“The past must not be forgotten, but the present reminds us of the past, so we must take responsibility for it.” —Romuald Hazoumè1Romuald Hazoumè, interview by the author, April 8, 2024.

Romuald Hazoumè (born 1962, Porto-Novo, Benin) began his artistic training unintentionally. Between the ages of 10 and 12, he made masks as part of a Kaléta group.2Romuald Hazoumè, interview by the author, March 23, 2025. Kaléta is a tradition mainly carried out by children that was imported to the Republic of Benin in the mid-19th century by former Afro-Brazilian slaves who returned to Africa and settled in Benin. Group members perform during popular celebrations such as Christmas and New Year’s. Kaléta places a strong emphasis on playfulness and scenic art, typically comprising singers, musicians, dancers, and mask-makers. Unlike most traditional Beninese masks, which are made from wood, Kaléta masks are made from discarded everyday objects or materials, such as plastic jerrycans or cardboard, making them more varied in shape and color and often more visually flamboyant. When I interviewed Hazoumè in the spring of 2025, he reminisced about making Kaléta masks as a youth, unaware that this process would lead him to become a renowned artist.3Hazoumè, interview, March 23, 2025.

Hazoumè’s special connection to masks comes not only from his engagement with the Kaléta tradition as a child but also from his Yoruba heritage, specifically as it relates to being a descendant of Lali Alomavo, who was a Babalawo (Voodoo high priest) and advisor to King Dê-Sodji (r. 1848–64) of Hogbonou (now Porto-Novo). Yorubas use masks in various rituals and cults, for example, the Gélédé, a ceremony that pays tribute to Iyà Nlà, the Great Mother, and to the role of women in Yoruba society. On this occasion, the men don masks, dance, and sing, sometimes playing satirical or parodic games, to entertain and honor the women.

Heir to these legacies, Hazoumè posits his artworks, whether created individually or collaboratively, as celebratory and commemorative objects through which he can address a range of topics. The artist prefers to use plastic for their fabrication, rather than the wood favored by the Yoruba, as it is more malleable and lends itself readily to various formal and conceptual experimentations.4Hazoumè, interview, March 23, 2025. Since the 1980s, he has collected plastic gasoline jerrycans used by smugglers along the border separating Benin and Nigeria, which he recycles and transforms into mask sculptures, thus creating works that evoke both contemporary geopolitical and economic issues and local tradition. These containers, the same ones that he has used since childhood, remain his go-to material. For him, the geometric forms of traditional African masks are visible in the shapes of gasoline cans and other everyday objects, which he cuts and remakes into what he calls “masque-bidons” or “mask-cans.” In this way, tradition is never too far removed and can be illustrated using nontraditional materials. Hazoumè’s masks are, in effect, “traditional” ready-mades.

In Yoruba culture, each mask has a cultural, social, and spiritual personality. Hazoumè builds on this concept to craft sculptures that serve as documentary portraits. For example, he created a notable piece titled Bororo du Niger in 1992 after meeting a Bororo/Wodaabe man (fig. 1). This artwork features a face of a Wodaabe male adorned in the makeup and jewelry associated with the annual Gerewol festival, a beauty contest in which young men decorate themselves and perform the Yaake, a ritual dance to seduce young women eligible for marriage. Another example of Hazoumè’s documentary masks is Aloda from 1996 (fig. 2). During the period he created this piece, Hazoumè was researching Yoruba women’s matrimonial hairstyles, a coded language that functions as a kind of social identity card. In the precolonial era, a woman’s hairstyle commonly indicated whether she was single, of marriageable age, married, unfaithful, or experiencing issues in her household. The Aloda hairstyle represented in this portrait, with its cornrows covering the entire skull, leaving the top of the forehead clear, suggests that the married woman is at peace in her home. While some artworks dwell on ancestral forms and ritual, others—like Petite from 1999 (fig. 3)—take their cue from modern life and the artist’s personal encounters. Indeed, he conceived of Petite, which he composed using a typewriter and a cleaning brush, as a tribute to a secretary he had met in Cuba. He was struck by her low wage of just $6 a day, especially considering he had just spent $110 in a single day.5Hazoumè, interview, March 23, 2025.

