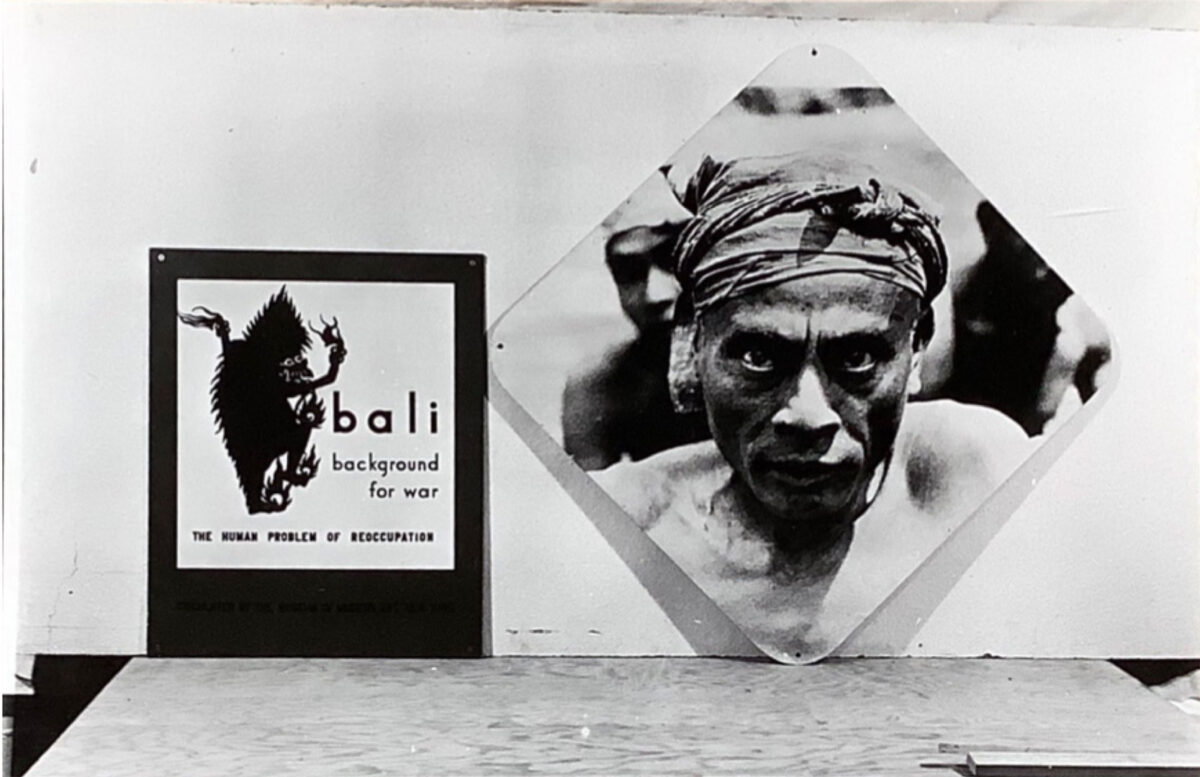

This two-part essay introduces the exhibition Bali, Background for War: The Human Problem of Reoccupation, an exhibition curated by anthropologist and cybernetics pioneer Gregory Bateson at The Museum of Modern Art in 1943. Bali, Background for War was an important exhibition of Southeast Asian modern art history and occupies an exceptional place in the Museum’s institutional history. This second essay traces the wide-ranging infrastructural implications of Bateson’s exhibition from the unrealized Wartime Regional Materials Unit at MoMA to the landscape of foreign capital flows and cultural infrastructure that contributed to the canonization and conceptualization of a Southeast Asian modern art during the Cold War.

Read the first part of the series here.

Anthropologist Gregory Bateson believed that a systematic understanding of other cultures was important for a peaceful postwar world order. He also believed that the museum, particularly The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), was the ideal institution to undertake this work. In MoMA’s press release for the exhibition Bali, Background for War: The Human Problem of Reoccupation (1943), Bateson notes that “there is one common ground between the scientific world of the anthropologist and the world of art: the idea that in some sense the artist expresses himself. The exhibition is based on that idea which, in time of war, may become as grim as a mathematical equation in ballistics.”1The Museum of Modern Art, “Museum of Modern Art Opens Exhibition of Bali, Background for War,” press release [1943], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/895/releases/MOMA_1943_0047_1943-08-10_43810-44.pdf.

Bali, Background for War captured the social science and art networks that were brought together during World War II by the war effort and an institution of modern art. In turn, the exhibition became an important constellation of global history. At MoMA, Bateson’s notion of the museum as a common ground for science, art, and social engineering dovetailed with Bauhaus thought on the shaping of visual culture and perception, leading to a historical confluence of proto-cybernetics, regional thinking, and the New Bauhaus within the modern art museum in the service of military goals and postwar rebuilding. The influence of Bali, Background for War resounded in the postwar years, possibly contributing to the formation and intellectual history of Southeast Asian modern art networks in terms of how the exhibition foreshadows but is also informative in reading the postwar rehabilitation of the US cultural Cold War in Southeast Asia.

