Writer Gyula Muskovics looks at the Georgian avant-garde fashion scene from the postcommunist transition, which began in 1991, to the present. He sets out by giving a few examples of how traditional values are called into question in the experimental collections of young designers while briefly describing the social reality giving rise to their queer fantasies. He then shows that despite the implications of the recent trend to refer to this generation of artists as rootless, there is a rich history to be discovered. Based on interviews and rarely seen archival footage, he gives insight into Tbilisi’s avant-garde fashion circles in the 1990s with a special focus on the Avant-garde Fashion Assembly.

A Rootless Generation?

The end of the 2010s saw the emergence of post-Soviet fashion, which drew inspiration from the Eastern European vibe—or, perhaps, the Western fantasies of it. Many have already described the global tendencies that have heightened interest in the cultural landscapes of the former communist bloc—from the capitalist market crash in 2008 to the events in Kyiv’s Maidan Square in 2014.1For a summary see, Gyula Muskovics, “What Is Not New in the ‘New East’?—Post-Soviet Fashion and the 1980s,” East Art Mags, posted October 13, 2019, https://artportal.hu/magazin/what-is-not-new-in-the-new-east-post-soviet-fashion-and-the-1980s/. It is remarkable, however, that post-Soviet fashion, while feeding the commercialization of the fashion industry and producing labels like “New East” that imply the rootlessness of the current generation, has given international visibility to the region’s lesser-known creative scenes.2See, for example, Anastasiia Fedorova, “Post-Soviet Fashion: Identity, History and the Trend that Changed the Industry,” Calvert Journal, posted February 23, 2018, https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/9685/post-soviet-visions-fashion-aesthetics-gosha-demna-lotta-vetements.

This article takes a closer look at the art and fashion community in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, introducing designers and artists who in their analysis of the post-Soviet condition move beyond the surface (beyond, for example, Lenin’s bust, the red star, the hammer and sickle, etc.) to examine the challenges specific to the society in which they live. Among the issues that countercultural efforts in the South Caucasian country have responded to since Georgia’s break from the Soviet Union in 1991—as Vija Skangale suggests in a recent article for post3See Vija Skangale, “An Underground Bridge to Georgian Collectiveness: Finding a Tribe through Collective Trauma,” post: notes on art in a global context, posted July 15, 2022, https://post.moma.org/an-underground-bridge-to-georgian-collectiveness-finding-a-tribe-through-collective-trauma/.—are homophobia and discrimination against the LGBT+ community. Therefore, my text focuses on how fashion, especially the more experimental, avant-garde endeavors from the postcommunist transition in the 1990s to the present, has become a platform for queer sensibilities.

Queering the Catwalk

In talking about fashion in Georgia, the biannual Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Tbilisi (MBFT) is unavoidable.4The Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Tbilisi was founded in 2015 by Sofia Tchkonia. The fact that Demna [Gvasalia] (born 1981), who is now creative director of Balenciaga, and other designers such as George Keburia (born 1990) or Irakli Rusadze (born 1991) of Situationist, have also made their way to the epicenter of the fashion world has a lot to do with Tchkonia’s work. The MBFT, in addition to helping local designers establish themselves internationally, offers the youngest generation a great space for experimentation. It has also played a role in shifting the focus from marketability to artistic vision and presentation, bringing the avant-garde trends of the 1990s to fashion.

Akà Prodiàshvili (born 1995), one of those young fashion designers who moves beyond the binary, made his MBFT debut in 2018 with his spring/summer 2019 collection, which drew inspiration from drag culture and cross-dressing. Although discrimination against LGBT+ people is forbidden by law in Georgia, members of the community still face attacks. Prodiàshvili has stepped out of heteronormative reality in different ways and transformed this pain into energy and protest.5See Liana Satenstein, “In Georgia, One Young Designer Is Bringing Drag to the Runway,” Vogue, posted November 12, 2018, https://www.vogue.com/article/aka-prodiashvili-tbilisi-fashion-week-drag-rupauls-drag-race. Similarly, fashion designer Levau Shvelidze (born 1996) utilizes his work as a form of activism in order to make his experience of Tbilisi more visible to the conservative society within Georgia.6Nino Sichinava, “Meet Levau Shvelidze the Eccentric and Self-Declaring Designer You Should Know,” Fucking Young, posted April 21, 2022, https://fuckingyoung.es/meet-levau-shvelidze-the-eccentric-and-self-declaring-designer-you-should-know/. His grotesque and gender-fluid works of art are sometimes inspired by folk tales and the artist’s pink, bloody nightmares and, at other times, by anime, eco-horror, metaverse, 3D art, and sexual fetishes. While sustainability and upcycling are important to Shvelidze, ethical fashion’s most notable representative in this generation is Nini Goderidze (aka God Era; born 1997), who recently created biodegradable vegan leather. In her work, which ranges from fashion and costume design to installation, she sees the body as an “object and inspiration for developing an organic art medium.”7Liana Satenstein, “Tbilisi’s Most Photographed Street Style Star Accessorizes with Plastic Dolls,” Vogue, posted November 9, 2018, https://www.vogue.com/article/nini-goderigidze-tbilisi-street-style-star. In God Era’s technologically queered, futuristic universe, humans are genderless cyborgs, hybrids of the natural and the synthetic.8For more on the queering of humanness through technology in posthuman fashion, see Georgina Evans, “Posthumanism in Fashion, SHOWstudio, posted June 17, 2018, https://www.showstudio.com/projects/queer/essay_posthumanism_in_fashion.

“We feed and grow on poison.”

To see the subversive potential of these gender-skewing visions, one must understand the social context that gave rise to them—for example, the events leading up the 2021 Tbilisi Pride parade, which were so extreme, they hit the world press. Scheduled to be held on July 5, 2021, the event had to be cancelled due to violent counter-protests in which several civilians were injured in the street rampage of extremist gangs and far-right groups incited and recruited by the Georgian Orthodox church. The homophobic mob attacked people they considered incompatible with the heterosexual male ideal, those wearing earrings or with dyed hair. A television cameraman Lekso Lashkarava lost his life.9While Irakli Garibashvili, prime minister of Georgia, has publicly blamed the Pride organizers for the pogrom that led to the death of Lashkarava, a 2019 National Democratic Institute survey found that only 27 percent of the respondents in Georgia felt that protecting LGBTI rights is important. See “Public Opinion Dynamic Regarding LGBTI Rights—2014–2019,” Women’s Initiatives Supporting Group website, September 18, 2019, https://wisg.org/en/news/detail/254.

In a social reality where being different can be a source of trouble to such a degree, fashion and style—as a form of communication—can have a role in resistance.10See Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London: Routledge, 1979). This explains why Prodiàshvili, Shvelidze, and God Era appear often in the context of contemporary visual and performing arts and as important actors within the city’s queer community.

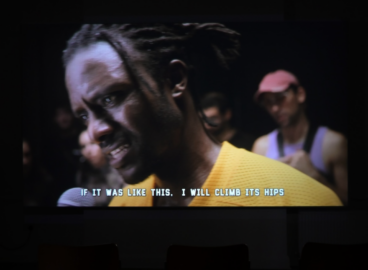

Tbilisi’s queer culture, like a mushroom, feeds and grows “on poison, [on] toxic waste” yet thrives “in damp and dark places,” as the manifesto of Fungus,11Fungus was founded in 2020 by artists David Apakidze (born 1998), Mariko Chanturia (born 1990), K.O.I. (born 1988), Uta Bekaia (born 1974), and Levani (Levan Mindiashvili; born 1979). Since the spring of 2022, their projects have been shown mostly at the Fungus Art Gallery, which is located on the lower level of the House of Reconnextion, a new venue that hosts other queer-feminist organizations (including Creative Collective Spectrum and Horoom Nights). Across the street, an avant-garde bar called Klara recently opened, and there, alongside performances, artist talks, and tarot readings, issues of queer activism are addressed. At present, in collaboration with art historian Nikoloz Nadirashvili, the group is preparing a publication on the history of Georgian queer art. a recently formed interdisciplinary queer art collective, underlines. The amorphous organism composed of emerging and mid-career artists not only embraces the fields of visual arts, fashion, performance, and poetry but also has become interwoven with the city’s vibrant party scene—another important pillar of queer resistance in Georgia. Indeed, the world-renowned Tbilisi nightclub Bassiani and smaller venues12For example, Cafe Gallery, Success, and Drama. play a pivotal role in the life of the community. They are utopian spaces of radical self-expression, creativity, collectiveness, and sexuality, offering a different kind of future than what the conservative establishment has imagined.13During the pandemic, when all of the nightclubs in Tbilisi were closed and people who did not conform to traditional social and/or gender stereotypes had nowhere to congregate, the importance of these clubs became even more tangible. See Jorge Esda, “Tbilisi Pride and the Queer Rights to the City,” Resident Advisor, posted July 15, 2021, https://ra.co/features/3884.

