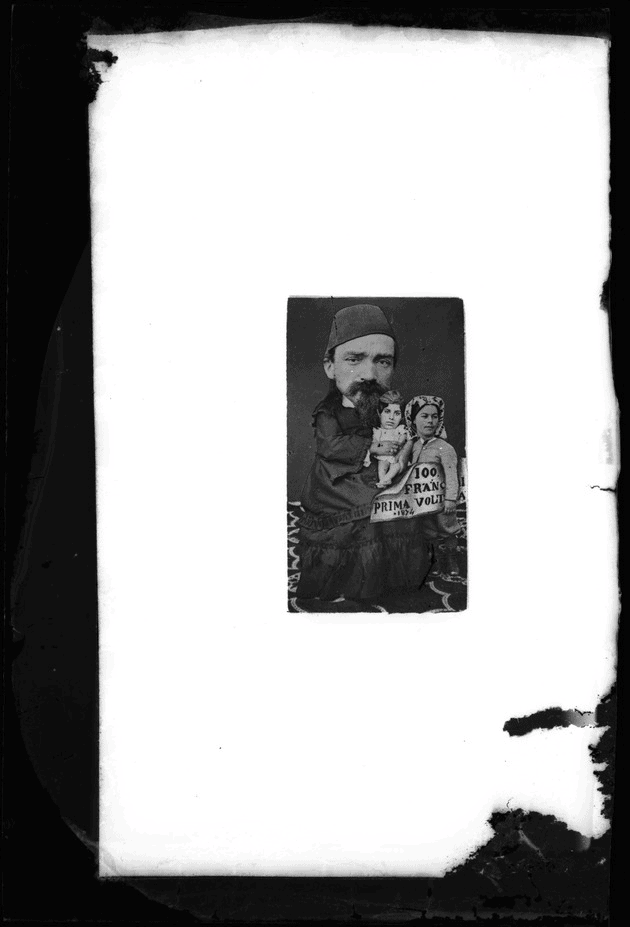

Another early shot uses the wet-plate collodion process (fig. 2) to depict Pietro Marubbi, whose “big” head is mounted on a body too small for it, the composite applied to the side of an oversize coffee cup sitting on what looks to be a wooden cupboard. Curiously reminiscent of caricatures made by the Impressionist painter Claude Monet in the 1850s, this image was likely shot between 1865 and 1875, when there was mass dissemination of European caricatures. The archive holds many other such experimental images, including Visto buono per Napoli (fig. 3) and 100 franchi prima volta 1874 (fig. 4), both of which are photomontages by Pietro Marubi; a double portrait of Kel Marubi and his sister, whose heads have been mounted on the bodies of two African fighters (fig. 5); and a portrait of Jak Bjanku with his friend, each of whom holds up an image of the other’s head (fig. 6).

Following in Pietro’s footsteps, Kel and Gegë Marubi continued to develop photographic manipulation techniques. Like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s image in which he poses as an artist and model (1892), Gegë appears in a double portrait—as himself and as an interlocutor (fig. 7). Further examples reflecting the use of new techniques by the next generations of Marubis are images from 1927 (fig. 8) and 1940 (fig. 9). In both, the priest Anton Kiri is captured asleep—in a chair in the earlier picture and on a branch in the later one—while a “ghost” plays the violin alongside him.

Not all of the manipulated photographs in the Marubi family archive are experimental, however. For example, certain images were altered using ink and other means to eliminate “enemies of the state.” This was a common Communist practice that spread quickly throughout the Eastern bloc countries, including in Albania. In 1952, the Albanian authorities set up state-run photography departments, initially as part of the “Cooperative for Repair Services.” Employees of these departments became photographers and lab technicians, as well as members of the state security overseeing the process of censoring and/or “repairing,” i.e., manipulating, images. Photographers who had previously worked in their private studios were not only forced to hand over their archives—but also to work for the state in this capacity. Some of the Marubi family’s photographs that were confiscated in this process were then altered for use as political propaganda.

During the dictatorship period in Albania, records were created based on the limited information the Marubi family was allowed to provide. The errors photographers made when registering their original photographs, and the additional mistakes made when data from old inventories was transcribed to new ones, were the cause of misinformation and historical deviations.

