This two-part essay introduces Bali, Background for War: The Human Problem of Reoccupation, an exhibition curated by anthropologist and cybernetics pioneer Gregory Bateson at The Museum of Modern Art in 1943. It is an important exhibition in Southeast Asian modern art history and occupies an exceptional place in the Museum’s institutional history. In this first text, researcher and curator Kathleen Ditzig proposes Bali, Background for War as an exceptional case of how the exhibition-form operates as a confluence of anthropological and military intelligence, wherein modern art is mobilized to promote cultural sensemaking and worldmaking. She explores how this exhibitionary framework underpinned the constitution of subjectivities for a peaceful world order that the cultural policies of the United States in the Cold War would build upon.

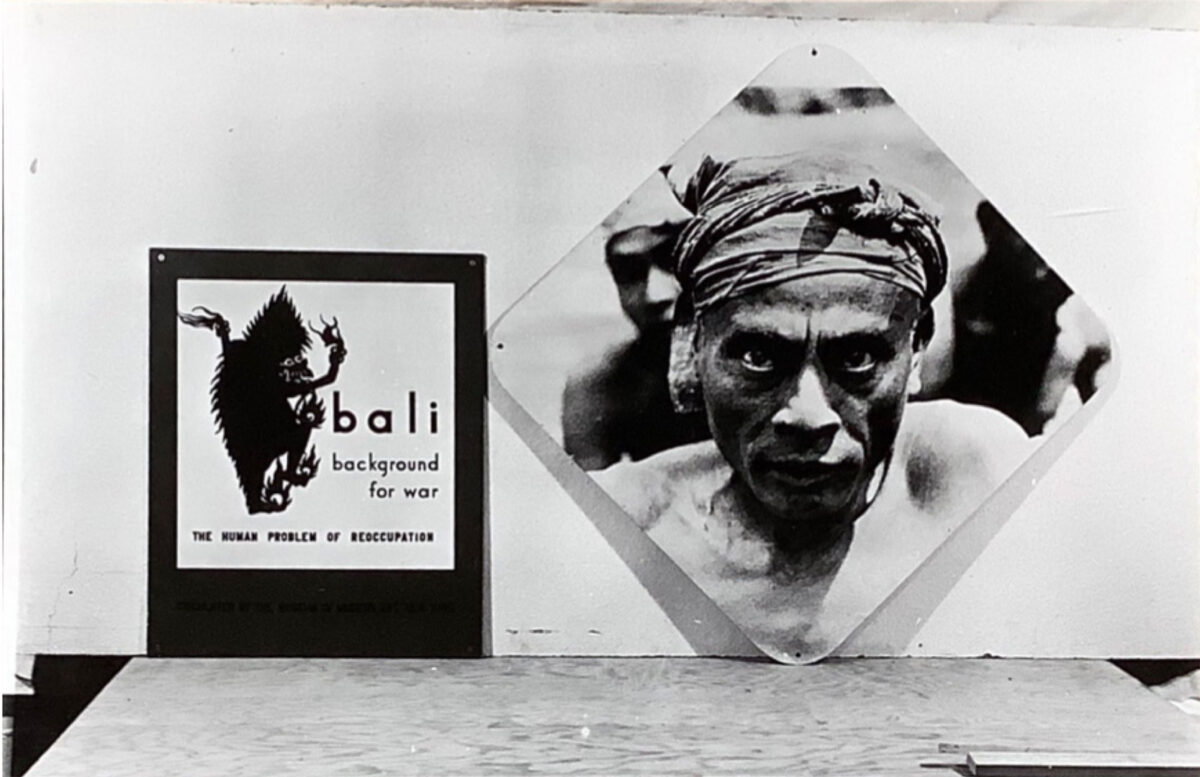

The whites of eyes and the glint of teeth, the only discernible features in the otherwise dark shape of the Balinese shadow puppet of the witch Rangda in her supernatural form, were probably the first things visitors encountered when they entered the 1943 exhibition Bali, Background for War: The Human Problem of Reoccupation. With its fiery head and tendril fingers, the shadow puppet is a totem for a ferocious “other.” Encapsulating the anxieties that contextualized this exhibition, which coincided with World War II, the shadow puppet embodied the sensibility of the exhibition-form—an elusive sensemaking of a culture oceans away.

