Aleksandar Bošković traces the Hollywood references and self-referential play in filmmaker Slobodan Šijan’s paracinematic Film Leaflet. The full set of Leaflets was recently acquired by The Museum of Modern Art Library, and is now available to researchers.

Slobodan Šijan’s single-page, double-sided fanzine Film Leaflet (Filmski letak), created and distributed monthly from 1976 to 1979, is an example of a paracinema form that transcends the habitual understanding of what constitutes a film. It is an amalgamation of fan writing, drawings, photography, critical analysis of films and filmmakers, appropriated newspaper clippings, cine-poetry, storyboards, postcards, and the like. Compiled with a do-it-yourself aesthetic, Šijan’s fanzine was conceived as a project of serial “paper movies,” as Branko Vučičević, an influential film critic and scriptwriter, terms such combinations of text and image, and which film scholar Pavle Levi calls “cinema by other means.”1Branko Vučičević, Paper Movies: poučne priče (Belgrade: B92; Zagreb: Arkzin, 1998), 20-21; Pavle Levi, Cinema by Other Means (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 28-29.

Although conceived and printed in the late 1970s, Film Leaflet both reflects and embodies Šijan’s decade-long experience of living as an emerging artist in the increasingly Westernized cultural milieu of socialist Yugoslavia. Šijan, who graduated from the Fine Arts Academy in Belgrade, enrolled in Belgrade’s Academy of Theater, Film, Radio, and Television in 1970 to study with Živojin Pavlović, a well-known Black Wave film director. In 1972, Šijan witnessed the reactionary reversal of the political climate of the film school triggered by the controversy surrounding Lazar Stojanović’s Plastic Jesus (Plastični Isus, 1971), and he graduated several years after the witch-hunt at the school had subsided, when artistic freedoms among filmmakers were drastically curtailed.2Šijan describes this state of affairs in his book Filmski letak: 1976–1979 (i komentari) = Film Leaflet(s): 1976– 1979 (with comments): “The purges at the Film School continued with undiminished intensity until Aleksandar Petrović was fired and Živojin Pavlović transferred to the post of teaching aides custodian. [. . .] The witch-hunt expanded beyond the School, forcing Dušan Makavejev to leave the country. Lazar Stojanović was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison, which he served almost in full, for a graduation film that was never publicly shown.” Slobodan Šijan, Filmski letak: 1976–1979 (i komentari) = Film Leaflet(s): 1976–1979 (with comments)(Belgrade: Službeni glasnik, 2009), 150. Šijan’s art practice was inspired by diverse cultural phenomena, including the 1960s counterculture and psychedelic art, the idea of the “junkyard” promoted by Leonid Šejka (an established visual artist, writer, and founder of the Mediala group in Belgrade), and both American underground and Hollywood films. But Šijan was even more influenced by his close friendship with Tomislav Gotovac and the experimentation with time-based arts—photography/slides, video, film, and performance. These practices developed within the conceptual paradigm of experimental art, established within the framework of the Yugoslav New Art Practice of the 1960s and 1970s and promoted around the youth and student cultural centers in Novi Sad, Zagreb, Ljubljana, and Belgrade.3Ješa Denegri, “Art in the Past Decade,” in The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia, 1966–1978, ed. Marijan Susovski (Zagreb: Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1978), 11. http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2011/ScenesFromZagreb/.

Šijan started Film Leaflet in 1976—“out of frustration”4Šijan, Filmski letak: 1976–1979 (i komentari) = Film Leaflet(s): 1976–1979 (with comments) (Belgrade: Službeni glasnik, 2009), 7.—as an intermediary step between his work with experimental films (from 1970 to 1976, he directed and assisted in the making of about twenty experimental and short films) and his first TV films, while trying to break into professional Yugoslav cinema. He began his fanzine as a way to continue his painterly practice after he had stopped making paintings and drawings and started making Xerox copies of his graphic works. In the foreword of his 2009 book, he wrote: “Film Leaflet is a sort of ‘fanzine’ or ‘do-it- yourself’ newsletter, halfway between poor graphic and samizdat, created with the idea of making, once a month, a visual and textual statement about film, or related to film (conceived in the broadest possible sense). It was printed using whatever technology was available to me, on one A4 sheet, and distributed to friends and other people interested in film.”5Ibid. The print run of the original leaflets was very small, ranging from 50 to 250 copies.

