Mail art, we know, is an excuse, we are interested in more important things that have to do with ourselves, our families, our people. If we accept this, differences are dissolved; after so much drama and so much blood we must discern who our true enemies are. —Clemente Padín, letter to Mauricio Guerrero, January 8, 1985

ARTIST ARM YOURSELF! Vlado Martek (Yugoslavia), in Poema Colectivo Revolución, 1981

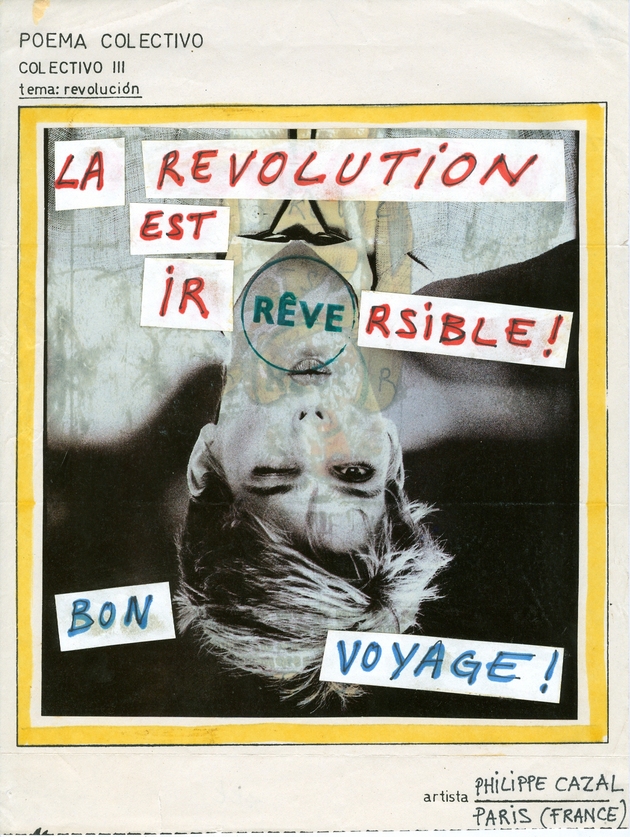

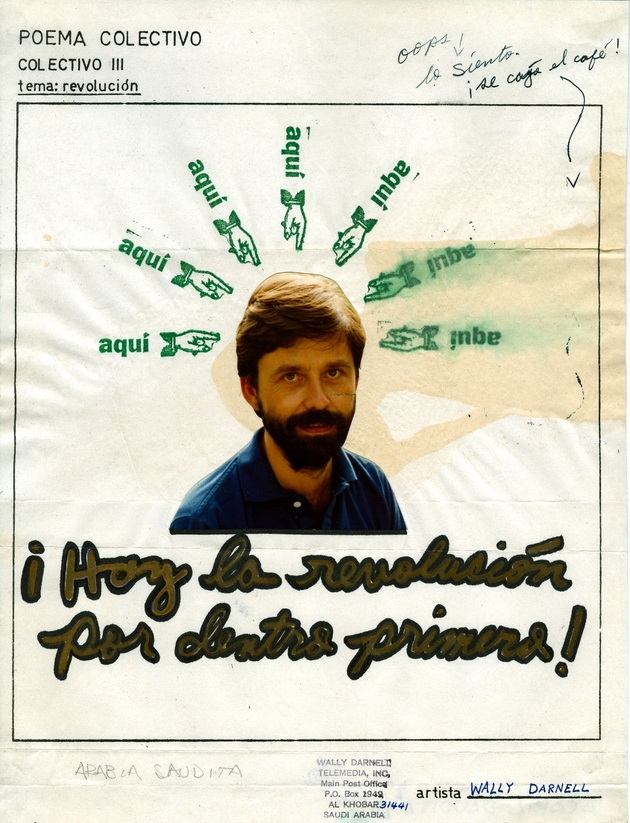

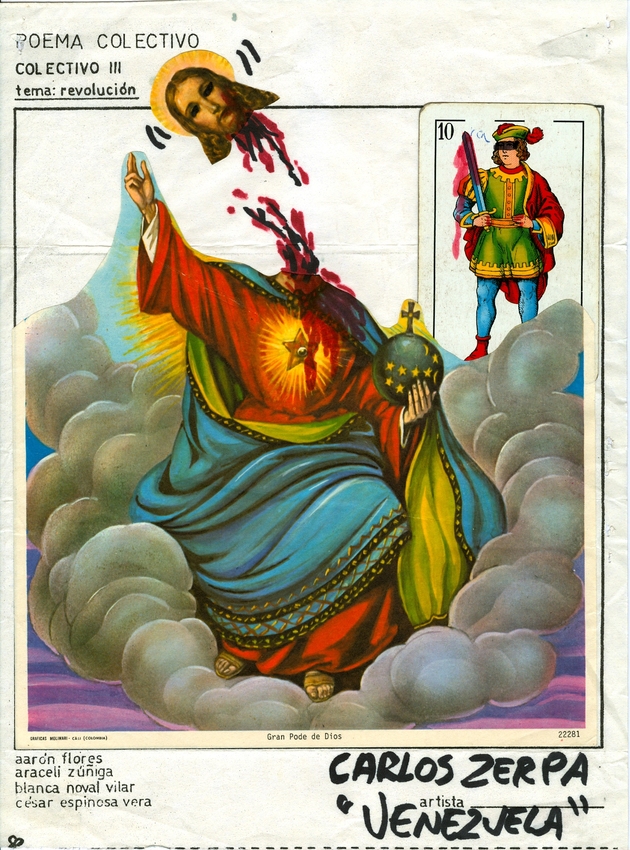

