Did 1993 mark a watershed for “contemporary Chinese art” in the then increasingly globalized art world? In this essay Peggy Wang discusses exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art held overseas in the year 1993, notably China Avant-Garde in Berlin, China’s New Art, Post-1989 in Hong Kong, and the Venice Biennale. Analyzing various readings of works by artists such as Wang Guangyi, Yu Youhan, Fang Lijun, and Zhang Peili, the author traces how 1993 served as a starting point for the problematic reception of contemporary Chinese art. She also argues for previously neglected interpretations of these exhibitions, and shows how they can be further studied to reread the state of contemporary Chinese art in the early 1990s.

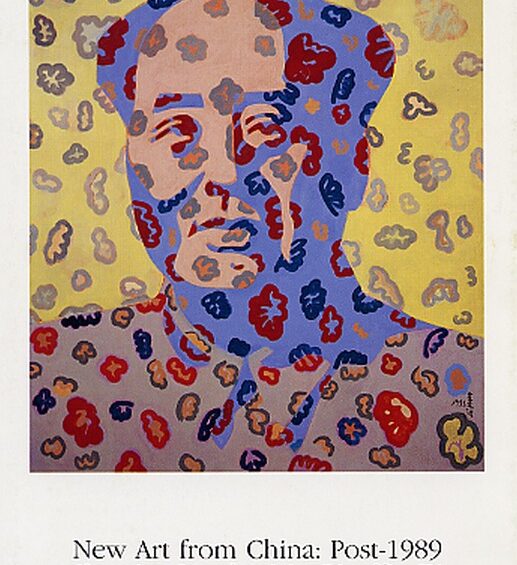

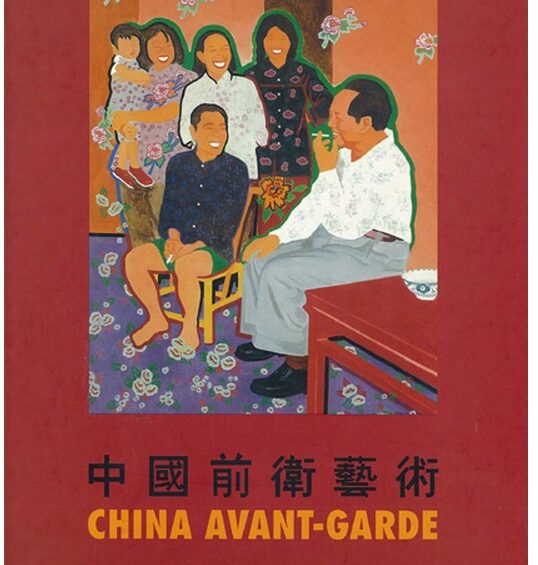

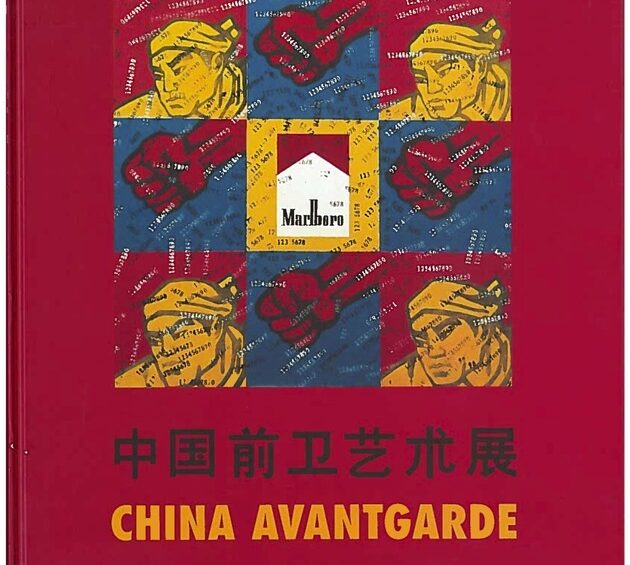

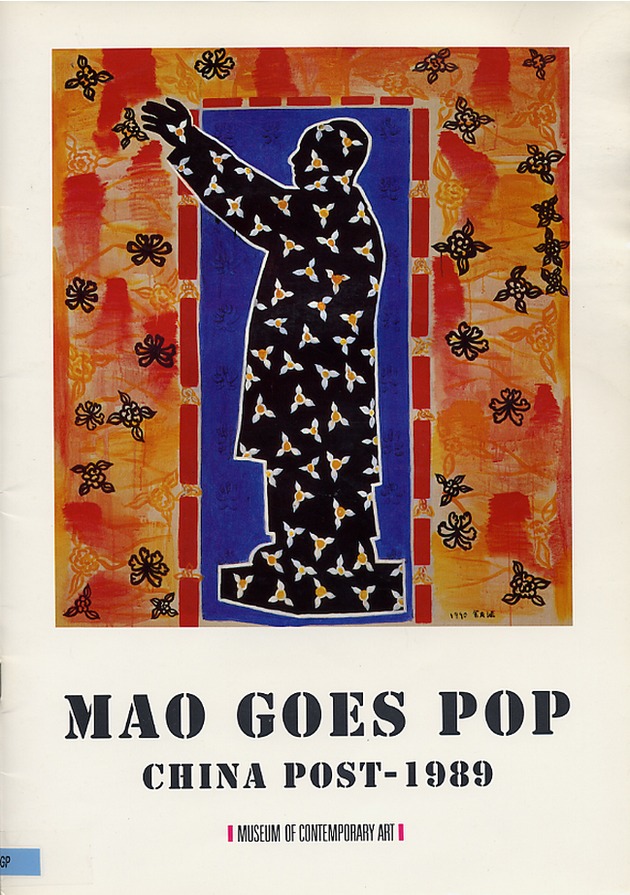

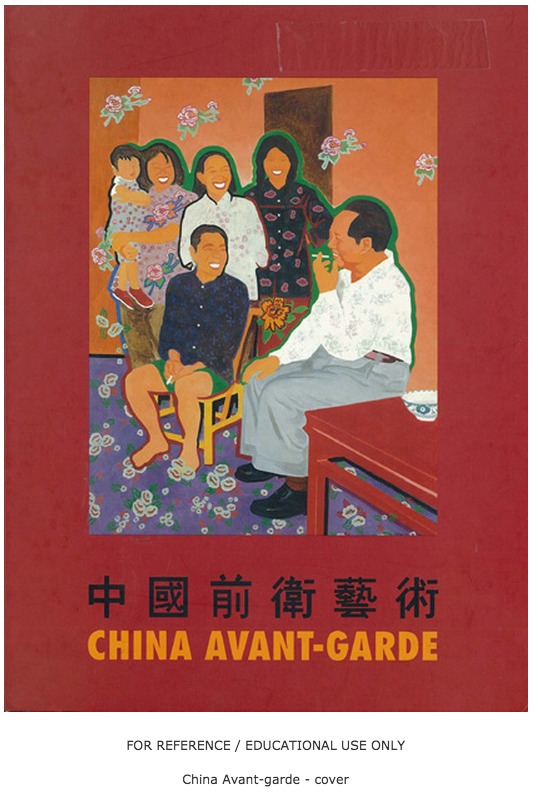

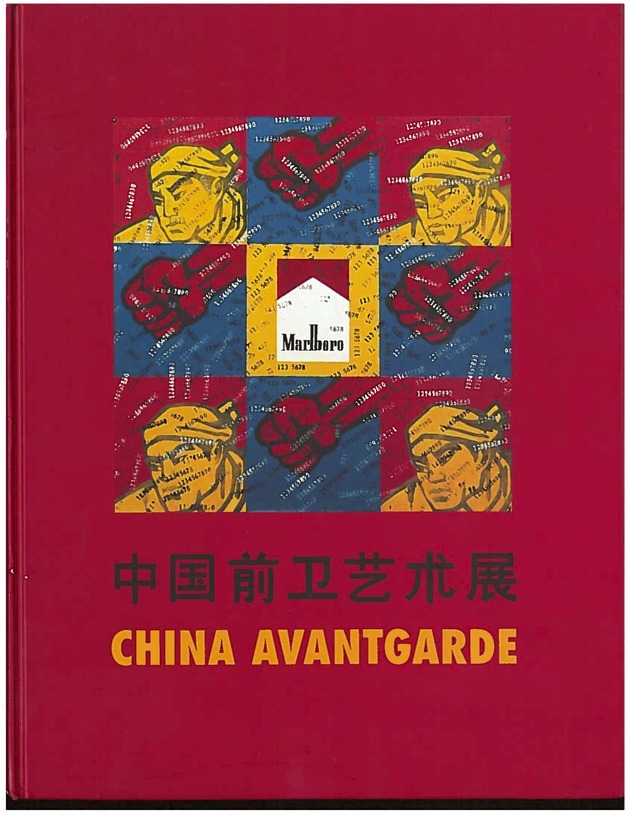

In 1993 exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art were rolled out in rapid succession from Hong Kong to Australia, across Europe, and in the United States.1In January, Johnson Chang and Li Xianting’s exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989 opened in Hong Kong (January 31–February 25, 1993). An abbreviated version of the exhibition traveled later that year to Australia under the title Mao Goes Pop: China Post-1989 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, June 2–August 15, 1993). Andreas Schmid, Hans van Dijk, and Jochen Noth’s exhibition China Avant-garde started at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (January 30–May 1993) and traveled to the Kunsthal Rotterdam (May 29–August 22, 1993), the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (September 4¬–October 24, 1993), and Kunshallen Brandst Klædefabrik, Odense, Denmark (November 12, 1993–February 6, 1994). Silent Energy, co-curated by David Elliot and Lydie Melpham, was shown at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (part 1: June 27–August 29, 1993; part 2: September 5–October 24, 1993). In June 1993, fourteen Chinese artists participated in a special exhibition titled_ Passage to the East_ at the Venice Biennale. Four Chinese artists were featured in the experimental Aperto section of the Biennale, and Chinese critic Kong Chang’an served as a member of the Aperto curatorial team. Two exhibitions were focused specifically on the diaspora: David Elliot and Lydie Mepham’s Silent Energy: New Art from China, held at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, and Gao Minglu and Julia F. Andrews’s Fragmented Memory: The Chinese Avant-Garde in Exile, at the Wexner Art Center in Columbus, Ohio. Although a handful of artworks had been shown in the United States and Europe before this, the sheer number of exhibitions and their occurrence in high-profile venues such as at the venerable Venice Biennale and the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin ensured that 1993 would be remembered as a milestone in the history of contemporary Chinese art.

This essay presents some of the ways in which these 1993 exhibitions have contributed—and continue to contribute—to understandings of contemporary Chinese art. In the first part of this essay, I investigate how the exhibitions’ naming and circulation of specific styles and artists disseminated enduring narratives about Chinese art and politics to an international public. Though the reception of contemporary Chinese art raised important questions about the mechanisms of canonization, the dominance of this discourse has also overshadowed alternative readings of the post-1989 contemporary Chinese art scene. The second part of the essay thus approaches the exhibitions before their controversial legacies took hold. When explored in this light, these exhibitions serve as testaments to an emerging and surprising energy in contemporary Chinese art during the early 1990s, a dynamism that is often overlooked within the prevailing narratives of tragedy and dissent.

Post-1989

