Image Courtesy: The British Library, EAP1262/1/3/2, https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP1262-1-3-2

Bombay cinema looms large over media and cinema studies in India even though the history of the Bombay film industry is more recent than the history of film culture in the Subcontinent. The Bombay film industry as we know it today consolidated during the 1950s in the wake of the massive political and economic restructuring that followed the Partition of British India into India and Pakistan. Much before erstwhile Bombay became the prime filmmaking hub of independent India, film marketing, spectatorship, and criticism were already thriving practices in late colonial India (Fig. 1).

The rich history of pre-Independence film culture in India, however, remains understudied, and this has a lot to do with the difficulties of tracing non-textual and ephemeral popular-cultural forms through predominantly textual institutional archives. Recent film-history studies have drawn attention to the limitations of relying on sparse and badly preserved film archives, and scholars have instead begun to draw on a patchwork of sources, leaning particularly into the vast “parallel archives of paper” across vernacular languages to write deeper and more connected histories of print and cinema publics in India.1See, for example, Debashree Mukherjee, Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020); and Manishita Dass, Outside the Lettered City: Cinema, Modernity, & the Public Sphere in Late Colonial India (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). Adding to this web of scholarship, I examine three early twentieth-century Urdu film magazines published during the 1930s—The Film Review, Film Star, and Filmistan—as gateways into early film culture in India.2Preserved and digitized by the Shabistan Film Archive, Bangalore, and the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme. It was during the 1930s that film culture took off in earnest in the Subcontinent as the decade heralded the rise of the “talkies,” which introduced sound and, therefore, spoken language to Indian cinema (see Fig. 1). The decade thus marks a crucial moment of transition not only in film history but also in the trajectory of Urdu in twentieth-century India, which had by then become the subject of a reactionary language politics led by literary elites that was shrinking the boundaries of the Urdu public. Circulating in this sociopolitical context, film magazines bring into focus how Urdu was instrumental in cohering regionally diffused early film production into a shared and mutually legible film culture, and cinema, in turn, widened conceptions of the twentieth-century Urdu public by animating modes of viewing, listening, and speaking that blurred binaries of “high” and “low” culture in different ways.

