In this text, Fernando Bruno analyzes the particular relationship between painting and writing in the work of Argentine artist Mirtha Dermisache, examining the specific ways in which it contrasts with some of the most significant artistic tendencies at the end of the sixties and seventies in Argentina.

Read the Spanish version here.

In the Argentine context of the late sixties and early seventies, Mirtha Dermisache (1940–2012) is an exceptional artist whose work allows us to rethink, from new angles, the relationship between painting and writing, and the transformations that occurred in connection with the emergence of mass-media art and conceptualism in a broad sense. Dermisache was in touch with the most important discussions, artists, and institutions of the time, yet her work doesn’t completely fit in with the main trends established during those years.1Although she was not one of the main figures in Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Dermisache participated in many of its activities. For instance, within the framework of the Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales (CLAEM), which was part of the institute, she worked on a project to turn her graphisms into sounds, alongside Fernando von Reichenbach and other composers. She was also connected to the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC) [Center for Art and Communication] and to the Grupo de los Trece in their beginnings, and participated in several of their collective exhibitions. In a time marked by the linguistic turn in the humanities and the consolidation of the hegemony of mass media, Dermisache worked at the limits of communication as such. In this brief article, I will examine the way Dermisache’s work connects with some tendencies in Argentine art, comparing, on the one hand, her “illegible writings” to León Ferrari’s “deformed writings” and legible calligraphies, and, on the other, her intervention in the established formats of print media to the ways mass-media artists made use of them.

At first glance, Dermisache’s books could be considered within the artist’s book trend that began to proliferate simultaneously in different parts of the world—Latin America included—as one of the manifestations of the growing political activism in civil society, and of the formal and stylistic experimentation that inundated the art world. Being relatively inexpensive to produce and easy to circulate, artist’s books were seen as a means of reaching a mass audience beyond the museum and art gallery circles. Artist’s books question the parameters of the art market as well as the conventions of the publishing industry, insofar as they shape new and complex systems of signs that do not conform to established reading patterns.2For an overview of the boom of artist’s books in the seventies, see Joan Lyons, “Introduction,” and Lucy Lippard, “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” in Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook (Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1985). In the Latin American context, artists such as León Ferrari, Ulises Carrión, Leandro Katz, Cecilia Vicuña, and Edgardo Antonio Vigo, among others, worked on various types of publications in the same years as Dermisache. These characteristics are reflected, at least partially, in the works of Dermisache, who championed formal experimentation and the circulation of her work outside traditional circuits. Her books, however, contain certain specific features—some connected to her very personal style, such as her work with illegible writings, and others connected to the Argentine context, such as the expansion of mass-media art—which separate them from the imagery commonly associated with artist’s books.

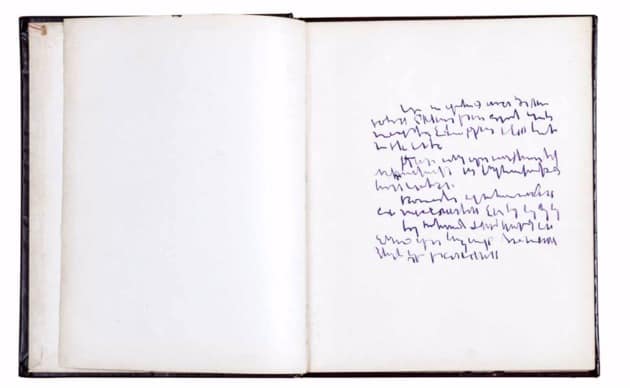

Dermisache produced her two first books in 1967. They were originally conceived of as a single volume of five hundred pages that was, for practical reasons, divided into separate books. Let us consider, for the purpose of this analysis, the first of those books, simply called Libro N°1 (Book No. 1).3As of that moment, Dermisache would consecutively number the different editions of her books, beginning each year with 1. In general, this looks like a standard book: its size and binding suggest an easily identifiable and extremely familiar object. However, the absence of a title or any reference to the author on the cover captures our attention. When we open the volume, that slight hint of something unusual gives way to a deep strangeness. There are no credits or index; there are no chapters, no texts, no photographs, and no illustrations in the traditional sense—just a blank first page, and then a long series of asemic writings that take up the entire book and do not appear to have any formal or stylistic coherence. Some pages have the formal structure of writing, including lines, paragraphs, ends of lines, and spacing. Other pages lack those elements and instead resemble free drawing, with marks forming in some cases circular structures; while still others are vertically or diagonally oriented, or are totally abstract and irregular. Sometimes the marks take up a limited space and sometimes they take up the entire page. The colors of the graphic symbols vary and do not appear to follow any recognizable pattern. These signs “move away from writing,” and yet they “refuse to move closer to visual art.”4Edgardo Cozarinsky, “Un grado cero de la escritura” [“A zero degree of writing”], Panorama 7, no. 156 (April 21, 1970): 51. In that undefined, in-between space, it is the viewer who, attempting to create meaning out of the multiplicity of possibilities, must complete the work.

