Jorge Schwartz discusses the prominence of the urban in Joaquín Torres-García’s visual and literary works.

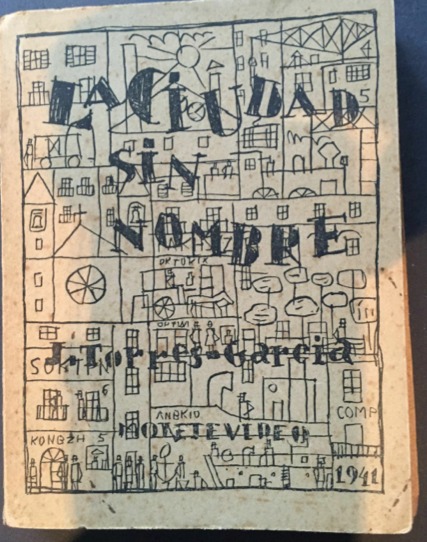

A major retrospective at MoMA, The Arcadian Modern, reveals a totalizing and structural vision of Joaquín Torres-García’s thinking, mainly through his painting, sculpture, objects, and, of particular interest to me, bibliographic production: his theoretical texts about Constructivism, autobiographical texts, manifestos, and lastly La ciudad sin nombre (The Nameless City) of 1941, a kind of illustrated novel, which has received little critical attention and is only touched upon in Sergio Chejfec’s essay in the exhibition catalogue.1Sergio Chejfec, “Torres-García´s Other Workshop” in Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2015): 176–78.

Since the beginning of Torres-García’s artistic production in Barcelona, the urban has played a prominent role in the Uruguayan painter’s pictorial work. The city—exalted by most of the historic vanguards—acquires characteristic features through it. “Lettrism,” whether understood or not, is part of Torres-García’s urban scene. It is as if the city landscape and writing make up parts of a singular visual experience. The city always appears fragmented, juxtaposed, and superimposed. The artist’s break with traditional Renaissance perspective helped him to compose the foregrounds that would become the basis for his Constructivist orthogonal paintings. The street, towering buildings, anonymous individuals or groups of people, the cafe, the streetcar, the locomotive, the steamship, the calendar, and the clock are the themes that insistently predominate his urban painting—in short, elements that when combined create an illusion of temporal acceleration due to their spatial verticality within a foreground devoid of perspective.

The clipped words, almost always indecipherable, as well as the random numbers, reveal an atomizing world whose unity is only achieved through fragmented and juxtaposed perception. Torres-García’s sojourns in Catalonia (1892–1920), New York (1920–22), and Paris (1926–32) were all rich in terms of urban issues. And if the letters and numbers constitute a constant in his paintings from this period, what is the point of mixing or joining them with painting? The intense parallelism of such distinct codes leads me to believe that his theory of Constructive Universalism underlies it. This unifying approach enabled him to coherently express different languages in a single reflexive matrix. The analogical and motivated image coexists with the arbitrary word, the product of linguistic and social norms and conventions. Actually, Torres-García’s own work is almost an ideogrammatic design, a unified aesthetic project in which it is impossible to separate one code from another.

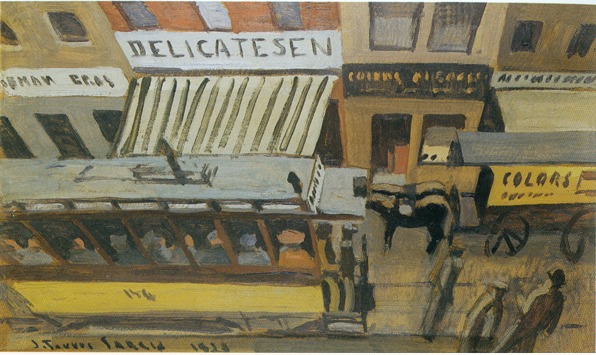

In New York Street Scene (1923), the tram’s horizontality, the anonymous individuals, and the sense of business prevail. In a space filled with signs, the tram—itself a kind of totem of modernity—appears in the foreground opposite a carriage that, pulled by two horses, flaunts the word “colors.” One mode of transport facing another, these images can be interpreted as the encounter between historic moments in dialectical opposition. On the one hand, the carriage pulled by horses is the reminiscence of a rural and agricultural universe, arrested in the clock of modernity; on the other hand, the tram in the foreground constitutes the representation of the modern machine. The word “colors” is completely dissociated from the possible contents of the carriage.

