Sarah Meister, Curator of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, explores photography’s capacity to represent temporal dislocations during the C-MAP Latin America research group’s trip to Havana, Cuba, in May 2018.

It’s impossible to spend even an hour in Cuba without encountering an intermingling of past and present that feels a bit like looking at a photograph of yourself as a child. The difference is that in Cuba, the past and the present coexist: before you’ve left the airport in Havana, you’ve seen dozens of Cadillacs, like you’d find in Los Angeles on the set of a 1950s movie or in the garage of an avid car collector, functioning as taxis. Photography—almost by definition a representation of then, experienced now—seems an apt medium through which to explore these temporal dislocations.

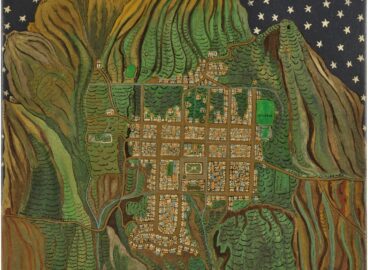

Carlos Garaicoa essentially tangles past and present in work that evokes the persistence of memory and a utopian promise of progress. Through pins and threads affixed to enlargements of abandoned, decaying, or recently demolished buildings, he points to the limitations of a photograph’s ability to capture more than a single moment in time. We first exhibited his work at MoMA in New Photography ’05: Carlos Garaicoa, Bertien van Manen, Phillip Pisciotta, Robin Rhode, acquiring this diptych for the exhibition. Although Garaicoa’s practice is rooted in a close observation of his native Cuba, he has expanded this interest in urban archeology to other cities around the globe. One of our first stops in Havana was Garaicoa’s residency space, Artista x Artista, where we were graciously welcomed by Lillebit Fadraga (Garaicoa wasn’t in town). Even my only cursory newfound appreciation of the city’s suspended architectural condition deepened my admiration for his work.

For several decades, Cristina Vives has been a prominent voice in establishing a framework for understanding photography in Cuba, and José A. Figueroa, her husband, has been a comparably central figure in the field. He worked for many years in the studio of Alberto Korda, one of the photographers Fidel Castro relied upon to document Cuba in the wake of the Revolution. Among other works on view in their street-level exhibition space was a densely packed display of reproductions copied (often surreptitiously) from various archives and agencies that now house the remaining contact sheets and prints from Studios Korda. The images were made between 1954 and 1968: a wall text explained that Studios Korda survived the Revolution “essentially because photography was conceived as a ‘work project’ and not as a ‘product,’” yet on March 14, 1968, the studio was “intervened” and the archives destroyed or dispersed. These scanned enlargements of contact sheets scattered and buried a half a century ago, crowded into a modest display, point to photography’s evidentiary potential as well as the sense of urgency to protect these unsanctioned images from Cuba’s past. Yet this work is not a time capsule, and most of the originals remain scattered between government archives and agencies: the images of contact sheets and photographic prints were made visible—and mediated—by rough, sometimes hastily captured digital scans, enlarged for legibility and without allegiance to their original scale. As a result, viewers grappled with the entanglement of past and present … which is, perhaps, not unlike the cars whose bodies hearken back the 1950s but whose functionality depends on newer engines, tires, and breaks.

It would be irresponsible to reflect on photography in Cuba without at least a brief mention of one of the most frequently reproduced and widely circulated photographs of the twentieth century: Korda’s photograph of Che Guevara.1For an engaging account of the story behind this iconic photograph, see Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo, “The Story behind Che’s Iconic Photo,” Cuba: Smithsonian Journals Travel Quarterly, Smithsonian.com, November 3, 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/smithsonian-journeys-travel-quarterly-cuba-180960694/ I have been thinking quite a bit about another photograph that could make this claim (Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother), and the ways in which both images’ ubiquity is linked to the fact that they were, at least initially, considered to be in the public domain. What this means, in practical terms, is that these images could be printed by anyone at any scale and in any quantity at any time. In Havana, we found Che’s image everywhere, although, my favorite was certainly a poster in the abandoned factory that is now Wilfredo Prieto’s studio. In Vives and Figueroa’s bedroom (yes, they were kind enough to welcome us into their apartment), we found two photographs that amplify this point: one of a Zippo lighter onto which this image has been engraved (if you look closely, you’ll see it was made after 1998, by which time Korda had established his claim to copyright), and another of their bed, on which thirty-two prints of Che’s likeness were neatly arranged. The fact that these photographs were framed and hanging by the same bed pictured seemed like yet another loop in a timeless cycle of reproduction.

