This essay revisits the starting points of the project Communicating Difficult Pasts, which curators and researchers Margaret Tali and Ieva Astahovska initiated in 2018 while searching for new ways to artistically and curatorially explore the twentieth-century history of the Baltic region and its ongoing impact. Exchanges and discussions that they facilitated in the broader region around the Baltic states revealed many shared narratives of memory within a still-to-be-written history of the twentieth century. Opening up questions related to transnational memory, trauma, silences, and lack of representation of the darker sides of this history, the project also created new solidarities.

Baltic history, with its different colonial occupations and military conflicts, is so complex that it is often difficult to make sense of it to outsiders without simplifying it significantly. We have continued to use Western categories in art and cultural history to describe it, when in fact, new frameworks and concepts are necessary to articulate it for both ourselves and others. The needs to decolonize knowledge and to create new solidarities were crucial motivations in initiating Communicating Difficult Pasts, a collaborative project that we started as curators positioned within and outside the region, in Rotterdam/Tallinn and Riga, respectively.1Ieva Astahovska works at the Latvian Center for Contemporary Art in Riga, and Margaret Tali works at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture in the Estonian Academy of Arts and shares her time between Rotterdam and Tallinn. We wished to gather younger-generation researchers around the twentieth-century past, and also to engage artists in exchanges about the subject of communicating legacies of violence.

Dealing with local histories of conflict, violence, and war has been anything but common in the art history of the Baltic region. Over the past thirty years, since the dissolution of the Soviet Union and its censorship practices, when it has been possible to discuss history openly again, artists and curators have predominantly concentrated on the myriad social problems of the present. Perhaps symbolically, our collaboration began with organizing a workshop in Riga that dealt with ways of overcoming the competitive environment of the neoliberal art world.2Our workshop “Doing Things with Words under Neoliberalism” (2018) took place in Riga as a part of the program “Language from Practice to Action,” which was curated by Maija Rudovska and Inga Lāce. As we brainstormed how to turn moments of competition into something more productive, we began to collaborate.

Communicating Difficult Pasts brought together artists, scholars, and curators in three contexts: the summer school by the same name in Kuldīga, Latvia; the symposium “Prisms of Silence” in Tallinn at the Estonian Academy of Arts; and the exhibition Difficult Pasts. Connected Worlds at the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga. We received organizational support from the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art for the summer school and exhibition, whereas the symposium was supported by the Estonian Academy of Arts. We approached these events as equal in weight—as the problems and themes under discussion continued to build upon each other. We commissioned several new artworks that were created as a part of larger conversations involving the symposium and/or the summer school, and it’s fair to say that with most of our long-term collaborators, we have indeed been thinking together. In this essay, we will discuss our curatorial and artistic research methods by highlighting works by artists Zuzanna Hertzberg, Vika Eksta, and Quinsy Gario that have grown out of the project.

Connecting Geographies, Creating Solidarities

The Baltic states are located between Russia, Scandinavia, and other Eastern European countries including Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland. Yet this region has remained under-researched, even within Eastern European history, as larger countries like Poland and Hungary have offered more common contexts, examples, and cases. Although the Baltic states share aspects of their collective history with these countries, as they do with Russia, Germany, and Scandinavia, their individual histories are more specific. The region has been culturally and ethnically diverse throughout its history, but in the Soviet era, was subject to repression and the erasure of many cultural minorities. The borders of the Baltic countries shifted several times in the twentieth century and continued to remain in dispute after the region regained independence in 1991. In Communicating Difficult Pasts, we sought out transnational and transcultural connections and their entangled developments, proposing to approach the Baltic states in their broader geographical context as a Baltic region of memory.3The notion of a “region of memory” was proposed by sociologist Jeffrey Olick in Jeffrey K. Olick, foreword to Memory and Change in Europe: Eastern Perspectives, eds. Małgorzata Pakier and Joanna Wawrzyniak (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2016), xi.

