Alejandro Paz Navas’s The Bodyguard is a testament to a generation of artists who mobilized conceptual performances in public spaces to respond to the socio-economic changes in postwar Guatemala.

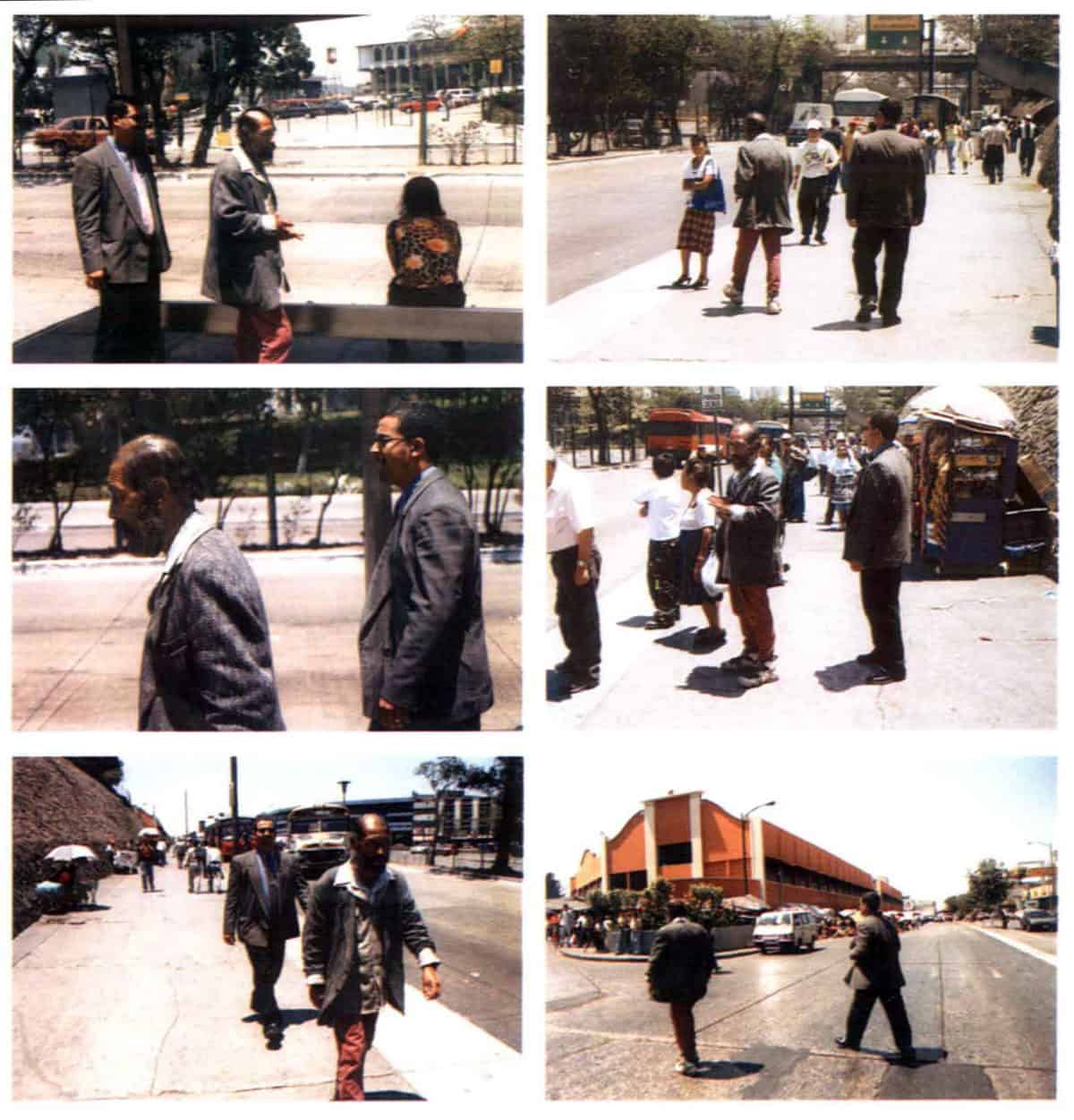

In April 2002, Guatemalan artist Alejandro Paz Navas (born 1975) realized the conceptual project titled The Bodyguard (El Guardaespaldas). This rudimentary video documents almost fifteen minutes of the daylong action that Paz Navas created on the streets of Guatemala City with two borrowed cameras and the help of fellow artist Jorge de León (born 1976). To execute the project, Paz Navas first contracted a professional bodyguard for the day, informing him that he would be asked to perform his usual labor but withholding details about whom he would be guarding. Next, the artist found a beggar willing to participate without pay. Highlighting the conceptual nature of the venture, Paz Navas explains that he did not want to use actors but rather to engage real people who would play the roles they hold in daily life. For this reason, their compensation—or lack thereof—mirrored that of their professions. Throughout the video, the bodyguard escorts the beggar through the Centro Cívico—the Guatemalan government’s center of power—to the peripheries of the city.1The Centro Cívico was primarily constructed during the first years following the coup of 1954 and then under the military dictatorship. It includes the Teatro Nacional designed by Efraín Recinos, the Banco de Guatemala, the Municipal Building, and the Instituto Guatemalteco de Seguridad Social. As a demonstration of Guatemalan culture, some of the country’s most well-known artists at the time, including Roberto González Goyri, Carlos Mérida, Recinos, Dagoberto Vásquez, and Guillermo Grajeda Mena, were brought in to create murals for the exteriors and interiors of the buildings. Carried out entirely in the streets, The Bodyguard provides a point of entry into the dynamics of public space at the turn of the twenty-first century in Guatemala. Building on an analysis of The Bodyguard, this text elucidates how a generation of artists in Guatemala utilized the city to create work that visualizes the traces of the Civil War (1960–96) and its aftermath.