During World War II, the Museum executed 38 contracts for various government agencies. Among these contracts and programs, Bateson found work in the Film Library developing cultural intelligence studies of Axis countries through film.2See “John Hay Whitney Announces Museum of Modern Art Will Serve as a Weapon of National Defense,” press release [1941], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/676/releases/MOMA_1941_0015_1941-02-28_41228-14.pdf; and Nathaniel Brennan, “The Cinema Intelligence Apparatus: Gregory Bateson, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, and the Intelligence Work of Film Studies during World War II,” chap. 8 in Cinema’s Military Industrial Complex, ed. Haidee Wasson and Lee Grieveson (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018). While Bateson was not a film specialist per se, it was his work in Bali and his use of still and motion photography in analyzing cultures that attracted the attention of Iris Barry, first curator of MoMA’s Film Library (now the Department of Film), and led to his employment.3See Brennan, “The Cinema Intelligence Apparatus.” Prior to joining the Museum, Bateson believed that MoMA had a specific and important role in the war effort, particularly in producing wartime subjectivities through exhibitions. This resonates with how scholar Fred Turner has described the exhibition-form’s compilation of material and the vistas from which viewers could freely discern cultural patterns and navigate the exhibition as a “democratic surround.”4See Fred Turner, The Democratic Surround: Multimedia & American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013). This experience of moving from image to text, of observation, inference, and deduction, could lead the audience to become more psychologically flexible and democratic in nature.5In this respect, Turner notes in his conceptualization of the surrounds that Bateson and Mead’s work was motivated by addressing the needs of the Allied Forces. On the one hand, Allied soldiers needed information on the enemy and the allied national cultures they would encounter. On the other hand, because of the fighting, they could not send researchers to those places to perform the necessary studies. Thus, Mead and Bateson began to assemble cultural material from overseas and to study what they called “culture at a distance.” See Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942). In this regard, Bali, Background for War was an occasion for viewers “to exercise democratic choice.”6Turner, The Democratic Surround, 74. This was an exhibitionary logic that provided a counterpoint to Nazi Germany’s instrumentalized modes of communication and power associated with fascist propaganda. Turner notes that Mead and other members of the Committee for National Morale, of which Bateson was secretary (while still at MoMA), envisioned the museum as the proper setting for a new kind of propaganda that could nurture both the individual democratic personality and a collective sense of national purpose.7See Turner, The Democratic Surround, 73. See Memorandum on a Proposed Exhibit on Democracy in the Museum of Modern Art, box 5, folder 1, Exhibits, Democracy, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

