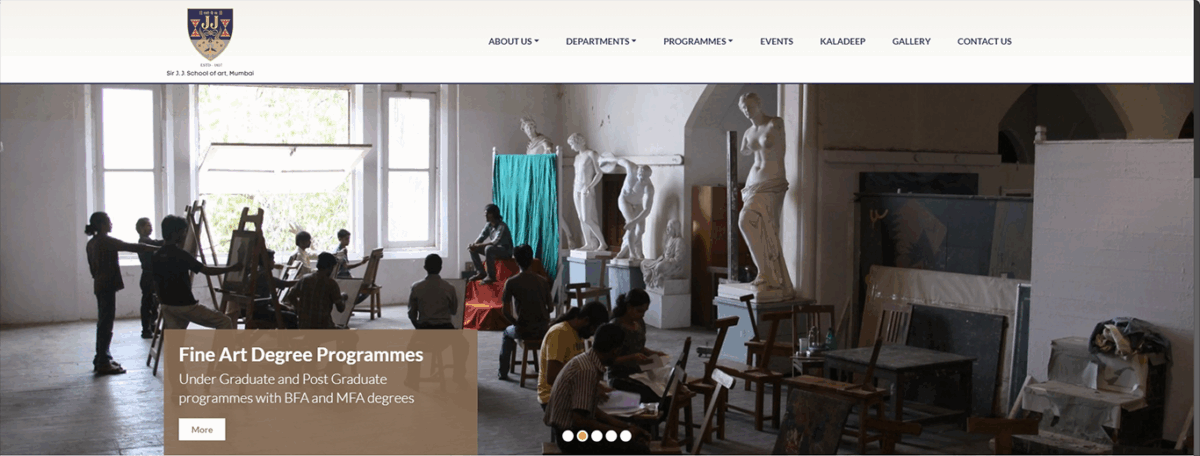

In looking at photographs of live models, plaster casts of Greek sculptures, and students on the website (figs. 1a and 1b) of the Sir J. J. School of Art (JJ) in Bombay (present-day Mumbai), one notices how the condition of the body and labor in relation to art is a haunting presence in 20th-century photography. Shot between the 1930s and 1990s by three notable photographers—Homai Vyarawalla (1913–2012), Foy Nissen (1931–2018), and Raghubir Singh (1942–1999)—the photographs I’ve chosen to highlight in this essay articulate the interface of art and labor over a long and unwieldy terrain.1This study shows how neither the photographs nor the discussions they provoke are bookended spatiotemporally by these decades. I also analyze how these images capture the unstable status of student artists and its correspondence to the precarious trajectory of JJ.

