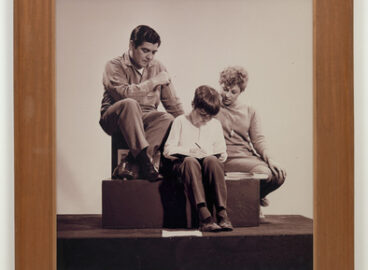

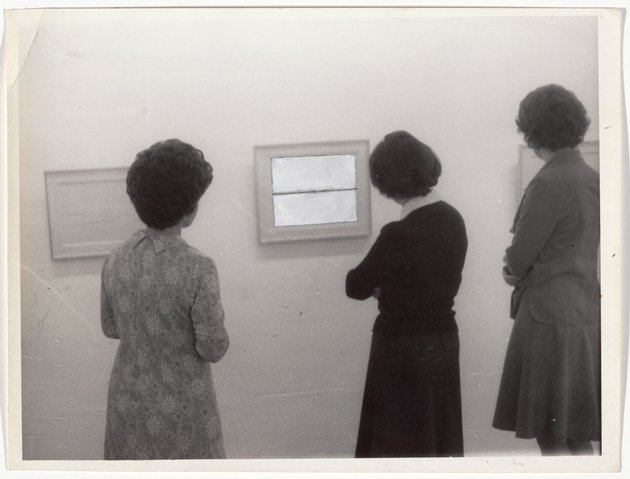

In 1959, the year he founded Gorgona with his friends and colleagues, Josip Vaništa staged a solo exhibition in Zagreb of his drawings from the 1950s. A black-and-white photograph commemorates the occasion; it shows three framed works on the wall, studied by three female visitors. The drawing on the left suggests the moody, delicate, somewhat abstract graphite drawings that the artist produced at the time—a near-abstract landscape reduced to little more than a horizon line, while the work on the right remains concealed by one of the attentive onlookers. The main focus of the women’s studied attention is the drawing in the center of the photograph, and yet we no longer can make out the details of the original work. For in 1965, six years after the picture was taken, the artist made an important change to the photographic print: he covered the central drawing on the wall with a thin layer of white paint and bisected it horizontally with a ruler-drawn black line. Formally not impossibly far from the abstracted landscapes of his other drawings from the 1950s, this new, fully abstract composition is nonetheless clearly a distinct alteration, a hand-painted addition to and conceptual leap from the photographically documented drawings of the 1950s. Instead of trying to suggest a trompe-l’oeil replacement of one work by another, the addition to the photo is clearly an intervention. It performs a different operation, one more important to the understanding of Vaništa’s development at this crucial moment, by linking visually and conceptually two distinct bodies of work and marking the leap his work took in the years between the original photograph and the edited version. Vaništa himself remarks on this moment: “The line appears at the very beginning of my work, on the first drawings and paintings. It appeared in its most radical form between 1962 and 1964, as a silver line on a white background or a black line on a gray background. It was shown at an exhibition reduced to only the typed description, ‘A silver line on a white background, height 3 cm, length 180 cm, canvas size 140 x 180 cm,’ dematerialized and developed into a concept. This was in about 1964.”

