Articulations of the relational have been shifting in parallel with the recent turn in global contemporary art toward validating ecological and indigenous practices. This shift invites a consideration of what exactly constitutes the relational among artistic and curatorial efforts within the global contemporary. And among Southeast Asian exemplars, the multimedia practice of artist Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook (born 1957, Thailand) comes to mind as a rich prompt via which to think about the nuances, complications, or possibilities in the relational.

Hinting at such nuances, Roger Nelson and Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol’s essay accompanying a recent translation of Araya’s writing proposes the neologism “transunitary” to characterize Araya’s practice: “It is between and across and beyond its many parts and modes. . . . It is a singular practice whose polysemy and sometimes almost dissociative polyvocality circles around ethical, existential concerns.”1Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol and Roger Nelson, “Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: Between and Beyond (He and She),” in I Am An Artist (He Said),by Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, ed. Roger Nelson and Chanon Kenji Praepipatmonkol, trans. Kong Rithdee (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2022), 427.It is striking to note that the thematically diverse range of critical and curatorial discourses on Araya’s practice converge around each of two poles. The first implies that her artistic evocation of the relational hinges on a certain similarity in existential conditions. This does not imply shared suffering through common experiences or circumstances, but rather affective solidarity through proximate conditions of existential marginality—for instance, the similarities between female subjects in patriarchal gender regimes, or those between the lives of powerless, marginalized humans and the lives of animals dependent on human care or vulnerable to human violence. 2See, for example, Arnika Fuhrmann, Ghostly Desire: Queer Sexuality & Vernacular Buddhism in Contemporary Thai Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 160–84; Filipa Ramos, “Other Faces: Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Interspecies Engagements,” Afterall 47 (Spring/Summer 2019): 208–24; Clare Veal, “Water Is Never Still: Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Sculptural and Installation Practice,’ ibid., 178–207; and John Clark, Clare Veal, and Judha Su, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: Storytellers of the Town, exh. cat. (Sydney, NSW: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2014). Meanwhile, the second discursive tendency dwells on the radical independence, singularity, and intransigence of Araya’s practice, thereby associating the relational with the potential in dissociation, that is, with the artist’s agency in terms of establishing distance from or separating from her immediate artistic and social contexts.3See, for example, Sayan Daengklom, “Outline of the Genesis (Series 1: The Final Test),” in The Two Planets: Village and Elsewhere,exh. cat. (New York: Tyler Rollins Fine Art, 2012); Chanon Kenji and Nelson, “Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: Between and Beyond (He and She),” 424–68; and May Adadol Ingawanij, “Art’s Potentiality Revisited: Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Late Style and Chiang Mai Social Installation,” in Artist-to-Artist: Independent Art Festivals in Chiang Mai, 1992–98,by David Teh et al., Exhibition Histories (London: Afterall in association with Asia Art Archive and the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, 2018), 252–63.

Here, I would like to think about the question of the relational in contemporary artistic practice from another angle, one more explicitly attentive to encounters or entanglements with difference.4My thinking on the question of relations in Araya’s practice was triggered by reading Marilyn Strathern, Relations: An Anthropological Account (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020). I detour to the artist’s usage of the cinematic tableau as a method of framing, displaying, and addressing difference. In the context of contemporary moving image practices, the tableau has a broader, less traditional meaning than that of restaging an artwork. The cinematic tableau can instead be understood as a compositional form that draws attention to the displaying and viewing of images.

