This essay charts the emergence of Colombo Art Biennale and Colomboscope in Sri Lanka, based on a talk that the author gave on February 10, 2018 at the panel “Writing Recent Exhibition Histories of Large Scale Recurring Exhibitions in South Asia” at the Dhaka Art Summit (DAS).

Opening its inaugural edition in 2012, DAS was born during a time when new biennale initiatives were sprouting across South Asia—starting in 2009 with the opening of the Colombo Art Biennale in Sri Lanka and the Kathmandu International Art Festival (now known as the Kathmandu Triennale), followed by the Kochi-Muziris Biennale which launched in India in late 2012. Early in the planning stages of DAS 2018, two new biennale initiatives were launched in Pakistan, the Karachi Biennale and the Lahore Biennale, which opened in 2017 and 2018, respectively. All of these biennale and festival-like initiatives came into being against extreme logistical barriers as a result of the deep investment and collaboration of the local arts communities of each context.

With an “all hands on deck” approach, there was little critical distance to be able to consider these initiatives from a local perspective given how embedded most arts professionals were in the creation of these institutions and exhibitions. Now that most of these biennales are over five years old, the panel “Writing Recent Exhibition Histories of Large Scale Recurring Exhibitions in South Asia” at DAS provided a forum for critics based in the region to evaluate these various initiatives and begin to chronicle recent exhibition history.

Who has been heard we know; they are the well-mapped islands, the rest are the unmappable sea of unheard, unrecorded humanity.

—Rebecca Solnit, A Short History of Silence, 2017

It is precisely as a “site of conflict” . . . that information can either be a place of repression or public resistance and that is where the possibilities of critique lie.

—Jorinde Seijdel, Information as a Site of Conflict and a Site of Critique, 2015

Context of Control

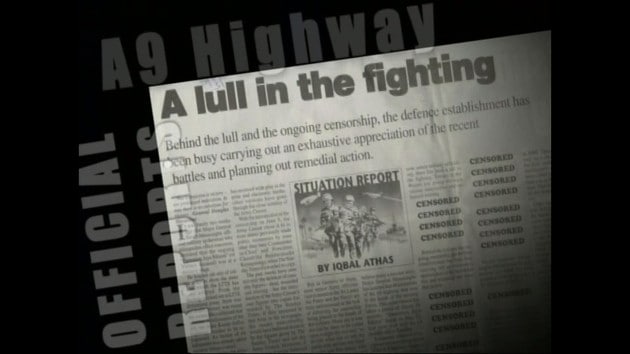

On May 14, 2000, Ruhanie Perera and Laila Nasry, two young Colombo-based journalists, published a story in the Sri Lanka Sunday Times titled “Attention or at ease.”1Ruhanie Perera and Laila Nasry, “Attention or at ease,” Sunday Times [Sri Lanka], May 14, 2000, http://www.sundaytimes.lk/000514/mirror2.html. It was meant to be a fairly straightforward survey of how youth in the capital feel about the latest round of wartime curfews and social restrictions. And yet to the journalists’ surprise, the article had to be sent to the Ministry of Information, along with every other piece on the war, to be reviewed and redacted. Those who worked at the national newspapers in the 1990s reveal not only that this was the regular procedure at times—but also that editors would purposely choose to print their publications with the blacked-out areas included.

The years that followed, in particular 2005–15, are said to have been some of the worst for press censorship in Sri Lanka. In a recent article posted on the alternative media site Groundviews, journalist Daisy Perry discusses the “systemic application of pain inflicted on the media” in Sri Lanka during this period.2In this article journalist Daisy Perry quotes the author Achille Mbembe and discusses his book of essays On the Postcolony (2001) in relation to Sri Lanka, https://groundviews.org/2017/12/14/conviviality-vs-censorship-on-media-freedom-in-sri-lanka/. What’s interesting about evoking the notion of pain is that it, like repression, is most often invisible. Chronic states of pain and repression also share the common side effect of shrinking one’s sense of self. The decision to print these stories punctuated by their deletions is indicative of a pushback against this shrinkage, of rendering the censorship visible. It’s a small tale of defiance if you will.3This statement is a reference to the 2018 exhibition One Hundred Thousand Small Tales, curated by Sharmini Pereira at the fourth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit, where this paper was first presented.