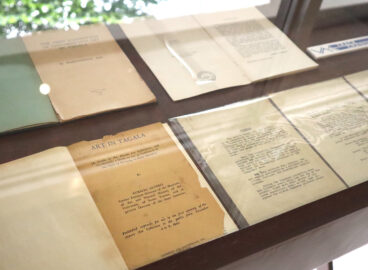

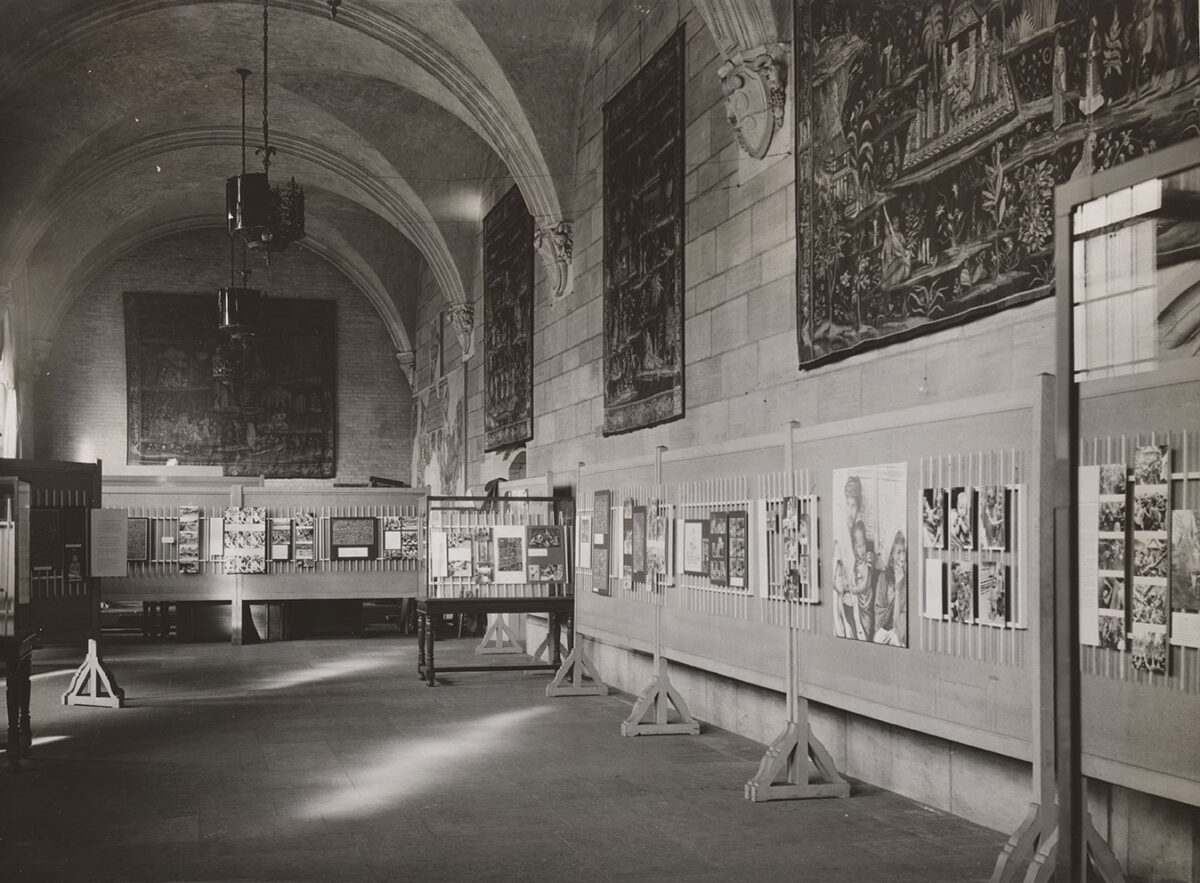

A wartime exhibition curated by anthropologist and cybernetics pioneer Gregory Bateson, Bali, Background for War opened at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in late summer 1943 and then traveled to universities and museums across North America.1The exhibition opened at MoMA on August 11, 1943, and ran through September 19, 1943. It traveled to the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (October 13–31, 1943), where it was titled Bali: The Human Problem of Reoccupation; the Yale University School of the Fine Arts in New Haven, CT (November 12–December 5, 1943); the Art Institute of Chicago (December 1943–January 1944); the Detroit Institute of Arts (February 1944–March 1944); the University of Minnesota (March–April 1944); the Pella Historical Society in Iowa (May 1944); the Taylor Museum in Colorado Springs (June to July 1944); the San Francisco Museum of Art (July to August 1944); Beloit College in Wisconsin (November–December 1944); the Person Hall Art Gallery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (January 1945); and the University of Florida (February–March 2, 1945. “THE PEOPLE OF BALI (BACKGROUND FOR WAR): COMMENTS about the exhibition,” undated manuscript, The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, 239, CE.MF.13:0433, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Unlike MoMA’s other wartime exhibitions of the early 1940s, such as Road to Victory (1942) and Airways to Peace (1943), Bali, Background for War did not visually represent the efforts of the Allied Forces. Instead, it presented Balinese sculpture, paintings, puppets, and idols—Balinese modern art—collected by Bateson and Margaret Mead, his wife and collaborator at the time, as well as a selection of photographs from the more than 25,000 images taken during their joint anthropological expedition to Bali in 1936–39.2The Museum of Modern Art, “Museum of Modern Art Opens Exhibition of Bali, Background for War,” press release, [1943], www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/895/releases/MOMA_1943_0047_1943-08-10_43810-44.pdf.