Following thirty-six years of armed conflict, the Guatemalan Civil War came to an end in 1996 with a signed peace agreement. The effects of more than three decades of brutal violence, however, remained present in the lives of individuals and the social fabric of the country. The entry of transnational corporations following the peace accords allowed for the invasion by neoliberal policies and free market economies, which disproportionately benefited the upper class and left the rural and urban poor with lower wages and increasingly fewer employment opportunities. Discussing how this widening economic disparity provoked greater demand for personal protection, Avery Dickins de Girón explains that the 1996 peace accords resulted in a decrease in the police force, while wage inequality led to a rise in urban violence and police corruption. For those with disposable income, private bodyguards became both a safety measure and a sign of status. Dickins de Girón writes: “Walking through any commercial zone in Guatemala City, one is struck by the number of armed guards posted outside supermarkets, delivery trucks, and restaurants. Whether they instill a sense of comfort or fear, the individuals behind the guns—most of them rural peasants—symbolize the unequal social and economic conditions in contemporary Guatemalan society.”2Avery Dickins de Girón, “The Security Guard Industry in Guatemala: Rural Communities and Urban Violence,” in Securing the City: Neoliberalism, Space, and Insecurity in Postwar Guatemala, eds. Kevin Lewis O’Neill and Kedron Thomas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 103. See also Mario Roberto Morales, “Power and Imposition in Guatemalan Contemporary Art,” in Guatemala from 33,000 km: Contemporary Art, 1960–Present, exh. cat. (Santa Barbara, CA: Museum of Contemporary Art, Santa Barbara, 2017), 37. It is important to note that most people seeking employment as bodyguards come from low-income communities and, therefore, despite the difference in how they earn their living, the country’s homeless population and those hired as bodyguards in Guatemala City often have a shared history.