Dermisache worked on these graphic symbols for several years, and it was the French philosopher and critic Roland Barthes who, in 1971, conceptualized them as “illegible writings,” a designation that would become canonical for any description of Dermisache’s work.5Dermisache had contacted Barthes through Argentine filmmaker Hugo Santiago, director of the now-legendary film Invasión (1969), who had taken one of her books to Paris. That year, Barthes sent the artist an affectionate letter in which he wrote: “I will only say how struck I am not only by the remarkable quality of your lines (and that is not a secondary question), but also—indeed mostly —by the extreme intelligence of the theoretical problems around writing that your work tackles. You have managed to produce a certain number of forms that are neither figurative nor abstract, forms that could be called illegible writing, which leads readers to formulate something that is neither a specific message nor a contingent form of expression, but, rather, the idea, the essence, of writing.”6Roland Barthes to Mirtha Dermisache, March 28, 1971, in Mirtha Dermisache. Porque ¡yo escribo! [Mirta Dermisache: because I write!], ed. Agustín Pérez Rubio, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Malba and Fundación Espigas, 2017), 263. The Archivo Mirtha Dermisache (AMD) registers nine letters sent to Dermisache by Barthes between 1971 and 1974. Some are handwritten and some are typewritten; most deal with bureaucratic issues related to recommendations and specific requests. This letter, in particular, is the one that most accurately reflects the French critic’s interest, and served as the basis for a short text that, written by Barthes in 1973, was to serve as an introduction to Dermisache’s work.“From then on,” Dermisache said retrospectively, “I understood what I was doing. It was as if he had explained to me what it was I was doing.”7Annalisa Rimmaudo and Giulia Lamoni, “Entrevista a Mirtha Dermisache” [Interview with Mirtha Dermisache], inMirtha Dermisache. Publicaciones y dispositivos editoriales [Mirtha Dermisache: Publications and editorial devices], exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Pabellón de las Bellas Artes de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, 2011), http://hipermedula.org/2017/08/entrevista-a-mirtha-dermisache/.

In his 1973 essay, “Variations sur l’écriture” (Variations in Writing), Barthes develops ideas that could serve to help better understand the Argentine artist’s work. He argues that the true nature of writing is not in its functionality or its effective communication, and to do so he draws on the work of artists such as the Surrealist painter André Masson and Dermisache. He says, “There are also writings that we cannot understand, and yet, we cannot say they are indecipherable, because they simply are beyond decipherment: those are the fictitious writings that certain painters or certain subjects imagine.”8Roland Barthes, “Variations sur l’écriture” [Variations in writing], in Oeuvres complètes [Complete works], vol. 2, 1966–1973 (Paris: Éd. du Seuil, DL, 1994). The history of Chinese calligraphy is, to him, an example of this point: writing was first aesthetic and ritual (it could be used to address the gods), and only after that functional (as a tool of communication and record keeping): “The communication function, which our linguists transform into an answer to everything, is subsequent, derivative, secondary.” Barthes explains that illegibility is not a “dispirited” or “monstrous” state of writing, but rather its true nature, “the essence of a practice perhaps at its extreme and not its center,” and he goes on to claim that illegible writings “tell us (only) that there are signs, but not sense.”9Ibid., 91, 105. Indeed, the language proposed by Dermisache denies intention, utility, and function, and turns in on itself in search of new forms. On the one hand, her graphisms question the idea that a message can be unequivocally expressed and received; on the other, they question the agreement between meaning and signifier, between words and things. And in this dual movement, they challenge the possibility of communication itself, and its limits.