In the Decade of Darkness

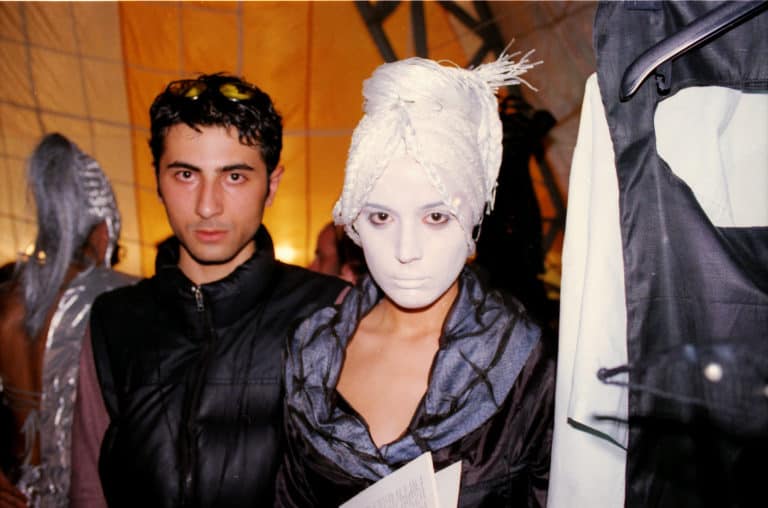

The person who forms the bridge between today’s queer art scene and the avant-garde fashion circles of the 1990s is multimedia artist and costume designer Uta Bekaia (born 1974). In 2017, after spending twenty years in New York, Bekaia returned to Tbilisi, where he became one of the leading figures in the community that founded Fungus. When I spoke to him in 2019, he mentioned Aura, a club that opened in 1996 (before he immigrated to New York), as (one of) the prototype(s) of today’s safe spaces, where party culture meets performance art and fashion.14Uta P. Bekaia, interview by Gyula Muskovics, October 28, 2019. This unofficially queer venue was located on the minus-third floor of the catacombs under Republic Square (today, First Republic Square), and as I discovered during research visits to the Georgian capital, is only vaguely remembered by a few people.

“Everyone was dressed as the opposite sex; girls wore moustaches, boys were in wigs,” recalled LGBT+ activist Paata Sabelashvili (born 1978), who told me that Aura was a safe haven for many musicians, artists and punks, as well as for the gay and lesbian community.15Paata Sabelashvili, interview by Gyula Muskovics, October 4, 2022. Besides the weekly Madonna parties and drag shows, choreographer Ramaz Shamanauri (aka Ramazo Roma or Madlena) held dance performances and Bessarion Razmadze (born 1978) of the brand BEssARION organized fashion shows. The latter was the gayest event of the week, according to Sabelashvili.16Ibid. From time to time, Bekaia—often joined by his friend Zaliko Berger—hit the catwalk of Aura with a glittering collection that was created from found and recycled materials and took inspiration from the 1987 film Wings of Desire by German filmmaker Wim Wenders (born 1945). “It was fascinating to think that just by putting wings on someone, they would turn into a magical, poetic creature,” he explained.17Bekaia, interview by Muskovics. Some of the pieces from this collection appear in a music video by Irakli Charkviani (1961–2006).18Irakli Charkviani was a poet, prose writer, and prominent figure in the alternative rock and electronic music scene in Georgia. The song that features Uta Bekaia, Zaliko Berger, and their works is entitled “Shen afren,” which translates as “You Are crazy.” Yet, the “unbelievably crazy” vibes of Aura, as Bekaia remembered it, were contrasted with the dark atmosphere of the outside reality: “The streets of Tbilisi were scary in the 1990s; there was no taxi or public transport, and so on our way there, we covered our outfits with long coats and hid our makeup with large hoods.”19Bekaia, interview by Muskovics.