By using discarded everyday objects, especially those made of plastic, Hazoumè critiques the trivialization of the African mask form since the frenzy that emerged in the West in the early 20th century when Westerners first saw the traditional African sculptures and masks brought back from the African colonies by soldiers, missionaries, scientists, and merchants.6See Yaëlle Biro, Fabriquer le regard: Marchands, réseaux et objets d’art africains à l’aube du XXe siècle (Les Presses du réel, 2018); John Warne Monroe, Metropolitan Fetish: African Sculpture and the Imperial French Invention of Primitive Art (Cornell University Press, 2019); and Maureen Murphy, De l’imaginaire au musée—Les arts d’Afrique à Paris et à New York (1931–2006) (Les Presses du réel, 2009). Their presence in the West, and particularly their display in museums, has given them new ethnological and artistic value, distancing them in some ways from their original ritual and cultural significance in Africa. These newly discovered forms captivated Westerners, particularly artists and collectors, and led to their increasing popularity. This growing interest also led to a rise in the trade of counterfeit objects, which persists to this day. As descendants of the Beninese mask tradition, Hazoumè’s works reflect on this frenzy for and ensuing trivialization of the African mask shape through a sarcastic touch that dilutes tradition by using humble materials from consumerist society.

Classical African arts, particularly masks and statues, have been a significant topic of discussion in the relationship between the West and Africa since the 20th century. Does displaying traditional African pieces in Western museums compromise their original nature? Should these works even be housed in Western collections?7It is notable that artists have addressed these questions and others in diverse ways, including in the 1953 short documentary Les statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die) by Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Ghislain Cloquet. This film questions curatorial choices regarding the display of traditional African objects in French museums, serving as an anti-colonialist and anti-racist manifesto. His short documentary, commissioned by the magazine Présence africaine and released in 1953, was censored in France for 11 years due to its anti-colonial content. The 1970 short documentary You Hide Me by Ghanaian filmmaker Nii Kwate Owoo also addresses the issue of the thousands of objects looted from Ghana and Nigeria during the colonial conquests and then buried in storage in the basement of the British Museum. Sub-Saharan African visual artists of the 1960s were not concerned with addressing this subject directly, as they were primarily focused on pursuing modernity through new forms. This pursuit was often achieved through a distancing from traditional African sculpture, as seen in the work of Aina Onabolu (born Nigeria, 1882–1963) or Iba Ndiaye (French, born Senegal, 1928–2008). Alternatively, some artists, like Christian Lattier (born Ivory Coast, 1925–1978), and art movements such as the Zaria Art Society (1958–1962) or the Dakar School (1960s–1970s), have sought to integrate or reinvent traditional African art forms. However, this work seldom directly criticizes the Western world’s relationship with classical African art.

Romuald Hazoumè was one of the first contemporary artists on the African continent to work on the appropriation and reinterpretation of masks.8Following him, other artists have echoed his work, such as Dimitri Fagbohoun (born 1972), who is of Beninese and Ukrainian descent. In his quest to explore his diverse identities, Fagbohoun creates sculptures inspired by his research on traditional African statuary, particularly examples located in private and public collections in the West. Fagbohoun’s work involves reproducing masterpieces of classical African art in materials such as bronze, glazed ceramic, and wood. His aim is to renew a sense of majesty and to create new spaces and opportunities for reflection on the reappropriation of African heritage. Similarly, the artist Wole Lagunju (born Nigeria, 1966), appropriates the heritage of Gélédé Yoruba masks, blending them with Western aesthetic canons to critique colonialism. Deeply rooted in his Yoruba culture, Hazoumè considers himself to be a present-day aré. In the days of the Yoruba kingdoms, the arés were itinerant artists appointed to create art for the royal court who spread their knowledge and culture from kingdom to kingdom. Hazoumè claims to uphold this tradition by spreading his artistic vision across localities where his assembled masks initiate larger debates.

