Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães recounts Modernist painter Joaquín Torres-García’s years in New York, the strong influence of the metropolis on the development of his style, and his connections and successes in the American art scene in this biographical essay. First part of two.

Each era has its own art. All of the classics have been contemporary in their era—have reflected the life of their era—have been men of their era. We too must be men—like them—of the present—of our era.

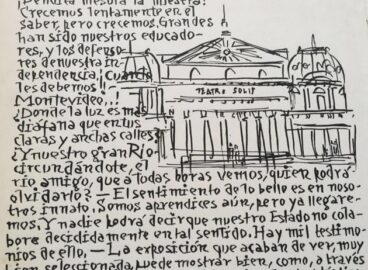

—Joaquín Torres-García, New York. Impresiones de un artista, 19211Joaquín Torres-García, New York. Impresiones de un artista, 1921, in J. Torres–García: New York (Montevideo: Museo Torres García and Casa Editorial HUM, 2007), p. 101. Torres-García wrote the manuscript primarily in New York in 1921–22; a final entry was made in 1930 in Paris. Unpublished at the time, the book later appeared in this facsimile edition, with an introduction by Juan Fló.

On June 16, 1920, Joaquín Torres-García arrived in New York with his wife, Manolita, and their three young children, Olimpia, Augusto, and Ifigenia, ages five through nine (his fourth and last child, Horacio, would be born two years later in Italy). Since 1892, Torres-García had been living in Barcelona, but had grown disillusioned with local politics after government officials forced him to abandon a prestigious commission of large frescoes that he had been working on since 1913 at the Saló Sant Jordi, in the city’s Palau de la Generalitat.2See Exposición de los bocetos y dibujos de los frescos del Salón de San Jorge en la Diputación de Barcelona (Montevideo: Fundación Torres-García, 1974). So he left for New York, telling one of his closest friends, the Uruguayan painter Rafael Barradas, that he intended to work there on manufacturing wooden toys.3Torres-García, letter to Rafael Barradas, May 3, 1919, Barcelona, in Pilar García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas. Un diálogo escrito: 1918–1928 (Barcelona: Parsifal Ediciones, 2001), p. 165. But toy-making gave way to grander ambitions: in New York, Torres-García sharpened his skills as an abstract painter, even while he continued to use the cityscape as his main subject matter, a theme he had begun to explore in Barcelona in 1918. During the two years he lived in the city, he dedicated works to it, met leaders of the American avant-garde, showed in significant galleries, sold work to important collectors, and wrote about his experience in a manuscript he titled New York.4New York. Impresiones de un artista. For more on this book, see, for example, Sergio Chejfec, “Torres-García’s Other Workshop,” in the present volume. His stay in the city began with enthusiastic optimism and a sense of purpose, motivating him to paint everything he saw.

In a letter to Barradas written in early 1920, before he left for the United States, Torres-García imagined New York as a giant, vibrant, dynamic city and proclaimed North America his country.5Torres-García, letter to Barradas, n.d. [February 1920], Barcelona, in García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas, p. 200. A little later, writing from Bilbao, he told Barradas that he felt similarly in this city where everything he saw, “boats, things, railways, trams, cars, cranes, factories, etc.,” fused together to depict a new pictorial vocabulary “like in our paintings.”6Torres-García, letter to Barradas, March 2, 1920, Bilbao, in ibid., p. 205. Barradas, like Torres-García a Uruguayan living in Europe, was influenced by the Cubists and the Futurists and developed a style he called vibracionismo (vibrationism), producing colorful, energetic, and fragmented compositions with an intense rhythm and sense of movement. Torres-García’s paintings of modern Spanish cities showed some of Barradas’s vibracionismo style and had an indirect Cubist inclination.7Torres-García, letter to Barradas, February 25, 1919, Madrid, in ibid., p. 155.