This poignant image of control serves as a visual reminder (especially in a post-2015 era of relative openness in the press under the new government) of the strategies long employed to circumvent being silenced, and of the extended climate of constraint within which many contemporary art exhibitions in Sri Lanka have taken place. Both during and after the war, many artists—though not the main targets of state surveillance unless they were also activists—chose to band together, to practice in “safe spaces,” to self-censor, and/or to go underground. At the same time, several art exhibitions of provocative and political work were staged, at the National Art Gallery, Lionel Wendt Art Gallery, and Jaffna Public Library.4This includes, among several others, the Young Contemporaries series by the George Keyt Foundation; New Approaches in Contemporary Sri Lankan Art (1994), curated by Sharmini Pereira at the National Art Gallery; Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s annual exhibition to mark the July 1983 riots, staged from 1997 onward first at the Heritage Gallery and then later at the Lionel Wendt Gallery; and Aham Puram (2004) at the Jaffna Public Library.

It is important to remember that some of these initial contemporary art exhibitions, which took place in Sri Lanka from the mid-1990s to 2000s, were mounted in response to the multiple political crises of the time, including the violent uprisings by the Marxist-Leninist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna in the south of the island (1971–79 and 1987–89), and the devastating civil war between government forces and Tamil separatists, which took place largely in the north and the east of Sri Lanka (1983–2009). Much of the work produced and exhibited at the Vibhavi Academy of Fine Arts, started by Chandraguptha Thenuwara in 1996, and Theertha International Artists’ Collective, co-founded by Jagath Weerasinghe and Anoli Perera in 2000, was also reflective of these complex and overlapping sociopolitical currents.

Puncturing and Resonance

This active, intense, and variegated historical context helps us to understand that the artistic responses to the twenty-seven-year civil war and its different political phases were not homogenous—and that the boundary between conflict and post-conflict was not definitive. In fact, the first edition of the Colombo Art Biennale (CAB) was conceived during the height of the war, in February 2009, but mounted just four months after the conflict came to a bloody and violent end in September 2009. Gallerist Annoushka Hempel, director and co-founder of the biennale, reminds us that artist and co-founder Jagath Weerasinghe’s decision to title the exhibition Imagining Peace in the most acute and chaotic stage of the conflict was both speculative and subversive.

Though its charged and checkered nature can be seen as an extension of what came before (especially as most of the works in the exhibition were reflective of war and not of peace), its collaborative aspect was novel. Six of Colombo’s key cultural practitioners—Chandraguptha Thenuwara, Jagath Weerasinghe, Saskia Fernando, Nazreen Sansoni, Chaminda Gamage, and Annoushka Hempel—each of whom curated a “pavilion,” worked together. Fernando recalls that the opportunity for artists to produce large-scale, noncommercial works was also refreshing. She curated Jagath Ravindra’s Inside Out (2009), an installation of sculptural heads surrounded by scores of bullets suspended in the air, next to a poem written for the event by Groundviews editor Sanjana Hattotuwa.5See Sanjana Hattotuwa, “Imagining Peace,” https://sanjanah.wordpress.com/2009/09/03/imagining-peace-2/.

