The prefix “para-” stages an ancillary relation: near, beside, beyond, off, away. Across the series of essays that comprise Paracuratorial Southeast Asia, we look at the “paracuratorial”: methods, sensibilities, frameworks, and practices that work within, alongside, or as supplement to exemplary curatorial frameworks such as the exhibition or the collection. The series of essays focuses on how the paracuratorial plays out as a way to annotate, mediate, or even unsettle the forms and kinds of knowledges that become hegemonic within these curatorial frameworks, from discourses of the regional or the national to questions of the art historical.

The somewhat offhand archive called Track Changes nests in the permanent, and therefore more premeditated, display of the art collection of the Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Filipiniana Research Center at the University of the Philippines in Manila. The items in this collection are organized according to a loose art-historical diachrony and within broadly conceived tropes of light, province, unease, and passage. Layered around this nucleus of privileged objects are select contemporary artworks and archival materials. The latter comprise Track Changes, which aims to introduce the public to the archives of the Vargas Museum and the University of the Philippines. The clusters of things are rendered equivalent to and contemporaneous with the encounter of the art through a paracuratorial supplement that exists adjacently to the collection; this arrangement enhances a porous scenography that pursues the interdisciplinarity research inscribed in the word “Filipiniana,” which may mean anything, and so everything, or at the very least, something Philippine. And because Track Changes reminds the public that the museum is the custodian of more than just art as validated by an elite and an expert class, it alerts them to the redistribution of the values of the motley “stuff” of which the museum is steward.

In certain ways, the initiation is an insertion into the stable canon of the collection, thus alluding to a “distraction,” to drag or to pull in different directions in Latin and late Middle English, but not altogether a disruption. It is a practical diversion, so to speak, a delay of expectation consisting of vitrines resting on the spindly legs of wooden tables that may easily be moved or stored. The room housing the collection is surrounded by glass, the panes of which are framed by aluminum, and dappled by various illuminations at different times of the day from the outside. Not a typical white cube, it situates the viewer amid art and nature in a kind of wraparound transparency that instills the feeling of being in a museum and, at the same time, experiencing a kind of continuum with external happenstance, be it rain or a riot. Track Changes is both implicit and complicit, receding and advancing within the institution but not seeking a center; in fact, it is at the sides, flush to the glass wall and so invites oblique reading in the way of an annotation or an aside. While sufficiently present, it is neither ubiquitous nor conspicuous: rather, it is intermingled and intermittent though delicately indented.

The initiation into this endeavor is titled The Native Strain: Guillermo Tolentino and Aurelio Alvero. It focuses on the relationship between Jorge B. Vargas (1890–1980), collector and donor of the collection; artist-professor Guillermo Tolentino (1890–1976); and curator-critic Aurelio Alvero (1913–1958). These three figures are related at certain nodes. Vargas collected the stalwart academic sculptor Tolentino, and Alvero helped Vargas set up his collection. Furthermore, the archives of Tolentino are in the University of the Philippines, which administers the Vargas collection and where Vargas was a student in its first law class and later a regent. Relating Tolentino and Alvero to Vargas is particularly intriguing as it gives us a glimpse into the aesthetic and political implications of making art, making nationalisms, and making museums in the interwar, war, and postwar years in the Philippines.