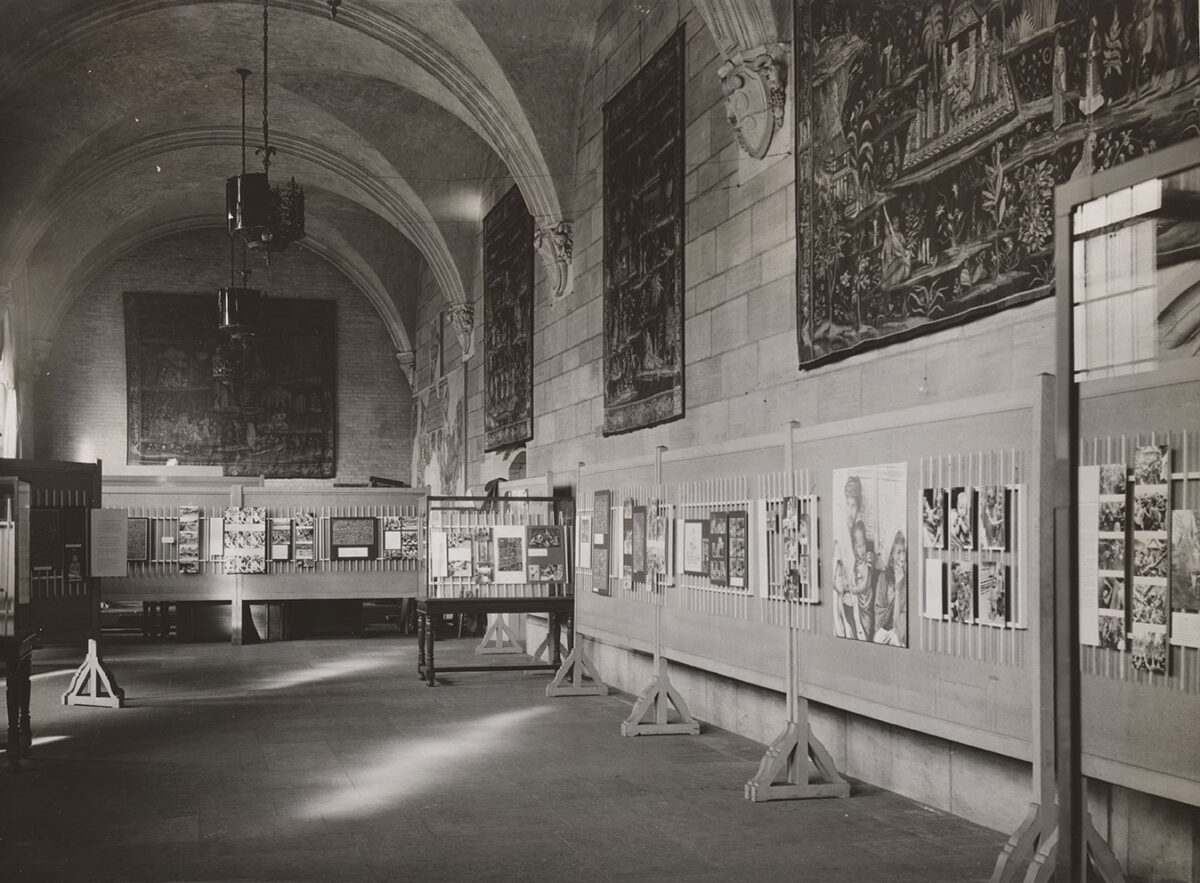

As an institution, MoMA was committed to these same ideas. In addition, some of the emigrant Bauhaus artists who had made their way to the United States after the closing of the Bauhaus by the Nazis in 1933 were committed to ideas of producing psychological agency through vision. Bauhaus artist Alexander Schawinsky was invited by the Museum (as opposed to Bateson personally) to design Bali, Background for War. Turner has noted that the museum was an important wartime node, one that mobilized Bauhaus methods. Victor D’Amico (founding director of MoMA’s Department of Education), for example, mobilized László Moholy-Nagy’s ideas for treating and resocializing veterans through the Museum’s War Veterans’ Art Center, which opened in 1944.8Turner, The Democratic Surround, 182–3. MoMA likewise employed Bauhaus artist and designer Herbert Bayer’s techniques for extending field of vision by hanging photographs below and above eye level to give viewers of wartime exhibitions a field of visual choices.9Bayer developed his concept of an “extended field of vision” in relation to László Moholy-Nagy’s concept of a “new vision” and its implicit ideas that human evolution is tied to vision and design. See Christian Hiller, “Vision in Motion —> Information Landscapes—From State Props and Camouflage Techniques to Democratic Apparatus and Cybernetic Networks,” in bauhaus imaginista Journal 4, March 11, 2019, https://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/4250/vision-in-motion-information-landscapes. Bayer designed MoMA exhibitions Road to Victory, which was curated by photographer Edward Steichen in 1942, and Airways to Peace: An Exhibition of Geography for the Future, which was planned and directed by Monroe Wheeler in 1943.10Road to Victory, The Museum of Modern Art, May 21–October 4, 1942; Airways to Peace: An Exhibition of Geography for the Future, The Museum of Modern Art, July 2, 1943–October 31, 1943.

Schawinsky attended the Bauhaus and studied with Moholy-Nagy, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Walter Gropius, and Oskar Schlemmer. At the invitation of Josef Albers, he taught from 1936 to 1938 at Black Mountain College, where he developed the “Spectodrama,” a multimedia stage design. In response to MoMA’s interest in Bauhaus ideas of how vision might inform subjectivity, on October 28, 1943, Monroe Wheeler, then director of Exhibitions at MoMA as well as the Museum’s first director of Publications, wrote to Schawinsky to solicit a proposal for an exhibition based on the artist’s notion of “perspective,” which Schawinsky explained in terms of the “changes in visual conceptions with the climax of today’s formation of new visual experience in the making.”11Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, MoMA Exhs 239.1, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

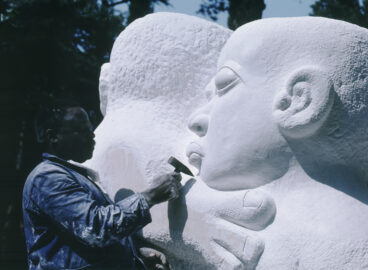

Bateson’s correspondence with Schawinsky in May 1943 indicates a highly collaborative exhibition-making process, wherein Bateson sent detailed notes, expanded the list of artwork to be included, and solicited feedback.12Box N27, folder 3, Postfield material, Balinese drawings exhibition, 1943, planning for exhibit, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. However, in July 1943, Bateson wrote to Wheeler and James Thrall Soby, then director of the Museum’s Armed Services Program, to request that Schawinsky be removed from the project. Bateson complained that Schawinsky lacked “respect for the material” and that he was “trimming . . . photographs to fit in with his scheme of rectangles regardless of the internal composition of the pictures.”13Box 4, folder 6, Gregory Bateson, Exhibit Bali, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Ultimately, Schawinsky was kept on, and in the press release for the exhibition, he is credited as designing the exhibition.14The Museum of Modern Art, “Museum of Modern Art Opens Exhibition of Bali, Background for War.” Despite their differences, Schawinsky’s Bauhaus training was evident in the exhibition. His design employed Bayer’s extended field of vision techniques—with images placed at different proximities to eye level—and performatively staged modern Balinese art against linear fields in a way that recalled the Spectodrama.15Silvy Chakkalakal, “Ethnographic Art Worlds: The Creative Figuration of Art and Anthropology,” Amerikastudien/American Studies 63, no. 4 (2018): 509.