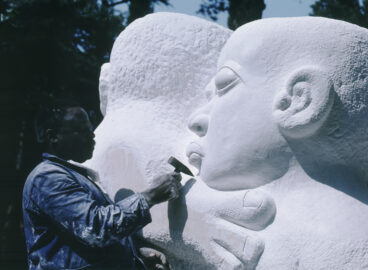

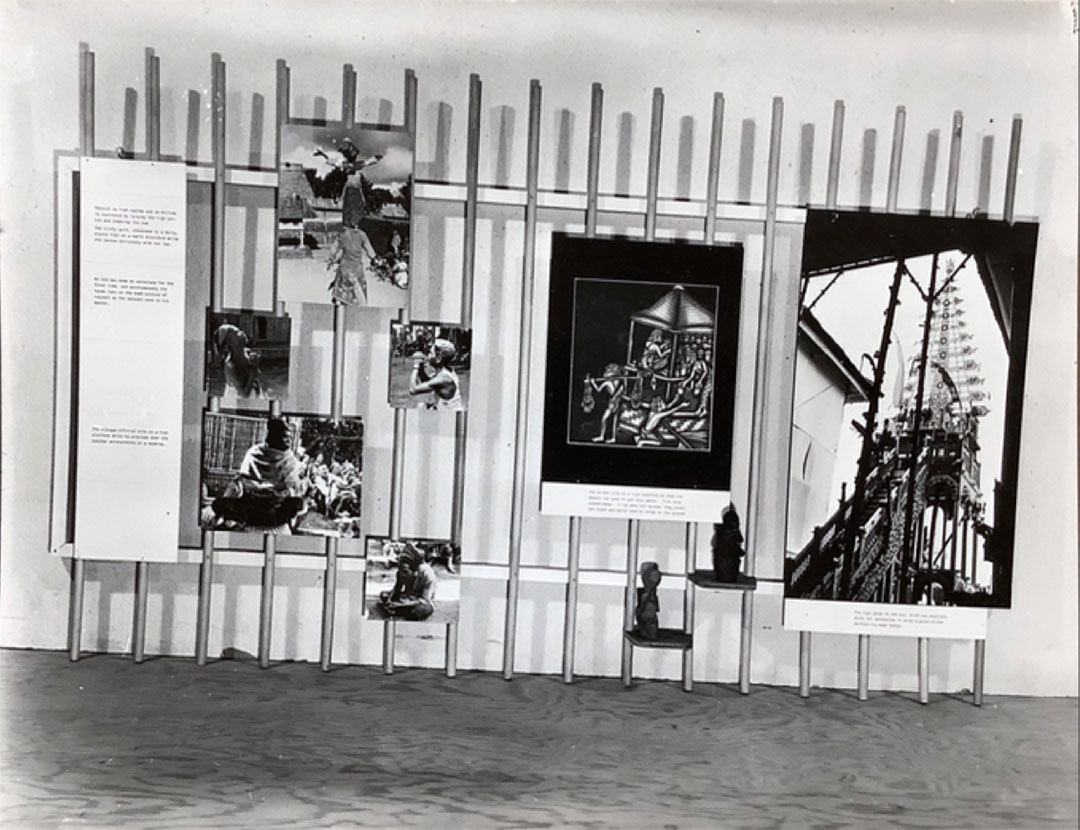

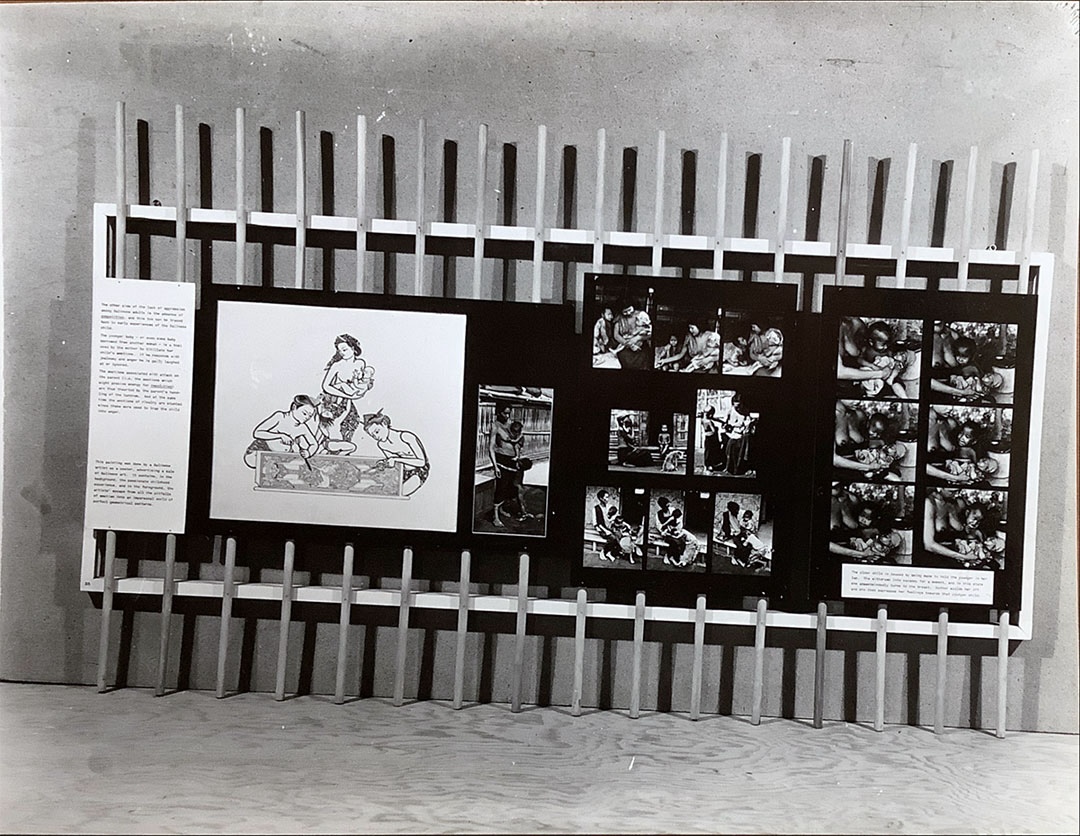

Designed by Bauhaus artist and designer Xanti Schawinsky to be portable, the exhibition’s display system relied on wooden structures composed of thin vertical poles on which artworks and cultural objects were hung or otherwise installed in a variety of ways and at different heights. Balinese cultural objects were installed to facilitate distinct sight lines, which Bateson referred to as “vistas,”3In an exchange with filmmaker Maya Deren in 1946, Bateson described an exhibition as a system of vistas. In speaking about exhibition design, he commented, “The possible ways in which themes may be related to each other will also include all those cases which could be diagrammed by personifying the themes and then saying that the relationship between the themes is comparable to a human relationship.” “An Exchange of Letters between Maya Deren and Gregory Bateson,” October 14 (Autumn 1980): 19. with the individual pieces appearing to float relative to one another. The exhibition presented works and objects on the same ground, alluding to how the artist and their making of the artwork were the material products of a society in which they lived and worked.

Bali, Background for War was an anthropological exhibition of Balinese modern art and culture conceived as a technology for producing a necessary subjectivity in the American infantry and civilian administrators who would oversee the “reoccupation” of Japanese-captured territories, such as Bali. The exhibition sought to cultivate the ability to recognize cultural patterns so as to foster understanding of “those habits of thought and behavior” characteristic of a particular people.4The Museum of Modern Art, “Bali, Background for War Heads List of New Exhibitions to be Shown at Museum of Modern Art,” press release, [1943], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_325408.pdf?_ga=2.209621588.737891115.1680105186-1269841651.1670570115. In turn, it represented a weaponization of the then emerging methods of visual anthropology. Bali, Background for War was, in this respect, an exceptional exhibition. Bateson’s only curatorial effort while he was employed at MoMA (from 1942 to 1943), it encapsulated aspects of Bateson and Mead’s most influential work in visual anthropology—at the time, a new subfield of anthropology that would, in part, lead to a break from the racial codification informing exhibitions of Balinese culture in Western museums in the 1930s, wherein biological markers identified race as a defining paradigm of a people’s identity.5Urmila Mohan, Fabricating Power with Balinese Textiles (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2018), 97. Mead and Bateson’s use of film and photography in their fieldwork in Bali has been interpreted by scholars such as Urmila Mohan as a move away from such racialized logic.6See Mohan, Fabricating Power.See also Silvy Chakkalakal, “Ethnographic Art Worlds: The Creative Figuration of Art and Anthropology,” Amerikastudien/American Studies 63, no. 4 (2018): 489–515.

