Debates around the ownership of cultural heritage and decolonizing museums have become increasingly visible and polarizing in the public domain, leading to attempts to redefine the term “museum” itself.1The International Council of Museums (ICOM) Extraordinary General Assembly approved the following new definition of “museum” at the 26th ICOM General Conference held in Prague in August 2022: “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.” “ICOM approves a new museum definition,” ICOM website, https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-approves-a-new-museum-definition/. It is evident that large-scale Imperial looting campaigns such as the “Sack of Benin” (1897), the “Looting of the Summer Palace” (1860), and the “Pillage of Sri Rangapattana” (1799) have received sustained scholarly attention.2See, for example, Dan Hicks, The Brutish Museum: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution (Pluto Press, 2020); Louise Tythacott, “The Yuanmingyuan and its Objects” in Collecting and Displaying China’s “Summer Palace” in the West: The Yuanmingyuan in Britain and France, ed. Louise Tythacott (Routledge, 2018), 1-39; James L. Hevia, English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century China (Duke University Press, 2003); Annie E. Coombes, Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England (Yale University Press, 1994); Richard H. Davis, Lives of Indian Images (Princeton University Press, 1997); Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (Princeton University Press, 1996); and Carol A. Breckenridge, “The Aesthetics and Politics of Colonial Collecting: India at World Fairs,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 31, no. 2 (1989): 195–216. These seminal events of British looting have been extensively researched, remain under public scrutiny, and are firmly lodged in museum agendas. However, relatively little attention has been paid (either in the public domain or museums) to the invasion of Tibet in 1903–4 by Colonel Francis Younghusband (1863–1942), even though, when compared with Benin, “more troops were involved in his mission, a larger number of buildings were raided, and greater quantities of material were removed.”3Clare E. Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet (University of Chicago Press, 2012), 53. Looting during Younghusband’s military expedition has been acknowledged in the text labels of a few permanent museum displays, including in the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), and the World Museum in Liverpool. Recent references include a Tibet-focused case display in the exhibition Hew Locke: what have we here?, October 17, 2024–February 9, 2025, British Museum, London, and Sathnam Sanghera, Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain (Viking, 2021). This extreme case of British looting has received comparatively limited academic attention compared to other contexts.4Exceptions include Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World; Alex McKay, “The British Invasion of Tibet, 1903–04,” Inner Asia 14, no. 1 (2012): 5–25; Tim Myatt, “Trinkets, Temples, and Treasures: Tibetan Material Culture and the 1904 British Mission to Tibet,” Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines 21, no. 2(2011): 123-153; Inbal Livne, “Hostage to Fortune or a Considered Collection? The Tibetan Collections at National Museums Scotland and their Collections,” Journal of Museum Ethnography 23 (2010): 84-97; Michael Carrington, “Officers, Gentlemen and Thieves: The Looting of Monasteries during the 1903/4 Younghusband Mission to Tibet,” Modern Asian Studies 37, no. 1(2003): 81–109; and Jane C. Moore, “Colonial Collecting: A study of the Tibetan collections at Liverpool Museum – Cultural Encounters, Patterns of Acquisition and the Ideology of Display” (PhD diss., University of Liverpool, 2001).

While Tibet has ceased to exist as an independent nation, Tibetan material heritage continues to be extensively circulated, collected, displayed, and interpreted in museums, the art market, and academia (fig. 1). Exhibitions of “Tibetan art” remain a regular occurrence in the exhibition circuit. Moreover, Tibetan objects are omnipresent in auctions of Asian art every season at all the major international auction houses and continue to fetch record prices in the global art market. This hypervisibility of Tibetan objects in museums and the market raises a fundamental question: Why is so much of Tibet’s material heritage circulating outside Tibet, displaced from its original place of worship and practice, and so far removed from Tibetans? This phenomenon is succinctly captured by Clare Harris, who notes, “The bulk of Tibet’s portable cultural heritage has been retained everywhere other than Tibet, and is now most readily at the disposal of everyone other than Tibetans.”5Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 5. Hence, further attention to the provenance of Tibetan collections dispersed across the world in public and private collections is warranted, particularly to assess the colonial entanglement of sacred Tibetan objects.

The complex colonial entanglement of museum collections in the Global North has led to a growing body of scholarship suggesting that museums must engage with the communities to which these objects originally belonged as a form of symbolic reparation and restorative justice.6See, for example, Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown, eds., Museums and Source Communities: A Routledge Reader (Routledge, 2003). This practice has been gaining recognition and momentum, with various attempts to “transform” the museum or, at the very least, alter the relationship between the museum and “communities of origin,” a move that has been deemed “one of the most important developments in the history of museums.”7Peers and Brown, Museums and Source Communities, 1. Peers and Brown create a broad definition for “source communities” / “communities of origin” that includes groups from whom the objects were collected in the past and their present descendants. Ibid., 2. However, to this day, there is an acute absence of Tibetans in museums, whether as curators, interpreters, collaborators, or other agents in the construction of knowledge and representation or as members of the audience for museum displays.

