From Matter to Data: Ecology of Infrastructures presents a selection of 15 film and video works that will be made available in three parts from July 29 till September 9. In this selection, which was available to watch from July 29 to August 12, artists reflect upon the role infrastructures of energy play in implementation of (geo)politics and emphasize the effects that exerts on the environment.

Energy: Ideology, Capital and Data

Environmental impacts are closely related to the modes of energy production and transport involving both the systems of supply of energy and pollution created by emissions. Construction of immense supply networks are often used to distribute capital and/or spread the ideology through instigation of alliances and interdependencies between countries and whole regions. A telling recent example is the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which is almost completed by Gazprom, has increased tension between Russia, the US, and Europe. The project linking Russia and Germany directly via the Baltic seabed would not only ensure Russia’s dominance of energy supplies to Europe, but also be ecologically harmful. However, most of the criticism facing the Nord Stream 2 project comes from a geopolitical, rather than an ecological perspective. The pipeline project presents itself as an environmentally friendly initiative that will help decrease carbon emissions from oil and coal, using ‘cleaner’ natural gas, but as the writer and filmmaker Oleksiy Radinsky mentions in his recent essay, it “would increase the structural, long-term dependency on fossil fuels to such an extent that a transition to a carbon-free economy—something that the Earth’s biosphere needs much earlier than we plan to institute—might actually never occur.”1Journal #107 – March 2020, Oleksiy Radynski – Is Data the New Gas?, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/107/322782/is-data-the-new-gas/

Energy Lithuania. 2018. Deimantas Narkevičius

To better understand the genealogy of the politics of energy in the region one should start by looking at the infrastructures from the socialist times. Deimantas Narkevičius’ Energy Lithuania (2000) is a portrait of the present of Elektrėnai, an industrial city that was erected by the Soviets in 1960 to support the newly built electric power station. Back in time, the city was presented as a symbol of modernization and drew people from different Soviet Republics to work there. The film mixes documentary footage from the Soviet era newsreels with newly shot observational material reflecting a long-term impact of ideology. Through interviews, the emphasis is put on the connection between subjective memories of the city’s inhabitants and the actual functioning of the power station. The lines between reality and illusion, documentary and fiction are intentionally blurred to make a statement about interconnections between social and environmental responsibility.

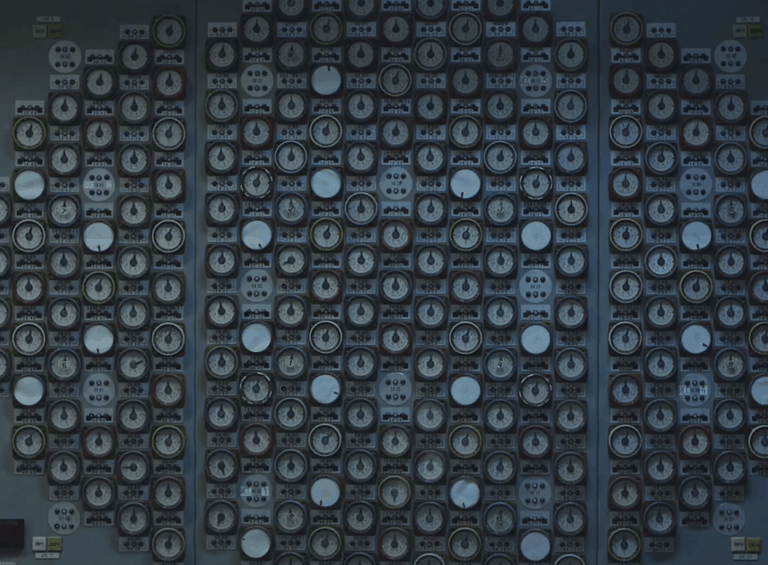

After Scarcity. 2018. Bahar Noorizadeh

Revealing a broader network of links between the economy, data and the energy politics of the socialist times, the sci-fi film essay After Scarcity (2018) by Bahar Noorizadeh focuses on Soviet cyberneticians (1950s – 1980s) and their attempt to build a fully-automated planned economy. How can one use computation towards new utopias? If history at its best is a blueprint for science-fiction, by revisiting contingent histories of economic technology After Scarcity enables a glance to the future. While the Stalinists opposed cybernetics, cyberneticians like Victor Glushkov rose to prominence in the 1960s as increasing bureaucratic demands of the centrally planned economy threatened to turn the Soviet Union into a highly administrative state. Networked computation held the promise of a new cyber-infrastructures and automated a national economy that would decentralize central planning. The flashing, affective light, hyper intense material sound and fast-paced screen text keep the spectator’s body on high alert. Advocating for the “other internet”, the film muses on the economic applications of socialist cybernetic experiments as an extraordinary comparison to financial arrangements and imaginaries of energy structures in capitalist countries.