After their fieldwork in Bali, Mead and Bateson developed this inquiry into a method that became a “leading social-scientific strategy in World War II” through what Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan has described as “a new alliance of federal and foundation sponsorship with university and industrial partners.”7Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan, Code: From Information Theory to French Theory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 2023), 66. This included the Committee for National Morale, which the couple joined in 1939, and the Council on Intercultural Relations, which they co-established in 1942 to coordinate research projects among an interdisciplinary group of anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists interested in analyzing contemporary cultures to benefit the war effort.8Growing from this work, the turn of phrase “the study of culture at a distance” is most associated with Mead and Ruth Benedict. From 1947 to 1952, Mead worked on a project with funding from the United States Navy to study contemporary cultures. This project, conducted at Columbia University, culminated in the anthology The Study of Culture at a Distance (1953). Essentially, the study of culture when fieldwork is not possible would be based on patterns observed in material culture.

Mead and Bateson cowrote Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (1942) based on their findings from their fieldwork in Bali. In this book, they lay out their new methodology of visual anthropology.9Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis ([New York]: [New York Academy of Sciences], 1942). See alsoIra Jacknis, “Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in Bali: Their Use of Photography and Film,” Cultural Anthropology 3, no. 2 (May 1988): 160–77. Photographs capture “behaviors” that are seen as logics or patterns that were registered across a society and found in individual actions or objects. The book explores the social relations that form the basis of larger social patterns. However, this study of Bali by visually surveying the cultural other has been critiqued by scholars such as Geoghegan as indebted to a Dutch colonial policy of turning Bali into a “living museum,” that is, of looking upon it as an idyllic “primitive” society—the assumption being that Balinese culture remained unchanged and thus could be essentialized and understood through visual codes. To be sure, Mead and Bateson’s lack of analysis of the Dutch administration renders their documentation and analysis problematic.10Geoghegan, Code, 67.

