At what moment did artists in Korea show work that was considered experimental, underground, and contemporary? How are the first Korean Happenings, from the late 1960s, seen from today’s perspective? These questions were addressed by Kim Mikyung at a C-MAP presentation at The Museum of Modern Art in April 2014. Her talk, published below, surveys the major figures in Korea’s underground art scene from the postwar period to the present and leaves us with many questions to ponder. Can we conclude that experimental art need not be a form of social and political criticism, but that it is usually fostered in an atmosphere of rebellion against unyielding power structures?

I. Progression

When did “experimental art” emerge and spread in Korea? Why did I specifically use the general term “experimental art” in my doctoral dissertation? Why was this art form alienated from and treated harshly by the inner circle of the Korean art world? How were Korean artists able to foster their own distinct identity and find a solidly grounded attitude and way of thinking despite external influences from Western and Japanese avant-garde artists, a fortiori under Korea’s military regime?

“Experimental art” was never truly considered a component of mainstream art, nor was it perceived to bear any real historical significance until 1999, when I presented my doctoral dissertation, “Experimental Art and Society in Korea in the 1960s and 1970s,”1Kim Mikyung, “Experimental Art and Society in Korea in the 1960s and 1970s,” PhD dissertation, Ewha Women’s University, Seoul, 2000. which provided the foundation for the exhibitions Korean Contemporary Art from the Mid-1960s to the Mid-1970s: A Decade of Transition and Dynamics2Kim Mikyung, “In Search of a New Starting Point for Korean Contemporary Art,” in Korean Contemporary Art from the Mid-1960s to the Mid-1970s: A Decade of Transition and Dynamics (Seoul: National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2001), 29–50. Exhibition catalogue. in 2001 and Performance Art of Korea 1967–20073Kim Mikyung, “Performance Art of Korea 1960–70,” in Performance Art of Korea 1967–2007 (Seoul: National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007),14–37. in 2007, both held at Korea’s National Museum of Contemporary Art.

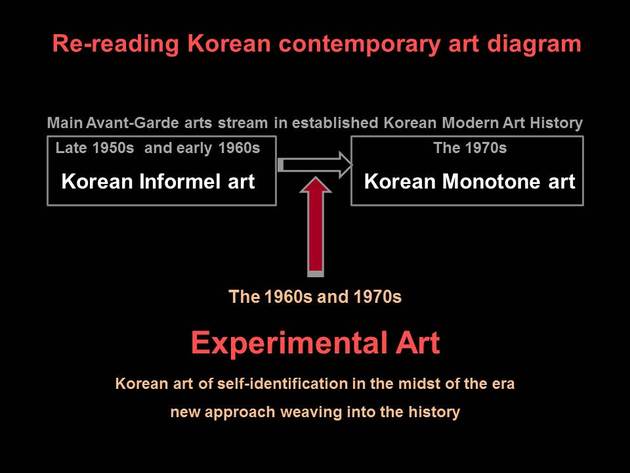

After the Korean War, a strong avant-garde movement in Seoul offered momentum toward nurturing experimental art in Korea. The artists wended their way beyond the conventional meanings and parameters of acceptance deeply ingrained in the Korean art world with their specific conception of time and space. It is widely agreed in Korea that the Korean Informel movement emerged in the 1950s and that what I would like to term “Korean Monotone Art”4I used the term “Monotone Painting” in the PhD dissertation in 2000. The term went through a further change and became “Monotone Art” (Dansaekjo Yesool). However, the name of the movement connotes not only “mono” (singular) and “chrome” (color), but also “tone” or “tonality” as it is understood in music. The term “tone,” then, reflects the intention of the Korean artists in question, which points beyond the typical signification of “painting.” This intention, as I have proposed, is reflected through these artists’ use of material as well as their physical properties, which in turn encompass their subjective rendition of time and space. Meanwhile ,the term “Monochrome Painting” (Dansaekhwa) popularized by the art critic Yun Jin Sup, was used for the title of the 2012 exhibition at the Korean National Museum of Contemporary Art (Dansaekwha: Korean Monochrome Painting). It is unfortunate that, in the terms “dansaek” (monochrome) and “hwa” (painting), the question of materiality is not sufficiently addressed. Strictly speaking, the artists in question do not subscribe only to the realm of color and picture, but it is precisely in subsuming the question of materiality and spatio-temporality that monotone art aspires to move beyond the traditional notion of painting and the assumption of color. began to take hold in the 1970s. The ascendancy of these two art forms resulted in the marginalization of certain types of experimental art, including performance art. Nevertheless, Korean experimental art succeeded in laying the foundations for self-identification and expression during this era, which were viciously dampened by military repression and extreme imbalance in wealth distribution, social upheaval, and economic strife.

II. Rereading “Experimental Art” in the 1960s and 1970s in Korea

The new experimental movements were never fully embraced or appreciated for what they were; experimental artists, because of their involvement in many social issues, constantly had challenged the repressive nature of government control.