The first publication of the Marubi Dyansty’s photographs, Traces of the National History in the Phototheque of Shkodra (1982), includes a series of manipulated images from which Albanian patriots have been erased or cut. For example, a well-known photograph by Kel Marubi from 1923 depicts the deputies of Shkodra with Luigj Gurakuqi, secretary of the Independence Government; the priest Dom Ndre Mjeda; and Father Gjergj Fishta, a national poet (fig. 10). These men significantly influenced Albanian political and cultural life, their impact shifting the course of the political events that followed in 1921–24, but during the Communist regime in Albania, the only version of the photograph allowed to circulate was the one in which Father Gjergj Fishta had been erased. This was due to the fact that his Christian, national, and anti-chauvinist views conflicted with Communist ideology (fig. 11).

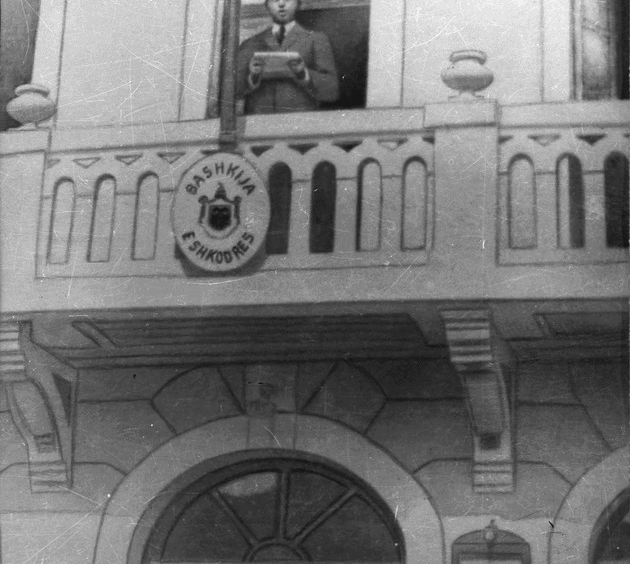

The album also includes one of the most spectacular photographs of the Communist regime’s manipulation period, in which all but one of the people standing on the balcony of the building of the Municipality of Shkodra for the reburial of the patriots Çerçiz Topulli and Mustafa Qulli in 1936 (fig. 12) have been erased. In the manipulated version of the photograph, originally taken on September 12, 1936, the only person shown is the dictator Enver Hoxha, who is delivering a speech (fig. 13).2“Nderimi i Shkodrës eshtnave të dy deshmorëve Çerçiz Topullit e Mustafa Qullit,” Revista “Cirka”, no. 9 (Shkodër, September 27, 1936):141.

What is the hidden story behind this retouched photograph? One of the reburied patriots was from Gjirokastra (Ç.Topulli), the other from Leskovik (M. Qulli). In honor of the occasion, the mayor of Shkodra, Javer Rushidi had invited local authorities to make speeches and delegations from Gjirokastra and Leskoviku to honor the patriots. Enver Hoxha, who at that time was only twenty-eight, had just returned from Belgium, where he worked for the Albanian consulate, and gave a speech as a representative of Gjirokastra’s youth.3Dervishi, Kastriot, “Fotografia në sallën e Bashkisë së Shkodrës në vitin 1936, E. Hoxha heq gjysmën e pjesëmarrësve,” Gazeta 55 (Tiranë 2018). Various hypotheses suggest that he was at that time a part of the King Zogu youth assembly. Once Hoxha was in power, any image or document from his life prior to 1936 disappeared or was altered. Analysis of images in books about his life (1908–1985) published by the Institute of Marxist-Leninist Studies at the Central Committee of the Albanian Working Party indicate that almost everything was manipulated, including this image, which is part of the Marubi archive.

The First Albanian Photography

Numerous untouched negatives found in the archive and research led to a very important and ongoing debate in Albania about the first Albanian photograph, taken by Pietro Marubbi in 1858 of Hamza Kazazi, the Albanian fighter and leader known for his role in Albanian Uprising of 1835 (fig. 14).