Paz Navas is part of a generation of artists that includes Regina José Galindo (born 1974), Aníbal López (A-1 53167; 1964–2014),3Aníbal López also went by the code name A-1 53167, his ID card number, as a way to prevent ethnic-specific interpretations or attempts to categorize him as indigenous, Mayan, or Guatemalan. Jorge de León, Yasmin Hage (born 1976), and María Adela Díaz (born 1973), who formed their practices in the postwar period. Centering their work on conceptual actions and public performance, they were impacted by the Grupo Imaginaria—especially its members Pablo Swezey (1959–2014) and Luis González Palma (born 1957)—a collective that, founded in 1987 in Antigua, was the first artistic initiative to confront the traumas of the Civil War.4Emiliano Valdés, “Guatemala from 33,000 km,” in Guatemala from 33,000 km, 25. For an analysis of the emergence of contemporary art in Guatemala, see Cecilia Fajardo Hill, “El nacimiento de la vanguardia contemporánea en Guatemala, 1965–1974,” in GT 20/21, eds. Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and José Falconi (forthcoming). Without official institutional art circuits, the postwar artists developed their work parallel to the emergence of the experimental art festival Octubre Azul;5The performance festival Octubre Azul was named for the October Revolution, a movement led by students, teachers, and military reformers that overthrew the thirteen-year dictatorship of Jorge Ubico in October 1944 and ushered in ten years of democratic reforms. The Revolution came to an end in 1954 with the CIA’s first Latin American coup of the Cold War. See Greg Grandin, Deborah T. Levenson, and Elizabeth Oglesby, eds., “Ten Years of Spring and Beyond,” in The Guatemala Reader (Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 197. alternative spaces Proyecto de Artistas Independientes (PAI), Colloquia, and Casa Bizarra; and Espacio Contexto, which, for the first time, brought exhibitions of international contemporary artists such as Santiago Sierra (born 1966) and Teresa Margolles (born 1963) to Guatemala City.6Valdés, “Guatemala from 33,000 km,” 25; Rosina Cazali, “Horror Vacui Vacio Non Plenitud: Primera muestra de performance, acciones e intervenciones artísticas,” in Los Desaparecidos/Horror Vacui (Guatemala: 2008), 15; Alejandro Paz Navas, interview by the author, April 28, 2020. Some of these artists were involved with PAI, including Jorge de León, Regina José Galindo, Aníbal López, José Osorio, and María Adela Díaz; Santiago Sierra and Teresa Margolles each had a solo exhibition at Espacio Contexto in 2000. Due to the lack of established art institutions and financial resources, these young artists often worked in the streets, developing ideas for projects while on the bus, sharing meals, or traversing the city. Describing the environment following the peace accords, Regina José Galindo remembers: “Around 1997, ’98, and ’99, there was a feeling that things were about to change. There was a degree of peace, and at that time, a group of youths took to the streets. We went out onto the streets. And we started to produce art in the public space.”7“Artist Video: Regina José Galindo: La víctima y el victimario,” March 26, 2015, Guggenheim website, https://www.guggenheim.org/video/regina-jose-galindo-la-victima-y-el-victimario-english-captioned.