Film Leaflet can be understood as a ciné-dispositive, that is, an “instrument” for thinking about cinema as well as a real, concrete, experiential form of the Yugoslav 1970s ciné-apparatus.6Taking my cue from Françis Albéra and Maria Tortajada’s discussion of dispositif, I follow Ruggero Eugeni’s definitions of dispositive and apparatus as two different and connected concepts to which the French termdispositif refers. Thus, an apparatus is “a network of discourses, pieces of knowledge, values, etc., reciprocally linked and governed/defined by strategies of management of power,” while a dispositive is the “mechanism of a device, instrument or machine” that allows spectators to attend a representation. See Ruggero Eugeni, “Dispositif, Apparatus, Dispositive,” https://prezi.com/2rn4eww1nhcu/dispositif-apparatus-dispositive/; Françis Albéra and Maria Tortajada, Cine-Dispositives (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2015), 21. Conceptualized as a platform for the free use of film history, mass media, and pop culture in critical practice, Šijan’s ciné-dispositive exercised direct appropriation—re-signification, recombination, and reproduction—of diverse contents across media in order to articulate a “new language” of film thought along with a practice of critical inquiry into cultural reproduction. As a concrete paracinema form of the Yugoslav ciné-apparatus, Šijan’s fanzine was one of the key alternative forms for expressing the ideological symptoms and processes of cultural reproduction within 1970s Yugoslavia. As such, Film Leaflet both reflected upon and embodied the contradictions of the socialist and capitalist cultural hybridization specific to the Yugoslav experience at the time.

Despite its small scale, the fanzine was ambitious in the range of issues it covered. From the start, it addressed the social potential of cinema as both a countercultural form and a practice promoting the free development of socialist culture. The first three leaflets, for example, propose a critical re-thinking of the history of both experimental and popular cinema in international as well as domestic contexts. Thus, the inaugural leaflet represents a reaction to George Maciunas’s December 1969 Diagram, in which the Fluxus artist offers his own classification of the newest trends in avant-garde cinema. Šijan adds to Maciunas’s classification the most important films made in 1963–64 by structural filmmakers Mihovil Pansini and Tomislav Gotovac, thus enhancing understanding of the Yugoslav “anti-film” movement in the wider context of Western avant-garde cinema. Leaflets 2 and 3 respond to domestic issues and represent Šijan’s reaction to the communist witch- hunt surrounding the Black Wave film movement.