“Doubly colonial” Tibet: An Inheritance of Loss

In her seminal text The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet (2012), Harris highlights that the hypervisibility of Tibetan objects is due to the extensive scale of displacement of Tibetan heritage from the Tibetan landscape and people through repeated waves of extraction of objects in a “doubly colonial” context, that of both British and Chinese looting in the twentieth century.8Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 5–6. She articulates that Tibet is a possibly unique example of being “doubly colonial” as before the People’s Republic of China assimilated Tibet, it witnessed a British colonialist intervention in the form of the Younghusband “Expedition” of 1903–4. These repeated waves of pillaging have physically deprived Tibet of significant quantities of its material heritage, which is now found primarily in Western or Chinese museums and private collections worldwide, not in Tibet itself.

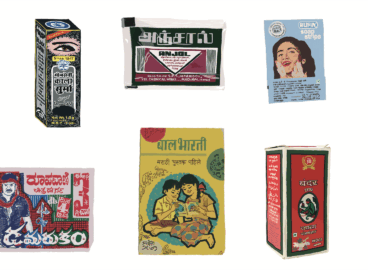

The Younghusband Mission was a British military campaign sanctioned by Lord Curzon (1859–1952), who served as viceroy of India (1898–1905), due to rising anxieties over perceived Russian influence in Tibet. There was no intention to annex Tibet into the British Empire, but the aim was to force the Tibetans to end their suspected dealings with Russia and to establish a dominant British influence in Tibet, an agenda some have deemed “almost entirely bogus.”9Charles Allen, Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa (John Murray, 2004), 1. Strikingly, the Younghusband Mission was primarily a military campaign, deploying the latest technology available to the British at the time: four field guns firing shrapnel shells and two Maxim machine guns capable of firing 760 rounds per minute. To illustrate the scale of senseless violence and plunder that took place during this invasion, let’s revisit the infamous “Battle of Guru,” known among Tibetans as the “Massacre of Chumik Shenko” (fig. 2).

On March 31, 1904, the incursion of British forces was halted by Tibetan forces in the valley of Guru in southern Tibet. According to Tibetan sources, the British proposed that as a precondition for negotiations, all Tibetan soldiers must unload their weapons and extinguish the fuses of their muskets.10Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, trans. Derek F. Maher (Brill, 2010), 673. While preparations for negotiations were taking place, British forces strategically positioned their machine guns on nearby hills and surrounded the Tibetan army from three directions. According to Tibetan government records, when the British opened fire, 523 Tibetans were killed and 300 more were wounded.11Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, 674. A field report telegram by Brigadier General Macdonald also puts the number of Tibetan casualties at around 500, but some recent estimates put the number at around 700. See Henrietta Lidchi and Rosanna Nicholson, “Seeing Tibet Through Soldiers’ Eyes: Photograph Albums in Regimental Museums,” in Dividing the Spoils: Perspectives on Military Collections and the British Empire, ed. Henrietta Lidchi and Stuart Allan (Manchester University Press, 2020), 147. While there is debate about what started the skirmish, it is apparent that the British army used a strategic maneuver to outflank and “box in” the Tibetan army, attacking them from three sides and firing over 15,000 rounds of ammunition on retreating Tibetans.12According to the after-action report by Brigadier General Macdonald. Shubhi Sood, Younghusband, The Troubled Campaign (India Research Press, 2005), 66. British forces pursued Tibetans for 12 miles and continued to kill and maim them.13Allen, Duel in the Snows, 122. After this massacre, many battle trophies were collected from the bodies of the dead or from surrendered Tibetan soldiers, including earrings, gau (box amulets), bandolier belts, weapons, and clothing.

After seizing key strategic positions in Tibet, such as the monastery-city of Gyantse, British officers committed what Patrick French has termed “casual robbery” in deserted monasteries or houses.14Patrick French, Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer (HarperCollins, 1994), 228. What began as collecting battle trophies at Guru became frenzied looting among the ranks at every available opportunity, but the expedition later followed a formalized protocol to sift through the material, which would, in appearance, be “a more reputable form of collecting for intellectual pursuits.”15Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 63. According to Harris, the Younghusband Mission is significant because it created a desire and appetite for Tibetan objects in the market.16Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 54. Even before Younghusband’s military campaign reached its conclusion in Lhasa, a steady stream of looted Tibetan objects had been trickling into Great Britain, some of which fetched high prices at Christie’s auction house in London.17Allen, Duel in the Snows, 287.