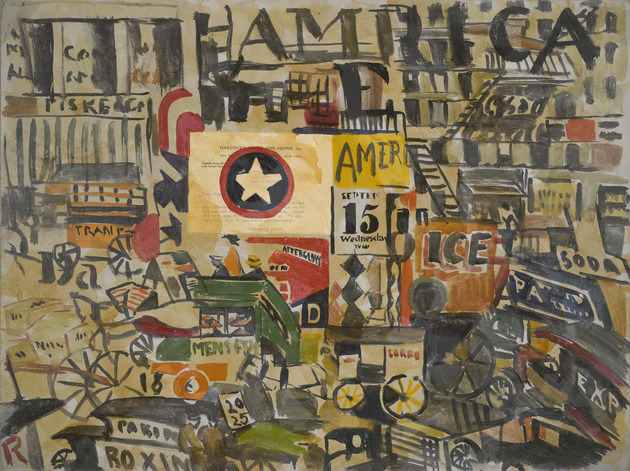

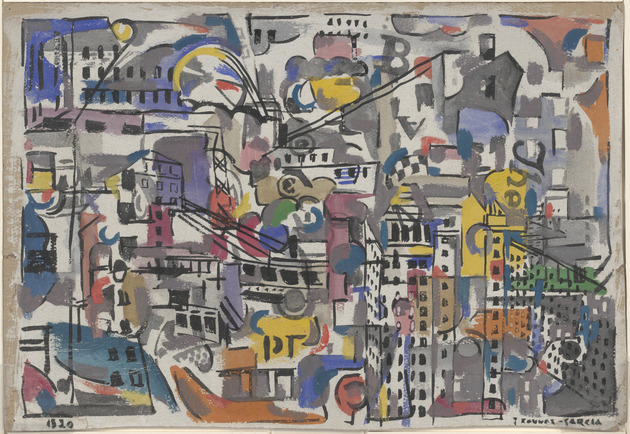

City life, industrialism, and commerce dominate Torres-García’s first New York paintings of 1920. He described these works to Barradas as “synthetic impressions of a distorted New York,”8Torres-García, letter to Barradas, January 31, 1921, New York, in ibid., p. 219. and later, in his autobiography, Historia de mi vida, of 1939 (in which he wrote of himself in the third person), he wrote that they “correspond to a very personal vision, absolutely his, expressionistic and geometric at the same time, and very dynamic.”9Torres-García, Historia de mi vida (Montevideo: Asociación de Arte Constructivo, 1939), p. 214. New York City: Bird’s Eye View (1920), for example, depicts a chaotic city through multiple perspectives, overlapping planes, vibrant colors, and imagery of a young, modern America: skyscrapers, bridges, steamships. Before the end of 1920, Torres-García had produced two sketchbooks of nearly 200 watercolors, numbering them consecutively and stenciling each page with the label “New York” or “N.Y.”10On Torres-García’s New York sketchbooks see Cecilia de Torres, “Torres-García’s New York: The City as Icon of Modern Art,” in Deborah Cullen, ed., Nexus New York: Latin American Artists in the Modern Metropolis (New York: El Museo del Barrio, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2009) These sketchbooks, which have yet to be studied in depth, provide an intimate look at his reaction to the city, in this respect resembling the sketches and studies of American counterparts such as Stuart Davis, John Marin, and Joseph Stella.

Torres-García was not the only immigrant artist to embrace the jolt of energy in American life; in the 1910s, and particularly after the outbreak of World War I had led to a wave of departures from Europe, the “vibrant electricity” and “vital force” of New York mesmerized many French expatriates, including Jean Crotti, Marcel Duchamp, Albert Gleizes, and Francis Picabia.11“French Artists Spur on American Art,” New York Tribune, October 24, 1915, sec. 4, p. 2. One of the city’s reporters called this migration a “French invasion . . . of the young and rebellious in the art of Europe.”12Ibid. Duchamp urged his compatriots to let go of the “Old World” and accept America as “the country of the art of the future.”13Marcel Duchamp, quoted in “The Nude-Descending-a-Staircase Man Surveys Us,” New York Tribune, September 12, 1915, sec. 4 Gleizes spoke of America as a “calm and ordered” place where the “individual counts” and “art is possible”; he was inspired by the movement and stimulation he experienced in the streets.14Albert Gleizes, quoted in “French Artists Spur on American Art,” sec. 4, p. 2. Picabia had felt the same kind of sensation when he came to America in 1913, declaring New York a “cubist, futurist city” because it expressed life, spirit, and modern thought through its architecture, skyscrapers, and subways.15Francis Picabia, “How New York Looks to Me,” New York American, March 30, 1913, p. 11.