II. 1. Rereading the Overlooked Pioneers

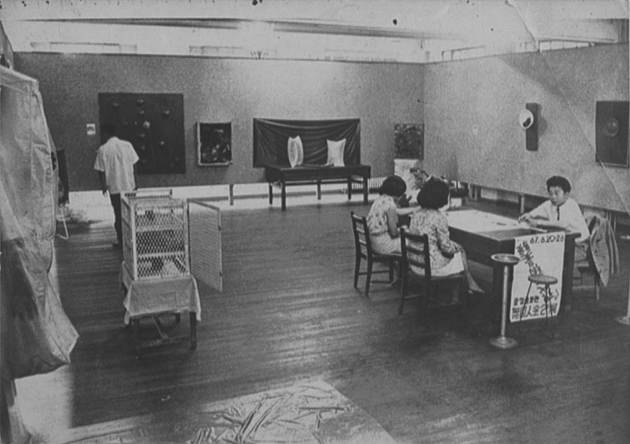

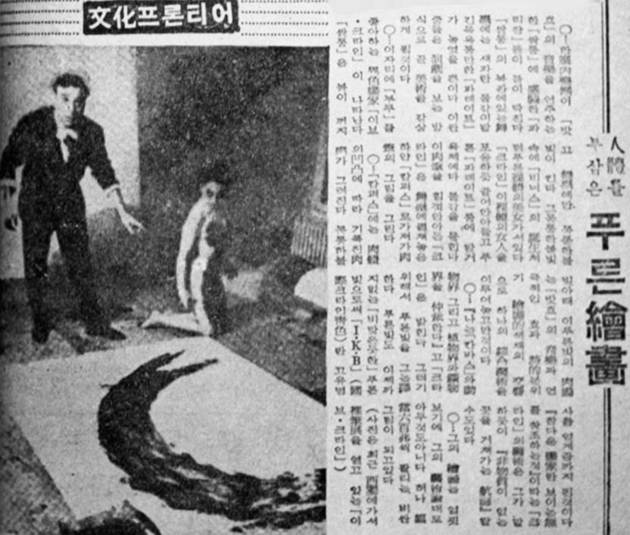

The First Exhibition of Objets of the group Mu (Zero), 1967

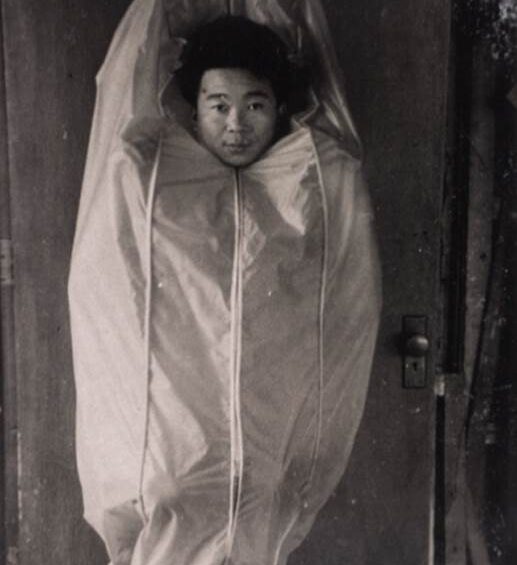

The very first exhibition of “objets” in Korea was held by the group Mu on June 20, 1967. The group neither sought to draw the public’s attention nor were its members regarded as pioneers at the time of their founding as the term “exhibition” predominantly stood for painting exhibitions. They were complete novices in the Korean art world, fresh out of university. Nevertheless, the artist Lee Tae Hyun alluded to the military government’s restriction through his use of objects such as a gas mask and a military backpack. Meanwhile Choi Bung Hyun’s evoking of a dead body and his self-confinement in a garment bag to suggest the death of his own freedom, which seemed like being dressed in a straitjacket, indisputably symbolized the restriction and death of society. I think these artists were regarded as rookies, and practically speaking “nobodies.” This meant that they passed largely unnoticed. I also feel that these young artists, practically unknown at the time, proceeded without much government intervention, at least in the beginning of their careers. This was largely due to the general public’s indifference and the casual attitude of government officials, who often looked upon Mu’s work as practical jokes or youthful mischief. Later, however, members of the group did have to endure physical attacks and arrests, as did many other experimental artists of that period.

Six months later the Chungnyun jakka yeunlipjun (Exhibition of the Young Artists’ Union) was held. Individual and group performances by members of Mu and Shin Jun and the street demonstration held at the time of this event are the first of their kind to be documented in Korean art history. Despite the significance of their initiatives, however, they had gone practically unnoticed until my PhD dissertation of 2000.

Vinyl Tube Spouting Out Watercolor, 1967

Vinyl Tube Spouting Out Watercolor was first performed by Kang Kuk Jin on the opening day of the exhibition. While there have been studies of the first group Happening in Korea, Kang’s performance, staged three days earlier, was relatively overlooked by the public and the critics. It consisted of a large vinyl tube, which was suspended from the ceiling and loosely held upright by a rigid circle-shaped base at each end. Suspended inside the large tube were smaller vinyl tubes filled with watercolor. The performer’s only action was to remove one of the bases, which triggered a spontaneous splattering of colors. The work became a sort of three-dimensional painting, untamed in its joyous release.

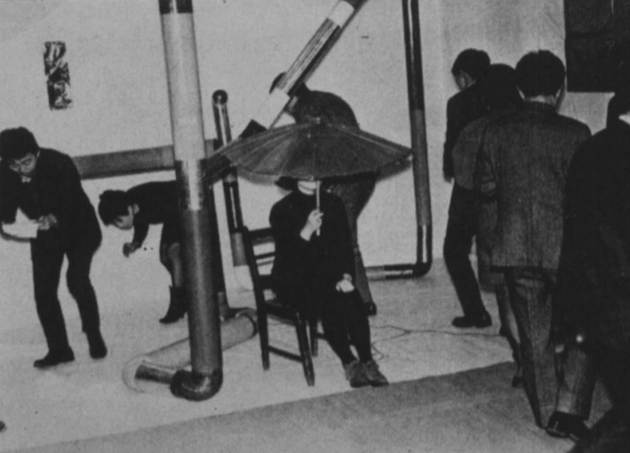

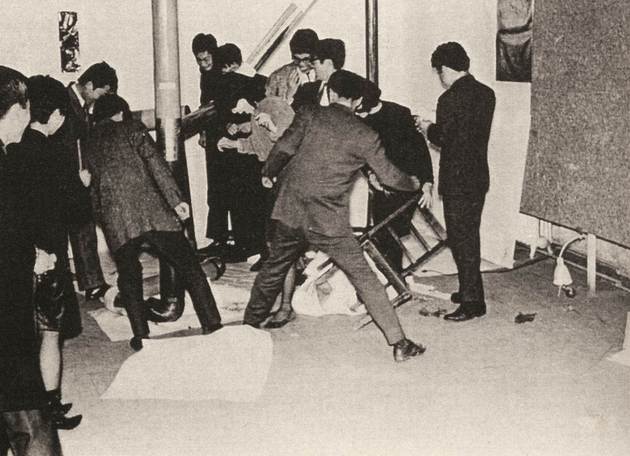

The First Group Happening, Happening with Vinyl Umbrella and Candles, 1967

It was also in the winter of 1967 that some young Korean artists staged Happening with Vinyl Umbrella and Candles, the very first group Happening to be performed in Korea. It was not until much later that it came to be understood by the public as a historic milestone.