The state-led destruction of Tibetan cultural heritage peaked later, during the Cultural Revolution (1967–77), when according to Tibetan sources, more than 6,000 Tibetan temples and monasteries were ransacked and partially or fully destroyed mainly by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and agents of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).18According to various Tibetan sources, including the often-cited 1962 report on the conditions inside Tibet by the Tenth Panchen Lama, “70,000 Character Petition,” which was submitted to the Chinese government. Recent publications have noted “active participation” by Tibetans as agents of the CCP in the destruction of temples and monasteries. See, for example, Wang Lixiong and Tsering Shakya, The Struggle for Tibet (Verso, 2009), 61. During this purge of Tibetan culture, sacred Buddhist sites such as the Jokhang temple in Lhasa were desecrated (fig. 3). This systematic desecration was through the destruction of venerated sacred images of Buddha, Bodhisattvas and protective spirits; the burning of precious manuscripts, manuscript printing blocks and thangka paintings as cooking fuel; and the turning of the area into a pig slaughterhouse and toilet by the PLA Garrison Command.19Tsering Woeser, Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution, ed. Robert Barnett, trans. Susan T. Chen (Potomac Books, 2020), 75. Sam van Schaik notes this destruction was a “carefully planned operation” as each site was first inventoried, with “all precious stones and metal objects carefully labelled and prepared for transportation to Beijing.”20Sam van Schaik, Tibet: A History (Yale University Press, 2011), 245. The desecration and destruction of the Jokhang temple are illustrative of what happened to many sacred temples and monasteries all over Tibet.

In an overview of different case studies on plundered cultural properties for the International Committee of Museums (ICOM) publication Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods: The Global Challenge of Protecting the World’s Heritage (2015), Sam Hardy argues that the loss and destruction of Tibetan heritage under the Chinese state was “incalculable both in terms of culture and in terms of sheer quantity.”21Sam Hardy, “The Conflict Antiquities Trade: A Historical Overview,” in Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods: The Global Challenge of Protecting the World’s Heritage, ed. France Desmarais (ICOM, 2015), 27. For instance, in the 1990s, monasteries in Tibet were targeted by Chinese gangs who “killed monks in their violent attempts to remove statues from monasteries” so that they could profit from the appetite for Tibetan material heritage in the global art market.22Neil Brodie, “Report on Who Owns Culture? International Conference on Cultural Property and Patrimony conference at Columbia University, 15-17 April 1999,” Culture Without Context: The Newsletter of the Illicit Antiquities Research Centre 4 (1999), 30. In 2008, the Chinese police confiscated cultural assets from Tibetan communities as a punishment for the Tibetan uprising, and this was evidenced by a marked flow of Tibetan cultural material onto the antiquities market.23Hardy, “The Conflict Antiquities Trade,” 27.

The destruction and dispossession of Tibetan material heritage has been acutely experienced by Tibetan refugees, who were forced to sell their material heirlooms to survive and sustain themselves. The exodus of refugees from Tibet in 1959 has only added further symbolic capital to Tibetan material culture.24Clare Harris, In the Image of Tibet: Tibetan Painting after 1959 (Reaktion Books, 1999), 36. Despite the mainstreaming of debates around decolonizing museums and restitution of looted heritage, the case of Tibet in museums has remained conspicuously absent from both postcolonial and decolonial discourse.25This can be attributed to various complex factors, including the suppression and invisibility of the contentious history of the Younghusband mission, the complexities and contentions surrounding the geopolitical status of Tibet, and historical distancing. This is also attributed to the relative lack of education and public debate in the United Kingdom (until very recently) on the history of the British Empire, particularly in South Asia. Recent debates in museums about colonial collections have also been driven by members of the South Asian and African diaspora communities residing in the United Kingdom. However, Tibetans are not present in Western nations in sufficiently large numbers, which hampers their capacity to tell this story (and gain public momentum around them), and they lack agency in museums and other knowledge-producing institutions. Tibetans remain completely marginalized within such museum agendas and discussions, giving rise to a paradox that while objects from Tibet are much desired and welcomed in museums, Tibetan people are not.26Among the few notable exceptions is the initiatives at the Pitt Rivers Museum, which since 2003 has hosted an unprecedented series of residencies for contemporary Tibetan artists and a collaborative research project titled Tibet Visual History 1920–1950, through which Tibetans have actively engaged with museum collections and archives. Other exceptions include two community-facing workshops at the Horniman Museum and Gardens. The Horniman hosted these workshops for the Tibetan community in London as part of the Art Council-funded project Collections, Peoples, Stories: Tibetan Food and Feasting Workshop in 2013. Thus, the fractures in the geopolitical and cultural identity of the Tibetan people are further amplified as they endure the loss not only of their land but also of their material heritage.