Working at the limits between writing and painting in the Argentine context, however, is not exclusive to Dermisache. León Ferrari’s drawings in the early sixties had already opened a field for reflection on language and what is expressible. Ferrari began his career making small sculptures and ceramics, but then, within a few years, his development took him from tridimensional abstraction to “deformed writings,” and from those to illegible calligraphies.10Luis Pérez-Oramas says: “It is interesting to note that this progression began with abstraction—abstract drawings—and ended with writing—written drawings. At some point, Ferrari commented on this logic, as if within it he had inverted a modern order according to which writing would be abstracted—as in the work of Antonin Artaud and Henri Michaux—into a calligraphy that is illegible, indescribable.” See León Ferrari y Mira Schendel: Tangled Alphabets (New York: The Museum of Modern Art; São Paulo, Brazil: Cosac Naify, 2009), 23. This process, in which painting becomes words, reached its peak in 1964’s Cuadro escrito (Written Painting), a key piece in his career. The title itself announces the transformation of pictorial language into written language. Yet some of its characteristics separate Ferrari’s work from Dermisache’s. In her case, there is no such transition toward legibility: each of her writings—the pages in her books, her letters, her mathematical formulae—while maintaining highly different styles and graphic qualities among themselves, is an experiment that would be difficult to repeat, that is far from linguistic understanding.11Except for some loose papers that present her own handwriting in a clearly legible way, which she kept but never considered “work.” Ferrari’s titles are descriptive—and so point to a meaning—while Dermisache’s titles are merely ordinal and provide no reference to content; we could even say that where Ferrari writes a painting, Dermisache paints a writing. Finally, Dermisache did not want to exhibit her graphic symbols separately like “paintings,” she wanted to incorporate them into a publishing and distribution system, which opens another range of problems related to information and communication devices, especially regarding the circulation of works, the attack on the idea of the original, and the museum as a privileged exhibition space.

Dermisache went deep into this research on media, working with a series of recognizable typologies: newspapers, letters, postcards, fragments of stories, comic strips. Diario 1 Año 1 (Newspaper 1 Year 1), from 1972, synthesizes her search, since it resumes the structure of a complex publication—a large-circulation newspaper—that includes a great number of different typologies.12Diario 1 Año 1 (Newspaper 1 year 1) was published by the CAyC in September 1972 for the Arte de sistemas IIexhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. There would be different editions in the following years, with slight variations in content and structure. One 1975 edition, published by Guy Schraenen, is held in the MoMA Library. See Schraenen, “A Transatlantic ‘Affair’,” and Cintia Mezza, Cecilia Iida, and Ana Raviña, biographical chronicle, “Mirtha Dermisache, Life and Work 1940–2012,” in Mirtha Dermisache. Porque ¡yo escribo!, 33–48, 255–90. Ink densities and varying type size allow the easy identification of each typology. As with herCartas (Letters), Dermisache meticulously respected the disposition of all the elements on the page—the grids, columns, titles, leads, and highlights—while completely subverting the probable textual and photographic contents. As with the rest of her production, she carried out “a disassembling operation of the medium,”13The expression belongs to Argentine writer Héctor Libertella, who examined Dermisache’s work: “Dermisache creates perfect newspapers where she draws like a memory a front page, a comic strip section, an editorial, a thick page—or a page of thick strokes—for the violent crime news, a black obituary. Starting from a given written communication event, she empties the classical expectations of the recipient through a disassembling operation of the medium.” Héctor Libertella, Ensayos o pruebas sobre una red hermética [Essays or evidence on a hermetic net]. (Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano, 1990), 23–24. so that its content—the “news”—is illegible.

