In a sketchbook that dates to her early student years at Framingham State College (now Framingham State University) in the mid-1970s, the artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, 1940–2025) wrote, “[I] have a brainstorm . . . to do a series of paper dolls.”1Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, unpublished sketchbook, c. 1975, shared with author, October 5, 2021.This annotation shares the page with two drawings: a paper figure with a folded base and the tabbed outfit with which it could be paired. The clothing ensemble includes a crisply starched dress layered underneath an apron embellished with a heart-shaped appliqué spelling “Mom.” Alongside the two drawings, Smith penciled a block of ruled lines as if from a composition book and neatly printed “American Public School Education Series.”

Smith recognized dolls to be powerful pedagogical tools that could shape aspirations, perpetuate stereotypes, and ascribe or reinforce societal roles.2One example of this is a work on paper that Smith created in 1992 titled I See Red: Ten Little Indians. This drawing depicts doll-like silhouettes against a blackboard and invokes the once ubiquitous nursery rhyme used to teach children numbers. Different versions of the song have existed since the late nineteenth century, most adhering to a formula that counts down from ten to zero as “little Indians” are either shot, drowned, or disappeared. Veiled as a lesson in counting, the primary instructional message is one of violence as well as perpetuating the myth that Native Americans no longer exist.Below the apron-strung mother in her sketch, Smith dotted the edge of the page with words including “doctor,” “detective,” and “lawyer.” These read like a laundry list of professions that most young girls of her generation were discouraged from pursuing. Born in 1940, Smith was herself a parent while completing her postsecondary training in fine art. Well-meaning and condescending instructors alike implored her to consider becoming an art teacher, reasoning it was a more suitable and rewarding line of work for a Native American woman.3For more on Smith’s recollections of the challenges she faced during her education, see Lowery Stokes Sims, “A Conversation with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,” in Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, by Laura Phipps, exh. cat. (Yale University Press in association with Whitney Museum of American Art, 2023), 15–21; and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Oral History Interview with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,” interview by Rebecca Trautmann, August 24 and 25, 2021, transcript, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/download_pdf_transcript/ajax?record_id=edanmdm-AAADCD_oh_22089.

Smith didn’t create the first of the paper dolls until the early nineties, but she never abandoned the idea in those intervening years. Some of her earliest doll works were in fact sculptures, from raggedy cloth moppets to wire figurines. In Tribal Ties (1985), two lovingly hand-stitched and pillowy dolls with button eyes embrace one another.4Smith made approximately thirty of these dolls. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, unpublished transcript of a conversation with the oral historian Jane Katz, July 14, 1990, shared with author, October 11, 2021. At least one pair was exhibited in The Doll Show: Artists’ Dolls and Figurines, Hillwood Art Gallery, Long Island University, December 11, 1985–January 29, 1986. Later, Smith made use of store-bought toys. The Red Dirt Box (1989) is wooden and pocket-size with a plastic Statue of Liberty affixed to the lid. “Give me your tired, your poor” is handwritten on one side.

The “Mother of Exiles” had come to stand for a compassionate center of power, distinct from the conquering empires of yore. In Smith’s sculpture, she is set askew, revealing the contents of the box beneath her: action figures of Plains warriors, who lay flat on their backs, half-buried in the soil. The configuration of the work suggests that righting her would bury them. The scattered plastic bodies of the warriors are solid blue and white. There are no red men, leaving the would-be trio of patriotic colors incomplete. The expression of “red” as a shorthand slur for Native Americans is reappropriated by Smith to present an image of the United States as partial and unfinished without Indigenous peoples. The Red Dirt Box upends the superficial national story of a land for one and all; colonialism is not so easily disguised.

Smith’s artistic games are serious. Her work alludes to childhood pastimes but not for fun (although play and humor are important)—or because her professors thought it would be better for her to work with children than in the field of contemporary art—but rather because early development is when the norms of social and cultural life are established.5Smith’s art, activism, and commitment to education were deeply intertwined aspects of her practice. The artist has said, “My aim is to make a teaching moment from something that I feel we don’t hear in everyday life and don’t learn in school.” See Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony: Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World,” MoMA Magazine, December 20, 2024, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/1162.In an unpublished document from the artist’s archive, Smith imagines a conversation between a katsina figure and a Cabbage Patch doll taking place in her studio in Corrales, New Mexico, over the course of two days in 1985. The transcript, titled “Fad or Fetish,” records the speakers politely bickering over their origins and responsibilities: Who is a more American product? Who has been more commercialized? Eventually, they come to realize their similarities, including a shared disdain for the bourgeois aspirations of Barbie and Ken. They also agree that each has a role to “help make order in our worlds” and to “teach children about love, hate and nurturing.” Whether used in ceremonial and religious rites or for secular purposes, “dolls reassured the human place in the universe by acting out what the human could not do . . . but they also involve fantasizing and dreaming which made their world a better place.”6Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Fad or Fetish,” unpublished document, 1985, shared with author, September 18, 2021.Dolls are instruments that can reproduce social codes, but they are also agents of change.