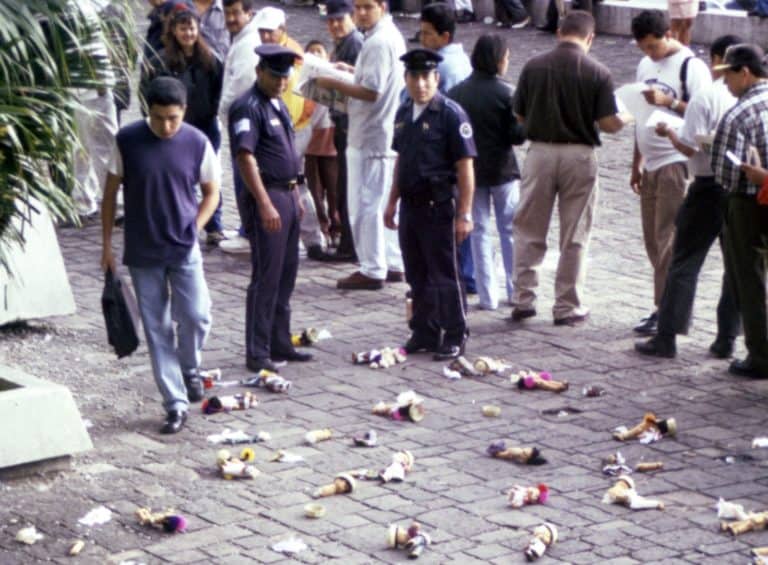

Speaking to neoliberalism’s precarious attitude toward life, Judith Butler suggests: “When bodies assemble in the street, in the square, or in other forms of public space[,] . . . they are exercising a plural and performative right to appear, one that asserts and instates the body in the midst of the political field, and which, in its expressive and signifying function, delivers a bodily demand for a more livable set of economic, social, and political conditions no longer afflicted by induced forms of precarity.”8Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2015), 11. This strategic implementation of the “right to appear” permeates the work of Paz Navas and his generation vis-à-vis their counteraction of the erasure of history and bodies from the realm of the public. For Octubre Azul in 2000, Paz Navas realized the action Genocide (Genocidio), in which he threw approximately one hundred broken dolls into the plaza in front of the Supreme Court and the Tribunal building. On their way to their government jobs, civilians occasionally paused to look, but more commonly walked over the broken toys without paying notice. This work invokes both the violence inflicted on hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans during the Civil War and the willful ignorance that citizens adopted in order to disregard such reality. Staged in front of the city’s court buildings, Genocide also highlights the problem of bringing the perpetrators to justice. Referencing this artwork, Rodolfo Arévalo writes, “Justice, despite its huge building and the investment of different governments and foreign aid, does not operate as expected,” pointing out that in the early 2000s, only about 2 percent of all homicide cases in Guatemala resulted in the incarceration of those guilty.9Rodolfo Arévalo S., “La huella del otro, su sombra: Contribución a un encuentro con E. Lévinas desde el arte de acción,” in Los Desaparecidos/Horror Vacui, 44. “La justicia, pese a su enorme enorme edificio y la inversión de los distintos gobiernos y la ayuda extranjera, no opera como se espera.” Translation by author.

Beyond the financial and institutional realities that propelled these artists into the street, it is also important to note the significance that public access to information held for them. Following the end of the Civil War, a Truth Commission was established to investigate the crimes committed by the military. Horrific details, especially about the genocide of Mayan communities in the countryside, began to emerge. Referring to the impact of these atrocities on his generation, Paz Navas explains: “The war in Guatemala was experienced in a very opaque way. We lived in the city, but it was very difficult to know what was taking place beyond the limits of the city, methods of information and communication were completely controlled by the government’s—the military’s—agenda, and it was not understood what was happening.”10Alejandro Paz Navas, interview with the author, April 28, 2020. “La guerra en Guatemala se vivió en una manera muy opaca. Vivíamos en una ciudad, pero era muy difícil conocer que era lo que estaba sucediendo más allá de los límites de la ciudad, los métodos de información y comunicación estaban totalmente captados por una agenda del gobierno—del ejército—y no se entendía que era lo que estaba sucediendo.” Translation by author. Creating actions in the streets, artists emphasized the need for transparency by making their work completely accessible to the public. The city became a platform on which to visualize previously concealed facts about the armed conflict and its lasting effects on the country and its citizens.