Torres-García, in his autobiography Historia de mi vida, in which he refers to himself in the third person, defines this basic process of dissociation in a clear way:

“Already in the middle of 1928 something else begins. The architectural, constructive sense of his painting produces a dissociation between drawing and color that remain as two separate entities, but in tone, color and line, and not in anything representative. These elements now will represent themselves; the whole aesthetic value of the work will reside in its free game.”2Joaquín Torres-García, Historia de mi vida (Barcelona: Paidós, 1990): 200. Originally published in 1939.

Pointing to unreal and dislocated goods might be how Torres-García escaped from the predictable and accentuated the alienation of the modern world. Moreover, the word “colors” also displaces the reader’s attention to how color is constructed within the painting itself. The focus of this scene, a view from above, makes us think of Torres-García observing and painting from a high window on the same street, in a way similar to the observer in Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Man of the Crowd,” which was analyzed by Walter Benjamin.3In Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, trans. Harry Zohn (London: NLB, 1973).

This same New York Street Scene (which was, a few years later, visited and registered by the surrealist imagination of Federico García Lorca), is filled with signs, which occupy the painting from end to end: two are legible (“delicatessen” and “colors”) and the others are not. The illegibility of this writing could be seen as a Post-Impressionist effect, whereby the emergent and suggested speed of the tram blurs the contours of the letters into patches of color. Torres-García places the painting’s viewer before a city that is meant not only to be seen, but also to be read. The reading of this city is threatened by the idea of chaos, of a missing order that is recovered later in the Constructivist project. In this sense, the blurry and fragmented words become the noise that fills Torres-García’s urban landscape.