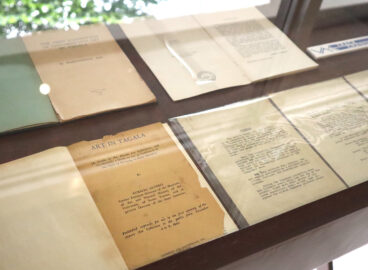

These affinities between Schawinsky’s Bauhaus ideas and Bateson’s interest in social engineering subjectivities through vision and aesthetic experience would take on an expanded and international vision through Bali, Background for War and Bateson’s work at MoMA. As part of his job at the Museum, Bateson attended a conference that, held in Chicago in March 1943 by the army’s Military Government Division, brought together faculty from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, and universities in Wisconsin and Michigan to develop training for the Army Specialized Training Program. Upon returning to New York, he and MoMA Film Library founding director, John Abbott, drafted a proposal to set up a Wartime Regional Materials Unit within MoMA that would be responsible for circulating artworks, cultural objects, graphic materials, photographs, and films to college campuses hosting the army program and eventually to nongovernmental agencies involved in postwar reconstruction. Bali, Background for War was an exhibition that attempted to put these ideas into operation. In his letter to Mortimer Graves, then executive director of the American Council of Learned Societies in Washington, DC, Bateson identifies the exhibition as a basis for setting up a Wartime Regional Materials Unit at MoMA.

Bateson’s papers include notes regarding who would be part of the unit and how it would be constituted through MoMA’s infrastructure. Bateson focused on the diversity of artistic and cultural material at the Museum, including graphic design and film, as well as on its public programs.16Box 8, folder 4, Wartime Regional Materials Unit, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. He considered the Museum an ideal institution to host the unit because it dealt “both with the Arts and with the Sciences.”17Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, GMH. I.3.E, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. The notes draw defined lines from Abbot, founding director of the Film Library, to Alfred Barr, founding director of the Museum, and Elodie Courter, who would organize circulating exhibitions, which were seen as fundamental to this unit. The unit was imagined to mobilize the different departments of the Museum, with dotted lines drawing different divisions across the institution into the unit. The inclusion of Barr in Bateson’s notes and Bateson’s supposed attempt at writing a Balinese modern art history point in turn to the transmutation of the currency of modern art history to military value. Bateson’s exhibition expanded the visions of modern art history that Barr had mapped out in his diagrams on the development of abstract art.18Glenn D. Lowry, “Abstraction in 1936: Barr’s Diagrams,” in Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 359–63. The anthropologist’s vision for MoMA was that the Museum would be an apparatus that produced intelligence derived from exhibitionary experience and the visual analysis of art. This intelligence during the war represented a convergence of the anthropological and the art historical as these were mobilized toward militaristic ends. Ultimately, however, Bateson’s proposal to develop a Wartime Regional Materials Unit within MoMA was not realized.19Materials for Circulation, Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, CE II.1.40.2, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

At first glance, Bali, Background for War was not a particularly successful venture. Yet, it can still be considered an important exhibition of its time and one that is significant in a Southeast Asian modern art history. At the close of the exhibition in 1943, Bateson joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), an American wartime intelligence agency. This was an unusual achievement given Bateson was a British national. Created in 1942, the OSS was the first centralized intelligence agency in the United States. It was the institutional predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).20Jennifer Davis Heaps, “Tracking Intelligence Information: The Office of Strategic Services,” American Archivist 61, no. 2 (Fall 1998): 287–308. David Price, an American anthropologist who has spent his career studying the historical and contemporary military uses of anthropology, has noted in his archival research on Bateson’s wartime work that the OSS was interested in the techniques of visual anthropology.21David H. Price, Anthropological Intelligence: The Deployment and Neglect of American Anthropology in the Second World War (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 318.

An OSS memo Bateson authored in November 1944 suggests strategies for maintaining the long-term interests of the United States in South Asia.22Gregory Bateson, “Office of Strategic Services South East Asia Command: Interoffice Memo from Gregory Bateson to Dillon Ripley, Subject: ‘Your Memo No. 53’ Dated 11/15/44 Released by Central Intelligence Agency under Freedom of Information Act request August 1994.” FOIA Reference F94-1511. The link to this document has since expired. David Price may have the only copy of this document. Therefore, the reading provided here is from his published source, namely, Price, “Gregory Bateson and the OSS,” Human Organization 57, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 379–84. Bateson’s position paper envisions the postwar period as an extension of the prewar colonial system. His memo posits a moderation of the dynamic of “exhibitionism” and “spectatorship” to manage possible rebellion from independence movements—concepts that Bateson had first deployed in explaining child-rearing norms in different cultures. In the memo, Bateson elaborates:

The most significant experiment which has yet been conducted in the adjustment of relations between “superior” and “inferior” peoples is the Russian handling of their Asiatic tribes in Siberia. The findings of this experiment support very strongly the conclusion that it is very important to foster spectatorship among the superiors and exhibitionism among the inferiors. In outline, what the Russians have done is to stimulate the native peoples to undertake a native revival while they themselves admire the resulting dance festivals and other exhibitions of native culture, literature, poetry, music and so on. And the same attitude of spectatorship is then naturally extended to native achievements in production or organization. In contrast to this, where the white man thinks of himself as a model and encourages the native people to watch him in order to find out how things should be done, we find that in the end nativistic cults spring up among the native people. The system gets overweighed until some compensatory machinery is developed and then the revival of native arts, literature, etc., becomes a weapon for use against the white man. . . . If, on the other hand, the dominant people themselves stimulate native revivalism, then the system as a whole is much more stable, and the nativism cannot be used against the dominant people.23Gregory Bateson, “Office of Strategic Services South East Asia Command,” quoted in Price, “Gregory Bateson and the OSS,” Human Organization 57, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 382. Emphasis mine.