Film Culture and the Urdu Public

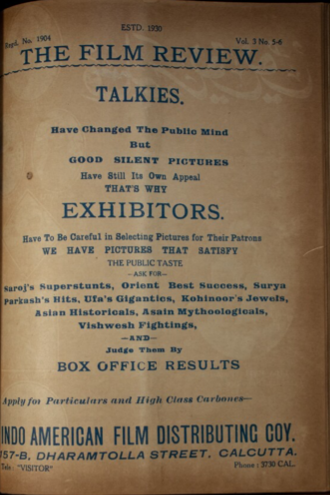

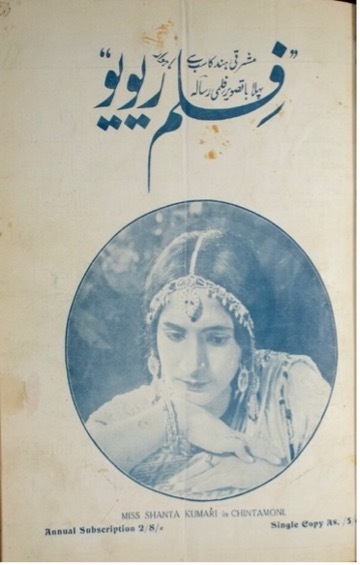

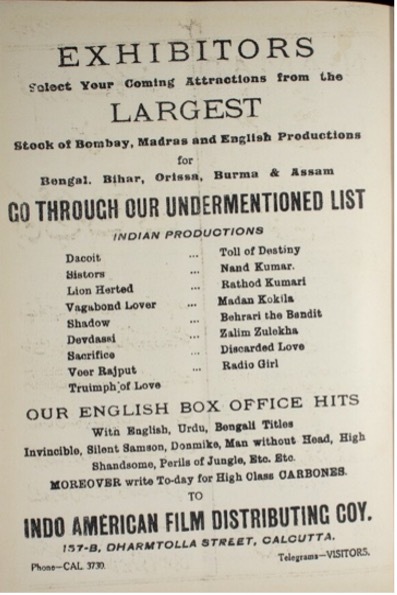

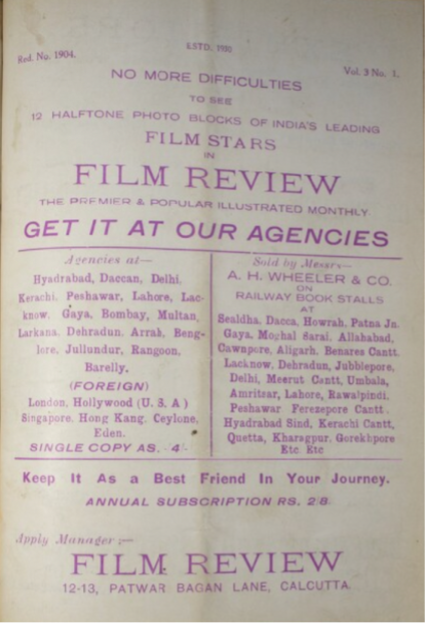

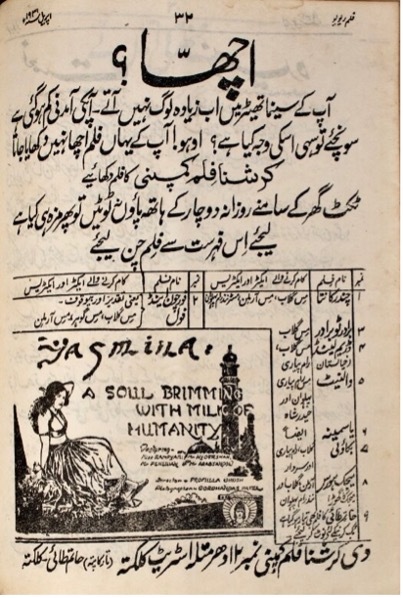

The cover pages often offer the first clues about the audiences Urdu film magazines were addressing. The Film Review, established in 1930 in Calcutta, defined itself as the film magazine of mashriqi (eastern) India (Fig. 2), but this strong regional claim did not restrict the cinema public it was addressing. Publicity material across the magazines shows that the pre-Independence film-production business during the 1930s was scattered across a range of locations: Calcutta, Lahore, Bombay, and to some extent Delhi were the cities where noteworthy production companies were based (Fig. 3).