Even though it had been nine years since Yves Klein had presented Le Vide (The Void) and seven years since he had staged the performance Les anthrophométries de l’epoque bleu (Anthropometries of the Blue Period) in Paris, the concept of the Happening was still in its infancy in Korea and being tested by only a very few avant-garde artists. In Happening with Vinyl Umbrella and Candles, members of the group Mu and Shin Jun (New Exhibition) moved slowly around in circles. The artist Kim Young Ja, a member of Mu, sat in the center while the rest of the participants sang “Bird Bird Blue Bird,” a well-known folk song attributed to Jun Bong Joon, who led the Donghak Peasants Revolution in 1894.5Donghak(東學) means “Eastern Learning.” The Donghak Peasant Revolution in Korea was the endpoint of a series of Japanese coups in Korea that brought the Joseon dynasty to an end. In a transitional economy, opened to uncontrolled foreign trade, Korean yangban scholars and peasants attempted to stop further Japanese incursions into Korea and maintain independence. In the chaos that ensued, Japan invaded, installed puppet administrators, and began Japanese colonial rule that lasted until the unconditional surrender of the Japanese at the end of World War II in 1945. The question of whether the Donghak Revolution was instigated by Japan to create the circumstances for invasion and then became a true mass peasant uprising, or whether the rebellion was an intellectually spearheaded revolt that, after gaining traction among the peasant class, was exploited by Japan as a pretext for invasion, is a subject of constant study and debate by Korean historians. Kim held an open vinyl umbrella while seated between two upright elements in Choi Bung Hyun’s installation Stovepipe. In the 1960s and 1970s, this type of stovepipe, a feature of the popular briquette stove, was standard heating equipment for the humble class. Choi used it in the installation to create a scene with a familiar folk ambience.

The circling performers decorated the top of Kim’s umbrella with small lit candles, which they then used to poke through the vinyl fabric. This was followed by another circular movement that culminated in a sudden but staged collective attack on Kim. During the faked scuffle, the candles were extinguished and the umbrella was torn apart. The choreographer of the performance, Oh Kwang Soo, explained later that the umbrella is a symbol of the nuclear explosion at Hiroshima, the candles represent pure human spirit, and the conjunction of the song and the performers’ actions represent chance of the kind presented in Dada performances.

It seems clear that the writers and artists who carried out this Happening believed that they were engaging in a form of artistic expression that resembled the avant-garde art of the West: a way of consolidating their legitimacy in Korean avant-gardism, perhaps ensuring the legitimacy of the avant-garde of Korea. However, I would argue that the juxtaposition of the song “Bird Bird Blue Bird” with the action involving the umbrella and candles must be compared to Dadaist concerns such as contingency and chance. It reveals the participants’ revolutionary conscience and their deep-seated will to resist governmental repression, which for so long had forced them down. In addition to Homi Bhaba’s relevant observation that when the colonized imitate their colonizers, the result is “almost the same [as the model], but not quite,”6Bhaba, Homi K, Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 86. what stands out is the inseparability of art and society that was unique to Korean circumstances at the time.

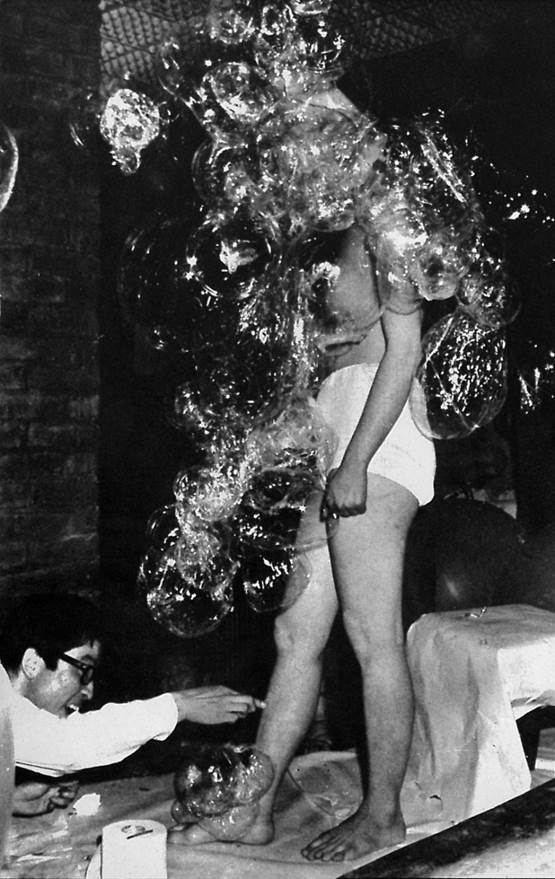

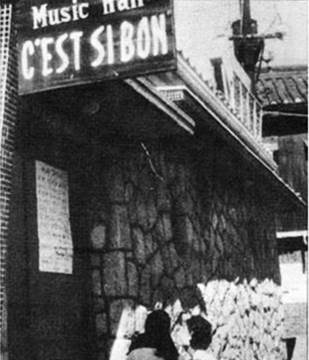

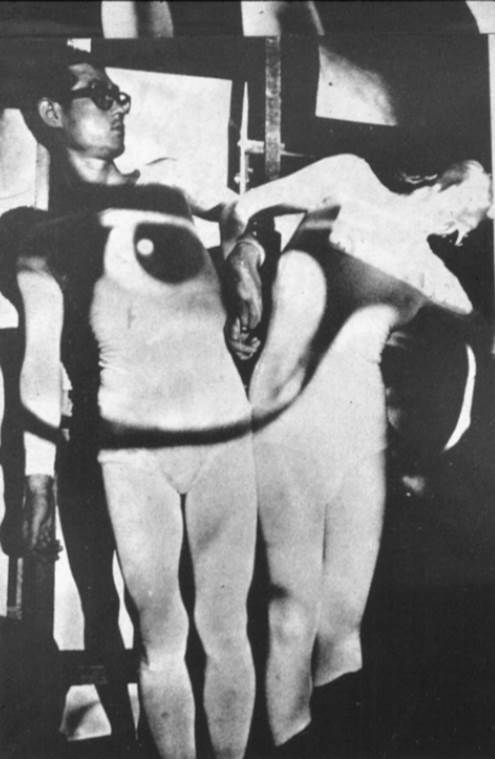

The First Semi-nude Happening, Transparent Balloon and Nude Happening, 1968

The first nude Happening in Korea was performed in 1968 by Jung Kang Ja at the C’est si bon music hall, which was widely known as a venue for young folk singers. Dressed only in underpants, Jung stepped onto the darkened stage accompanied by a recorded track of rhythmic percussion. She sat down, and several artists inflated small transparent balloons with adhesive surfaces and then stuck them on her body. When she stood up, the artists (Kang Kuk Jin and Shim Sun Hee, Jung Chan Seung, and Kim Mun Ja) and a few spectators sprang at her, slapping her and bursting the balloons. Here, the subject was the destruction of the stereotypical concept of beauty, embodied by a fragile female figure ornamented with transparent balloons. In the aftermath of the violent splattering of the objects covering her body, she is in the midst of brutal exposure, and becomes the symbol of the destruction of the stereotype. It seems strange to me that the Happening was not interpreted in this way even in later years, when feminism first arose in social debates during the 1990s. The ideas of feminism and feminist art seemed to operate under the assumption of Western archetypes.