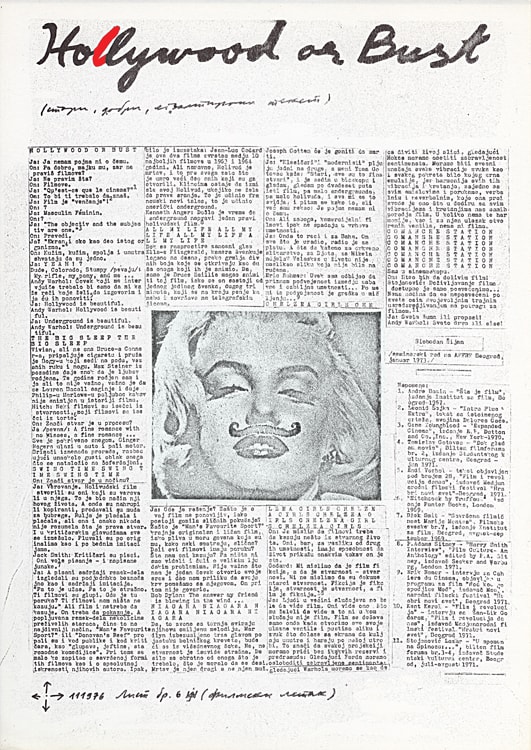

Šijan’s fanzine displays and articulates a transition from understanding cinema as a subversive instrument for social change, characteristic of the Black Wave filmmakers, to seeing it as an instrument for critical inquiry into cultural reproduction. Šijan’s 1973 manifesto “Hollywood or Bust,” printed in 1976 asLeaflet 6, is emphatic in ascribing equal importance to both “experimental” or underground film and “commercial” Hollywood cinema, through an imagined discussion between Šijan and Andy Warhol that includes quotations from Jack Smith.7“Me: Hollywood is beautiful. Andy Warhol: Hollywood is beautiful. Me: Underground is beautiful. Andy Warhol: Underground is beautiful.” At the same time, Šijan quotes the following short comment by Jack Smith, from Smith’s text “The Perfect Film Appositeness of Maria Montez,” published in the journal Film Culture: “Eventually someone is going to make a so-called underground movie that will revive Hollywood.” Šijan, Filmski letak, 2009, 38. Šijan’s professor at the Academy of Theater, Film, Radio, and Television in Belgrade Dušan Stojanovićaccepted this unconventional essay, which would later become a leaflet, as a seminar paper for his course Theory of Film. See Šijan, Filmski letak, 2009, 36. “My taste at that time,” explained Šijan in 2009, “inclined towards extremes like underground and ‘trash.’ I could not stand the middle ground; those films which were here [in Yugoslavia] and all over the world considered great works. I loved esoteric, highly personal experiments or products of mass culture.”8Šijan, Filmski letak, 2009, 7. My translation.

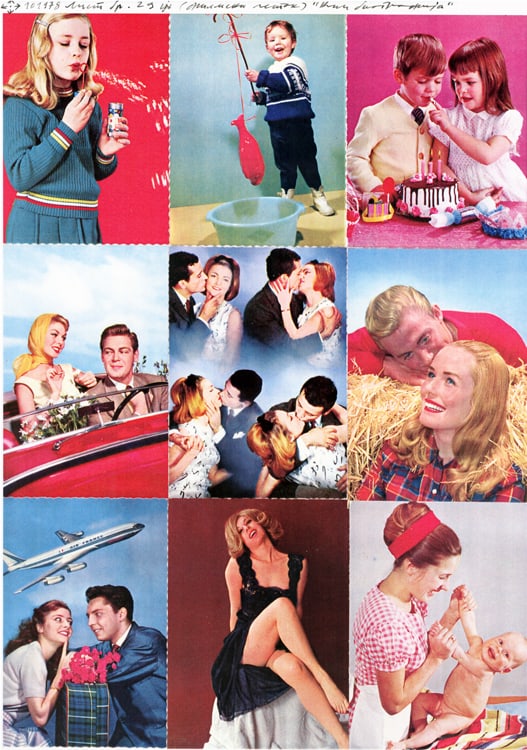

Šijan’s work with a series of kitsch postcards, which has been instrumental in promoting the image of the consumption-centered “good life” in socialist Yugoslavia, perfectly illustrates his peculiar taste at the time. Leaflet 29, titled “Kitsch Biography,” features a straightforward narrative characterized by kitsch’s aesthetic of denial, which transforms disgust into universal approval and thus ignores all that is difficult about life.9The original collage was displayed in a group exhibition of twelve artists in the Happy New Gallery of the Student Cultural Center (SKC) in Belgrade in 1978. Although the gallery planned to print the leaflet in color, they didn’t end up doing so, and it was not until several decades later, in 1999, that Šijan printed fifty copies in color. Šijan experimented with photocopying the original “Technicolor” postcards in order to achieve the same effect as the domestic kitsch quality of Yugoslav pulp magazines, such as in Leaflet 13, in which colorful postcards are given a black-and-white, dirty “underground” quality reminiscent of “trash” or “camp” aesthetics.10Leaflet 13 was printed in the inaugural issue of the journal The Look (Izgled, June 1977), with a print run of 600 copies.