Bali, Background for War (1943) was, in essence, the physical manifestation of the method of visual anthropology fleshed out in Balinese Character. Indeed, the exhibition itself became a space in which anthropological methods produced a sense of knowing and relating through the visual encounter with art and cultural artifacts; yet, at the same time, it did not end up being solely an ethnographic representation. In one of Bateson’s many drafts of a press release, he explained that the exhibition would promote “[a] greater realistic understanding of the differences between peoples, of the ways in which each people has developed its own customs and its view of life” and that “if different people are to work together . . . and appreciate each other, some of these special peculiarities must be recognized” and “labelled and pointed out partly so that we may avoid stepping on each other’s toes but also so that each people may have opportunity to make its own special contribution to an organized world.”11Gregory Bateson to Miss Courier, “People of Bali,” box 4, folder 5, Gregory Bateson, Exhibitions, Bali in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, [n.d.], MSS32441. These ideas formed the groundwork for an exhibitionary logic in which the artwork is understood as indexical of a culture and people. Furthermore, it anticipates the belief in postwar art exhibitions as visual arguments for cultural affinities and thus the basis of a shared identity and political consciousness.

Bali, Background for War was the first “regional” exhibition of art from Southeast Asia. In 1943, the imagination of Southeast Asia as a region was a product of World War II. An offshoot of the India Command and formed in response to the Japanese conquest of the region, the South East Asia Command was created by the Allied Forces in August 1943, the same month that Bali, Background for War opened at MoMA.12Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere included Japan (and the territories of Korea, Taiwan, and Sakhalin), China, Manchukuo, French Indochina, the Dutch East Indies, Burma, Thailand, Malaya, and Siam. The concept of “Asia for Asiatics,” which had developed earlier in Japan, cultivated pan-Asian notions of an Asian community across Southeast Asia and South Asia through the propaganda efforts of the Japanese military during World War II. This argument was made with different outcomes across the region based on race and common interest. See Peter Duus, “The Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere: Dream and Reality,” Journal of Northeast Asian History 5, no. 1 (June 2008): 146–7. Southeast Asia is referenced in MoMA’s exhibition press release as the “conquered countries” of the Japanese.13The Museum of Modern Art, “Bali, Background for War Heads List of New Exhibitions to be Shown at Museum of Modern Art.” The Japanese occupation during World War II had been articulated as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, an economic, military, and cultural bloc of occupied countries in East and Southeast Asia that supported the Japanese war effort. In wartime propaganda, the Co-Prosperity Sphere was framed as part of a larger historic aim of resisting Western colonization and manipulation. Seeding a regional identity through a cultural program that included the establishment of “modern” arts education, it championed the revitalization of local, traditional, and Asian aesthetics across the region.14Masahiro Ushiroshoji, “An Introduction: The Seed Will Grow into a Great Garuda and Mighty Bings that Bear You Heavenward,” in The Birth of Modern Art in Southeast Asia: Artists and Movements, exh. cat. (Fukuoka: Fukuoka Art Museum, 1997), 218–9.

As a regional exhibition, Bali, Background for War was less a geographic understanding of the region as a proof of concept of Bateson’s theorization of a world order based on regions of cultures. While he does not explicitly point to it, Bateson’s presentation of modern artworks alongside anthropological materials advanced an aesthetic argument about the role of art in navigating cultural differences. It reflected an understanding of the region that was sensitive to the effects of war, one that offered an alternative visual logic to “Asian” aesthetics advanced by Japanese wartime propaganda.

Bateson’s notes about the exhibition indicate “Southeast Asia” alongside other themes such as “Problems of Overseas Administration,” “Problems of National Character,” “Intercultural Relations and Propaganda,” and “Problems of Visual Presentation.”15Box 4, folder 5, Gregory Bateson, Exhibitions, Bali in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441. His conceptualization of the region was a framework for organizing and ordering the world—one based on visual identification of “cultural patterns.” In memos regarding the exhibition, he commented that “in the organization and orchestration of the postwar world [,] many different types of technical insight will be required—political, geographic, economic and cultural.”16Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, GMH. I.3.E, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Furthermore, he highlighted that a key failure of the Treaty of Versailles was the lack of regional knowledge and warned that in the postwar epoch, there was a real risk that the cultural aspects of the various regions would “be ignored or imperfectly understood.”17Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, GMH. I.3.E, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Bateson believed that this would lead to conflict. In a letter to Mortimer Graves of the American Council of Learned Societies in Washington, DC, sent in April 1943, four months before the opening of Bali, Background for War, Bateson explained that he and Mead were “trying to arrange in the museum an exhibition of Balinese material (native paintings, carvings, observational films, and observational photographs of native behavior) as an example of what a single culture would look like when worked out in this way.”18Gregory Bateson to Mortimer Graves, The American Council of Learned Societies, [April 10,1943], box 8, folder 4, Gregory Bateson Wartime Regional Material Unit in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441.Gregory Bateson to Mortimer Graves, The American Council of Learned Societies, [April 10,1943], box 8, folder 4, Gregory Bateson Wartime Regional Material Unit in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441. He concluded by claiming the exhibition was part of a larger framework that was “the next logical step towards a sane orchestration of the world’s regional culture.”19Bateson to Graves, The American Council of Learned Societies, [April 10,1943]. If regions were a framework for organizing the world and integral to international relations and building a peaceful world, then the ability to read the cultural patterns found in art and its relationship to a society was crucial.

