The three short essays that follow were written in response to works composed and performed by Tone Yasunao as part of the program “Tokyo: Experiments in Music and Performance” presented at The Museum of Modern Art’s Celeste Bartos Theater on January 10, 2013.

I. Smooth Event (1962)

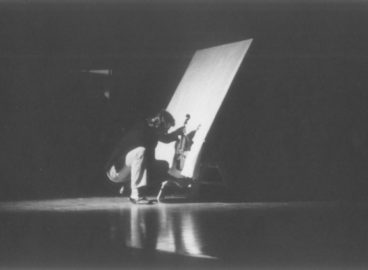

Tone Yasunao walks onstage and approaches a table. He takes off his jacket and hangs it on the wall behind him. He unbuttons his shirt, removes it, flips a switch, and then drapes and buttons the shirt over the body of an electric guitar, which is lying on the table. It is soon evident that the switch has activated the guitar’s amplifier. Tone picks up an iron and proceeds to use the guitar as an ironing board.

Tone’s original event-score for the piece read, simply: “Smooth any form of cloth.” According to that simple instruction, Tone did not have to use an electric guitar as an ironing board, and, indeed, he didn’t have to use an ironing board at all. The only thing needed, Tone has said—although this information is not found in the event-score—is an object capable of making sound.1Dasha Dekleva, “In Parallel,” in Yasunao Tone: Noise, Media, Language, ed. Brandon LaBelle (Los Angeles: Errant Bodies Press, 2007), p. 44.

But in this performance, the sound-making object was a guitar “dressed” in a button-down shirt. Since the event-score called for neither an electric guitar nor a button-down shirt—for the cloth could take any form—then what of this performance?2In each of Tone’s solo performances of Smooth Event, he has utilized an electric guitar and a dress shirt. However, in two early collaborative performances with Kosugi Takehisa, he used other sound-making devices. For the work’s debut in 1962 at Tokyo Gallery, Tone covered Kosugi with a white sheet and smoothed the resulting wrinkles by hand. Another collaborative performance by Tone and Kosugi involved a radio, a dress shirt, Kosugi’s body, a large cloth bag, and an iron. Tone, email correspondence with the author, November 17, 2013.

In Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Green Box) (La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires même [Boîte verte]) of 1934, we find instructions for a never-realized work of art: “Reciprocal Readymade = Use a Rembrandt as an ironing board—.”3Marcel Duchamp, “The Green Box,” trans. George Heard Hamilton, in The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, eds. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (New York: Da Capo, 1973), p. 32. In the original French: “Readymade réciproque = Se servir d’un Rembrandt comme planche à repasser—” Was this a hypothetical artwork, or perhaps a note by the artist to himself to execute the work at a future date—that is, a proto-event-score?

Duchamp’s term “Reciprocal Readymade” implies the reversibility of the readymade concept: the radical act of transvaluing an everyday object into a work of art holds within it its logical opposite, the de-reification of the autonomous work of art by giving it some unforeseen use. However, the simple binary logic that subtends the “reciprocity” of Duchamp’s proposition suggests that the work of art is distinguished from all other objects through the infusion of an abstract and disembodied surplus value. Though the proposition is parodic in tone, Duchamp’s “Reciprocal Readymade” also suggests a utopian position opened up by the liberating act of refusing the system of values upon which high art rests.

The artists associated with Fluxus and with the Happenings of the 1960s did not retain Duchamp’s opposition of art and everyday life. Instead, they sought to dissolve those categories by blurring the boundaries between them, countering the reification of the art object with the dynamic character of the event.4See, for example, Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993). But the category of high art has proved resistant to the refusal of its premises, and in many cases, these post-Duchampian practices have been institutionalized as art.5See Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

In Tone’s performance of Smooth Event, an electric guitar takes the place of Duchamp’s hypothetical Rembrandt painting. Looking back to 1962, we can imagine an “innocent” Smooth Event, in which the terms of music as such were countered by the event. Tone’s future colleagues in Fluxus were using event-scores to this effect at that very moment. But in Tone’s performance on the stage of the Celeste Bartos Theater at MoMA, the amplified sounds emanating from the speakers, and the ambient sounds of the mostly quiet theater itself, met my own ears as manifestly musical. Beyond the staging of Smooth Event on a stage in a museum-sponsored event subtitled “Experiments in Music and Performance,” after Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music (1968) and Sonic Youth, could the humming of the amplified pickups on Tone’s guitar-cum-ironing board sound anything but musical?