Šijan came out against the uncritical appropriation of Western commodity fetishism and its aesthetics of denial in an ostensibly socialist society, juxtaposing it—in a number of his leaflets promoting the aesthetics of “trash,” “camp,” and the bizarre —with the cultural reproduction of transgressive enjoyment in the media consumption of socially abject phenomena (pornography, disease, madness). For example, Leaflet 17 features an unintentionally campy story published in the first Serbian erotic magazine, Adam and Eve; Leaflet 22 simply reproduces without alteration a newspaper article on a disease whose name is pronounced just likeŠijan’s own; Leaflet 23 presents Šijan’s handwritten copy of the letter that the Serbian modernist painter Sava Šumanović wrote in a deranged state of mind to his close friend, the avant-garde poet Rastko Petrović; and Leaflet 27 presents verbatim the court appeal of Nguen Van Ter, a thirty-five-year-old construction worker, originally published in Playboy magazine and republished in an issue of the Yugoslav magazine Izbor.

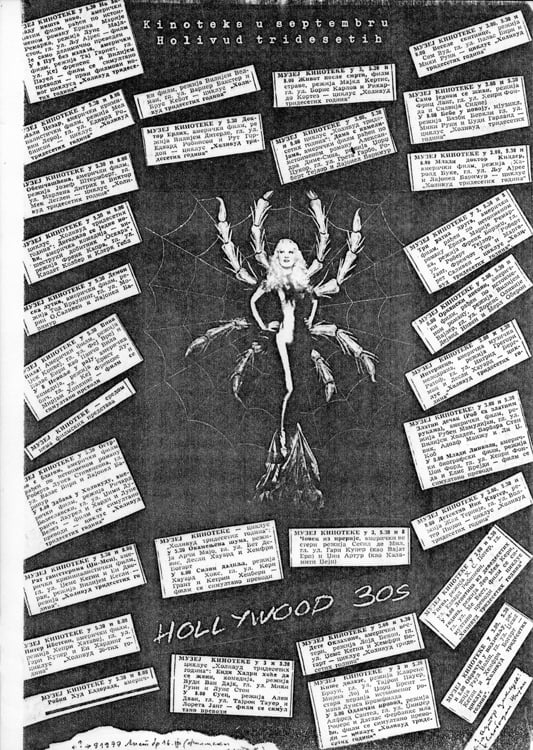

It is hard to overestimate the roles of cinephilia and Americanophilia in Šijan’s thinking about cinema.11Šijan found a guide for his exploration of American cinema and practice of cinema-going in an important figure in the early interwar Yugoslav ciné-apparatus, Boško Tokin, coauthor of “The Zenithist Manifesto” (1921). Tokin was one of the first Yugoslav cinephiles to write about American film in the 1920s. Leaflet 5 features several of Tokin’s cine-poems, accompanied by a short, handwritten note from Šijan on his work, acknowledging the latter’s unsuccessful co-directorial venture with the Yugoslav Dadaist Dragan Aleksić, their unfinished and lost 1924 avant-garde film. A number of Film Leaflets make unambiguous statements about the importance of American cinema for Šijan and subsequent generations of Yugoslav moviegoers. Leaflet 9 features the famous list drawn up by the French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville, which served as a guide for Šijan through the jungle of American cinema. Šijan organized a retrospective at Yugoslav Cinematheque featuring a number of titles from the list. He reproduced the program of the retrospective as Leaflet 16, titled “Hollywood 30s,” with Mae West in the center of the leaflet as she appears in a scene from Leo McCarey’s film Belle of the Nineties(1934). In a similar gesture of appreciation for American film, Leaflet 21 praises the “new sentimentality” of New American Cinema, providing a list of relevant American films made between 1967 and 1977, starting with Bonnie and Clyde(Arthur Penn, 1967).12Penn’s film was the most watched film in Yugoslavia in 1968; it influenced different aspects of everyday life and popular culture there. See Radina Vučetić, Coca-Cola Socialism: Americanization of Yugoslav Culture in the Sixties (Budapest-New York: Central European University Press, 2018), 55-56.