Bali, Background for War sought to represent “the patterns of thought and behavior” of the Balinese people through “works of art and [Bateson’s] photographs of daily life on the island.”20Wall text, Bali, Background for War, box OV 7–OV 8, container K53, Mead Oversized Bali Exhibition Display in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441. Developed with MoMA in mind, the exhibition set out a methodology of viewing that made the exhibition-form a generative site for producing “intelligence.” Intelligence in this regard took multiple forms, including the conversion of anthropological information on Balinese culture into “military intelligence,” wherein the viewer learning to read Balinese culture through the exhibition develops a skill necessary for the successful American “reoccupation” of Bali. The exhibition was firstly a collection of material and anthropological information that in the context of World War II had military value. Secondly, it was mobilized to cultivate skills and subjectivities for military application. In turn, the exhibition as a historical object points to an emergent “cultural” military industrial complex centered on modern art and anthropology.

In this context, the “regional” exhibition was a technology that converted anthropological intelligence into military intelligence, both in terms of apprehending a cultural other but also as a way of organizing the world through cultural regions. How was modern art integral to this convergence? How was the production of a modern subjectivity and exhibitionary logic of Southeast Asia entangled with the writing of modern art at MoMA, and how was it distinct from the colonial aesthetics of the census that scholars have pointed out in discussing Balinese Character?21See Fatimah Tobing Rony, “The Photogenic Cannot Be Tamed: Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson’s ‘Trance and Dance in Bali’,” in “Scenes Elsewhere,” special issue, Discourse 28, no.1 (Winter 2006): 5–27.

The artworks that Bateson and Mead presented in Bali, Background for War were procured from three main painting centers in Bali: Ubud, where most foreign artists in Bali had settled from the 1920s onward; Sanur, where some foreign artists lived and most vacationed; and Batuan, which tourists rarely visited. Bateson and Mead seemed to have been most interested in Batuan, where most of the paintings in Bali, Background for War were sourced from.22Bateson and Mead collected 1,288 paintings, 845 of which came from Batuan. There are 71 different painters, including children and apprentices, represented in this collection; however, only 22 of them can be considered serious painters who were part of an artistic community that painted and developed work together. Mead and Bateson were not just interested in the artworks as objects; they kept copious notes on the paintings they bought, noting when, where, and from whom they were purchased, and at times, they even collected comments from the artists about the works. While they did not write about these works explicitly, they did conduct a study of 23 painters. They developed a questionnaire on artistic training and the artists’ lives that their Indonesian assistant I Made Kaler administered to the 23 painters. See Hildred Geertz, Images of Power: Balinese Paintings Made for Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, exh. cat. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994), 5. By the time Mead and Bateson were in Bali, there was a thriving business of Balinese artists making tourist paintings for a Western audience. As products of transnational exchange, these works of art were quintessentially modern.

Hildred Geertz, in her study of Bateson and Mead’s collection of Balinese paintings and, more generally, of Batuan paintings, describes the paintings produced in Batuan as “bicultural” and “bound up in the meaning systems and aesthetic ideas of several cultures at once.”23Geertz, Images of Power, 3. She notes that only a few of the Batuan painters were directly taught by German artist Walter Spies and Dutch artist Rudolf Bonnet, both of whom lived in Ubud. For the most part, Batuan or Balinese painters at the time encountered Western images in textbooks, in foreign magazines, and in the form of small commercial images distributed within the Dutch colony.

Prior to Bateson and Mead’s arrival in Bali, there were already precedents of exchange and modernism on the island. The year 1928 is marked as the first time Western observers recorded art in Bali as consisting of new forms of representation. These observers went on to cultivate a tourist economy for such images.24Adrian Vickers, “Balinese Modernism,” in Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, ed. Low Sze Wee and Patrick D. Flores (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2018), 121. The Pita Maha, an artist society committed to modern art in Bali, was established in 1936 and active until 1940. It became associated with modern art of Bali, with Bonnet, a member of the society, organizing exhibitions of Balinese modernists in Indonesia and in Europe, including exhibitions in 1937 and 1938 in Amsterdam and London25.Vickers, “Balinese Modernism,” 125–6.