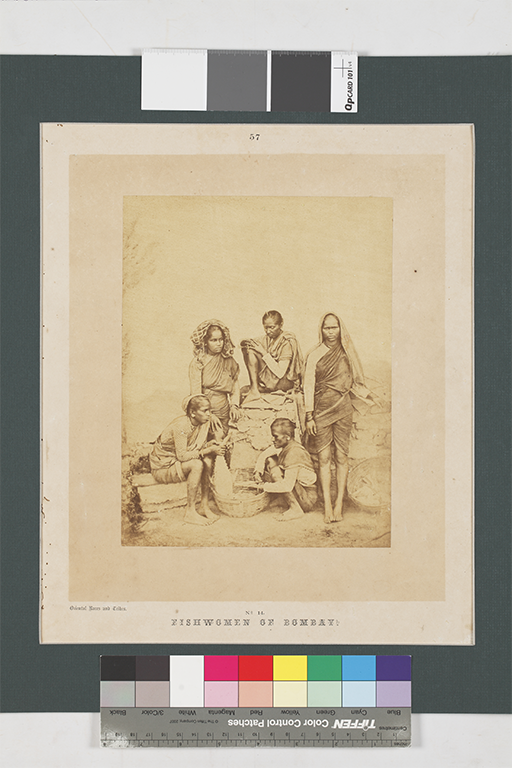

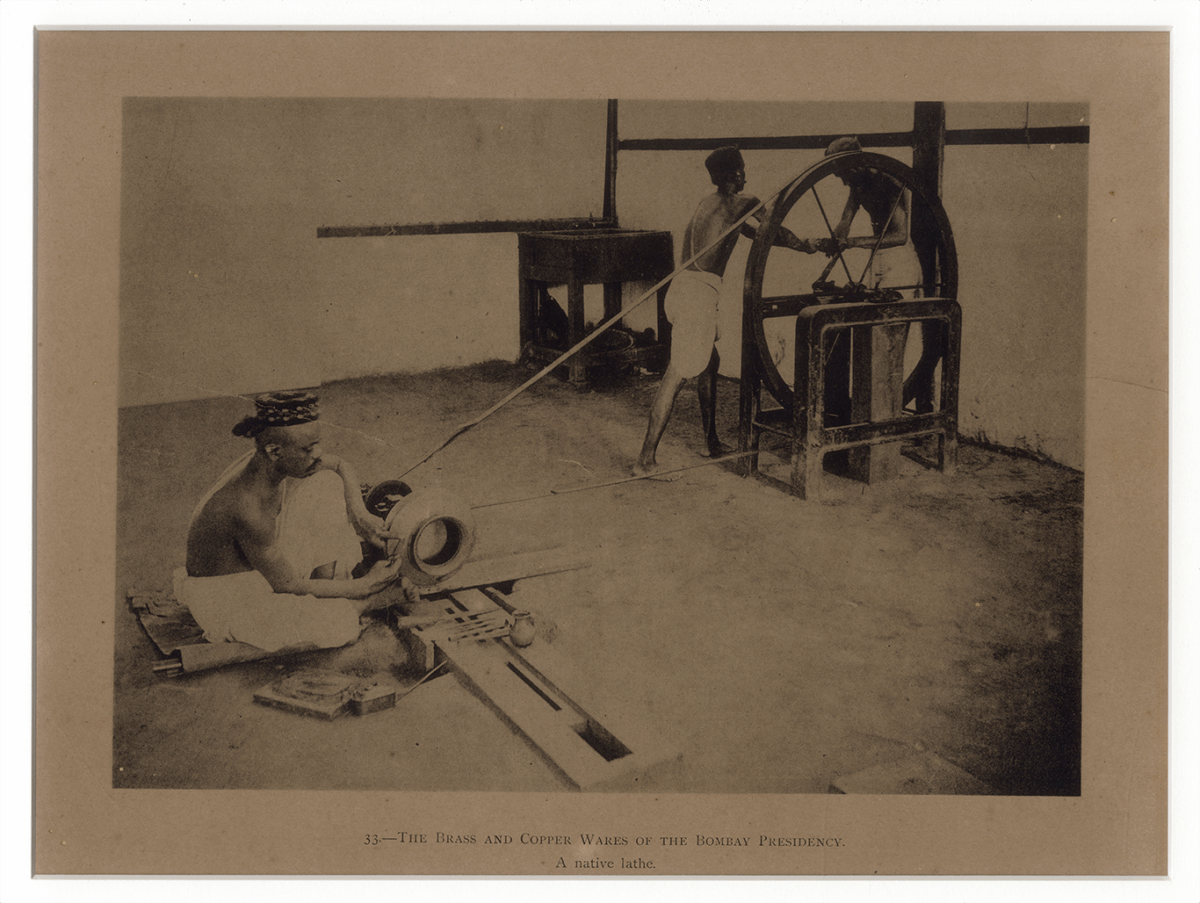

This essay marks four phases in twentieth-century Bombay. It touches upon the nationalist heyday of the late colonial period, coinciding with the interwar years and the eventual onset of deindustrialization in the postcolonial city as evidenced by the Great Textile Mill Strike (1982–83). In doing so, it delineates the popularity of the Shiv Sena, the ethno-regionalist, right-wing-organization-turned-political party, from the 1960s to the ushering in of neoliberal reforms and state-sponsored violence in the early 1990s. The photographs discussed showcase the distressing circumstances of the city’s working poor as they came knocking on the doors of the art school. They represent a departure from prior illustrative studies, many of which depict the laborer as inseparable from their craft. These earlier visual renderings not only are rigid caste-based occupational studies, but also commodify and group people and goods for the colonial economy.2This is both similar and in contrast to Deepali Dewan’s study of visual representations of the native craftsperson at work. See Dewan, “The Body at Work: Colonial Art Education and the Figure of the ‘Native Craftsman,’” in Confronting the Body: The Politics of Physicality in Colonial and Post-Colonial India, ed. James H. Mills and Satadru Sen (Anthem Press, 2004), 118–32. In this essay, Dewan writes about the complete absorption of the artisan in their labor of craftmaking, the decontextualizing of time and space, the assumptions around authenticity in the transference of the embodied knowledge/artistry onto their object, and their lineage from caste-based studies including Balthazar Solvyns, A Collection of Two Hundred and Fifty Coloured Etchings: Descriptive of the Manners, Customs and Dresses of the Hindoos (Calcutta: 1799) and other publications, such as the first issue of the Portfolio of Indian Art (London: 1881–[c. 1887?]), which features representational examples of photo-chromolithographic art published by William Griggs (1832–1911), who invented the process of photo-chromolithography, and The Journal of Indian Art and Industry (London: 1884–1917), which promoted the revival of Indian arts. While the unnamed subjects of these types of images are categorized as “Santal Mother, Girl, or Man,” “Fishwomen [sic] of Bombay” (the native Koli community), or “Palanquin Bearers, Bombay” (who were mainly Dalit Mahars), the bourgeois photographers who took them are identified and thus accorded authorship (figs. 2 and 3).3See Partha Mitter, The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1922–1947 (Reaktion Books, 2007), 29–31. This practice was taken up by art critic E. B. Havell (1861–1934), who was also the principal of the Government School of Art in Calcutta (present-day Kolkata). It was also emblematized by artists of the Bengal School, such as Jamini Roy (1887–1972) and Deviprosad Roy Chowdhury (1899–1975), and by proponents of the swadeshi nationalist movement in the early 20th century. Photographers such as Sunil Janah (1918–2012), who photographed famine victims and revolutionary laborers, in addition to making voyeuristic portraits of tribal women, carried this practice forward. For a layered understanding of indigeneity, class, nationalism, and modernism in Indian art, see Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (Tulika Books, 2020), 270–80; and Sanjukta Sunderason, Partisan Aesthetics: Modern Art and India’s Long Decolonization (Stanford University Press, 2020).

© Sarmaya Arts Foundation

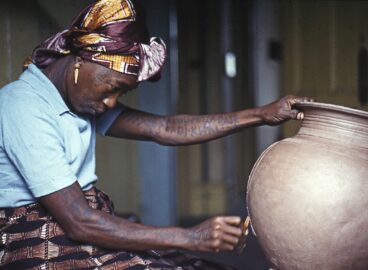

In the 20th century, as live models at JJ were placed in conversation with plaster casts of Greek sculptures, the worn human forms of the models underscored the stark valorization of art over labor. The photographs that capture this dichotomy evoke the continued incongruence between outmoded colonial art instruction and the parlous position of both fine artists and laborers at JJ and beyond.4Partha Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 1850–1922: Occidental Orientations (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 43. While nationalist sentiment swept through many aspects of life in the 1930s, the influx of Eurocentric methods extended unevenly to the temporary hiring of live models to proclaim an “authentic” Indian art. These live art sessions disembodied the model by decontextualizing and romanticizing the absented adivasi (tribal) figure or pious, religious woman as the symbolic native type, untainted by the trappings of colonial modernity (figs. 4 and 5).5Mitter, The Triumph of Modernism, 31. Mitter notes that “colonial anthropology created the myth of the timeless ‘noble savage,’ even as the imperial regime was suppressing the Santals through brutal counter-insurgency measures.” I add that violence against adivasis across India and their differentiated resistance and adaptation continued through the 20th century. Anonymized men and women assembled as native types bore witness to the canonization of carving, painting, etching, and setting in stone—that is, to the colonial practice of classifying and essentializing select communities.6Dewan, “The Body at Work,” 125. Dewan notes the romanticization of native craftspeople in colonial India compared to their European counterparts, who were already seen as lost to industrialization. While live models and art students were interminably devalued and alienated during deindustrialization, some of them, as seen in photographs by Vyarawalla and Singh, resisted being cast as the marginal figure by returning the subaltern gaze.

JJ was established in 1857 by cotton and opium merchant Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy (1783–1859) to provide relief to and upskill displaced migrant workers in what was a ruthlessly competitive colonial market. However, it eventually cultivated only a preferential, cultured class.7To follow these shifts in student compositions in art schools over time, see Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 29–62. On the one hand, though JJ facilitated commissions for artists to design sculptural forms in city structures, a detachment from and dismissal of Indian artistry steadily grew among the Indian art circuit in the late 19th century for various reasons, including the difficulty in cultivating a sustained patronage.8See N. M. Kelkar, The Story of the Sir J. J. School of Art (Government of Maharashtra and Sir J. J. School of Art, [1969]), 68–71, 94–95; and Suhas Bahulkar et al., eds. Encyclopaedia Visual Art of Maharashtra: Artists of the Bombay School and Art Institutions (Late 18th to Early 21st Century) (Pundole Art Gallery, 2021), 457–60. Particularly noteworthy are the agrarian figures sculpted by N. G. Pansare (1910–1968) on the walls of the Art Deco New India Assurance Building (then the Bombay Mutual Building) founded by industrialist Sir Dorabji Tata in Fort, Bombay, in 1919. As artisan and agrarian populations were compelled to migrate in large numbers to Bombay and engage in laborious work in textile mills, construction, shipping, and other manufacturing industries, their lives were upended on an unprecedented scale by colonial expansion.9See Prashant Kidambi, The Making of an Indian Metropolis: Colonial Governance and Public Culture in Bombay, 1890–1920 (Routledge, 2007), 171; Sheetal Chhabria, Making the Modern Slum: The Power of Capital in Colonial Bombay (University of Washington Press, 2019), 13; and Manu Goswami, Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space (University of Chicago Press, 2004), 60–61. On the other hand, while opportunities may have been available to some prospective students to apply to JJ, many of those gaining acceptance fell by the wayside as they faced extraordinary difficulties there, with only a handful later succeeding as fine artists.10Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 79. However, with concerted endeavors over time, JJ’s reputation improved, and students from other regions were able to avail of dedicated scholarships and thus to enroll.11Kelkar, Story of the Sir J.J. School of Art, 97.