The assemblage of mask-cans is the artist’s favorite technique for installations, allowing him to layer his work with meaning. Displayed together, the mask-cans unite their voices and personalities to convey multiple threads. His mask-cans converge, for example, different temporalities and symbolize the irreducible link between individuals and their history. Indeed, the plastic gasoline containers recovered and transformed into masks by Romuald Hazoumè bear traces of the memories of the individuals who owned them, featured in the touches of blue, red, yellow, white, or green paint on their surface. In Benin, transporters and sellers of smuggled gasoline use distinctive marks not only to identify themselves among each other while trading with Nigeria but also to protect themselves, since the transport of gasoline is a dangerous business. According to the artist, the color refers to the consciousness or unconsciousness of the Beninese individual, which is attached to the Voodoo religion. Indeed, as he explains: “During their childhood at home, the fuel transporters experienced Voodoo ceremonies in their backyards before converting to Christianity or Islam. Growing up in that environment, they learned that, for example, red could be a protective color. Each person thus adopts the cult color that is personal to them at home.”9Hazoumè, interview, April 8, 2024. Red refers to the Voodoo cult of Shango, the god of justice, lightning, and thunder; blue to the cult of Yemaya, the goddess of the sea; yellow to the cult of Elegba, the god of encounters and an intermediary between other Voodoos; white to the cult of Damballah, the god of fecundity; or green to the cult of Oduduwa, the creator god. Thus, these mask-cans, through color, represent, for the artist, the faces of the individuals who once carried them. Their assemblage in installations enables the artist to tackle a variety of societal discourses.