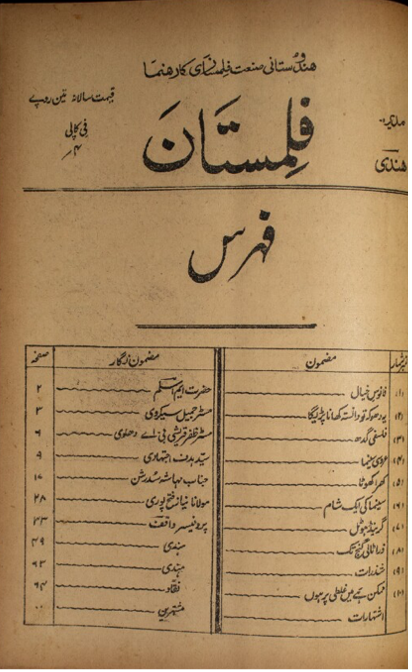

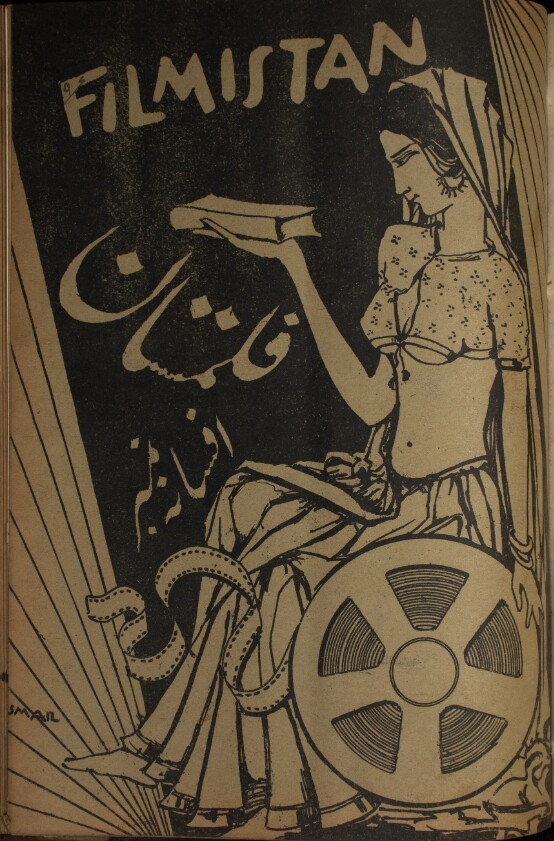

There is no indication of regional insularity in the way that the films were presented in Urdu magazines since, regardless of origin or language, they were framed as part of a wider market of “Hindustani” cinema—a collective imagination that overlapped with Urdu’s transregional spread as a lingua franca. Both the pseudonymous stylings of Filmistan’s editor as “Hindi” and the title dedication of the magazine evoke this transregional “Hindustani” imagination that is woven together by Urdu (Fig. 4).

Image Courtesy: The British Library, EAP1262/1/3/2, https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP1262-1-3-2

Moreover, the magazines themselves originated from regions just as disparate as the film industries they marketed—ranging from Calcutta (The Film Review and Film Star) to Lahore (Filmistan)—drawing attention to the expansive regional spread of the Urdu-speaking cinema-viewing publics being addressed. For instance, an advertisement in The Film Review alerting readers to the publication’s vast circulation network lists not only the Indian and foreign agencies but also the railway book stalls selling the magazine. These extended from Dhaka (Dacca) in the east which comprises present-day Bangladesh all the way up to Peshawar on the northwestern reaches of what is now Pakistan (Fig. 5).

The frequent and generous use of English across Urdu film magazines—with advertisements, film publicity material, and even cover pages of Urdu film magazines often appearing entirely in English—suggests a substantial transnational and multilingual audience. The tagline at the bottom of the page shown in Fig. 5 urging buyers to pick up a copy for their journey indicates that the magazines were largely ephemeral objects meant to be consumed as quick, on-the-go, pulpy pleasure reads. Finally, the ad’s emphasis on railway stalls as primary nodes of distribution and the explicit framing of consumers as travelers pointedly evokes an Urdu cinema public that was just as mobile and regionally porous as it was multilingual.

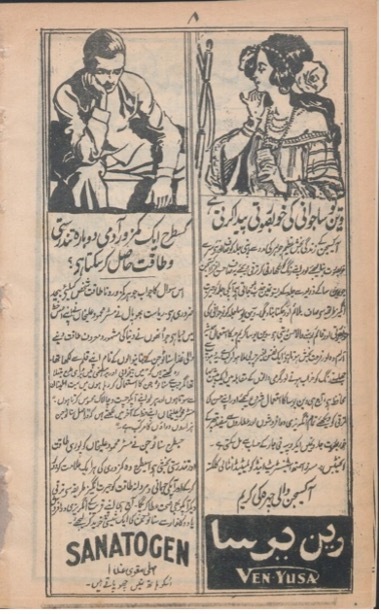

Advertisements targeting emerging middle-class interests were certainly not features unique to film-oriented magazines, as Urdu literary publications carried eclectic and visually evocative advertisements for new commodities and technologies that were visually keyed into the cosmopolitan character and consumerist impulses of Urdu periodical culture (Fig. 6).

Participating in the same consumer-aware print culture, Urdu film magazines displayed a much more direct and transparent understanding of their audience as consumers, and at the same time, films tended to be presented explicitly as commodities. This can, for example, be seen in a recurring ad template for Calcutta’s Krishna Film Company in The Film Review that extols the good quality of its film products to potential exhibitors, while also playfully evoking the mazah (pleasure) of a crowd mobbing the theater’s ticket window (Fig. 7). By evoking filmgoers as unruly masses, the ad also encapsulates thematic tensions in film-culture discourse, examined in the following section, which show that even as film magazines leaned into cinema as a trade and business, the way they imagined cinema-viewing publics was laden with both excitement and anxiety about public cultures derived from the bazaar, street, and quotidian life.