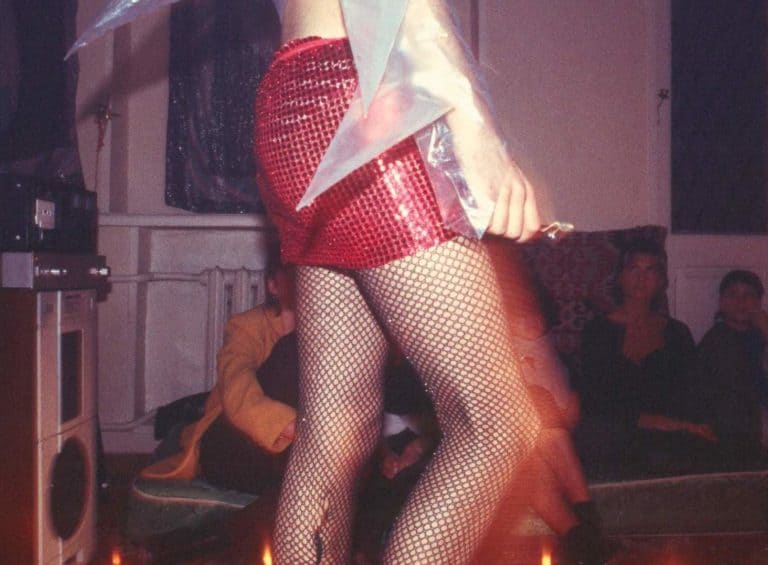

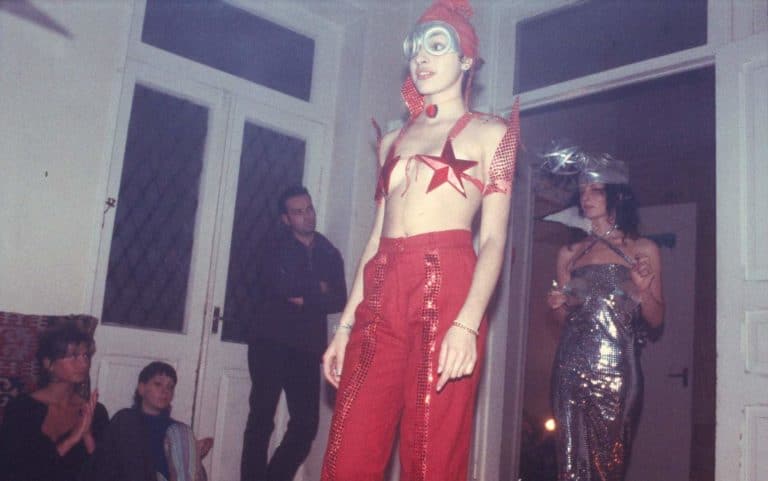

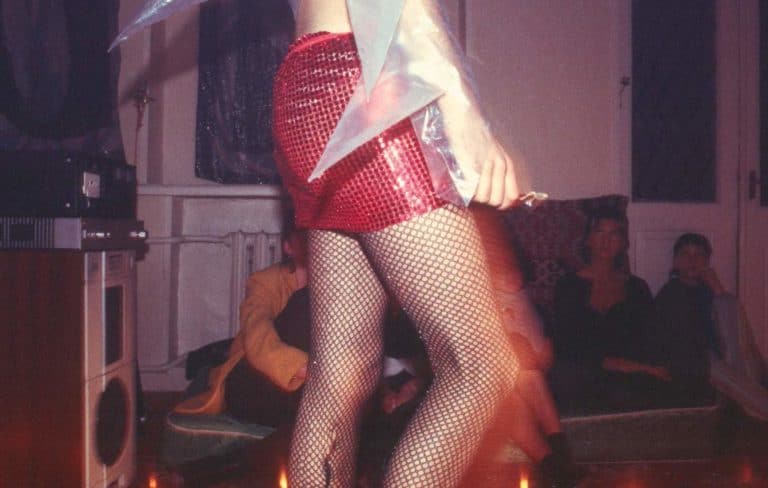

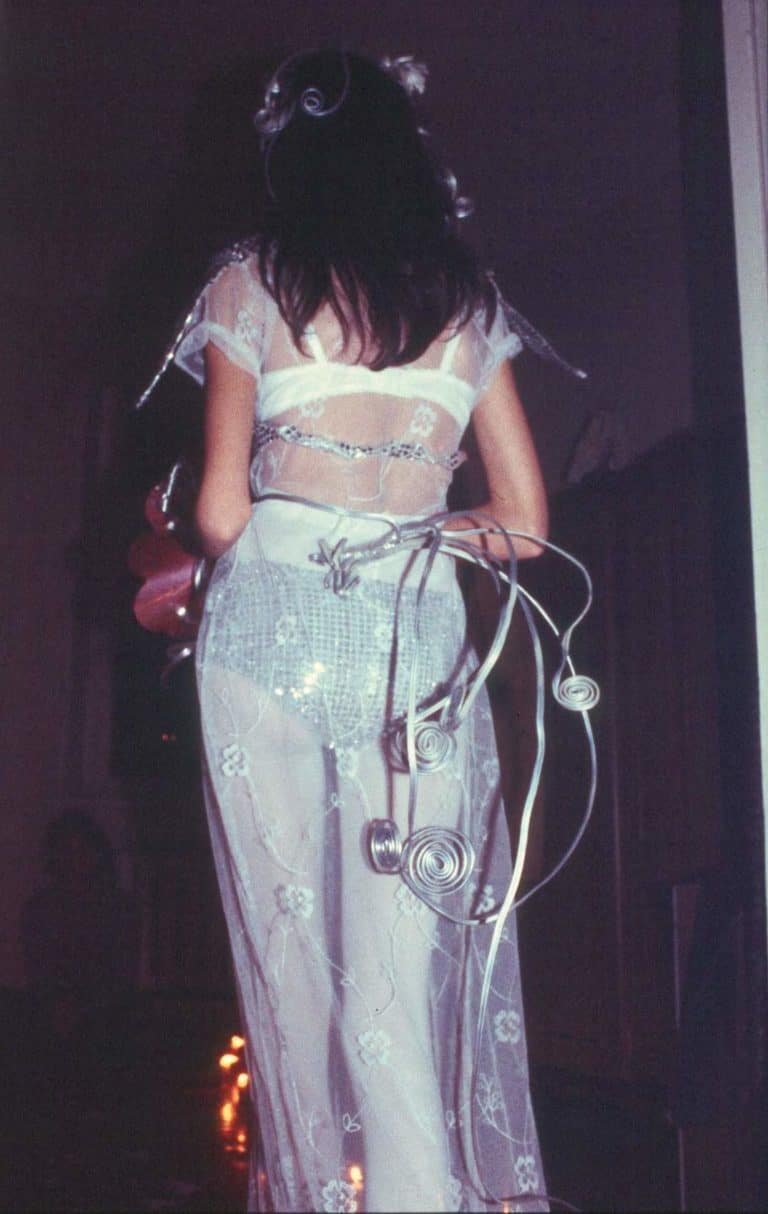

It was the “decade of darkness,” the period after the Georgian civil war,20Ethnic and intranational conflicts in the regions of South Ossetia (1988–92) and Abkhazia (1992–93) as well as the coup against Zviad Gamsakhurdia (1991–92), the first democratically elected president of independent Georgia. which followed the country’s break from the Soviet Union. The mood of the nineties was marked by mourning, fear, drug addiction, and armed criminal gangs. Since on the streets it was not uncommon to encounter people with Kalashnikovs, the avant-garde youth gathered underground and in private apartments. One such place was the home of rock musician Lado Burduli (born 1964), which also served as a venue for gender-bending fashion performances. The “catwalk” through Burduli’s living room was sometimes lit with candles, because back then, the electricity could be out for several days in a row. Besides the unconventional use of shapes and fabrics, the queering of Soviet symbols and the ironic degradation of them into playthings were striking features of the improvised fashion creations that were debuted in Burduli’s apartment. The photographs taken at a show of work by Natia Bakhtadze in 1995 by Guram Tsibakhashvili (born 1960)—who documented Tbilisi’s underground art circles in the 1990s—clearly demonstrate this. Bakhtadze presented five pieces, including two otherworldly, glittery silver evening dresses, a red dress worn by a little girl, and two androgynous outfits covering the model’s upper bodies with transparent plastic foil and communist red stars.21Designer Besarion Razmadze (born 1978) presented his collection at Burduli’s apartment on this same evening.

In certain parts of the Eastern bloc, such irony in art was already common by perestroika (1985–91), the period leading to the collapse of the Soviet Union.22See Gyula Muskovics, “Eastern-European Avant-Garde Fashion. Tamás Király and His Soviet contemporaries,” East Art Mags, posted February 1, 2020, https://artportal.hu/magazin/eastern-european-avant-garde-fashion-tamas-kiraly-and-his-soviet-contemporaries/. In Georgia, however, the weakening of the regime, which left little room for alternative culture, brought about the rise of nationalism.23Gia Khaudri, “Mental Transformation in Post-Soviet Tbilisi,” in Tbilisi: Archive of Transition, ed. Klaus Neuburg et al. (Salenstein: Niggli, 2018), 149. The imprisonment of world-famous filmmaker Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990) in the 1970s and then again in 1982 on account of homosexuality and for his poetic films subverting Soviet Realism illustrates the regime’s rigidity during this time.24Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990) was a Georgian film director of Armenian origin, a screenwriter, and an artist regarded as one of the most influential filmmakers in cinema history. The outlandish costumes and magical makeup featured in his films make him relevant in the context of this article. Furthermore, in his 1969 classic The Color of Pomegranates, the protagonist, played by actress Sofiko Chiaureli, appears in six different roles, both male and female. At the end of the 1980s, the artists of the Marjanishvili Theatre collective, such as Oleg Timchenko (born 1957), Niko Tsetskhladze (born 1959), and Mamuka Japaridze (born 1962), were among the first to experiment with the role of costumes in performance art.25Skangale, “An Underground Bridge to Georgian Collectiveness.” Part of the reason for this was that they had plenty of material available in the theater where their studio was located. For example, the costumes in Stand Against, a public performance in 1991 by Timchenko and Tsetskhladze, were important elements of the composition. In this work, like two mafiosi or questionable politicians of the time, the artists were dressed in suits and sunglasses as they stood motionless in an empty shop window in the underpass at Kolkhoz Square (today, Orbeliani Square). Their faces painted gold, they silently watched the passersby like mannequins, before suddenly breaking the glass and stepping out of the window onto the street. This action was not a fashion experiment but rather a way of drawing attention to the urgent need to resist what had become an increasingly stagnant and repressive society.

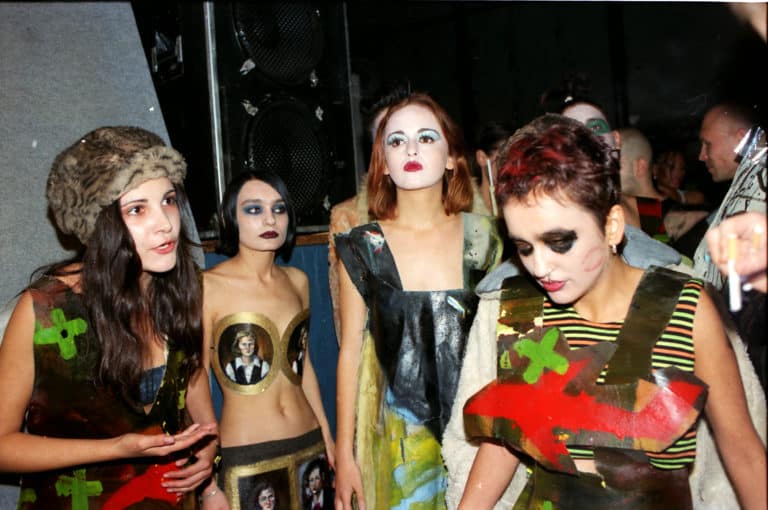

By the mid-1990s, fashion designers were also beginning to respond to the mood of Georgian society in different ways—some with more irony than others. An example of an artist who pursued the latter tack is Nino Chubinishvili (aka Chubika; born 1969), whose 1996 Dead Army collection of approximately thirty pieces was inspired by the omnipresent chaos. The dresses, which evoke the Chinese Terracotta Army in color and style, were made of bluish-gray impregnated canvas, which also recalls the texture of the water-repellent tablecloths ubiquitous in Soviet households, and they covered the whole body, including the head. Each model had a black-and-white photograph depicting an everyday scene attached to their chest. These images of sweet yet painful scenes of life amid devastation26Nino Chubinishvili, interview by Gyula Muskovics, November 6, 2019. were taken by Giorgi Sumbadze (born 1976) as part of a photo series depicting blind and androgynous models walking among abandoned tanks and landmines in the Gareji desert near the border of Azerbaijan. As the artist commented retrospectively in a conversation about her intuitive and inventive process, “Georgians have a fixation on death.”27Ibid. At the beginning of her career, due to her limited knowledge of the unconventional materials that would later become central to her practice at the intersection of sculpting and fashion, this approach was essential. Dead Army was the first collection Chubika presented at the Avant-Garde Fashion Assembly.