Torres-García’s expressive metropolitan imagery evidently appealed to Katherine Dreier, an active collector and impresario of modern art under the name of the Société Anonyme, which she had cofounded with Duchamp and Man Ray. In his autobiography Torres-García writes of a visit from Dreier to his studio at 4 West 29th Street, leading to her purchase of three works for the Société: New York Docks (1920), New York City: Bird’s Eye View, and New York Street Scene (1920).16The date of Katherine Dreier’s visit is unknown, but must have occurred between September 1920 and January 1921. Torres-García wrote in his autobiography that he had moved to his studio at 4 West 29th Street on August 28, 1920, and says that Dreier’s visit to him came after he had begun to paint more regularly in his new location. Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 198. On January 31, 1921, he wrote to Barradas that he had sold his first New York views, referring to Dreier’s purchase. See García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas, p. 219. (She made another purchase in 1929, when Torres-García was living in Paris and invited her to visit his studio there;17Torres-García, letter to Dreier, Paris, April 15, 1928. Katherine S. Dreier Papers/Société Anonyme Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. the visit led to her acquisition of a 1929 work called Docks, and the artist also gave her a suite of six watercolors, Artists’ Ball, that he had made in New York in 1921.) New York Street Scene, in oil and collage on board, depicts a frenzied city street densely packed with motor vehicles. Advertising signage scattered across the composition evokes the commercial market’s permeation of public space. Above and to the right, before a facade of tenementlike buildings, Torres-García paints the word “America” in capital letters, the letter “e” wedged below the letters “m” and “r.” Right below it is a collage element, a fragment of a letter dated August 6, 1920, from the publishing house Harcourt, Brace and Howe, Inc., rejecting the artist for a job. Emboldened by this refusal, Torres-García pastes the letter on the composition’s surface, paints a patriotic star over it, and partly frames it with a deconstructed American flag. The superimposition of the letter over images of America’s booming industrial and commercial economy points to the incongruity between the country’s promises and the reality of his own situation.18On employment rejections Torres-García experienced in New York, see Historia de mi vida, pp. 190–91, 194, 198–201, 212.

Torres-García’s brief connection to the Société Anonyme and the artists involved with it had a significant impact on his artistic maturity. Founded at 19 East 47th Street, New York, in 1920, the same year he arrived in the city, the Société established itself as an educational organization designed “for the promotion of the study in America of the Progressive in Art, based on Fundamental Principles, and to render aid in conserving the vigor and vitality of new expressions of beauty in the Art of today.”19“The Exhibition of the Collection of the Société Anonyme–Museum of Modern Art: 1920,” in Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University X, no. III (December 1941):1. The Société organized exhibitions, publications, and educational programming to promote modern artists such as Duchamp, Stella, Man Ray, Marsden Hartley, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, and John Storrs. Between 1920 and its closure in 1950, it produced eighty exhibitions, eighty-five educational public programs, and nearly thirty publications, and it amassed a collection of over 1,000 works, now at the Yale University Art Gallery.20See Jennifer R. Gross, “An Artist’s Museum,” in Gross, The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with the Yale University Art Gallery, 2006), p. 2.