For instance, the summer school in Kuldīga bridged Baltic history with that of Scandinavia, particularly through parallels with the indigenous Sámi community in Norway (Máret Ánne Sara); connections to Finland (Harri Pälviranta); and the experiences of the Jewish émigré community in Israel, many of who escaped the Baltic states during World War II and then emigrated in the 1970s (Adi Kuntsman, Ilya Lensky, Violeta Davoliūtė). We mapped out themes and further focuses, creating solidarities across these contexts. In the symposium in Tallinn, however, we sought to elaborate on the vocabulary of shared traumas in the Baltic region of memory as well as in a global context. In both events, we involved more experienced scholars to further the discussion of concepts and frameworks, and explored ways of understanding contemporary social change through the various silences about World War II, its aftermath, and the Soviet era. Our edited special issue of the Baltic Worlds journal, Confronting Muted Memories (Winter 2020),4This special issue, which includes ten contributions by artists and scholars, is available online. See Confronting Muted Memories: Reading Silences, Entangling Histories, special issue of Baltic Worlds 13, no. 4 (December 2020), http://balticworlds.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BW-2020-4-OA-VERSION-pdf.pdf. which grew out of this event, brought together this research and advanced our vocabulary and frames of understanding. The exhibition further connected these themes and built upon them with newly developed works in combination with existing artistic research.

The works exhibited in Difficult Pasts. Connected Worlds brought together contexts such as Ukraine, Chechnya, Siberia, Afghanistan, Poland, and the Caribbean island of Tobago in rethinking Baltic history and opened up subjects that have either been hidden or erased altogether. Nevertheless, these silenced events, which remain invisible in the public context, continue to influence local people and cast shadows on their lives in significant ways.

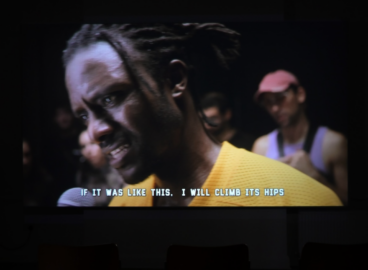

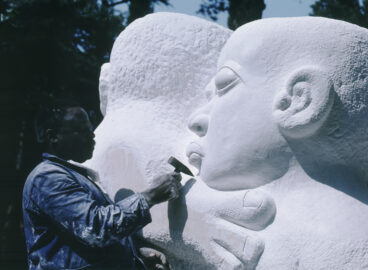

When he gave us a tour of Kuldīga, Ilya Lensky, director of the Museum “Jews in Latvia,” noted the town’s transatlantic colonial heritage advanced by seventeenth-century Baltic-German duke Jakob Kettler as well as its Jewish past—which despite the fact that in the late nineteenth century, almost half of the inhabitants were Jewish, remains silenced. While Kuldīga’s Jewish past has been largely unacknowledged, if not forgotten, the colonial quests are commemorated in a prominent statue set up to Kettler in the heart of the town in 2012. In 2020, at our invitation, Quinsy and Jörgen Gario, Dutch artists of Caribbean origin, gave a spoken-word and live-music performance How to See the Spots of Der Leopard5Quinsy Gario edited the documentation of the performance into a separate work, which is available online. See Quinsy Gario, How to See the Spots of Der Leopard, e-flux Architecture, October 15, 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/monument/355475/how-to-see-the-spots-of-der-leopard. in Kuldīga. Quinsy Gario built the performance up as a trap,6Quinsy Gario, Jörgen Gario, and Redi Koobak, “How to See the Spots of the Leopard: An Interview with Quinsy Gario and Jörgen Gario,” in Postcolonial and Postsocialist Dialogues: Intersections, Opacities, Challenges in Feminist Theorizing and Practice, eds. Redi Koobak, Madina Tlostanova, and Suruchi Thapar-Björkert (London and New York: Routledge, 2021), 182. posing questions to the audience about their nostalgia for the past. Gradually connecting their responses with capitalism, the slave trade, and the ongoing impact of both in the present, he made the public feel more and more uncomfortable. Jörgen Gario joined the performance, playing steelpan and kokle, traditional instruments from the Caribbean and Latvia, respectively, while Quinsy draw the map of Tobago next to the monument, hence localizing, visualizing and familiarizing its present and history through music and storytelling. Their perspectives opened, in the Latvian context, a window to this colonialism, which had remained unconsidered, and as a part of our project, spurred discussion as well as new solidarities.