Scholar Zija Shkodra argues that Marubbi’s photograph of Kazazi is not the first example of Albanian photography since, in 1858, Kazazi was interned in Istanbul. “This argument is further supported by the face of the subject, that of a 50-year-old man, not a 79-year-old one, which Hamza Kazazi was in 1859.”4Zija Shkodra, “Për fotografinë dhe shkrimin e varrit të Hamza Kazazit, atdhetar i shquar etj” (paper, Muzeu Historik i Shkodrës, Seminari i Tretë Ndërkombëtar “Shkodra në Shekuj,” Vëllimi I, Shkodër, 2000), 97–105 Another scholar, Dashnor Kokonozi, claims that “great photographers of that time avoided taking standing portraits since there is no guarantee of the person’s stature in front of the lens, which surprisingly is not the case with Marubbi. In 1858, he took portraits of people standing.”5Dashnor Kokonozi, “Vërtet kemi një fotografi 151-vjeçare?,” Gazeta Shqip (Tiranë, 2009): 14-15 Although both authors are correct in their analyses, neither was able to give additional explanation regarding this issue for the simple reason that the Marubi archive was not available for research until it began to be digitized in 2013.

What would change if they had been able to conduct additional research? After reading previous publications and partaking in several debates, my interest intensified. Willy Kamsi, former ambassador of the Republic of Albania to the Holy See in the Vatican, told me that the person posing in Marubbi’s first photograph was, in fact, an Italian consul in Shkodra.6Willy Kamsi, in conversation with the author, February, 2012. While that information greatly surprised me, it propelled me to seek the truth.