The practice of exposing the indelible traces of violence can be found in the work of many artists of this generation. The same year that Paz Navas executed Genocide, Aníbal López organized an art action titled June 30, 2000, the photographic documentation of which was presented at the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001. In anticipation of a military parade that took place along the Sexta Avenida, López covered the entire route with ashes. An act that subversively and discretely recalled the burned villages and bodies of people massacred during the war, the scattered ashes were mostly removed by the start of the parade. Nevertheless, the remains were smeared along the avenue as the soldiers, some of whom committed genocide during the Civil War, marched in celebration. Also in 2000, María Adela Díaz staged a public intervention titled Allegory of Reality (Alegoría de la Realidad), in which the artist dyed twelve white doves red and released them in Guatemala City’s Parque Central to symbolize the blood of Guatemalans who died every day. In 2003, upon hearing that Efraín Ríos Montt—the dictator from 1982 to 1983 who oversaw a scorched-earth campaign—was running for office again, Regina José Galindo performed Who Can Erase the Traces? (¿Quién puede borrar las huellas?). Walking barefoot from the Constitutional Court toward the National Palace in the Parque Central, she periodically dipped her feet in a basin of blood, which she carried with her, leaving a path of crimson footprints behind her.

Realized on the street, in parks, and plazas, these projects also gesture toward the changing economics of postwar Guatemala. With the increasing violence and poverty brought on by neoliberalism, the privatization of public space as urban renewal projects attempted to turn “undesirable” zones into “dignified” areas filled with shopping, restaurants, and other leisure spaces for the upper class and tourists to enjoy. Theorizing a neoliberal vision of space through these development projects, Rodrigo J. Véliz and Kevin O’Neill argue: “The reality, however, is that not all Guatemalans are free to visit these spaces. Paradoxically, these efforts at urban renewal yield places that are not all that public—places that look inviting but that nevertheless restrict the flow of certain people and certain goods.”11Rodrigo J. Véliz and Kevin O’Neill, “Privatization of Public Space: The Displacement of Street Vendors in Guatemala City,” in Securing the City, 85. In fact, these privatized undertakings forcibly displaced street vendors just like the ones seen toward the end of The Bodyguard. In this sense, it could be that rather than providing the beggar with protection, the bodyguard in Paz Navas’s project enacts a privatized policing of the “undesirable” and “public” Guatemalan subject, defending financial prosperity rather than people. This possibility is highlighted by the fact that we see the bodyguard escorting the beggar who, in search of income, asks unheeding pedestrians for spare change. With this project and others such as Genocide, June 30, 2000, Allegory of Reality, and Who Can Erase the Traces?, these artists of the postwar generation made subtle yet compelling interventions to visualize the impact when the body politic is sacrificed by the state for capital and power, a dehumanizing tactic that traversed life in Guatemala before and after the peace accords.

Working in the streets of Guatemala City, Paz Navas and his generation grappled with the repercussions of the Civil War and the changing dynamics that came with the importation of neoliberal policies. They occupied the spaces being usurped by a narrowing elite to attempt to make unavoidable the socioeconomic realities that many citizens had tried to ignore. At the same time, there was an awareness on their part of the persistence of invisibility even in the public sphere, as demonstrated by the two subjects featured in The Bodyguard. Paz Navas notes that despite their seemingly conflicting professions, the cruel irony is that both are unable to enter the private spaces of the upper classes and both are treated as anonymous citizens by the public. When considered with the previously mentioned knowledge that the bodyguards and the homeless frequently come from similar backgrounds, their shared anonymity further binds them.12Alejandro Paz Navas, interview with the author, April 28, 2020. See also “Alejandro Paz Navas Talks About His Work,” February 9, 2019, Colección Cisneros website, https://coleccioncisneros.org/content/alejandro-paz-navas-talks-about-his-work. In this sense, in The Bodyguard, Paz Navas creates a correspondence between two seemingly distinct beings, both of whom navigate the complex and contradictory postwar landscape that characterized Guatemala City at the turn of the twenty-first century.

- 1The Centro Cívico was primarily constructed during the first years following the coup of 1954 and then under the military dictatorship. It includes the Teatro Nacional designed by Efraín Recinos, the Banco de Guatemala, the Municipal Building, and the Instituto Guatemalteco de Seguridad Social. As a demonstration of Guatemalan culture, some of the country’s most well-known artists at the time, including Roberto González Goyri, Carlos Mérida, Recinos, Dagoberto Vásquez, and Guillermo Grajeda Mena, were brought in to create murals for the exteriors and interiors of the buildings.