The modern style that emerged from this period in the 1930s and which defined the artworks that Bateson presented in Bali, Background for War was thus informed by engagement with Western art. As Adrian Vickers has noted, Balinese modern art in the 1930s was seen as exotically primitive and distinctly different from Western modernism. And yet, art dealers such as Dutch gallerist Carel van Lier sold Balinese modern art in Europe alongside European modern art.26Vickers, “Balinese Modernism,” 125–6.

Walter Spies housed Bateson and Mead upon their arrival in Bali in 1936 and provided their first introduction to Balinese paintings, influencing Bateson’s perspective on Balinese modern art.27See Margaret Mead, Letters from the Field, 1925–1975 (New York: Harper & Row, 1977). For MoMA’s installation of the exhibition, Bateson considered an additional section devoted to Balinese modern art.28I make this claim tentatively because the exhibition at MoMA was supposedly not photographed. We cannot be certain if this was eventually staged. See box 27, folder 3, Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. In the anthropologist’s personal papers, there is a memo to Xanti Schawinsky about the wall text alongside instructions regarding which photographs and artworks were to be installed. In addition, Bateson scribbled down several possible configurations for the works. A section called “History of Modern Balinese Art,” for example, was to be arranged in a straight row, suggesting a linear historical narrative. The selection of works would include one or two paintings by Spies and about ten artworks from Bateson and Mead’s collection. The wall text focused on the genealogy of the making of the artwork and described how artists made their works as part of a loose art history of modern Balinese art development, information that was then interspersed with short stories and mythical accounts such as how Spies gave paper and black ink to Balinese artist Sorbet and a whole school was born. The genealogy privileged Spies and his position in Balinese modern art at the expense of other influences, implicitly reflecting Bateson’s own perspective of Balinese art.

Bateson claims in the written guide that accompanied the traveling exhibition that all the artworks were of the artists’ “spontaneous invention,” with the exception of a painting by Ida Bagus Made Togog, who was asked to make pictures of his dreams.29The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, 239. CE.MF.15.0486, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. In this regard, Bateson’s mobilization of artworks might seem to speak to how Balinese artists authentically represented their inner lives and society. This was not necessarily the case, however. In her study of Bateson and Mead’s collection, Geertz found that the two anthropologists deeply influenced the Balinese artists. Throughout their fieldwork, the couple was in contact with Balinese painters who would not only travel to see them but also made art specifically to sell to them.30Geertz, Images of Power, 121.

While Bateson intended the artworks to be seen as sources of information about the inner lives of the peoples they represented, their makers were aware of the Western anthropological gaze of Bateson and Mead, which informed their process and, in particular, their subject matter. Thus, the Balinese society that Bali, Background for War pictured was one already in dialogue with an international world order and a modern art history.In this sense, Balinese modern art in the exhibition was relational, not just representative of a faraway culture. The photographed Balinese man and more generally the people whose gaze met those visiting the exhibition was thus returning a gaze that was part of a cultural exchange that spanned back to the 1930s and was a critical part of the definition of Balinese modern art. The regional imagination captured in Bali, Background for War was, in turn, an emergent international order framed by an encounter with modern art. This nexus of the anthropological and militaristic sensemaking that took shape as an exhibitionary technology of worldmaking during the Cold War will be unpacked in the second part of this essay.

With special thanks to Ana Marie of the Archives, Library, and Research Collections Department and Ottilie Lighte from the Imaging and Visual Resources Department of The Museum of Modern Art.

- 1The exhibition opened at MoMA on August 11, 1943, and ran through September 19, 1943. It traveled to the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (October 13–31, 1943), where it was titled Bali: The Human Problem of Reoccupation; the Yale University School of the Fine Arts in New Haven, CT (November 12–December 5, 1943); the Art Institute of Chicago (December 1943–January 1944); the Detroit Institute of Arts (February 1944–March 1944); the University of Minnesota (March–April 1944); the Pella Historical Society in Iowa (May 1944); the Taylor Museum in Colorado Springs (June to July 1944); the San Francisco Museum of Art (July to August 1944); Beloit College in Wisconsin (November–December 1944); the Person Hall Art Gallery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (January 1945); and the University of Florida (February–March 2, 1945. “THE PEOPLE OF BALI (BACKGROUND FOR WAR): COMMENTS about the exhibition,” undated manuscript, The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, 239, CE.MF.13:0433, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 2The Museum of Modern Art, “Museum of Modern Art Opens Exhibition of Bali, Background for War,” press release, [1943], www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/895/releases/MOMA_1943_0047_1943-08-10_43810-44.pdf.

- 3In an exchange with filmmaker Maya Deren in 1946, Bateson described an exhibition as a system of vistas. In speaking about exhibition design, he commented, “The possible ways in which themes may be related to each other will also include all those cases which could be diagrammed by personifying the themes and then saying that the relationship between the themes is comparable to a human relationship.” “An Exchange of Letters between Maya Deren and Gregory Bateson,” October 14 (Autumn 1980): 19.