In order to understand how these exhibitions were received, it is first necessary to examine the contexts and conflicts from which they emerged. In 1989 momentous shifts in art and politics deeply affected the way people perceived China and its position in the world, and in turn the assumptions with which they greeted these exhibitions four years later. On June 4, 1989, news media around the world captured the Chinese central government’s brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square. The fall of the Berlin Wall later that year, followed by the end of the Eastern Bloc and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1992, meant that by 1993 China was seen as occupying a strangely alienated position as the last major stalwart of Communism. In 1992 Deng Xiaoping—the de facto leader of China—embarked on his famed Southern Tour through the country’s coastal cities to call for renewed economic reform.2In 1978, Deng Xiaoping emerged as the paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China and the Communist Party of China. Although he stepped down as Chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1989, he maintained political influence among the political elite. On his 1992 Southern Tour, Deng—recognized as “the chief architect of China’s reform”—promoted the same reform policy that he had initiated in 1979. The reforms portended the rise of a new capitalist ethos in China and further contributed to the country’s ideologically conflicted image. Within this convergence of sociopolitical events and conditions—Chinese authoritarianism, the worldwide collapse of Communism, and a new domestic shift toward capitalist economic reform—contemporary Chinese art offered curious observers a window into a politically and culturally enigmatic place.

The year 1989 also witnessed historical changes in the art world. Coinciding with the events of June 4, the exhibition Magiciens de la terre opened at the Centre Georges Pompidou and the Grande Halle at the Parc de la Villette in Paris. Curated by Jean-Hubert Martin with the aim of bringing together the world’s centers and peripheries—including China—this landmark exhibition attempted to use a “universalist conception of the act of art creation” to provide an even playing field for the participating artists.3Pablo Lafuente, “Introduction: From the Outside In—‘Magiciens de la Terre’ and Two Histories of Exhibitions,” in Making Art Global (Part 2) (London: Afterall Books, 2013), p. 11. Art critics, particularly those from the “peripheries,” immediately panned Magiciens for ignoring the geopolitical and historical conditions that had led to the very center-periphery paradigm that the exhibition sought to redress. For example, artist-critic Rasheed Araeen charged: “The central concern remains the same old-fashioned debate about the relationship between modernism and the traditions of others. . . . The question is no longer only what the ‘other’ is but also how the ‘other’ has subverted the very assumptions on which ‘otherness’ is constructed by dominant culture.”4Rasheed Araeen, “Our Bauhaus others’ Mudhouse,” in Third Text 3, no. 6 (1989), p. 3. Just as Magiciens marked a commitment to expanding the reach of global contemporary art, it also generated great attention and momentum for commentary on how to fulfill that task responsibly. Artists and critics from the world’s peripheries called for subaltern voices to rise up and speak for themselves.5Throughout the 1990s, expatriate art critic and curator Hou Hanru was the most vocal participant in these discourses, particularly when speaking on behalf of diaspora artists. Efforts to expose and challenge the Western-centric global art world continue today. Most notably, the initiative to transform the global art world into multiple art worlds has been championed recently in Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg, and Peter Weibel’s exhibition The Global Contemporary. Art Worlds after 1989 (2011–2012). The accompanying publication, The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds (2013), significantly includes an entry on the 1993 exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989.