Bateson suggests that if Indigenous peoples are encouraged to exhibit and celebrate their culture, as opposed to being encouraged to model themselves on Western culture, then “nativism cannot be used against the dominant people.”24Bateson, “Office of Strategic Services South East Asia Command.” Taken at face value, Bateson’s comments read as patronizing prescriptions for how to manage the postwar decolonizing process. Yet at the same time, an inverse relationship of cultural relations of “occupation” was being brought to the fore. In Bali, Background for War, Bali defined the region that the American soldier was to reoccupy. In this framework, the exhibition established an exhibitionism-spectatorship dynamic in which American soldiers were the spectators celebrating the culture of a region that they were liberating. In theory, American soldiers were placed in an exhibitionism-spectatorship dynamic that prepared them for the more benign reoccupation and postwar worldbuilding that they would have to enact in the Pacific.

Price detailed that when he declassified Bateson’s documents under the Freedom of Information Act in the 1990s, Bateson’s memo from November 1944 was found in the CIA archive and not the OSS archive. This suggests that Bateson’s advice for intelligence gathering was influential beyond World War II and perhaps formative to the CIA. Indeed, in 1951, only four short years after its founding, the CIA outlined a policy on Cold War weapons. The classified report considers culture a “Cold War Front” and advocates for private foundations to patronize and issue commissions to artists “who could create works of art symbolical of the struggle against tyranny in their native lands.”25Paul C. David, Office of Plans and Policy, to Everett Gleason, National Security Council; Charles Hayes[?], Department of Defense; Alan Dines, Central Intelligence Agency; and Melville Ruggles, Department of State, memo dated October 17, 1951, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80R01731R003500170002-8.pdf. The CIA would also infamously fund cultural organizations around the world, including the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Asia Foundation.26See David H. Price, Cold War Deceptions: The Asia Foundation and the CIA (Washington: University of Washington, 2024). Both organizations contributed to the advancement of modern art internationally in the postwar years. From 1951, the CIA put into effect a program code-named DTPillar to influence the development of nationbuilding in Asia as a means to limit the growth of communism. Stirred by a public exposé in Ramparts magazine (in circulation from 1962 to 1975), the CIA ceased funding of cultural organizations in 1967.27Price, Cold War Deceptions.

Bateson was also strategic in targeting individuals who should see Bali, Background for War. He wrote personal invitations to the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University and to individuals at the OSS.28A loose sheet from Bateson’s archive of papers that lists names related to the organizing of Bali, Background for War indicates the possible network of influence the exhibition and his work might have. This long list, which indicates the people Bateson intended to invite, includes the Office of Indian Affairs, the Fine Arts Commission, the Freer Gallery, the Far East Section of the Congressional Library, Congress and the House of Representative, diplomats from the British Embassy, the military, the OSS, and others. Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, Jane Belo, Ruth Benedict, Edith Cobb, Lenora Foerstel, Reo Fortune et al., box 4, folder 5, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Particularly telling is a loose list that includes Cora Du Bois (OSS, 1942–45). Du Bois was chief of research and analysis for the Southeast Asia Command by 1944 and, after World War II, influenced the framing of Southeast Asia through her positions as chief of the Southeast Asia Branch of the US State Department’s Office of Intelligence Research (from 1945 to 1949) and as an academic at Harvard University. The list also includes Charles Fahs (OSS, 1941–45), who became chief of the Research and Analysis Division (Far East) of the OSS in 1942 and director of the Humanities Division of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1950, where he was directly involved in allocating Rockefeller grants and providing critical support to individual artists and intellectuals as well as to museums and art spaces in Southeast Asia.29“Charles B. (Charles Burton) Fahs: Summary,” The Online Collection and Catalog of Rockefeller Archive Center,” https://dimes.rockarch.org/agents/8fgdhQozzVZpzKucKCQP9W. In 1947, as if telegraphing Bateson’s comment about regions as a sane orchestration of the world, Du Bois, having returned from her service in the OSS and been asked to speak about cultural anthropology and Southeast Asia, stated at Smith College: “Regions and areas, like fields of academic learning, are artificial boundaries which we erect around our curiosity. They do not represent limits of integrated reality, but defenses built to encompass the frailties of human comprehension.”30Cora Alice Du Bois, Social Forces in Southeast Asia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, [1949]), 27. This correlation and the constellated network of Bali, Background for War raises complex questions about US postwar and postimperial worldbuilding and intelligence, as well as about Southeast Asian modern art.

After the war, Bateson would advance his ideas on visual anthropology in other fields. In 1947, he addressed the United Nations, giving a speech titled “Atoms, Nations and Cultures” to argue for the urgency of social engineering based on the cultural analysis derived from visual anthropology.31See Gregory Bateson, “Atoms, Nations, and Cultures,” International House Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1947): 47–50.