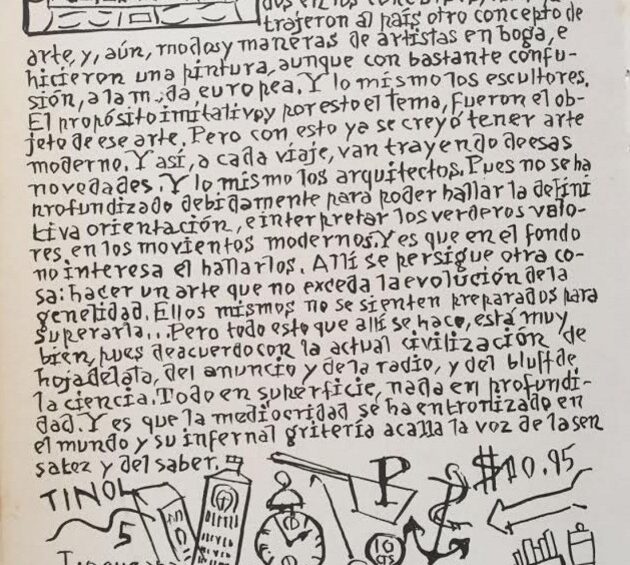

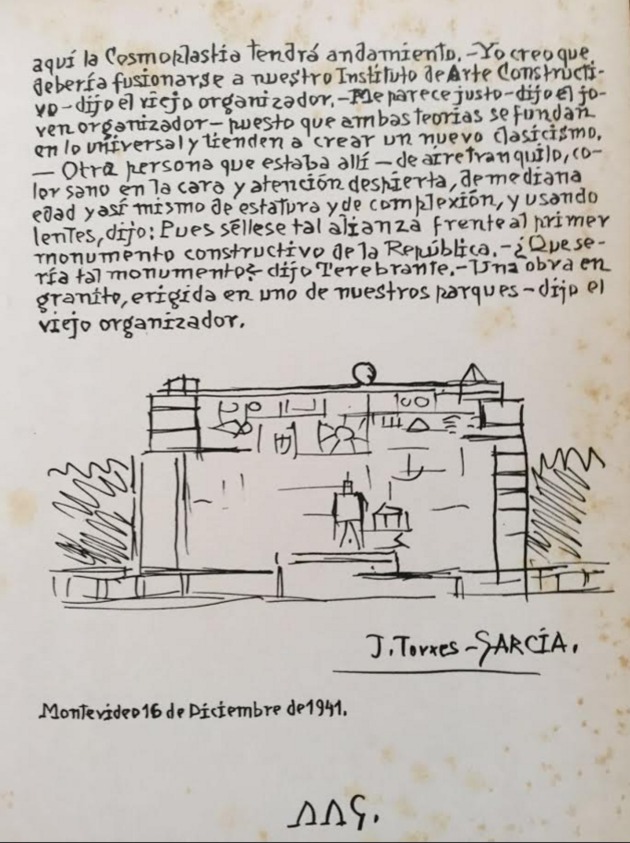

Two decades later, we find the painter in Montevideo. There he wrote The Nameless City (signed December 16, 1941 and published in Montevideo in 1941), a work of fiction of little more than one hundred unnumbered pages of text interwoven with corresponding illustrations that serve as iconic supports and references. Torres-García had returned to the city of his birth after forty-three years away, enriched by his Catalonia, New York, and Paris experiences of the 1920s and ’30s. From his critical discourse, we can discern the mentality of someone who had lived amid the historical avant-gardists and witnessed the New York Stock Exchange crisis, the emergence of fascism, the Spanish Civil War, and finally World War II, which was contemporaneous with the production of The Nameless City. Completed when he was sixty-seven, this book was prepared over the course of six hundred conferences (texts which date from 1934 to 1942) and includes 253 illustrations, which make up the theoretical monument to Constructive Universalism. Torres-García lived the most productive years of his career in Montevideo, where he founded the School of the South and the Taller Torres-García. His return, in a certain way, evokes Jorge Luis Borges, who expressed the foundational nature of his own country of origin. However, unlike Borges, who took pleasure in the poem as a gesture that culminates and crystallizes memory, Torres-García wanted to transform culture through Constructivist art. In an interview with Juan Carlos Onetti, published in the June 23, 1939 issue of the journal Marcha two years before the book was published, Torres-García said:

“I then thought of extending Constructive art across all America, going back to the pre-Columbian art forms. And not just because I thought that that is our art, but because the cataclysm that threatens Europe will sweep away what remains of its culture. And American artists would thus have no foreign models to copy. Which, undoubtedly, would be very serious. I thought, then, that the fate of America was that of constituting a refuge for culture in danger. But this idea needs to be properly understood: it is not a matter of building a gigantic museum here, but rather, of starting a new culture with new blood, another stage, in a word.”4Joaquín Torres-García, Testamento artístico (Montevideo: Biblioteca de Marcha, 1974): 3.

I believe that citing these historical facts is important for understanding Torres-García’s complex symbolic system, in which the rejection of industrial civilization prevails as does the establishment of a cosmic, total, encompassing aesthetic whose primitive basis marks a return to an Americanist thinking of the Aztec and Incan cultures (for some reason, Torres-García excluded the Mayan culture from his system)—a pre-Columbian indigenous thought that rescues the historic, sacred, quasi-religious dimension for the modern man without implying a return to the primitive. It is important to highlight that there is no indigenous culture in Uruguay—unlike so many Andean countries and Mexico—which underscores the totally utopian nature of the Torres-García project.

I cannot help but mention here how the historical avant-gardists were attracted to early cultures, beautifully evoked in Torres-García’s 1932 album Structures, pages from which are reproduced in the exhibition catalogue. And it is also worth mentioning, as Borges did at some point, that those who wrote about the gauchos were eminently urban writers, and that the gauchos themselves possibly never read. The same is true of Brazil’s greatest nineteenth-century Indianist writer, José de Alencar, who perhaps never made contact with indigenous peoples, and Vicente do Rego Monteiro, whose marajoara art was inspired by museum collections.