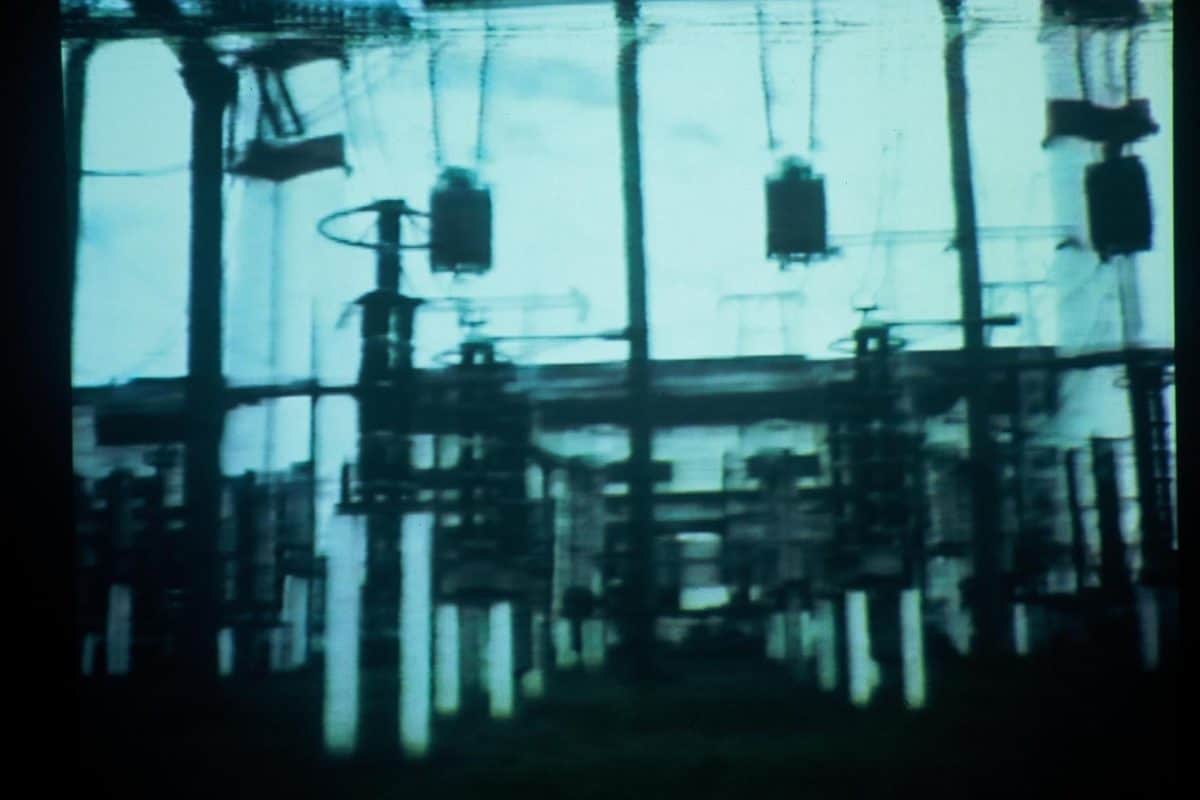

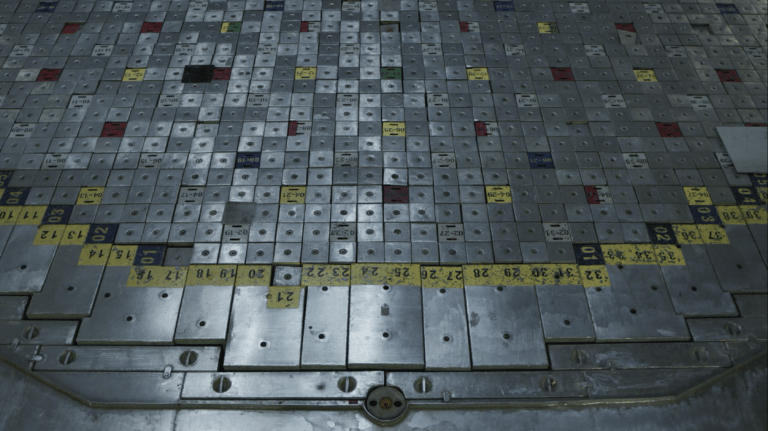

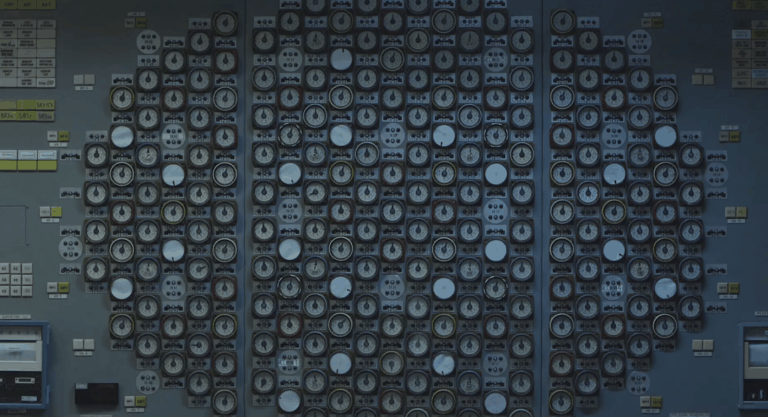

Energy Island. 2017. Emilija Škarnulytė

Energy Island (2017) by Emilija Škarnulytė takes us back to contemporary Lithuania via an immersive sensorial trip through the Soviet-built Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant, currently undergoing a politically and ecologically motivated decommissioning process. The images of contaminated ruins transform in the fire, light and shadow. The destruction of the huge infrastructure consistently reveals that the Cold War energy structures have impact on recent geopolitical processes and leave planetary threats over long periods of time. The project takes a geological approach, reading the elements that compose this flat landscape as a stack of stratigraphic layers. The human-made space is understood as a sedimentary process and the infrastructures, as well as the mineral resources, are assessed as the key parameters defining the development of the project. The second part of the film features a new energy structure — a sea carrier “Independence” designed as a floating liquefied natural gas storage and regasification unit. Built by Hyundai in South Korea, the vessel started operating in the autumn of 2014. It can store 6,000,000 cu ft of natural gas and can supply all of Lithuania’s need for natural gas providing some diversification of Lithuanian gas imports away from Russia. Almost tongue-in-cheek, the film compares the old energy structures to the new ones, erasing the dividing lines between the socialist and the capitalist logic of extraction and supply.