Twenty-four years after Bali, Background for War opened, in 1967, Bateson published the essay “Style, Grace, and Information in Primitive Art.”32Gregory Bateson, “Style, Grace, and Information in Primitive Art,” in Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology (San Francisco, Chandler, 1972; repr., New Jersey: Northvale, 1987), 137–61. Citations refer to the Northvale edition. In this text, he performs an analysis of Balinese art as information coded in style, material, composition, and skill. He emphasizes the profundity of art in terms of its relational quality. Thus, he argues, Balinese paintings, under the influence of traditional and Western art forms, encapsulate the communication process between these societies. Furthermore, the text resonates with Bateson’s interest in addressing differences in international relations, which could also be read as laying out the framework for data to remake the world.33See Bateson, “Style, Grace, and Information” and “Comments on Part II” 154–6 and 162–4. In this sense, Bali, Background for War in many ways foreshadowed Bateson’s work on cybernetics in the 1960s and throughout the Cold War.34See Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind.

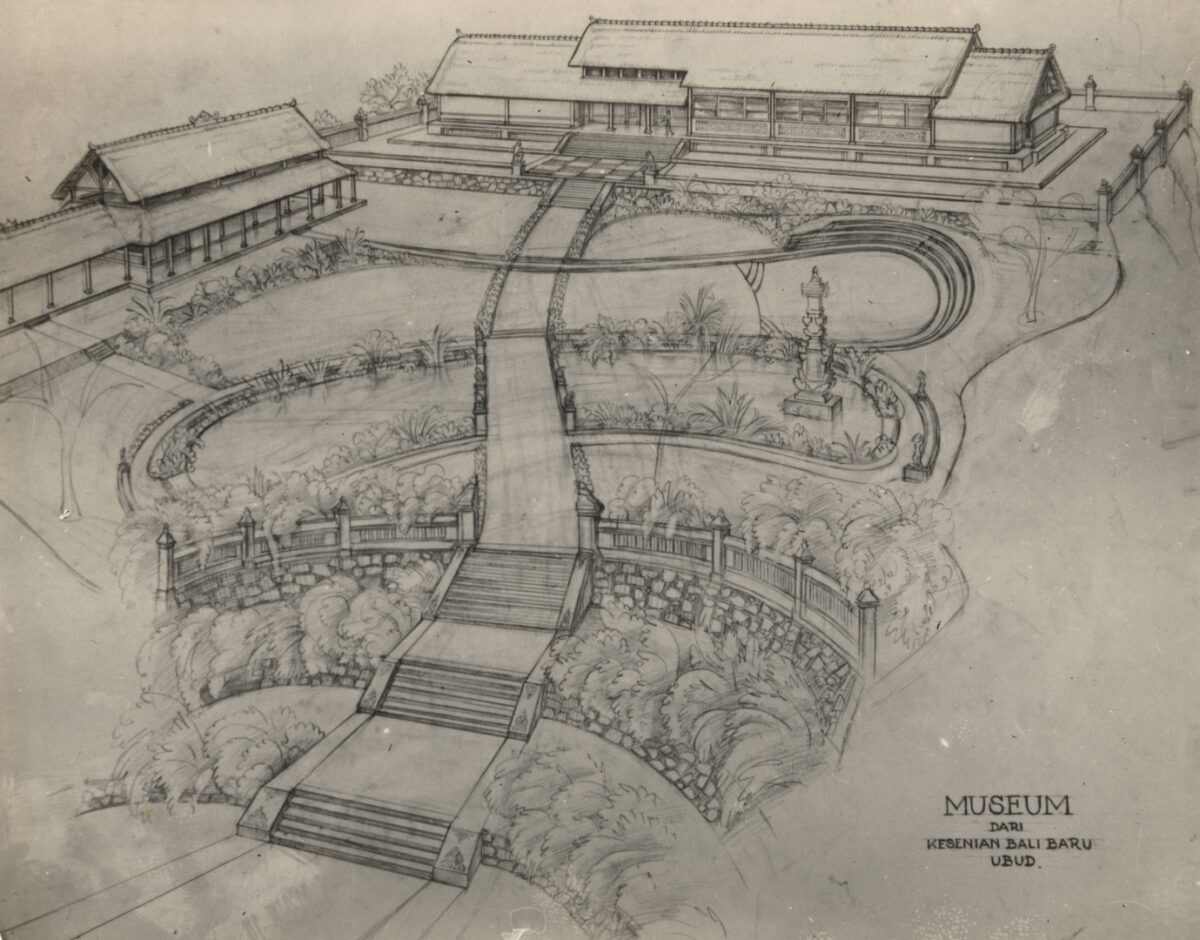

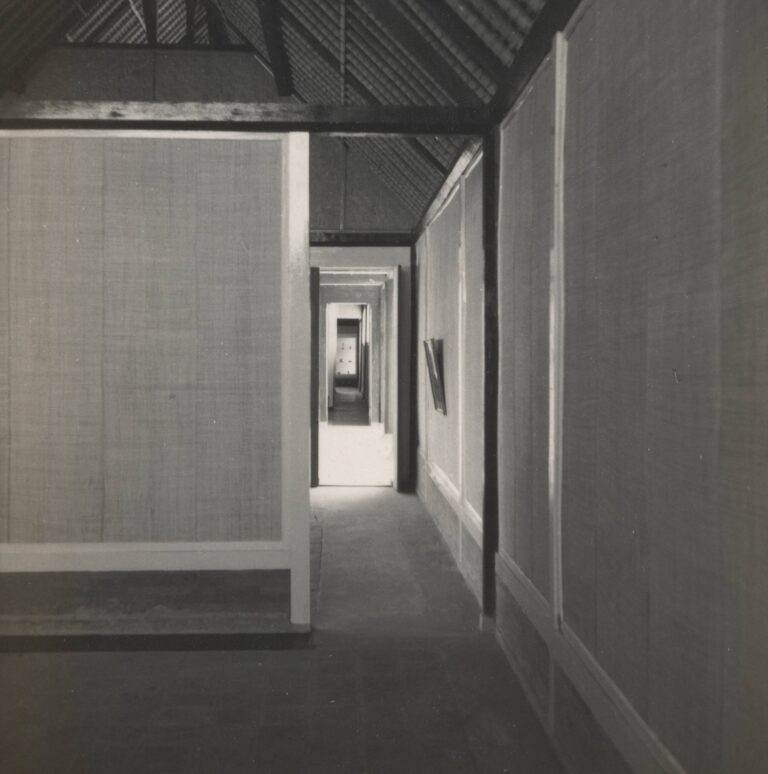

The cross-cultural relations based on aesthetic experiences with modern art that defined Bali, Background for War were echoed in MoMA’s contributions to the postwar construction of modern art in Bali. In 1953, the foundation Puri Lukisan was set up to establish a museum of modern Balinese art in Ubud. Tjokorda Gee Agung was its founding chairman while Rudolf Bonnet was its curator. The museum sought support from patrons of Balinese art in Holland, the United States, and England. Monroe Wheeler answered the call. Beyond sending a book on the care of artworks, he supported the development of the museum by soliciting donations from American foundations. The first organization he approached was the Asia Foundation, which would contribute to the building in 1956 of Museum Puri Lukisan, the oldest museum in Bali. Wheeler might not have known at the time that the Asia Foundation received funds from the CIA. Nevertheless, the networked triangulation of capital flows from the CIA as well as the belief in aesthetic experience being able to mold subjectivities is important in the intelligence-making project of modern art in the Cold War.35Wheeler might not have known at the time that the Asia Foundation received funds from the CIA. Nevertheless, the networked triangulation of capital flows from the CIA as well as the belief in aesthetic experience being able to mold subjectivities is important in the intelligence-making project of modern art in the Cold War. In his letter to the Asia Foundation, dated July 10, 1955, Wheeler notes that a financial contribution to the Indonesian government to complete the building of the museum would be an admirable “token of American concern with the fine arts, which is too little understood in Asia,” extending MoMA’s wartime concern for Balinese modern art and Southeast Asia into the postwar period.36Monroe Wheeler Papers, MW I.128, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

