Curator Juliet Kinchin addresses graphic images that spurred revolution in Budapest in 1919.

Many avant-garde movements in Europe around the time of World War I were linked to radical politics, and in those stormy years, a generation of artists in Budapest created provocative newspaper illustrations, banners, and public posters in a new genre of graphic design that was both artistic and unequivocally political.

In recent years, MoMA has been able to build up an important collection of these early modernist Hungarian materials, including posters from the collection of Julius Paul (1867–1938). Amassed during Paul’s lifetime, his was one of the great collections of Central European posters from the early twentieth century. Born in Hungary, Paul owned a cigarette-paper distribution company based in Budapest and Vienna and was a founding member of Hans Sachs’s Verein der Plakatfreunde. 1Paul died in Vienna a few months before the Anschluss (annexation) of Austria by Nazi Germany. As he had no children, shortly after his death in 1938 his widow gave his collection to their nephew in hopes it would facilitate his emigration. The nephew was unable to export the collection and apparently left it in his apartment in Vienna. In 2005, a researcher at the Albertina found the 1938 exit visa of Julius Paul’s nephew, which listed the poster collection as one of his assets, and a process of restitution was started, leading to its sale in 2008–09. Among the works acquired by MoMA are a series of visually compelling posters created by prominent Hungarian artists Mihály Biró, Sándor (Alexander) Bortnyik, and Bertalan Pór in the buildup to 1919, the year of the rise and fall of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet regime.

On March 21, 1919, Bolshevik forces led by Béla Kun declared the Hungarian Soviet Republic, replacing the short-lived Hungarian Democratic Republic. Biró, Bortnyik, and Pór all fought with the Hungarian Red Army as combatants and graphic propagandists. They were offered direct roles in shaping the culture of the new society and sought to mobilize thousands of unemployed workers, idle soldiers, and war invalids in the struggle for a world revolution. But the takeover lasted a mere 133 days, at the end of which first the Romanian army and then a counterrevolutionary regime seized power. Fleeing the “white terror”—a wave of vicious reprisals that followed the collapse of the Bolshevik republic—Biró, Bortnyik, and Pór became refugees, moving among European countries to escape arrest and execution and contributing to avant-garde developments in centers including Vienna, Moscow, and Berlin, and in the Bauhaus in Weimar Germany.

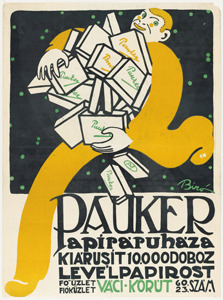

Before 1919, Budapest, the thriving metropolis of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was already developing as a center of modern poster design, and Mihály Biró was one of Hungary’s best-known graphic artists for commercial and political commissions. Through distortion of scale and angle, and dramatic simplification of form and color, Biró created an image of a delivery boy leaping toward the viewer, scattering Pauker stationery products in his haste. Such posters vividly communicate a sense of the congestion and frenetic pace of business in Budapest before World War I. Alluding to his bold use of color, the German magazine Das Plakat (The Poster) described Biró’s visual language as throbbing with “the syncopated rhythms of the Hungarian folk songs.”

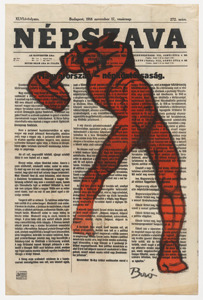

Among Biró’s most iconic images is Red Man with a Hammer. Originally designed in 1912, it became inextricably linked with the 1919 Hungarian Revolution, appearing in huge numbers and varied formats—overprinted in this case with an issue of Népszava (The People’s Voice), the newspaper of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party. The image established Biró’s name internationally and has been much repeated in Central European political iconography up to the present day. As an apprentice in Charles Robert Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft in London, Biró learned the craft of printing and absorbed the socialist ethos and utopian ideals of the British Arts and Crafts movement. His earlier training as a sculptor is also evident in the assured handling of the iconic red man, the model for whom was his lifelong friend, the Hungarian wrestling champion Tibor Fischer.