Šijan went on promoting American commercial cinema out of his belief that significant ideas are often born in the domain of popular culture. Hence the three leaflets endorsing American B movies: Leaflet 10 featuring Šijan’s essay on the filmVanishing Point (1971), published in the brochure for the retrospective of director Richard Sarafian that Šijan organized at the SKC Belgrade in March 1977; Leaflet24 representing Šijan’s essay about the Hollywood film director Richard Fleischer, printed in the brochure for the retrospective of Fleischer’s films at the SKC in April 1978;13See Slobodan Šijan, Richard Fleischer (Belgrade: Izdavačko-informativno-dokumantrani program SKC-a, 1978), 17pp. Slobodan Šijan, “Tačka iščezavanja,” Film, No. 14/15 (Centar za kulturnu djelatnost SSO Zagreb, 1978). and Leaflet 42 promoting Šijan’s unpublished essay about Richard T. Heffron’s film Trackdown (1976), in which Šijan articulates that B movies offer something that Yugoslav socialism suppressed for fear of spreading violence among the youth.

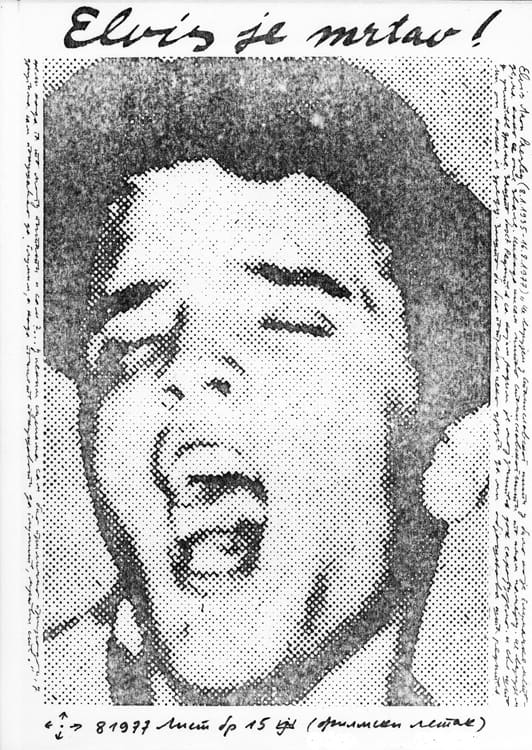

Several leaflets addressed the movie-star phenomenon, starting with Leaflet 15, which was made in response to Elvis Presley’s death in 1977. Featuring a photocopied photo-portrait of the young rock ’n’ roll star with the sensationalistic title “Elvis is Dead!” in bold cursive letters, this leaflet emphasizes the idea of the movie star as a nonprofessional actor in its short, handwritten annotation. As his interest in Elvis demonstrates, Šijan was equally interested in celebrities and nonprofessional actors, paying homage to the latter in Leaflet 25, a collage of the mostly peasant “movie stars” who appeared in Šijan’s feature for television, Most Beautiful Room (Najlepša soba, 1978). This leaflet functions as an ideologically charged counter-narrative to the movie-star phenomenon, since it re-introduces the worker (peasants who move to the city) into the Yugoslav cultural imagination. BothŠijan’s leaflet and his TV film show that the worker was able to recuperate his lost symbolic currency in the everyday imaginary of socialist Yugoslavia only as an ideal figure of the new commercial cultural industry, as a “movie star” (a singer or a fashion model being other options)—no longer “the hero of production,” but instead “the hero of consumption.” Infatuation with movie stars prompted Šijan to make a piece as a teenager in 1960, which he later published as Leaflet 40, ironically commenting on his initial enchantment with movie stars. On this leaflet featuring a postcard with a glamour shot of Tony Curtis, Šijan replaced the actor’s name with his own, the gesture re-signifying the simple postcard of a movie star as a conceptual artwork.