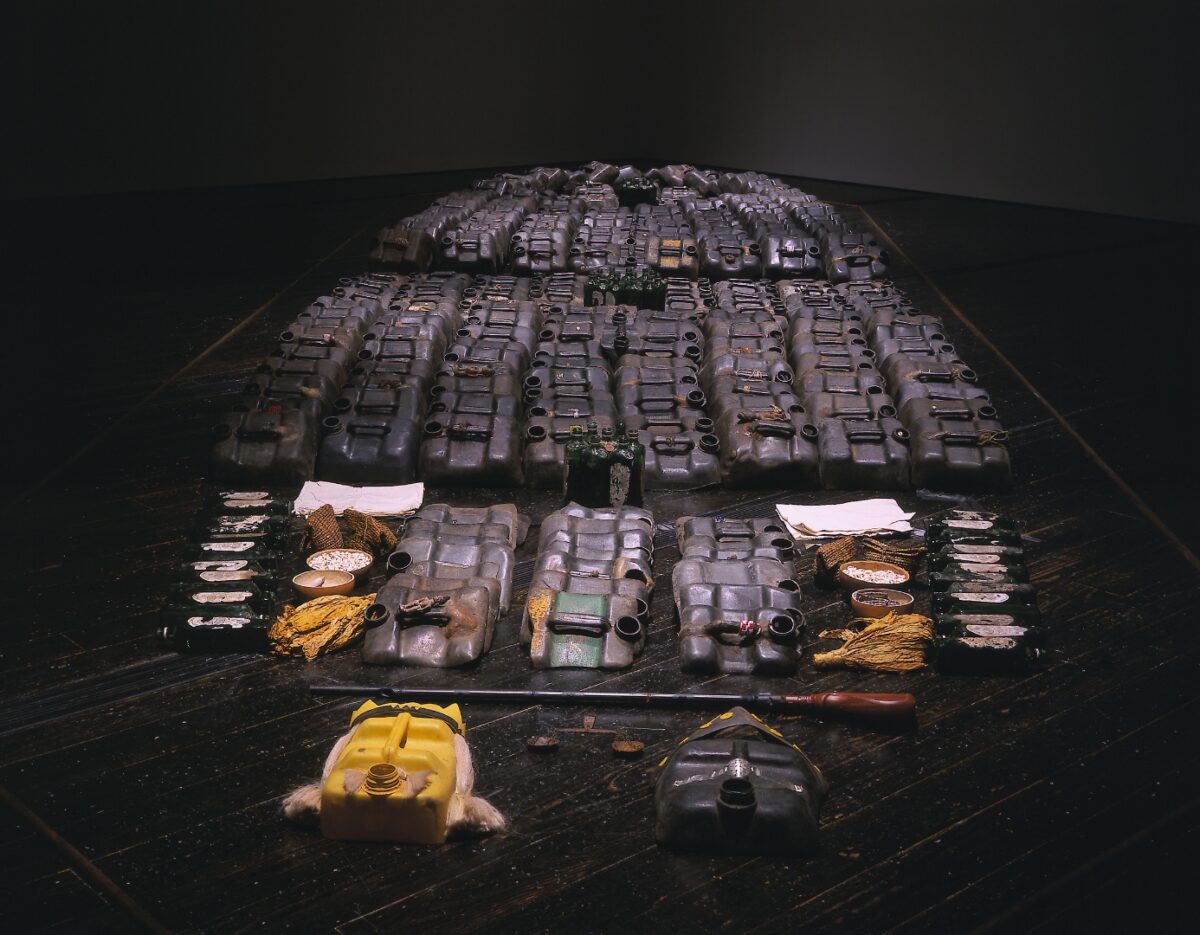

For example, in 1997, Hazoumè created his first well-known large-scale installation, La Bouche du roi (fig. 4).10La Bouche du roi was exhibited for the first time in Cotonou, Benin, in 1999 and later, among other exhibitions, in Romauld Hazoumé, Musée du quai Branly—Jacques Chirac, commissioned by Germain Viatte, September 12–November 13, 2006. The installation, under the curation of Dr. Chris Spring, was acquired by the British Museum and displayed there in 2007 to mark the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Held by the British Museum, this multimedia work is a tribute to the memory of slavery and the transatlantic trade that took place from the 17th to the 19th century between Dahomey, the Americas, and Europe.11Dahomey became the Republic of Benin in 1975 under Marxist dictator Mathieu Kérékou. The Republic of Benin should not be confused with the kingdom of Benin, a historical kingdom in what is now Nigeria. The mask-cans attached to the conscious or unconscious mind of their previous owners illustrate here the difficulty of obscuring the memory of slavery, as it is a deep-rooted history shared by African, European, and American people alike. Hazoumè’s artwork is a life-size representation of a slave ship containing 304 African slaves—each represented by a mask-can—who are crammed together in the ship’s hold. The artist based his reconstruction on the 1789 plans of the Brookes, a renowned British slave ship.12Christopher Spring, “Art, Resistance and Remembrance: A Bicentenary at the British Museum,” in Representing Enslavement and Abolition in Museums: Ambiguous Engagements, ed. Laurajane Smith et al. (Routledge, 2011), 193–211. At the front of the ship, two masks are arranged, set apart from the rest of the group by a rifle, emphasizing the violence associated with the trade. They represent the characters of Chacha de Souza (in yellow) and the king of the Kingdom of Dahomey, Adandozan (1797–1818), and/or his brother Ghézo (1818–1858; in black), upon whom he depended. Francisco Félix de Souza (1754–1849) was a major slave trader and the chacha, chief under the authority of the Dahomean king of the town of Ouidah, the hub of the Dahomean slave trade. Together, the king and the chacha were responsible for the slave trade: the king captured the slaves, while the chacha sold them to the Europeans. Both were responsible for transporting slaves to the Americas, and as a result, held the captain’s position at the bow of the ship La Bouche du roi. Through his installation, Hazoumè confronts this chapter in Beninese history. According to the artist, taking responsibility in the present for the future means understanding both culture and the past, however hard it may be.