I will dwell briefly upon some basic elements in The Nameless City: (1) the urban as a critique of modernity, (2) aesthetics as a critical discourse, and (3) the Montevideo foundational-constructivist project.

The novel is introduced to us as a fable in motion: the arrival of a character in an unfamiliar city, his steamship journey, his visits to other cities, his final journey and farewell to the Old World, and his return to America to found a new culture and civilization. (It is interesting to note that the illustrated autobiography Historia de mi vida (History of My Life) opens with the image of a caravel, and ends with the Uruguayan flag being hoisted from the bow of a ship. And, as Luis Pérez-Oramas observed in the presentation of his exhibition, Torres-García never stopped migrating.)

The title The Nameless City unfolds in two possible singularities. On the one hand, there is the foundational aspect of a city that has yet to be named—the anticipated gesture of the demiurge, of the conqueror, or of the father, that is, the holder of the power of the word that will unveil a universe; and on the other, there is the lack of a name—or word—which translates into absence, silence, and emptiness, all products of the serial and monotonous nature of the modern city.

Although in one of her essays Beatriz Sarlo recommends forgetting Walter Benjamin because his description of the flâneur has been vulgarized, it is almost inevitable to interpret the narrator of this fiction as pure perception or consciousness amid the urban crowd of the fourmillante cité (bustling city) through which he wanders.5Beatriz Sarlo, “Olvidar a Benjamin,” Punto de Vista 53 (November 1995): 16–19. Anonymity, an essential condition of the flâneur, opens his narrative: “I just arrived in a city whose name I do not know. . . . What connects me to all this? Nothing, and everything. Nothing, because I do not know or have not heard of anyone; but everything because I am also a man.”

The sameness, the indifferent discourse, and the repetition as among the problems brought by modernity are portrayed by the flâneur/narrator: “Always through the same doors, every day, the same people enter and exit. They rout through the city, taking the same path.” Torres-Garcia, more of a philosopher than a poet—and almost more of a philosopher than a painter—describes the moment of reaching another city:

“Modern [neighborhoods] are alike everywhere: lacking personality. Trade has now unified cities. The same neon signs and the same posters; the same taste in shops and display cases; the same vehicles on the street; and the same standardized type in the passers-by.”

With the eye of an artist, the flâneur cannot cease to observe the urban landscape in terms of aesthetics, reminding us of Vibrationist paintings by Rafael Barradas, Torres-García’s great companion in youth:

“An aesthetic impression that would be extremely interesting for a modern artist. A thousand forms in ceaseless motion. Enormous surfaces with thousands of rectangular holes. Advertisements . . . We crossed a large square; trees, trams, colors in the sun, shops, cars . . . More ads: fixed, mobile, light, acoustic—always vibrating—giving no rest to sensitivity. And the countless number of vehicles: cars, trams, buses, trucks. And the human anthill on the sidewalks.” (page 11; emphasis mine)

The book’s last pages recount the flâneur/narrator’s last and founding journey home. But the return holds few surprises: “This is the Banco de la República. It looks a little like the National City Bank of New York.” Or, as he later concludes: “I am in Montevideo as I am in any other major city.”

Years before the end of World War II, the notion of planetary redundancy and the effects of what we now call market policy, globalization, and neoliberalism appear in this book, in a visionary spirit. The illusory expansion of a space ends up being reduced to a vacuum effect by the discourse of indifference itself. Modernity brings with it the abolition of space and of the sense of time.

Although Torres-García opposed Surrealism, he introduced an adman, in the same way that the Surrealists introduced the mannequin as a totem of modernity. Man as commodified object is embodied in the image of the sandwich man, present at various points in the narrative (see pages 11, 36, 74, 77, and 83):

“But, say, doesn’t it bother you to sit next to an ad-man?”

“But I am an ad, too! We are all ads of a same company.”