- 4The Museum of Modern Art, “Bali, Background for War Heads List of New Exhibitions to be Shown at Museum of Modern Art,” press release, [1943], The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_325408.pdf?_ga=2.209621588.737891115.1680105186-1269841651.1670570115.

- 5Urmila Mohan, Fabricating Power with Balinese Textiles (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2018), 97.

- 6See Mohan, Fabricating Power.See also Silvy Chakkalakal, “Ethnographic Art Worlds: The Creative Figuration of Art and Anthropology,” Amerikastudien/American Studies 63, no. 4 (2018): 489–515.

- 7Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan, Code: From Information Theory to French Theory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press: 2023), 66.

- 8Growing from this work, the turn of phrase “the study of culture at a distance” is most associated with Mead and Ruth Benedict. From 1947 to 1952, Mead worked on a project with funding from the United States Navy to study contemporary cultures. This project, conducted at Columbia University, culminated in the anthology The Study of Culture at a Distance (1953). Essentially, the study of culture when fieldwork is not possible would be based on patterns observed in material culture.

- 9Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis ([New York]: [New York Academy of Sciences], 1942). See alsoIra Jacknis, “Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in Bali: Their Use of Photography and Film,” Cultural Anthropology 3, no. 2 (May 1988): 160–77.

- 10Geoghegan, Code, 67.

- 11Gregory Bateson to Miss Courier, “People of Bali,” box 4, folder 5, Gregory Bateson, Exhibitions, Bali in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, [n.d.], MSS32441.

- 12Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere included Japan (and the territories of Korea, Taiwan, and Sakhalin), China, Manchukuo, French Indochina, the Dutch East Indies, Burma, Thailand, Malaya, and Siam. The concept of “Asia for Asiatics,” which had developed earlier in Japan, cultivated pan-Asian notions of an Asian community across Southeast Asia and South Asia through the propaganda efforts of the Japanese military during World War II. This argument was made with different outcomes across the region based on race and common interest. See Peter Duus, “The Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere: Dream and Reality,” Journal of Northeast Asian History 5, no. 1 (June 2008): 146–7.

- 13The Museum of Modern Art, “Bali, Background for War Heads List of New Exhibitions to be Shown at Museum of Modern Art.”

- 14Masahiro Ushiroshoji, “An Introduction: The Seed Will Grow into a Great Garuda and Mighty Bings that Bear You Heavenward,” in The Birth of Modern Art in Southeast Asia: Artists and Movements, exh. cat. (Fukuoka: Fukuoka Art Museum, 1997), 218–9.

- 15Box 4, folder 5, Gregory Bateson, Exhibitions, Bali in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441.

- 16Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, GMH. I.3.E, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 17Department of Circulating Exhibitions Records, GMH. I.3.E, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 18Gregory Bateson to Mortimer Graves, The American Council of Learned Societies, [April 10,1943], box 8, folder 4, Gregory Bateson Wartime Regional Material Unit in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441.Gregory Bateson to Mortimer Graves, The American Council of Learned Societies, [April 10,1943], box 8, folder 4, Gregory Bateson Wartime Regional Material Unit in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441.

- 19Bateson to Graves, The American Council of Learned Societies, [April 10,1943].

- 20Wall text, Bali, Background for War, box OV 7–OV 8, container K53, Mead Oversized Bali Exhibition Display in Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, MSS32441.

- 21See Fatimah Tobing Rony, “The Photogenic Cannot Be Tamed: Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson’s ‘Trance and Dance in Bali’,” in “Scenes Elsewhere,” special issue, Discourse 28, no.1 (Winter 2006): 5–27.

- 22Bateson and Mead collected 1,288 paintings, 845 of which came from Batuan. There are 71 different painters, including children and apprentices, represented in this collection; however, only 22 of them can be considered serious painters who were part of an artistic community that painted and developed work together. Mead and Bateson were not just interested in the artworks as objects; they kept copious notes on the paintings they bought, noting when, where, and from whom they were purchased, and at times, they even collected comments from the artists about the works. While they did not write about these works explicitly, they did conduct a study of 23 painters. They developed a questionnaire on artistic training and the artists’ lives that their Indonesian assistant I Made Kaler administered to the 23 painters. See Hildred Geertz, Images of Power: Balinese Paintings Made for Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, exh. cat. (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994), 5.

- 23Geertz, Images of Power, 3.

- 24Adrian Vickers, “Balinese Modernism,” in Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia, ed. Low Sze Wee and Patrick D. Flores (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2018), 121.

- 25.Vickers, “Balinese Modernism,” 125–6.

- 26Vickers, “Balinese Modernism,” 125–6.

- 27See Margaret Mead, Letters from the Field, 1925–1975 (New York: Harper & Row, 1977).

- 28I make this claim tentatively because the exhibition at MoMA was supposedly not photographed. We cannot be certain if this was eventually staged. See box 27, folder 3, Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead Papers and the South Pacific Ethnographic Archives, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 29The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, 239. CE.MF.15.0486, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

- 30Geertz, Images of Power, 121.