“The only bright spot:” The Avant-Garde Fashion Assembly

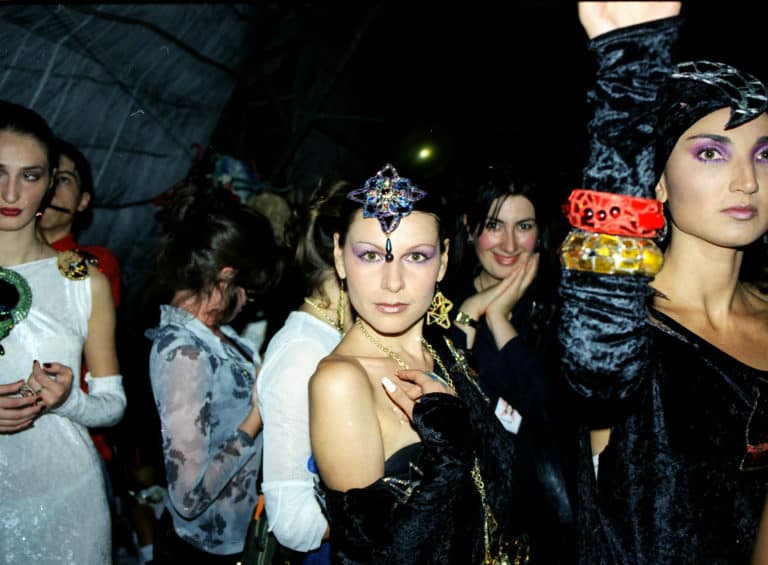

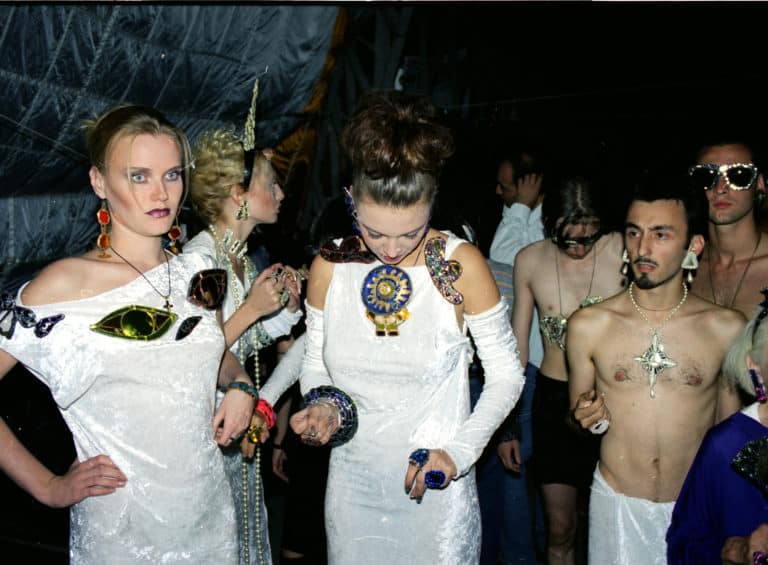

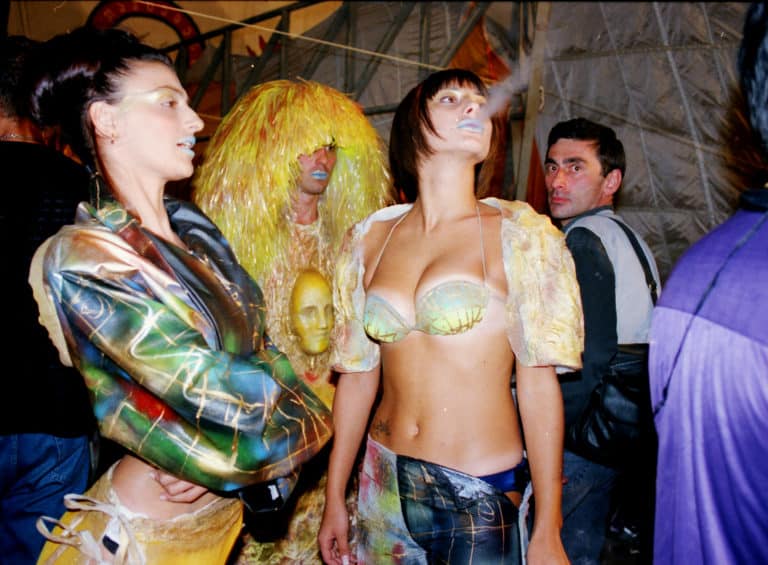

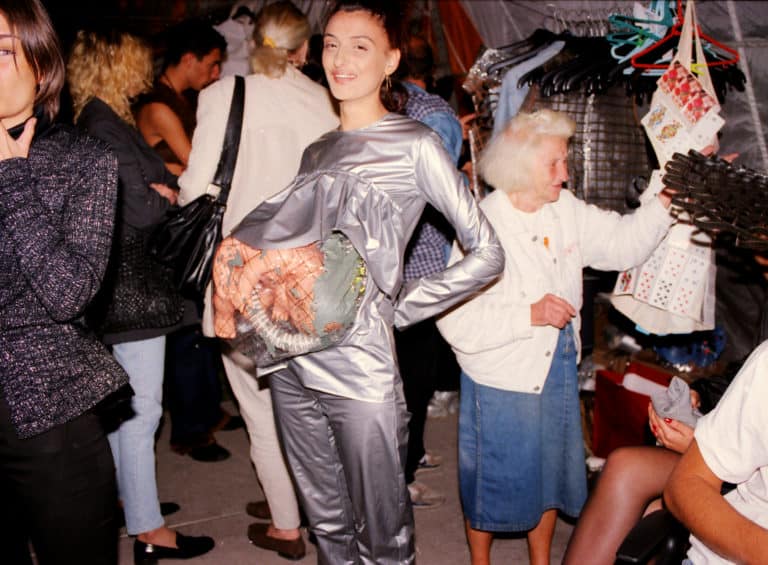

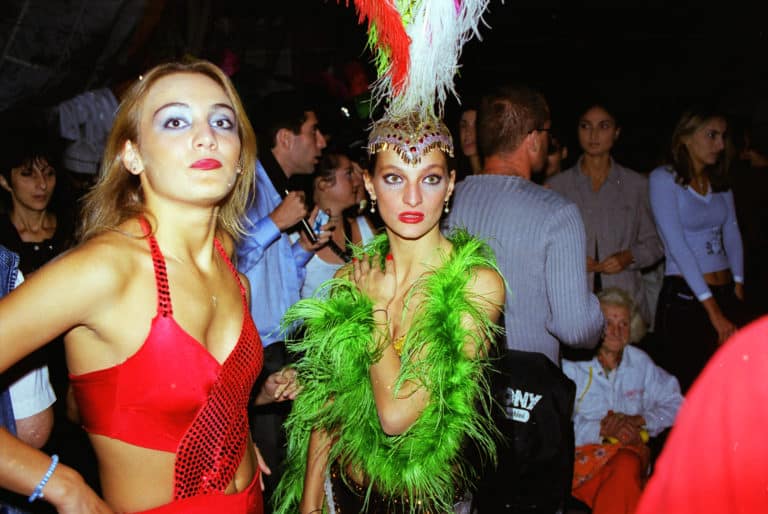

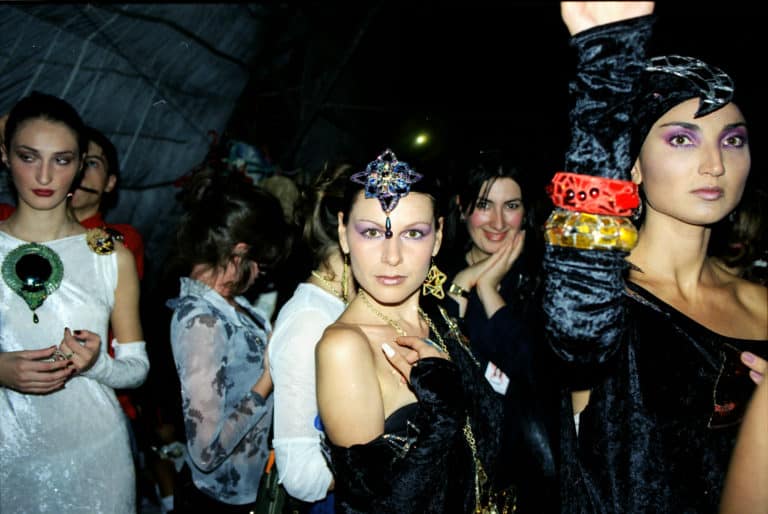

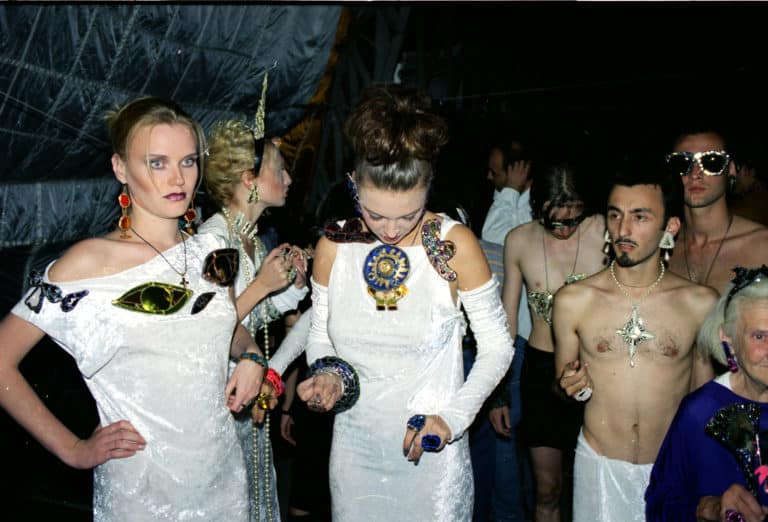

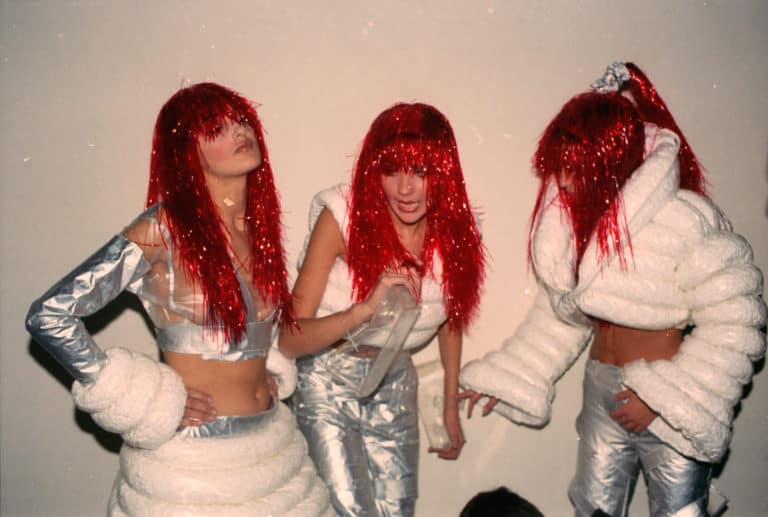

The Avant-Garde Fashion Assembly (AMA) was a grandiose multidisciplinary event dedicated to electronic music, art, and fashion, in which not only bodies but also artistic genres were queered to illuminate the city anew, amid the postwar chaos that defined Georgia throughout the 1990s. According to many, it was a light in the darkness. “This one-week celebration, a mix of the Carnival of Brazil and an artistic hangout, was the only bright spot in the otherwise gray environment,” is how Tsibakhashvili, whose photo archive served as the visual foundation for this article, recalls it.28Guram Tsibakhashvili, Winter Is Over (Tbilisi: Indigo Publishing, 2019), 186. The assembly, which brought together Georgian and international fashion designers and artists, mostly (but not only) from the post-Soviet countries, was held only three times—in 1995, 1996, and 1999. The venue was the Georgian Expo (VDNKh). The catwalk, which was suspended as a bridge above the lake in front of the main building, is still there today. In a way, this can also be seen as a queer gesture: Where else would the parade of the young generation exploring possibilities of self-expression after the social and economic collapse have taken place if not in an exhibition complex dedicated to the achievements of the Soviet Union?