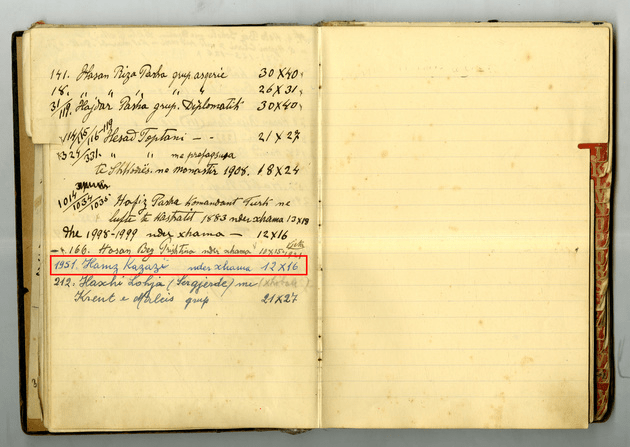

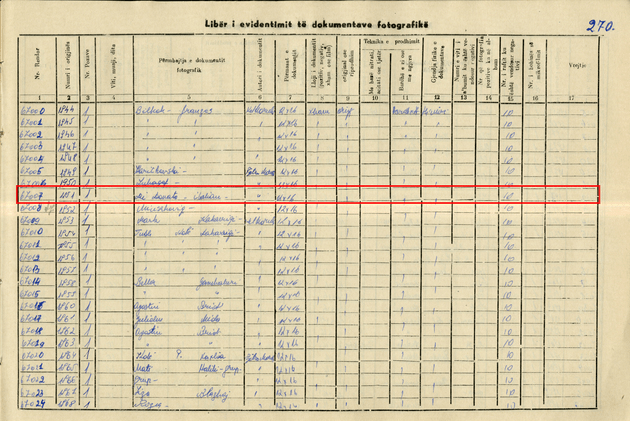

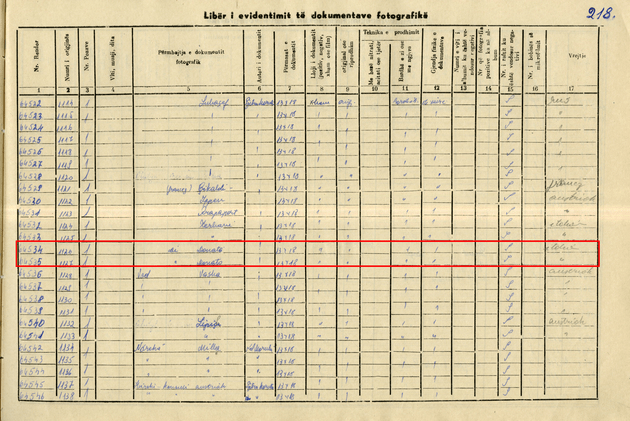

I immediately asked the archive staff to locate all of the photographs of the Italian consuls of Shkodra using the inventory records made in 1972–79 by Gegë Marubi as a guide. Two days later, I received a surprising response. One of my coworkers in the archives had gathered all of the images of the Italian consuls, among them “Hamz Kazazi.”7Hamza Kazazi is also known as Hamz Kazazi. “Hamz” is how Gegë Marubi wrote “Hamza” in the register. Upon reviewing them, I realized that something was not right, and in checking Gegë’s records against earlier ones, noticed that the number and size of the negatives listed were the same, but that the description in the older registry (fig. 15) did not correspond to the newer one (fig. 16).

The older registry, titled “Eminent people and important items” (fig. 15.1), notes: “Hamz Kazazi, Origin number (negative), 1951, 12×16.” Whereas, Gegë’s registry (fig. 17) notes: “Serial number: 67007, Origin number (negative) 1951, the Content of the document: Di Donato, Author of the Document: Pietro Marubbi, File Size: 12×16, Number of the shelf where the negative was placed: Shelf 9.” Analyzing both registries, I noticed that the records for photographs of Hamz Kazazi had been added later to the older of the two—and written in a different ink. Evidently, the earlier registry had been manipulated but we do not know why or by whom.

Further investigation revealed that the person in the photograph is in fact the Italian consul Alessandro De Rege di Donato, who served in Shkodra from February 20, 1881, to February 18, 1886, and not Hamza Kazazi. A relevant discovery was another portrait of di Donato (fig. 18), also found in the archive. By magnifying both faces, I could see that they are one and the same person. These findings confirm that what has been recognized as the first Albanian photograph in publications regarding the history of photography in Albania, has in fact been misrepresented—reopening the discussion about what is, in fact, the first Albanian photograph.

Photographic manipulations undertaken over the course of fifty years by the Communist regime for political and ideological reasons have affected and shaped the history photography and of our country. The ongoing digitization of the Marubi archive is enabling further research and analysis of this practice and its impact. The museum’s collection not only provides historical content but also evidence of the sociocultural context in Albania over the course of a century. With only one-fifth of the archive digitized, the work of the Marubi remains essential to saving the most important photography collection in Albania. Year after year, this process sheds light on new images, offering a new perspective and better understanding of a history that was intentionally manipulated to distort—a precious history that some didn’t know about and still others were not allowed to learn.

*The exhibition Manipulation, which opened in August 2017 at Marubi, the National Photography Museum, shared for the first time these manipulated images spanning the years before and during the Communist regime. The exhibition is also a legacy of the historical and cultural importance of an archive to revealing real facts proven by original negatives that were exhibited for the first time.

Translated from Albanian by Hana Halilaj.

- 1Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present, rev. ed. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 15–16

- 2“Nderimi i Shkodrës eshtnave të dy deshmorëve Çerçiz Topullit e Mustafa Qullit,” Revista “Cirka”, no. 9 (Shkodër, September 27, 1936):141.

- 3Dervishi, Kastriot, “Fotografia në sallën e Bashkisë së Shkodrës në vitin 1936, E. Hoxha heq gjysmën e pjesëmarrësve,” Gazeta 55 (Tiranë 2018).

- 4Zija Shkodra, “Për fotografinë dhe shkrimin e varrit të Hamza Kazazit, atdhetar i shquar etj” (paper, Muzeu Historik i Shkodrës, Seminari i Tretë Ndërkombëtar “Shkodra në Shekuj,” Vëllimi I, Shkodër, 2000), 97–105

- 5Dashnor Kokonozi, “Vërtet kemi një fotografi 151-vjeçare?,” Gazeta Shqip (Tiranë, 2009): 14-15

- 6Willy Kamsi, in conversation with the author, February, 2012.

- 7Hamza Kazazi is also known as Hamz Kazazi. “Hamz” is how Gegë Marubi wrote “Hamza” in the register.