Uncovering the “Debt of Truth” in Tibetan Collections

Among the vast Tibetan collections dispersed across museums and private collections in the United Kingdom lie the muted and suppressed histories of violence and plunder that took place during the Younghusband invasion of Tibet, often embedded in the object’s very materiality. This was particularly evidenced by a gau pierced by a bullet and now held in the Cheltenham Museum and Art Gallery in Gloucestershire, which Harris argues was collected as a battle trophy by the British army.27Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 26. Another gau riddled with a bullet hole (fig. 4) was discovered in the collection of the National Museums Scotland.28Inbal Livne, “Hostage to Fortune or a Considered Collection? The Tibetan Collections at National Museums Scotland and their Collections,” Journal of Museum Ethnography 23 (2010): 84-97. The late historian of Tibetan art John Clarke highlights that for a gau to be effective, it must be in contact with the body.29John Clarke, “Ga’u, The Tibetan Amulet Box,” Arts of Asia 31, 3(2001), 45. For this reason, although we do not have Tibetan bodies to examine to uncover the violence that took place during Younghusband’s military campaign in Tibet, the gau becomes a proxy for Tibetan bodies and lives in material form. During my collections research at various museums in the United Kingdom, I have encountered a vast number of gau and even if only a minority of them were removed from the bodies of dead Tibetans, this still potentially represents hundreds of lost Tibetan lives (fig. 5).

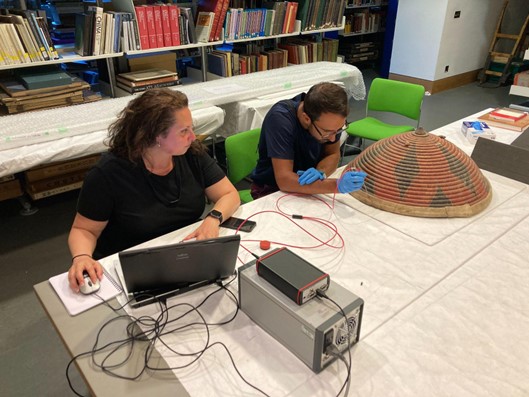

This loss of life can be even more “explicitly” evidenced through Tibetan objects I encountered during my doctoral fieldwork that have spots of what could be blood. I observed such spots on two objects, both with a direct Younghusband provenance—a gau in the World Cultures collection of the National Museums Liverpool and a wicker shield from the British Museum.30See “Amulet box / ga’u,” acc. no. 54.85.55, National Museums Liverpool, https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/amulet-box-gau-21; and “shield,” museum no. 1905,0519.169, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1905-0519-169. The gau (fig. 6) houses a tsa-tsa (clay tablet) of Mahakala and a folded kha-btags (white silk scarf). The handwritten label reads, “Charm against bullet—taken from the body of a dead Tibetan at Dongste monastery by Major.”31The Major’s name is withheld from the records, and it is difficult to discern the field “collector” as ten officers with the rank of Major were attached to Younghusband’s military campaign in Tibet. The label refers to a Geluk monastery at Drongtse (‘brong-rtse), near Gyantse, that was founded in 1442. On examining this gau, I observed a sizeable, red spot on the object’s textile amulet (srung-nga) component. I thought this stain was possibly blood due to the acquisition circumstances (it was taken from a dead Tibetan’s body) and the knowledge of how the amulet is traditionally worn across the body. I immediately requested testing, and the in-house investigation was conducted by senior organics conservator Tracey Seddon. Due to the museum’s hesitance to authorize destructive sampling, we discussed and explored alternative, nondestructive analytical procedures. However, such methods were inconclusive.32It was tested via Hemident™ McPhail’s Reagent, a presumptive test for identifying mammal blood. The result was possibly positive for blood but barely perceptible due to the tiny sample size. Joanne Dyer and Diego Tamburini from the Department of Scientific Research at the British Museum also conducted noninvasive testing on the shield, with FORS (Fiber Optic Reflectance spectroscopy) as the only available in-house option (fig. 7). Preliminary tests on both objects were unable to conclusively scientifically verify the presence of blood, and multiple experts, including the team at the British Museum, concluded that the only viable route would be to conduct proteomics analysis (a cellular examination of proteins), which would require destructive sampling.33I would like to thank Tracey Seddon (National Museums Liverpool), Jeremy Uden (Pitt Rivers Museum), Fiona Brock (Cranfield Forensic Institute), and the team at the British Museum (Imma Ramos, Joanne Dyer, and Diego Tamburini) for their time and support of this inquiry.