JJ was premised on the bourgeois, individualistic apprenticeship structure that developed in response to industrialization in England and Europe from the mid-19th century onward. As with other colonial art schools in India, JJ exacerbated a sharp divide between traditional, familial, and community-based workshops and the colonial education system, which mandated English as the language of instruction with prerequisite training in geometry and arithmetic at the admissions stage.12Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 29–33, 35. These “reformist” requirements, along with education fees, systematically disqualified and disbarred poor and lower-caste artisans, thereby separating the field of craft from that of art. Even though craftspeople were considered important practitioners and knowledge-makers, they were viewed as mere copyists and only brought to art schools to exhibit their artistry and wares and assist students (fig. 6).13This Dhurandhar image depicts Brahmins (as evidenced by the janeu, or sacred thread men wear across their upper bodies), who do not indulge in manual labor and otherwise belong to the priestly/spiritual caste, making brassware. This could be because the rigid caste system accorded a certain Brahmin class/caste to professional brass-making for traditional temple wares and/or because they belonged to the Vishwakarmas or Vishwa Brahmins, a community of artisans who claim to descend from Vishwakarma, the Hindu divine figure of architecture and artisanship. For more images of the artisans brought to JJ, see W. E. Gladstone Solomon, The Bombay Revival of Indian Art: A Descriptive Account of the Indian Room Constructed and Decorated by the Staff and Students of the School of Art (Sir J. J. School of Art, 1924). Subsequently, an exclusive echelon of elite, upper-caste “gentleman” artists burgeoned as “intellectual tastemakers” at the colossal expense of artisans.14An extensive list of enrolled students notes primarily upper-caste names in the Catalogue of the Exhibition of Arts and Crafts in Aid of the Gladstone Solomon Scholarship Fund (Sir J. J. School of Art, 1936). In Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 37, 50, 55, this early dominance of the elite, upper-caste, and upper-class attending the school is highlighted. In addition, historian Ajantha Subramanian in The Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India (Harvard University Press, 2019), 27–29, notes that in colonial and postcolonial India, technical knowledge shifted from being the domain of lower-caste artisans to a tool of state power and upper-caste advancement. Engineering education, initially aimed at supporting dislocated artisans, excluded them and instead elevated upper castes with no prior technical background into prestigious professional roles. This was also reiterated in the recent commemorative show Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School, organized by DAG and Sir J. J. School of Art, Architecture and Design, March 7–April 20, 2025, https://dagworld.com/shifting-visions-exhibition-mumbai.html. Despite preliminary efforts to integrate them into the student body, artisans were apprehensive about foregoing their more dependable, albeit paltry agricultural earnings for non-remunerative education.15Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 30, 36–37, 54–58; Kelkar, Story of the Sir J. J. School of Art, 30–31; and Dewan, “The Body at Work,” 126. Over time, their absence was transferred, disincarnated, and disseminated by illustrated publications circulated at JJ.16Dewan, “The Body at Work,” 126–27. These texts were likely printed by lower-caste Muslim artisans who had moved to the transforming industrial center to adapt their skills at booming lithographic presses or at a paper mill in Girgaum. In Amanda Lanzillo, Pious Labor: Islam, Artisanship, and Technology in Colonial India (University of California Press, 2023), 2–3, Lanzillo argues how this community resisted their alienation in industrializing cities by moving and negotiating between family-run ateliers and capitalist setups in technical professions such as print labor, thereby consolidating their positions within North Indian society and migrant settlements elsewhere. See also Lanzillo, “Prison Papermaking: Colonial Ideals of Industrial Experimentation in India,” Technology and Culture 65, no. 1 (2024); and Arindam Dutta, The Bureaucracy of Beauty: Design in the Age of Its Global Reproducibility (Routledge, 2007), 232. These illustrated publications were also made by those who worked in related but bleak sites of industrial work, such as the colonial prison—a fortified enclosure in which prisoners were “disciplined and punished” through the extraction of their cheap labor. Hence, in the photographs taken at JJ by Vyarawalla, Nissen, and Singh, displaced migrant workers make spectral appearances as live objects in art education.

Colonial art schools promoted scientific drawing via human anatomy lessons, and for this purpose, plaster casts of Greek sculptures were favored over live models.17Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 34–35. In the late 1930s, JJ student and photographer Vyarawalla pictured her contemporaries Rehana Mogul and Mani Turner creating a sculpture exemplifying such principles, including clarity of view and precision of measurement (fig. 7). In this striking photograph, Turner (on the far right), bends forward with calipers in hand to ascertain the proportion of her subject’s upper leg. His waist is also cinched with a measuring tape. For Vyarawalla and her classmates, who came from a host of backgrounds, JJ was extolled as an artistic abode for experimentation in photography and freedom for women.18Sabeena Gadihoke writes that Vyarawalla, who had a restrictive, orthodox upbringing, enrolled at JJ in the late 1930s to earn a diploma in the Arts Teachers’ Course. See Gadihoke and Homai Vyarawalla, Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla (Parzor Foundation and Mapin Publishing, 2006), 17, 12–22. Vyarawalla learned photography independently with her partner, Manekshaw Vyarawalla. While Homai Vyarawalla found her vocation as a photojournalist, her female peers sought theirs in advertising, commercial art and design, printing, modeling, filmmaking, teaching, and journalism—or turned to marriage if they could not forge avenues to practice as fine artists full-time. It was also projected as the ground for the reinvention of Indian artists, including women, at a time of soaring nationalism in late colonial Bombay.19Sabeena Gadihoke, “Whatever Happened to Rehana? Homai Vyarawalla’s Photographs of Modern Girls and the Cultural Project of Nationalism,” Trans Asia Photography 2, no. 2 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1215/215820251_2-2-205. See also Sambhaji Kadam, “Indian Painting Today” [May 1970], trans. Nikhil Purohit, in Citragōṣṭa: Art Writings in Marathi (1930s–1960s), ed. Noopur Desai and Ashutosh Potdar (Sharjah Art Foundation, 2023), 73. In this essay, which first appeared in the May 1970 issue of the Marathi periodical Satyakatha, Kadam notes that the number of students who chose to study applied arts at JJ had increased exponentially as doing so was a viable means of livelihood, with female students enrolling in greater proportion than their male counterparts since the 1940s. The author also patronizingly acknowledges that even though women rarely became professional artists, they nonetheless could impart their knowledge of art for the greater good of society. As a female photographer and student, Vyarawalla cancels the male gaze and gives space to her female subjects, downgrading the male model’s status and labor.

Returning to the photograph, Mogul looks up, decidedly satisfied with her sculpture of the live, male model. While the work is not life-size, it is strategically located within the composition and thereby rendered the tallest figure. Thus, it is given prominence and a larger-than-life stature in the high-ceilinged JJ studio. Just as he posed for hours for the sculpting session, the model was forced to stand still as a photographed subject; nonetheless, he looks straight at the camera, holding our gaze.20It is unclear whether the model was compensated for the additional task of posing for such photography sessions.

The live model enacts the queries of renowned British industrial design educator Henry Cole (1808–1882). After the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, a world’s fair that heralded the colonial empire as the global pioneer in processing and harboring goods from around the world, Cole interrogated the worth of artisans. He questioned whether artisans should be expected to function as automated machines as per their employers’ demands, whether the commercial aspect of their labor could be compromised for skilled creations, and whether manufacturers recognized this and, moreover, were willing to invest money in educating artisans in order to foster a more skilled labor force.21Dutta, The Bureaucracy of Beauty, 1–2. In figure 7, however, there is a split—the live model, who is no longer an artisan and thus deterritorialized, is at the service of Vyarawalla, Mogul, and Turner’s education. Yet, he does not entirely subdue himself to the machinery of sculpture-making and photography.

Vyarawalla directs a twofold production in which the live model has been relegated to a specimen, while Mogul and Turner are enhanced as artists. The deskilled laborer is utilized as raw material for a sculpture and thereby demarcated from the artists, who pay him no heed. Thus, a neat and graded symmetry unravels itself. While both Mogul and the sculpture as a finished product occupy the foreground, the model and Turner are arranged in the background to demonstrate various stages of sculpting. The two female sculptors are on either side, absorbed and tending to their respective props, one artificial but more exalted than the human male model.

