A major new publication, Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology, presents key voices of this period that have been reevaluating the significance of the socialist legacy, making it an indispensable read on modern and contemporary art and theory. The publication offers a rich collection of texts and an additional, reexamining perspective to its 2002 sister publication, A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s, part of MoMA Primary Documents publications. For this new book, a series of conversations were commissioned with artists in the region and members of the C-MAP research group for Central and Eastern Europe at MoMA. The following is one of those dialogues, between Jon Hendriks and the artists Katalin Ladik and Tamás St.Auby.

Jon Hendricks: What were the conceptual bases of your work before 1989, both individually and together, and since 1989, both in Hungary and in exile?

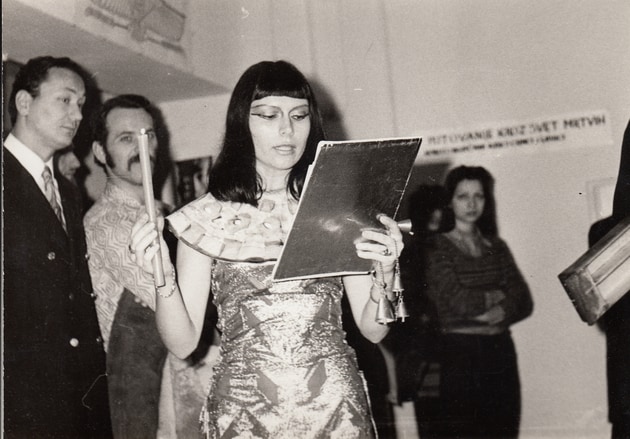

Katalin Ladik: All of my work has the same spiritual and intellectual roots, no matter in which historical period or country it has been created. In the multicultural and multinational Yugoslavia from the 1960s to the 1980s, artists enjoyed a fairly significant level of creative freedom. It was largely this multicultural environment that inspired my work. The political leadership of this period was to some extent lenient and tolerant toward the avant-garde forms of art. However, as a woman, I have experienced the oppressive and punitive measures and mechanisms of the Balkans’ male-chauvinist society and its cultural politics. I had to experience my own minority and inferior status at my workplace, in my artistic career, and in my personal life: what a man was allowed to do was considered unacceptable for a woman. Even so, I feel that we—Yugoslavian artists—enjoyed a greater creative freedom as compared to artists in Hungary. I left Yugoslavia in 1992 because of the Yugoslav wars. By that point Yugoslavia had ceased to exist; it had fallen apart to form smaller countries. My birthplace, Novi Sad, is now part of Serbia.

Tamás St.Auby: When I was a teenager in the late ’50s and showed my texts and images to my companions, I experienced envy from them sometimes. Their bad- mouthing could be shocking, but my pity on them was deeper, so since I was responsible for their sufferings, I tried to find a way to diminish the quality of my work while still being effective that wouldn’t incite others to break two of the Ten Commandments. This process drove me to the border of the Bad & Good, Prohibited & Free, Determinism & Free Will, Hierarchy & Anarchy, Church/State & Individual, Work & St.Rike, Object & Subject, Representation & Presentation, Art & Non-Art Art, Imitation & Action, Hell & Heaven, and all the dichotomies established by the given Mythical Status Quo. In the mid-’60s, the idea of [Joseph] Beuys, [George] Maciunas, and others about “everybody is an artist” proved to me that I’m not alone at the grassroots level. This conviction was in organic symbiosis with socialist/communist ideology, so I propagated Fluxus as Neo-Socialist-Realism, and established the International Parallel Union of Telecommunications in 1966, a Big Sister institution to counterbalance the power of the International Telecommunication Union, which controls the totality of the electromagnetic spectrum deeply into interstellar space as well. In an act of calumny, the Muscovite military-mercantile bureaucracy charged me with subversive activity connected to the CIA, imprisoned me, and then sent me into exile in 1974. In Switzerland, I continued without restrictions developing the Subsist.ence Level St.andard Project 1984 W. After the restoration of capitalism in the ex-Soviet bloc, I resettled in Hungary on June 16, 1991, the day of the withdrawal operation of the Red Army. I did not change my mind.

JH: From your perspective and geographic position, how did the shift in 1989 affect your art?