Gender, Urdu, and the Film Bazaar

In Filmistan’s 1932 afsana (story) issue, a regular opinion column by an anonymous critic vehemently derides filmmakers for including unnecessary bazaari (commercial songs) to ensure their films’ success.3Naqqad, “Mumkin hai mein ghalati par hoon” [“I could be wrong . . .”], in afsana (story) issue, Filmistan, 1931, p. 64. The descriptor bazaari acknowledges the popularity of the songs while also pejoratively considering them lowly and crass. The column exemplifies how textual discourses on twentieth-century Urdu film magazines played into and perpetuated respectability politics by deriding the corrupting influences of the bazaar. Their visual culture, however, simultaneously undercuts this moralizing by magnifying the bazaar-associated sensibilities that had been absorbed into films. Relying heavily on cinema’s visuality, film magazines made generous use of glossy film stills, which is most evident in the great emphasis the publications put on being ba-tasveer (illustrated), that is, on including image supplements that usually carried half-tone photo blocks. The Film Review’s aforementioned full-page advertisement for its distribution agencies leads with the availability of half-tone photographic stills, establishing the inclusion of pictures as a key attraction and selling point for the magazine itself (see Fig. 5).

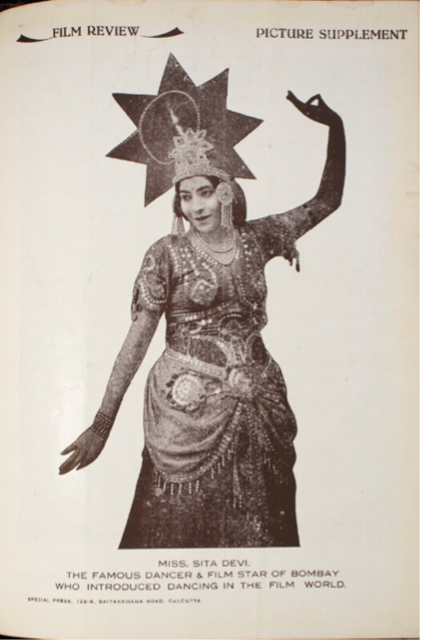

The most notable element of Urdu film magazines’ visual culture are the subjects of these images: female performers (dancers, singers, actresses, etc.) who are featured variously, in staged studio photographs, film stills, and illustrations (Figs. 8–10).

The illustrated cover of a 1931 issue of Filmistan’s special afsana issue (Fig. 8) depicts a provocatively dressed and sensuously postured woman as the literal conduit between literature and cinema. This imagery captures the sharply classed and gendered anxieties that films triggered by steadily blurring the boundaries between literary/“high” and popular/“low” cultures. The image underlines the contradictory impulses of Urdu print culture through the 1930s, when ideas of competitive nationalisms and social reformism awkwardly jostled for space with depictions of vanity, indulgence, leisure, and consumerism.

The ubiquity of feminine imagery attests that films made women, who in general had thus far been reduced to passive subjects of reformist and nationalist agendas, increasingly and dramatically more visible in the public sphere. Since the actresses of early Hindustani films usually came from courtesan lineages, they were socially marginalized, but cinema enabled them to craft something akin to professional identities.

The visual and public displays of the female body and feminine sensuality, however, ran afoul of the respectability politics that dominated twentieth-century Urdu print-literary discourses. A poem in an issue of Film Star magazine reflects the moral anxieties triggered by the social transgression of female performers in the public eye. Addressing an idealized actress through the conventional aashiq-mashuq (lover-beloved) tropes of the classical Urdu ghazal, the poet describes her as the beloved who possesses mesmerizing beauty, grace, and charm. Though the paeon soon devolves into scorn as the poem pivots to interrogating the actress’s honor (or lack thereof):

O one from this humble earth, where is your destination?

Do you come from within four walls (home) or the market?

If you are honorable, then you are a beacon of beauty without question;

and if not, then get off the stage, for you are simply without shame.4aye mae-arzi, haqeeqi, teri manzil hai kahaan? / chaar deewaar se ya bazaar se aayi ha tu? / hai agar ba-ismat, toh beshak husn ka tara hai tu, / varna chhor stage, neeche aa, ke aawaraa hai tu. Mohammad Sadiq Zia, “Film-Stage ki Mallika Se” [“An Ode to the Film-Stage Actress”], Film Star, 1933, p. 17. Translations by the author.

Apart from invoking the gendered private-versus-public divide that is typical of nineteenth century nationalist-reformist discourse, the poem specifically shows that the bazaar emerged as the lynchpin for anxieties about cinema in general and performing women in particular.