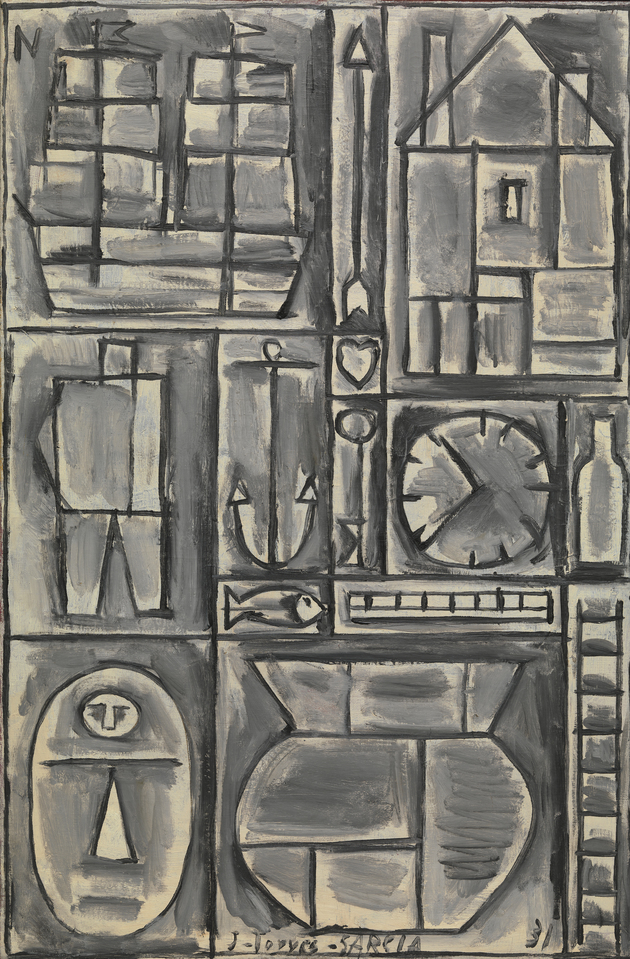

Although Torres-García’s contact with Dreier was limited, and the works of his that she purchased were never exhibited during his lifetime (New York Docks was shown in 1952, New York City: Bird’s Eye View and New York Street Scene not until 1971), she recognized his contribution to the evolving language of modern painting.21New York Docks was exhibited in Space in Painting at the University of Minneapolis, January 28–March 7, 1952; New York City: Bird’s Eye View and New York Street Scene were included in the Torres-García retrospective organized by Barbara Duncan at the University Museum, University of Texas at Austin, December 1971–January 1972. In 1949, in one of many drafts she wrote for a catalogue of the Société’s collection, she called him one of “those artists who have a passion for Art. . . . For him it took many forms. . . . He was a deeply rooted individualist, creating his personal statements, which gave him a strong independent position in the art world.” She went on to describe his works in the collection as “very individual in expression. . . . only those who have a keen eye for the construction and division of space . . . can realize his achievement.”22Dreier, draft catalogue entry, 1949. YCAL MSS 101, box 34, folder 1001, in the Katherine S. Dreier Papers/Société Anonyme Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. See also Dreier’s final entry in “Catalogue,” Collection of the Societé Anonyme: Museum of Modern Art 1920 (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, published for the Association in Fine Arts, 1950), pp. 55–56. Torres-García’s New York experience helped him to establish the structural matrix of his constructivist compositions of the 1930s, mainly by revealing the grid structuring the city’s monumental frontality and balancing its vertical and horizontal elements, creating the “division of space” that Dreier mentioned. In New York (1921), for example, he uses the geometric configuration of a building facade and an adjoining elevated rail- or roadway to establish a compartmentalized overall composition. This kind of complex construction of forms reappears in Composition (1931), where the composition is divided into geometric shapes and rectangular substructures housing Torres-García’s recurring symbols for man, space, time, and other concepts indexed in his works by figures, clocks, rulers, stars, and cardinal points, for example.