KL: My creative career and personal life were already influenced by political events before 1989. With Slobodan Milošević’s rise to power, toxic, destructive processes that blocked not only my own creative work but the activities of many other artists gained strength. As a result, many emigrated. I was especially immobilized by the punitive embargo against Yugoslavia. It was impossible to travel with a Yugoslavian passport. I received many invitations, but I was unable to participate in many international poetry events, art exhibitions, and performance festivals. For this reason, I was absent from the international art world for four or five years. Milošević’s dictatorship greatly hastened the processes leading to the breakup of Yugoslavia and the subsequent wars. Its cultural politics perverted artistic values. Hatred overcame society. I felt cut off; I was suffocating. In 1989, I was watching the “revolution” in Romania on TV. Even then, the “live feed” of the events felt like an absurd performance—as if Eugène Ionesco had written this “reality show.” I felt as if the balance and ethics of the world had turned upside down all around me. So I “fled ahead,” ahead of the war. I didn’t flee from the war, I fled ahead of it, to Hungary, in the hope that Hungary would not be overtaken by the psychosis of hatred. At that time, my son was studying in Budapest, at the music academy. I didn’t want a border between myself and my son; I wanted to be near him. I wished not to start over in Hungary but to continue with my creative career, which had been interrupted by the breakup of Yugoslavia. Even now, living in Hungary, my inspiration comes from my experiences in the late, multicultural Yugoslavia.

TS: No how. And I’m not an artist, but if I would be waterboarded in Guantanamo, I would confess to being a non-art artist.

JH: Has the post-1989 generation of artists referenced your earlier work?

KL: Yes. Quite a few references have been made, and there have been multiple theses written about my work, including my performances. I am always surprised that people are still interested in me. I wonder if it is possible that my past struggles remain relevant in this age. Is that why people care for my work? Do they still have to face the same issues I faced in the last century? If so, I am saddened by this.

TS: Sometimes in epigone exhibitions and by direct plagiarism.

JH: Do you feel as isolated from a new establishment over the past twenty-five years

as you did in the previous twenty-five?

KL: I have never felt isolated—not back then and not now. “Artistic solitude” is a prerequisite of art. When my work was finished—whether it be poetry, visual art, sound poetry, or performance—the audience, and society at large, reacted to it twenty-five years ago, and still does. I can sense that my art has an effect on people. This is the greatest evidence of not being isolated, not being alone.

TS: Partly yes, I feel isolated, because they haven’t arrested me yet, as if neither IPUT nor I exist, and partly no, I don’t feel isolated, because their legally paid museum directors, art historians, curators, journalists, and apparatchiks are committing calumnies against IPUT and its trust.ee in bankruptcy, me, as if IPUT and I do exist. And the state-run Hungarian Executive Penalty University of Fine Arts kicked me out of my job by envy and calumny, because I objected to the torturing and abusing of students and faculty and demanded Basic Democracy for all students and faculty.

JH: How do you see your past work from today’s perspective? Have your opinions of it changed? If so, how, and in what ways?

KL: My opinions haven’t changed; I still see my past work in the same way as always. My profile as an artist was shaped by both Yugoslavian—Central European— events in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, and my personal life. In my opinion, my work is the authentic result of the periods both before and after the regime change.

TS: I should have disseminated more bad images, more bad texts, videos, music, etc., to liberate those who are declared to be untalented by the Church and the State. And probably I should have organized more St.Rikes for Basic Democracy and Basic Income. But it is difficult in an environment where, contrary to Stanley Milgram, not only 83 percent of the people, but 83 percent of the 17 percent as well, are envious and calumnious, that is, break the ninth and tenth Commandments— authoritarian.

I AM RESPONSIBLE FOR ALL AND EVERYTHING! LONG LIVE BASIC INCOME!

LONG LIVE BASIC DEMOCRACY!

LONG LIVE ST.RIKE!

LONG LIVE CHELSEA MANNING!

Tamas St.Turba

(Trust.ee in bankruptcy of IPUT /International Parallel Union of Telecommunications/; Agent of NETRAF /Neo-Socialist. Realist. IPUT’s Global Counter Arthist.ory-Falsifiers Front/)