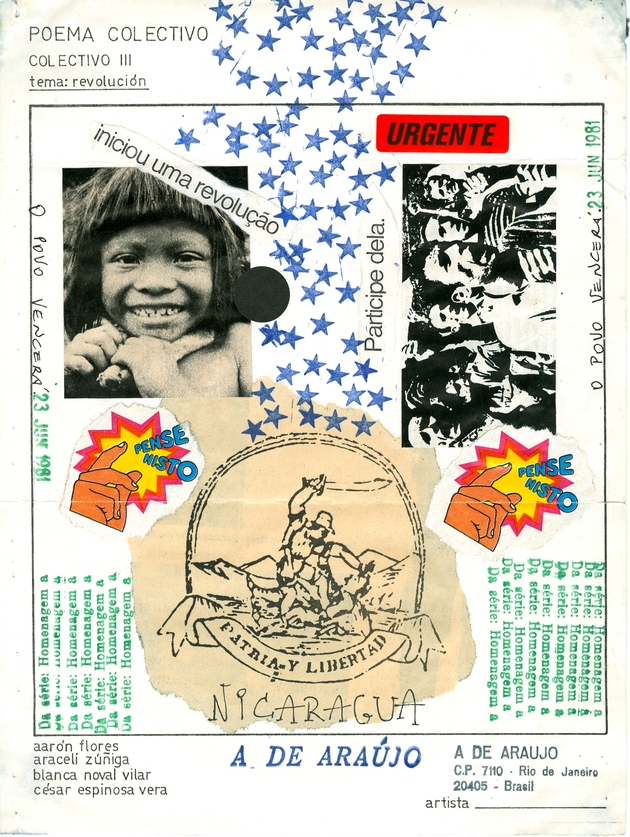

In 1981, Colectivo-3 disseminated its first project, Poema Colectivo Revolución (Collective Poem Revolution), from Mexico City to an international network of mail artists. The format was simple: an invitation in the form of a letter-size sheet with a wide border framing a blank rectangular space that served as an invitation to intervention. Printed at the top were the words “COLLECTIVE POEM / COLLECTIVE III / theme: revolution.” At the bottom was a space designated for the name of the artist/inventor/intervener.