In 1995, the jury included Christophe Girard (born 1956), executive vice president of Yves Saint Laurent; Lithuanian designer Sandra Straukaite (born 1970); and Japanese artist Shozo Shimamoto (1928–2013), among others. The event was supported by George Soros’s Open Society Foundations, as I learned in an interview with poet and performance artist David Chikhladze (born 1962), who developed the theoretical concept of the first AMA under the title “Land of Venus.”29David Chikhladze, interview by Gyula Muskovics, September 24, 2021. The idea was to demystify fashion, a theoretical concept that, according to Chikhladze, could not be fully translated into practice. However, it was clear that the real goal was not to counter high fashion, which did not exist in Tbilisi at the time, but rather to be “the embryo of an independent sociocultural performance.”30Ibid.

The five-day event, held in eleven pavilions, gave hope to both the public and participants that everything would soon be back in place. As nothing like this was happening in Tbilisi at the time, at least on this scale, people were craving culture, and the AMA encouraged them to step out of the “survival mode” of their daily lives and start dreaming, celebrating, and organizing themselves. Avant-garde fashion emphasized the power of togetherness and the need to speak out, to make a statement, as opposed to revolving around conceptual and theoretical questions in art. The artists—who by now were familiar with glamorous video clips from the West—were promoting the idea of having fun while laying the foundation for a cross-disciplinary platform based on collaboration.