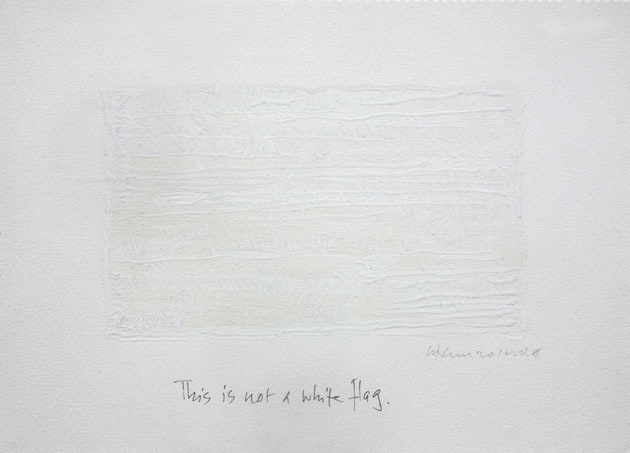

Nearly three years later, in 2012, Hempel mounted the next edition of CAB, titled Becoming, which she still describes as the most sensitive to date: “Press censorship was at its worst then and the biennale acted as a form of reportage in a way.”6As told to the author in an interview that took place in January 2018. Referencing the discrepancies in state narratives around the final stages of the war, Thenuwara created a controversial series of works titled This is not a white flag (2012) especially for this edition.7Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s series This Is Not a White Flag (2012) questions the very idea of peace and also references a moment during the final stage of the war, when white flags were supposed to have been raised. For a fuller description, see Gunvanthi Balaram, “These Are Not White Flags—The Indian Express, Sun Mar 22 2012,” artaholicblogdotcom, http://colomboartbiennale.com/blog/2012/04/03/these-are-not-white-flags-the-indian-express-sun-mar-11-2012/. Those who attended the talks panel—launched that year as part of an extended event with two international curators (Suresh Jayaram and Roman Berka) and more venues—described them as “gutsy”. Contrarily, one audience member asked why there were not any artworks “celebrating” the end of the war.8As told to the author in an interview that took place in January 2018.

Challenging post-conflict questions were beginning to crop up, and in 2013—to fill the void of the Galle Literary Festival9The Galle Literary Festival was set up in 2007 and takes place in Galle, Sri Lanka, about an hour and a half from Colombo. The event usually includes a number of well-attended public discussions with local as well as international authors. hiatus—the first Colomboscope arts festival was created as a public space for expression.10Colomboscope changed its name to Standard Chartered Colomboscope in 2014 and then to Cinnamon Colomboscope in 2015, after the Cinnamon Hotels and Resorts became title sponsor. Initiated by the Goethe Institut and curated by author Ashok Ferrey, its inaugural edition was titled Identities and it had literary, film and art components—such as Ruhanie Perera’s performance piece Somewhere between Truth and Its Telling (2012) about the trauma of displacement faced by women during the war.11Somewhere Between Truth and Its Telling (2012) was performed independently by Perera in previous iterations. This iteration, titled Absence (2013), was a Floating Space production in which Perera’s performance art piece (now performed as a scene in the work) looked at the idea of unmaking a character, of stripping her down until she was an outline of herself with her face disfigured by grief. At its core was the talks program, which posed critical counter-narratives, such as asking representatives from the media and the Sri Lankan army, “Who counted the bodies?,” and clergymen in a time of increasing polarization what religion means to them in “My Life in Robes.”

Amplification and Splitting

Some commentators suggested that perhaps Identities was more radical and experimental than other festivals that followed as it was the first edition, and it had fewer sponsors. In comparison, by this point, CAB was working toward its third edition. Registered as a private company, its organizers were reaching out to corporate and state sponsors in a bid to develop a larger, more diverse platform. For their 2014 outings, CAB and Colomboscope decided to open together and share a theme and the title Making Histories, for which the former would provide the art and the latter the talks. However, due to a number of points of divergence, including in their sponsorships and curatorial directions, the two ended up being disparate events.