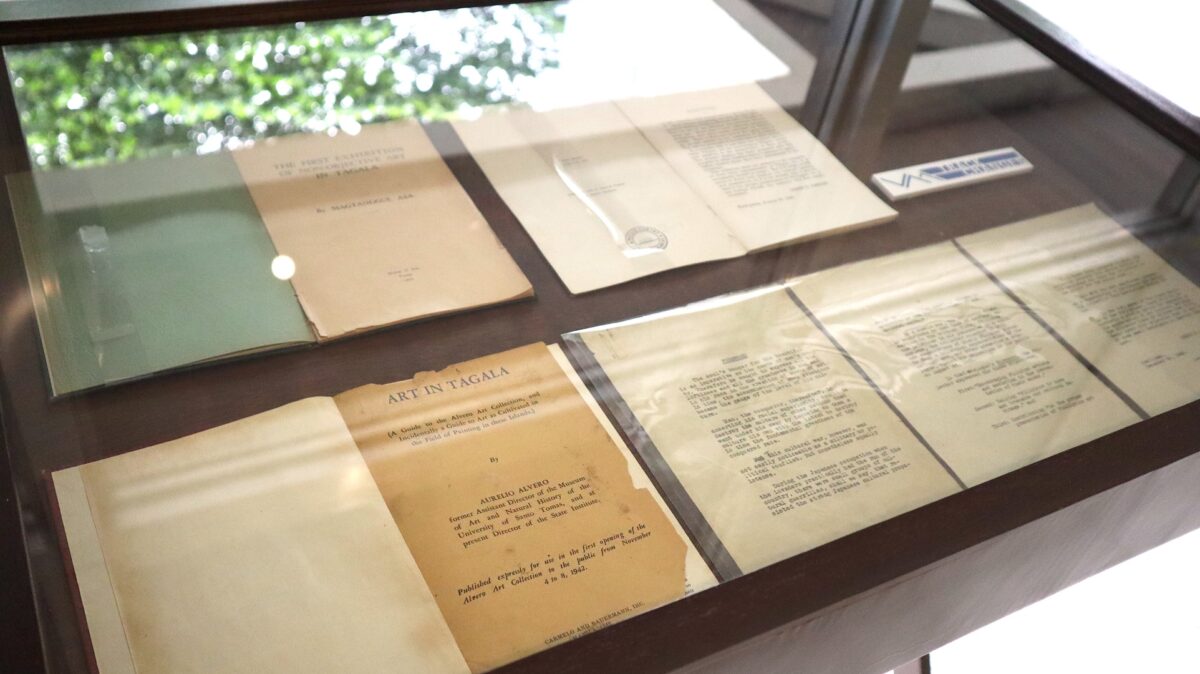

Jorge Vargas aspired to a postwar national culture through an art collection, as stated in the founding papers of the collection. The latter yield references to cultural heritage being vital for a “young Republic” and the logic of art being a kind of “accumulation” that serves as a gauge of a “level of culture.” According to a 1948 document that conceptually forms the basis of the Vargas collection, the pieces are viewed as “representative of a national art.” The first catalogue, published in 1943, spells out the aims of the collection: “‘encouraging Filipino artists and assisting in the presentation of their works’ . . . helping ‘Filipinos to know and treasure our cultural heritage’. . . and . . . contributing ‘to the proper presentation of Philippine art.’”1Document from the Archive collection of the Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Filipiniana Research Center, Manila. Vargas commissioned modernist painter Victorio Edades (1895–1985), who studied architecture and mural-making at the University of Washington in Seattle and worked in a salmon cannery in Alaska, to write the first catalogue of his collection; and Alvero completed a catalogue of his own collection titled Art in Tagala (1942/1944).2See Patrick Flores, ed., The Vargas Collection: Art and Filipiniana (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Filipiniana Research Center, 2020). These efforts may well be the earliest anthologies of art criticism and curatorial writing in the Philippines to the degree that they attempted close readings of works in a collection.