Staged during a period when feminism was hardly recognized in Korea, Transparent Balloon and Nude Happening was decidedly Korea’s first Happening in which body, performance, light, music, performer, and audience were brought together in the context of feminism. Here it is important to note that the conceptual stance of Jung Chan Seung differs from that of Yves Klein, who used the female body as an aesthetic instrument directed by the male artist, notwithstanding the idea of Jung’s plan, which can be summed up by her statement, “Let’s do it like Klein.”7Kim Mikyung’s interview with Jung Kang Ja and Choi Bung Hyun on April 9, 1996. They testified that Jung Chan Seung said, “Let’s do it like Klein” in the preparation stage of the Happening. Kim Mikyung, Experimental Art in Korea (Seoul: Sigongsa, 2003), 92.

It turns out that the reception of Jung’s work resembles that of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece of 1964. Cut Piece has been interpreted in a variety of ways: it has been considered as an exploration of sadism and masochism, of violence and victimization, and it has also been discussed in terms of feminist discourse on the female body and the male gaze.

Untitled, Performed in the Name of Environmental Art, 1969

Before they officially banded together in 1970, the 4th Group staged an untitled performance in the name of environmental art. Dressed in white bodysuits, the artists served as moving projection screens. Countless images, including the pupil of a huge eye, a girl’s face, and a desert landscape, were projected onto the human screens as well as onto the walls, ceiling, and floor. They countered the received notion that the screen or canvas should be fixed to the wall.

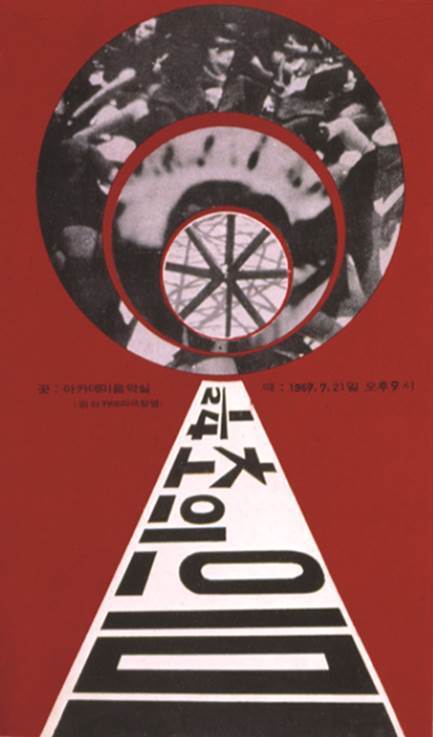

The Backstory of the First Experimental Film, The Meaning of One Twenty-fourth of a Second, 1969

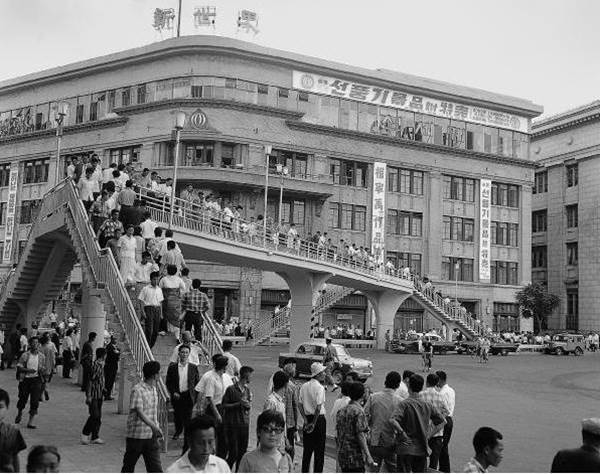

On July 21, 1969, the day of the satellite broadcast of the first lunar landing, Korea’s first experimental movie, The Meaning of One Twenty-fourth of a Second, was released at Seoul Academy music hall. Made by Choi Won-Young (director), Jung Chan Seung, Kim Ku Lim, Jung Kang Ja, and Ban Dae Gyu (cameraman), the film, which is silent, was intended to express the existential conditions of modern life. It was shot in the rapidly developing city of Seoul: on the streets and in other public places. The shifting scenes flow at varying speeds in order to convey impressions of tediousness, fast-paced life, simple happiness, and cruelty.

The artists thoughtfully aimed to produce Total Art, in which body, space, and film are fused together. Their efforts were met with sneers by the art world.

Shockingly, this work—Korea’s very first avant-garde film—lay in obscurity for almost thirty years in the archives of the Osaka Art Center in Japan, while Kim Ku Lim was in exile there.

At present, Kim Ku Lim holds the copyright to the film, despite the fact that there are three other artists involved in the process. When I interviewed Choi Won Young and Jung Kang Ja in 2010, they insisted that the film was edited by splicing tapes after shooting, using only the positive film. Later on, the film was reedited and altered by Kim Ku Lim, the last participant to join the filmmakers’ team in 1968. When originally shown, the work was played at a far faster speed, its images distorted by separate projections that were partially obstructed by objects including cubes and triangular pyramids. Moving human screens and noisy music were also integral parts of the initial screening.

II. 2. The Spirit of Resistance under the Military Regime in Korea

As the 1960s generation was becoming increasingly allured by potential economic growth, the Korean government resorted to seeking economic help from outside, mainly from Japan. The result brought about the bilateral summit in 1964. Citizens of Korea were enraged and subsequently organized anti-Japan demonstrations, which took place across the nation. The reason for their anger is easy to understand: from 1910 to 1945 unthinkable acts of brutality had been committed in Korea by the Japanese colonial government. Now, while Japan was thriving after a relentless postwar reconstruction effort that culminated in the country’s hosting the Olympic Games in 1964, much of Korea was still struggling at a subsistence level.