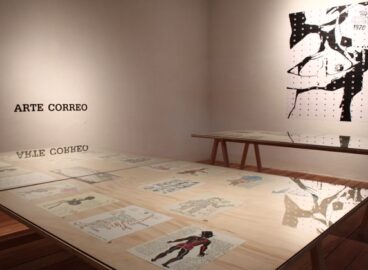

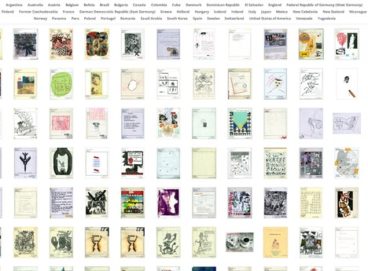

What a simple provocation, or rather, how complex! Today, in light of the demonstrations that have been happening around the world and the hopes for strongly desired transformations, initiatives for the formation of new communities and transnational urban resistance groups have sparked the urge to reactivate this (time) “bomb”1The word “bomb” appears frequently as a metaphor for mail art. See the Chilean-Venezuelan artist Dámaso Ogaz’s “Mail Art: a homemade bomb” and the epigraph to Paulo Bruscky’s 1976 “Arte Correio e a grande rede: hoje a arte é este comunicado” (Mail art and the wide network; today, art is this communiqué) (republished in 1981 by Alexis Bracho, Ediciones-Producciones HAMBRE-DADA, Venezuela, s/f. Clemente Padín Archive, Montevideo, Uruguay). In 1973 the Argentinian artist Carlos Ginzburg circulated in the mail art network a series of envelopes bearing on the outside the words “ENVELOPE-BOMB” and on the inside “LATINAMERICAN ART.” that, after more than three decades, continues to provoke, giving rise to new questions and new tools for artistic and activist practice. What would the collective poem of the revolution we want today be like? Would it correspond on any level to the diverse ensemble of the more than three hundred interventions2The 360 interventions were exhibited for the first time soon after the proposal was initiated in the 1980s, and more recently in the exhibition Arte Correo (Mail Art), curated by Mauricio Marcín, in the Museum of the City of Mexico from October 2009 to February 2010 and in the Philatelic Museum of Oaxaca from February to June 2011. Forty-nine works are reproduced in the show’s catalogue: Mauricio Marcín, ed., Arte Correo (Mail Art) (Barcelona: RM Verlag; D. R. Museo de la Ciudad de México, 2011). from forty-five countries that, in the early 1980s, were sent to Mexico to compose the Poema Colectivo Revolución?

If we imagine that the answer is “yes,” it is because we still have pending issues to resolve with the vital energy that mobilizes today’s generation. Again, if “yes,” it is because there is an ineluctable relationship between these two distinct moments and because mail art, the alternative artistic network that once connected people trans-geographically, now connects our demands on a transtemporal plane. If “no,” it’s because we believe that these artistic, creative, marginal, and collective strategies were effective in their time and that we should learn and appropriate from them, but definitively translate them into the present—or, in Haroldo de Campos’s term, to transluciferar them.3Brazilian poet and theoretician Haroldo de Campos defines the verb transluciferar as follows: to “travel a path configured by poetic function, apprehending it at the start and reinscribing it . . . in the language of the translator, to arrive at the transcreated poem as an isomorphic re-projection of the original poem.” Haroldo de Campos, “Transluciferação mefistofáustica,” trans. Fernanda Nogueira, in Deus e o Diablo no Fausto de Goethe (São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981), pp. 179–209.