CAB 2014, curated in part by Amit Kumar Jain, aimed to showcase new, younger artists, perhaps in response to the fact that many of the same artists had repeatedly been shown in previous editions. Logistical and funding issues, however, resulted in a multi-part, haphazard exhibition that lacked conceptual focus and depth.12For a full review of the Colombo Art Biennale 2014, see Jyoti Dhar, “Colombo Art Biennale: Making History,” ArtAsiaPacific 88 (May/Jun 2014), https://s3.amazonaws.com/externalclips/1444901/88Reviews-Colombo_p159.pdf?1444977273. Exceptions include Herstories (2014) by Radhika Hettiarachchi, a poignant archival project mapping mothers’ stories.13This iteration of “Herstories” by Radhika Hettiarachchi, which maps the stories of mothers from north, south, and east Sri Lanka, was presented along with Shanika Perera’s graphic illustrations. See http://herstoryarchive.org/exhibitions/colombo-art-biennale-2014/. Hettiarachchi also curated Colomboscope that year, a “think-fest” of film, music, and uninhibited discussion. While talks took place in the Whist Bungalow, Old Town Hall, and Grand Oriental Hotel, Paraya (2014), an interactive play directed by Arun Welandawe-Prematilleke, was staged at the old Rio Cinema.14Paraya (2014), a Mind Adventures Theatre Company production, is a well-received and hard-hitting play that critiques issues such as state apathy and public compliance. To read a full review, see Gehan Gunatilleke, “The Politics of Paraya,” Groundviews, September 24, 2013, http://groundviews.org/2013/09/24/the-politics-of-paraya/.

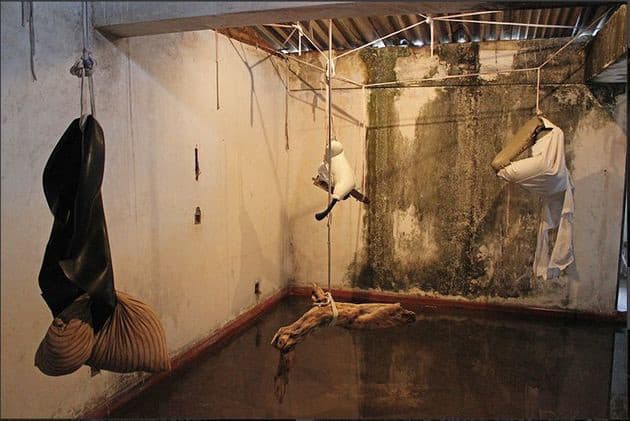

Along with “memory walks” with historians, this edition set the tone for Colomboscope to become about reclaiming histories and spaces. After seeing Paraya, co-curators Natasha Ginwala and Menika van der Poorten mounted the next edition, titled Shadow Scenes (2015), at the Rio Cinema and Hotel in Slave Island (Kompanna Veediya), a site and neighborhood laden with violent memories and current complexities. Its curatorial strength lay in its contextually sensitive works by Jaffna and Colombo-based artists such as Mahen Perera, who contributed an abattoir-like installation.15To see a fuller selection of works on display at Colomboscope 2015, see Jyoti Dhar, “Field Trip: Cinnamon Colomboscope 2015,” ArtAsiaPacific blog, August 28, 2015, http://artasiapacific.com/Blog/FieldTripCinnamonCol Notably, Shadow Scenes and its strong but separate talks program The City.Identity.Urbanity. were set within a renewed sense of openness and optimism, six months after the new government had come into power.16Kacha Kacha, a local music and rap night of “uncensored expression,” was launched at the Castle Hotel as part of this edition of Colomboscope’s talks program.

Projection and Noise

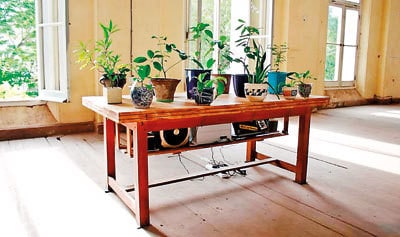

By 2015 several palpable shifts were taking place in the city. Beyond initial postwar development and disturbances, many cultural practitioners were now looking at what forms truth and reconciliation might take. An expanded Colomboscope, under new sponsorship, also pivoted, to the forward-looking theme “Art and Digital Cultures in South Asia and Europe.” However, this time a local counterpart could not be found to complement the international curator, Susanne Jaschko, and the resultant exhibition Testing Grounds (2016) came across as rather didactic and disconnected from local realities.17For full review of Colomboscope 2016, see Jyoti Dhar, “Art as a Place—From here on,” Sunday Times [Sri Lanka], September 25, 2016, http://www.sundaytimes.lk/160925/plus/art-as-a-place-from-here-on-209348.html. Staged in the old General Post Office, the art, such as CoCA’s music-producing plants Emerge+Tech (2016), took precedence over supplementary talks.18Emerge + Tech (2016) by the Collective of Contemporary Artists (CoCA) was a musical sculpture made up of myth- and medicine-associated plants that emit high-pitched xylophonic notes when touched.