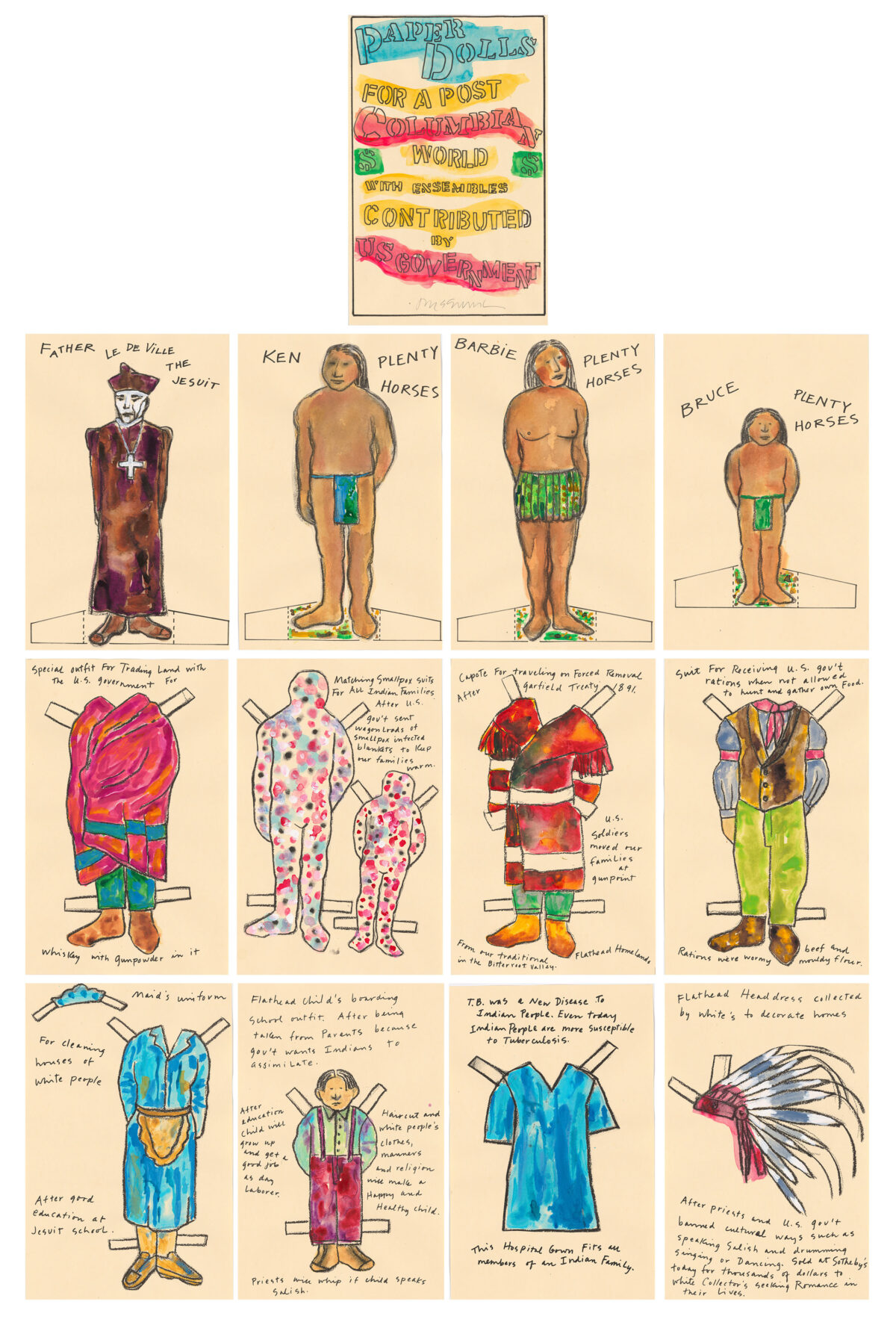

In 1991, Smith created Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government, a suite of 13 xeroxed drawings tinted with watercolor and pencil.