The continuous presence of the sandwich man in Torres-García’s narrative is nothing less than surprising. The Uruguayan painter returned to Montevideo in 1935 from Paris, the same urban realm that Benjamin would reference one year later. The brilliant essay by Susan Buck-Morss shows us that the sandwich man was a character common in the streets of Paris of that time:

“Although denigrated, the sandwich-man was a familiar figure for many Parisians in the 1930s. Human posters announced and publicized products and events (cinemas, liquidation sales) of the bourgeois consumer culture, but in spite of the uniform that was lent to them and that itself lent them a decent look, they were very closely associated with misery.”6Susan Buck-Morss, “Le Flâneur, l’homme-sandwich et la prostituée: Politique de la flânerie” in Walter Benjamin et Paris, ed. Heinz Wismann (Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1986): 369.

To Torres-García, this degraded dandy appears disguised as a walking text. What is extremely surprising is an extraordinary photograph of Torres-García, taken two decades prior to publication of the novel, in his painted overalls, which have “New York” inscribed on them (1921).7To see the image of Torres-García wearing overalls, visit www.torresgarcia.com. In his analysis of this portrait, curator Pérez-Oramas writes:

“For all the grand galas JTG attended—for one of which he designed a famous suit, overalls à la Rodchenko that made the city material on his body—the disappointment, even the failure, of his time in America is clear in a photograph of him wearing this suit, and perched on his bed, disguised as a “human ad, a decoy.”

Writing the body, or the body as writing, is already registered in Torres-García at the beginning of the 1920s, prefiguring the sandwich man in the novel, in the early 1940s, who is a kind of mobile writing within the modern city, a walking-poster victim of the new laws of the market. Despite the profusion of images in the book, the adman has not been designed.

What is it that Torres-García proposes, both in general and in this novel in particular? His is a cosmic, overall vision able to overcome the effective fragmentation, the sense of a loss of individuality, and the sense of alienation in the modern city.

The Uruguayan artist radically opposed two basic concepts imposed by modernity. The first is based on the idea of “the new” offering the possibility of renewal or redemption. To this he responds by repossessing an American tradition. The new for Torres-García means indifference. In Constructive Universalism, more precisely in lesson 30 (“The School of the South”), he states: “Our own and typical city, even though it is everywhere, is even less so, and almost not at all in certain new or modernized neighborhoods.”8In Joaquín Torres-García, Universalismo constructivo(Buenos Aires, Poseidón, 1944): 197.

Another aspect he fought fiercely is the fragmentary representation of modern art based in Cubism. Torres-García proposed and developed a totalizing art, one able to help individuals overcome their feeling of alienation, to recover their cosmic dimension in the modern world.

In the “Warning” to The Nameless City, Torres-García makes his intention very clear: making a kind of social panel or mural on which “the characters who intervene, simple dolls without human reality, are only good for materializing the drama being played out in the present world, between the spiritual, universal and eternal ideal values and collective and individual material interests in the historical [dimension]. And seeing that it is the author’s sole intent, highlighting only these two areas of struggle …”