Bali, Background for War, when read against its possible influences on the cultural Cold War in the region and Bateson’s postwar accomplishments, anticipates exhibitions of Southeast Asian modern art as forms of intelligence-making, marrying the regional as a method in structuring the world with “modern art” and as a product of international exchange. Thus, Bali, Background for War offers a vista onto early cybernetic entanglements between Southeast Asia and modern art. It is important to keep in mind that MoMA did not set out to make a regional art exhibition with Bali, Background for War. Neither did the Museum set out to influence the policies of the cultural Cold War in Southeast Asia that Southeast Asian modern artists (like the Balinese modernists) would later navigate in seeking support for their own development through the Asia Foundation and other CIA-funded organizations. As an exhibition that predates Southeast Asia as a field of area studies, Bali, Background for War is an exhibitionary method: it is at once a field of relations, a feedback loop, and an open-ended imaginary produced from comparatively looking at modern art. Bali, Background for War foreshadowed future articulations of the relations that have come to define cybernetics as a field. As this essay argues, the exhibition also expands our understanding of MoMA’s influence as a museum and center for a global history of modern art, a critical part of the construction of a postwar world order.

*This essay has been adapted from and expands on an unpublished chapter from the author’s dissertation titled “Exhibiting Southeast Asia in the Cultural Cold War: Geopolitics of Regional Art Exhibitions (1940s–1980s),” Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2023.

**With special thanks to Ana Marie of the Archives, Library, and Research Collections Department and Ottilie Lighte from the Imaging and Visual Resources Department of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 1The Museum of Modern Art, “Museum of Modern Art Opens Exhibition of Bali, Background for War,” press release [1943], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/895/releases/MOMA_1943_0047_1943-08-10_43810-44.pdf.

- 2See “John Hay Whitney Announces Museum of Modern Art Will Serve as a Weapon of National Defense,” press release [1941], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/676/releases/MOMA_1941_0015_1941-02-28_41228-14.pdf; and Nathaniel Brennan, “The Cinema Intelligence Apparatus: Gregory Bateson, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, and the Intelligence Work of Film Studies during World War II,” chap. 8 in Cinema’s Military Industrial Complex, ed. Haidee Wasson and Lee Grieveson (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018).

- 3See Brennan, “The Cinema Intelligence Apparatus.”

- 4See Fred Turner, The Democratic Surround: Multimedia & American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

- 5In this respect, Turner notes in his conceptualization of the surrounds that Bateson and Mead’s work was motivated by addressing the needs of the Allied Forces. On the one hand, Allied soldiers needed information on the enemy and the allied national cultures they would encounter. On the other hand, because of the fighting, they could not send researchers to those places to perform the necessary studies. Thus, Mead and Bateson began to assemble cultural material from overseas and to study what they called “culture at a distance.” See Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942).