I would be equally remiss if I didn’t mention Nelson Ramírez de Arellano Conde and his admirable work at the Fototeca de Cuba, where he has been the director since 2010. Our visit wasn’t long—even a week would have been insufficient to see the 80,000 prints and negatives that constitute their collection—but we enjoyed an exhibition drawn from it, De lo real inanimado (Of the Real Inanimate), which included two works by Liudmila & Nelson.2Somehow, on top of his day job, Ramírez, along with his partner/wife, Liudmila Velasco, manages to sustain an artistic practice: the couple represented Cuba in the 2013 and 2017 Venice Biennales. Ramírez also shared with us their holdings of work by graphic designer and photographer José Manuel Acosta from the early 1930s, and by studio photographer Joaquín Blez, whose work was completely unknown to me before this visit.

The intermingling of past and present in contemporary Cuban art is hardly the exclusive domain of photography. The vitality of this dialogue was evident throughout our unforgettable evening with performance artist Tania Bruguera, curator Abel González Fernández, and the amazing array of artists they gathered to share their work across all media. Other particularly compelling examples we encountered include Juan Carlos Alom’s work (particularly his film Habana Solo), and Fidel Garcia’s data/technology-driven installations, many of which evoke the complex connections between Cuba’s history, its present, and its imagined future.

To conclude, I’d like to consider Leandro Feal, who shares with this author a kindred love of photography. We met Feal during our visit to El Apartamento, where we also had the pleasure of witnessing an intergenerational dialogue between Feal, Yornel Martínez, and Eduardo Ponjuán González, who had taught them both. Feal spoke about several bodies of work and, in particular, the challenge of making unclichéd photographs in a country that has become (in his words) “visually prostituted.” It was easy to understand this pressure, even from my amateur perspective: the brightly colored cars from another era and the buildings that had seen better days are almost irresistibly picturesque.3As much as I wanted to savor every detail, each tap of my iPhone shutter was a reminder that I was capturing only the veneer of a place known to many of us through these postcard views.

One of Feal’s recent works From Reform to Counter-Reformation is comprised of one hundred small prints (5 x 7 or 7 x 5 inches), which are typically adhered directly to the wall in a single row. Made in 2016, the suite of images reflects various manifestations of the improved US-Cuban relations under Barack Obama’s administration: the Rolling Stones performing, The Fate of the Furious (aka Fast & Furious 8) being filmed, Karl Lagerfeld presenting his forthcoming line for Chanel, and Madonna celebrating her fifty-eighth birthday with friends. But Feal also includes images of the hundreds of thousands of Cubans participating in the May Day rally, and comparable numbers mourning the death of Fidel Castro in November, harnessing photography’s ability to construct our understanding of then through the coexistence of disparate moments.

- 1For an engaging account of the story behind this iconic photograph, see Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo, “The Story behind Che’s Iconic Photo,” Cuba: Smithsonian Journals Travel Quarterly, Smithsonian.com, November 3, 2016, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/smithsonian-journeys-travel-quarterly-cuba-180960694/

- 2Somehow, on top of his day job, Ramírez, along with his partner/wife, Liudmila Velasco, manages to sustain an artistic practice: the couple represented Cuba in the 2013 and 2017 Venice Biennales.

- 3As much as I wanted to savor every detail, each tap of my iPhone shutter was a reminder that I was capturing only the veneer of a place known to many of us through these postcard views.