Similar issues regarding the underlying structure of the festival seemed to plague CAB. Some local curators distanced themselves, with one citing the event’s lack of clarity and direction as a reason.19.As told to the author by four different cultural practitioners, who wish to remain anonymous, in separate interviews conducted in January 2018. Nevertheless, Conceiving Space (2016), curated by Alnoor Mitha, was the biennale’s largest and most even rendering to date, with works such as Rajni Perera’s site-specific installation A Long Arm, A Tight Grip (2016) beginning to engage with layered histories.20Rajni Perera created the site-specific sculptural installation A Long Arm, a Tight Grip for the Colombo Art Biennale 2016 and said in a curatorial tour, which I attended, that it was meant to be “a theatrical critique of the aftermath of colonial rule, which still exists to this day.” On the other hand, the architecture and community aspect also launched this edition, curated by Gihan Karunaratne (in particular, The Great Feast along Dispensary Lane) were uneven at best and problematic at worst in their framing of and insensitivity toward local culture.21For full review of Colombo Art Biennale 2016, see Jyoti Dhar, “Art as a place: Canvas of germination and growth,” Sunday Times [Sri Lanka], December 25, 2016, http://www.sundaytimes.lk/161225/plus/art-as-a-place-canvas-of-germination-and-growth-221240.html.

It’s fair to say that somewhere in their drive to be bigger and better, these festivals lost their charge and, to a certain extent, their way. It’s also important to remember that in this transitional political and economic space, between hope, apathy, and resolution, some artists were questioning and reassessing their practices. “Now we don’t know what we’re reacting to,” said van der Poorten,22As told to the author in an interview that took place in January 2018. who curated the most recent iteration of Colomboscope. Set in the former Colombo Terminus Railway Station, Re(evolution) (2017) aimed to engage with environmental concerns. However, time and sponsorship issues resulted in a hasty assortment of works. Exceptions included Ruwangi Amarasinghe’s Medusozoa Siri Siri (2017), a ghostly installation of jellyfish made out of refuse.23Ruwangi Amarasinghe’s work Medusozoa Siri Siriused plastic bags gathered during the relief effort for the Meethotamulla garbage dump disaster and upcycled them into an eerie installation of mock-jellyfish, critiquing both water and waste pollution in Sri Lanka.

As usual, the talks generated some interesting questions—this time around major development projects in Sri Lanka, including Megapolis, Uma Oya, and Colombo Port City. In this sense, Colomboscope has retained its rootedness in local contexts, shifts, and audiences. However, both festivals have been accused of catering primarily to the English-speaking elite of Colombo and need to address this if they are to have continued relevance.24In a conversation with Jagath Weerasinghe in January 2018, originally one of the co-founders of the biennale, he spoke to me of how exclusive the event has become over the years. In addition, organizers have recognized the need to curate and collaborate in more sustainable ways. As part of this effort, CAB hopes to change its structure from that of a private company to that of a nonprofit foundation, and Colomboscope is being restructured as an independent organization.