Even if it tackles a historical subject, La Bouche du roi bears contemporary resonances as it evokes the smuggling of raw materials and goods as well as modern-day forms of forced labor. Looking at his work in the present time, Hazoumè connects it to the current treatment of sub-Saharan migrants in Libya or that of South Asian workers in the Gulf countries, even though he had not yet considered those issues in 1997.13Nima Elbagir et al., “People for sale: Where lives are auctioned for $400,” CNN, November 15, 2017, https://edition.cnn.com/2017/11/14/africa/libya-migrant-auctions/index.html.

In later works, such as Rat Singer, Second Only to God! (2013), the artist chose to address poor governance in modern nation-states. Rat Singer, Second Only to God! (fig. 5) depicts a pirogue sinking into a sea of mask-cans. On the boat’s deck, a white rat symbolizes the figure of the immoral ruler. The rat wears blinding dark glasses and is seemingly unaware of the disaster unfolding below. The work is a sarcastic political critique of the inaction of certain heads of state, especially dictators, regarding the issues that affect their citizens’ lives.

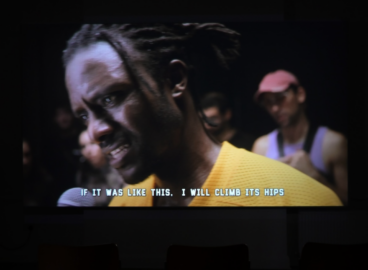

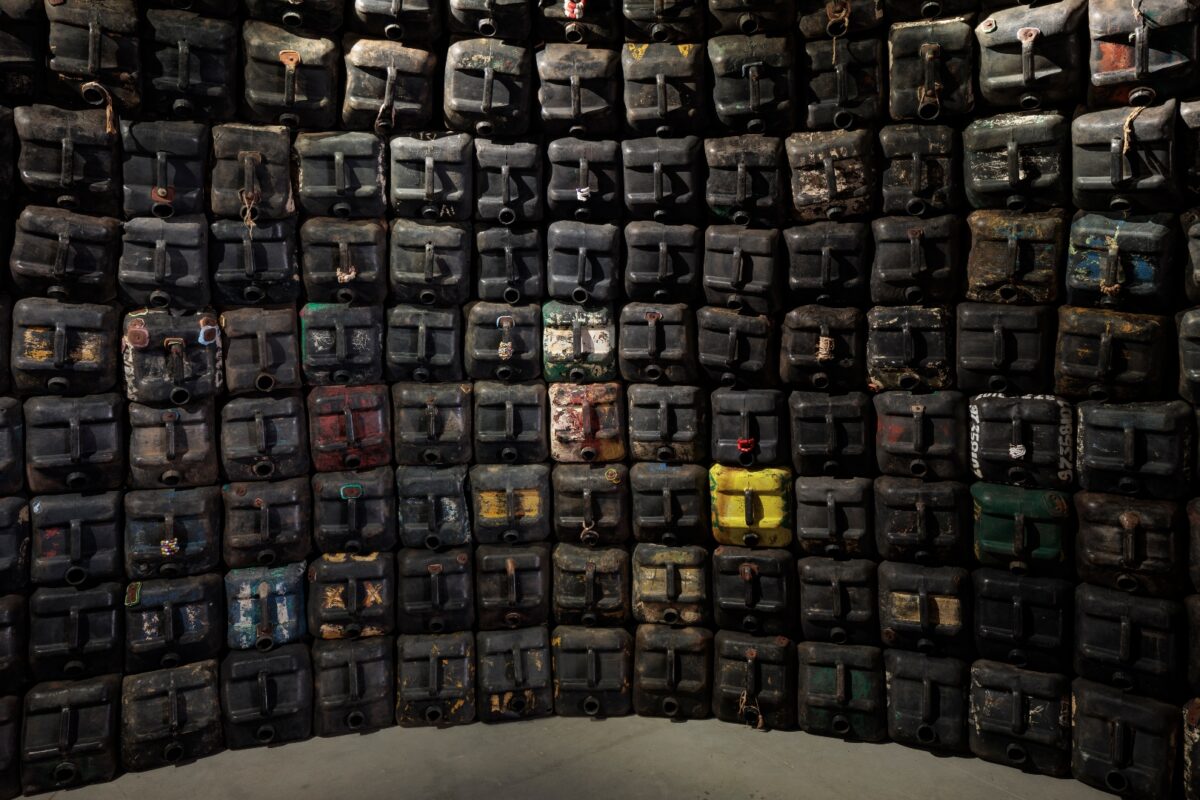

A more recent work, ASÈ (2024), created as part of Everything Precious Is Fragile, the first Republic of Benin pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, encapsulates the multiple threads in Hazoumè’s practice.14Everything Precious Is Fragile, Benin pavilion, curated by Azu Nwagbogu, 60th Venice Biennale, 2024. With the artists Romuald Hazoumè (born 1962), Ishola Akpo (born 1983), Moufouli Bello (born 1987), and Chloé Quenum (born 1983). See also Julia Hancart, “Everything Precious is Fragile: Donner à voir; Une ode à la fragilité,” Le Grand Tour, May 6, 2024, https://legrandtour-magazine.com/everything-precious-is-fragile/. This work is built with 540 plastic gasoline jerrycans to form a more than 13-foot-high hut with two opposing entrances (fig. 6). Smoothed on the outside using a process of plastic melting, the structure appears to have been built from raw earth, reminiscent of traditional architecture in Benin. Inside, the hundreds of colored mask-cans encircle and immerse the visitor in a meditative penumbra, barely illuminated by only a few beams of light (fig. 7). ASÈ was conceived as a sacred temple, reflecting the strong imprint of Voodoo religion on Beninese culture. During colonization, Voodoo was fought by Christian missionaries, and then it was banned by the Marxist regime of President Mathieu Kérékou in the 