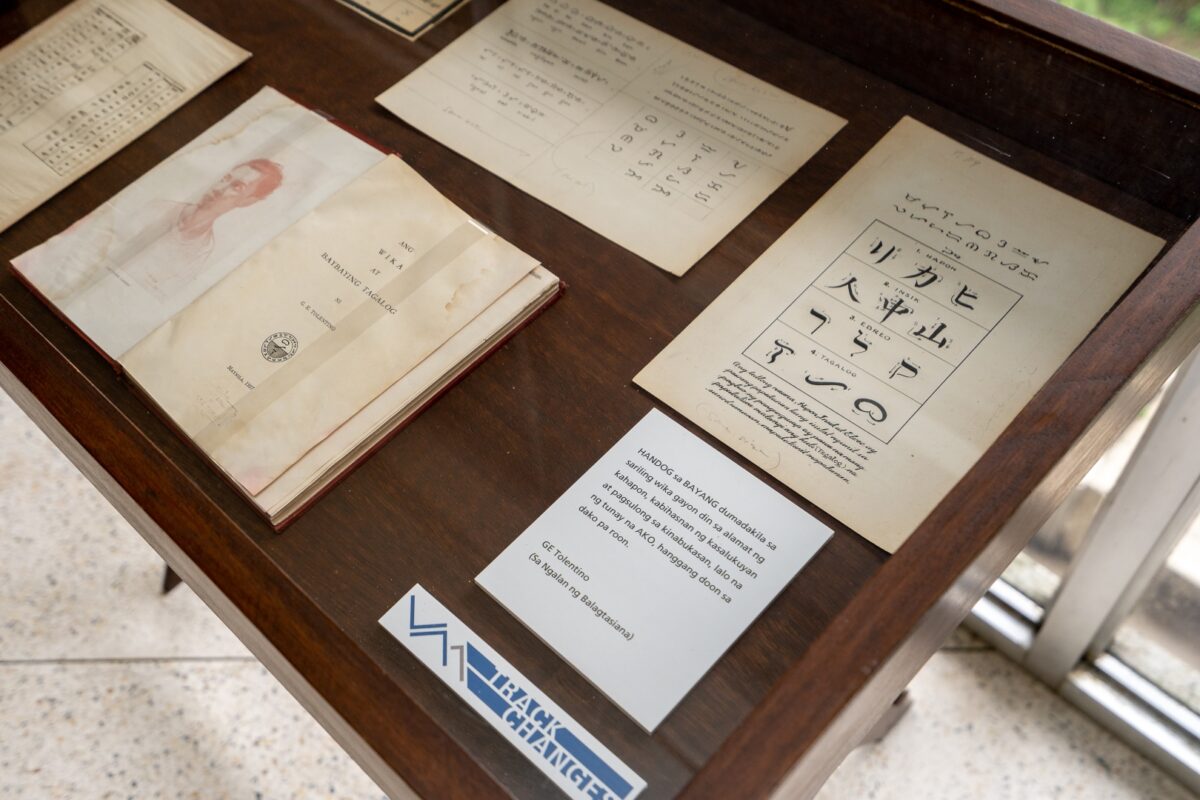

Alvero and Tolentino were nativists who exalted the pre-Hispanic Philippine lifeworld; at the same time, they were decisively (other)worldly, advocates of abstraction and builders of monuments. The term “nativist” is deployed here as a provocation and pertains to the range of articulations that may be considered not-yet or never-to-become colonial (and therefore potentially national or nationalist) or, perhaps, the basis of the exemplary folklore that is the nation, or its afterlife via a new folkloristics in the contemporary. Tolentino was a sculptor of the classical tradition, of the heroic and allegorical kind, and a spiritist who convened séances. He also proffered claims on the Philippine primeval such as its writing system or script, spinning some esoteric codes and wildly transhistorical comparisons.

Jorge Vargas was born into a family that had significant interests in sugar in the central Philippine islands of the Visayas. He was a political figure in the Philippines, its first executive secretary, who served the governments of the United States and Japan from 1935 to 1945. Apart from playing a vital role in American bureaucracy with various portfolios including defense and agriculture, Vargas was invested in the scouting movement, international sports, and the collecting of a gamut of things that, from art to ashtrays, included stamps, coins, photographs, books, and documents, inter alia. He was accused of conniving with the Japanese and later convicted, only to be absolved by the postwar government. He donated his collection to the University of the Philippines, which opened the museum in his name in 1987.

Kept in the vitrines of Track Changes are important texts that tend to inflect the trope of the Philippine bildung. Tolentino’s excursus references a deep past, an ancient ethnic and racial community lying beyond the strictly colonial and imperialist civilization. For instance, in Ang Wika at Baybaying Tagalog (The Language and Script of Tagalog, 1937), he unfolds an almost encyclopedic account of the Philippines through the different systems of knowledge, describing flora, fauna, and people in lofty and idiosyncratic Tagalog, an ethnolinguistic marker of communities around the capital of Manila.3See Guillermo Tolentino, Ang Wika at Baybaying Tagalog ([Manila]: n.p., 1937). Tolentino illustrated some of the pages, including the one imagining how the Tower of Babel might have looked from an interplanetary perspective and in the context of the birth of Tagalog as one of the world’s languages.