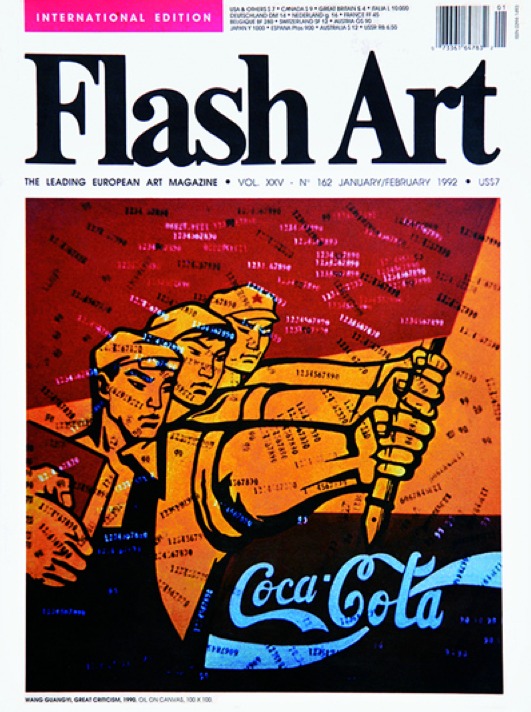

The 1993 exhibitions can thus best be situated against a background of ideological conflict, emerging critiques of global power dynamics, and cultural curiosity about China. With the expansion of the global art world after Magiciens de la terre, Western interest in the non-West was on the rise. Leading up to the 1993 Venice Biennale, the Milan-based international contemporary art magazine Flash Art ran a four-page spread on contemporary Chinese art by Kong Chang’an, a young art critic studying in Italy.6Chan Lauk’ung (pen name of Kong Chang’an), “Ten Years of the Chinese Avant-Garde: Waiting for the Curtain to Fall,” Flash Art 25, no. 162 (January/February 1992): pp. 110–114. Later tapped to be one of the curators of the Aperto section of the Venice Biennale, Kong was both well informed and eager to share his images and knowledge of the contemporary art scene in China. As Kong recalls, the editors of Flash Art seemed equally excited to receive these materials: “It was like they were waiting for this.”7Kong Chang’an, “Exhibition as Site—Extended case study (China 1993)” panel, Sites of Construction: Exhibitions and the making of recent art history in Asia symposium, Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, October 22, 2013. http://www.aaa.org.hk/Programme/Details/435. Kong went on to say that, from the time in 1991 when Achille Bonito Oliva and Helena Kontova were appointed co-directors of the Venice Biennale, every issue of Flash Art included an article about the upcoming iteration of this event. The editor of Flash Art, Giancarlo Politi, was Kontova’s husband. The magazine’s enthusiasm was confirmed by the appearance of Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism: Coca-Cola (1991) on the cover of the January/February 1992 issue.

Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism: Coca-Cola typifies the style known as Political Pop. Three men in the foreground—a worker, farmer, and soldier—stand unified in their postures and joined through a sense of fixed resolve. The figures’ exaggerated musculature, their depiction through black contour lines and flat colors, and the red flag behind their heads are all appropriated from early Cultural Revolution posters. Juxtaposed against these Socialist symbols is a swooping Coca-Cola logo at the bottom right of the picture, a sign of the proliferation of Western commodities in a new consumer culture. Characterized by bright colors, planar surfaces, and identifiable ideological symbols, Political Pop was quickly embraced by Western audiences for its graphic seductiveness and the legibility of its political references. Flash Art’s selection of this particular image presaged the 1993 exhibitions’ principal focus on Political Pop and Cynical Realism.

Art critic and curator Li Xianting coined the terms “Cynical Realism” and “Political Pop” in 1991. The label “Cynical Realism” first circulated in February 1992 in Li’s article for the Hong Kong publication Twenty-First Century. Though the article mentioned Pop, Li didn’t formally specify the term “Political Pop” until he began planning the 1993 exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989. He more fully theorized “Political Pop” in a 1992 article for the Taiwan-based magazine Art Trends, in which he wrote of the two styles: “They are both interested in the dissolution of certain systems of meaning and both attend to reality. Cynical Realism focuses on the senseless reality of the self, whereas Political Pop directly portrays the reality of dissolved meanings.”8Li Xianting, “Apathy and Deconstruction in Post-’89 Art: Analyzing the Trends of ‘Cynical Realism’ and ‘Political Pop’” Art Trends no. 1 (1992). Translation in Wu Hung, ed., with the assistance of Peggy Wang, Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, (New York: Museum of Modern Art), pp. 157–167. Li Xianting’s swift labeling and historicized interpretations helped to corral contemporary Chinese art into identifiable categories. Furthermore, his writings on these particular styles provided an early glimpse into post-1989 China for inquisitive audiences abroad. According to Li, these early articles attracted substantial critical attention and were subsequently excerpted in other overseas journals.9This is relayed in Li Xianting’s 2000 postscript to the 1992 Art Trends article cited in note 8. Postscript published in Li Xianting, Art is Not the Important Thing _(Jiangsu: Jiangsu Art Publishing, 2000), p. 306. Translation of original essay and postscript in Wu Hung, ed., _Contemporary Chinese Art, cited above in note 8. By 1993 the fact that works of Political Pop and Cynical Realism could be discussed as designated stylistic categories and accompanied by authoritative explanations made them all the more accessible and attractive for circulation.