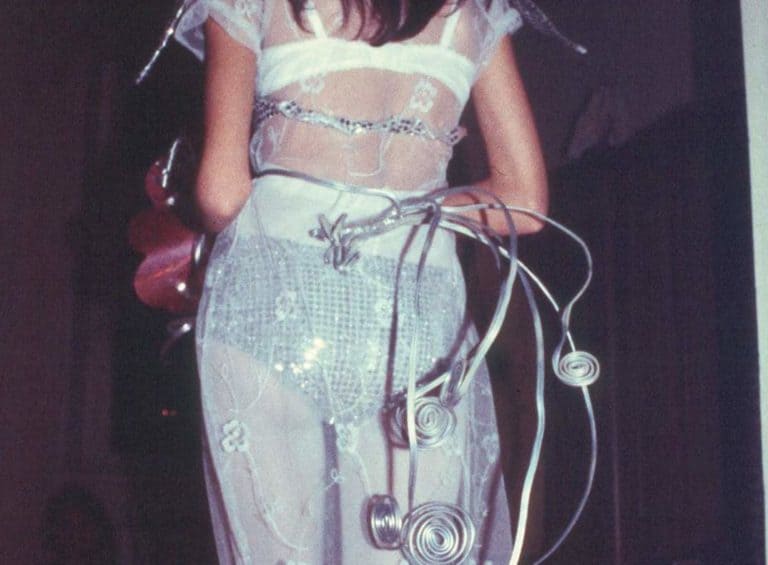

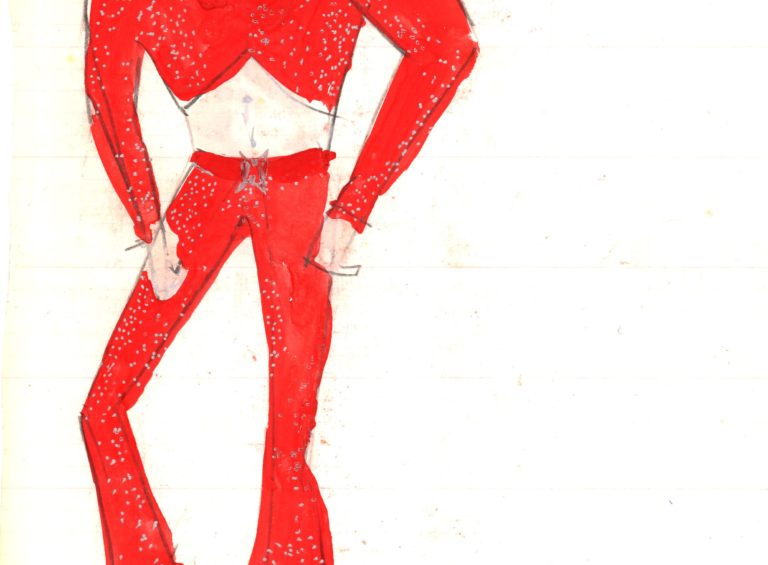

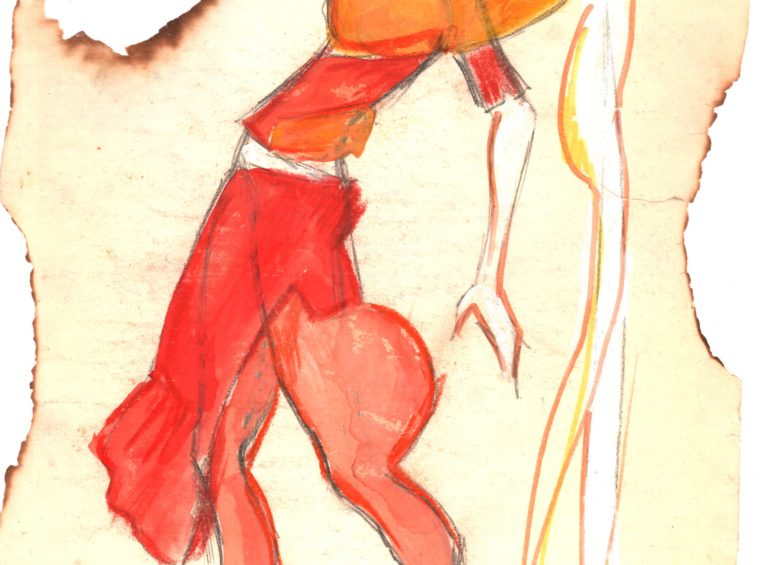

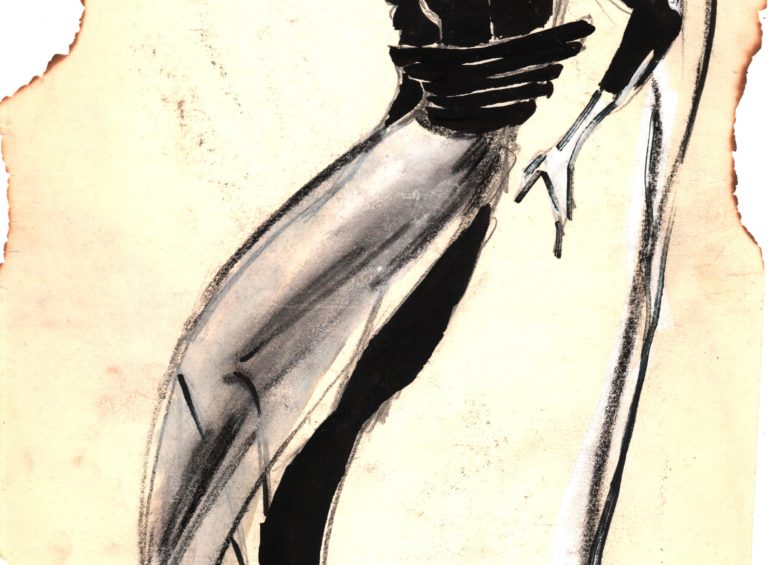

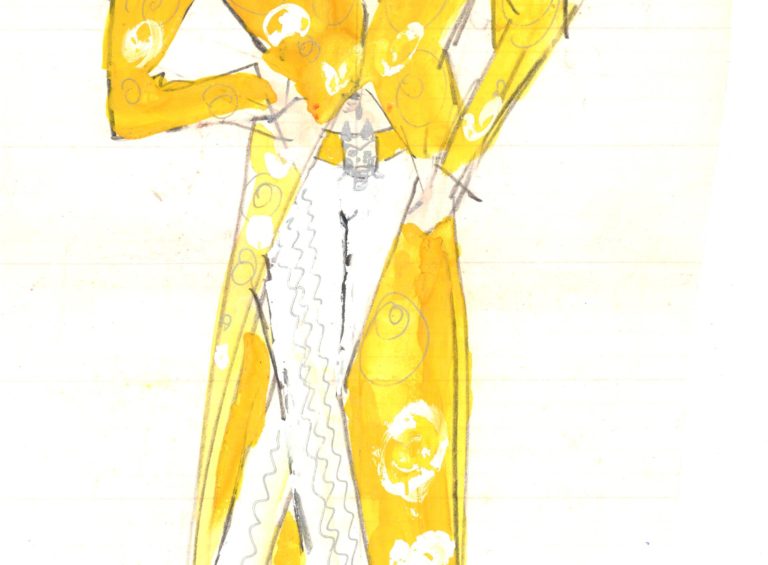

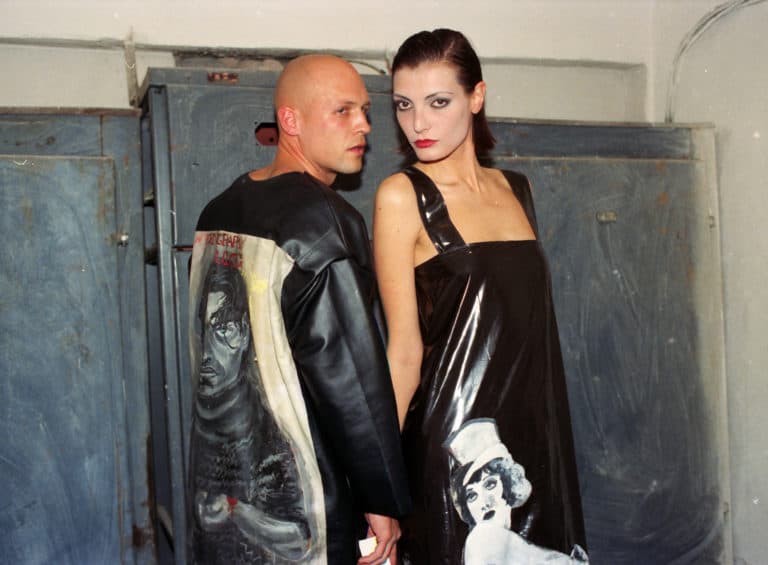

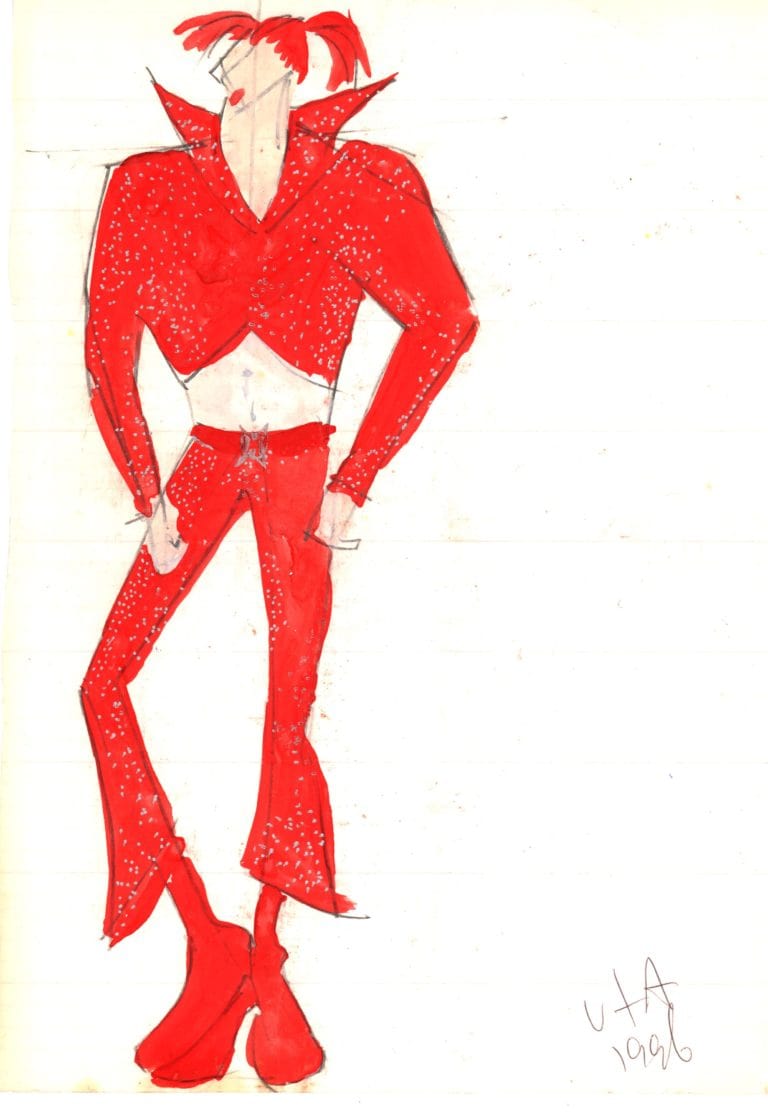

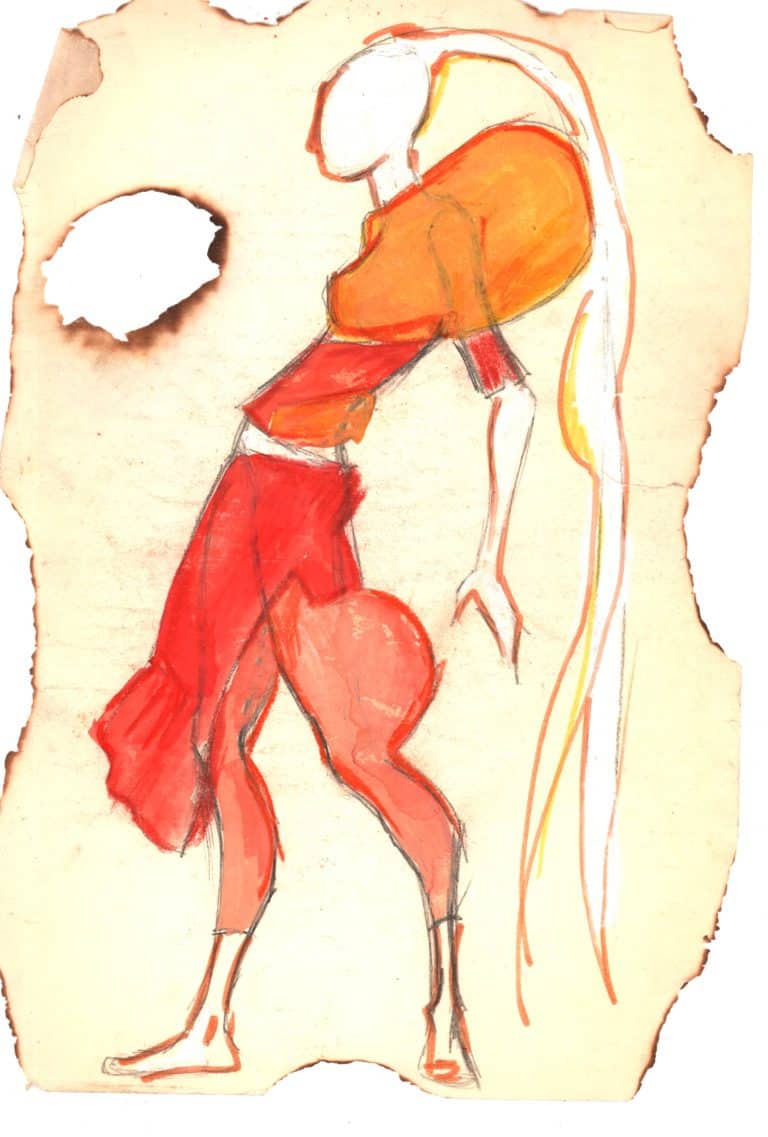

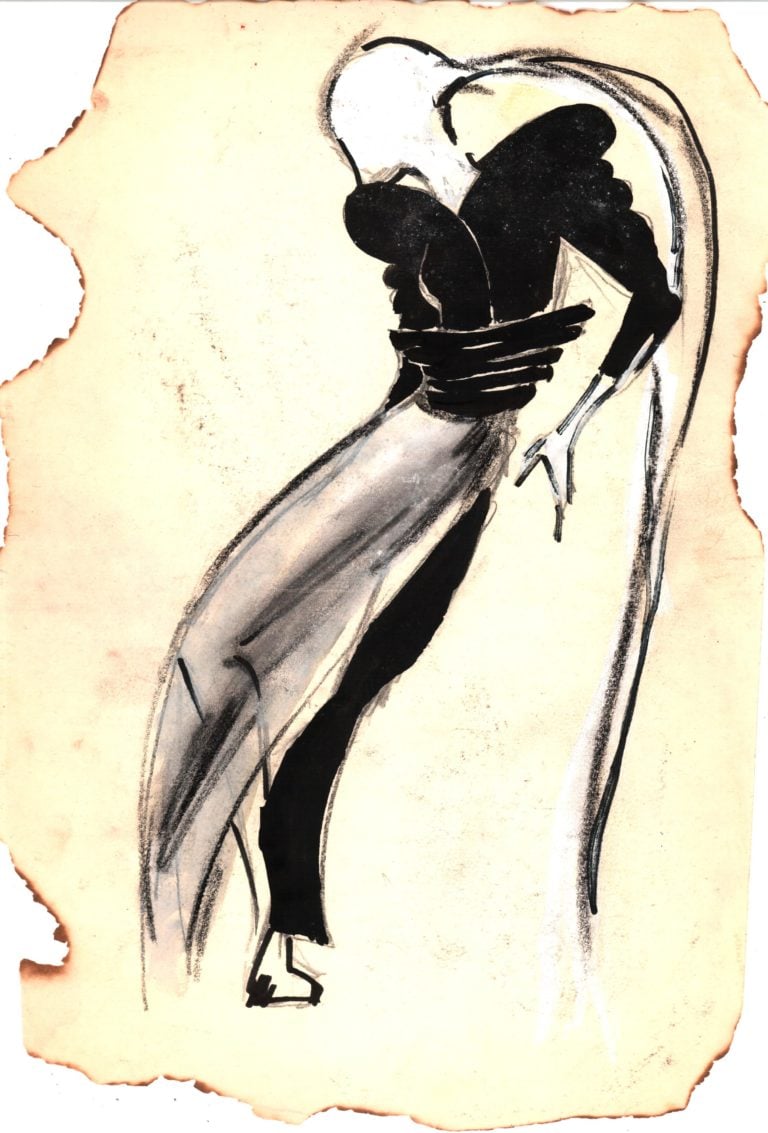

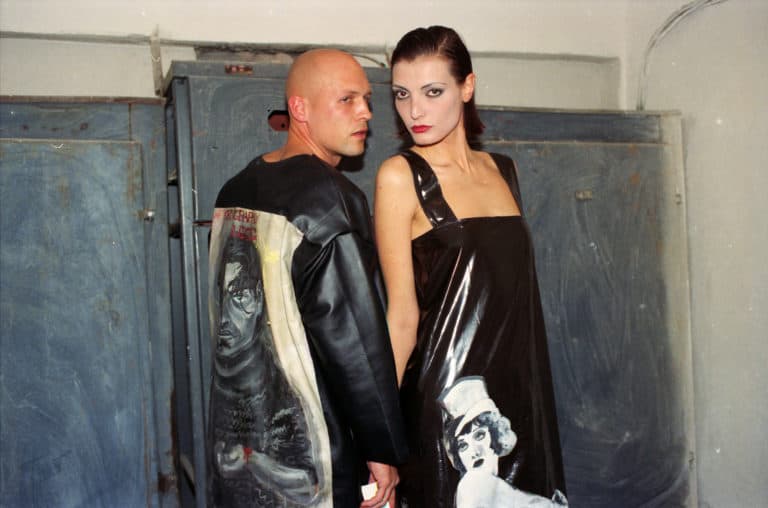

It was all about experimentation and creativity, and the participants, alongside fashion designers, included architects as well as visual artists. Zaliko Berger, for example, took the play with genres so seriously that he cut the dresses he showed at the 1996 assembly from paintings in his collection. For Bekaia, who studied industrial design (as had Berger and many other artists not originally trained as fashion designers), the 1996 AMA provided the opportunity to create what would be his first fashion collection. It was inspired by nineties techno, which accompanied the show; as the dance music played, models in brightly colored monochrome outfits, their hair painted to match, walked down the runway in platform shoes with wooden soles.31Bekaia, interview by Muskovics. The main prize in 1996 went to visual artist Maya Sumbadze (born 1972), who designed six dresses made of transparent plastic lined with hay and wildflowers from Dusheti, where she is from.32When I met Maya Sumbadze on September 15, 2021, in Tbilisi, she was unsure whether the collection consisted of six or seven pieces. The short show was set to music by Nika Machaidze (born 1972) and Gogi Dzodzuashvili (born 1971), with whom Sumbadze, alongside Chubika and others, would later form the multimedia artist group Goslab.33Goslab was formed in 1999, but its members had worked together unofficially since the beginning of the 1990s. Group members were Nino Chubinashvili, Thea Djordjadze (born 1971), Maya Sumbadze, Salome Machaidze (born 1973), Natalie TBA Beridze (born 1979), Gogi Dzodzuashvili (born 1971), Zaza Rusadze (born 1977), Tamuna Karumidze (born 1975), Levan Nutsubidze, and Giorgi Sumbadze (born 1976).

The popularity of this form of expression among visual artists was partly due to the fact that though wearable fashion requires a certain level of expertise, the AMA did not have such expectations of its participants. In fact, the event seems to prove that the less skilled you were, the crazier the creations you put together. Furthermore, as shown above, it did not require any particular material resources. Despite the difficult conditions, these fashion shows, in highlighting the transformation and abstraction of the human body, and demonstrating the subject in the process of becoming, can be interpreted through the lens of feminist and queer discourses of the 1990s.

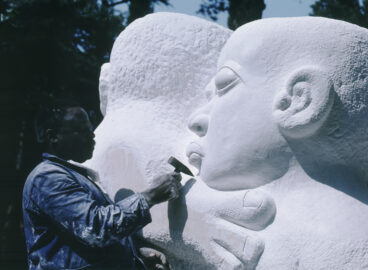

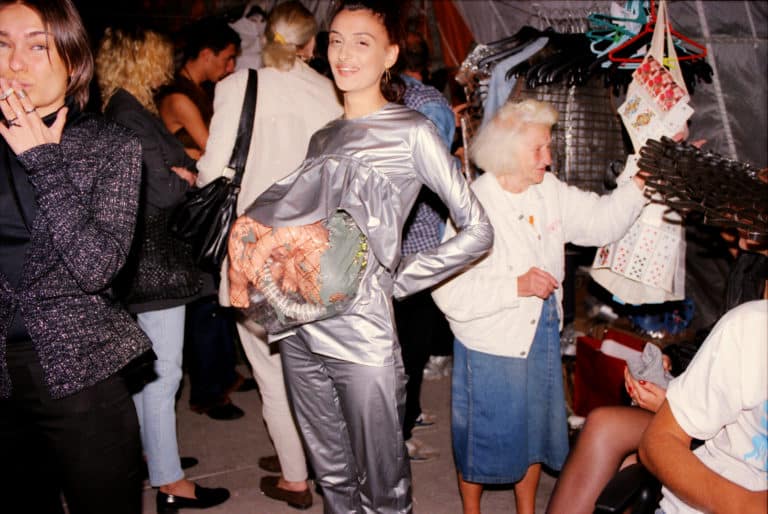

The AMA, through its international roster of guests, has only further encouraged such cross-pollination, cultural exchange, and the clash of perspectives and contexts. Artist and avant-garde fashion creator Alexander Petlura (born 1955), already well-known in Moscow’s alternative fashion circles as a collector of trash, attended the event twice.34Secondhand clothes, accessories, and rare objects that serve as the basis for his fashion creations. As photographs of the event show, in 1999, he was accompanied by his muse, seventy-five-year-old Pani Bronya (1924–2004), who had won the Alternative Miss World award in London the previous year. This “beauty” contest, which is held every four to five years, was founded by British sculptor and performance artist Andrew Logan (born 1945) in the 1970s and has celebrated such queer icons as Derek Jarman (1942–1994), Leigh Bowery (1961–1994), and Divine (1945–1988).35The Alternative Miss World celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in October 2022. Logan was closely involved with the avant-garde fashion community in the Eastern bloc, and so it is no surprise that he also participated in the last edition of the AMA, injecting a booster shot of camp sensibility into the 1990s Georgian art scene.