In addition to Dreier, Torres-García made a number of connections in New York that fostered friendships and established him in the city’s art scene. Through the Catalan architect and urban planner Cebriá de Montoliu, for example, who had emigrated to New York in early 1920, he met Walter Pach, an artist, critic, and advisor who had worked closely with artists Arthur B. Davies and Walt Kuhn in the organization of what has come to be called the Armory Show—the International Exhibition of Modern Art, held at the Sixty-ninth Regiment Armory in 1913.23See Cecilia de Torres, “Torres-García’s New York,” pp. 106, 122 n. 10. Pach offered Torres-García room and board in a building at 13 East 14th Street for a couple of months before the artist and his family relocated to 4 West 29th Street. Pach also introduced Torres-García to possible sources of employment and to artists such as John Xceron, who in turn introduced him to Stella and Max Weber. It was at Stella’s studio that Torres-García met “the Whitney ladies”—Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who would found the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1931, and her assistant Juliana R. Force, the museum’s first director.24Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 208.

In 1918, at 147 West 4th Street in Greenwich Village, Whitney had created an exhibition space called the Whitney Studio Club where she promoted the works of avant-garde and American artists. Here, in the spring of 1921, she offered Torres-García an exhibition, to be shared with Davis and Stanislaw Szukalski.25See the exhibition advertisements in The Arts, April 1921, section VII, and American Art News 19, no. 29 (April 30, 1921):3. The exhibition was planned to run from April 25 through May 16, 1921, but was extended through May 26. (Torres-García would also exhibit in the Club’s Annual Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture in April of the following year.) The exhibition was warmly reviewed in the New York Times as “perhaps one of the most interesting, certainly the most unusual, exhibitions that has been in the gallery this year.”26“Art: Exhibitions and Paintings,” New York Times, May 1, 1921, p. 85. (Exhibitions earlier in the year had included etchings and drawings by Charles Frederick William Mielatz and James Donald Corley and decorative textiles and figurative sculptures by Salvatore Bilotti, Harold Perry Erskine, and Gerome Brush.)27Hamilton Easter Field, “Comments on the Arts,” The Arts, February–March 1921, p. 50. Although the show was shared with Davis and Szukalski, it was Torres-García who received the most attention from the press. Critic Hamilton Easter Field described him as “closer to the reality of things, closer to life, closer to himself [than the other two]. His talent is more vital. His paintings of life in our modern cities are admirable in their compactness.”28Field, “Art Exhibitions and Artists,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 1, 1921, p. 39. For another review of the exhibition see “New Art at Whitney Studio Club,” American Art News 19, no. 29

Torres-García had come to New York with a great deal of his earlier work in his luggage (he wrote about doing the same thing when traveling from Barcelona to Madrid in 1919), allowing him to include works from previous years in the Whitney Studio Club exhibition and others.29Torres-García, letter to Barradas, October 10, 1919, Barcelona, in García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas, p. 177. For a list of works in the Whitney Studio Club show see An Exhibition of Paintings by Stuart Davis and J. Torres-Garcia and Sculptures by Stanislaw Szukalski_, exh. brochure (New York: The Whitney Studio Club, 1921), available online under “additional material/links” in Cecilia de Torres’s Torres-García catalogue raisonné, at http://torresgarcia.com/exhibitions/entry.php?id=532 (accessed July 9, 2015). Among the earliest works shown at the Studio Club, from c. 1908, was El ensanche de Barcelona (Suburbio de Barcelona) (The expansion of Barcelona [Suburb of Barcelona]), an image of Barcelona as a city on the brink of expansion into a modern metropolis. He exhibited this painting with later works such as Calle de Nueva York (New York street, 1920), which depicts the city as a single urban conglomerate of buildings, transportation, and signage. In incorporating his new pictorial language, works like these illustrate the evolution of Torres-García’s style.