Inherent in the body of Tone’s guitar is a capacity to make music, even as he proposed it to be an ironing board. One wonders whether Tone could have foreseen in 1962 the ease with which art would eventually assimilate anti-art strategies, but more than fifty years later, his canniness is beyond question. Rather than accept Duchamp’s opposition of art and the everyday, Tone explores the process by which an object passes between these categories.

Tone first heard about Fluxus events from Ichiyanagi Toshi:

Ichiyanagi told me, “In the U.S. there are guys who do nothing but events.” I thought, “Doing only events sounds all very well, but seeing as how I’ve been doing music thus far, I’d like to compose music and then place it within the context of the event.”6Miki Kaneda, “The ‘John Cage Shock’ is a Fiction! Interview with Yasunao Tone, pt. 1,” in post: Notes on Modern & Contemporary Art Around the Globe (March 8, 2013). http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/178-the-john-cage-shock-is-a-fiction-interview-with-tone-yasunao-1

In Smooth Event, we rarely hear the guitar strings vibrate, but we often hear percussive sounds ringing through the body of the guitar. When Tone flips the instrument in order to iron the back of his shirt, or when the iron strikes the guitar’s body, it is audibly clear that the shirt covers a sonorous object. That this sonorous object is a surrogate for the human body is also clear: the body of the guitar becomes an ironing board; utilized as such, the instrument’s rigid surface substitutes for Tone’s supple body; and, indeed, the flat “board” serves as an ideal, planar body. What we hear issues from the guitar’s own body, a vessel through which sound travels and reverberates. Far from canceling the guitar’s function as a musical instrument, Smooth Event foregrounds the guitar-as-instrument-as-sonic tool.

In 2005 Tone stated of Smooth Event that the instruction to wrap cloth around “anything [that] is able to make sound” leaves open the possibility for “even an instrumental player” to fill the role of the sound-making object.7Dekleva, p. 44. In Smooth Event, when an object is substituted for a human body, a metonymic displacement occurs whereby the reverberation of sound through the body of a guitar is experienced as a substitute for the physical experience of sound by (and through) the listener’s own body. Furthermore, the everyday action of ironing a shirt is not meant to serve as an example of an everyday listening practice: listeners are not urged to go home and pay close attention to the sounds of their own ironing. Rather, a process of identification takes place as the listener projects his or her own body onto Tone’s performing body, and then onto the guitar-as-ironing board, which is clothed in Tone’s shirt and, therefore, acts as a surrogate for his body. This projection is constitutive of music as a performance-based art: the listener conventionally identifies with the performer’s interpretations of musical works, usually mediated by written scores.

Within the program’s theatrical setting, the listener experiences a sense of music-listening-as-disembodiment. The so-called autonomy of concert music arises from a tradition of aesthetic experience that abstracts what the ear hears from the plenitude of the full human sensorium; consequently, listening has become a specialized aesthetic activity abstracted from the soundscape of everyday life. Performed onstage in a museum, Smooth Event reminds us that anti-art’s promise to pass the aesthetic from art to life can always be recuperated as art.

In invoking Duchamp’s own invocation of the Rembrandt easel painting, Tone proposes the history of modern art as a series of passages between mediums and categories of experience that have entailed surrogacies of the body. In doing so, he also reveals a limit in the promise of the everyday that subtended Fluxus events. The everyday calls out to a body, not just to a pair of newly opened eyes or ears. This is why Tone could not foresake music when Ichiyanagi first told him about Fluxus events. It had to be through the very structure of musical experience and its staging in performance contexts that the experience of the everyday could be imagined.

II. Music for a Painting (1962)

Tone Yasunao’s Music for a Painting featured a painting wrapped in butcher paper.8Music for a Painting is alternately titled Music for Every Painting in the World and Music for Every Tableaux. Tone, along with four guest musicians and the program’s two organizers, took turns holding musical instruments in front of the wrapped painting while other participants used scissors to cut out the silhouettes of the shadows cast on the paper by the instruments.

Tone’s instructions, or event-score, for the 1962 piece read:

Cover the surface of tableaux (one or more), with a sheet of white paper. Performer(s) (one or more), may take any instrument, tear white paper once, but area of what one tears must not amount to the area of the instrument’s surface. Performance continues until the sheets are torn up.