The originators of Poema Colectivo Revolución were the Mexican artists Aarón Flores, Araceli Zúñiga, Blanca Noval, and César Espinosa, who in 1981 decided to form Colectivo-3. At that time, the group tried to reestablish the work begun by their former group, El Colectivo, whose demands were closely connected to those of other Mexican collectives that emerged in the 1970s, among them, Grupo Suma, Taller de Arte Independiente (TAI, Independent Art Workshop), and the Grupo Proceso Pentágono.4El Colectivo (1977–79) becomes Colectivo-3 (1981–85). El Colectivo was an association of socio-urban artists founded by Araceli Zúñiga, Aarón Flores, César Espinosa, Francisco Marmata, Blanca Noval, Pablo Espinosa “Gargaleón,” and Antonio Álvarez Portugal. In 1982, a year after the dissemination of the Poema Colectivo Revolución, Colectivo-3 was constituted by César Espinosa, Araceli Zúñiga, and Humberto Miguel Jiménez. That same year, Aarón Flores and Blanca Noval would join Mauricio Guerrero, Jesús Romeo Galdámez, and Carmen Medina in founding the collective Solidaridad Internacional por Arte Correo, which initially would include the intermittent participation of César Espinosa. The collective would be transformed into Solidarte/Mexico when nuclei began to emerge in other countries—Solidarte/France, Solidarte/Brasil, Solidarte/Australia, Solidarte/Italy, Solidarte/England—and would continue until 1986. Further information on the collectives is given in César Espinosa and Araceli Zúñiga, La Perra Brava: Arte, crisis y politicas culturales (The angry bitch: art, crisis, and cultural politics) (Mexico, City: STUNAM, UNAM, 2002). See especially the chapters “In the Eighties, Mail Art and Visual Poetry” and “Mail Art,” pp. 124–31. See also Mauricio B. Guerrero Alarcón, “El Arte Correo en México: origen y problemática en el periodo 1970–1984” (Mail art in Mexico: origins and problematic in the period 1970–1984) (bachelor’s degree thesis, UNAM-ENAP, 1986), p. 143. Together, these associations constituted the Frente Mexicano de Grupos Trabajadores de la Cultura (Mexican Front of Cultural Workers Groups).5The Mexican Front of Cultural Workers Groups formed in 1978 to solidify the link with popular mass movements, especially the struggle of the Nicaraguan populace. The Front included the artists’ groups Proceso Pentágono, Taller de Arte e Ideología—TAI, Suma, Mira, El Colectivo, Tetraedro, Grupo de cine Octubre, Germinal, Caligrama, Si usted sabe ler [sic], La Perra Brava (associated with the university union), the Federación Latinoamericana de Periodistas, Libro Acción Libre (an editorial cooperative directed by Felipe Ehrenberg and associated with Beau Geste Press), etc. The invitation to the group’s mail art exhibition, America en la Mira, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Morelia (Michoacán, Mexico) in 1978, elicited memorable responses denouncing violations of the right to freedom of speech on the continent and demanding the release from prison of Uruguayan mail artists Clemente Padín and Jorge Caraballo. By the early 1980s cultural workers’ collective discussions focusing on individual projects or on individual positions opposing institutional and state policies and dictates had given way to the challenge of generating demands that would connect critical issues worldwide, taking advantage of the platform that the mail art network had developed in the 1970s.

The Poema Colectivo Revolución elicited one of the largest responses of any invitation generated by these mail art collectives. Included in the program of the Jornada de Solidaridad con la Revolución Sandinista (Solidarity Conference for the Sandinista Revolution) promoted by the Mexican Front of Cultural Workers Groups in May 1981, the Sandinista Revolution was presented by members of Colectivo-3 as a “didactic element.” They had conceived the entire project as a collective poem dedicated to the triumph of the revolution then taking place in Nicaragua.

Nicaragua: Point of Departure and Translation

The revolution in Nicaragua placed that country under the constant surveillance of the United States, which, in its engagement with the Cold War, was determined to stop the revolutionary movement. If the new Nicaragua’s political, social, and cultural agendas were not aligned with those of the former Soviet Union, they were even less so with those of the United States. The Popular Sandinista Revolution mixed economics with a pluralist politics and managed to initiate democracy in Nicaragua: the Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) established an important democratic precedent in the nation’s history when it peacefully ceded power after losing the elections in 1990.

The revolution signaled the cultural encounter of Nicaragua with Nicaragua itself, with its deep roots, its strong traditions, and its own forms of expression. Nicaraguans committed to social struggles and justice—above all, Augusto César Sandino and Carlos Fonseca, formerly stigmatized as outlaws and terrorists—became celebrated, subverting the symbol of the “national hero.” The campesinos (peasants), urban workers, and the middle class were no longer merely subjects of Nicaraguan history; instead they had transformed themselves into its driving force. The country began to see itself as multilingual, multiracial, and multicultural. Through this rebirth, everything Nicaraguan was held in the highest regard. Nicaraguan dance, theater, literature, painting, and music were a large part of the new political agenda; popular art forms, previously seen as humble crafts, were now recognized for their value and relevance for local modernity. The small nation, immersed in the task of freeing itself and reclaiming its own identity and sovereignty, transformed itself into a paradigm as much within its own territory as internationally.