- 6Turner, The Democratic Surround, 74.

- 7See Turner, The Democratic Surround, 73. See Memorandum on a Proposed Exhibit on Democracy in the Museum of Modern Art, box 5, folder 1, Exhibits, Democracy, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 8Turner, The Democratic Surround, 182–3.

- 9Bayer developed his concept of an “extended field of vision” in relation to László Moholy-Nagy’s concept of a “new vision” and its implicit ideas that human evolution is tied to vision and design. See Christian Hiller, “Vision in Motion —> Information Landscapes—From State Props and Camouflage Techniques to Democratic Apparatus and Cybernetic Networks,” in bauhaus imaginista Journal 4, March 11, 2019, https://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/4250/vision-in-motion-information-landscapes.

- 10Road to Victory, The Museum of Modern Art, May 21–October 4, 1942; Airways to Peace: An Exhibition of Geography for the Future, The Museum of Modern Art, July 2, 1943–October 31, 1943.

- 11Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, MoMA Exhs 239.1, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 12Box N27, folder 3, Postfield material, Balinese drawings exhibition, 1943, planning for exhibit, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 13Box 4, folder 6, Gregory Bateson, Exhibit Bali, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 14The Museum of Modern Art, “Museum of Modern Art Opens Exhibition of Bali, Background for War.”

- 15Silvy Chakkalakal, “Ethnographic Art Worlds: The Creative Figuration of Art and Anthropology,” Amerikastudien/American Studies 63, no. 4 (2018): 509.

- 16Box 8, folder 4, Wartime Regional Materials Unit, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 17Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, GMH. I.3.E, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 18Glenn D. Lowry, “Abstraction in 1936: Barr’s Diagrams,” in Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 359–63.

- 19Materials for Circulation, Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, CE II.1.40.2, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 20Jennifer Davis Heaps, “Tracking Intelligence Information: The Office of Strategic Services,” American Archivist 61, no. 2 (Fall 1998): 287–308.

- 21David H. Price, Anthropological Intelligence: The Deployment and Neglect of American Anthropology in the Second World War (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), 318.

- 22Gregory Bateson, “Office of Strategic Services South East Asia Command: Interoffice Memo from Gregory Bateson to Dillon Ripley, Subject: ‘Your Memo No. 53’ Dated 11/15/44 Released by Central Intelligence Agency under Freedom of Information Act request August 1994.” FOIA Reference F94-1511. The link to this document has since expired. David Price may have the only copy of this document. Therefore, the reading provided here is from his published source, namely, Price, “Gregory Bateson and the OSS,” Human Organization 57, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 379–84.

- 23Gregory Bateson, “Office of Strategic Services South East Asia Command,” quoted in Price, “Gregory Bateson and the OSS,” Human Organization 57, no. 4 (Winter 1998): 382. Emphasis mine.

- 24Bateson, “Office of Strategic Services South East Asia Command.”

- 25Paul C. David, Office of Plans and Policy, to Everett Gleason, National Security Council; Charles Hayes[?], Department of Defense; Alan Dines, Central Intelligence Agency; and Melville Ruggles, Department of State, memo dated October 17, 1951, https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80R01731R003500170002-8.pdf.

- 26See David H. Price, Cold War Deceptions: The Asia Foundation and the CIA (Washington: University of Washington, 2024).

- 27Price, Cold War Deceptions.

- 28A loose sheet from Bateson’s archive of papers that lists names related to the organizing of Bali, Background for War indicates the possible network of influence the exhibition and his work might have. This long list, which indicates the people Bateson intended to invite, includes the Office of Indian Affairs, the Fine Arts Commission, the Freer Gallery, the Far East Section of the Congressional Library, Congress and the House of Representative, diplomats from the British Embassy, the military, the OSS, and others. Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, Jane Belo, Ruth Benedict, Edith Cobb, Lenora Foerstel, Reo Fortune et al., box 4, folder 5, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 29“Charles B. (Charles Burton) Fahs: Summary,” The Online Collection and Catalog of Rockefeller Archive Center,” https://dimes.rockarch.org/agents/8fgdhQozzVZpzKucKCQP9W.

- 30Cora Alice Du Bois, Social Forces in Southeast Asia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, [1949]), 27.

- 31See Gregory Bateson, “Atoms, Nations, and Cultures,” International House Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1947): 47–50.

- 32Gregory Bateson, “Style, Grace, and Information in Primitive Art,” in Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology (San Francisco, Chandler, 1972; repr., New Jersey: Northvale, 1987), 137–61. Citations refer to the Northvale edition.

- 33See Bateson, “Style, Grace, and Information” and “Comments on Part II” 154–6 and 162–4.

- 34See Bateson, Steps to an Ecology of Mind.

- 35Wheeler might not have known at the time that the Asia Foundation received funds from the CIA. Nevertheless, the networked triangulation of capital flows from the CIA as well as the belief in aesthetic experience being able to mold subjectivities is important in the intelligence-making project of modern art in the Cold War.

- 36Monroe Wheeler Papers, MW I.128, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.