Alvero, who opened his collection to the public in 1942, was born to intellectuals. His father was the painter and interior decorator Emilio Alvero (1886–1955), and his mother was Rosa Sevilla (1879–1954), founder of the Instituto de Mujeres (1900), the first Filipino-run lay Catholic school for women. He was an accomplished orator and took up law and education simultaneously. He was a poet and taught English, history, and the Tagalog language. He was tried as a Japanese collaborator and imprisoned from 1945 to 1947 and from 1950 to 1952. He cofounded the Young Philippines, a fringe nationalist party of the 1930s advocating that “The Political Salvation of the World Lies in Dictatorship Rather than Democracy.” Alvero founded a “quasi-fascist, blue-shirted” organization that was modeled on groups in Germany, Italy, and Spain.4Grant K. Goodman, “Aurelio Alvero: Traitor or Patriot?,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27, no. 1 (1996): 96, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20071760. He went by the name of Magtanggul Asa, which in the local language means “Defending Hope,” and wrote prodigiously on Philippine culture. A case deserving closer study is the monograph titled The First Exhibition of Non-Objective Art in Tagala written in 1954 in Manila, in which he theorizes the rubric of the “non-objective” based on the First Non-Objective Art Exhibition in the Philippines, which opened in 1953 at the modernist nerve center in postwar Manila, the Philippine Art Gallery. Here, he would realign the idiom of western abstraction twice: first through the term “non-objective” and second through “Tagala,” a reference to the dominant ethnic society in the country that is appropriated presumably as an alternative to the colonial appellation of the archipelago, which is the Philippines, the genealogy of Filipiniana. With Alvero and Tolentino looming in the mindset of Vargas, the absolute and the occult alternate with the self-conscious and the internationalist to conjure the fantasy of the modern.

Alongside documents related to Vargas, Alvero, and Tolentino, the vitrines also contain visual material from the Japanese occupying forces that portray the Americans as murderous, while promising social stability and prosperity through the banking system, health service, and a market economy under their auspices. Curiously, in their illustrations, which are veritable wartime propaganda, the template is American comics and editorial cartoons, thus indicating a persistence of American popular visuality across colonial cultures.

To discuss Vargas, Tolentino, and Alvero as an ensemble is to anticipate a theoretical and historiographic framework of the Philippine modern that considers the aesthetic, artifactual, and discursive implications of the archival material inscribed in or ornamenting the collection. What might be offered here concomitantly is a method that contemplates the postcolonial modern through a paracuratorial visibility. In this regard, the modern is not singularly intuited as a mode of progress or criticality; like the vitrines in Track Changes, this modern is, as alluded to earlier, offhand. For the ethos of Vargas insisted on a certain pleasure in appreciating the distracting collectible, perhaps an elaboration of the desire to belong to an abstract collective.

The term “kawilihan” is key. Kawilihan was the name of Vargas’s residential complex and the site of the collection before its transfer to the university. It roughly translates as fascination, distraction, or absorption. It shapes the time and pursuit of leisure, even of reverie. The complex was imagined as Pleasantville and was part of the development of the suburbs of Manila. It had a garden where Vargas raised vegetables, chickens, and pigs, and ample spaces where he hosted costume parties. Besides being a concept-work, kawilihan was also real estate, the land that bought and preserved the art.

The care and thoughtfulness that sustained fascination and the longing for culture would not have found its distinct institutional framework had Vargas not settled on an intellectual scheme that braided culture and nation, not to mention art and garden. It was a scheme seen within the context of fondness for materials in a collection thriving on heterogeneity and later subjected to analysis in a university museum. Across these interactions, the collection would feed into a life of ferment, speculation, and scholarship. These three impulses of fascination, culture, and university animate the collecting instinct of Vargas and the collection. The phrase “university museum” holds two of modernity’s most consummate bureaucracies: the university and the museum, from which stem the prospects of enlightenment and radical epistemology through knowing and sensing. The alternation between homegrown joy and critical institution is instructive.