The model is not lionized like a permanent fixture of JJ, such as the plaster casts of Greek sculptures or the students’ sculpted figurines, but instead beckoned to JJ whenever there is a need for his muted and sampled presence. He represents an eerie and curious amalgam of the “native type” and the Greek ideal but still stands out.22“Native type” imagery proliferated in the magisterial photographic series of ethnographic studies titled The People of India: A Series of Photographic Illustrations, with Descriptive Letterpress, of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan (1868–75) and, more specifically, in The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay (1863–66) by William Johnson (figs. 2 and 3) and William Henderson, alongside art made by colonial and Indian artists and photographers as previously mentioned. His look, which evinces personhood and a cynical consciousness, defies and pierces the composition, as he does not conform to an anonymized live model. 23See Goswami, Producing India, 109–16. His gritty stare reflects the long-standing labor networks of caste, kinship, and village through which single male workers, like him, navigated the workplace and neighborhood in a fluctuating economy.24See Rajnarayan Chandavarkar, “From Neighborhood to Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Left in Bombay’s Girangaon in the Twentieth Century,” introduction to One Hundred Years, One Hundred Voices: The Millworkers of Girangaon: An Oral History, ed. Neera Adarkar and Meena Menon (Seagull Books, 2004), 14, 28–30. In this regard, the long stick that he holds—archetypal of idealized “native type” imagery—comes into view in figure 8.25Zaen Alkazi, “The Militarization of Labour Politics in Interwar South Asia: Paramilitaries and Claims-Making Among Bombay’s Textile and Dalit Workers, c. 1920–1940,” International Review of Social History, posted online by Cambridge University Press, September 9, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859025100771. The exploited display of the model’s stripped body and crewcut belies his likely association with an akhara (body-building gymnasium), a prominent recruiting ground to militarize labor volunteers from the Maratha, Mahar, and Muslim weaver mill population, as many had gained leverage and respite from casteism in the British Indian Army. They symbolized the enduring martial prowess of the 17th-century Maratha ruler Shivaji to reassert military pride and caste uplift in Bombay’s potent interwar labor and class politics, using lathis (long bamboo sticks) to attack and defend. The man’s encounter at JJ underpins the grave situation of “mobile incarceration,” whereby badli (temporary) workers would have been picked from designated spots in the city and brought to the school to earn an income.26I borrow the term “mobile incarceration” from Goswami, Producing India, 103–31. In Bombay, during labor strikes, the recruiting pool of daily wage laborers increased.

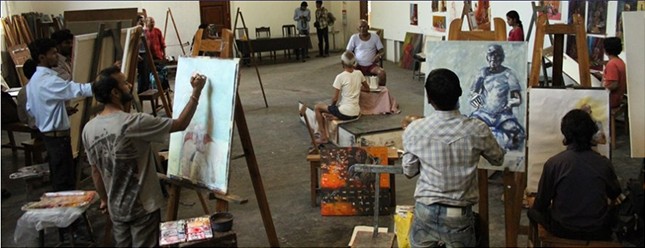

A formalist and painterly rendition of a sketching session attended by mostly male students, with a few female students scattered across the class, is framed by Vyarawalla in figure 9.27Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 53. Mitter observes that art schools in the United Kingdom, well into the late 20th century, discouraged women from applying for painting and sculpture, because, as they were told, they were better suited for applied arts. In this image, a sari-clad woman seated on a raised platform encircled by the students models with her hands clasped on her lap and her body on silent display. Though this is the only photograph of a live, clothed female model discussed here, women often modeled nude at JJ.28At the recently concluded exhibition at JJ, student M. V. Athavale’s voyeuristic 1927 etching of a gaunt woman model posing nude, wearing only bangles and with her back turned—and the accompanying curatorial note—attests to this method. See “Portrait and Figure Study” and M. V. Athavale, Untitled, DAG website, Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School exhibition page, https://dagworld.com/shifting-visions-exhibition-mumbai.html. Students were believed to have expressed excitement during such classes, when female labor modeled nude. See also Bahulkar et al., Encyclopaedia Visual Art of Maharashtra, 143.

The Postcolonial Moment

Forty years later, three male students engrave busts modeled after a middle-aged man sitting slouched on a raised platform (fig. 10), a scene captured by Foy Nissen, the prolific photographer, writer, and amateur historian of Bombay who was of Danish origin. This oblique composition captures the static disembodiment of the alienated model, who stares vacantly into a clutter of half-open and half-closed window shutters.29In this photograph, the live model’s existence subverts and merges with Walter Benjamin’s concept of “empty, homogenous time,” a utopian and linear progression in the post-nationalist city, in conjunction with Henri Lefebvre’s understanding that space is heterogenous and shaped by capitalism as well as by social processes and relations. This discussion on concepts of space, time, and labor is cited in Goswami, Producing India, 34–35, and is vital to understanding this image, especially in relation to the photographer’s own comments on his practice: “For me, there is no such thing as the definitive photograph. The very act of fixing an image in a split- shutter-second suggests the dialogue that may ensue. . . . Does the subsequent viewer see it this way? Or have I missed something vital and telling.” See Foy Nissen, “The Solitary Moment,” Foy Nissen: The Quiet Genius website, https://foynissen.com/article/the-solitary-moment/. An unaligned and haphazard path of abject unemployment and deindustrialization stretches out before the live model, whose corporeal presence is as bereft and hollow as the sculptures underway.30For a distinct exploration of deindustrialization and the impact of the Five-Year-Plans on the artisanal population in the post-Independence period through the Great Textile Mill Strike and after, see Ashish Rajadhyaksha, “‘Make Every Indian a Creator of Intellectual Property’: Mumbai’s Casual Labour as a Creative Class,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 15, no. 4 (2014): 608–24, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2014.975401. He ekes out a living as an expendable live model, a still life always in supply. At the same time, we can discern some changes in the student composition at JJ in the late 20th century.31“Aamchi Mumbai’s ‘Sir JJ School of Art’ Alumnus Inspires Budding Artists in Namma Mysuru,” Star of Mysore, March 16, 2021. Here, a woman alumna from Mangalore who enrolled in the drawing course at JJ in the late 1960s and spent five years attending the school and living with her extended family in the city, was advised to look for jobs as a textile designer and in the printing press before she secured work at the government television broadcaster Doordarshan as a visual artist in 1973. Kajri Jain in Gods in the Bazaar: The Economy of Indian Calendar Art (Duke University Press, 2004), 152–58, describes how student dynamics have varied in the 20th century with the success of S. M. Pandit (1916–1993), who was from an artisan background. However, Juned Shaikh in Outcaste Bombay: City Making and the Politics of the Poor (University of Washington Press, 2021), 107, writes about Dalit artist and prospective JJ student Ramesh Haralkar, who painted banners for the Dalit Panthers in the early 1970s. Haralkar, the son of a conservancy worker, could not fulfill his dream of attending JJ because he had to make the hard decision to accept government housing allotted by the Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC), which confined him to his caste profession as a city sanitary worker. Susan Bean, “Vernacular Sculptors Shaping Modern India’s Artscape—Jadunath Pal and G. K. Mhatre,” in “Indian Ceramic: History and Practice,” special issue, Marg 69, no. 2 (2017–18): 22–26, lays out an important comparison between Pal and Mhatre’s respective artistic trajectories at the turn of the 20th century, when the former, as a low-caste Kumbhakar (potter) was “relegated” to being an artisan in Bengal, whereas Mhatre, as an upper-caste Somvanshiya Pathare Prabhu, was recognized as an artist in Bombay—though both came from clay-modeling families. For an exhaustive range of JJ alumni profiles, see Bahulkar et al., Encyclopaedia Visual Art of Maharashtra.

In 1955, steps were taken to make the art school more inclusive, with 5 percent of seats reserved for candidates from socially and economically disadvantaged backgrounds (“Backward Classes”) based on an entrance test.32“J. J. School of Art,” Times of India, January 24, 1955. In 1954, caste-based reservations in higher education were introduced to address historical disadvantages faced by Scheduled Castes (SCs), who were also categorized as “Backward Classes.” Following an arduous struggle by the diverse political base of the Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti (Unification of Maharashtra Committee), the State of Maharashtra was formed along linguistic lines, with Bombay as its capital in 1960. However, from the late 1960s onward, the Shiv Sena’s regionalist but wide socioeconomic membership, goaded by its middle-class leadership and driven by increasing financial instability in Bombay, violently advocated for and took direct action to secure ethnicity-based job reservations for the local Marathi population.33See Kapilacharya, “Shiv Sena Speaks: An Official Statement,” ed. Bal K. Thackeray (Marmik Cartoon Weekly Office, 1967); and Sudha Gogate, The Emergence of Regionalism in Mumbai: History of the Shiv Sena (Popular Prakashan, 2014); and Gyan Prakash, Mumbai Fables(Princeton University Press, 2010). Since 1970, JJ has instituted monthly scholarships and fee exemptions for students, thus attracting a broader pool of applicants.