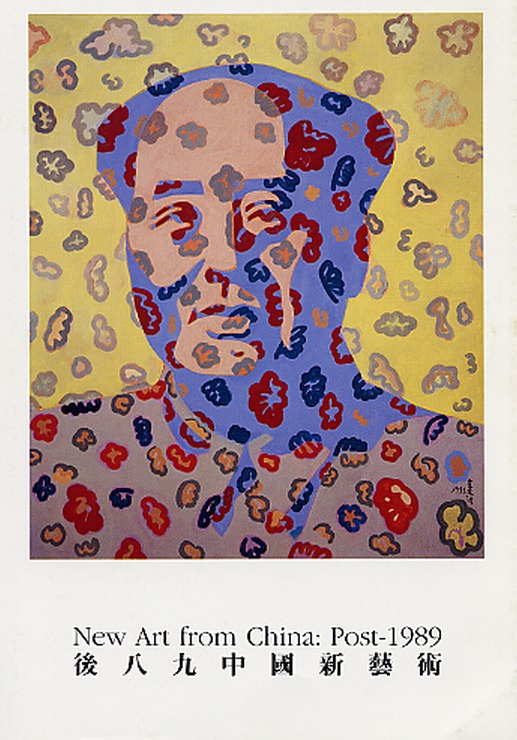

After making a splash on the cover of Flash Art, Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism series continued to receive widespread international exposure and media attention across multiple exhibitions in 1993. Wang Guangyi and Yu Youhan, the principal figures of Political Pop, were included in the three exhibitions in Hong Kong, Berlin, and Venice; moreover, their works received special attention in the promotional materials for these exhibitions. After the initial blockbuster showing of China’s New Art, Post-1989 in Hong Kong, the exhibition traveled in different iterations to Australia, Europe, and the United States. For London’s Marlborough Fine Art gallery, Yu’s Mao Decorated (1993) adorned invitation cards. In perhaps the most overt declaration of this trend, the condensed version of the exhibition in Sydney was titled Mao Goes Pop: Post-1989 and featured Yu’s The Waving Mao (1990) on its catalogue cover.10Later publicity materials followed suit: in 1997, the exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989 at the Salina Art Center, Salina, Kansas, featured The Waving Mao as well. Work by Liu Wei, a leading figure in Cynical Realism, was also widely publicized in ads for the exhibition in London. Similarly, Yu Youhan’s work Talking with Hunan Peasants (1991) graced the cover of the English and Chinese versions of the China Avant-Garde catalogue, while Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism—Marlboro (1990) was featured on the German version.

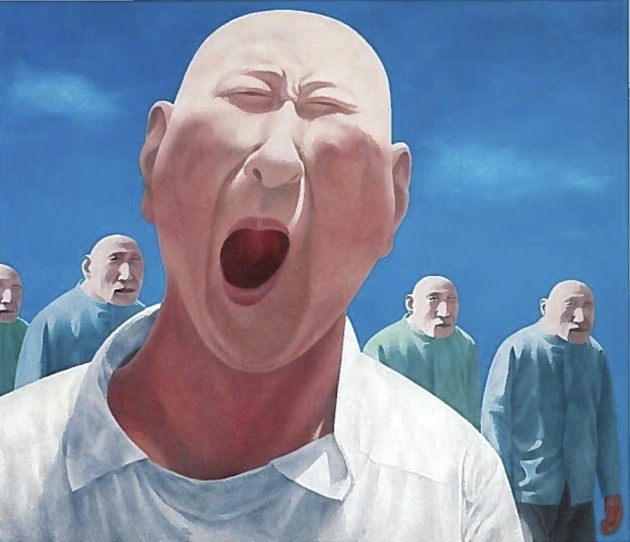

The 1993 exhibitions and the attention they received in the press made Political Pop and Cynical Realism tremendously popular among Western media and audiences. Featuring large faces and distorted perspectives, Cynical Realism shared with Political Pop a perceived streak of irreverence and satire. Fang Lijun, the leading figure of Cynical Realism, also exhibited at all three exhibitions. He, along with Wang Guangyi and Yu Youhan, enjoyed immediate success abroad. All three artists took part in China’s first-ever appearance at the São Paolo Biennial in 1994, and went on to have solo exhibitions and to participate in select group shows in Hong Kong and Europe throughout the decade.

In reviewing the catalogues and curatorial notes for these shows, it is perhaps surprising to see the vast array of writings and artists’ works. The catalogues for China Avant-Garde and China’s New Art, Post-1989 offer impressive frameworks that accommodate multiple perspectives. The essays in China Avant-Garde, in particular, expand well beyond art to include texts on experimental theater, music, and literature. Moreover, as the physical space at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt was limited, the curators included biographical details and images linked to forty-four artists beyond the sixteen who were shown. In Hong Kong, China’s New Art, Post-1989 similarly exhibited an enormous number of works, which were organized into six categories. Nevertheless, emphasis was on Political Pop and Cynical Realism: as Jane DeBevoise has calculated, about 45 percent of the images in the catalogue exemplified these two styles.11Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market: Chinese Contemporary Art in the Post-Mao Era (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishing, 2014), p. 268 n 13.

The ensuing media coverage further promoted this narrowed attention. Andreas Schmid, co-curator of the China Avant-Garde exhibition in Berlin, recalls: “The media echo was strong, but often shallow in nature. Too many newspaper articles favored the colorful, realistically painted, and figurative artworks on display because they were supposedly ‘easier’ to understand.”12Andreas Schmid, “The Dawn of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West” in Negotiating Difference: Contemporary Chinese Art in the Global Context, ed. Juliane Noth et al. (Weimar: VDG, 2012), p. 294. Franziska Koch studies this exhibition in depth in “‘China’ on Display for European Audiences? The Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art—China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993),” in Transcultural Studies no. 2 (2011): pp. 66–139. In particular, Schmid laments: “The media hardly noticed the more complex video works of Zhang Peili or the conceptual work of Geng Jianyi, or tried to understand them.”13Schmid, “The Dawn of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West,” p. 294. In contrast to the straightforward visual and political accessibility of Political Pop and Cynical Realism, Zhang Peili’s exhibited videos—30 x 30 (1988), Document on Hygiene, No. 3 (1991), Water: The Standard Version Read from the Cihai Dictionary (1992), and Homework No. 1 (1992)—lacked iconographic legibility for a foreign audience. Document on Hygiene, No. 3, for example, presents the artist washing a chicken over the course of twenty-four minutes and forty-five seconds. With no sound and little change in action, the video of this performance denies a comprehensive narrative reading. Though part of the meaning of the video is tied to the very absurdity of the depicted action and its non-narrative format, Zhang’s work was seen as overly opaque when compared to the visual allure and perceived political messages in Wang Guangyi’s and Fang Lijun’s canvases.

An unfortunate consequence of this limited focus on Political Pop and Cynical Realism was the misconception that these styles were representative of the entire contemporary Chinese art scene. Equally problematic were readings of the paintings as imitative of Western styles. One critic’s review of the Berlin exhibition reported: “There are signs, similar to those in recent Russian art, that younger painters have only just discovered Western Pop Art, so for Westerners there is a déjà vu quality about the work of such as [sic] Wang Guangyi or Yu Youhan.”14John Russell Taylor, “Trailblazing East and West,” The Times (UK), March 8, 1993. In this way, Political Pop confirmed international audiences’ existing views of China as culturally lagging and stylistically derivative of the West, where Pop had flourished decades earlier.