At the same time that Torres-García was showing at the Whitney Studio Club he was participating in Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings Showing Later Tendencies in Art, a group exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, from April 16 through May 15.30For a list of the artists and their works, see Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings Showing Later Tendencies in Art, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1921). This catalogue is available online under “additional material/links” in Cecilia de Torres’s Torres-García catalogue raisonné, at http://torresgarcia.com/exhibitions/entry.php?id=580 (accessed July 17, 2015). In the course of one year, then, Torres-García had participated in two prominent exhibitions in the United States. The Philadelphia show featured artists Arthur Dove, Marius de Zayas, Hartley, Man Ray, Stella, Weber, and others, and was applauded as a great success—“in every way the best show of modern American art ever held,” according to Field, who again noted Torres-García among those artists he saw as “exceptional.”31Field, “Comments on the Arts,” The Arts, May 1921, pp. 34–35. The show included Torres-García’s painting Fourteenth Street (Business Town) (1920), which shows the lively intersection of 14th Street and Fifth Avenue, a few doors away from where he and his family had spent the summer of their arrival.

Torres-García was also connected to the Society of Independent Artists, a New York–based group of Americans and Europeans who supported annual exhibitions of contemporary art. Founded in 1916 by Dreier, Duchamp, Gleizes, Marin, Pach, Man Ray, Stella, Walter Arensberg, and John Sloan, the society followed the model of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in Paris, established in 1884, and like its French counterpart it staged “equal-opportunity” annual exhibitions in which artists of all schools could exhibit together independent of jury decisions and prizes.32Exhibition leaflet of the Society of Independent Artists, 1917. Miscellaneous art exhibition catalog collection, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Like Dreier and Whitney, Arensberg and his wife, Louise, were important American collectors and patrons of modern art. In 1950 they would donate their remarkable collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Their home, at 33 West 67th Street, was a hub for artists and intellectuals; among their frequent guests were Duchamp, Picabia, Crotti, Gleizes, Sheeler, Stella, the poet William Carlos Williams, and the artist and art dealer de Zayas.33See Barbara Haskell, The American Century: Art & Culture, 1900–1950 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1999), p. 108.

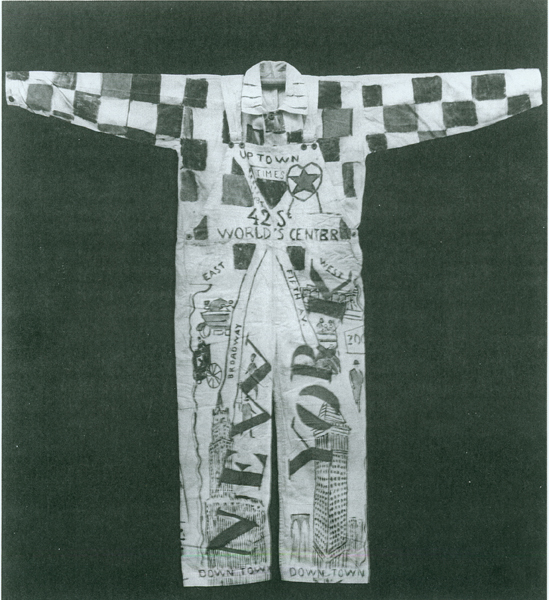

Torres-García participated in the society’s fifth annual exhibition, which was installed at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel from February 26 through March 24, 1921, and was, according to one critic at the time, “quite the best the Independents had given.”34Field, “Comments on the Arts,” The Arts, February–March 1921, p. 50. For the exhibition’s dates see “Exhibition Calendar,” The Arts, January 1921, p. 59, and “The Art Calendar,” The Arts, February–March 1921, p. 62. He also attended a costume ball that the society staged at the hotel during the show’s run. For this event Torres-García wore a garment of his own design: canvas overalls painted to depict New York City. On the front of the two pant legs he drew the words “New” and “York.” The upper half of the costume contained the words “Uptown,” “Times Square,” and “World Trade Center” amid a pulsating check pattern (he also wore a checkered long-sleeved shirt); the lower half represented the East Side and the West Side of Manhattan, with Broadway and Fifth Avenue as the city’s main arteries, and each leg was emblazoned with a skyscraper, the Woolworth and Banker’s Trust buildings. On the back of the costume were written “Central Park” and “Bronx Zoo,” and below them “Bowery” and “Wall Street”; at the very bottom was a depiction of the Brooklyn Bridge and a ferry.35See de Torres, “Torres-García’s New York,” p. 114. The costume further elaborated Torres-García’s appropriation of the urban motif. Rather than simply depicting New York, he was New York, embedding the city’s fundamental structures in his clothing and body: uptown, downtown, east, west, his limbs dividing the architectural space that would come into play in his later work.