Conversely, conservative attitudes were also satirized in Urdu film magazines that gave voice to a range of opinions and commentary, including expressions of the new indulgences and pleasures that films afforded. A frequent satirical column titled “Gulabi Urdu” (Garbled Urdu) in The Film Review in 1931, penned anonymously under the moniker “Mulla Rumuzi,” plays with notions of adab (refinement) and sharafat (respectability) and mocks elite perceptions of cinema as the bawdy circus for the gawars (uncultured masses).5Mulla Rumuzi, “Gulabi Urdu,” The Film Review, 1931, pp. 18–19.

Another article by an anonymous author in Filmistan expresses the exciting new modes of sociality that films were shaping through the trope of tafrih (enjoyment).6Neyaz Fatehpuri, “Cinema ki ek shaam,” in afsana (story) issue, Filmistan, 1931. Adopting the perspective of a young male flaneur enjoying the big city, the article describes the distinct pleasure of watching thrilling adventures in a cinema as part of a crowd. Cinema here is characterized as a form of tafrih for a rangeen pasand tabqa, or a colorful (leisure-loving) social group, a mildly derisive descriptor identifying the typical cinemagoer as a city slicker with money to burn. In addition to being a specifically urbane pastime, cinema-going is also cast by the article as a gendered activity that imagines the cinema theater as a space occupied exclusively by men.

At the same time, the vision of film viewing as an avenue for male homosociality conjures tropes of early modern literary traditions like rekhti poetry, particularly the shahr ashob genre, which describes a young urbane dandy exploring the city and romancing young male paramours. Immersed in sensuality, rekhti poems express all manner of bodily and sensory pleasure with witty abandon, and they explicitly evoke homosexual desire.7Sunil Sharma, “The City of Beauties in Indo-Persian Poetic Landscape,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 24, no. 2 (2004): 73–81. Such transgressive themes were derided by male literary elites whose views channeled Victorian ideals on gender and sexuality and sealed off Urdu literary genres into separate silos of “masculine” and “feminine.”8Frances W. Pritchett, Nets of Awareness: Urdu Poetry and Its Critics (University of California Press, 1994), 172. Despite the mapping of these notions and attitudes onto early Hindustani cinema, cinema and film culture went a long way in allowing Urdu to transgress and transcend text-centered discourses in the twentieth century.

These examples show that Urdu film magazines, in both form and content, offer considerable insights that deepen the history of both film and Urdu in late colonial India and also highlight how they intersect and influence each other. The tensions in textual-visual discourses in Urdu film magazines reveal that cinema’s embrace of the bazaar in particular—as a space of social, cultural, linguistic, and gendered mixing and as a site of tafrih—animated uses, arenas, and publics for Urdu beyond the literary at a time when dominant discourses advocated for excluding entire vocabularies, registers, and indeed non-elite social worlds from the Urdu public. Early Urdu film magazines and other remnants of popular-culture ephemera therefore deserve to be analyzed more closely. Rather than simply folding its postcolonial history into totalizing narratives of national language politics and institutional erasures, Urdu film magazines have the potential to throw open discussions on the alternate lives of Urdu in twentieth-century India.

- 1See, for example, Debashree Mukherjee, Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020); and Manishita Dass, Outside the Lettered City: Cinema, Modernity, & the Public Sphere in Late Colonial India (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- 2Preserved and digitized by the Shabistan Film Archive, Bangalore, and the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme.

- 3Naqqad, “Mumkin hai mein ghalati par hoon” [“I could be wrong . . .”], in afsana (story) issue, Filmistan, 1931, p. 64. The descriptor bazaari acknowledges the popularity of the songs while also pejoratively considering them lowly and crass.

- 4aye mae-arzi, haqeeqi, teri manzil hai kahaan? / chaar deewaar se ya bazaar se aayi ha tu? / hai agar ba-ismat, toh beshak husn ka tara hai tu, / varna chhor stage, neeche aa, ke aawaraa hai tu. Mohammad Sadiq Zia, “Film-Stage ki Mallika Se” [“An Ode to the Film-Stage Actress”], Film Star, 1933, p. 17. Translations by the author.

- 5Mulla Rumuzi, “Gulabi Urdu,” The Film Review, 1931, pp. 18–19.

- 6Neyaz Fatehpuri, “Cinema ki ek shaam,” in afsana (story) issue, Filmistan, 1931.

- 7Sunil Sharma, “The City of Beauties in Indo-Persian Poetic Landscape,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 24, no. 2 (2004): 73–81.

- 8Frances W. Pritchett, Nets of Awareness: Urdu Poetry and Its Critics (University of California Press, 1994), 172.