To preserve the dynamism of the changes that were taking place, calls for reclaiming Nicaragua’s status as a self-governing nation grew domestically as well as abroad. As a result of this international reach, the memory of the country’s political experiment belongs to us all. And despite the efforts to destroy its traces,6The publication, The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979–1992, conveys that the United States government, for example, strongly influenced the massive destruction of murals produced at that time in support of the Sandinista revolution, and did the same in three Latin-American countries (Chile, Panama, and Nicaragua), and more indirectly in a fourth: Colombia. The author David Kunzle argues that publication was an effort “to change a political system that abuses both people and art around the world.” David Kunzle, The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979–1992 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), p. ix. its memory has been disseminated and registered in the collective imaginary and in the works of artists around the world who were affected by this experience.7Many exhibitions related to Latin America traveled to the Museo de la Solidaridad de Managua, among them, Mailart aus Lateinamerika, organized by Clemente Padín in 1984 at the DAAD Galerie in Berlin, and Desaparecidos Políticos de Nuestra América, inspired by the Solidarte/Mexico group, which received an honorable mention at the 1984 Havana Biennial.

Even though the Poema Colectivo Revolución took the Nicaragua Revolution as a topic for aesthetic intervention, it was clear that revolutionary experience around the world went beyond this reality. Actually, every element of the project (meta)signified and incorporated this wider view. To begin with, the very fact of the poem’s collective creation constituted a revolution, as it blatantly broke with the principles of authority and the attendant paradigm of individualism. The feeling of community; the precept of solidarity; the use of time to non-utilitarian ends; the demonstration of a possible union beyond geographic, national, class, and racial boundaries, were thought to be realized within the logistics of the mail art network—from the contribution of many, through the multiplicity of voices. There was, from each place, a disclosure, a unifying multitude of singularities.

This collective “way of doing” occurred frequently in mail art, especially in the 1980s. An individual or a group would invite members of the network to participate in a project with a specific theme; in this way, dialogues were established directly and without intermediaries. The invitations defended a democratic principle: as a matter of course, all works received were included in the final collective piece without concern for aesthetic quality. In turn, the multiplicity of dialogues made up what could be considered a “work” of mail art. With this type of open call, anyone who received an invitation from the mail art network or simply desired to interchange their artistic/political productions could immediately become part of its constitutive framework.

This, as well as innumerable other experiences of artistic networks of marginal communication in 1970s Latin America, would become part of another strategy of mobilization: the formation of collectives. The Poema Colectivo Revolución coincided with many others that emerged in the mail art network in Latin America. Many of the artists’ collectives that had formed in the 1980s as a strategy of mobilization initiated poetic-political projects with popular resistance movements and denounced the tension and harassment experienced in countries such as Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, as well as in countries with dictatorial governments in the Southern Cone.

Even artists and activists from countries not officially under dictatorships felt themselves questioned, held in contempt, or affected not just by the situation of others but also by situations that affected everyone and were the cause of the dissatisfaction, unrest, and critique of the economic, social, and artistic systems. From its origins in poetic and activist practices, the Poema Colectivo’s collective pronouncement called for the broadening of public manifestations and actions in various contexts. In this way, by becoming manifest in a foreign territory, the project came to constitute a common place that more or less directly connected these different historical and political circumstances.

It was, then, necessary to demonstrate a collectivity, one seemingly so dispersed and only connected by the same long-distance channel of communication. The desire for international and, at the same time, local change, is interwoven in the Poema’s proposal to link contexts and histories and share modi operandi through fundamental and interdependent political concepts of revolution on macro- and micro-political levels. For César Espinosa and Araceli Zúñiga, the Poema Colectivo Revolución incorporated the following powerful messages:

“We believe that the Poema Colectivo Revolución, as a semiotic entity, brings together an international ideological mosaic, whose variants could be used to map criteria and strategies for artistic and cultural internationalism. Today in Mexico, we maintain that visual poetry can signify a revolutionary act, as much in aesthetic terms as to empower the signifying capacities of the worker majority, in its graphics, its press, and in popular communication.”8Araceli Zúñiga and César Espinosa, “Poema Colectivo Revolución,” in Arte Correo [Mail Art], ed. Mauricio Marcín (Barcelona: RM Verlag; D. R. Museo de la Ciudad de México, 2011), p. 190. Originally published in the catalogue to the exhibition Poema Colectivo Revolución, at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM), Xochimilco, in 1983.

The artists’ declaration takes note of a critical assumption that remains valid: the control of the circulation and distribution of images that run counter to the imposed social order and established modes of thought and ways of life. The power of visual poetry is rooted precisely in the possibility for the exhaustive production of counter-images, that is, visual images capable of rupturing the order of thought—the established epistemological structures—in the politics of permissible circulation and in docile subjectivities.