On the other hand, the November and December issues of Film Leaflet were conceived as “official selections of film festivals” and awards to the experimental film authors or journals participating in the “competition.” At the end of 1976, Šijan came up with the idea that the December issue for each year would present a Top 10 list of the best foreign films shown in Yugoslav movie theaters. The list would also include the best films in the domestic cinema and, more importantly, announce that year’s Yugoslav winner of the Film Leaflet award. In the period from 1976 to 1979, there were four December issues published and four winners of the “prestigious” award.14In 1976, Ljubomir Šimunić from Belgrade, for his 8mm film rolls (Leaflet 7); in 1977, Tom Gotovac, for his filmGlenn Miller I (High School Playground I) (Leaflet 19); in 1978, the Zagreb magazine Film (Leaflet 31); and in 1979, Branko Vučičević and his screenplay for the feature film Medusa’s Raft, directed by Karpo Godina in 1980 (Leaflet 43). Leaflet 43 was also the last issue of Film Leaflet, which ceased to exist when Šijan’s professional career took off and he could no longer keep up with his fanzine production. At the same time, Šijan proposed that the Film Leaflet award winner would earn the right to publish his/her work in the next year’s November issue of the fanzine. The entire run of Film Leaflet includes only three November issues featuring the work of the awardees.15These are “The Work of Ljubomir Šimunić,” which comprises an advertisement for his imaginary film company “Moon” (Leaflet 18); the work of Tom Gotovac, titled “The Glenn Miller Chesterfield Shows” (Leaflet 30); and the “Zagreb magazine Film” published from 1975 to 1979 (Leaflet 42). The guiding concept behind the November and December issues resembles that of FEST, an annual film festival in Belgrade established in 1971 to assess the films of the previous year. Nonetheless, these issues focus exclusively on the films distributed in cinema theaters and highlight what official awards ignored. With the introduction of the Film Leafletaward, Šijan continued to recognize and promote Yugoslav experimental filmmakers and film critics while mimicking a mainstream practice of the Yugoslavciné-apparatus.