What ensued was a provocation of the audience’s viewing of the painting. At the beginning of the performance, when bits of brightly colored, seemingly abstract and brushy swirls of paint came into view, those present could be heard murmuring speculations on the authorship of the still mostly obscured painting. Hans Hofmann? Willem de Kooning? William Baziotes? Early Jackson Pollock? These artists are, of course, pillars of the American modernism famously represented in The Museum of Modern Art’s collection. The performers waited until most of the paper had been cut away before casting a shadow on the lower right-hand corner—the place where the artist’s signature and sometimes a date are usually inscribed—heightening the audience’s desire not only to view the work in its entirety but also to identify it.

Bit by bit, more of the painting was revealed: on the far right, a recognizable shape appeared that turned out to be the depiction of a bone. Well, strike an Ab-Ex artist off the list of possible attributions. Later, an interstitial cut left the paper covering the bottom right corner of the picture dangling, partially obscuring the figure of a camel and the area where a signature was presumed to be hidden. Tone pulled the dangling flap back into place and held it there. Most of the paper had been removed by the time the bottom right corner of the picture was finally revealed (the iron from Smooth Event was used to cut away this crucial portion). There was no signature. I was later told that the painting was made by three of Tone’s guest musicians: Matthew Mottel, Kevin Shea, and Sam Kulik.

In this iteration of Music for a Painting, the “making”—that is, revealing—of the painting by the performers both directs the audience’s perception of the work and also mimics the part-by-part examination of the image that viewers might be expected to conduct upon first encounter with a particular painting. Here, there is an obvious disjunction between the visual life of the painting and its circulation (both the visual circulation of the painting as a displayed image slowly “revealed” to us and its physical circulation as figured by the butcher paper, which would protect its surface during transit between sites of exhibition and exchange), and the event character of the performance as a sonic phenomenon.

The audience’s expectations and anticipation, along with its incredulity at the apparent riskiness of the proceedings—MoMA wouldn’t really let these performers use scissors so close to the surface of an Abstract Expressionist painting, right?—places it in a social relationship with what is happening onstage.9Yoko Ono’s later Cut Piece (1964) is perhaps the most obvious reference point here, but Cut Piece and Music for a Painting share a common antecedent: Tanaka Atsuko’s performance Stage Clothes (1956–57), in which Tanaka strips off layers of costume until she is left wearing nothing but a black leotard and tights. Analyzing the work in relation to Tanaka’s 1955 triptych Work: Yellow Cloth, which consisted of three lengths of unstretched, store-bought cloth, Ming Tiampo describes Stage Clothes as a performance in which “the artist’s body became the ‘canvas’ and the site of visual production.” Ming Tiampo, “Electrifying Painting,” in Electrifying Art: Atsuko Tanaka 1954–1968 (Vancouver and New York: Belkin Art Gallery and Grey Art Gallery, 2004), p. 71. However, the musicality of the “cut” that we hear in the performance suggests that the event is about more than the visual manipulation of desire, that it proposes something beyond directing the eye, which, in its effort to identify the image, exchanges the sensation of viewing the painting for the knowledge gained by reading the artist’s signature.

One of the consequences of—and perhaps the reason behind—the ascendancy of the transportable easel painting was to effect a splitting of the painting as image from the painting as object. This, too, is an operation of exchange. In Music for a Painting, our visual and aural experiences are motivated by the painted image, but Tone adds to this motivation the physical bodies of the instruments, in the same way that he used the body of the guitar in Smooth Event for the extra-musical purpose of ironing. We might think of Music for a Painting as mobilizing tracings of the physical contours of musical instruments to problematize the abstraction of the image from the physical “body” of the painting. Furthermore, in incorporating the protecting wrapping of the painting, the work might also shine a light on the production of this abstraction by the transportability of conventional easel painting. And while it may be too simplistic to posit the aural experience here as merely a figure for that which exceeds the visual—as a figure for the embodiment of the audience and, therefore, as the ungraspable referent of scopic desire—these examples of Tone’s work from the early 1960s presage the anti-exchange impulses in his digital works from the 1980s to the present.