Transmitting Uncomfortable Histories via Art

Our project sought to bring together researchers and artists to look for new ways of acknowledging, caring for, and reconciling with the past. It thus gave new sensibilities and reflexivity to dealing with the different commonly silenced subjects, while also creating spaces to share research methods, concepts, and frameworks across art and theory. Different discussions revealed the productivity and significance of connecting affect with history. The most important approaches to emerge in the context of working with limited and often distorted material were oral history, body memory, postmemory,7Feminist scholar Marianne Hirsch has conceived “postmemory” in reference to the second generation, i.e., the daughters and sons of Holocaust survivors, and their relation to their parents’ traumatic experiences. However, it has recently been applied to the much broader transgenerational impact of traumatic memories. work with diaries, conversations and dialogues, as well as collaboration with family members and/or with communities of victims. These artistic research strategies are not just reflective, but also active and emancipatory in their memory work, which brings together different layers of imagination and integrates ethical concerns. They enable users to employ different microhistories that have been made absent from dominant historical memory, bringing more complexity and nuance to their understanding of the past. At the same time, they address contemporary reality through the past, such as the alarming growth of far-right movements; they empower and increase the agency of women and minority communities; and they revisit the longevity of colonial legacies.

Such a multilayered artistic strategy was exemplified by feminist artivist (artist + activist) Zuzanna Hertzberg, who introduced with it in the symposium in Tallinn and in her work Volunteers for Freedom (2016–20) in the exhibition in Riga. An investigation of the neglected memory of minorities and women, this installation consists of wooden boxes with biographical collages that include archival documents and photographs on one side, and affective colorful paintings on the other. In combination, this material portrays the Jewish Polish and Jewish Latvian women who fought for the Spanish Republic as part of the International Brigades against General Francisco Franco and theNationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). They volunteered to join the war despite facing the expansion of far-right and anti-Semitic ideologies in Europe. Between forty thousand and fifty-nine thousand male and female volunteers from fifty-three countries fought as foreign volunteers, making it one of the largest international solidarity actions to date. Though women from all over the world were involved in combat, marking the start of an important phase of women’s political activism, their role in this struggle has been almost entirely forgotten by patriarchal history. In commemorating these women, the artist restores their visibility and the memory of selected fighters, and speaks out about women’s struggle for equal rights. Thereby, she confronts the “monolithic” historical memory that is often instrumentalized in the creation of national myths and, in its place, proposes a nomadic memory, one that crosses boundaries and unites diverse groups, encompassing their shared aspirations and emotions.8Zuzanna Hertzberg, “Nomadic Memory. Artivism as the Practice of Recovering Memory,” Confronting Muted Memories, 20–27, http://balticworlds.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BW-2020-4-OA-VERSION-pdf.pdf. Hertzberg combines the installation Volunteers for Freedom with spoken-word performances that discuss the women and their life stories in order to resist historical erasures. In the performative component, she explains her artivist stance and facilitates conversation between the portrayed women, herself, and her audience.

In her work Conversations with Dad (2020), Latvian artist Vika Eksta confronts the silence around the largely forgotten Soviet-Afghan War (1979–89), the most brutal military conflict of the late Soviet period. More than fifteen thousand Soviet soldiers were killed, while on the Afghan side, about one million people died, most of them civilians. The artist’s father was one of the ten thousand soldiers drawn into the conflict from the Baltic republics against their will, assigned to the Soviet army on a mandatory basis. Even though many of these people are still among us, to date, they have not received psychological assistance in dealing with this traumatic experience—nor have their families. The physical and psychological wounds left by this war—and the silence surrounding them—still impede its memory, since after regaining independence, there was little willingness to deal with this “foreign” war of the collapsed Soviet empire in the Baltics countries. Also, the relatives of former soldiers continue to live with these experiences. Even though the wounds are not “theirs,” they too are impacted by them through the postmemory of their parents—like the artist who is affected by this past through her father’s behavior, and its impact on family relationships. Eksta integrates different narrative and visual media in her work—a map of Afghanistan, the collection of letters her father sent to her mother when he was away at war, her father’s army photographs, and the shoulder marks on his military uniform. In the heart of this multimedia installation is the video in which the artist insistently questions her father about his wartime experiences, which, as he says, “no one wants to remember.” She keeps on asking, and through her persistence, succeeds in overcoming the taboo and to shift something that has been muted for decades. Along with her father, she is the protagonist of her video, and their dialogue is the main medium of communicating past traumas, processing suppressed memories, and reaffirming the father-daughter bond.