Poetry: A Form of Marginal, Utopian Resistance

The Poema Colectivo Revolución proposal was dispersed to seven hundred contacts in the mail art network. Responses were received from the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, and the islands of the Pacific. The project demonstrates that the importance of this artistic intervention lies more in the act of communication than in the creation of an art object. This is why Blanca Noval and Aarón Flores highlight that what was revolutionary—(meta)critically, in broad terms—was the mail art network itself. In its transformation, production, and wide circulation of the artwork at the margin of the canons of the unique, unrepeatable work of genius, the market, the galleries, the juries, and others, the network demonstrates a fundamental demand for dialogue and participation.9Unpublished interview with the author, May 31, 2012.

Among the responses to the Poema Colectivo Revolución’s invitation were some strikingly trenchant messages, such as that from the Argentinian artist Graciela Gutiérrez Marx. On June 21, 1981, she wrote, “Poetry is our utopian marginal resistance,” her handwriting spilling into the margin. Her words signal the crucial importance of resisting the pressure to devote one’s life to a capitalist system that functionalizes, homogenizes, and normalizes singularities in order to feed its implacable cycle of production and consumption. They also recall colonial conditions not only in Latin America but also in all places construed as global “margins.” One who resists and insists on living “with poetry,” producing a poetic discourse of f(r)ictions within these contexts, performs a heroic task.

Other contributions to the Poema Colectivo Revolución include César Espinosa’s ironically titled “How to make a revolution,” which depicts small silhouettes of generic bodies and flags; the slogans of the Chilean mail artist Guillermo Deisler, who was at that time exiled in Bulgaria: “Revolution is a perspective of history, Revolution is a measure of social hygiene, Revolution is an illogical ingenuity, Revolution is many evolutions, Revolution is the ‘Fly-Tox’ of society, Revolution is a page-turner of history, Revolution is you and I, endlessly”; Brazilian artist Paulo Bruscky’s signaling of disputed territory in his bipolar diagram of the world, which has Latin America as its focal point, spread across various situations and temporalities; symbols of Trotskyism and the Fourth International; and hundreds more supporting the supposition that questions are always posed by collectives even when they are articulated by a single person.

The countries mentioned in the works did not fit the description of nation states; rather, their names evoked conditions of internal struggle and elicited international solidarity with the people of those regions. An example of this is Jesús Romeo Galdámez’s piece referencing the armed FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front) in El Salvador. The artist’s text gives an indispensable explanation: “The people opt for the only alternative that is left to vindicate the most just aspiration: liberty, the voice, the armed struggle. El Salvador will triumph!”

The revolutionary imaginary is a collective of diverse voices that shoot out in different directions. Revolution in one voice, under one flag is, in this case, a truly impossible, utopian undertaking. Revolution depends on the multiple voices that set it in motion and sustain it. There is a common project, a common desire, a dialogue, and a common space for intervention, multiple articulations, varied materials, singular ways of speaking, and diverse ways of doing. By inviting people to contribute to the Poema Colectivo Revolución, Colectivo-3 did not intend to heighten the consciousness of those receiving these materials. Its purpose was not to represent what was happening in local or world events, but rather to generate conflictive images, to bring interference, intervention, and noise—life drives—into official mass circulation. The end result embodies the many stages in the realization of the piece, from its initial mailing to hundreds of individuals to the reception of their responses communicating positions, concepts, and ways of life. Given this complex process, it’s undeniable that the works’ formal aesthetics are less important than the call to action that the proposal represents, a call that succeeds in democratizing the production and circulation of poetic works, eliciting graphics that break with traditional aesthetics, received ideologies, and traditional ways of conducting politics.

In a world of images and imaginaries that are controlled so as not to generate affect, it is necessary to create channels for the circulation of alternative information intended to counter that distributed by the mass media. The mail art network thus managed to evade the control and censorship of information and to deregulate the production of images and their designated space of circulation, thus interfering with the dictates of that which could be seen and known. By its very presence, mail art argued for a form of collective visibility that takes on the risks of generating an arena for debate and of taking to their limit normative, instituted, perceptual constructs and the circulation of “permitted” knowledge and information.

The Poema Colectivo Revolución graphically presents the unforeseen and unexpected. Its medium will never be outmoded—one need only reflect on how long it has been since paper was first used to carry information from one person to another. The means of communication and tools tend only to complement one another. And it is obvious that it is not only a question of medium, but rather, primordially, of will. Thus, formal improvement is less important on a temporal diagram of the network.