The joy derives from kawilihan. It is at once residence, collection, museum. Its root “wili” is also attentiveness, interest, penchant, liking, pleasure, enjoyment. In the early lexicon, it straddles between afección (in Juan de Noceda and Pedro San Lucar), a profound, deep-seated affection on the one hand, and afición (in Pedro San Buenaventura), a habit, inclination, talent, or an enthusiasm on the other. These words gravitate toward “love”; in one Filipino translation of “wili,” it is considered “mataos na pagmamahal,” or a lofty devotion to a beloved.5Juan José de Noceda et al., Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala (1754; Manila: Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, 2013), 585. If kawilihan as a structure of feeling hangs over a particular sensitivity to a precious belonging, then it is a cognate of the ethos of care and inevitably of curation in the sense of a possession being under the care or in the custody of, or of curiosity, the inquisitiveness about things. Because the state of kawilihan or the condition of wili is absorption, love becomes a discursive articulation of the word: the collector, or lover, loses the self, which is absorbed in the collection.

In the Pedro Serrano Laktaw dictionary, the absorbed subject is an “aficionado, apegado, encariñado,” that is, generally attached, and a connoisseur. Such cultivated attachment and connoisseurship are mediated by an object of desire. The example of the lexicographer is intriguingly allegorical and potentially moral: “Hindi mawiwili ang aso, / kundi binibigyan nang buto.”6Pedro Serrano Laktaw, Diccionario Hispano-Tagálog (Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispanica, 1914), unpaginated. The dog will not be engaged if not given a bone. Wili, therefore, hinges the subject to the object for it to be distracted.

Criticality informs the second aspect, specifically how the conceptualization of culture and the state, or how the state represents the polity through culture, or the ethical necessity of representativeness for a common image of an ethical community that professes the symbolic birthright of a tradition.7See David Lloyd and Paul Thomas, “Culture and Society or ‘Culture and the State’?,” Social Text 30 (1992): 27–56, https://doi.org/10.2307/466465. To be more concrete in the Philippine historical context, the trope of the American Commonwealth and the Japanese Greater Co-Prosperity Sphere speaks to a collective and expansionist imaginary rooted in colonial history. And the sui generis Vargas was right at the center of these projects and at the same time the collector of the evolving Filipiniana of the Philippines. No other figure in Philippine history rivals his acumen and dexterity in terms of the country’s political and aesthetic education. The historian Teodoro Agoncillo, who wrote a detailed account of the Vargas collaboration case, opines that the “collaboration question was . . . the brainchild of the Americans who, acting under the pressure of the prevailing war psychosis, dictated to the hapless Filipinos what they should and should not do or think in relation to the incidents and accidents of the war.”8Teodoro A. Agoncillo, The Burden of Proof: The Vargas-Laurel Collaboration Case (Manila: University of the Philippines Press, 1984), x.

What Track Changes does is to create a relationality between the historiography, which is also the museology, of colonial and modern art and the curatorial supplement that is not programmatic or thematic, but rather contingent and tropic. It insinuates itself from within the institution and beside, or within reach of, the displayed collection to hopefully choreograph, or subtly incite, the frisson of “situated knowledge” across the varia or corpora in the room. In other words, the paracuratorial in this instance coordinates, hints at, a cognitive mapping of things in a tentative totality without lapsing into ideological iconography or art-historical repetition. The “para-” turns out to also be “proto-” in that it reveals symptoms of the museological unconscious of Vargas as well as the apparatus that enabled the collection to cohere and then ramify across temporalities through curatorial activation. The native, the national, and the non-objective suffuse this utterance of the modern—all caught up in contradictions but also pointing to a third moment beyond the dualisms that underlie all stylizations of coloniality and its attendant class-, gender-, race-continuous discriminations. Track Changes proves to be a viable intersectional site that cannot be quickly co-opted by narrow specialization and the positivisms it attracts.