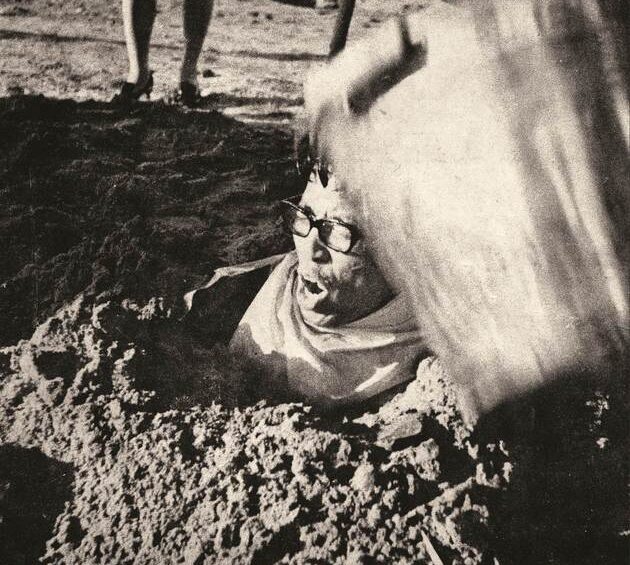

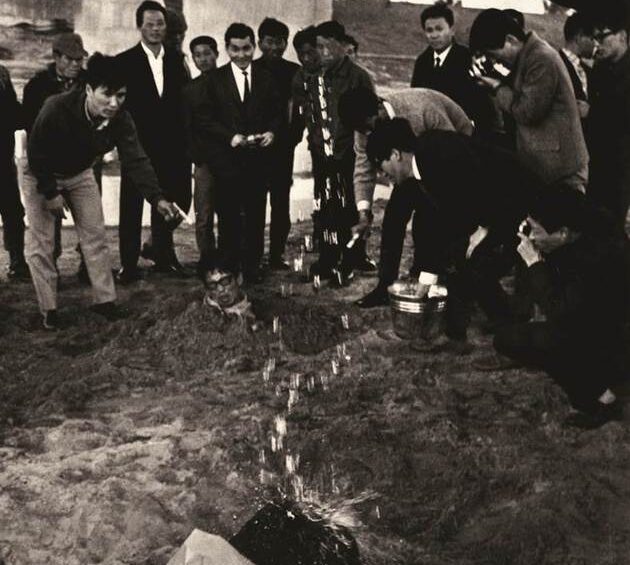

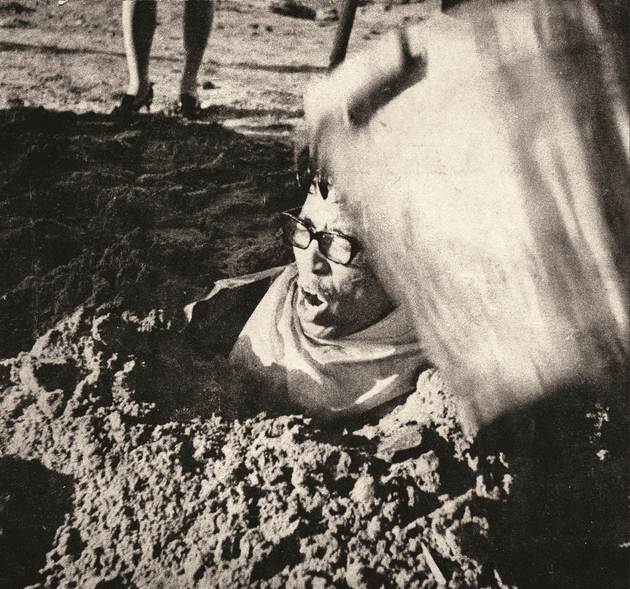

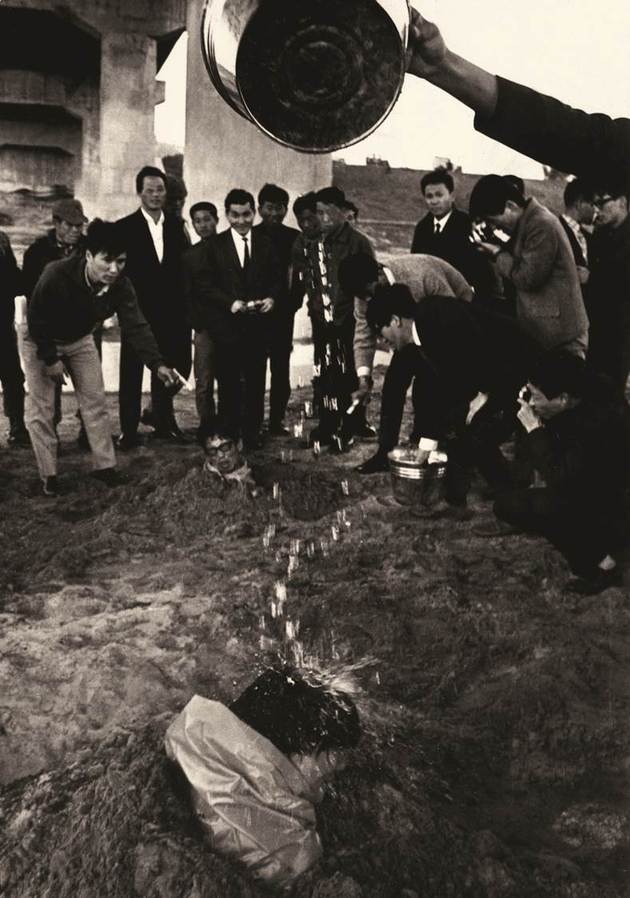

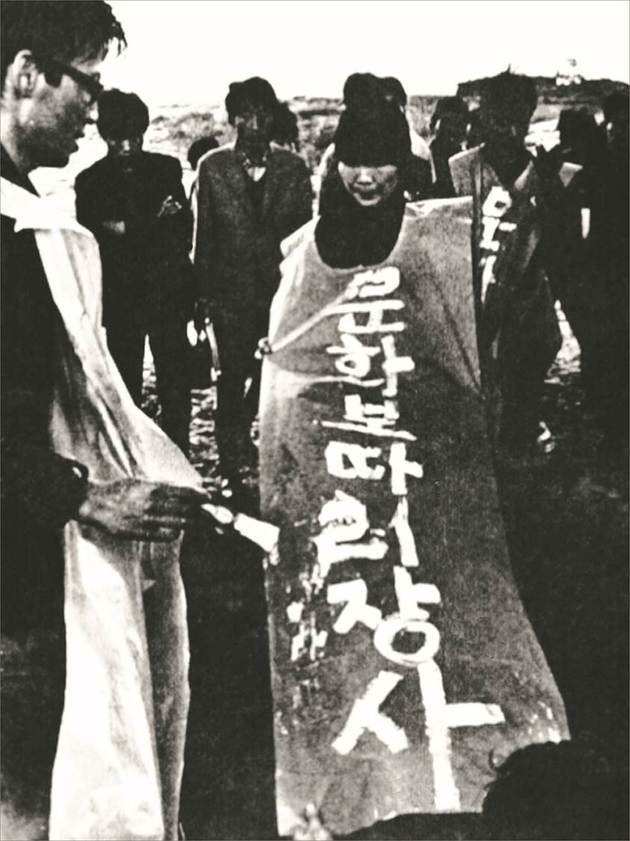

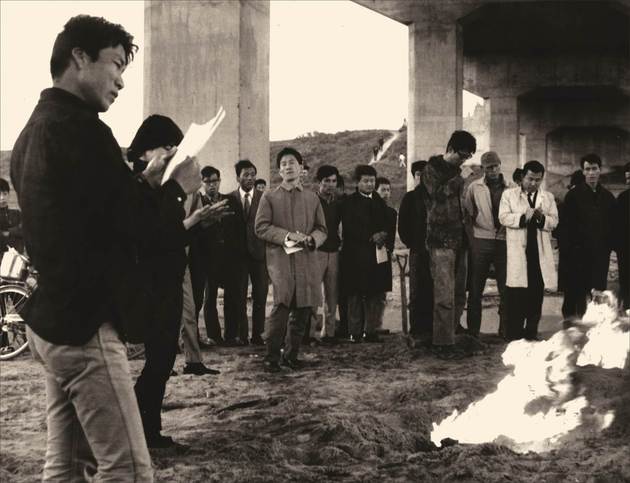

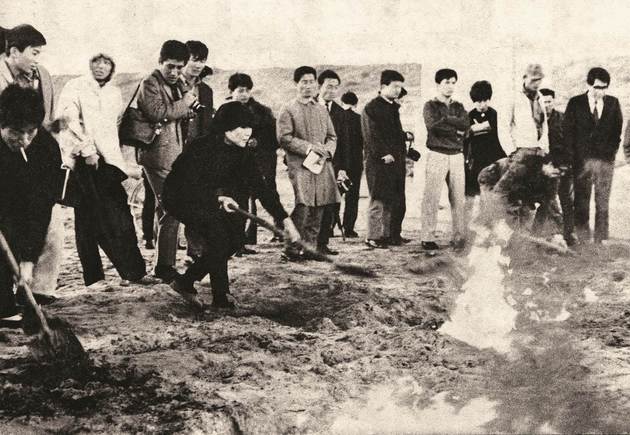

Murder at the Han Riverside, 1968

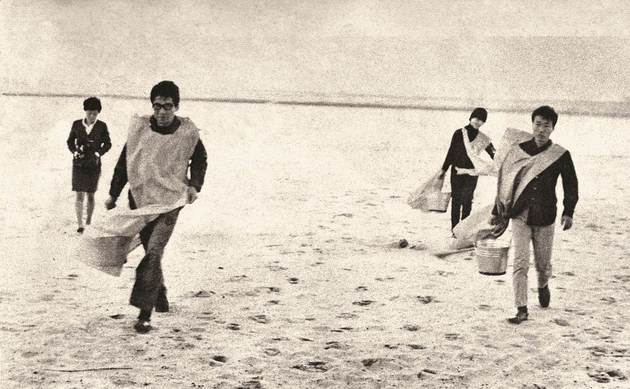

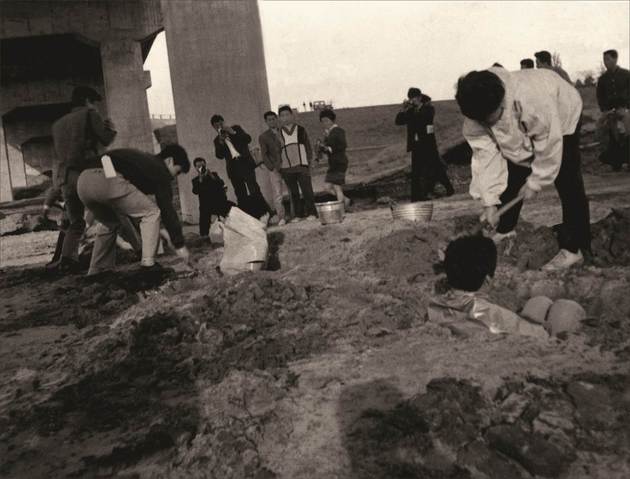

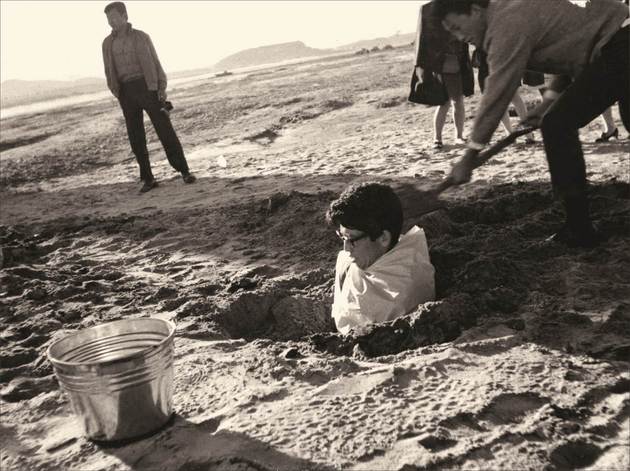

Less than five months after performing in Transparent Balloon and Nude Happening, Jung Chan Seung, Kang Kuk Jin, and Jung Kang Ja dug deep holes under the second bridge of Seoul’s Han River. Then they entered the holes and had spectators pour water over them. After climbing out of the holes, the artists wrote critical phrases on long vinyl tabards: “cultural swindler” (pseudo-artist), “cultural blind” (culture phobia), “cultural shirker” (idealist), “illicit fortune maker” (pretended great master), “cultural peddler” (political artist), and “cultural acrobat” (artist jumping on the bandwagon). Finally they screamed and shouted each phrase and proceeded to burn the tabards, an act of destruction, urging disenchantment from the depravation of the ancien régime.