Paper Dolls depicts an imagined family of Barbie, Ken, and young Bruce Plenty Horses, as well as the black-robed Jesuit priest Father Le de Ville––a homonym of “devil.” On the Flathead Reservation, where Smith grew up, the Jesuits operated a Federal Indian Boarding School from 1864 to 1972. This was one of more than 400 schools jointly run by missionaries and the colonial government in the United States. Like those that existed in Canada, these institutions aimed to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into a Christian Euro-American worldview. This was done by separating them from their families, language, culture, and religion. These bitterly hostile places were rampant with abuse, and many children never made it home. Those who did survive were impacted in existential ways that Smith’s artwork carefully records.

Paper Dolls illustrates how boarding schools, land grabs, biological warfare, criminalizing ceremonial practice, and the theft of cultural belongings are interlinking strategies of genocide. As Smith once said, “People think that genocide is just about standing people in front of an open pit and shooting them. . . . They think it’s about murdering people. It’s way bigger than that.”7Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony.”The sheet depicting the outfit for Bruce, the child, is especially demonstrative of this reality. Whereas the hospital gown or the capote or the maid’s uniform are garments alone, the “Flathead child’s boarding school outfit,” as Smith labeled it, comes complete with a figure.

Another boy is already there. His mouth is pressed closed, his hair is cut short, and the color of his skin is noticeably lighter. To wrap Bruce Plenty Horses in this outfit is not to clothe him, but rather to replace him with someone else.

The teacherly style of Smith’s handwritten notations is a direct response to the historical fallacies printed in textbooks and otherwise circulating widely at the time. These were the frenzied years leading up to the Columbian Quincentenary in 1992. Major cultural organizations received grants to develop blockbuster projects and exhibitions, many of which perpetuated a narrative of “encounter and exchange” between Indigenous peoples and European invaders––a perspective that offered a benign and teachable framework of multicultural harmony. To some, this even felt like a progressive step, an update of the older “discover and conquer” model. Students of history would learn that things were bad but that now they’re good, while absolving settler society of wrongdoing. “That’s what 1992 was about,” Smith recalled. “This whole big propaganda machine in America was overwhelming the whole story. Making up a new story. I couldn’t stand it.”8Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony.”Smith’s infuriation catalyzed a few strategic shifts that she began to make at the time.

Paper Dolls is unusual as a drawing in that there are multiple sets.9In addition to the drawingin MoMA’s collection, versions of this work are held in the collections of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis and the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, and one set remains with the artist’s estate.It pushes against the categorical line that separates a drawing from a print. Smith was an expert printmaker, having worked with the renowned Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico, since 1979.10Smith, “Oral History Interview with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.”She could have easily created Paper Dolls as an editioned lithograph, for example, but instead produced the work more like the handbills and fliers that plaster streets and circulate on the ground during times of political activity. Indeed, a reproduction of Smith’s Paper Dolls landed on the cover of How to ’92: Model Actions for a Post-Columbian World.11Kirsten Aaboe, Lisa Maya Knauer, Lucy R. Lippard, Yong Soon Min, and Mark O’Brien, eds., How to ’’92: Model Actions for a Post-Columbian World (Alliance for Cultural Democracy, 1992).This interventionist booklet offers a guide for do-it-yourself actions to counter the misinformation of the quincentenary: how to mount a demonstration, how to initiate media campaigns, and how to petition for curricular revisions. By opting to draw Paper Dolls, Smith may have intentionally created some distance from the master matrix that printmaking relies upon. This artwork underscores the violence of enforcing a singular worldview, and drawing allowed Smith to forego identical impressions for a process more intimately connected to uniqueness and individuality. One drawing was maybe not enough to reach the audience she needed, given what was at stake, but perhaps several versions would be.

In 2021, Smith returned to the idea of paper dolls.

Even though her practice had always been invested in contemporary politics, this was an exceptional moment of prescience. The revisitation of this work coincided with the announcement of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative. The final volume of the investigative report was released in 2024. “For the first time in the history of the United States,” Deb Haaland, Secretary of the Interior, declared, “the federal government is accounting for its role in operating historical Indian boarding schools that forcibly confined and attempted to assimilate Indigenous children.”12US Department of the Interior, “Secretary Haaland Announces Major Milestones for Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative,” press release, July 30, 2024, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-haaland-announces-major-milestones-federal-indian-boarding-school.This comprehensive federal effort outlined recommendations to recognize the legacy of these policies with the goal of addressing intergenerational trauma and providing a path toward healing.