However, in 1984, the year in which Nissen’s photograph was shot, Bombay was marked by two imbricated major events: The nationwide imposition of the Emergency (1975–77), when emergency powers were applied across the country, paved the way for the brutal sundering of robust labor politics and history in the city.34Bombay had a long, effective, and checkered history of labor politics associated with its textile mills from the 1920s through the Great Textile Mill Strike in 1982. The 1982 strike was clamped down on by mill owners, who refused to accede to workers’ demands for higher wages, leading to the dismantling of both the mills and trade union politics. See Chandavarkar, “From Neighborhood to Nation,” 28–77. This was ramified by the Great Textile Mill Strike, which accelerated neoliberal reforms.35Chandavarkar, “From Neighborhood to Nation,” 8. See also Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratinav Anil, India’s First Dictatorship: The Emergency, 1975–1977 (Oxford University Press, 2021), 446; and H. van Wersch, The Bombay Textile Strike, 1982–83 (Oxford University Press, 1992). After this labor stoppage, mills in the city shuttered, driving more than a hundred thousand workers into casual, informal employment. In this atmosphere of economic uncertainty, scores of disenchanted Marathi workers were galvanized and girded by the right-wing, anti-migrant, and anti-Muslim rhetoric of the Shiv Sena.

Color and a Postmodern Critique

The pall of deindustrialization hangs heavy in the downcast eyes and static body of the elderly live model captured by Raghubir Singh in figure 11.36Raghubir Singh and V. S. Naipaul, Bombay: Gateway of India (Aperture, 1994), 9. In conversation with the controversial Trinidadian-born British writer of Indian descent V. S. Naipaul (1932–2018), Singh shares his thoughts on the dichotomy between the optimism exuded by deprived migrants and the city’s “inability” to cater to them. Singh’s modernist aesthetic, which was inspired by American documentary photographers and the French photographer Henri Cartier Bresson (1908–2004), is also an extension of the worldview of human-interest stories promoted by the international photo agency Magnum Photos. Naipaul observes that the photographer chronicled milieux that were deeper and subtler than straightforward documentations of protest. In response, Singh acknowledges the importance of Naipaul’s revelatory travelogue India—A Million Mutinies Now (1990) on his work. A dire juncture at JJ is presented via this photograph of an emaciated, aging man who, seemingly diminished and disenfranchised, is clad in an oversized kurta, dhoti, and turban. His frail and bent frame is at odds with the plaster casts of classical, nude Greek male sculptures symbolizing Eurocentric ideals of the male form that surround him. Moreover, the color photograph offers an incisive reading of the problematic continuation of this “educational” tradition and artisanal and scholastic disempowerment at JJ well into the late 20th century.37Mia Fineman et al., Raghubir Singh: Modernism on the Ganges, exh. cat. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017), 21–29. Singh, who went back to the chromogenic printing process in his later career, had early access to color film because of his work for National Geographic and other international publications at a time when it was not available in India due to trade restrictions, and he was an early proponent of it when it was still largely looked down upon by documentary photographers. See also, Julian Stallabrass, “Knowledge, Nation and Colour in the Documentary Photography of Luigi Ghirri, Raghubir Singh and Susan Meiselas,” in Art and Knowledge after 1900: Interactions between Modern Art and Thought, ed. James Fox and Vid Simoniti (Manchester University Press, 2023), 21. In Max Kozloff, “An Interview with Raghubir Singh,” Asian Art 2, no. 4 (1989): 15, Singh shares that he was always “interested in the documentary aspect of color,” 15.

Singh composed this aberrant scene to unsettle notions of colonial grandeur and to foreground its oppressive hangover in the lackluster confines of JJ. The ongoing, ill-fitting presence at JJ in 1991 of casts of Greek nude sculptures tells us of its unrelenting durée in the postcolonial city. Singh has orchestrated a disharmony between these two teaching aids—the live model, an “ethnographic type” (again holding a stick) of which he was critical, and Greek sculpture—and that of art students, who represent a third category. The students are not portrayed as dutifully immersed in a conventional classroom setting; instead, like the model, they stay on, compelled to “wait” and remain on-site.

The young male student pictured with slumped shoulders and his hands on his back evokes restlessness and unease. He is seemingly caught unawares, despite the reassuring hand of a friend on his shoulder. The intrusive photographer draws us in, setting up a trenchant triangular network of gazes as he inhabits the place of student-artist and intervenes as scathing outsider-spectator—in effect, creating a visual critique that extends beyond the male student in the photograph to encompass the general dissent among students and alumni regarding outmoded education at JJ, among other issues. He constructs a postmodern critique, arresting the apparent friction at JJ by transfixing the male student’s consternation and awkward stance within his own field of view.38This direct confrontation is ubiquitous in his Bombay work. See Singh and Naipaul, Bombay: Gateway of India, 6. In his interview with V. S. Naipaul, Singh mentions that his Bombay photographs look “straight into people. My other books don’t do that, as much as the Bombay work does. This work is direct. There is more confrontation and tension.” Both the institution and its students faced numerous obstacles well into the 20th century—including the unaffordability of art materials, a dearth of faculty, low attendance, outdated teaching methods, a lack of residential facilities for students, and even an attempt to close the school.39Kelkar, Story of the Sir J.J. School of Art, 30–31. See Jerry Pinto, Citizen Gallery: The Gandhys of Chemould and the Birth of Modern Art in Bombay (Speaking Tiger, 2022), 208, for a cited reference of art historian Jyotindra Jain’s disillusionment and frustration with the colonial art lessons that he was exposed to as a student at JJ in the late 1960s. F. N. Souza, the polemical founder of the Progressives/ Progressive Artists Group (PAG), is quoted as being staunchly disapproving of what he believed to be the low quality of students and shows churned out by JJ and the Bombay Art Society. In 1984, he recalled that their art suffered from a crisis of imagination and a disconnect from the present, and that the radical foundation of the PAG at the turn of Independence was a reactionary move away from artistic orthodoxy of the human form. See Souza, “Progressive Artists Group,” Patriot Magazine, February 12, 1984; quoted in Yashodhara Dalmia, The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives (Oxford University Press, 2001), 42. See also Pralhad Anant Dhond, “Scheme to Shut Down the School of Art” [1968], trans. Sohnee Harshey, in Citragōṣṭa, 167–72, an article that first appeared in a 1968 issue of the Marathi periodical titled Roopa Bheda; and “J. J. art exhibition sub-standard,” Times of India, February 25, 1983. JJ’s website also notes several faculty and administrative vacancies; see “Members of Faculty,” Sir JJ School of Art, Mumbai website, https://www.sirjjschoolofart.in/departments/members-of-faculty. The apparent wariness of the confounded student and the constrictive environment speak to the repeated demands of students and alumni to revise syllabi, upgrade infrastructure, and introduce English-language tutoring. In the course of time, some of these measures were undertaken.40Nina Martyris, “JJ School hopes to find old spark with a little help from new friends,” Times of India, October 6, 2002; “Work on JJ school begins,” ibid., March 6, 2004; and Bella Jaisinghani, “JJ School of Art Syllabus set to change course,” ibid., September 25, 2009. For the most recent comprehensive but staggering list of “deficiencies” at JJ, see the All India Council for Technical Education, “Approval Process 2023–24 [. . .],” https://www.sirjjschoolofart.in/uploads/editor-images/AICTE%20Aproval%20Report%202023-2024.pdf.