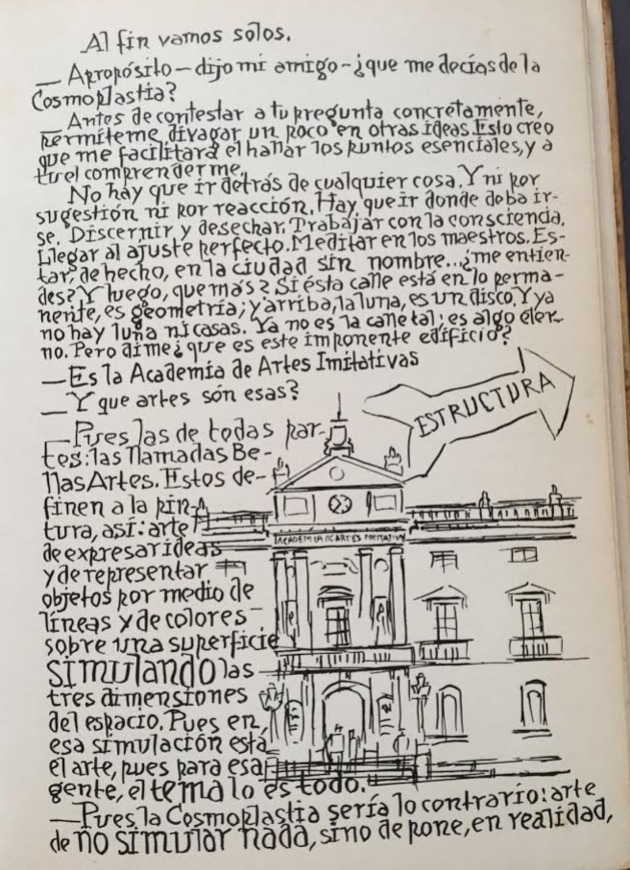

The foundational nature of the return to Montevideo is clear: “I shall explain what brings me to the country: raising art, creating a new awareness, seeking deep tradition.” Torres-García’s Universal Constructivism is a matter of joining the mythical and the ritualistic discourses in a place preceding the discovery of America—without disposing of the avant-garde. To this end, he proposes a kind of metaphysical utopia through an art that rejects naturalist imitative art through absolute abstract art without representation.9Ibid, 831.

Orthogonal design (verticals and horizontals) is the aesthetic solution (that, according to Torres-García, counters the concept of painting), whereby the surface is reduced to two dimensions (deleting perspective) and all narrative features are limited (distancing it from the typical Mexican muralism).

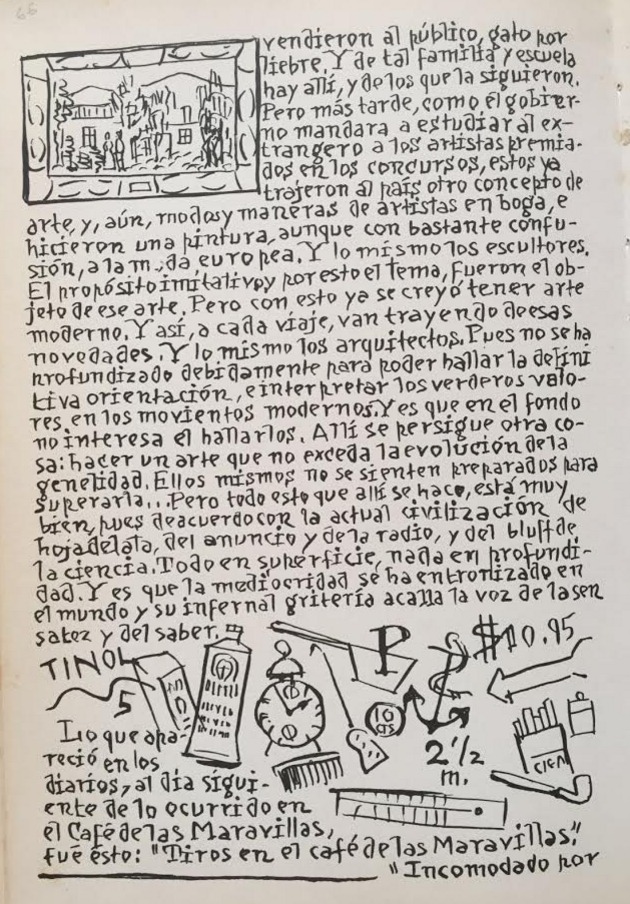

The book’s cover and some of the examples contained inside (such as those on pages 65 and 70), give us a rather rich sample of Constructive art. The last page contains a sketch that pretends to be “the first constructive monument of the Republic,” thus returning to the art of the pre-Columbian monoliths.

Only twenty of its pages are not illustrated. What is the function of the illustrations in this book, which is handwritten in print letters? On the one hand, they set the guidelines for a painter who writes and, therefore, who thinks about images. How do words and images interact in this book? Are we facing the motto Ut pictura poesis (as is painting, so is poetry)? Not exactly. I believe that Torres-García, by injecting or staggering images, incorporates them into the narrative syntagma as kind of syntax. It is indeed drawing, but without losing the conventional linearity of writing. The fast, apparently unfinished nature of the drawings suggests a sketchlike structure, fitting with the style of the travel diary and the vertigo effect caused by the modern city—a quasi-graffito of this city.