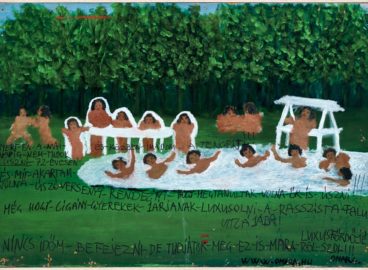

Araya explores the relational potential of the tableau most fully in two video installation series: The Two Planets (2008) and Village and Elsewhere (2011), both of which are composed of short audiovisual vignettes that are usually exhibited as multichannel video and photographic installations. The individual works in each series are almost identical in terms of visual composition. Araya re-situates one or two large-scale, ostentatiously gold-framed reproductions of famous western paintings in outdoor or neighborhood spaces in the rural outskirts of the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai. The video camera frames these reproductions and their visually associative physical surroundings in a straight-on shot. On-screen, the framed reproductions are frontally displayed in the background. In the foreground, small groups of people are visible from the back, and their murmurings, chatter, gossip, speculations, and digressions as they look at the reproductions audible. A reproduction of the work by Vincent van Gogh of a man and woman asleep by a haystack is placed in a lush green field of banana trees and other crops in Van Gogh’s The Midday Sleep and the Thai Villagers (2008; fig. 1); a reproduction of a painting by Edouard Manet of picnickers hangs in a bamboo wood in Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass and the Thai Villagers (2008); and a reproduction of a painting of peasant women by Jean-François Millet is beautifully positioned at the edge of a lake, seemingly suspended above the calm surface of the water in Millet’s The Gleaners and the Thai Farmers (2008). Inside the prayer hall of a neighborhood Buddhist temple, its wooden panels painted burgundy, two enormous and provocative reproductions are placed side by side at one end of the hall; behind them on the wall are brightly colored murals displaying scenes from Theravada tales (Village and Elsewhere: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, Jeff Koons’s Untitled and Thai Villagers, 2011).

In each of these audiovisual vignettes, the duration of the scene displayed approximates the duration of spectatorship by a figural group whose faces we do not see. The visualization of the group signifies “Thai Villagers,” or “Thai Farmers,” transfiguring people who, in everyday life, live in the same suburb as the artist. In each tableau, the group is sitting on the ground, their backs to us, facing the framed reproduction. The shortest of these videos are nearly ten minutes, and the longer ones about twenty-five. Someone comments on a detail that strikes them about the picture in the frame. Another person observes something about this face or that body, this plant, that tool, this hat, or that dish. The group amuses itself, speculating wildly on the backstory in the displayed scene. Sometimes they prod one another to dart up to the framed picture and point out a small detail—or to caress the image of a face, the skin, a body part. With the van Gogh reproduction, the group contemplates the placement of the sickle, the number of wheels on the wooden cart, the total number of oxen legs visible, and the casting of the sunlight on the haystack, all in order to decipher winning lottery numbers. Their conversation flows easily, often straying from the framed reproduction to random neighborhood gossip. Each video is unscripted and staged as a one-take piece using a static shot. The editing is minimal, involving discreet jump cuts to crop out of parts of the conversation without changing the visual composition, giving the impression that the vignettes are displaying spectatorial experiences in real time.

Film theoretical scholarship on the tableau tends to imply a continuation of modernist cinema and museum spectatorship.5See Brigitte Peucker, The Material Image: Art and the Real in Film (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006); and Agnes Petho, “The Image, Alone: Photography, Painting and the Tableau Aesthetic in Post-Cinema,” Cinéma & Cie International Film Studies Journal 25, no. 25 (Fall 2015): 2665–3071. This modernist genealogy continues to exert an influence over present-day thinking about contemporary art cinema and the moving image. Here, contemplation remains a persistent marker of the value of spectatorial experience, along with the conception of the apparatus of display that situates the spectator as the solitary beholder of the artwork. Agnes Petho, for instance, observes that the contemporary “tableau-film” 6Petho, “The Image, Alone,” 2863., is, in effect, a continuation of the modernist apparatus for the display of artwork. That is, the artwork is presented for the eyes of the spectator, for contemplation by its beholder. In order for the spectator “to comprehend the picture as a whole,” the work is “displayed in a manner that visibly separates it from the surrounding space,” implying the spectatorial experience is one of intimate, solitary beholding.7Petho, “The Image, Alone,” 2932–33

Petho differentiates this mode of spectatorship from the more familiar model in which the filmic tableau represents an occasional, exhibitionistic moment of suspension of narrative flow. Her proposition concerning the spectatorial mode of the contemporary tableau-film helps us to grasp the precision with which Araya’s series decenters that model. Rather than reproducing the ideology of the cinematic tableau that is indebted to the genealogy of western modernist art history, the form of display of The Two Planets and Village and Elsewhere instead constellates two incommensurable spectatorial models. The apparatus of contemplative beholding is figured, frontally displayed, and simultaneously entwined with another genealogy of displaying, spectating, and experiencing images, one anchored in improvisatory, social, and participatory interactions.