- 2Avery Dickins de Girón, “The Security Guard Industry in Guatemala: Rural Communities and Urban Violence,” in Securing the City: Neoliberalism, Space, and Insecurity in Postwar Guatemala, eds. Kevin Lewis O’Neill and Kedron Thomas (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 103. See also Mario Roberto Morales, “Power and Imposition in Guatemalan Contemporary Art,” in Guatemala from 33,000 km: Contemporary Art, 1960–Present, exh. cat. (Santa Barbara, CA: Museum of Contemporary Art, Santa Barbara, 2017), 37.

- 3Aníbal López also went by the code name A-1 53167, his ID card number, as a way to prevent ethnic-specific interpretations or attempts to categorize him as indigenous, Mayan, or Guatemalan.

- 4Emiliano Valdés, “Guatemala from 33,000 km,” in Guatemala from 33,000 km, 25. For an analysis of the emergence of contemporary art in Guatemala, see Cecilia Fajardo Hill, “El nacimiento de la vanguardia contemporánea en Guatemala, 1965–1974,” in GT 20/21, eds. Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and José Falconi (forthcoming).

- 5The performance festival Octubre Azul was named for the October Revolution, a movement led by students, teachers, and military reformers that overthrew the thirteen-year dictatorship of Jorge Ubico in October 1944 and ushered in ten years of democratic reforms. The Revolution came to an end in 1954 with the CIA’s first Latin American coup of the Cold War. See Greg Grandin, Deborah T. Levenson, and Elizabeth Oglesby, eds., “Ten Years of Spring and Beyond,” in The Guatemala Reader (Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 197.

- 6Valdés, “Guatemala from 33,000 km,” 25; Rosina Cazali, “Horror Vacui Vacio Non Plenitud: Primera muestra de performance, acciones e intervenciones artísticas,” in Los Desaparecidos/Horror Vacui (Guatemala: 2008), 15; Alejandro Paz Navas, interview by the author, April 28, 2020. Some of these artists were involved with PAI, including Jorge de León, Regina José Galindo, Aníbal López, José Osorio, and María Adela Díaz; Santiago Sierra and Teresa Margolles each had a solo exhibition at Espacio Contexto in 2000.

- 7“Artist Video: Regina José Galindo: La víctima y el victimario,” March 26, 2015, Guggenheim website, https://www.guggenheim.org/video/regina-jose-galindo-la-victima-y-el-victimario-english-captioned.

- 8Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2015), 11.

- 9Rodolfo Arévalo S., “La huella del otro, su sombra: Contribución a un encuentro con E. Lévinas desde el arte de acción,” in Los Desaparecidos/Horror Vacui, 44. “La justicia, pese a su enorme enorme edificio y la inversión de los distintos gobiernos y la ayuda extranjera, no opera como se espera.” Translation by author.

- 10Alejandro Paz Navas, interview with the author, April 28, 2020. “La guerra en Guatemala se vivió en una manera muy opaca. Vivíamos en una ciudad, pero era muy difícil conocer que era lo que estaba sucediendo más allá de los límites de la ciudad, los métodos de información y comunicación estaban totalmente captados por una agenda del gobierno—del ejército—y no se entendía que era lo que estaba sucediendo.” Translation by author.

- 11Rodrigo J. Véliz and Kevin O’Neill, “Privatization of Public Space: The Displacement of Street Vendors in Guatemala City,” in Securing the City, 85.

- 12Alejandro Paz Navas, interview with the author, April 28, 2020. See also “Alejandro Paz Navas Talks About His Work,” February 9, 2019, Colección Cisneros website, https://coleccioncisneros.org/content/alejandro-paz-navas-talks-about-his-work.