Artistic experimentation with mass media was a primary focus in the Argentine scene during those years. In the 1966 text “Un arte de los medios de comunicación (manifiesto)” (“An Art of Communications Media [manifesto]”), Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escari, and Roberto Jacoby focused their proposal for a new art on thetransmission of information. Unlike Pop artists, who drew on elements and techniques from the mass media and incorporated them into their work, these artists aimed to build their work “inside” the media. They conceived of their work as a complex process, from its production (real or invented) to its circulation. The new art thus took hold as a critique of mass media’s powers of manipulation rather than as a celebration of its expressive capabilities.14In “Against the Happening” (1967), Roberto Jacoby says, “We are well aware that mass media are essential to control a society and they are therefore manipulated—not less than was writing, in other times—by those now in power.” Roberto Jacoby, “Against the Happening,” in Listen, Here, Now!: Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, ed. Inés Katzenstein (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 237–42. Driven by the political and economic situation, especially after Juan Carlos Onganía’s coup,15On June 28, 1966, there was a coup d’état against constitutional president Arturo Umberto Illia, led by Juan Carlos Onganía, the general who would be the de facto president until 1970. Onganía dissolved political parties, took control of national universities, and encouraged military repression in the provinces. From an economic point of view, the dictatorship was characterized by the redistribution of income in favor of the most concentrated sectors or those related to foreign capital. avant-garde artists sought to blur the boundaries between the aesthetic and political spheres, and became radicalized, as evidenced in the paradigmatic collective workTucumán Arde (Tucumán is Burning), in which, along with many others, both Ferrari and Jacoby took part.16Tucumán Arde [Tucumán is Burning] was a project executed by a group of artists in November 1968 based on their research work about the exploitative conditions of the people and the concentration of capital in northern Argentina. It consisted of field records, an exhibition held in the headquarters of the confederations of labor unions in Buenos Aires and Rosario, and various actions of publicity and dissemination. This radicalization found a privileged means of expression in the revolutionary use of information channels. Tucumán Arde was explicitly presented as “the creation of a super-informative circuit in order to show the underhanded distortions that the events in Tucuman suffered in the information and broadcast media controlled by the official powers and the bourgeoisie.”17See Inés Katzenstein, “An Art of Communications Media (manifesto),” in Listen, Here, Now!: Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, 231–32.

Like the artists identified with mass-media art, Dermisache worked with the established formats of print media and put the circulation of works at the center of the artistic process, but she did so from a very different perspective, a much more solitary and intimate one. While mass-media artists were concerned with the dematerialization of the artistic object and the thematization of the media as media, not as support of other content outside itself, Dermisache saw in the formal structure of newspapers, comic strips, and letters a chance to expand her expressive field and to explore new possibilities for her calligraphic lines. On the other hand, far from experiences such as Tucumán Arde, in general Dermisache refused to consider the political implications of her work. In an interview published in 2011, she claimed: “The only time I made reference to the political situation in my country in my work was in Diario: the column on the left on the last page alludes to those killed in Trelew. That was in 1972. Except for that massacre, which affected me—and many others—a great deal, I never wanted my work to be read in political terms. What I was doing, and still do, is develop graphic ideas on writing which, in the end, have little to do with political events but much to do with the structures and forms of language.”18Rimmaudo and Lamoni, “Entrevista a Mirtha Dermisache,” 15. The Masacre de Trelew [Trelew massacre] was an act of clandestine repression that anticipated state terrorism in Argentina. On August 15, 1972, twenty-five political prisoners escaped from a prison in Rawson, Chubut Province. Six of them managed to flee to Chile, and the remaining nineteen surrendered and were arrested at the Trelew airport. From there, they were taken to an air force base, where, six days later, they were murdered by members of the navy. Three of the militants managed to survive, although they were severely wounded. However, some of her practices regarding the formal aspects of writing on the margins of painting can hardly be read from a critical perspective without referring to the context of repression and political violence in which they were produced. This is the case with, among others, Diario 1 (Newspaper 1) and Fragmento de historia (Fragment of a Story), from 1974, in which many of the lines lose their color and their calligraphic quality, and become cross-outs, erasures, or plain blocks of black ink that call to mind—consciously or unconsciously—censorship and the impossibility of expression.19It is worth mentioning that during the last civic-military dictatorship (1976–83), Dermisache put aside somewhat her production of new writing in order to devote more time to teaching, which she did following her own method of artistic experimentation. Both in the Taller de Acciones Creativas (TAC) [Creative actions workshop] and in the Jornadas del Color y de la Forma [Intensive work sessions in color and form], she sought to generate spaces for free expression and then to foster the creation of a sort of collective work that, developing over time, would bring together the participants’ various pieces. In her article “Las Jornadas del Color y de la Forma (1975– 1981). El arte como praxis vital” (Intensive work sessions in color and form (1975–1981): art as vital praxis), Lucía Cañada thoroughly describes the dynamics of the Jornadas and their context, and claims that their organization represented a space of freedom at a time when bodies and ideas were being disciplined and controlled: “In a context of greater and greater individualism, of betrayal, and of mistrust of the other, Dermisache formulated a collective proposal where people could sit down together, work with or next to someone else, further that person’s work and make it one’s own, or leave it be knowing that someone else would pick up on it. Dermisache extended an invitation to conceive creative actions, to play with color, to connect to a vital praxis. That was her greatest political act, her bold wager, her avant-garde gesture.” SeeMirtha Dermisache. Porque ¡yo escribo!, 49–63.