Village and Elsewhere: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, Jeff Koons’s Untitled and Thai Villagers (fig. 3) is an especially suggestive example in this regard. The framed scene takes place inside rather than outside, in the public space of the prayer hall of a Buddhist temple. In the background of the tableau shot, we see an enormous gold-framed reproduction of an untitled painting by Jeff Koons that is displayed frontally on the left side of the screen. Beside it, toward the right side of the screen, there is a reproduction of a painting by Artemisia Gentileschi, which is encased in a matching gold frame equal in size to the one framing Koons’s work. In the foreground, there are several rows of lively spectator-figures, children and neatly dressed older women—including Araya herself—all of whom are sitting with their backs to the camera on a fandango pink carpet facing the two reproductions. Unlike in most of the other works in the series, a figure stands next to the framed reproductions and faces the camera. He is a Buddhist monk who, for the duration of the video, delivers a humorous, didactic sermon on the third Buddhist precept, the prohibition of sexual misconduct, using the images as visual aids. The response of his audience of unruly children and aunties veers between raucous opining and gleefully digressive and associative interpretations of details in the images to chanting enthusiastic replies by rote. The last group of visible figures in this work are sāmaṇeras, or novice monks, and dogs of different sizes, whose errant wandering off- and on-screen during the unusual sermon disarrays the loose geometric lines of the tableau.

This improvisatory and participatory spectatorship recalls another genealogy of moving-image exhibition: the live narration of films. As with a number of other global majority cinematic cultures throughout the twentieth century, such practices have been the predominant mode of film exhibition and spectatorship in Thailand. Film “versioning” artists toured the country and strayed into borderlands, performing live or as-live vocal improvisations accompanying film projection.8See May Adadol Ingawanij, “Itinerant Cinematic Practices In and Around Thailand During the Cold War,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 2, no. 1 (March 2018): 9–41; and “Mother India in Six Voices: Melodrama, Voice Performance, and Indian Films in Siam,” BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies 3, no. 2 (July 2012): 99–121. They served as human mediators of film projection performances whose agency in making films come to life, and whose translation of highly mobile, reproducible images into utterances addressed to specific audience congregations, constituted another ground from which to re-pose questions concerning cinema’s ontology and its historical or possible modes of spectatorship. In Araya’s staged tableau, the monk-narrator seems to channel the ancestral figure of the film “versionist.” His improvisatory montaging of a story sequence from Koons to Gentileschi resources his fabulation of a morality tale concerning the spectacular punishment of an adulterous man. The duration of display of this tableau makes perceptible how the monk’s sermon thrives on the sociality and unpredictability of spectatorial energy. To spectate here is to participate in the liveness of improvisation, asserting, exchanging, interjecting, and derailing meaning. Presenting the monk’s versioning and installing traveling, reproducible images inside the temple compound should not be understood in blunt terms as gestures of artistic disruption to the institutional and affective functioning of this place of worship. It is worth recalling that the Buddhist temple ground in Thailand and elsewhere has historically played host to, and certainly continues to host, wide-ranging forms of public celebrations and festivities including itinerant film projection.

In one of her many pieces of writing connecting her visual and textual practice, Araya tells a story of how she came upon the idea to make Village and Elsewhere and The Two Planets:

เป็นในเช้าตรู่วันหนี่ง ฉันนั่งอยู่ในห้องอาหารกว้างของโรงแรมในเมืองหลวงหนึ่งของยุโรป มีกาแฟร้อนบนโต๊ขณะมองดูหิมะตกขาวบนถนนในเมืองและลานกว้าง ฉันนั่งดูเมืองสลับไปกับอ่านบทความที่อ่านค้างอยู่ว่าด้วยศิลปะอาเซียน ท่อนหนึ่งของบทความพูดถึงการพัฒนาศิลปะของเอเชียจะเป็นไปได้จำต้องได้รับการวิจารณ์ที่แหลมคมจาภายนอก หมายถึงยุโรปและที่อื่นๆ