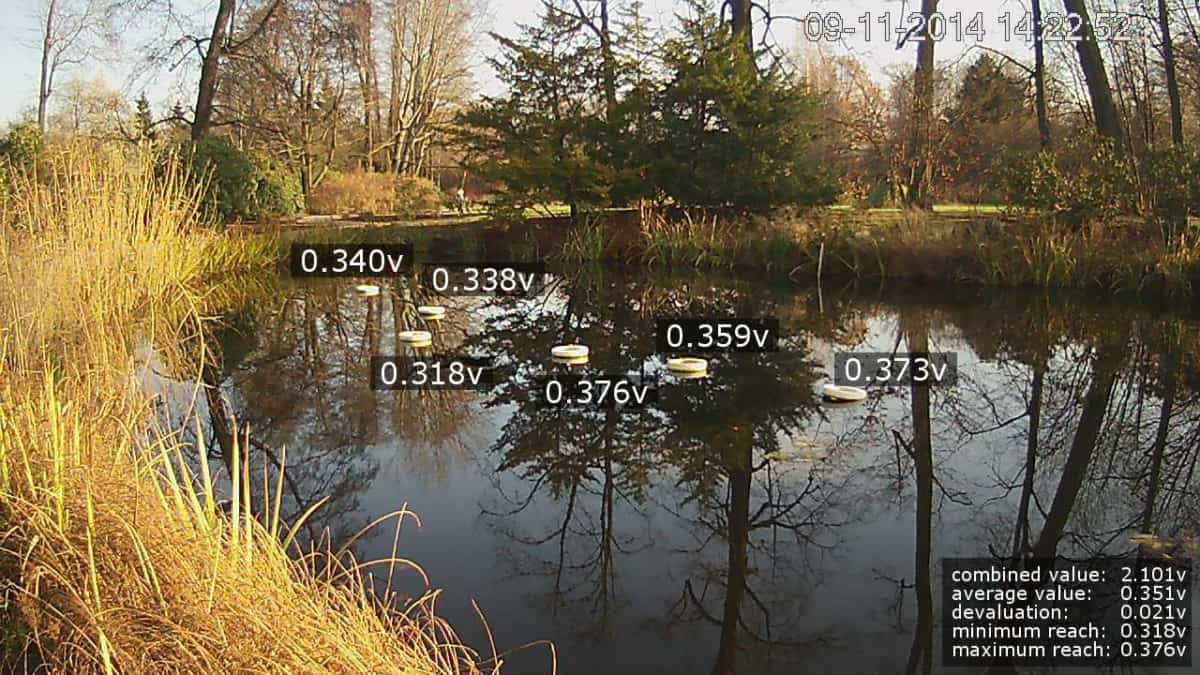

Pond Battery. 2015. Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits

Pond Battery (2015) by Rasa Smite and Raitis Smits visualizes more contemporary ways of energy production. The electric sound intervenes the seemingly idyllic landscape after the artists installed six microbial fuels in the pond of the Botanical Garden of the University of Latvia in Riga. Images of the measurements of bacteria’ electrical fluctuations were used to make the invisible activity visible and audible. A process of the generation of electricity was translated into live sound and image structures, providing an aesthetic perspective on the interaction between nature and technology, ecological systems and electronic networks, human and micro-worlds. The collected data from the seven-month long observation period is the footage and sound for the structural film and creates a sensual and emotional experience—a poetics of green energy.

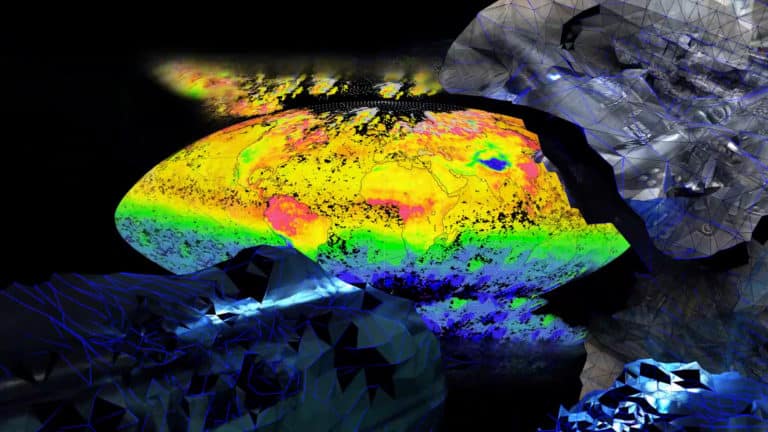

The Flood. 2018. Ivar Veermäe

Despite the emergence of new yet very rarely used possibilities for energy production, the ecological crisis pertains. The Flood (2018) by Ivar Veermäe touches upon the cryptocurrency mining that is inseparable from the environmental damage exerted by the intense use of electricity needed to carry out the process. The film is based on the footage shot in various cryptocurrency mines in Estonia combined with footage from Estonian oil shale mines. Virtual currency, such as Bitcoins, offer an attempt to withdraw from the existing financial system, because it offers the idea to release money production from the central bank’s control. Every utopian idea is inevitably accompanied by the risk that new centers or “bubbles” could arise. Small crypto mines are being replaced by increasingly bigger ones. Despite that some Estonian crypto mines are located in the territories of ex-power stations, this does a huge environmental damage because of the vast demand for energy needed to mine virtual currencies.

This film program is organized by Inga Lāce and Lukas Brasiskis in collaboration with the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, Lithuanian Culture Institute and Lithuanian Cultural Attaché in New York, Consulate General of Estonia in New York, Polish Institute, and Consulate General of the Slovak Republic in New York.

The second screening “Post Scriptum of Socialist Architecture” will be available from August 12 to August 26 and the last screening “Past’s Futures: Anthropocene or Capitalocene ” from August 26 to September 9, 2020.

- 1Journal #107 – March 2020, Oleksiy Radynski – Is Data the New Gas?, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/107/322782/is-data-the-new-gas/