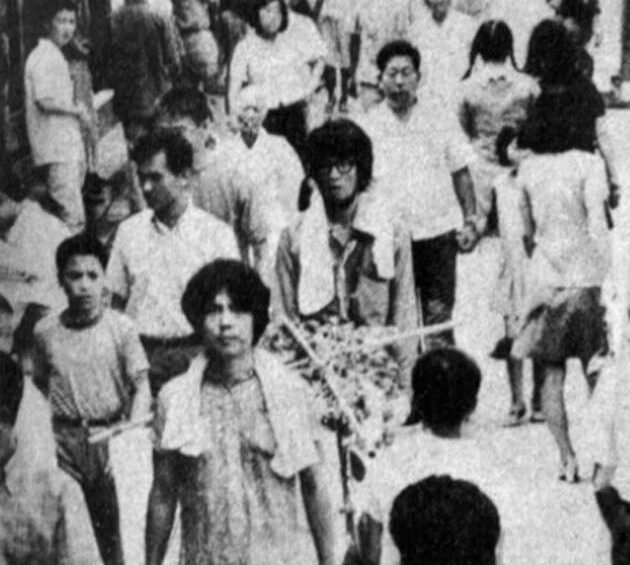

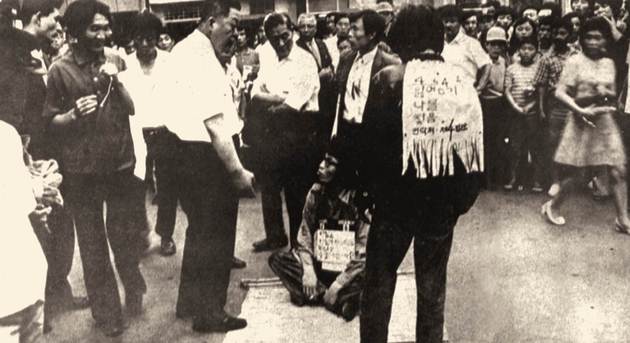

Pantomime on the Street, 1970

Two years later Jung Chan Seung and Go Ho suggested that the sincerity of human relationships be regained in modern society to lessen the prevailing sense of alienation. Bang Tae Soo, the representative of the theater group Ee, Jeo, Tto (Hmm, Well, And) can be seen laughing in the photo as a passerby ridicules their act. In a scene that followed, Jung Chan Seung gets locked in a shop behind a display window, crying out from thirst and hunger. All of Go Ho’s efforts to deliver bread and wine to his locked-up friend inevitably failed because of the obstruction of the shop window. A passerby, refusing to remain a mere spectator, entered through the back door of the building and compassionately handed Jung a morsel of bread and some wine. Immediately afterward, a policeman arrested Jung Chan Seung and Go Ho. No one realized that this was a piece of street art. They were later arrested and investigated by the police.

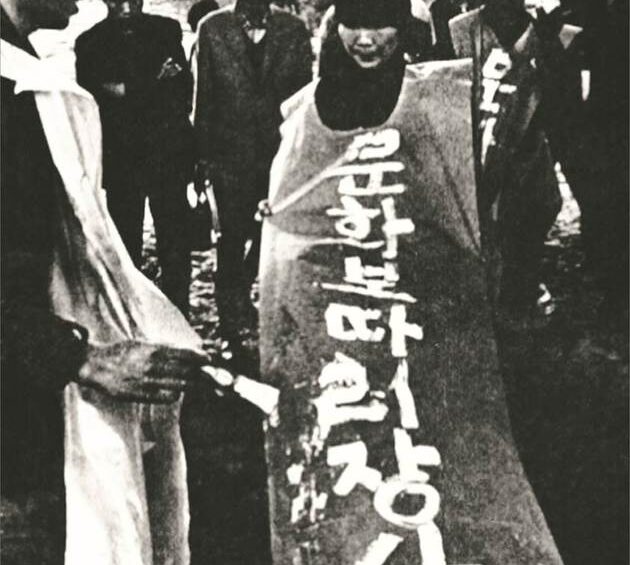

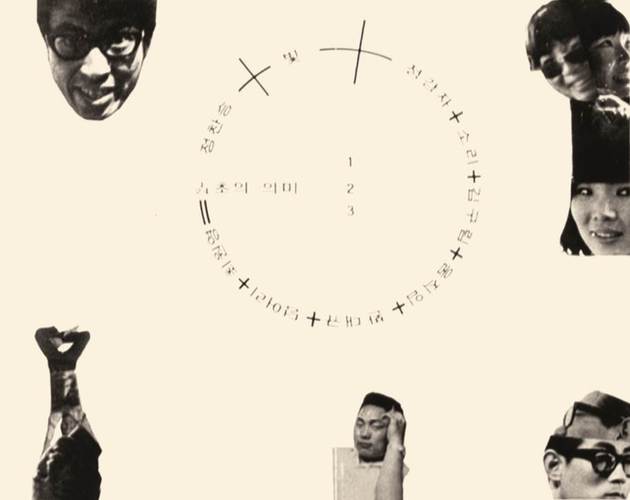

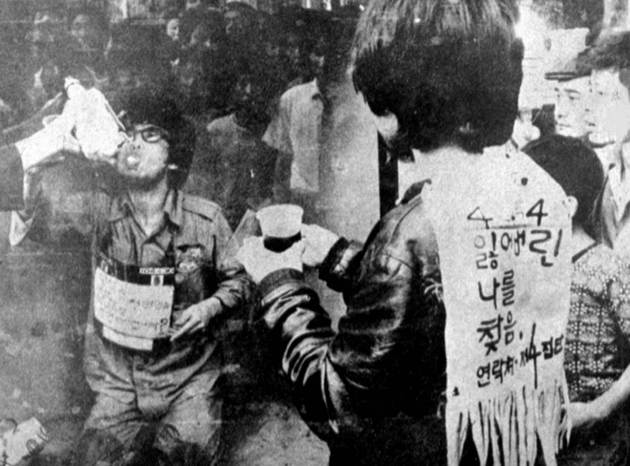

Funeral Ceremony of the Established Art and Culture, 1970

The 4th Group formed on June 20, 1970, the twenty-fifth anniversary of independence of the Republic of Korea. Nearly all of the group’s members were antiestablishment activists and experimental artists. Before being forced to break up less than a year later, using the slogan Muche (無体, zero state, non-constitution) and the symbol of the white flag, they decried military repression and called for change that would integrate all aspects of society (economic, cultural, and social) under the banner of art. The group, led by Kim Ku Lim and Bang Tae Soo, both before and after its dissolution, resisted government pressure and criticized the negativity posed by the reality of Seoul. Bang was also a leader of the underground theater group Ee, Jeo, Tto, named after a satirical phrase that grew out of the prohibition against uttering a word on the subject of social control, where the only utterable words under the extreme scrutiny of the government were “Hmm (Ee), Well (Jeo), and And (Tto).” Kim Ku Lim went into exile in Japan after the 4th Group was forced to disband. This happened after they carried out the project named Funeral Ceremony of the Established Art and Culture, which members say was a critique of conventional art and culture in Korea, not as a demonstration against the government.