Paper Dolls from 2021 shares its name with the earlier series, but Smith transformed the scale and the material. The installation involves nearly life-size aluminum cutouts of the painted figures and their outfits. Smith designed them so that they come away from the wall, creating a dimension of depth and shadow. The imagery is identical to the earlier work, but the written descriptions are absent. Whereas the paper versions were carriers of explanations and historical facts, the sculptural dolls—which connect to Smith’s earliest approach to doll-making—are physically embodied. It is as if the core of Smith’s lesson to audiences today is one of relationality. The history is important, but so is our position toward it in the present. “My messages are about things that have happened in the past that impact what’s happening today,”13Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony.”she maintained.

Smith was awarded four honorary doctorates over the course of her lifetime and an honorary baccalaureate from Salish Kootenai College, an accredited tribal college founded in 1978 that offers essential services to those in her home community. Smith was a longtime supporter of Salish Kootenai’s library and arts programs. In her speech for the school’s 2015 commencement ceremony she began, “This honorary degree from Salish Kootenai means more to me than all four honorary doctorates from mainstream universities.”14Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, acceptance speech upon receiving an honorary Bachelor of Arts degree in Indian Studies, Salish Kootenai College, June 6, 2015.Encouraging the students seated before her, she continued, “My story is about how a child develops resiliency and coping mechanisms in a difficult and disenfranchised world.”15Smith, acceptance speech.Smith’s relationship to the classroom was one she navigated with criticality and determination. Her role as a teacher was neither vocational nor a consolation to her. She was deliberate in how, when, and where she taught, and her artwork became one of most powerful platforms from which she advocated for education. Smith used dolls throughout her practice in service of that wider strategy, as an unassuming yet powerful motif to redress political and cultural injustices.

In Memory of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1940-2025).

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World 1991 is currently on view in Gallery 208 at MoMA.

- 1Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, unpublished sketchbook, c. 1975, shared with author, October 5, 2021.

- 2One example of this is a work on paper that Smith created in 1992 titled I See Red: Ten Little Indians. This drawing depicts doll-like silhouettes against a blackboard and invokes the once ubiquitous nursery rhyme used to teach children numbers. Different versions of the song have existed since the late nineteenth century, most adhering to a formula that counts down from ten to zero as “little Indians” are either shot, drowned, or disappeared. Veiled as a lesson in counting, the primary instructional message is one of violence as well as perpetuating the myth that Native Americans no longer exist.

- 3For more on Smith’s recollections of the challenges she faced during her education, see Lowery Stokes Sims, “A Conversation with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,” in Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, by Laura Phipps, exh. cat. (Yale University Press in association with Whitney Museum of American Art, 2023), 15–21; and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Oral History Interview with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith,” interview by Rebecca Trautmann, August 24 and 25, 2021, transcript, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, https://www.aaa.si.edu/download_pdf_transcript/ajax?record_id=edanmdm-AAADCD_oh_22089.

- 4Smith made approximately thirty of these dolls. Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, unpublished transcript of a conversation with the oral historian Jane Katz, July 14, 1990, shared with author, October 11, 2021. At least one pair was exhibited in The Doll Show: Artists’ Dolls and Figurines, Hillwood Art Gallery, Long Island University, December 11, 1985–January 29, 1986.

- 5Smith’s art, activism, and commitment to education were deeply intertwined aspects of her practice. The artist has said, “My aim is to make a teaching moment from something that I feel we don’t hear in everyday life and don’t learn in school.” See Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony: Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World,” MoMA Magazine, December 20, 2024, https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/1162.

- 6Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Fad or Fetish,” unpublished document, 1985, shared with author, September 18, 2021.

- 7Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony.”

- 8Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony.”

- 9In addition to the drawingin MoMA’s collection, versions of this work are held in the collections of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis and the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, and one set remains with the artist’s estate.

- 10Smith, “Oral History Interview with Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.”

- 11Kirsten Aaboe, Lisa Maya Knauer, Lucy R. Lippard, Yong Soon Min, and Mark O’Brien, eds., How to ’’92: Model Actions for a Post-Columbian World (Alliance for Cultural Democracy, 1992).

- 12US Department of the Interior, “Secretary Haaland Announces Major Milestones for Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative,” press release, July 30, 2024, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-haaland-announces-major-milestones-federal-indian-boarding-school.

- 13Smith, “Dressing the Truth in Irony.”

- 14Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, acceptance speech upon receiving an honorary Bachelor of Arts degree in Indian Studies, Salish Kootenai College, June 6, 2015.

- 15Smith, acceptance speech.