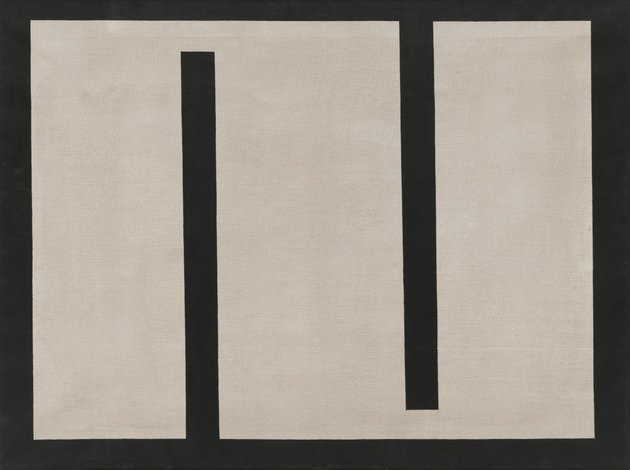

During the six years that had passed between the time Vaništa’s drawing exhibition was staged and the picture was taken, and the overpainting (coincidentally, the work’s title is Übermalung [Overpainting]) was added in 1965, several important conceptual maneuvers that are fortunately represented in MoMA’s collection had taken place: Vaništa and his cohort had founded the Gorgona group and had begun to publish and distribute the first eight issues of its magazine (also titled Gorgona); Vaništa’s colleague Julije Knifer had begun to make works dedicated to a single, repeating form—the meander, an S-shaped white form on black ground or black form on white ground—which he would continue to explore until the end of his life; and Vaništa had begun a series of works that all share a similarly simple, overriding compositional principle—a single horizontal line that bisects a monochrome background in the center of a rectangular landscape format. The intervention into the earlier photograph suggests—even insists—that Vaništa’s conceptual horizontal lines have their beginnings in the more conventional graphite landscapes of the mid-1950s, a point the artist also makes in a later comment: “Landscape, flatland, and geometrical plane, and finally line—the horizontal line. What was left out of a drawing was more important than what was put into it. It led to simplicity, to reduction, to emptiness. And then to silence.”

Simplicity, reduction, emptiness, silence. These are categories of abstraction, of leaving out, of the essence of the work. They lead to a number of works that all share the same formula: a single horizontal line centrally located on a rectangular plane, first in black ink on white paper, or in black paint on a white painted canvas, and later in graphite on a silver ground, or as a silver line on white. Several of the works that follow this principle are in MoMA’s possession: Untitled (1964), a collage of a thin silver tape glued onto a white sheet of board and mounted onto a larger sheet of paper; Übermalung, the overpainted photograph mentioned above; and finally, maybe most radically, La Description (1964), a sheet of A4 paper containing a typewritten text, a description narrating the elements: “A silver line on a white background, height 3 cm, length 180 cm, canvas size 140 x 180 cm.”

Translation, repetition, dematerialization. Collectively, these works transform a radical (albeit modernist) gesture of pictorial abstraction and change its purpose, meaning, and thrust. The painted photograph Übermalung still insists on the continuity between landscape and Vaništa’s single horizontal line, the latter a remnant of the former, wrought from it through processes of removal and reduction. The drawings, paintings, and collages, repetitions of the same or similar gesture of the horizontal line, establish a repertoire of variations. But the typewritten text transforms the exercise on a single line into its idea; the written description conjures a transformation from object to definition, from abstraction to concept, from material to immaterial. It is tempting to situate Vaništa’s horizontal lines within a field of similar conceptual trajectories and instruction-based artworks that occur around the same time in the West and elsewhere: they share characteristics with Roman Opalka’s Details (begun in 1965), Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), and Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art (1969).

They engage with the classificatory redundancies and basic semiological demonstrations of One and Three Chairs, for instance, and share Sol LeWitt’s belief in the mystical, rather than rational, basis of conceptual art. Maybe both these comparisons are too dependent on the need to understand Vaništa’s horizontal lines as important in the context of similar, contemporary practices. I am not speaking of meaning, but rather of their place in the continuous trajectory of the historical development of art. Yet possibly the most radical aspect of Vaništa’s work from the early 1960s—just as of that of his Gorgonian colleagues, most importantly Julije Knifer—is that they resist the entire notion of “development.” Like Knifer’s meanders since 1960, Vaništa’s horizontal lines become extensions of the same impulse, together constituting one continuous work, extending the same gesture from one object and element to the next, seemingly infinite, and never finished. Unlike LeWitt’s instructions, in which the works exist as concepts to be actualized with every execution, an iteration of the same, in Vaništa (and Knifer), each work is different from the previous one, but continues it, renews its thrust, and extends its line. Only Opalka’s Details, the slow, continuous unfolding of consecutive numbers as they are painted onto progressively more white monochrome ground, begun in 1965 and only concluded with the artist’s death in 2011, had a similarly epic and yet unchanging character. Is it a coincidence that Opalka had also begun his project in the East, in Poland? Opalka’s numbers, Knifer’s Meander, Vaništa’s horizontal line are each a single concept, made once, or made forever; each is unique, each is radical, each is part of an infinite line.

This text was originally printed in a catalogue published by The Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb (Muzej suvremene umjetnosti) on the occasion of an exhibition devoted to Josip Vaništa in 2013.