In December 1993 Andrew Solomon concluded the year with his seminal article “Their Irony, Humor (and Art) Can Save China” in the New York Times Magazine. The article, illustrated with works by Fang Lijun and Wang Guangyi, among others, included details of the effects that such exposure had had on cultural production inside China. Solomon described the scene at the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) in Beijing, where a community of painters resided, as “a mecca for Western tourists and journalists.” He wrote of the artists: “Many imitate each other, unimaginatively combining Cynical Realism and Political Pop. In fact, when you look closely at the paintings produced there, you feel that most of these artists are only a half step away from jade carvers or other practitioners of local handicraft for foreign consumption.”15Andrew Solomon, “Their Irony, Humor (and Art) Can Save China,” The New York Times Magazine, December 19, 1993, p. 66. Solomon’s observations speak to the swift material consequences of the 1993 exhibitions. The convergence of international ambition with foreign consumers led to styles becoming rote formulae and the assumption that sheer technical labor could be a fast track to success. Yet as Solomon directs critique at Chinese cultural producers’ reactions to Western tastes, he leaves out more critical commentary on how Western media and audiences can be complicit in perpetuating reductive understandings of contemporary Chinese art. This is especially important given the magazine’s own choice to feature Fang Lijun’s painting Series 2, No. 2 (1991–1992) on the cover. Though Solomon’s lengthy article incorporates discussions of conceptual artists and their works—including Zhang Peili’s Document on Hygiene, No. 3—Fang Lijun’s distorted bald man with wide-open mouth and closed eyes remains the powerful representative image of this 1993 written exposition. In later histories of contemporary Chinese art and Fang’s own work and life, the New York Times Magazine cover figures prominently as a seminal moment in assuring the popularity of Cynical Realism with a foreign readership.16Karen Smith, Nine Lives: The Birth of Avant-Garde Art in New China, updated ed. (China: Timezone 8, 2009), p. 161. All subsequent citations refer to this edition.

Solomon’s titular point about “saving China,” furthermore, underscores the contrast in the perceptions of those inside and outside China with regard to contemporary Chinese art. For Western journalists, the question was invariably one of individualism and freedom against an authoritarian government. For Chinese critics, it was about the power of Chinese people to identify and contextualize themselves. The very issues described and represented by Solomon spoke to the concerns of Chinese critics over the dangers of Western reception and consumption.

Art critics inside China worried that coverage of Political Pop and Cynical Realism to the exclusion of other current tendencies would only serve to confirm the post–Cold War view of China as simply comprising derivative Western styles, cultures, and consumerism. They were concerned that inclusion in the global art world could be accomplished only by acceding to foreign tastes and that a more comprehensive view of the full range of contemporary Chinese art would be precluded. Art critic Lü Peng, as the chief organizer of the 1992 Guangzhou Biennial, had already attempted to remedy the situation. Intent on creating a Chinese art market funded by local entrepreneurs, he had set out to put the power of evaluation—critical and monetary—in the hands of Chinese critics.17See Peggy Wang, “Art Critics as Middlemen: Navigating State and Market in Contemporary Chinese Art, 1980s–1990s,” in Art Journal (Spring 2013): pp. 6–19, and Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market, pp. 219–233.

In 1994 this power dynamic was the subject of Wang Lin’s damning critique “Oliva is Not the Savior of Contemporary Chinese Art.”18Wang Lin, “Oliva is the Not the Savior of Chinese Art,” Dushu no. 10 (1993). Translated in Wu Hung, ed., Contemporary Chinese Art, pp. 366–368. Wang faulted Achille Bonito Oliva, co-curator of the 1993 Venice Biennale, for using a Eurocentric framework to select artworks. He accused Oliva of deliberately choosing ideologically charged works that would present China as a “living fossil of the Cold War.” To combat the desire to seek “approval from a commanding height,” Wang charged Chinese art critics with the responsibility of selecting work that possessed an “experimental spirit and creative spirit based on the logic of Chinese art’s development.” This call to reclaim and establish for themselves the means and measures of success was posed as a direct challenge to Chinese artists’ growing assumption that they needed Western support in order to succeed.

Even after 1993 these same concerns over agency continued to haunt contemporary Chinese art exhibitions abroad. Hou Hanru, writing in the latter half of the 1990s, addressed what he saw as the continued marginalization of Chinese artists within international exhibitions: “Certainly, [the] Chinese avant-garde, especially Political Pop and Cynical Realism, are gaining more and more opportunities to exhibit in the international art world. In the meantime, the artists involved begin to notice that they themselves are being treated as ‘second-rate citizens’ or consumer goods in the ‘international consumer spectacle culture.’”19Hou Hanru, “Somewhere between Utopia and Chaos,” in Another Long March: Chinese Conceptual and Installation Art in the Nineties, ed. Chris Driessen and Heidi von Meirlo (The Netherlands: Fundament Foundation, 1997), p. 91. To Hou, the repeated exposure of Political Pop and Cynical Realism across multiple exhibition and print platforms reaffirmed Western-centric readings of the “other” and signaled a lack of genuine interest in understanding the complexity of Chinese art. The one-dimensional readings of art and politics were like shiny goods with exotic labels, designed to appeal to distant audiences. With reference to Wang Guangyi’s works, David Clarke writes: “Recent Asian art may still largely be recuperated within a Western-centered vision. . . . Asian contemporary art may still be placed as a further temporary novelty for Western palates or viewed as comforting evidence that the non-Western world is becoming more like the West, is learning to speak its (artistic) language.”20David Clarke, “Contemporary Asian Art and Its Western Reception,” in Contemporary Art in Asia: A Critical Reader, ed. Melissa Chiu and Benjamin Genocchio (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2011), p. 155. See also Britta Erickson, “The Reception in the West of Experimental Mainland Chinese Art of the 1990s,” in Reinterpretation: A Decade of Experimental Chinese Art (1990–2000), ed. Wu Hung et al. (Art Media Resources, 2002), pp. 105–112. Writings such as this, on the geopolitical currents surrounding the international reception of contemporary Chinese art, have formed an important subset in both contemporary Chinese art and global art histories.

This scholarly discourse rightfully positions the 1993 exhibitions as a starting point for the problematic reception and Western-centric canonization of contemporary Chinese art. Though it is important to recognize these aspects of the exhibitions, it is also necessary to study them beyond their legacies as purveyors of East-West tensions.

1993: Before the Aftermath

One of the by-products of the attention paid to Political Pop and Cynical Realism was the dominant view that, as art critic Geraldine Norman put it, “Idealism died in China with the victims of Tiananmen Square.”21Geraldine Norman, “Art Market: A Pot of Paint in the Face of Mao,” The Independent (London), December 5, 1993. Though the Tiananmen Square massacre undoubtedly dealt a blow to young intellectuals’ hopes for China, declarations that “idealism died” can too easily reduce all artists’ motivations to narratives of despair, leaving little room to acknowledge their agency and capacity to change. A closer look at the 1990s reveals robust artistic momentum and even idealism, which can, in fact, be detected in the 1993 exhibitions.

To understand how idealism can be associated with this period, it is necessary to see the post-1989 period not merely as depressed and cynical, but also as a time marked by the birth of new artistic approaches. To participants in the Chinese art world, 1989 brought swift and drastic changes. “Post-1989” refers not only to post-Tiananmen, but also to the numerous shutdowns of the China Avant-Garde exhibition during its run at the National Art Gallery in Beijing (now the National Art Museum of China) in February 1989. The government’s closure of the weekly newspaper Fine Arts in China further signaled an end to the drive for cultural enlightenment that had galvanized artists throughout the 1980s.22From the mid- to late 1980s, young artists across the country—often joined together in collectives—set out to achieve grand and lofty goals through art. Informed by both Western theory and traditional Chinese philosophy, artists often discussed artistic production in terms of humanism and liberation. This phenomenon is known as the ’85 Art New Wave. Though on the one hand this fed into the post–June 4 atmosphere of confusion and despondency, on the other hand, it precipitated new pockets of creativity in the art world. Even if tainted by tragedy, styles such as Political Pop and Cynical Realism still showed how a slew of new experiments in form and function took off in the early 1990s. Though artists were no longer driven by the same lofty goals that characterized the 1980s, idealism hadn’t died altogether. Instead, it took on a more critical bent. Political Pop and Cynical Realism were only a small sampling of the multiple kinds of experiments erupting across generations and geographies in China. When seen in a broader context, even these styles can be regarded as part of a surge in new interrogations, experiments, and ways of thinking about contemporary art that were emerging in the Chinese art world.