The AMA was the brainchild of young designer Gela Kuprashvili (born 1972), who modeled it on the Untamed Fashion Assembly (UFA), a similar event that took place in Riga almost every year between 1990 and 1999.36Gela Kuprashvili, interview by Gyula Muskovics, October 22, 2019. The UFA was the region’s first large-scale fashion show in which Eastern and Western designers and artists joined forces in confronting the mainstream with unconventional sculptural creations. In 1994, Paco Rabanne (born 1934) also participated. Andrey Bartenev (born 1965) who, along with Katya Filippova (born 1958), is perhaps the best-known figure in Moscow’s alternative fashion scene, debuted in 1992 with the Botanical Ballet —a giant papier-mâché costume collection. To a lesser extent, but a few years earlier, similar efforts had been made in the Soviet satellites. Ceremoniously preparing for the inescapable fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Hungarian fashion designer Tamás Király (1952-2013) staged his avant-garde fashion shows at the Petőfi Music Hall in Budapest.37For more on Tamás Király’s fashion shows in the period between the opening of the Petőfi Music Hall in 1985 and 1989, see Gyula Muskovics, “The Dreamworld of Tamás Király,” in Tamás Király ’80s, ed. Gyula Muskovics and Andrea Soós (Budapest: Tranzit.hu, Budapest, 2017), 28–37, https://gyulamuskovics.com/files/dreamworld%20of%20tama%CC%81s%20kira%CC%81ly_v2.pdf. Király was one of the few avant-garde designers in Central and Eastern Europe, and the only one in Hungary, but he compensated for this with the size of his events. He brought his visions to life, if necessary, through more than a hundred garments, with contributions by alternative music bands, as well as the onstage presence of child models, bodybuilders, and animals.

Builders of Utopia

The AMA and similar events are enlightening in two ways: On the one hand, they show that despite the assumptions of the dominant art historical narrative, which superficially compares the “belated” East with the “progressive” West, postmodern and queer ideas about body and identity were not absent in the former Eastern bloc.38For more on this, see Gyula Muskovics, “Against Interpretation. On the Performance Art of El Kazovsky and Tamás Király,” East Art Mags, March 27, 2018, https://artportal.hu/magazin/against-interpretation-on-the-performance-art-of-el-kazovsky-and-tamas-kiraly/. Yet, a closer look at the socioeconomic context in which these avant-garde visions took form reveals an important difference: In the West, DIY, bricolage, and inventiveness in fashion stood in opposition to consumer capitalism and mass production. In the East, however, in the vacuum that preceded and followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the main source of artistic imagination was scarcity—that is, the absence of a stable economy with a functioning industry and material resources—which fostered a certain freedom in terms of creativity.39For a more in-depth analysis of this, see Muskovics, “Eastern-European Avant-garde Fashion.” Nevertheless, avant-garde fashion in Eastern Europe in the 1980s and the 1990s offered delicate and fresh takes on gender, fashion, and the values that have come to define beauty.