Even with the small sample size of the collections review during my doctoral research, I uncovered two objects of potential significance at the British Museum whose origins were inscribed on them—a kapala (fig. 8) and a helmet (fig. 9).34Museum nos. 1905,0519.82 and 1905,0519.167. Both had been “collected” by Major H. A. Iggulden, a member of the Younghusband Mission. Upon examination, I observed that “Palkhor Chode” had been inscribed on the base of the kapala. This refers to Pelkhor Chode, an important monastic complex in Gyantse (located in the historical Tsang province of Tibet), which was attacked and occupied by the British in 1904.35The Gyantse dzong (fort) became a site for mounting Tibetan resistance to halt further incursion of British troops into Tibet. British troops defeated the Tibetan army and occupied the Gyantse dzong but subsequently lost it to Tibetan reinforcements and were forced to lay siege to it again. During this second siege, which lasted two months, the British troops also stormed “hostile” monasteries in the surrounding district and “rescued” Tibetan objects from those sites. Carrington, “Officers, Gentlemen and Thieves,” 97. The looted sites include the Tsechen (rtse-chen) monastery, the Nenying (gnas-snying) monastery, the Drongtse (‘brong-rtse) monastery, and the family manor of the aristocratic Pala (pha-lha) family. I argue that this kapala was inscribed by the field “collector” to mark the origins of this battle trophy collected from Gyantse. The helmet revealed a Tibetan inscription rgyal-tse (Gyantse), which is accompanied by what appears to be the Tibetan numeral seven (༧). I believe that these objects were removed and taken from the Pelkhor Chode monastery (or Gyantse dzong) by Major Iggulden, but were transcribed by two different types of agents: Indigenous (Tibetan) and colonial (British). However, it is noteworthy that the museum recorded neither of these easily legible inscriptions, particularly considering they reveal direct provenance. These gaps in the museum database are not highlighted to criticize the specific institutions, as this is symptomatic of the broader sector, but rather to show how such gaps could become focal points for museums to coproduce knowledge with living members of the Tibetan community, rather than re-amplifying what was said or done by British officers.

Considering the limitations in archival information (notably on early Tibetan collections), and more importantly, due to suppressed and silenced histories in the colonial archive, new modes of scientific inquiry on Tibetan objects could be deployed to uncover “truths” in the collection. Such inquiries can make the hidden violence of Tibetan objects explicit, which historian Achille Mbembe calls a “debt of truth” that museums should address.36Achille Mbembe, “Thoughts on the Planetary: An Interview with Achille Mbembe,” in Decolonising the Neoliberal University: Law, Psychoanalysis and the Politics of Student Protest, ed. Jaco Barnard-Naude (Birkbeck Law Press, 2021). This case study also highlights the inherent conflict between institutional guidelines that seek to preserve the physical integrity of objects and the necessity of conducting tests that generally require destructive sampling.37There are also the ethics of destructive sampling and scientific testing on sacred objects from a Tibetan Buddhist perspective, which are subjects of my current research. Reflecting on the histories of the museumification of Tibet’s material heritage, venerated Tibetan sacred images and objects (such as gau) have been emptied of their sacral contents (gzungs-gzhug) in the name of scientific inquiry and thangka paintings have been radically altered with their textile borders (gong-gsham) removed to elevate them as “fine art.”38Annie Hall, “A case study on the ethical considerations for an intervention upon a Tibetan religious sculpture,” The Conservator 28, no. 1 (2004): 66-73; Titika Malkogeorgou, “Everything Judged on Its Own Merit? Object Conservation and the Secular Museum,” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 10, no. 2 (2012): 1–7, http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021203; and Gregory Grieve, “The Rubin Museum of Art: Re-framing Religion for Aesthetic Spirituality,” Journal of Material Religion 3 (2006): 130-135. Considering sacred Tibetan objects have been subjected to such forms of museal violence across different institutions, museums must reconsider and prioritize such modes of inquiry that would uncover the colonial violence that caused the object to be in the museum’s collection in the first place.