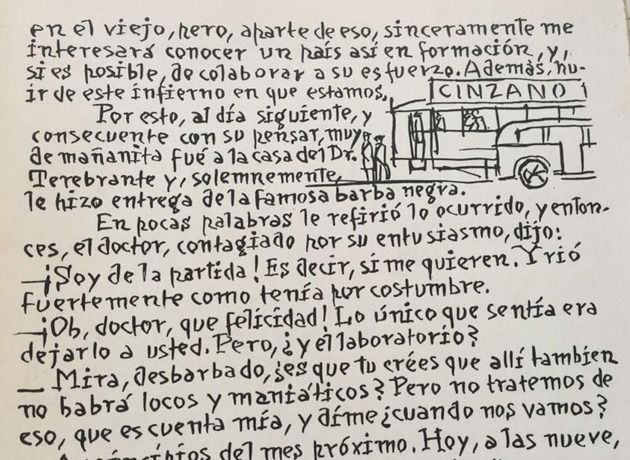

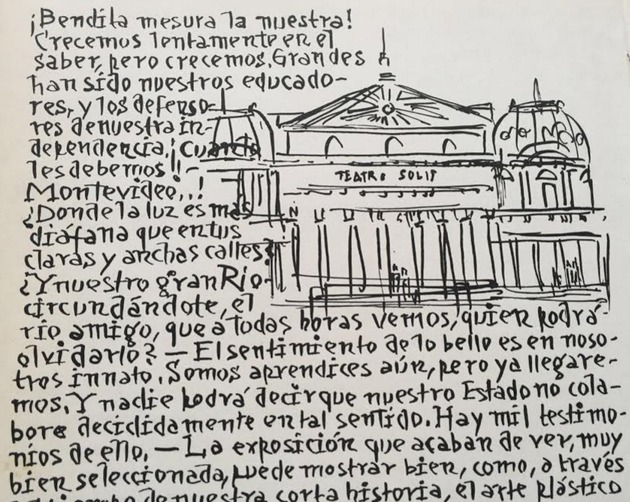

If at any point the advertisement for Cinzano on top of a tram makes us anticipate the irreversible nature of the modern city’s visual pollution from market strategies, then, on the other hand, we find a kind of local punctuation in the Teatro Solís in Montevideo), as a form of rescue from an overwhelming and depersonalizing cosmopolitanism. Likewise, we find here and there, and in contrast, remains of the neighborhood, of peripheral culture and local picturesque-ness, such as a carriage. In the urban landscape of The Nameless City these elements are kinds of relics, almost romantic reminders of an irreversible past.

Translated by John Ellis-Guardiola.

This is a shortened, translated version of the original essay, which was published in Spanish in Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos 589–590 (July–August 1999): 209–18.

- 1Sergio Chejfec, “Torres-García´s Other Workshop” in Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2015): 176–78.

- 2Joaquín Torres-García, Historia de mi vida (Barcelona: Paidós, 1990): 200. Originally published in 1939.

- 3In Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, trans. Harry Zohn (London: NLB, 1973).

- 4Joaquín Torres-García, Testamento artístico (Montevideo: Biblioteca de Marcha, 1974): 3.

- 5Beatriz Sarlo, “Olvidar a Benjamin,” Punto de Vista 53 (November 1995): 16–19.

- 6Susan Buck-Morss, “Le Flâneur, l’homme-sandwich et la prostituée: Politique de la flânerie” in Walter Benjamin et Paris, ed. Heinz Wismann (Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1986): 369.

- 7To see the image of Torres-García wearing overalls, visit www.torresgarcia.com.

- 8In Joaquín Torres-García, Universalismo constructivo(Buenos Aires, Poseidón, 1944): 197.

- 9Ibid, 831.