Attention should be given to the individuals who took up the mantle of organizing exhibitions that recognized and supported these new art forms. In 1993 there were no established procedures for showing contemporary Chinese art outside of China. As such, the exhibition organizers faced tremendous challenges. Though seldom mentioned, it is important to note that many of the figures involved in bringing the 1993 exhibitions to fruition were not professional curators attached to institutions but rather people who had lived in China for a number of years and were, in many instances, art enthusiasts and students of art. Andreas Schmid, Hans van Dijk, and Jochen Noth, the curators of the China Avant-Garde exhibition, had studied in China in the 1980s. They saw the experimental artists as their friends and believed deeply in the originality and spirit of the work they were producing. One of these curators’ key motivations for organizing the exhibition was the urgent belief that such work needed to be shared worldwide for the benefit of the artists and the international public. From today’s perspective, this may seem idealistic or even simplistic, but a sincere belief in exhibiting contemporary Chinese art blossomed against all odds. In the absence of established organizational mechanisms and an art market, the exhibition organizers’ sheer enthusiasm for and commitment to this art should not be underestimated.

Johnson Chang, the owner of Hanart TZ gallery in Hong Kong and the most business-oriented curator of the group, has objected “to any suggestions that the curatorial selection was developed with financial motives in mind.”23Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market, p. 259. In his recollections of China’s New Art, Post-1989, he notes that foreign sponsorship for the exhibition was unattainable because the title’s allusion to 1989 deterred potential benefactors who “wanted to do business with China.”24Johnson Chang, “Exhibition as Site—Extended case study (China 1993)” panel, Sites of Construction: Exhibitions and the making of recent art history in Asia symposium, Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, October 22, 2013. https://aaa.org.hk/en/programmes/programmes/exhibition-as-site-china-1993 Schmid, in recounting the challenges of securing support for China Avant-Garde, cites political sensitivities. The organizers of all the exhibitions faced the additional obstacle of locating channels for shipping works out of China. In many ways, the curators’ successes in organizing their respective exhibitions despite these challenges testifies to their firm commitment to showing the art.

Francesca Dal Lago, who worked in the Italian Embassy in Beijing in the early 1990s, was instrumental in initiating Passage to the East, a special exhibition at the 1993 Venice Biennale. She recalls: “It was clear there was an energy there that was engaging and really special. And the idea was that these people should be made known outside.”25Francesca Dal Lago, “Exhibition as Site—Extended Case Study (China 1993)” panel, October 22, 2013. https://aaa.org.hk/en/programmes/programmes/exhibition-as-site-china-1993

Chang and Schmid both originally envisioned their respective exhibitions as encompassing longer spans of recent history. As each reveals in his recollections of that time, what was happening at that moment on the ground shifted the focus to the present. Chang remembers: “When I went back in 1991, everything had changed. So I changed my mind about bringing the last show to Hong Kong. . . . What was being made was very exciting. A lot of it very secretive, a lot of it was half-baked. What was evident was that this was the dawn of a new era. It was also evident that the 1980s was closed and we were on the dawn of a new period. So the strategy of the Post-1989 exhibition was to define what was different from the 1980s.”26Johnson Chang, “Exhibition as Site—Extended Case Study (China 1993).”

Speaking of his return to China in November 1991 to prepare China Avant-Garde, Schmid relates: “Before autumn 1991, we had the idea to cover the 1980s including No-Name Group and Star Group, but already on this trip we had to face a new and different reality: times had changed and had brought a new generation of very young artists who were different from the 1980s in attitude as well as in artistic manner and style.”27Andreas Schmid, “Exhibition as Site—Extended Case Study (China 1993)” panel, October 22, 2013.

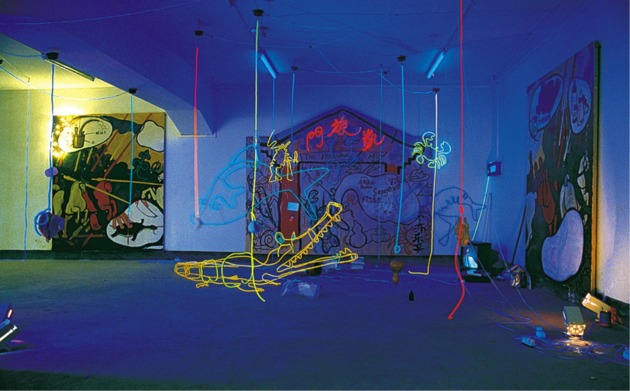

Though he mentions Cynical Realism in particular, Schmid also notes the surprise he experienced when viewing photographs of works by the Big Tail Elephant Group in Guangzhou: “It was very interesting because we thought everything was repressed. But, it was not. This Guangzhou group was so experimental, they used so many media, so we decided to take them in, too.”28Ibid. As a result, Lin Yilin was one of the sixteen artists featured in China Avant-Garde, while the other three members of Big Tail Elephant—Chen Shaoxiong, Liang Juhui, and Xu Tan—were included among the forty-four additional artists featured in the catalogue.

Indeed, the Big Tail Elephant Group is an excellent example not only of new stylistic experiments but also of the new ideas about artistic process that launched them. In their 1993 working meeting, Xu Tan explained: “In this group, every artist’s individual creation is encouraged and supported, and you can feel the liveliness of creativity; it is a place of freedom, such that our collaboration generates a force—a lasting potential. The openness of our working structure is the source of our confidence in the future.”29Lin Yilin, “ Big Tail Elephants: Liang Juihui, Xu Tan, Chen Shaoxiong, and Me,” discussion recorded July 1993, trans. Lina Dann. The sense of zeal and drive can be felt not only in the stylistic differentiation, but also in their forward-looking attitudes toward art and the creative processes of production.