1970s.15Mathieu Kérékou (1933–2015) banned Voodoo in the 1970s. The end of his Marxist regime in 1990 coincided with the end of the USSR. Kérékou paved the way for a multiparty system and was defeated in the 1991 presidential elections by Nicéphore Soglo (born in 1934). Soglo inaugurated the Voodoo Festival on January 10, 1993. Despite these attempts throughout time and history, Voodoo has remained a part of Beninese culture. The artist thought of ASÈ as a space in which, upon entering, visitors could meditate, make a vow, and say “ASÈ,” which in Yoruba means “amen” and “so be it” but also “power.” The mask-cans functioned here as signifiers of the psychological connection between individuals and the Voodoo religion.

According to Hazoumè, there is power in returning to one’s history and culture, and ASÈ is his first installation entirely dedicated to traditional Beninese culture and speaks for it, fully embracing heritage as “a contemporary solution.” As the artist noted in 2024: “Today, our biggest problem as Africans is that we look at Europe, and we want to do what Europe does. But we can embrace our culture and be ourselves. When you talk about your own culture, you have a place in the world, which is not the case when you talk about someone else’s culture. Today we have to look at home.”16Hazoumè, interview, April 8, 2024.

A looping recorded recitation of a panegyric praising Tassin Hangbé, the warrior queen who ruled the Kingdom of Dahomey, now the Republic of Benin, from 1708 to 1711, highlights the significance of women’s role and power in Beninese society. Tassin Hangbé is recognized for having created the Amazons, also known as the Agodjé, an all-female military regiment that remained active until the end of the 19th century, when Dahomey was colonized. Through the Queen’s tale, the artwork presents an ode to women, echoing the Yoruba idiom “Iya Alachê” or “Iya ASÈ,” that is, “The woman has power.”

Romuald Hazoumè is an heir to the Beninese and Yoruba mask traditions, embracing both continuity and transformation. His work, which illustrates and critiques various historical and contemporary themes, is often also infused with a sense of humor or parody, drawing from the legacy of the Kaléta or Gélédé. In Hazoumè’s art, tradition and memory are not only preserved but also reimagined through everyday objects. By doing so, the Beninese artist positions himself as a guardian of memory and an actor in the formation of a new consciousness.

- 1Romuald Hazoumè, interview by the author, April 8, 2024.

- 2Romuald Hazoumè, interview by the author, March 23, 2025.