Reanimating Tibet in the Museum

While Tibetans have had limited agency in how much of Tibet’s portable heritage was deposited in museums across the world through “doubly colonial” extractive regimes, it can be argued that the objects have only survived significant periods of destruction due to their “museumization.” However, as is apparent, there are substantial gaps in the knowledge and provenance around/of Tibetan collections across institutions. To address these gaps and offer an antidote to the dislocation and destruction of Tibetan cultural heritage, museums must engage with Tibetans and reconnect these objects to the community (fig. 10).39My praxis-based research continues to focus on creating sustainable and equitable relationships between museums and members of the transnational Tibetan diaspora. Figure 10 is from a session held at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford in July 2022, during which select Tibetan stakeholders from my doctoral research were invited to participate in discussions at the Pitt Rivers Museum, the British Museum, and the V&A. To begin addressing the colonial entanglement, these Tibetan collections could serve as focal points for long-term and sustainable engagement between museums and Tibetans. Besides tackling issues surrounding the lack of Tibetan agency and the acute absence of Tibetan voice(s) in museums, this could give rise to innovative approaches to creating new knowledge and working with Tibetan collections. However, Tibet’s complex and contested nature raises a foundational question: Who can represent Tibetan interests in museums and in the related “authorized heritage discourse”?40According to Laurajane Smith, heritage becomes “a discourse about and through which identity claims are re/created and legitimised – it is not a static process but one in which identity is continually remade and expressed to meet the current and changing needs of individual, community or nation”. Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (Routledge, 2006), 302.

While working with communities has become increasingly mainstream across the museum and heritage sector in the United Kingdom (and beyond), prevailing practices and discourse primarily focus on the outputs of community engagement or collaboration. As noted by some scholars, there is a need to move beyond the prevalent “black box” approach to community engagement and pivot the focus from the products of consultation or collaboration to its underlying process and methodologies.41See, for example, Ann McMullen, “The Currency of Consultation and Collaboration,” Museum Anthropology Review 2, no. 2 (2008): 54–87; Bernadette Lynch, “Collaboration, contestation, and creative conflict: On the efficacy of museum/community partnerships,” in Redefining Museum ethics, ed. J. Marstine (Routledge, 2011), 146–163; and Bryony Onciul, Museums, Heritage and Indigenous Voice: Decolonizing Engagement (Routledge, 2015). As museums become increasingly social spaces and undertake more extensive consultation and collaboration initiatives, divergent actors and groups will inevitably emerge to compete for the role of representing a “community of origin.” Hence, the museum will have to mediate between these competing groups and subsets of communities. Considering the cultural and geopolitical implications and shifting goalposts in ethics, community-oriented museum practices must be grounded in sustained research, methodology, and ethical and critical precision, particularly when the ownership of material heritage is contested and its provenance is complex. My work remains grounded in a simple idea—let’s not propose or conceive of solutions to problems we don’t fully understand, especially if the decisions are irreversible and permanent, such as restitution. Museums (and academics) could instead try to create conditions or spaces that allow communities to undertake “slow agentive decision-making” in choices concerning the future of their heritage accessioned in Western museums, which will have long-lasting impact and significance.42Catherine Massola, “Community Collections: Returning to an (Un)Imagined Future,” Museum Anthropology 46, no. 1 (2023): 59–69, https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12267. In such slow, agentive processes, it can become more apparent how sub-state actors such as Indigenous/historically marginalized communities could assert agency in authorized heritage discourse currently dominated by (direct and indirect) state actors. It’s evident that the complex and contested case of Tibet in museums requires a nuanced research-led approach. Perhaps this is a true litmus test for the decolonial agendas of the museum and heritage sector?

- 1The International Council of Museums (ICOM) Extraordinary General Assembly approved the following new definition of “museum” at the 26th ICOM General Conference held in Prague in August 2022: “A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing.” “ICOM approves a new museum definition,” ICOM website, https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-approves-a-new-museum-definition/.

- 2See, for example, Dan Hicks, The Brutish Museum: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution (Pluto Press, 2020); Louise Tythacott, “The Yuanmingyuan and its Objects” in Collecting and Displaying China’s “Summer Palace” in the West: The Yuanmingyuan in Britain and France, ed. Louise Tythacott (Routledge, 2018), 1-39; James L. Hevia, English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century China (Duke University Press, 2003); Annie E. Coombes, Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England (Yale University Press, 1994); Richard H. Davis, Lives of Indian Images (Princeton University Press, 1997); Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India (Princeton University Press, 1996); and Carol A. Breckenridge, “The Aesthetics and Politics of Colonial Collecting: India at World Fairs,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 31, no. 2 (1989): 195–216.