As the UFA’s main organizer Bruno Birmanis has noted, “The nineties is the period that everyone remembers, but that nobody has precise memories of,”40“Untamed Fashion of the Eastern Bloc: Cult fashion Designer Bruno Birmanis Interviewed by Gyula Muskovics,” East East, posted January 25, 2021, https://easteast.world/en/posts/209. which my own research confirms. In this text, I weave local fashion phenomena in Tbilisi with the larger network of similar events in the former Eastern bloc as well as with global trends to show that the line separating East and West is not as clear as mainstream art history implies. Furthermore, in response to the post-Soviet fashion trend, I would like to suggest that the artists of the 1990s have already exhausted the notion of post-Soviet, in the sense that they responded in various ways to the fall of Soviet ideology and the turmoil that followed it.41See Kirill Kobrin, “Welcome to the Post-Post-Soviet Era,” Open Democracy, posted October 26, 2016, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/welcome-to-post-post-soviet-era/. As schizo-analysts of rootless societies in a turbulent decade, they opened windows onto realities that existed merely at the level of dreams and fantasies. They also laid a foundation for the new generation, which has an equally important role to play, especially in the highly charged sociopolitical environment of Tbilisi: They are the builders of a utopia that allows us to imagine that something beyond what we accept as reality is possible. And this is essential to bringing about change in society. Although, there will always be new challenges, the work should never start from the beginning. The experiences of our ancestors are fundamental to such world-building projects.

The contributor would like to thank David Apakidze and Nikoloz Nadirashvili for their extensive help in navigating Tbilisi’s contemporary art and fashion circles during his research visits and beyond.

Exhaustive efforts have been made to confirm the accuracy of the information provided in the article; omissions brought to our attention will be corrected accordingly.

- 1For a summary see, Gyula Muskovics, “What Is Not New in the ‘New East’?—Post-Soviet Fashion and the 1980s,” East Art Mags, posted October 13, 2019, https://artportal.hu/magazin/what-is-not-new-in-the-new-east-post-soviet-fashion-and-the-1980s/.

- 2See, for example, Anastasiia Fedorova, “Post-Soviet Fashion: Identity, History and the Trend that Changed the Industry,” Calvert Journal, posted February 23, 2018, https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/9685/post-soviet-visions-fashion-aesthetics-gosha-demna-lotta-vetements.

- 3See Vija Skangale, “An Underground Bridge to Georgian Collectiveness: Finding a Tribe through Collective Trauma,” post: notes on art in a global context, posted July 15, 2022, https://post.moma.org/an-underground-bridge-to-georgian-collectiveness-finding-a-tribe-through-collective-trauma/.

- 4The Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week Tbilisi was founded in 2015 by Sofia Tchkonia. The fact that Demna [Gvasalia] (born 1981), who is now creative director of Balenciaga, and other designers such as George Keburia (born 1990) or Irakli Rusadze (born 1991) of Situationist, have also made their way to the epicenter of the fashion world has a lot to do with Tchkonia’s work.

- 5See Liana Satenstein, “In Georgia, One Young Designer Is Bringing Drag to the Runway,” Vogue, posted November 12, 2018, https://www.vogue.com/article/aka-prodiashvili-tbilisi-fashion-week-drag-rupauls-drag-race.

- 6Nino Sichinava, “Meet Levau Shvelidze the Eccentric and Self-Declaring Designer You Should Know,” Fucking Young, posted April 21, 2022, https://fuckingyoung.es/meet-levau-shvelidze-the-eccentric-and-self-declaring-designer-you-should-know/.

- 7Liana Satenstein, “Tbilisi’s Most Photographed Street Style Star Accessorizes with Plastic Dolls,” Vogue, posted November 9, 2018, https://www.vogue.com/article/nini-goderigidze-tbilisi-street-style-star.

- 8For more on the queering of humanness through technology in posthuman fashion, see Georgina Evans, “Posthumanism in Fashion, SHOWstudio, posted June 17, 2018, https://www.showstudio.com/projects/queer/essay_posthumanism_in_fashion.

- 9While Irakli Garibashvili, prime minister of Georgia, has publicly blamed the Pride organizers for the pogrom that led to the death of Lashkarava, a 2019 National Democratic Institute survey found that only 27 percent of the respondents in Georgia felt that protecting LGBTI rights is important. See “Public Opinion Dynamic Regarding LGBTI Rights—2014–2019,” Women’s Initiatives Supporting Group website, September 18, 2019, https://wisg.org/en/news/detail/254.

- 10See Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London: Routledge, 1979).

- 11Fungus was founded in 2020 by artists David Apakidze (born 1998), Mariko Chanturia (born 1990), K.O.I. (born 1988), Uta Bekaia (born 1974), and Levani (Levan Mindiashvili; born 1979). Since the spring of 2022, their projects have been shown mostly at the Fungus Art Gallery, which is located on the lower level of the House of Reconnextion, a new venue that hosts other queer-feminist organizations (including Creative Collective Spectrum and Horoom Nights). Across the street, an avant-garde bar called Klara recently opened, and there, alongside performances, artist talks, and tarot readings, issues of queer activism are addressed. At present, in collaboration with art historian Nikoloz Nadirashvili, the group is preparing a publication on the history of Georgian queer art.

- 12For example, Cafe Gallery, Success, and Drama.

- 13During the pandemic, when all of the nightclubs in Tbilisi were closed and people who did not conform to traditional social and/or gender stereotypes had nowhere to congregate, the importance of these clubs became even more tangible. See Jorge Esda, “Tbilisi Pride and the Queer Rights to the City,” Resident Advisor, posted July 15, 2021, https://ra.co/features/3884.

- 14Uta P. Bekaia, interview by Gyula Muskovics, October 28, 2019.

- 15Paata Sabelashvili, interview by Gyula Muskovics, October 4, 2022.

- 16Ibid.

- 17Bekaia, interview by Muskovics.

- 18Irakli Charkviani was a poet, prose writer, and prominent figure in the alternative rock and electronic music scene in Georgia. The song that features Uta Bekaia, Zaliko Berger, and their works is entitled “Shen afren,” which translates as “You Are crazy.”

- 19Bekaia, interview by Muskovics.

- 20Ethnic and intranational conflicts in the regions of South Ossetia (1988–92) and Abkhazia (1992–93) as well as the coup against Zviad Gamsakhurdia (1991–92), the first democratically elected president of independent Georgia.

- 21Designer Besarion Razmadze (born 1978) presented his collection at Burduli’s apartment on this same evening.

- 22See Gyula Muskovics, “Eastern-European Avant-Garde Fashion. Tamás Király and His Soviet contemporaries,” East Art Mags, posted February 1, 2020, https://artportal.hu/magazin/eastern-european-avant-garde-fashion-tamas-kiraly-and-his-soviet-contemporaries/.

- 23Gia Khaudri, “Mental Transformation in Post-Soviet Tbilisi,” in Tbilisi: Archive of Transition, ed. Klaus Neuburg et al. (Salenstein: Niggli, 2018), 149.

- 24Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990) was a Georgian film director of Armenian origin, a screenwriter, and an artist regarded as one of the most influential filmmakers in cinema history. The outlandish costumes and magical makeup featured in his films make him relevant in the context of this article. Furthermore, in his 1969 classic The Color of Pomegranates, the protagonist, played by actress Sofiko Chiaureli, appears in six different roles, both male and female.

- 25Skangale, “An Underground Bridge to Georgian Collectiveness.”

- 26Nino Chubinishvili, interview by Gyula Muskovics, November 6, 2019.

- 27Ibid.

- 28Guram Tsibakhashvili, Winter Is Over (Tbilisi: Indigo Publishing, 2019), 186.

- 29David Chikhladze, interview by Gyula Muskovics, September 24, 2021.

- 30Ibid.

- 31Bekaia, interview by Muskovics.

- 32When I met Maya Sumbadze on September 15, 2021, in Tbilisi, she was unsure whether the collection consisted of six or seven pieces.

- 33Goslab was formed in 1999, but its members had worked together unofficially since the beginning of the 1990s. Group members were Nino Chubinashvili, Thea Djordjadze (born 1971), Maya Sumbadze, Salome Machaidze (born 1973), Natalie TBA Beridze (born 1979), Gogi Dzodzuashvili (born 1971), Zaza Rusadze (born 1977), Tamuna Karumidze (born 1975), Levan Nutsubidze, and Giorgi Sumbadze (born 1976).

- 34Secondhand clothes, accessories, and rare objects that serve as the basis for his fashion creations.

- 35The Alternative Miss World celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in October 2022.

- 36Gela Kuprashvili, interview by Gyula Muskovics, October 22, 2019.

- 37For more on Tamás Király’s fashion shows in the period between the opening of the Petőfi Music Hall in 1985 and 1989, see Gyula Muskovics, “The Dreamworld of Tamás Király,” in Tamás Király ’80s, ed. Gyula Muskovics and Andrea Soós (Budapest: Tranzit.hu, Budapest, 2017), 28–37, https://gyulamuskovics.com/files/dreamworld%20of%20tama%CC%81s%20kira%CC%81ly_v2.pdf.

- 38For more on this, see Gyula Muskovics, “Against Interpretation. On the Performance Art of El Kazovsky and Tamás Király,” East Art Mags, March 27, 2018, https://artportal.hu/magazin/against-interpretation-on-the-performance-art-of-el-kazovsky-and-tamas-kiraly/.

- 39For a more in-depth analysis of this, see Muskovics, “Eastern-European Avant-garde Fashion.”

- 40“Untamed Fashion of the Eastern Bloc: Cult fashion Designer Bruno Birmanis Interviewed by Gyula Muskovics,” East East, posted January 25, 2021, https://easteast.world/en/posts/209.

- 41See Kirill Kobrin, “Welcome to the Post-Post-Soviet Era,” Open Democracy, posted October 26, 2016, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/welcome-to-post-post-soviet-era/.