The continued veneration and aegis of objects over labor at JJ tie together labor and education through the disparate gazes and positions held by the photographed subjects whom Vyarawalla, Nissen, and Singh capture and bring to our attention. Their photographs unfold the dynamics and impact of art education and labor beyond the precincts of the art school, highlighting the convergence of social inequities and the scarcity of resources.41By 1994, JJ had implemented a 50 percent reservation of seats. See “Reservation of Seats,” Sir J. J. School of Art, Mumbai website, https://www.sirjjschoolofart.in/programmes-info/reservation-of-seats. They infer a narrative of the reverberating consequences of colonial knowledge and the concomitant making and entrenching of hierarchies, in which the resources necessary for artmaking became privileged enclaves unto their own, with hardly any public or private intervention. The indigent labor of the city has continued to serve as live models well into the present day, as demonstrated by photographs on JJ’s website (figs. 1a and 1b).42Pallavi Smart, “Exhibition at Mumbai’s Sir JJ School of Art gives glimpse into evolution of art education in India,” Indian Express [Mumbai], March 11, 2025. Disaggregated, disarmed, and appropriated by art schools, artmaking, and the accumulation of capital in the city at large, the below-minimum wages paid to said live models were recently upgraded.43Niraj Pandit, “JJ School of Art Models Get a Pay Hike of ₹200–500 after a Decade,” Hindustan Times, December 24, 2024.

The JJ studio portraits encapsulate interconnected points of disproportionate modernity in a city teetering on the precipice of chronic unrest. They are distinct traces enunciating the poignant state of affairs within the school’s lofty walls and sunlit, capacious interiors for live models and students. Though monumental scale allows for the bodily autonomy of labor and studenthood in Vyarawalla and Singh’s photos (figs. 7, 8, and 11), in figure 9, by Vyarawalla, they are dwarfed and made a diminutive spectacle of. The photos by Nissen and Singh (figs. 10 and 11) show a consistent decline in both sitters. Together, as apparitions, they carry the burden of coerced historical experience, enduring the industrial capital model upon leaving a stagnant rural economy. Thus, the drawn-out process of mill closures, the protracted affair of deterritorialization and depoliticization of the urban poor, and the hastening of liberalization and right-wing propaganda—enabled by the Emergency—were inextricably coterminous with the pedagogical inertia of JJ. 44See Thomas Blom Hansen, Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay (Princeton University Press, 2001). In 1992, a year after Singh took the image at JJ, the city was engulfed in anti-Muslim riots in response to the demolition of the Babri Masjid, a mosque in Ayodhya. These attacks were led by vast sections of the lower caste and poor, with the active engineering of upper-caste and middle-class members of the Shiv Sena, enmeshed with powerful political and business interests in the city. Between 1995 and 1996, Bombay was renamed “Mumbai” to symbolize a reclamation of the city by the local Maharashtrian population. See also Goswami, Producing India, 12. In late 2023, JJ was granted “deemed university status,” a move welcomed by alumni as it ensured the institution would offer a “world-class education,” including adequate student residential accommodation. Others have stated that the proposed fee hikes associated with this new status will deter economically disadvantaged individuals from applying. See H. T. Correspondent, “Sir J J School of Art and Architecture to Become Deemed University,” Hindustan Times, June 29, 2023.

- 1This study shows how neither the photographs nor the discussions they provoke are bookended spatiotemporally by these decades.

- 2This is both similar and in contrast to Deepali Dewan’s study of visual representations of the native craftsperson at work. See Dewan, “The Body at Work: Colonial Art Education and the Figure of the ‘Native Craftsman,’” in Confronting the Body: The Politics of Physicality in Colonial and Post-Colonial India, ed. James H. Mills and Satadru Sen (Anthem Press, 2004), 118–32. In this essay, Dewan writes about the complete absorption of the artisan in their labor of craftmaking, the decontextualizing of time and space, the assumptions around authenticity in the transference of the embodied knowledge/artistry onto their object, and their lineage from caste-based studies including Balthazar Solvyns, A Collection of Two Hundred and Fifty Coloured Etchings: Descriptive of the Manners, Customs and Dresses of the Hindoos (Calcutta: 1799) and other publications, such as the first issue of the Portfolio of Indian Art (London: 1881–[c. 1887?]), which features representational examples of photo-chromolithographic art published by William Griggs (1832–1911), who invented the process of photo-chromolithography, and The Journal of Indian Art and Industry (London: 1884–1917), which promoted the revival of Indian arts.

- 3See Partha Mitter, The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1922–1947 (Reaktion Books, 2007), 29–31. This practice was taken up by art critic E. B. Havell (1861–1934), who was also the principal of the Government School of Art in Calcutta (present-day Kolkata). It was also emblematized by artists of the Bengal School, such as Jamini Roy (1887–1972) and Deviprosad Roy Chowdhury (1899–1975), and by proponents of the swadeshi nationalist movement in the early 20th century. Photographers such as Sunil Janah (1918–2012), who photographed famine victims and revolutionary laborers, in addition to making voyeuristic portraits of tribal women, carried this practice forward. For a layered understanding of indigeneity, class, nationalism, and modernism in Indian art, see Geeta Kapur, When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (Tulika Books, 2020), 270–80; and Sanjukta Sunderason, Partisan Aesthetics: Modern Art and India’s Long Decolonization (Stanford University Press, 2020).

- 4Partha Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 1850–1922: Occidental Orientations (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 43.

- 5Mitter, The Triumph of Modernism, 31. Mitter notes that “colonial anthropology created the myth of the timeless ‘noble savage,’ even as the imperial regime was suppressing the Santals through brutal counter-insurgency measures.” I add that violence against adivasis across India and their differentiated resistance and adaptation continued through the 20th century.

- 6Dewan, “The Body at Work,” 125. Dewan notes the romanticization of native craftspeople in colonial India compared to their European counterparts, who were already seen as lost to industrialization.

- 7To follow these shifts in student compositions in art schools over time, see Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 29–62.

- 8See N. M. Kelkar, The Story of the Sir J. J. School of Art (Government of Maharashtra and Sir J. J. School of Art, [1969]), 68–71, 94–95; and Suhas Bahulkar et al., eds. Encyclopaedia Visual Art of Maharashtra: Artists of the Bombay School and Art Institutions (Late 18th to Early 21st Century) (Pundole Art Gallery, 2021), 457–60. Particularly noteworthy are the agrarian figures sculpted by N. G. Pansare (1910–1968) on the walls of the Art Deco New India Assurance Building (then the Bombay Mutual Building) founded by industrialist Sir Dorabji Tata in Fort, Bombay, in 1919.

- 9See Prashant Kidambi, The Making of an Indian Metropolis: Colonial Governance and Public Culture in Bombay, 1890–1920 (Routledge, 2007), 171; Sheetal Chhabria, Making the Modern Slum: The Power of Capital in Colonial Bombay (University of Washington Press, 2019), 13; and Manu Goswami, Producing India: From Colonial Economy to National Space (University of Chicago Press, 2004), 60–61.

- 10Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 79.

- 11Kelkar, Story of the Sir J.J. School of Art, 97.

- 12Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 29–33, 35.

- 13This Dhurandhar image depicts Brahmins (as evidenced by the janeu, or sacred thread men wear across their upper bodies), who do not indulge in manual labor and otherwise belong to the priestly/spiritual caste, making brassware. This could be because the rigid caste system accorded a certain Brahmin class/caste to professional brass-making for traditional temple wares and/or because they belonged to the Vishwakarmas or Vishwa Brahmins, a community of artisans who claim to descend from Vishwakarma, the Hindu divine figure of architecture and artisanship. For more images of the artisans brought to JJ, see W. E. Gladstone Solomon, The Bombay Revival of Indian Art: A Descriptive Account of the Indian Room Constructed and Decorated by the Staff and Students of the School of Art (Sir J. J. School of Art, 1924).