III. MP3 Deviation (Improvisation with Sam Kulik, Matthew Mottel, Lary 7, and Kevin Shea, 2013)

In collaboration with four experimental New York musicians, Tone performed an improvisational version of his most recent project, MP3 Deviation (released on LP, compact disc, and MP3 by the Austrian label Mego). This project involves the corruption of MP3 data while the file is decoded during playback.10A more technologically precise description of the project reads: “a Max/MSP external was written to read an MP3 file into a buffer, decode it as a stream (using the MAD library) frame by frame, and output the resulting audio. Data corruption was applied by sporadically offsetting individual bytes. This was done before decoding, such that the decoder’s attempts to play the corrupted data would be heard.” Thom Blake, et al., “Yasunao Tone and MP3 Deviation,” in International Computer Music Conference Proceedings (2010), pp. 235–236. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/p/pod/dod-idx/yasunao-tone-and-mp3-deviation.pdf?c=icmc;idno=bbp2372.2010.046

In the early sixties Tone participated in musical experiments presented by Group Ongaku at the Sogetsu Art Center. Described by Tone as musique concrète combined with Surrealist automatism, these improvisations with everyday objects serving as musical instruments aimed to pursue a reciprocity between listening experience and improvised musical performance.11See Tone Yasunao, “On Improvised Music as Automatism” (1960), trans. Colin Smith, in post: Notes on Modern & Contemporary Art Around the Globe (February 15, 2013). http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/94-on-improvised-music-as-automatism By the late 1970s, Tone, working as a solo artist and composer, began to investigate the commingling of artistic media and visual and aural sensory experience. For his 1976 performance Voice and Phenomenon at New York’s Experimental Intermedia Foundation, he presented slides in which written characters from eighth-century Chinese poems had been superimposed on photographic images corresponding to those characters’ origins in pictographs.

In 1985 he performed Music for 2 CD Players, in which he manipulated the playing surfaces of compact discs and presented the reading of those altered discs’ digital information as a musical work. The first recorded version of Tone’s “prepared” CDs was Solo for Wounded CD (1997), in which he recorded a “prepared” version of his earlier CD Musica Iconologos (1993). Musica Iconologos was itself an intermedial project. Beginning with two poems from the Classic of Poetry (Shijing, 詩經), the earliest known anthology of Chinese poetry and purportedly compiled by Confucius, Tone substituted found images corresponding to the pictographic origins of the poems’ characters, and then scanned those images digitally. The musical work was Tone’s conversion of the binary code of those scanned images into sound files.

Tone’s technological collaborators at the Music Research Center at the University of York, in England, described the MP3 Deviation project as a “transfer [of] the Wounded CD concept to the MP3 format using data corruption in software.”12Blake, et al., p. 235. The character of this “transfer” from one technological medium to another echoes the commingling of media in Voice and Phenomenon, but here we have not only several media in play but also a collaboration between artist and technician and, metonymically, between artist and technological media. From Music for 2 CD Players to the MP3 Deviations, Tone engages in a reckoning with the digital: by introducing (or foregrounding) error, he destabilizes the digital metanarrative that promises the seamless transfer of information and culture across disparate technological platforms. This is particularly clear as it pertains to the MP3 medium, whose encoding process and technical raison d’être are based on the deletion of digital information for the file’s ease of transfer and storage.

We see in the MP3 Deviations a type of intermedial exchange that began not with the itinerancy of the digital or the coining and first theorization of the term “intermedia” by Tone’s Fluxus colleague Dick Higgins in 1966, but rather with the origins of art itself. Classical Chinese painting of the sort seen on scrolls and album leaves was characterized as manifesting the “three perfections” (sanjue, 三絶): painting, poetry, and calligraphy. Prior to becoming “autonomous” in the centuries after they were anthologized in the first century, the poems that Tone used as source material for his Musica Iconologos were accompanied by music and dance when they were recited.13My thanks to Yu-Chieh Li for pointing out that some literary scholars believe the original Classic of Poetry anthology may have included scores for music and dance and that these were dropped from later versions of the volume.

Of course, ancient Chinese poems cannot be considered autonomous in the modernist sense that Tone himself has characterized as “a purification of genres—namely the separation of individual genres through sensory purification,” and, while he is a committed student of classical Chinese poetry and calligraphy, Tone is not seeking to retrieve from modernism a lost, integrated art.14Yasunao Tone, “A Tectonic Shift in Art: From the Expo to the Hippie Movement” (1967), trans. Christopher Stephens, in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan, 1945–1989, ed. Doryun Chong, et al. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), p. 243. But classical Chinese poetry and painting, especially in the hanging and hand scrolls of the late Song dynasty, display a promiscuous commingling of media that can be posited neither teleologically nor according to a lapsarian narrative. Tone describes the intermedia moment of the 1960s and early seventies as a “tectonic shift,” which can be thought of as an aimless shifting of ground—one that he explicitly poses as a-teleological.