The native, the national, and the non-objective initiate a relay between expressions of the subjectivity that is the Philippine, construed as a figurine and not an identity. The latter dilates across the said three registers in which various imaginaries coalesce to generate particular phases, and plasticities, of modernity: the supposed authenticity of the indigenous (the native), the idealized cultural character of postcolonial autonomy (the national), and the eccentric entitlement to a transcultural and international abstraction (the non-objective) in which all empirical and rational references are banished as if to perform the purity of the native and the melancholic hubris of the national. In a certain way, the Philippine is all of these, condensing in the acquisitive personas of Vargas, Tolentino, and Alvero, who communed with the archaic, the multitude, and the dead—all taken by liberal sympathies, cabinets of curiosity of their own. In this sequence of categories, the notion of the modern becomes exceptionally complex, interpellated by the difficult desires of belonging, and not belonging, to the aesthetic polity of the colonial western by sketching out a cognate genealogy of the Kantian sensus communis: the bodies of willful subjects, which include the collector, the collection, and the culture. This can only be the very groundwork of the museum, its curatorial substrate, when it renders the art ambiguously present in its space, “derived from distractive experience” and turned into an “abstraction of bits of the world.”9Richard Shiff, Richard Shiff: Writing After Art; Essays on Modern and Contemporary Artists (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2023), 307. Modern art critic Richard Shiff brings distraction, abstraction, and the (non)objective together rhythmically: as the art is grasped so does it “draw away” and “draw apart” from how it is sensed as actually existing and how its becoming real is not only poignantly, but also punctually prefigured.10Shiff, Writing After Art, 298.

To end with another distraction: In 2022, the Philippine government asked the Vargas Museum to temporarily keep and curate the collection of about five hundred pieces from the collection of Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled the country from 1965 to 1986, at a time when the couple’s son Ferdinand Marcos Jr. had become president. The items in the collection comprise paintings on canvas, glass, and wood. They are crafted from the tradition of lacquer, egg tempera and copper, and the ornament of gold leaf, among other mediums. These objects are paintings from the late Gothic and Rococo periods in Italy, reverse glass paintings from former Yugoslavia of folk-fantastic style and called “naif” in Southeast Europe, and lacquer vanity cases and religious icons from Russia. The Marcos government was hailed as developmentalist and cosmopolitan but was deposed by a popular uprising in the wake of autocracy and allegedly massive thieving.

While not cohabiting with the display of the collection and Track Changes, the Marcos collection finds its place alongside the Vargas Collection guided by a kindred paracuratorial sensibility. The task of a university museum is to invite a mindful and urgent study of these objects as well as the tricky lives of Vargas and Ferdinand Marcos, both of whom were enmeshed in the history of colonialism, the formation of nation-states, the accumulation of wealth, and the status itself of objects in collections. With their contentious imbrication as the ecology, essential questions may be revisited: What is an object? How does it become property or patrimony? Why is it in the world, why are we around it, and what do we as subjects do about it?

When the initiatory and coincidental Track Changes asks these same questions, digressively and not aggressively or even transgressively, it drags and pulls the museum in different directions, paracuratorially. As the title “Track Changes” suggests, it traces the indicia of amendments to the text, the writing itself of difference—or the difference finally of curatorial writing.

- 1Document from the Archive collection of the Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Filipiniana Research Center, Manila.

- 2See Patrick Flores, ed., The Vargas Collection: Art and Filipiniana (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Jorge B. Vargas Museum and Filipiniana Research Center, 2020).

- 3See Guillermo Tolentino, Ang Wika at Baybaying Tagalog ([Manila]: n.p., 1937).

- 4Grant K. Goodman, “Aurelio Alvero: Traitor or Patriot?,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27, no. 1 (1996): 96, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20071760.

- 5Juan José de Noceda et al., Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala (1754; Manila: Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, 2013), 585.

- 6Pedro Serrano Laktaw, Diccionario Hispano-Tagálog (Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispanica, 1914), unpaginated.

- 7See David Lloyd and Paul Thomas, “Culture and Society or ‘Culture and the State’?,” Social Text 30 (1992): 27–56, https://doi.org/10.2307/466465.

- 8Teodoro A. Agoncillo, The Burden of Proof: The Vargas-Laurel Collaboration Case (Manila: University of the Philippines Press, 1984), x.

- 9Richard Shiff, Richard Shiff: Writing After Art; Essays on Modern and Contemporary Artists (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2023), 307.

- 10Shiff, Writing After Art, 298.