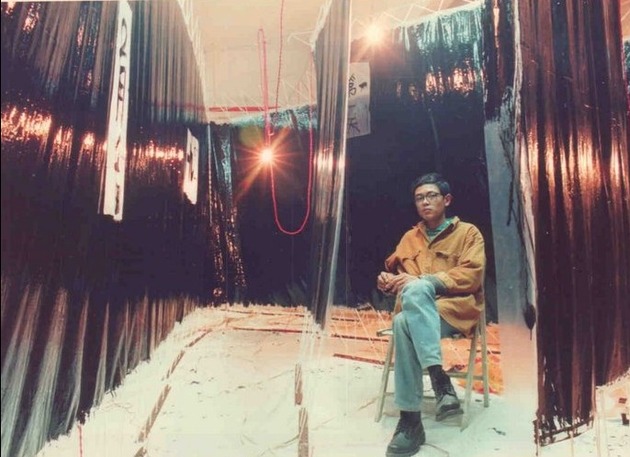

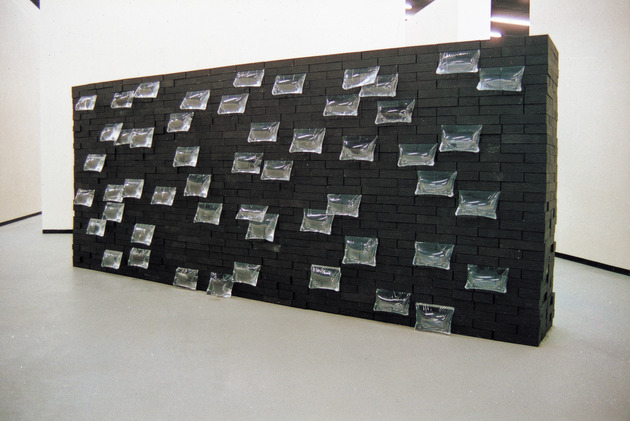

The members of the Big Tail Elephant Group experimented widely with different materials, often in the form of elaborate installations and/or performance. Unlike Political Pop and Cynical Realist painters, they didn’t seek to formulate visual styles on canvas but rather to realize concepts by means of objects and spaces. Though the members of the group worked individually, they supported each other and helped to theorize each other’s work and drive each other’s creativity. In his 1991 performance Seven Days in Silence, Chen Shaoxiong painted a piece of hanging plastic for a week without saying a word. In this action, he attempted to create a situation in which time could be experienced differently from the way it is lived in the usual course of daily existence.30Chen Shaoxiong, interview with the author, July 8, 2011, Beijing, China. Xu Tan also engaged questions of time, particularly in terms of speed and pace, in his installation Uniform Velocity, Variant Velocity (1992). In the dim space of Big Tail Elephant Group’s second exhibition, Xu arranged neon tubing to create a playful, disorderly scene reminiscent of the bright, garish decor of restaurants and entertainment venues in Guangzhou. In addition to presenting colorful neon forms in recognizable shapes, the artist also dangled fluorescent wires from the ceiling and attached to them a range of objects: medicine bottles, syringes, foodstuffs, etc. Hooked up to an electric motor, these long neon strands rotated at different speeds. As Xu described it: “We are entering into a speed of un-adaptable changes, Western culture, traditional culture, commercial, and popular culture, and Socialist thinking.”31“Dialogue between Xu Tan and Shin-Yi Yang,” OCAT Terminal, August 2002. http://www.ocat.org.cn/index.php/Exhibition/?hid=530&hfid=254. Xu’s references to the coexistence of disparate ideologies and his inclusion in his 1992 piece of commercial signs recall important aspects of Political Pop paintings, however, his attention to velocity, repetitive motion, light, and asynchronicity marks a departure from the reliance on visual symbols and graphic composition found in Wang Guangyi’s paintings. The coexistence of these distinct languages and ways of thinking about art showcases the vast range of artistic experiments that were being conducted to communicate and critique contemporary experiences in the early 1990s.

This again points to an important way of thinking about the artistic energy of 1993: it was composed of and produced by a diversity of experiments. It reminds us that at any given time, multiple generations of artists are working at once, drawing upon distinct histories and artistic pasts, and generating a variety of artistic concepts. For example, though Political Pop and Cynical Realism are often mentioned in the same breath, Li Xianting’s observation that most Political Pop artists were born in the 1950s while Cynical Realists emerged from a younger generation, is usually overlooked. In fact, Fang Lijun, positioned his work in contradistinction to the art of Wang Guangyi’s generation, which he regarded as “superficial” and “pivoted on ‘too many motifs, gestures, symbols and narrative illustrations of an idea.’”32Karen Smith, Nine Lives: The Birth of Avant-Garde Art in New China, p. 151. Though Cynical Realists such as Fang Lijun and Liu Wei found fame alongside of the Political Pop artists such as Wang Guangyi and Yu Youhan, they were of a different generation and ultimately drew on their own histories and ideas of what art should be. Their peers included even more artists who were on the brink of developing new concepts and styles. Focusing on 1993 thus serves as a way of thinking about how generations and collective experiences inform staggered and varied trajectories of stylistic and conceptual maturity. This, in turn, allows us to recognize and distinguish among coexisting attitudes, opportunities, and artistic methods.

Conclusions

The 1993 exhibitions offer a valuable window onto the pressing concerns that were then germinating in global and local discourses. I have suggested three ways in which we can approach these exhibitions. First, focusing on the reception of the exhibitions opens up the problematic East-West power relations undergirding the ways in which contemporary Chinese art has been interpreted and canonized. Second, remembering that though 1993 was the year these exhibitions were seen, it was in the preceding years that they were conceived, planned, and fine-tuned. Therefore, when assessing the significance of the exhibitions, it is necessary to attend not only to the concerns over reception that developed in their aftermath, but also to the excitement and curatorial decisions that brought them to fruition. This leads to my third point: that in addition to adopting a wider temporal scope when considering the importance of these exhibitions, we need also to adopt a wider geographical and cultural perspective, to look further than the exhibition checklists and the artists who received the most attention.

Indeed, the examination of these two final points places emphasis on a new sense of energy in the early 1990s, which ultimately brought these exhibitions into being. This dynamism provides a significant counterpoint to the dominant understandings of contemporary Chinese art of the early 1990s that surround the 1993 exhibitions, in particular the notion that idealism had died in China. From the Garage Show in Shanghai (1991) to the New Generation exhibition in Beijing (1991) and the activities of the Big Tail Elephant Group in Guangzhou, the early 1990s witnessed artists of different generations and regions working in diverse modes yet also responding to one another. Regardless of who was exhibited in the 1993 exhibitions, their work came out of a context in which multiple generations—veterans of the ’85 Art New Wave, recent graduates, and artists not yet fully fledged—all contributed to a sense of percolating energy and creativity in the early 1990s.

- 1In January, Johnson Chang and Li Xianting’s exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989 opened in Hong Kong (January 31–February 25, 1993). An abbreviated version of the exhibition traveled later that year to Australia under the title Mao Goes Pop: China Post-1989 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, June 2–August 15, 1993). Andreas Schmid, Hans van Dijk, and Jochen Noth’s exhibition China Avant-garde started at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (January 30–May 1993) and traveled to the Kunsthal Rotterdam (May 29–August 22, 1993), the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (September 4¬–October 24, 1993), and Kunshallen Brandst Klædefabrik, Odense, Denmark (November 12, 1993–February 6, 1994). Silent Energy, co-curated by David Elliot and Lydie Melpham, was shown at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (part 1: June 27–August 29, 1993; part 2: September 5–October 24, 1993). In June 1993, fourteen Chinese artists participated in a special exhibition titled_ Passage to the East_ at the Venice Biennale. Four Chinese artists were featured in the experimental Aperto section of the Biennale, and Chinese critic Kong Chang’an served as a member of the Aperto curatorial team. Two exhibitions were focused specifically on the diaspora: David Elliot and Lydie Mepham’s Silent Energy: New Art from China, held at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, and Gao Minglu and Julia F. Andrews’s Fragmented Memory: The Chinese Avant-Garde in Exile, at the Wexner Art Center in Columbus, Ohio.