- 14An extensive list of enrolled students notes primarily upper-caste names in the Catalogue of the Exhibition of Arts and Crafts in Aid of the Gladstone Solomon Scholarship Fund (Sir J. J. School of Art, 1936). In Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 37, 50, 55, this early dominance of the elite, upper-caste, and upper-class attending the school is highlighted. In addition, historian Ajantha Subramanian in The Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India (Harvard University Press, 2019), 27–29, notes that in colonial and postcolonial India, technical knowledge shifted from being the domain of lower-caste artisans to a tool of state power and upper-caste advancement. Engineering education, initially aimed at supporting dislocated artisans, excluded them and instead elevated upper castes with no prior technical background into prestigious professional roles. This was also reiterated in the recent commemorative show Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School, organized by DAG and Sir J. J. School of Art, Architecture and Design, March 7–April 20, 2025, https://dagworld.com/shifting-visions-exhibition-mumbai.html.

- 15Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 30, 36–37, 54–58; Kelkar, Story of the Sir J. J. School of Art, 30–31; and Dewan, “The Body at Work,” 126.

- 16Dewan, “The Body at Work,” 126–27. These texts were likely printed by lower-caste Muslim artisans who had moved to the transforming industrial center to adapt their skills at booming lithographic presses or at a paper mill in Girgaum. In Amanda Lanzillo, Pious Labor: Islam, Artisanship, and Technology in Colonial India (University of California Press, 2023), 2–3, Lanzillo argues how this community resisted their alienation in industrializing cities by moving and negotiating between family-run ateliers and capitalist setups in technical professions such as print labor, thereby consolidating their positions within North Indian society and migrant settlements elsewhere. See also Lanzillo, “Prison Papermaking: Colonial Ideals of Industrial Experimentation in India,” Technology and Culture 65, no. 1 (2024); and Arindam Dutta, The Bureaucracy of Beauty: Design in the Age of Its Global Reproducibility (Routledge, 2007), 232. These illustrated publications were also made by those who worked in related but bleak sites of industrial work, such as the colonial prison—a fortified enclosure in which prisoners were “disciplined and punished” through the extraction of their cheap labor.

- 17Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 34–35.

- 18Sabeena Gadihoke writes that Vyarawalla, who had a restrictive, orthodox upbringing, enrolled at JJ in the late 1930s to earn a diploma in the Arts Teachers’ Course. See Gadihoke and Homai Vyarawalla, Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla (Parzor Foundation and Mapin Publishing, 2006), 17, 12–22. Vyarawalla learned photography independently with her partner, Manekshaw Vyarawalla. While Homai Vyarawalla found her vocation as a photojournalist, her female peers sought theirs in advertising, commercial art and design, printing, modeling, filmmaking, teaching, and journalism—or turned to marriage if they could not forge avenues to practice as fine artists full-time.

- 19Sabeena Gadihoke, “Whatever Happened to Rehana? Homai Vyarawalla’s Photographs of Modern Girls and the Cultural Project of Nationalism,” Trans Asia Photography 2, no. 2 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1215/215820251_2-2-205. See also Sambhaji Kadam, “Indian Painting Today” [May 1970], trans. Nikhil Purohit, in Citragōṣṭa: Art Writings in Marathi (1930s–1960s), ed. Noopur Desai and Ashutosh Potdar (Sharjah Art Foundation, 2023), 73. In this essay, which first appeared in the May 1970 issue of the Marathi periodical Satyakatha, Kadam notes that the number of students who chose to study applied arts at JJ had increased exponentially as doing so was a viable means of livelihood, with female students enrolling in greater proportion than their male counterparts since the 1940s. The author also patronizingly acknowledges that even though women rarely became professional artists, they nonetheless could impart their knowledge of art for the greater good of society.

- 20It is unclear whether the model was compensated for the additional task of posing for such photography sessions.

- 21Dutta, The Bureaucracy of Beauty, 1–2.

- 22“Native type” imagery proliferated in the magisterial photographic series of ethnographic studies titled The People of India: A Series of Photographic Illustrations, with Descriptive Letterpress, of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan (1868–75) and, more specifically, in The Oriental Races and Tribes, Residents and Visitors of Bombay (1863–66) by William Johnson (figs. 2 and 3) and William Henderson, alongside art made by colonial and Indian artists and photographers as previously mentioned.

- 23See Goswami, Producing India, 109–16.

- 24See Rajnarayan Chandavarkar, “From Neighborhood to Nation: The Rise and Fall of the Left in Bombay’s Girangaon in the Twentieth Century,” introduction to One Hundred Years, One Hundred Voices: The Millworkers of Girangaon: An Oral History, ed. Neera Adarkar and Meena Menon (Seagull Books, 2004), 14, 28–30.

- 25Zaen Alkazi, “The Militarization of Labour Politics in Interwar South Asia: Paramilitaries and Claims-Making Among Bombay’s Textile and Dalit Workers, c. 1920–1940,” International Review of Social History, posted online by Cambridge University Press, September 9, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020859025100771. The exploited display of the model’s stripped body and crewcut belies his likely association with an akhara (body-building gymnasium), a prominent recruiting ground to militarize labor volunteers from the Maratha, Mahar, and Muslim weaver mill population, as many had gained leverage and respite from casteism in the British Indian Army. They symbolized the enduring martial prowess of the 17th-century Maratha ruler Shivaji to reassert military pride and caste uplift in Bombay’s potent interwar labor and class politics, using lathis (long bamboo sticks) to attack and defend.

- 26I borrow the term “mobile incarceration” from Goswami, Producing India, 103–31. In Bombay, during labor strikes, the recruiting pool of daily wage laborers increased.

- 27Mitter, Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 53. Mitter observes that art schools in the United Kingdom, well into the late 20th century, discouraged women from applying for painting and sculpture, because, as they were told, they were better suited for applied arts.

- 28At the recently concluded exhibition at JJ, student M. V. Athavale’s voyeuristic 1927 etching of a gaunt woman model posing nude, wearing only bangles and with her back turned—and the accompanying curatorial note—attests to this method. See “Portrait and Figure Study” and M. V. Athavale, Untitled, DAG website, Shifting Visions: Teaching Modern Art at the Bombay School exhibition page, https://dagworld.com/shifting-visions-exhibition-mumbai.html. Students were believed to have expressed excitement during such classes, when female labor modeled nude. See also Bahulkar et al., Encyclopaedia Visual Art of Maharashtra, 143.

- 29In this photograph, the live model’s existence subverts and merges with Walter Benjamin’s concept of “empty, homogenous time,” a utopian and linear progression in the post-nationalist city, in conjunction with Henri Lefebvre’s understanding that space is heterogenous and shaped by capitalism as well as by social processes and relations. This discussion on concepts of space, time, and labor is cited in Goswami, Producing India, 34–35, and is vital to understanding this image, especially in relation to the photographer’s own comments on his practice: “For me, there is no such thing as the definitive photograph. The very act of fixing an image in a split- shutter-second suggests the dialogue that may ensue. . . . Does the subsequent viewer see it this way? Or have I missed something vital and telling.” See Foy Nissen, “The Solitary Moment,” Foy Nissen: The Quiet Genius website, https://foynissen.com/article/the-solitary-moment/.

- 30For a distinct exploration of deindustrialization and the impact of the Five-Year-Plans on the artisanal population in the post-Independence period through the Great Textile Mill Strike and after, see Ashish Rajadhyaksha, “‘Make Every Indian a Creator of Intellectual Property’: Mumbai’s Casual Labour as a Creative Class,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 15, no. 4 (2014): 608–24, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2014.975401.