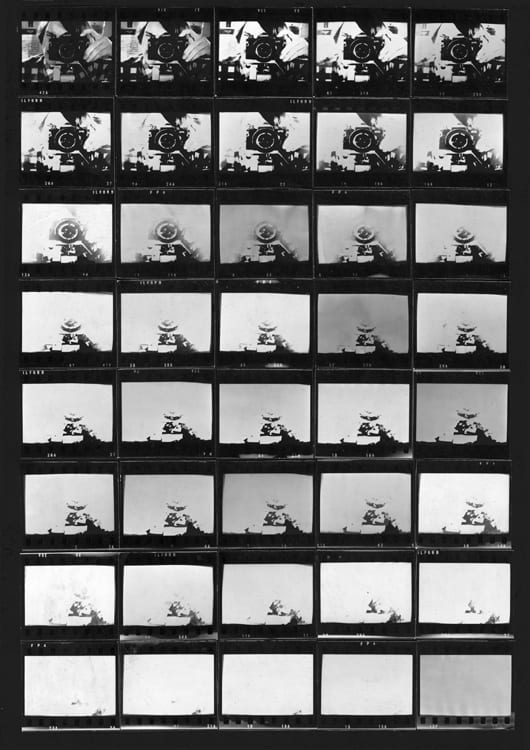

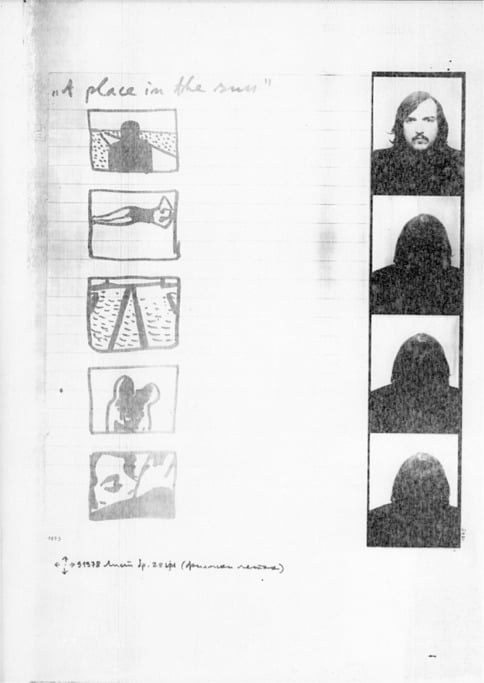

Some issues of Film Leaflet examine the limits of the medium of film, such asLeaflet 4, titled “Project for a Family Film,” and Leaflet 11, titled “Media Suicide: Investigation No. 2, Photography.” Several issues embody the so-called graphic- visual statements about the characteristic rhythms of shot progression in the films of renowned Hollywood directors: John Ford (Leaflet 32), Howard Hawks (Leaflet33), Alfred Hitchcock (Leaflet 34), Vincente Minnelli (Leaflet 35), and Robert Altman (Leaflet 36). Other leaflets were conceived as storyboards (Leaflet 8) or comic strips (Leaflets 12 and 37), while the most radical examples conceptualize the act of watching films as a latent, continuous process of film creation (Leaflets 26 and 28). These examples demonstrate that “the possibility of directly entering the filmic reality,” as Pavle Levi aptly put it in his skillful analysis of Šijan’s Leaflets, is a key concern that has persistently motivated Šijan’s work.16Levi, Cinema by Other Means, 127.

Šijan’s Film Leaflet emerged as a form of “praxis of radical amateurism,” to use Aldo Milohnić’s definition, which established a “new language” of film thought and production outside the dominant models, using the resources within state-funded institutions (Yugoslav Cinematheque, SKC, Studentski Grad Film Club).17Aldo Milohnić, “Radikalni amaterizam,” in Raškolovano znanje//Priručnik (Belgrade: TKH, 2012), 4. Forged in an environment of the hybridization of the arts, within a network in which official and alternative cultures coalesced, and through the practices of cinema-going and programming, Šijan’s ciné-dispositive emerged as a self-referential hypertext of radical amateurism that articulated and performed a critical inquiry into the cultural reproduction within late 1970s Yugoslav socialism.

- 1Branko Vučičević, Paper Movies: poučne priče (Belgrade: B92; Zagreb: Arkzin, 1998), 20-21; Pavle Levi, Cinema by Other Means (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 28-29.

- 2Šijan describes this state of affairs in his book Filmski letak: 1976–1979 (i komentari) = Film Leaflet(s): 1976– 1979 (with comments): “The purges at the Film School continued with undiminished intensity until Aleksandar Petrović was fired and Živojin Pavlović transferred to the post of teaching aides custodian. [. . .] The witch-hunt expanded beyond the School, forcing Dušan Makavejev to leave the country. Lazar Stojanović was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison, which he served almost in full, for a graduation film that was never publicly shown.” Slobodan Šijan, Filmski letak: 1976–1979 (i komentari) = Film Leaflet(s): 1976–1979 (with comments)(Belgrade: Službeni glasnik, 2009), 150.

- 3Ješa Denegri, “Art in the Past Decade,” in The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia, 1966–1978, ed. Marijan Susovski (Zagreb: Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1978), 11. http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2011/ScenesFromZagreb/.

- 4Šijan, Filmski letak: 1976–1979 (i komentari) = Film Leaflet(s): 1976–1979 (with comments) (Belgrade: Službeni glasnik, 2009), 7.

- 5Ibid.