ด้วยเหตุที่ชีวิตฉันแวดล้อมไปด้วยสองสิ่งอย่างซึ่งต่างกันคือ ศิลปะซึ่งถูกดูแลดีราวกับจะไม่มีวันตาย กับ อีกอย่างคือเมื่อฉันย้ายออกจากเมืองมาอยู่ในชนบท, ภาพธรรมชาติ การเกิดและตายง่ายๆ ของคนในหมู่บ้าน

ฉันวางสองอย่างไว้คู่กัน ศิลปะชิ้นเอกของโลกกับ ชาวนา ชาวสวน สวนทางกับประโยคเคยอ่านข้างต้น

Early one morning, I was seated in a large restaurant inside a hotel, somewhere in a European capital city, with hot coffee on the table. The streets and square outside were covered in pristine white snow. I alternated between watching the world go by and reading an article I had started on ASEAN art. At one point, the author asserts that Asian art can only develop if artists are stimulated by sharp external criticism, meaning from Europe or elsewhere.

I exist in two different environments. One is the world in which artworks are so well looked after they seem immortal. When I moved out of the city, I encountered the other world, a world of nature and of birth and death without fanfare of people in the village.

I placed these two beings together—the world’s renowned artwork, and the farmers—reversing the logic prescribed in the sentence I had read.9 Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: In this circumstance, the sole object of attention should be the treachery of the moon, exh. cat. (Bangkok: ARDEL Gallery of Modern Art, 2009), unpaginated. My translation.

Art historian Sayan Daengklom cautions against the reductiveness of reading Araya’s tableaux as a reversing of the Eurocentric mentality expressed in the article she had come across: the provision of an opportunity for the native to talk back and to criticize famous western artworks.10Sayan, “Outline of the Genesis (Series 1: The Final Test),” 94. Another parallel logic, that of inclusion, likewise meets a dead end when used merely to endorse the socially and symbolically privileged artist for making artworks that apparently endow voice and visibility to the underrepresented. Equally reductive would be to conclude that Araya made these tableaux by manipulating specific groups of people with her symbolic privileges: Araya the artist-academic luring unsuspecting villagers and farmers into her frame in order to expose their ignorance about western modernist art and its spectatorial and museological conventions.

How then to think differently about the relational form of Araya’s tableaux—their constellating, staging, and superimposing of incommensurable modes of display and spectatorship? The logic of display and address in Araya’s series might be thought of as a twist on Jacques Rancière’s proposition concerning the potentiality of art in the aesthetic regime.11Jacques Rancière, “Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community,” in The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2009), 51–82. In his argument, the potential efficacy of this regime is premised on dissociating the artwork’s form from its presumed effect. It also implies a conception of community structured in separation and asynchrony. Aesthetic community in this definition concerns the common capacity of every person to experience art in dissimilar and unpredictable ways, and it implies community in absentia, as the speculative future. While differentiating his proposition from western modernist ideas regarding the autonomy of artwork and aesthetic experience, Rancière’s characterization of the potentiality of the aesthetic break still rests on an assumption of the necessary solitude of aesthetic experience. His proposition tends to imply that, at best, artistic works are efforts that, in their very form, explore “the very tension between the apart and the together . . . either by questioning the ways in which the community is tentatively produced or by exploring the potential of community entailed in separation itself.”12Rancière, “Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community,” 78. What if the potentiality of the aesthetic regime—its unpredictability—is less a matter of the separation/solitude of the beholder in their aesthetic experiencing than of the sensorial and perceptual encountering of difference? Here, Édouard Glissant’s proposition regarding the necessity of the poetics of relations in what he calls the “chaos-world” provides a compelling counterpoint. “Chaos-world” is Glissant’s name for the totality of the contemporary world, in which inhabitants live within multiple temporalities and do so within a drastically accelerated time of intercultural contacts and connections. The chaos-world is “the shock, the intertwining, the repulsions, attractions, complicities, oppositions and conflicts between the cultures of peoples.”13Édouard Glissant, ‘The Chaos-world: Towards an Aesthetic of Relation,’ in Introduction to a Poetics of Diversity, trans. Celia Britton (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020), 54. Unpredictability is likewise a foundational value in Glissant’s conception of the potential of the aesthetic or the poetic. Yet, unlike Ranciere’s definition of the aesthetic regime, Glissant posits the relational as a situated imagining, opening out from one’s locality and experiencing the extensiveness, immeasurability, openness, and unpredictability of connecting and colliding with others near and far in the totality of the chaos-world. Here, the relational becomes the sensation and the potential of entangling in radically different or incommensurable forms, modes, and beings. With this in mind, I would like to end by drawing attention to how Araya’s tableaux stage encounters with the foreign, and entangle us, the off-screen spectators, in the time-space of the mise en abyme.