- 3Clare E. Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet (University of Chicago Press, 2012), 53. Looting during Younghusband’s military expedition has been acknowledged in the text labels of a few permanent museum displays, including in the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), and the World Museum in Liverpool. Recent references include a Tibet-focused case display in the exhibition Hew Locke: what have we here?, October 17, 2024–February 9, 2025, British Museum, London, and Sathnam Sanghera, Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain (Viking, 2021).

- 4Exceptions include Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World; Alex McKay, “The British Invasion of Tibet, 1903–04,” Inner Asia 14, no. 1 (2012): 5–25; Tim Myatt, “Trinkets, Temples, and Treasures: Tibetan Material Culture and the 1904 British Mission to Tibet,” Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines 21, no. 2(2011): 123-153; Inbal Livne, “Hostage to Fortune or a Considered Collection? The Tibetan Collections at National Museums Scotland and their Collections,” Journal of Museum Ethnography 23 (2010): 84-97; Michael Carrington, “Officers, Gentlemen and Thieves: The Looting of Monasteries during the 1903/4 Younghusband Mission to Tibet,” Modern Asian Studies 37, no. 1(2003): 81–109; and Jane C. Moore, “Colonial Collecting: A study of the Tibetan collections at Liverpool Museum – Cultural Encounters, Patterns of Acquisition and the Ideology of Display” (PhD diss., University of Liverpool, 2001).

- 5Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 5.

- 6See, for example, Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown, eds., Museums and Source Communities: A Routledge Reader (Routledge, 2003).

- 7Peers and Brown, Museums and Source Communities, 1. Peers and Brown create a broad definition for “source communities” / “communities of origin” that includes groups from whom the objects were collected in the past and their present descendants. Ibid., 2.

- 8Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 5–6.

- 9Charles Allen, Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa (John Murray, 2004), 1.

- 10Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, trans. Derek F. Maher (Brill, 2010), 673.

- 11Shakabpa, One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet, 674. A field report telegram by Brigadier General Macdonald also puts the number of Tibetan casualties at around 500, but some recent estimates put the number at around 700. See Henrietta Lidchi and Rosanna Nicholson, “Seeing Tibet Through Soldiers’ Eyes: Photograph Albums in Regimental Museums,” in Dividing the Spoils: Perspectives on Military Collections and the British Empire, ed. Henrietta Lidchi and Stuart Allan (Manchester University Press, 2020), 147.

- 12According to the after-action report by Brigadier General Macdonald. Shubhi Sood, Younghusband, The Troubled Campaign (India Research Press, 2005), 66.

- 13Allen, Duel in the Snows, 122.

- 14Patrick French, Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer (HarperCollins, 1994), 228.

- 15Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 63.

- 16Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 54.

- 17Allen, Duel in the Snows, 287.

- 18According to various Tibetan sources, including the often-cited 1962 report on the conditions inside Tibet by the Tenth Panchen Lama, “70,000 Character Petition,” which was submitted to the Chinese government. Recent publications have noted “active participation” by Tibetans as agents of the CCP in the destruction of temples and monasteries. See, for example, Wang Lixiong and Tsering Shakya, The Struggle for Tibet (Verso, 2009), 61.

- 19Tsering Woeser, Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution, ed. Robert Barnett, trans. Susan T. Chen (Potomac Books, 2020), 75.

- 20Sam van Schaik, Tibet: A History (Yale University Press, 2011), 245.

- 21Sam Hardy, “The Conflict Antiquities Trade: A Historical Overview,” in Countering Illicit Traffic in Cultural Goods: The Global Challenge of Protecting the World’s Heritage, ed. France Desmarais (ICOM, 2015), 27.

- 22Neil Brodie, “Report on Who Owns Culture? International Conference on Cultural Property and Patrimony conference at Columbia University, 15-17 April 1999,” Culture Without Context: The Newsletter of the Illicit Antiquities Research Centre 4 (1999), 30.

- 23Hardy, “The Conflict Antiquities Trade,” 27.

- 24Clare Harris, In the Image of Tibet: Tibetan Painting after 1959 (Reaktion Books, 1999), 36.

- 25This can be attributed to various complex factors, including the suppression and invisibility of the contentious history of the Younghusband mission, the complexities and contentions surrounding the geopolitical status of Tibet, and historical distancing. This is also attributed to the relative lack of education and public debate in the United Kingdom (until very recently) on the history of the British Empire, particularly in South Asia. Recent debates in museums about colonial collections have also been driven by members of the South Asian and African diaspora communities residing in the United Kingdom. However, Tibetans are not present in Western nations in sufficiently large numbers, which hampers their capacity to tell this story (and gain public momentum around them), and they lack agency in museums and other knowledge-producing institutions.