- 31“Aamchi Mumbai’s ‘Sir JJ School of Art’ Alumnus Inspires Budding Artists in Namma Mysuru,” Star of Mysore, March 16, 2021. Here, a woman alumna from Mangalore who enrolled in the drawing course at JJ in the late 1960s and spent five years attending the school and living with her extended family in the city, was advised to look for jobs as a textile designer and in the printing press before she secured work at the government television broadcaster Doordarshan as a visual artist in 1973. Kajri Jain in Gods in the Bazaar: The Economy of Indian Calendar Art (Duke University Press, 2004), 152–58, describes how student dynamics have varied in the 20th century with the success of S. M. Pandit (1916–1993), who was from an artisan background. However, Juned Shaikh in Outcaste Bombay: City Making and the Politics of the Poor (University of Washington Press, 2021), 107, writes about Dalit artist and prospective JJ student Ramesh Haralkar, who painted banners for the Dalit Panthers in the early 1970s. Haralkar, the son of a conservancy worker, could not fulfill his dream of attending JJ because he had to make the hard decision to accept government housing allotted by the Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC), which confined him to his caste profession as a city sanitary worker. Susan Bean, “Vernacular Sculptors Shaping Modern India’s Artscape—Jadunath Pal and G. K. Mhatre,” in “Indian Ceramic: History and Practice,” special issue, Marg 69, no. 2 (2017–18): 22–26, lays out an important comparison between Pal and Mhatre’s respective artistic trajectories at the turn of the 20th century, when the former, as a low-caste Kumbhakar (potter) was “relegated” to being an artisan in Bengal, whereas Mhatre, as an upper-caste Somvanshiya Pathare Prabhu, was recognized as an artist in Bombay—though both came from clay-modeling families. For an exhaustive range of JJ alumni profiles, see Bahulkar et al., Encyclopaedia Visual Art of Maharashtra.

- 32“J. J. School of Art,” Times of India, January 24, 1955. In 1954, caste-based reservations in higher education were introduced to address historical disadvantages faced by Scheduled Castes (SCs), who were also categorized as “Backward Classes.”

- 33See Kapilacharya, “Shiv Sena Speaks: An Official Statement,” ed. Bal K. Thackeray (Marmik Cartoon Weekly Office, 1967); and Sudha Gogate, The Emergence of Regionalism in Mumbai: History of the Shiv Sena (Popular Prakashan, 2014); and Gyan Prakash, Mumbai Fables(Princeton University Press, 2010).

- 34Bombay had a long, effective, and checkered history of labor politics associated with its textile mills from the 1920s through the Great Textile Mill Strike in 1982. The 1982 strike was clamped down on by mill owners, who refused to accede to workers’ demands for higher wages, leading to the dismantling of both the mills and trade union politics. See Chandavarkar, “From Neighborhood to Nation,” 28–77.

- 35Chandavarkar, “From Neighborhood to Nation,” 8. See also Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratinav Anil, India’s First Dictatorship: The Emergency, 1975–1977 (Oxford University Press, 2021), 446; and H. van Wersch, The Bombay Textile Strike, 1982–83 (Oxford University Press, 1992).

- 36Raghubir Singh and V. S. Naipaul, Bombay: Gateway of India (Aperture, 1994), 9. In conversation with the controversial Trinidadian-born British writer of Indian

- 37Mia Fineman et al., Raghubir Singh: Modernism on the Ganges, exh. cat. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017), 21–29. Singh, who went back to the chromogenic printing process in his later career, had early access to color film because of his work for National Geographic and other international publications at a time when it was not available in India due to trade restrictions, and he was an early proponent of it when it was still largely looked down upon by documentary photographers. See also, Julian Stallabrass, “Knowledge, Nation and Colour in the Documentary Photography of Luigi Ghirri, Raghubir Singh and Susan Meiselas,” in Art and Knowledge after 1900: Interactions between Modern Art and Thought, ed. James Fox and Vid Simoniti (Manchester University Press, 2023), 21. In Max Kozloff, “An Interview with Raghubir Singh,” Asian Art 2, no. 4 (1989): 15, Singh shares that he was always “interested in the documentary aspect of color,” 15.

- 38This direct confrontation is ubiquitous in his Bombay work. See Singh and Naipaul, Bombay: Gateway of India, 6. In his interview with V. S. Naipaul, Singh mentions that his Bombay photographs look “straight into people. My other books don’t do that, as much as the Bombay work does. This work is direct. There is more confrontation and tension.”

- 39Kelkar, Story of the Sir J.J. School of Art, 30–31. See Jerry Pinto, Citizen Gallery: The Gandhys of Chemould and the Birth of Modern Art in Bombay (Speaking Tiger, 2022), 208, for a cited reference of art historian Jyotindra Jain’s disillusionment and frustration with the colonial art lessons that he was exposed to as a student at JJ in the late 1960s. F. N. Souza, the polemical founder of the Progressives/ Progressive Artists Group (PAG), is quoted as being staunchly disapproving of what he believed to be the low quality of students and shows churned out by JJ and the Bombay Art Society. In 1984, he recalled that their art suffered from a crisis of imagination and a disconnect from the present, and that the radical foundation of the PAG at the turn of Independence was a reactionary move away from artistic orthodoxy of the human form. See Souza, “Progressive Artists Group,” Patriot Magazine, February 12, 1984; quoted in Yashodhara Dalmia, The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives (Oxford University Press, 2001), 42. See also Pralhad Anant Dhond, “Scheme to Shut Down the School of Art” [1968], trans. Sohnee Harshey, in Citragōṣṭa, 167–72, an article that first appeared in a 1968 issue of the Marathi periodical titled Roopa Bheda; and “J. J. art exhibition sub-standard,” Times of India, February 25, 1983. JJ’s website also notes several faculty and administrative vacancies; see “Members of Faculty,” Sir JJ School of Art, Mumbai website, https://www.sirjjschoolofart.in/departments/members-of-faculty.

- 40Nina Martyris, “JJ School hopes to find old spark with a little help from new friends,” Times of India, October 6, 2002; “Work on JJ school begins,” ibid., March 6, 2004; and Bella Jaisinghani, “JJ School of Art Syllabus set to change course,” ibid., September 25, 2009. For the most recent comprehensive but staggering list of “deficiencies” at JJ, see the All India Council for Technical Education, “Approval Process 2023–24 [. . .],” https://www.sirjjschoolofart.in/uploads/editor-images/AICTE%20Aproval%20Report%202023-2024.pdf.

- 41By 1994, JJ had implemented a 50 percent reservation of seats. See “Reservation of Seats,” Sir J. J. School of Art, Mumbai website, https://www.sirjjschoolofart.in/programmes-info/reservation-of-seats.

- 42Pallavi Smart, “Exhibition at Mumbai’s Sir JJ School of Art gives glimpse into evolution of art education in India,” Indian Express [Mumbai], March 11, 2025.

- 43Niraj Pandit, “JJ School of Art Models Get a Pay Hike of ₹200–500 after a Decade,” Hindustan Times, December 24, 2024.

- 44See Thomas Blom Hansen, Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay (Princeton University Press, 2001). In 1992, a year after Singh took the image at JJ, the city was engulfed in anti-Muslim riots in response to the demolition of the Babri Masjid, a mosque in Ayodhya. These attacks were led by vast sections of the lower caste and poor, with the active engineering of upper-caste and middle-class members of the Shiv Sena, enmeshed with powerful political and business interests in the city. Between 1995 and 1996, Bombay was renamed “Mumbai” to symbolize a reclamation of the city by the local Maharashtrian population. See also Goswami, Producing India, 12. In late 2023, JJ was granted “deemed university status,” a move welcomed by alumni as it ensured the institution would offer a “world-class education,” including adequate student residential accommodation. Others have stated that the proposed fee hikes associated with this new status will deter economically disadvantaged individuals from applying. See H. T. Correspondent, “Sir J J School of Art and Architecture to Become Deemed University,” Hindustan Times, June 29, 2023.