The designing of political posters demands not only technique and ability to draw but also that the artist should be in close touch with the masses of the people to whom his poster is to appeal . . . These posters intended to work upon the masses must be true art, drawn as simply as possible, and always taking mass psychology into account. “Sachlichkeit” [descriptive representation] puts a brake upon the artist’s energy and hinders every vigorous stroke with which he ought to hammer his poster into the public’s head.

—Mihály Biró, interviewed in the German periodical Gebrauchsgraphik, 1932

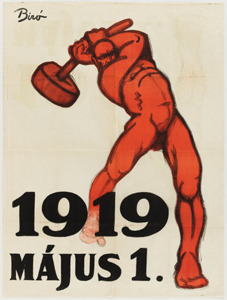

MoMA is also fortunate to own a later adaptation of Red Man with a Hammer, one of many produced during the tumult of Hungary’s 1919 revolution. The poster advertised May Day, a holiday associated with the international worker’s movement, the celebration of which would be the biggest public event during the 133 days of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic. Embodying the energy of the revolutionary masses, Biró’s red man glorified the common worker as the equivalent of a mythological figure such as Hercules, or Vulcan at his forge. The concept of posters as public decorations for May Day was at least partly inspired by Soviet Russian precedents. “The defiant simplicity, the removal of peripheral things, and the menacing power of the delivery—all these are the hallmarks of Biró,” wrote the critic Pál Nadái at the time.

Another poster that remains one of the most memorable images associated with the Hungarian Revolution of 1919 is Világ Proletárjai Egyesüljetek! (Proletarians of the World, Unite!). Striding forward in tandem and bearing elongated red banners beneath the title’s slogan, two nudes of epic scale, set within in a whirling composition, communicate nervous energy and urgency. Naked and classicized, the figures recall Cézanne’s Bathers, but they also symbolize the universality of the revolutionary impulse. After the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, Bertalan Pór spent more than a decade as a political refugee before returning to Hungary once a Communist regime was established following World War II.

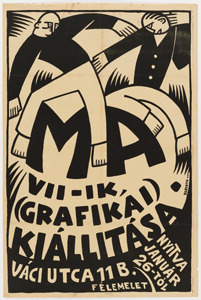

This rhythmic and intense composition featuring energetic figures contained by a rectangular field captures the turbulence of the era and a burgeoning taste for Futurist and Expressionist design. The poster publicizes an exhibition by Ma (“Today” in Hungarian), a group that emerged during World War I and which quickly became a leader in the Budapest avant-garde. The first issue of its journal set its revolutionary tone and simultaneously sums up the role of these graphic arts during this era of revolutionary fervor: “The new painter is a moral individual, full of faith and a desire for unity! And his pictures are weapons of war!”

Within a few years, Bortnyik had broken from the Ma group, and in 1922, he joined the flow of Hungarians (among them Marcel Breuer, László Moholy-Nagy, Ferenc Molnár, Gyula Pap, and Andor Weininger) to the Weimar Bauhaus. He remained on the periphery of this group, however, and in 1924 returned to Budapest where he set up his own art school based on Bauhaus principles in 1928. After World War II and the establishment of a communist government, the paths of Biró, Bortnyik, and Pór briefly converged once more in Budapest. Biró, his health now irrevocably damaged by incarceration, was literally carried back from Paris by his wrestler friend Tibor Fischer in 1947, only to die shortly thereafter. Pór also returned from Paris to take up a post in the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts, where Bortnyik had become the director. Both remained in Hungary until their respective deaths.

- 1Paul died in Vienna a few months before the Anschluss (annexation) of Austria by Nazi Germany. As he had no children, shortly after his death in 1938 his widow gave his collection to their nephew in hopes it would facilitate his emigration. The nephew was unable to export the collection and apparently left it in his apartment in Vienna. In 2005, a researcher at the Albertina found the 1938 exit visa of Julius Paul’s nephew, which listed the poster collection as one of his assets, and a process of restitution was started, leading to its sale in 2008–09.