The “way of doing” that is manifest in this project was later replicated by the collectives that were transformed by it. Solidarte (Solidaridad Internacional por Arte Correo [International Solidarity by Mail Art]),10For information on Solidarte, see Sol Henaro et al., “Internacionalismos” [Internationalisms], in Perder la Forma Humana: Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (Losing the human form. A seismic image of the 1980s in Latin America), ed. Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Madrid: MNCARS, 2013), pp. 154–164. The publication was issued on the occasion of the exhibition of the same title held at the Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid, October 2012 to March 2013. for example, based in Mexico City, served as the model for branches in other countries. A few years later, Colectivo-3 conceived the memorable international proposal Maratón de Arte Correo 1984 en 1984: ¿qué futuro buscamos? (Mail art marathon 1984 in 1984: what future are we looking for?), which was shown in various Mexican venues, including the Sociedad Mexicana de Artistas Plásticos (Mexican Society of Plastic Artists) and Casa del Lago of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Colectivo-3’s final activities as a collective took place in 1985 at the Salón de Espacios Alternativos del Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (Salon of Alternative Spaces of the National Institute of Fine Arts).

The Poema Colectivo Revolución was first exhibited at the Pinacoteca de la Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (Art Gallery of the Autonomous University of Puebla) in 1982. In 1983 it was shown in the Xochimilco center at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana en la Ciudad de México (Autonomous Metropolitan University of the City of Mexico), and from 2009 to 2010 it was displayed in the exhibition Arte Correo (Mail Art), organized by Mauricio Marcín in the Museum of the City of Mexico. Today the work is archived under the supervision of Araceli Zúñiga and César Espinosa, former members of Colectivo-3.

To conclude, the main lesson of this artistic experience is that it doesn’t matter which tactic or tools one employs. What is really important is what the impulse is based on, which necessities it responds to, through which urgencies it implements aesthetic practice, and finally, which battle grounds it establishes.

*This is the third in a series of texts written by the author about mail art. The first two are as follows:

Nogueira, Fernanda and Fernando Davis. “Gestionar la precariedad. Potencias poético políticas de la red de arte correo” [Managing Precariousness. The Poetic-Political Power of Mail Art Network]. Madrid: Artecontexto 24 (2009): 34–41. Available online, https://artecontexto.com/hemeroteca/revista-24/

Nogueira, Fernanda. “El cuerpo político más allá de sus límites. Clemente Padín y el flujo postal” [The political body beyond its boundaries. Clemente Padín and the postal flows] in Arte Correo [Mail Art], edited by Mauricio Marcín, 77–92. Barcelona: RM Verlag; D. R. Museo de la Ciudad de México, 2011.

Lea el texto en español aquí.

- 1The word “bomb” appears frequently as a metaphor for mail art. See the Chilean-Venezuelan artist Dámaso Ogaz’s “Mail Art: a homemade bomb” and the epigraph to Paulo Bruscky’s 1976 “Arte Correio e a grande rede: hoje a arte é este comunicado” (Mail art and the wide network; today, art is this communiqué) (republished in 1981 by Alexis Bracho, Ediciones-Producciones HAMBRE-DADA, Venezuela, s/f. Clemente Padín Archive, Montevideo, Uruguay). In 1973 the Argentinian artist Carlos Ginzburg circulated in the mail art network a series of envelopes bearing on the outside the words “ENVELOPE-BOMB” and on the inside “LATINAMERICAN ART.”

- 2The 360 interventions were exhibited for the first time soon after the proposal was initiated in the 1980s, and more recently in the exhibition Arte Correo (Mail Art), curated by Mauricio Marcín, in the Museum of the City of Mexico from October 2009 to February 2010 and in the Philatelic Museum of Oaxaca from February to June 2011. Forty-nine works are reproduced in the show’s catalogue: Mauricio Marcín, ed., Arte Correo (Mail Art) (Barcelona: RM Verlag; D. R. Museo de la Ciudad de México, 2011).

- 3Brazilian poet and theoretician Haroldo de Campos defines the verb transluciferar as follows: to “travel a path configured by poetic function, apprehending it at the start and reinscribing it . . . in the language of the translator, to arrive at the transcreated poem as an isomorphic re-projection of the original poem.” Haroldo de Campos, “Transluciferação mefistofáustica,” trans. Fernanda Nogueira, in Deus e o Diablo no Fausto de Goethe (São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1981), pp. 179–209.