A New York Times reporter called the ball “pretty,” given the “prismatic colors” of most of the costumes and the predominance of the color yellow in both costumes and décor.36“Greenwich Village Tops Artists’ Ball,” New York Times, March 12, 1921, p. 11. Specifically mentioning Torres-García, Xceron, and Stella, the article praised the men as more adventurous than the women: “The New York Times Building found itself unexpectedly dancing with the Independents on the costume of J. Torres Garcia [sic], the Spanish artist, who had New York City outlined on his costume. . . . John Xeron [sic], Greek futurist artist, was in a futuristically painted costume with a tall futuristic hat; Joseph Stella, who painted Brooklyn Bridge—in a picture—not the bridge itself—in a Spanish mantle as an Emperor ‘with a kingdom’ he insisted.”37Ibid. Torres-García did not lose the opportunity to sketch at the ball, producing fast mini-portraits of Xceron, Stella, and others. In spirit these sketches echo his Artists’ Ball watercolors of the same year, which he would make a gift of to Dreier in Paris in 1929. Whether those watercolors refer to the Society of Independent Artists ball at the Waldorf or to other social gatherings that he attended in New York, they supply anecdotal observations of his convivial, active social life in the city.

This is the first section of the essay. Read Part 2 here. Excerpted from Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães’ essay “Spirit of America: Joaquín Torres-García in New York, 1920-1922” in the exhibition catalog Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern available at the MoMA Design Store.

- 1Joaquín Torres-García, New York. Impresiones de un artista, 1921, in J. Torres–García: New York (Montevideo: Museo Torres García and Casa Editorial HUM, 2007), p. 101. Torres-García wrote the manuscript primarily in New York in 1921–22; a final entry was made in 1930 in Paris. Unpublished at the time, the book later appeared in this facsimile edition, with an introduction by Juan Fló.

- 2See Exposición de los bocetos y dibujos de los frescos del Salón de San Jorge en la Diputación de Barcelona (Montevideo: Fundación Torres-García, 1974).

- 3Torres-García, letter to Rafael Barradas, May 3, 1919, Barcelona, in Pilar García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas. Un diálogo escrito: 1918–1928 (Barcelona: Parsifal Ediciones, 2001), p. 165.

- 4New York. Impresiones de un artista. For more on this book, see, for example, Sergio Chejfec, “Torres-García’s Other Workshop,” in the present volume.

- 5Torres-García, letter to Barradas, n.d. [February 1920], Barcelona, in García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas, p. 200.

- 6Torres-García, letter to Barradas, March 2, 1920, Bilbao, in ibid., p. 205.

- 7Torres-García, letter to Barradas, February 25, 1919, Madrid, in ibid., p. 155.

- 8Torres-García, letter to Barradas, January 31, 1921, New York, in ibid., p. 219.

- 9Torres-García, Historia de mi vida (Montevideo: Asociación de Arte Constructivo, 1939), p. 214.

- 10On Torres-García’s New York sketchbooks see Cecilia de Torres, “Torres-García’s New York: The City as Icon of Modern Art,” in Deborah Cullen, ed., Nexus New York: Latin American Artists in the Modern Metropolis (New York: El Museo del Barrio, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2009)

- 11“French Artists Spur on American Art,” New York Tribune, October 24, 1915, sec. 4, p. 2.

- 12Ibid.

- 13Marcel Duchamp, quoted in “The Nude-Descending-a-Staircase Man Surveys Us,” New York Tribune, September 12, 1915, sec. 4

- 14Albert Gleizes, quoted in “French Artists Spur on American Art,” sec. 4, p. 2.

- 15Francis Picabia, “How New York Looks to Me,” New York American, March 30, 1913, p. 11.