The meta-interface of the digital, in which information exists as infinitely circulating binary code, purports to integrate culture totally. By foregrounding the distressing of the sound file during the conversion of more robust sound recordings into the MP3 format, Tone reinvigorates digital culture with the promise of intermedia that he encountered in the 1960s.

Tone characterized the random alterations to the prepared or “wounded” CD as the results of a process of “decontrolling” the telos of a given medium.15See Roc Jiménez de Cisneros, “Blackout Representation, Transformation and Decontrol in the Sound Work of Yasunao Tone,” in Quaderns d’Àudio 01 (March 29, 2009), p. 10, www.rwm.macba.cat/en/quaderns-audio/qa_yasunao_tone/capsula; and Christian Marclay and Yasunao Tone, “Record, CD, Analog, Digital,” in Audio Culture, eds. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner (New York: Continuum, 2010), p. 344. The instability and neo-Cagean chance operation of digital playback error in Music for 2 CD Players and the MP3 Deviations can be seen as analogous to the open character of the Fluxus event-score. On the event-score, Liz Kotz writes: “. . . the relationship between a notational system and a realization is not one of representation or reproduction but of specification: the template, the schema, or score is usually not considered the locus of the ‘work,’ but merely a tool to produce it; and while the ‘work’ must conform to certain specifications and configurations, its production necessarily differs in each realization.”16Liz Kotz, “Language Between Performance and Photography,” in October 111 (Winter, 2005), pp. 14–15. This openness to chance, which is at the very heart of Fluxus production, underpins all of Tone’s work from the 1960s to the present. Fluxus principles also lie behind Tone’s suspicion toward the musical score as information to be coalesced in performance, and toward the digital sound file as encoded binary information to be coalesced by audio playback software.

In Smooth Event, the guitar’s body is revealed to be a sonorous object. The figuring of the guitar as a surrogate body is repeated in Music for a Painting, in which the physical painting is presented as a clothed body to be disrobed and visually objectified. The painting’s “clothing” here also metonymically refers to its circulation—as a disembodied image—between sites. The ultimate immateriality—or perhaps, again, disembodiment—of the digital file is reembodied in the MP3 Deviations; the usually inaudible compression of the sound file is altered so that it can be heard. Combining the MP3 Deviation with improvised live music at this performance reveals the decontrolled MP3 medium to be aloof from the telos of both technological media and music in the traditional sense.

The musicians in the MP3 Deviation improvisation seem to emit aimless signals, a-rhythmic despite the free-jazz drumming that might have sounded like Rashied Ali if any of the other players had been playing with him in the conventional sense. Instead, they adopted the practice of Group Ongaku, recalled here by Tone: “We made a conscious decision that each member would produce his or her own sound without being affected by the surrounding sounds. That is, each of us listens to the others, but we don’t react to each other directly. If you react, then the music becomes indistinguishable from jazz.”17Kaneda, “Interview with Yasunao Tone.”

At the center of the a-musical improvisation of MP3 Deviation is Tone’s concern not with signals themselves but with the media through which they travel. The format of the MP3 file as an immaterial container for information is given bodily form. What we hear in the piece is the irrationality of the network, removed from the motivations of its functionality and re-motivated by an a-poetic form in which language is senselessly converted into image and finally into sound.

Tone has criticized Marshall McLuhan’s theorization (in The Gutenberg Galaxy) of movable type as a meta-interface. He himself describes the afterlife of the printing press as an abstract detachment of culture “not only from language but from anything that cannot be changed into movable type.”18Tone, “A Tectonic Shift in Art,” p. 243. If the telos of the digital is one of intermedial circulation, then another sense of “intermedia” is employed by Tone to recover the promiscuity behind the exquisite tectonic collisions of media—and, subtending them, the bodily sensations of music and dance subtracted from calligraphic poetry—that produced China’s most famous paintings. Or, rather, Tone resists the technical telos of the MP3’s sound conversion but retains the arbitrariness of the digital collectivization of cultural forms under the master interface of code. In doing so, he has also recovered in imperfect form the intertwining of classical Chinese painting’s three perfections.

In 1967 Tone imagined what he called an “intermediate space,” which we might think of as a phenomenological counter-figure to the disembodying digital void that we once called the “Netscape”: “The word ‘intermedia,’ meaning the space where two mediums intersect, has nothing to do with the problem of an already realized art but instead with its foundation—our own bodies and perceptions.”19Ibid., p. 242.