- 4El Colectivo (1977–79) becomes Colectivo-3 (1981–85). El Colectivo was an association of socio-urban artists founded by Araceli Zúñiga, Aarón Flores, César Espinosa, Francisco Marmata, Blanca Noval, Pablo Espinosa “Gargaleón,” and Antonio Álvarez Portugal. In 1982, a year after the dissemination of the Poema Colectivo Revolución, Colectivo-3 was constituted by César Espinosa, Araceli Zúñiga, and Humberto Miguel Jiménez. That same year, Aarón Flores and Blanca Noval would join Mauricio Guerrero, Jesús Romeo Galdámez, and Carmen Medina in founding the collective Solidaridad Internacional por Arte Correo, which initially would include the intermittent participation of César Espinosa. The collective would be transformed into Solidarte/Mexico when nuclei began to emerge in other countries—Solidarte/France, Solidarte/Brasil, Solidarte/Australia, Solidarte/Italy, Solidarte/England—and would continue until 1986. Further information on the collectives is given in César Espinosa and Araceli Zúñiga, La Perra Brava: Arte, crisis y politicas culturales (The angry bitch: art, crisis, and cultural politics) (Mexico, City: STUNAM, UNAM, 2002). See especially the chapters “In the Eighties, Mail Art and Visual Poetry” and “Mail Art,” pp. 124–31. See also Mauricio B. Guerrero Alarcón, “El Arte Correo en México: origen y problemática en el periodo 1970–1984” (Mail art in Mexico: origins and problematic in the period 1970–1984) (bachelor’s degree thesis, UNAM-ENAP, 1986), p. 143.

- 5The Mexican Front of Cultural Workers Groups formed in 1978 to solidify the link with popular mass movements, especially the struggle of the Nicaraguan populace. The Front included the artists’ groups Proceso Pentágono, Taller de Arte e Ideología—TAI, Suma, Mira, El Colectivo, Tetraedro, Grupo de cine Octubre, Germinal, Caligrama, Si usted sabe ler [sic], La Perra Brava (associated with the university union), the Federación Latinoamericana de Periodistas, Libro Acción Libre (an editorial cooperative directed by Felipe Ehrenberg and associated with Beau Geste Press), etc. The invitation to the group’s mail art exhibition, America en la Mira, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Morelia (Michoacán, Mexico) in 1978, elicited memorable responses denouncing violations of the right to freedom of speech on the continent and demanding the release from prison of Uruguayan mail artists Clemente Padín and Jorge Caraballo.

- 6The publication, The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979–1992, conveys that the United States government, for example, strongly influenced the massive destruction of murals produced at that time in support of the Sandinista revolution, and did the same in three Latin-American countries (Chile, Panama, and Nicaragua), and more indirectly in a fourth: Colombia. The author David Kunzle argues that publication was an effort “to change a political system that abuses both people and art around the world.” David Kunzle, The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979–1992 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), p. ix.

- 7Many exhibitions related to Latin America traveled to the Museo de la Solidaridad de Managua, among them, Mailart aus Lateinamerika, organized by Clemente Padín in 1984 at the DAAD Galerie in Berlin, and Desaparecidos Políticos de Nuestra América, inspired by the Solidarte/Mexico group, which received an honorable mention at the 1984 Havana Biennial.

- 8Araceli Zúñiga and César Espinosa, “Poema Colectivo Revolución,” in Arte Correo [Mail Art], ed. Mauricio Marcín (Barcelona: RM Verlag; D. R. Museo de la Ciudad de México, 2011), p. 190. Originally published in the catalogue to the exhibition Poema Colectivo Revolución, at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM), Xochimilco, in 1983.

- 9Unpublished interview with the author, May 31, 2012.

- 10For information on Solidarte, see Sol Henaro et al., “Internacionalismos” [Internationalisms], in Perder la Forma Humana: Una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina (Losing the human form. A seismic image of the 1980s in Latin America), ed. Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Madrid: MNCARS, 2013), pp. 154–164. The publication was issued on the occasion of the exhibition of the same title held at the Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid, October 2012 to March 2013.