Dermisache’s work thus gives shape to a complex universe in which a range of issues cross, connected both to conceptual and timeless philosophical questions (the aesthetical dimension of communication, the dynamics between the expressible and the inexpressible), and to the mentioned historical determinations specific to the local context. Her visual work represents an extremely personal project that allows us to rethink, from new angles, the prevailing trends in the Argentine art scene during those years. At the time of the expansion of research into the dematerialization of the artistic object, Dermisache obsessively focused on the manual production of calligraphic pieces. And, going against the trends of the time, she persisted with her “writing” as a means of reflecting, from a visual arts perspective, on the very essence of language.

Translated from Spanish by Silvina López Medin.

- 1Although she was not one of the main figures in Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Dermisache participated in many of its activities. For instance, within the framework of the Centro Latinoamericano de Altos Estudios Musicales (CLAEM), which was part of the institute, she worked on a project to turn her graphisms into sounds, alongside Fernando von Reichenbach and other composers. She was also connected to the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC) [Center for Art and Communication] and to the Grupo de los Trece in their beginnings, and participated in several of their collective exhibitions.

- 2For an overview of the boom of artist’s books in the seventies, see Joan Lyons, “Introduction,” and Lucy Lippard, “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” in Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook (Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1985). In the Latin American context, artists such as León Ferrari, Ulises Carrión, Leandro Katz, Cecilia Vicuña, and Edgardo Antonio Vigo, among others, worked on various types of publications in the same years as Dermisache.

- 3As of that moment, Dermisache would consecutively number the different editions of her books, beginning each year with 1.

- 4Edgardo Cozarinsky, “Un grado cero de la escritura” [“A zero degree of writing”], Panorama 7, no. 156 (April 21, 1970): 51.

- 5Dermisache had contacted Barthes through Argentine filmmaker Hugo Santiago, director of the now-legendary film Invasión (1969), who had taken one of her books to Paris.

- 6Roland Barthes to Mirtha Dermisache, March 28, 1971, in Mirtha Dermisache. Porque ¡yo escribo! [Mirta Dermisache: because I write!], ed. Agustín Pérez Rubio, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Malba and Fundación Espigas, 2017), 263. The Archivo Mirtha Dermisache (AMD) registers nine letters sent to Dermisache by Barthes between 1971 and 1974. Some are handwritten and some are typewritten; most deal with bureaucratic issues related to recommendations and specific requests. This letter, in particular, is the one that most accurately reflects the French critic’s interest, and served as the basis for a short text that, written by Barthes in 1973, was to serve as an introduction to Dermisache’s work.

- 7Annalisa Rimmaudo and Giulia Lamoni, “Entrevista a Mirtha Dermisache” [Interview with Mirtha Dermisache], inMirtha Dermisache. Publicaciones y dispositivos editoriales [Mirtha Dermisache: Publications and editorial devices], exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Pabellón de las Bellas Artes de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, 2011), http://hipermedula.org/2017/08/entrevista-a-mirtha-dermisache/.

- 8Roland Barthes, “Variations sur l’écriture” [Variations in writing], in Oeuvres complètes [Complete works], vol. 2, 1966–1973 (Paris: Éd. du Seuil, DL, 1994).

- 9Ibid., 91, 105.

- 10Luis Pérez-Oramas says: “It is interesting to note that this progression began with abstraction—abstract drawings—and ended with writing—written drawings. At some point, Ferrari commented on this logic, as if within it he had inverted a modern order according to which writing would be abstracted—as in the work of Antonin Artaud and Henri Michaux—into a calligraphy that is illegible, indescribable.” See León Ferrari y Mira Schendel: Tangled Alphabets (New York: The Museum of Modern Art; São Paulo, Brazil: Cosac Naify, 2009), 23.