- 1Dasha Dekleva, “In Parallel,” in Yasunao Tone: Noise, Media, Language, ed. Brandon LaBelle (Los Angeles: Errant Bodies Press, 2007), p. 44.

- 2In each of Tone’s solo performances of Smooth Event, he has utilized an electric guitar and a dress shirt. However, in two early collaborative performances with Kosugi Takehisa, he used other sound-making devices. For the work’s debut in 1962 at Tokyo Gallery, Tone covered Kosugi with a white sheet and smoothed the resulting wrinkles by hand. Another collaborative performance by Tone and Kosugi involved a radio, a dress shirt, Kosugi’s body, a large cloth bag, and an iron. Tone, email correspondence with the author, November 17, 2013.

- 3Marcel Duchamp, “The Green Box,” trans. George Heard Hamilton, in The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, eds. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson (New York: Da Capo, 1973), p. 32. In the original French: “Readymade réciproque = Se servir d’un Rembrandt comme planche à repasser—”

- 4See, for example, Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life, ed. Jeff Kelley (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993).

- 5See Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

- 6Miki Kaneda, “The ‘John Cage Shock’ is a Fiction! Interview with Yasunao Tone, pt. 1,” in post: Notes on Modern & Contemporary Art Around the Globe (March 8, 2013). http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/178-the-john-cage-shock-is-a-fiction-interview-with-tone-yasunao-1

- 7Dekleva, p. 44.

- 8Music for a Painting is alternately titled Music for Every Painting in the World and Music for Every Tableaux.

- 9Yoko Ono’s later Cut Piece (1964) is perhaps the most obvious reference point here, but Cut Piece and Music for a Painting share a common antecedent: Tanaka Atsuko’s performance Stage Clothes (1956–57), in which Tanaka strips off layers of costume until she is left wearing nothing but a black leotard and tights. Analyzing the work in relation to Tanaka’s 1955 triptych Work: Yellow Cloth, which consisted of three lengths of unstretched, store-bought cloth, Ming Tiampo describes Stage Clothes as a performance in which “the artist’s body became the ‘canvas’ and the site of visual production.” Ming Tiampo, “Electrifying Painting,” in Electrifying Art: Atsuko Tanaka 1954–1968 (Vancouver and New York: Belkin Art Gallery and Grey Art Gallery, 2004), p. 71.

- 10A more technologically precise description of the project reads: “a Max/MSP external was written to read an MP3 file into a buffer, decode it as a stream (using the MAD library) frame by frame, and output the resulting audio. Data corruption was applied by sporadically offsetting individual bytes. This was done before decoding, such that the decoder’s attempts to play the corrupted data would be heard.” Thom Blake, et al., “Yasunao Tone and MP3 Deviation,” in International Computer Music Conference Proceedings (2010), pp. 235–236. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/p/pod/dod-idx/yasunao-tone-and-mp3-deviation.pdf?c=icmc;idno=bbp2372.2010.046

- 11See Tone Yasunao, “On Improvised Music as Automatism” (1960), trans. Colin Smith, in post: Notes on Modern & Contemporary Art Around the Globe (February 15, 2013). http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/94-on-improvised-music-as-automatism

- 12Blake, et al., p. 235.

- 13My thanks to Yu-Chieh Li for pointing out that some literary scholars believe the original Classic of Poetry anthology may have included scores for music and dance and that these were dropped from later versions of the volume.

- 14Yasunao Tone, “A Tectonic Shift in Art: From the Expo to the Hippie Movement” (1967), trans. Christopher Stephens, in From Postwar to Postmodern: Art in Japan, 1945–1989, ed. Doryun Chong, et al. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), p. 243.

- 15See Roc Jiménez de Cisneros, “Blackout Representation, Transformation and Decontrol in the Sound Work of Yasunao Tone,” in Quaderns d’Àudio 01 (March 29, 2009), p. 10, www.rwm.macba.cat/en/quaderns-audio/qa_yasunao_tone/capsula; and Christian Marclay and Yasunao Tone, “Record, CD, Analog, Digital,” in Audio Culture, eds. Christoph Cox and Daniel Warner (New York: Continuum, 2010), p. 344.

- 16Liz Kotz, “Language Between Performance and Photography,” in October 111 (Winter, 2005), pp. 14–15.

- 17Kaneda, “Interview with Yasunao Tone.”

- 18Tone, “A Tectonic Shift in Art,” p. 243.

- 19Ibid., p. 242.