The tableau display of the gold-framed reproductions references and aggrandizes museum conventions of hanging and presenting artworks on walls, an exhibition apparatus that lays claim to addressing everyone. Yet the spectators in The Two Planets and Village and Elsewhere exceed the boundary of that universalizing assertion with their actualization of what, following Elaine Castillo, we might call the spectatorship of the unintended.14Elaine Castillo, “Reading Teaches Us Empathy and Other Fictions,” in How to Read Now (New York: Viking, 2022), 65. Thank you to Cristian Tablazon for telling me about Castillo’s idea. At the same time, their encounters with the reproductions take place in spaces that do not cohere with the museological value of suspending the time and space of daily life. The “Thai Villagers” and “Thai Farmers” in Araya’s tableaux are shown engaging with framed reproductions of art in neighborhood spaces—the local field, temple, and bamboo forest. The spectatorship of the unintended that they enact is a kind of unruly hosting, an extending of hospitality to the foreign, an unpredictable engagement with mobile artifacts from distant lands, cultures, and times.

An iteration of Village and Elsewhere: Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, Jeff Koons’s Untitled and Thai Villagers at 100 Tonson Gallery (Bangkok, 13 October 2011 – 31 January 2012) reproduces and re-situates the audiovisual vignette in the format of a single-channel projection of a video within a video. In this example, the projected display shows the sermon video playing on a television screen inside what appears to be a Japanese Buddhist temple and being watched by a small group of monks seated to one side of the television screen. Here, Araya quite explicitly draws attention to the mise-en-abyme structure of the work, highlighting its function as a method of spectatorial entanglement.15Sayan and Veal also observe Araya’s creation of mise en abimes. See Sayan, “Outline of the Genesis (Series 1: The Final Test),” 112; and Veal, “‘Water Is Never Still,” 198. Each of us, as off-screen spectators, becomes ensnared as the additional figure in the group, the incidental commencer of another space of viewing-participation, situated beyond and “behind” the arrayed bodies of the aunties, children, and dogs on the TV screen, and the monks in Japan whose profiles fill the foreground. In this way, Araya’s installation undoes the separation between the work as an object of viewing, and the spectator as a subject of vision. The mise-en-abyme structure of this and other works in her tableaux creates a preposterous effect of vacillation between the vision of the spectating subject and the spectator as object.

My usage of the notion of the preposterous is inspired by Mieke Bal’s method of theoretic fiction. Bal analyzes the relationship between the work of Caravaggio and that of the contemporary artists who “quote” him, doing so in such a way as to conceptualize the method of “preposterous history” and its accompanying contemporary baroque epistemology.16Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). This historiographic method runs counter to art history’s traditional historiographic method, in which the relationship between historical and contemporary works of art is one of the former’s influence over the latter. Bal proposes instead that contemporary artistic works constitute the starting point with which to engage with, understand, or reenvision historical works, and in so doing, to grasp precisely the historical characteristics of those works from the concerns and vantage points of the present. This is the “preposterousness” in question, a dynamic of inquiry constituting a kind of baroque vision characterized by a “vacillation between the subject and object of that vision and which changes the status of both.”17Bal, Quoting Caravaggio, 7. Embracing the necessity of reestablishing the terms of relations between entities, acknowledging their singularity while asserting their contemporaneous status, this baroque sense of preposterousness is highly applicable to Araya’s practice. Focusing on Araya’s use of the tableau enables us to better grasp the way the artist makes relational forms. Insofar as her work entangles beings, species, roles, and worlds—the living and the dead, women and dogs, the artworld and the village, the spectator, the participant, and the artist—it might be described, to riff on Nelson and Chanon Kenji’s neologism, as a kind of trans-relational method performing the duration and movement of associating radically different beings and incommensurable worlds. What is so significant about Araya’s practice lies here, in the performing and framing of relations of radically different beings, and of incommensurable and yet contemporaneous entities, in ways that are preposterous, wildly disorientating, and fully lived.