- 26Among the few notable exceptions is the initiatives at the Pitt Rivers Museum, which since 2003 has hosted an unprecedented series of residencies for contemporary Tibetan artists and a collaborative research project titled Tibet Visual History 1920–1950, through which Tibetans have actively engaged with museum collections and archives. Other exceptions include two community-facing workshops at the Horniman Museum and Gardens. The Horniman hosted these workshops for the Tibetan community in London as part of the Art Council-funded project Collections, Peoples, Stories: Tibetan Food and Feasting Workshop in 2013.

- 27Harris, The Museum on the Roof of the World, 26.

- 28Inbal Livne, “Hostage to Fortune or a Considered Collection? The Tibetan Collections at National Museums Scotland and their Collections,” Journal of Museum Ethnography 23 (2010): 84-97.

- 29John Clarke, “Ga’u, The Tibetan Amulet Box,” Arts of Asia 31, 3(2001), 45.

- 30See “Amulet box / ga’u,” acc. no. 54.85.55, National Museums Liverpool, https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/amulet-box-gau-21; and “shield,” museum no. 1905,0519.169, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1905-0519-169.

- 31The Major’s name is withheld from the records, and it is difficult to discern the field “collector” as ten officers with the rank of Major were attached to Younghusband’s military campaign in Tibet.

- 32It was tested via Hemident™ McPhail’s Reagent, a presumptive test for identifying mammal blood. The result was possibly positive for blood but barely perceptible due to the tiny sample size.

- 33I would like to thank Tracey Seddon (National Museums Liverpool), Jeremy Uden (Pitt Rivers Museum), Fiona Brock (Cranfield Forensic Institute), and the team at the British Museum (Imma Ramos, Joanne Dyer, and Diego Tamburini) for their time and support of this inquiry.

- 34Museum nos. 1905,0519.82 and 1905,0519.167.

- 35The Gyantse dzong (fort) became a site for mounting Tibetan resistance to halt further incursion of British troops into Tibet. British troops defeated the Tibetan army and occupied the Gyantse dzong but subsequently lost it to Tibetan reinforcements and were forced to lay siege to it again. During this second siege, which lasted two months, the British troops also stormed “hostile” monasteries in the surrounding district and “rescued” Tibetan objects from those sites. Carrington, “Officers, Gentlemen and Thieves,” 97. The looted sites include the Tsechen (rtse-chen) monastery, the Nenying (gnas-snying) monastery, the Drongtse (‘brong-rtse) monastery, and the family manor of the aristocratic Pala (pha-lha) family.

- 36Achille Mbembe, “Thoughts on the Planetary: An Interview with Achille Mbembe,” in Decolonising the Neoliberal University: Law, Psychoanalysis and the Politics of Student Protest, ed. Jaco Barnard-Naude (Birkbeck Law Press, 2021).

- 37There are also the ethics of destructive sampling and scientific testing on sacred objects from a Tibetan Buddhist perspective, which are subjects of my current research.

- 38Annie Hall, “A case study on the ethical considerations for an intervention upon a Tibetan religious sculpture,” The Conservator 28, no. 1 (2004): 66-73; Titika Malkogeorgou, “Everything Judged on Its Own Merit? Object Conservation and the Secular Museum,” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 10, no. 2 (2012): 1–7, http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021203; and Gregory Grieve, “The Rubin Museum of Art: Re-framing Religion for Aesthetic Spirituality,” Journal of Material Religion 3 (2006): 130-135.

- 39My praxis-based research continues to focus on creating sustainable and equitable relationships between museums and members of the transnational Tibetan diaspora. Figure 10 is from a session held at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford in July 2022, during which select Tibetan stakeholders from my doctoral research were invited to participate in discussions at the Pitt Rivers Museum, the British Museum, and the V&A.

- 40According to Laurajane Smith, heritage becomes “a discourse about and through which identity claims are re/created and legitimised – it is not a static process but one in which identity is continually remade and expressed to meet the current and changing needs of individual, community or nation”. Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (Routledge, 2006), 302.

- 41See, for example, Ann McMullen, “The Currency of Consultation and Collaboration,” Museum Anthropology Review 2, no. 2 (2008): 54–87; Bernadette Lynch, “Collaboration, contestation, and creative conflict: On the efficacy of museum/community partnerships,” in Redefining Museum ethics, ed. J. Marstine (Routledge, 2011), 146–163; and Bryony Onciul, Museums, Heritage and Indigenous Voice: Decolonizing Engagement (Routledge, 2015).

- 42Catherine Massola, “Community Collections: Returning to an (Un)Imagined Future,” Museum Anthropology 46, no. 1 (2023): 59–69, https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12267.