- 3Hazoumè, interview, March 23, 2025.

- 4Hazoumè, interview, March 23, 2025.

- 5Hazoumè, interview, March 23, 2025.

- 6See Yaëlle Biro, Fabriquer le regard: Marchands, réseaux et objets d’art africains à l’aube du XXe siècle (Les Presses du réel, 2018); John Warne Monroe, Metropolitan Fetish: African Sculpture and the Imperial French Invention of Primitive Art (Cornell University Press, 2019); and Maureen Murphy, De l’imaginaire au musée—Les arts d’Afrique à Paris et à New York (1931–2006) (Les Presses du réel, 2009).

- 7It is notable that artists have addressed these questions and others in diverse ways, including in the 1953 short documentary Les statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die) by Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Ghislain Cloquet. This film questions curatorial choices regarding the display of traditional African objects in French museums, serving as an anti-colonialist and anti-racist manifesto. His short documentary, commissioned by the magazine Présence africaine and released in 1953, was censored in France for 11 years due to its anti-colonial content. The 1970 short documentary You Hide Me by Ghanaian filmmaker Nii Kwate Owoo also addresses the issue of the thousands of objects looted from Ghana and Nigeria during the colonial conquests and then buried in storage in the basement of the British Museum.

- 8Following him, other artists have echoed his work, such as Dimitri Fagbohoun (born 1972), who is of Beninese and Ukrainian descent. In his quest to explore his diverse identities, Fagbohoun creates sculptures inspired by his research on traditional African statuary, particularly examples located in private and public collections in the West. Fagbohoun’s work involves reproducing masterpieces of classical African art in materials such as bronze, glazed ceramic, and wood. His aim is to renew a sense of majesty and to create new spaces and opportunities for reflection on the reappropriation of African heritage. Similarly, the artist Wole Lagunju (born Nigeria, 1966), appropriates the heritage of Gélédé Yoruba masks, blending them with Western aesthetic canons to critique colonialism.

- 9Hazoumè, interview, April 8, 2024.

- 10La Bouche du roi was exhibited for the first time in Cotonou, Benin, in 1999 and later, among other exhibitions, in Romauld Hazoumé, Musée du quai Branly—Jacques Chirac, commissioned by Germain Viatte, September 12–November 13, 2006. The installation, under the curation of Dr. Chris Spring, was acquired by the British Museum and displayed there in 2007 to mark the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade in 1807.

- 11Dahomey became the Republic of Benin in 1975 under Marxist dictator Mathieu Kérékou. The Republic of Benin should not be confused with the kingdom of Benin, a historical kingdom in what is now Nigeria.

- 12Christopher Spring, “Art, Resistance and Remembrance: A Bicentenary at the British Museum,” in Representing Enslavement and Abolition in Museums: Ambiguous Engagements, ed. Laurajane Smith et al. (Routledge, 2011), 193–211.

- 13Nima Elbagir et al., “People for sale: Where lives are auctioned for $400,” CNN, November 15, 2017, https://edition.cnn.com/2017/11/14/africa/libya-migrant-auctions/index.html.

- 14Everything Precious Is Fragile, Benin pavilion, curated by Azu Nwagbogu, 60th Venice Biennale, 2024. With the artists Romuald Hazoumè (born 1962), Ishola Akpo (born 1983), Moufouli Bello (born 1987), and Chloé Quenum (born 1983). See also Julia Hancart, “Everything Precious is Fragile: Donner à voir; Une ode à la fragilité,” Le Grand Tour, May 6, 2024, https://legrandtour-magazine.com/everything-precious-is-fragile/.

- 15Mathieu Kérékou (1933–2015) banned Voodoo in the 1970s. The end of his Marxist regime in 1990 coincided with the end of the USSR. Kérékou paved the way for a multiparty system and was defeated in the 1991 presidential elections by Nicéphore Soglo (born in 1934). Soglo inaugurated the Voodoo Festival on January 10, 1993.

- 16Hazoumè, interview, April 8, 2024.