Recording Histories

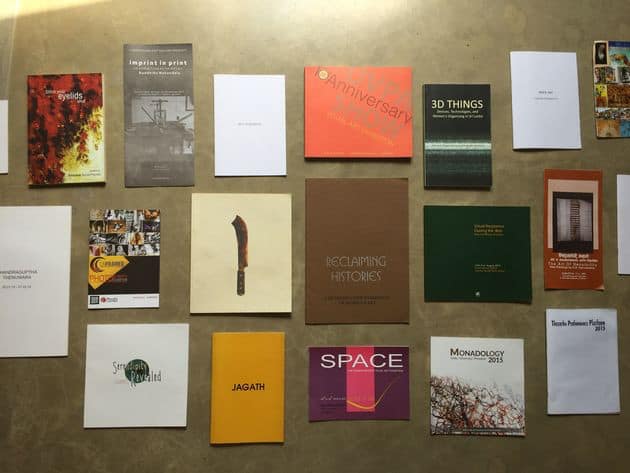

Looking back at these exhibition histories, one could somewhat summarize and see that the arc they have taken extends from unearthing and engaging with the past to gazing and leap-frogging into the future. However, the need to stand still, not only to critique the present, but also to engage in a more considered and rigorous reading of the moment, is vital. While CAB and Colomboscope have certainly provided frameworks for encounter and visibility, the majority of the most interesting art practices still takes place outside of these institutions—in homes, studios, and informal spaces as well as in smaller-scale festivals and exhibitions throughout the year.25Examples of these include Theertha Performance Platform 2015, Wings Festival 2016, Human Rights Festival 2017, gatherings at Mullegama Art Centre, Em-(body)-ing Power (2018) at the Sapumal Foundation, and several exhibitions at Saskia Fernando Gallery and Barefoot Gallery.

At one such recent exhibition of photography reflective of postwar concerns, called Unframed (2018), the executive director of the Centre for Policy Alternatives spoke to a gathering of artists, journalists, and students about the way in which history is recorded. He said that as Sri Lanka approaches ten years since the end of the war and seventy years of independence, the need for acknowledgment and accountability is of the essence, otherwise the country will in one way or another always be at war with itself.26This was said at the opening of Unframed at J. D. A. Perera Gallery in Colombo, which I attended on January 30, 2018. Historically, one of the key ways in which this has been done in Sri Lanka is through alternative media and the arts. For this reason, more than any other, it is crucial that these sites for counter-information and expression continue to take root, sprout, and grow into many different forms.

- 1Ruhanie Perera and Laila Nasry, “Attention or at ease,” Sunday Times [Sri Lanka], May 14, 2000, http://www.sundaytimes.lk/000514/mirror2.html.

- 2In this article journalist Daisy Perry quotes the author Achille Mbembe and discusses his book of essays On the Postcolony (2001) in relation to Sri Lanka, https://groundviews.org/2017/12/14/conviviality-vs-censorship-on-media-freedom-in-sri-lanka/.

- 3This statement is a reference to the 2018 exhibition One Hundred Thousand Small Tales, curated by Sharmini Pereira at the fourth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit, where this paper was first presented.

- 4This includes, among several others, the Young Contemporaries series by the George Keyt Foundation; New Approaches in Contemporary Sri Lankan Art (1994), curated by Sharmini Pereira at the National Art Gallery; Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s annual exhibition to mark the July 1983 riots, staged from 1997 onward first at the Heritage Gallery and then later at the Lionel Wendt Gallery; and Aham Puram (2004) at the Jaffna Public Library.

- 5See Sanjana Hattotuwa, “Imagining Peace,” https://sanjanah.wordpress.com/2009/09/03/imagining-peace-2/.

- 6As told to the author in an interview that took place in January 2018.

- 7Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s series This Is Not a White Flag (2012) questions the very idea of peace and also references a moment during the final stage of the war, when white flags were supposed to have been raised. For a fuller description, see Gunvanthi Balaram, “These Are Not White Flags—The Indian Express, Sun Mar 22 2012,” artaholicblogdotcom, http://colomboartbiennale.com/blog/2012/04/03/these-are-not-white-flags-the-indian-express-sun-mar-11-2012/.

- 8As told to the author in an interview that took place in January 2018.

- 9The Galle Literary Festival was set up in 2007 and takes place in Galle, Sri Lanka, about an hour and a half from Colombo. The event usually includes a number of well-attended public discussions with local as well as international authors.