- 16The date of Katherine Dreier’s visit is unknown, but must have occurred between September 1920 and January 1921. Torres-García wrote in his autobiography that he had moved to his studio at 4 West 29th Street on August 28, 1920, and says that Dreier’s visit to him came after he had begun to paint more regularly in his new location. Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 198. On January 31, 1921, he wrote to Barradas that he had sold his first New York views, referring to Dreier’s purchase. See García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas, p. 219.

- 17Torres-García, letter to Dreier, Paris, April 15, 1928. Katherine S. Dreier Papers/Société Anonyme Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- 18On employment rejections Torres-García experienced in New York, see Historia de mi vida, pp. 190–91, 194, 198–201, 212.

- 19“The Exhibition of the Collection of the Société Anonyme–Museum of Modern Art: 1920,” in Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University X, no. III (December 1941):1.

- 20See Jennifer R. Gross, “An Artist’s Museum,” in Gross, The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with the Yale University Art Gallery, 2006), p. 2.

- 21New York Docks was exhibited in Space in Painting at the University of Minneapolis, January 28–March 7, 1952; New York City: Bird’s Eye View and New York Street Scene were included in the Torres-García retrospective organized by Barbara Duncan at the University Museum, University of Texas at Austin, December 1971–January 1972.

- 22Dreier, draft catalogue entry, 1949. YCAL MSS 101, box 34, folder 1001, in the Katherine S. Dreier Papers/Société Anonyme Archive, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. See also Dreier’s final entry in “Catalogue,” Collection of the Societé Anonyme: Museum of Modern Art 1920 (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, published for the Association in Fine Arts, 1950), pp. 55–56.

- 23See Cecilia de Torres, “Torres-García’s New York,” pp. 106, 122 n. 10.

- 24Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 208.

- 25See the exhibition advertisements in The Arts, April 1921, section VII, and American Art News 19, no. 29 (April 30, 1921):3. The exhibition was planned to run from April 25 through May 16, 1921, but was extended through May 26.

- 26“Art: Exhibitions and Paintings,” New York Times, May 1, 1921, p. 85.

- 27Hamilton Easter Field, “Comments on the Arts,” The Arts, February–March 1921, p. 50.

- 28Field, “Art Exhibitions and Artists,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 1, 1921, p. 39. For another review of the exhibition see “New Art at Whitney Studio Club,” American Art News 19, no. 29

- 29Torres-García, letter to Barradas, October 10, 1919, Barcelona, in García-Sedas, ed., Joaquín Torres-García y Rafael Barradas, p. 177. For a list of works in the Whitney Studio Club show see An Exhibition of Paintings by Stuart Davis and J. Torres-Garcia and Sculptures by Stanislaw Szukalski_, exh. brochure (New York: The Whitney Studio Club, 1921), available online under “additional material/links” in Cecilia de Torres’s Torres-García catalogue raisonné, at http://torresgarcia.com/exhibitions/entry.php?id=532 (accessed July 9, 2015).

- 30For a list of the artists and their works, see Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings Showing Later Tendencies in Art, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1921). This catalogue is available online under “additional material/links” in Cecilia de Torres’s Torres-García catalogue raisonné, at http://torresgarcia.com/exhibitions/entry.php?id=580 (accessed July 17, 2015).

- 31Field, “Comments on the Arts,” The Arts, May 1921, pp. 34–35.

- 32Exhibition leaflet of the Society of Independent Artists, 1917. Miscellaneous art exhibition catalog collection, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- 33See Barbara Haskell, The American Century: Art & Culture, 1900–1950 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1999), p. 108.

- 34Field, “Comments on the Arts,” The Arts, February–March 1921, p. 50. For the exhibition’s dates see “Exhibition Calendar,” The Arts, January 1921, p. 59, and “The Art Calendar,” The Arts, February–March 1921, p. 62.

- 35See de Torres, “Torres-García’s New York,” p. 114.

- 36“Greenwich Village Tops Artists’ Ball,” New York Times, March 12, 1921, p. 11.

- 37Ibid.