On Gwangbokjeol (National Liberation Day) of 1970, the members of the 4th Group gathered in Sajik Public Park, where they read aloud their decree calling for the independence of Korean culture. Then they marched down the main street nearby. Kim Ku Lim led the procession. He and Jung Kang Ja each waved the Korean national flag and the 4th Group’s white flag, symbolizing purity, sunlight, the universe, traditional white Korean clothes, and spirituality. Behind them, Jung Chan Seung and Son Il Kwang carried a coffin decorated with flowers and the Korean national flag.

Starting from Sajik Public Park, the march was planned to proceed to the Gwanghwamun Gate, then over the first Han River Bridge, and finally along the white sands of the riverbank, where the funeral would be performed. However, as many feared, the marchers were arrested near the Gwanghwamun Gate for violating traffic laws, and the short-lived funeral came to an abrupt end.

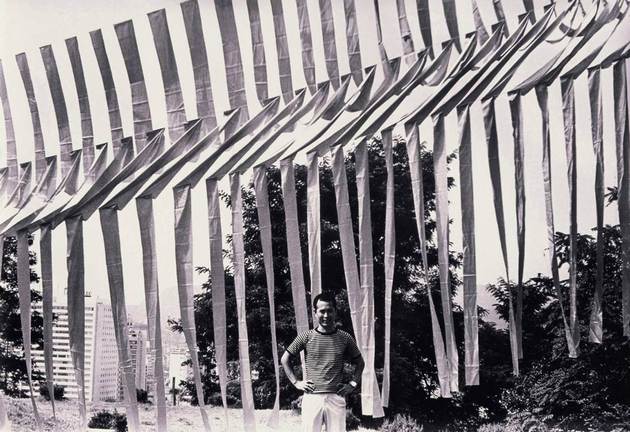

Along with the Wind, Non-sculpture in Space

Among the thoughts of the Chinese philosopher Lao-Tzu are the following: “Things are not as they seem,” and “Being, in coming into being, is produced by nonbeing.” It is precisely when Lee Seung Taek’s long strips of cloth were set in free motion in the natural wind that the “coming into being” of the strips happened. The artist calls the works “non-sculpture.” The fabric and the wind create continuously fluctuating shapes that are constantly “in the making,” forever “coming into being.” I recall the scene of traditional Korean fish banners at an annual ceremony alongside rural altars where fishermen and farmers invoke spirits whom they implore to grant them an abundance of fish and crop yields in the coming year. In this event we can see the flags or cloth strips flutter.

Ⅲ. Conclusion

The level of maturity of a country’s artistic culture and cultural consciousness is often measured by its freedom of expression. If judged by such a standard, Korea in the 1960s and 1970s would definitely score low. Before the advent of democratic freedom, the country’s atmosphere was grim. Artists who responded critically to government proposals or actions were arrested and often tortured harshly.

It is commonly thought that the main culprit in curtailing underground experimental art in Korea was the lack of public understanding as well as cohesive power in artists’ communities. But the most devastating blow to be dealt was the combination of government repression and the society’s fundamental lack of support and negative attitudes.

The willingness to accept the coexistence of different kinds of art is what brings us to cultural maturity. It is the source of a formidable inner power to be able to understand that a certain sort of art is “art for art’s sake” and that another sort of art engaged with social issues. Korea, far from such a level of maturity, was home to many underground groups studying and deliberating in isolation. Their experimental art practices, rooted in resistance against certain social and political forces, started to fade out in the second half of the 1970s, when the military government’s proclamation of martial law clamped down still further on human rights and freedom. This sequence of events ultimately drove Korea’s divergent forms of experimental art into the camp of Conceptual art. Despite all these adversities, experimental artists were able to show humor, sanity, and, above all, their will for freedom.

- 1Kim Mikyung, “Experimental Art and Society in Korea in the 1960s and 1970s,” PhD dissertation, Ewha Women’s University, Seoul, 2000.

- 2Kim Mikyung, “In Search of a New Starting Point for Korean Contemporary Art,” in Korean Contemporary Art from the Mid-1960s to the Mid-1970s: A Decade of Transition and Dynamics (Seoul: National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2001), 29–50. Exhibition catalogue.

- 3Kim Mikyung, “Performance Art of Korea 1960–70,” in Performance Art of Korea 1967–2007 (Seoul: National Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007),14–37.

- 4I used the term “Monotone Painting” in the PhD dissertation in 2000. The term went through a further change and became “Monotone Art” (Dansaekjo Yesool). However, the name of the movement connotes not only “mono” (singular) and “chrome” (color), but also “tone” or “tonality” as it is understood in music. The term “tone,” then, reflects the intention of the Korean artists in question, which points beyond the typical signification of “painting.” This intention, as I have proposed, is reflected through these artists’ use of material as well as their physical properties, which in turn encompass their subjective rendition of time and space. Meanwhile ,the term “Monochrome Painting” (Dansaekhwa) popularized by the art critic Yun Jin Sup, was used for the title of the 2012 exhibition at the Korean National Museum of Contemporary Art (Dansaekwha: Korean Monochrome Painting). It is unfortunate that, in the terms “dansaek” (monochrome) and “hwa” (painting), the question of materiality is not sufficiently addressed. Strictly speaking, the artists in question do not subscribe only to the realm of color and picture, but it is precisely in subsuming the question of materiality and spatio-temporality that monotone art aspires to move beyond the traditional notion of painting and the assumption of color.

- 5Donghak(東學) means “Eastern Learning.” The Donghak Peasant Revolution in Korea was the endpoint of a series of Japanese coups in Korea that brought the Joseon dynasty to an end. In a transitional economy, opened to uncontrolled foreign trade, Korean yangban scholars and peasants attempted to stop further Japanese incursions into Korea and maintain independence. In the chaos that ensued, Japan invaded, installed puppet administrators, and began Japanese colonial rule that lasted until the unconditional surrender of the Japanese at the end of World War II in 1945. The question of whether the Donghak Revolution was instigated by Japan to create the circumstances for invasion and then became a true mass peasant uprising, or whether the rebellion was an intellectually spearheaded revolt that, after gaining traction among the peasant class, was exploited by Japan as a pretext for invasion, is a subject of constant study and debate by Korean historians.

- 6Bhaba, Homi K, Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 86.

- 7Kim Mikyung’s interview with Jung Kang Ja and Choi Bung Hyun on April 9, 1996. They testified that Jung Chan Seung said, “Let’s do it like Klein” in the preparation stage of the Happening. Kim Mikyung, Experimental Art in Korea (Seoul: Sigongsa, 2003), 92.