- 1Chanon Kenji Praepipatmongkol and Roger Nelson, “Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: Between and Beyond (He and She),” in I Am An Artist (He Said),by Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, ed. Roger Nelson and Chanon Kenji Praepipatmonkol, trans. Kong Rithdee (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2022), 427.

- 2See, for example, Arnika Fuhrmann, Ghostly Desire: Queer Sexuality & Vernacular Buddhism in Contemporary Thai Cinema (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 160–84; Filipa Ramos, “Other Faces: Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Interspecies Engagements,” Afterall 47 (Spring/Summer 2019): 208–24; Clare Veal, “Water Is Never Still: Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Sculptural and Installation Practice,’ ibid., 178–207; and John Clark, Clare Veal, and Judha Su, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: Storytellers of the Town, exh. cat. (Sydney, NSW: 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, 2014).

- 3See, for example, Sayan Daengklom, “Outline of the Genesis (Series 1: The Final Test),” in The Two Planets: Village and Elsewhere,exh. cat. (New York: Tyler Rollins Fine Art, 2012); Chanon Kenji and Nelson, “Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: Between and Beyond (He and She),” 424–68; and May Adadol Ingawanij, “Art’s Potentiality Revisited: Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s Late Style and Chiang Mai Social Installation,” in Artist-to-Artist: Independent Art Festivals in Chiang Mai, 1992–98,by David Teh et al., Exhibition Histories (London: Afterall in association with Asia Art Archive and the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, 2018), 252–63.

- 4My thinking on the question of relations in Araya’s practice was triggered by reading Marilyn Strathern, Relations: An Anthropological Account (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020).

- 5See Brigitte Peucker, The Material Image: Art and the Real in Film (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006); and Agnes Petho, “The Image, Alone: Photography, Painting and the Tableau Aesthetic in Post-Cinema,” Cinéma & Cie International Film Studies Journal 25, no. 25 (Fall 2015): 2665–3071.

- 6Petho, “The Image, Alone,” 2863.

- 7Petho, “The Image, Alone,” 2932–33

- 8See May Adadol Ingawanij, “Itinerant Cinematic Practices In and Around Thailand During the Cold War,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia 2, no. 1 (March 2018): 9–41; and “Mother India in Six Voices: Melodrama, Voice Performance, and Indian Films in Siam,” BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies 3, no. 2 (July 2012): 99–121.

- 9Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: In this circumstance, the sole object of attention should be the treachery of the moon, exh. cat. (Bangkok: ARDEL Gallery of Modern Art, 2009), unpaginated. My translation.

- 10Sayan, “Outline of the Genesis (Series 1: The Final Test),” 94.

- 11Jacques Rancière, “Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community,” in The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2009), 51–82.

- 12Rancière, “Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community,” 78.

- 13Édouard Glissant, ‘The Chaos-world: Towards an Aesthetic of Relation,’ in Introduction to a Poetics of Diversity, trans. Celia Britton (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020), 54.

- 14Elaine Castillo, “Reading Teaches Us Empathy and Other Fictions,” in How to Read Now (New York: Viking, 2022), 65. Thank you to Cristian Tablazon for telling me about Castillo’s idea.

- 15Sayan and Veal also observe Araya’s creation of mise en abimes. See Sayan, “Outline of the Genesis (Series 1: The Final Test),” 112; and Veal, “‘Water Is Never Still,” 198.

- 16Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

- 17Bal, Quoting Caravaggio, 7.