Conversation is a significant unifying element among the works in the exhibition and project as a whole, involving both curated and spontaneous discussions. For instance, both Volunteers for Freedom and Conversations with Dad portray people whose involvement in past, transnational wars reveals poignant shifts in the socialist and leftist histories of our region—from solidarity and the idealistic beliefs about equality that united thousands of people all over the world to a discredited, brutal, and deceptive system that abused and destroyed its own people. Yet these artworks suggest possibilities for changing the understanding of these events and offer perspectives of hope—if we cannot transform the past, we can at least acknowledge its impact and work to “repair” the present.

In Conclusion: Connecting Traumas and Connecting Histories

In the course of the many difficult conversations we came to hold about Baltic history in the global world, we realized that there is something liberating about connecting the different traumas, and discussing and researching them in relation to each other. Sometimes this effort was seen as confusing in response to the exhibition. However, in our heterogenous communities, where such connection has often been negated, different traumas continue to impact us on a daily basis—mostly in ways that remain unexpressed and publicly invisible. Many narratives of memory have a lot in common in the Baltic region of memory, and it is through transnational and transcultural perspectives that “the shared” can be made available through artistic and scholarly memory work.

Unacknowledged sides of the past acquire lives of their own and resurface in unexpected ways. Through comparison, and by seeing things in relation to each other, important aspects of history can be foregrounded. The discussions facilitated by our project have contributed to making Baltic history not only more connected and global, but also more graspable through the exchange of recent research. The difficulties that artists and scholars face often prove to be shared, too, whereas artists’ creative processes have introduced new ways of approaching such issues. While trauma, with its complexities and hidden sides, is a heavy burden, its reworking can offer new solidarities and add new depth to understanding other subjects in more nuanced ways. With its many synergies, Communicating Difficult Pasts has offered new approaches and added to the collective knowledge of Baltic history and consciousness regarding the need for its sensitive mediation and curation.

The exhibition Difficult Pasts. Connected World (November 27–December 20, 2020) was held at the Latvian National Museum of Art. It included works by Aslan Ġoisum, Jaana Kokko, Quinsy Gario, Lia Dostlieva, Andrii Dostliev, Paulina Pukytė, Ülo Pikkov, Vika Eksta, and Zuzanna Hertzberg.

- 1Ieva Astahovska works at the Latvian Center for Contemporary Art in Riga, and Margaret Tali works at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture in the Estonian Academy of Arts and shares her time between Rotterdam and Tallinn.

- 2Our workshop “Doing Things with Words under Neoliberalism” (2018) took place in Riga as a part of the program “Language from Practice to Action,” which was curated by Maija Rudovska and Inga Lāce.

- 3The notion of a “region of memory” was proposed by sociologist Jeffrey Olick in Jeffrey K. Olick, foreword to Memory and Change in Europe: Eastern Perspectives, eds. Małgorzata Pakier and Joanna Wawrzyniak (New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2016), xi.

- 4This special issue, which includes ten contributions by artists and scholars, is available online. See Confronting Muted Memories: Reading Silences, Entangling Histories, special issue of Baltic Worlds 13, no. 4 (December 2020), http://balticworlds.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BW-2020-4-OA-VERSION-pdf.pdf.

- 5Quinsy Gario edited the documentation of the performance into a separate work, which is available online. See Quinsy Gario, How to See the Spots of Der Leopard, e-flux Architecture, October 15, 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/monument/355475/how-to-see-the-spots-of-der-leopard.

- 6Quinsy Gario, Jörgen Gario, and Redi Koobak, “How to See the Spots of the Leopard: An Interview with Quinsy Gario and Jörgen Gario,” in Postcolonial and Postsocialist Dialogues: Intersections, Opacities, Challenges in Feminist Theorizing and Practice, eds. Redi Koobak, Madina Tlostanova, and Suruchi Thapar-Björkert (London and New York: Routledge, 2021), 182.

- 7Feminist scholar Marianne Hirsch has conceived “postmemory” in reference to the second generation, i.e., the daughters and sons of Holocaust survivors, and their relation to their parents’ traumatic experiences. However, it has recently been applied to the much broader transgenerational impact of traumatic memories.

- 8Zuzanna Hertzberg, “Nomadic Memory. Artivism as the Practice of Recovering Memory,” Confronting Muted Memories, 20–27, http://balticworlds.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BW-2020-4-OA-VERSION-pdf.pdf.