- 10Colomboscope changed its name to Standard Chartered Colomboscope in 2014 and then to Cinnamon Colomboscope in 2015, after the Cinnamon Hotels and Resorts became title sponsor.

- 11Somewhere Between Truth and Its Telling (2012) was performed independently by Perera in previous iterations. This iteration, titled Absence (2013), was a Floating Space production in which Perera’s performance art piece (now performed as a scene in the work) looked at the idea of unmaking a character, of stripping her down until she was an outline of herself with her face disfigured by grief.

- 12For a full review of the Colombo Art Biennale 2014, see Jyoti Dhar, “Colombo Art Biennale: Making History,” ArtAsiaPacific 88 (May/Jun 2014), https://s3.amazonaws.com/externalclips/1444901/88Reviews-Colombo_p159.pdf?1444977273.

- 13This iteration of “Herstories” by Radhika Hettiarachchi, which maps the stories of mothers from north, south, and east Sri Lanka, was presented along with Shanika Perera’s graphic illustrations. See http://herstoryarchive.org/exhibitions/colombo-art-biennale-2014/.

- 14Paraya (2014), a Mind Adventures Theatre Company production, is a well-received and hard-hitting play that critiques issues such as state apathy and public compliance. To read a full review, see Gehan Gunatilleke, “The Politics of Paraya,” Groundviews, September 24, 2013, http://groundviews.org/2013/09/24/the-politics-of-paraya/.

- 15To see a fuller selection of works on display at Colomboscope 2015, see Jyoti Dhar, “Field Trip: Cinnamon Colomboscope 2015,” ArtAsiaPacific blog, August 28, 2015, http://artasiapacific.com/Blog/FieldTripCinnamonCol

- 16Kacha Kacha, a local music and rap night of “uncensored expression,” was launched at the Castle Hotel as part of this edition of Colomboscope’s talks program.

- 17For full review of Colomboscope 2016, see Jyoti Dhar, “Art as a Place—From here on,” Sunday Times [Sri Lanka], September 25, 2016, http://www.sundaytimes.lk/160925/plus/art-as-a-place-from-here-on-209348.html.

- 18Emerge + Tech (2016) by the Collective of Contemporary Artists (CoCA) was a musical sculpture made up of myth- and medicine-associated plants that emit high-pitched xylophonic notes when touched.

- 19.As told to the author by four different cultural practitioners, who wish to remain anonymous, in separate interviews conducted in January 2018.

- 20Rajni Perera created the site-specific sculptural installation A Long Arm, a Tight Grip for the Colombo Art Biennale 2016 and said in a curatorial tour, which I attended, that it was meant to be “a theatrical critique of the aftermath of colonial rule, which still exists to this day.”

- 21For full review of Colombo Art Biennale 2016, see Jyoti Dhar, “Art as a place: Canvas of germination and growth,” Sunday Times [Sri Lanka], December 25, 2016, http://www.sundaytimes.lk/161225/plus/art-as-a-place-canvas-of-germination-and-growth-221240.html.

- 22As told to the author in an interview that took place in January 2018.

- 23Ruwangi Amarasinghe’s work Medusozoa Siri Siriused plastic bags gathered during the relief effort for the Meethotamulla garbage dump disaster and upcycled them into an eerie installation of mock-jellyfish, critiquing both water and waste pollution in Sri Lanka.

- 24In a conversation with Jagath Weerasinghe in January 2018, originally one of the co-founders of the biennale, he spoke to me of how exclusive the event has become over the years.

- 25Examples of these include Theertha Performance Platform 2015, Wings Festival 2016, Human Rights Festival 2017, gatherings at Mullegama Art Centre, Em-(body)-ing Power (2018) at the Sapumal Foundation, and several exhibitions at Saskia Fernando Gallery and Barefoot Gallery.

- 26This was said at the opening of Unframed at J. D. A. Perera Gallery in Colombo, which I attended on January 30, 2018.