- 6Taking my cue from Françis Albéra and Maria Tortajada’s discussion of dispositif, I follow Ruggero Eugeni’s definitions of dispositive and apparatus as two different and connected concepts to which the French termdispositif refers. Thus, an apparatus is “a network of discourses, pieces of knowledge, values, etc., reciprocally linked and governed/defined by strategies of management of power,” while a dispositive is the “mechanism of a device, instrument or machine” that allows spectators to attend a representation. See Ruggero Eugeni, “Dispositif, Apparatus, Dispositive,” https://prezi.com/2rn4eww1nhcu/dispositif-apparatus-dispositive/; Françis Albéra and Maria Tortajada, Cine-Dispositives (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2015), 21.

- 7“Me: Hollywood is beautiful. Andy Warhol: Hollywood is beautiful. Me: Underground is beautiful. Andy Warhol: Underground is beautiful.” At the same time, Šijan quotes the following short comment by Jack Smith, from Smith’s text “The Perfect Film Appositeness of Maria Montez,” published in the journal Film Culture: “Eventually someone is going to make a so-called underground movie that will revive Hollywood.” Šijan, Filmski letak, 2009, 38. Šijan’s professor at the Academy of Theater, Film, Radio, and Television in Belgrade Dušan Stojanovićaccepted this unconventional essay, which would later become a leaflet, as a seminar paper for his course Theory of Film. See Šijan, Filmski letak, 2009, 36.

- 8Šijan, Filmski letak, 2009, 7. My translation.

- 9The original collage was displayed in a group exhibition of twelve artists in the Happy New Gallery of the Student Cultural Center (SKC) in Belgrade in 1978. Although the gallery planned to print the leaflet in color, they didn’t end up doing so, and it was not until several decades later, in 1999, that Šijan printed fifty copies in color.

- 10Leaflet 13 was printed in the inaugural issue of the journal The Look (Izgled, June 1977), with a print run of 600 copies.

- 11Šijan found a guide for his exploration of American cinema and practice of cinema-going in an important figure in the early interwar Yugoslav ciné-apparatus, Boško Tokin, coauthor of “The Zenithist Manifesto” (1921). Tokin was one of the first Yugoslav cinephiles to write about American film in the 1920s. Leaflet 5 features several of Tokin’s cine-poems, accompanied by a short, handwritten note from Šijan on his work, acknowledging the latter’s unsuccessful co-directorial venture with the Yugoslav Dadaist Dragan Aleksić, their unfinished and lost 1924 avant-garde film.

- 12Penn’s film was the most watched film in Yugoslavia in 1968; it influenced different aspects of everyday life and popular culture there. See Radina Vučetić, Coca-Cola Socialism: Americanization of Yugoslav Culture in the Sixties (Budapest-New York: Central European University Press, 2018), 55-56.

- 13See Slobodan Šijan, Richard Fleischer (Belgrade: Izdavačko-informativno-dokumantrani program SKC-a, 1978), 17pp. Slobodan Šijan, “Tačka iščezavanja,” Film, No. 14/15 (Centar za kulturnu djelatnost SSO Zagreb, 1978).

- 14In 1976, Ljubomir Šimunić from Belgrade, for his 8mm film rolls (Leaflet 7); in 1977, Tom Gotovac, for his filmGlenn Miller I (High School Playground I) (Leaflet 19); in 1978, the Zagreb magazine Film (Leaflet 31); and in 1979, Branko Vučičević and his screenplay for the feature film Medusa’s Raft, directed by Karpo Godina in 1980 (Leaflet 43). Leaflet 43 was also the last issue of Film Leaflet, which ceased to exist when Šijan’s professional career took off and he could no longer keep up with his fanzine production.

- 15These are “The Work of Ljubomir Šimunić,” which comprises an advertisement for his imaginary film company “Moon” (Leaflet 18); the work of Tom Gotovac, titled “The Glenn Miller Chesterfield Shows” (Leaflet 30); and the “Zagreb magazine Film” published from 1975 to 1979 (Leaflet 42).

- 16Levi, Cinema by Other Means, 127.

- 17Aldo Milohnić, “Radikalni amaterizam,” in Raškolovano znanje//Priručnik (Belgrade: TKH, 2012), 4.