- 2In 1978, Deng Xiaoping emerged as the paramount leader of the People’s Republic of China and the Communist Party of China. Although he stepped down as Chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1989, he maintained political influence among the political elite. On his 1992 Southern Tour, Deng—recognized as “the chief architect of China’s reform”—promoted the same reform policy that he had initiated in 1979.

- 3Pablo Lafuente, “Introduction: From the Outside In—‘Magiciens de la Terre’ and Two Histories of Exhibitions,” in Making Art Global (Part 2) (London: Afterall Books, 2013), p. 11.

- 4Rasheed Araeen, “Our Bauhaus others’ Mudhouse,” in Third Text 3, no. 6 (1989), p. 3.

- 5Throughout the 1990s, expatriate art critic and curator Hou Hanru was the most vocal participant in these discourses, particularly when speaking on behalf of diaspora artists. Efforts to expose and challenge the Western-centric global art world continue today. Most notably, the initiative to transform the global art world into multiple art worlds has been championed recently in Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg, and Peter Weibel’s exhibition The Global Contemporary. Art Worlds after 1989 (2011–2012). The accompanying publication, The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds (2013), significantly includes an entry on the 1993 exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989.

- 6Chan Lauk’ung (pen name of Kong Chang’an), “Ten Years of the Chinese Avant-Garde: Waiting for the Curtain to Fall,” Flash Art 25, no. 162 (January/February 1992): pp. 110–114.

- 7Kong Chang’an, “Exhibition as Site—Extended case study (China 1993)” panel, Sites of Construction: Exhibitions and the making of recent art history in Asia symposium, Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, October 22, 2013. http://www.aaa.org.hk/Programme/Details/435. Kong went on to say that, from the time in 1991 when Achille Bonito Oliva and Helena Kontova were appointed co-directors of the Venice Biennale, every issue of Flash Art included an article about the upcoming iteration of this event. The editor of Flash Art, Giancarlo Politi, was Kontova’s husband.

- 8Li Xianting, “Apathy and Deconstruction in Post-’89 Art: Analyzing the Trends of ‘Cynical Realism’ and ‘Political Pop’” Art Trends no. 1 (1992). Translation in Wu Hung, ed., with the assistance of Peggy Wang, Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, (New York: Museum of Modern Art), pp. 157–167.

- 9This is relayed in Li Xianting’s 2000 postscript to the 1992 Art Trends article cited in note 8. Postscript published in Li Xianting, Art is Not the Important Thing _(Jiangsu: Jiangsu Art Publishing, 2000), p. 306. Translation of original essay and postscript in Wu Hung, ed., _Contemporary Chinese Art, cited above in note 8.

- 10Later publicity materials followed suit: in 1997, the exhibition China’s New Art, Post-1989 at the Salina Art Center, Salina, Kansas, featured The Waving Mao as well. Work by Liu Wei, a leading figure in Cynical Realism, was also widely publicized in ads for the exhibition in London.

- 11Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market: Chinese Contemporary Art in the Post-Mao Era (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishing, 2014), p. 268 n 13.

- 12Andreas Schmid, “The Dawn of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West” in Negotiating Difference: Contemporary Chinese Art in the Global Context, ed. Juliane Noth et al. (Weimar: VDG, 2012), p. 294. Franziska Koch studies this exhibition in depth in “‘China’ on Display for European Audiences? The Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art—China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993),” in Transcultural Studies no. 2 (2011): pp. 66–139.

- 13Schmid, “The Dawn of Chinese Contemporary Art in the West,” p. 294.

- 14John Russell Taylor, “Trailblazing East and West,” The Times (UK), March 8, 1993.

- 15Andrew Solomon, “Their Irony, Humor (and Art) Can Save China,” The New York Times Magazine, December 19, 1993, p. 66.

- 16Karen Smith, Nine Lives: The Birth of Avant-Garde Art in New China, updated ed. (China: Timezone 8, 2009), p. 161. All subsequent citations refer to this edition.

- 17See Peggy Wang, “Art Critics as Middlemen: Navigating State and Market in Contemporary Chinese Art, 1980s–1990s,” in Art Journal (Spring 2013): pp. 6–19, and Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market, pp. 219–233.

- 18Wang Lin, “Oliva is the Not the Savior of Chinese Art,” Dushu no. 10 (1993). Translated in Wu Hung, ed., Contemporary Chinese Art, pp. 366–368.

- 19Hou Hanru, “Somewhere between Utopia and Chaos,” in Another Long March: Chinese Conceptual and Installation Art in the Nineties, ed. Chris Driessen and Heidi von Meirlo (The Netherlands: Fundament Foundation, 1997), p. 91.

- 20David Clarke, “Contemporary Asian Art and Its Western Reception,” in Contemporary Art in Asia: A Critical Reader, ed. Melissa Chiu and Benjamin Genocchio (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2011), p. 155. See also Britta Erickson, “The Reception in the West of Experimental Mainland Chinese Art of the 1990s,” in Reinterpretation: A Decade of Experimental Chinese Art (1990–2000), ed. Wu Hung et al. (Art Media Resources, 2002), pp. 105–112.

- 21Geraldine Norman, “Art Market: A Pot of Paint in the Face of Mao,” The Independent (London), December 5, 1993.

- 22From the mid- to late 1980s, young artists across the country—often joined together in collectives—set out to achieve grand and lofty goals through art. Informed by both Western theory and traditional Chinese philosophy, artists often discussed artistic production in terms of humanism and liberation. This phenomenon is known as the ’85 Art New Wave.

- 23Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market, p. 259.

- 24Johnson Chang, “Exhibition as Site—Extended case study (China 1993)” panel, Sites of Construction: Exhibitions and the making of recent art history in Asia symposium, Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, October 22, 2013. https://aaa.org.hk/en/programmes/programmes/exhibition-as-site-china-1993

- 25Francesca Dal Lago, “Exhibition as Site—Extended Case Study (China 1993)” panel, October 22, 2013. https://aaa.org.hk/en/programmes/programmes/exhibition-as-site-china-1993

- 26Johnson Chang, “Exhibition as Site—Extended Case Study (China 1993).”

- 27Andreas Schmid, “Exhibition as Site—Extended Case Study (China 1993)” panel, October 22, 2013.

- 28Ibid.

- 29Lin Yilin, “ Big Tail Elephants: Liang Juihui, Xu Tan, Chen Shaoxiong, and Me,” discussion recorded July 1993, trans. Lina Dann.

- 30Chen Shaoxiong, interview with the author, July 8, 2011, Beijing, China.

- 31“Dialogue between Xu Tan and Shin-Yi Yang,” OCAT Terminal, August 2002. http://www.ocat.org.cn/index.php/Exhibition/?hid=530&hfid=254.

- 32Karen Smith, Nine Lives: The Birth of Avant-Garde Art in New China, p. 151.