- 11Except for some loose papers that present her own handwriting in a clearly legible way, which she kept but never considered “work.”

- 12Diario 1 Año 1 (Newspaper 1 year 1) was published by the CAyC in September 1972 for the Arte de sistemas IIexhibition at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. There would be different editions in the following years, with slight variations in content and structure. One 1975 edition, published by Guy Schraenen, is held in the MoMA Library. See Schraenen, “A Transatlantic ‘Affair’,” and Cintia Mezza, Cecilia Iida, and Ana Raviña, biographical chronicle, “Mirtha Dermisache, Life and Work 1940–2012,” in Mirtha Dermisache. Porque ¡yo escribo!, 33–48, 255–90.

- 13The expression belongs to Argentine writer Héctor Libertella, who examined Dermisache’s work: “Dermisache creates perfect newspapers where she draws like a memory a front page, a comic strip section, an editorial, a thick page—or a page of thick strokes—for the violent crime news, a black obituary. Starting from a given written communication event, she empties the classical expectations of the recipient through a disassembling operation of the medium.” Héctor Libertella, Ensayos o pruebas sobre una red hermética [Essays or evidence on a hermetic net]. (Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano, 1990), 23–24.

- 14In “Against the Happening” (1967), Roberto Jacoby says, “We are well aware that mass media are essential to control a society and they are therefore manipulated—not less than was writing, in other times—by those now in power.” Roberto Jacoby, “Against the Happening,” in Listen, Here, Now!: Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, ed. Inés Katzenstein (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 237–42.

- 15On June 28, 1966, there was a coup d’état against constitutional president Arturo Umberto Illia, led by Juan Carlos Onganía, the general who would be the de facto president until 1970. Onganía dissolved political parties, took control of national universities, and encouraged military repression in the provinces. From an economic point of view, the dictatorship was characterized by the redistribution of income in favor of the most concentrated sectors or those related to foreign capital.

- 16Tucumán Arde [Tucumán is Burning] was a project executed by a group of artists in November 1968 based on their research work about the exploitative conditions of the people and the concentration of capital in northern Argentina. It consisted of field records, an exhibition held in the headquarters of the confederations of labor unions in Buenos Aires and Rosario, and various actions of publicity and dissemination.

- 17See Inés Katzenstein, “An Art of Communications Media (manifesto),” in Listen, Here, Now!: Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, 231–32.

- 18Rimmaudo and Lamoni, “Entrevista a Mirtha Dermisache,” 15. The Masacre de Trelew [Trelew massacre] was an act of clandestine repression that anticipated state terrorism in Argentina. On August 15, 1972, twenty-five political prisoners escaped from a prison in Rawson, Chubut Province. Six of them managed to flee to Chile, and the remaining nineteen surrendered and were arrested at the Trelew airport. From there, they were taken to an air force base, where, six days later, they were murdered by members of the navy. Three of the militants managed to survive, although they were severely wounded.

- 19It is worth mentioning that during the last civic-military dictatorship (1976–83), Dermisache put aside somewhat her production of new writing in order to devote more time to teaching, which she did following her own method of artistic experimentation. Both in the Taller de Acciones Creativas (TAC) [Creative actions workshop] and in the Jornadas del Color y de la Forma [Intensive work sessions in color and form], she sought to generate spaces for free expression and then to foster the creation of a sort of collective work that, developing over time, would bring together the participants’ various pieces. In her article “Las Jornadas del Color y de la Forma (1975– 1981). El arte como praxis vital” (Intensive work sessions in color and form (1975–1981): art as vital praxis), Lucía Cañada thoroughly describes the dynamics of the Jornadas and their context, and claims that their organization represented a space of freedom at a time when bodies and ideas were being disciplined and controlled: “In a context of greater and greater individualism, of betrayal, and of mistrust of the other, Dermisache formulated a collective proposal where people could sit down together, work with or next to someone else, further that person’s work and make it one’s own, or leave it be knowing that someone else would pick up on it. Dermisache extended an invitation to conceive creative actions, to play with color, to connect to a vital praxis. That was her greatest political act, her bold wager, her avant-garde gesture.” SeeMirtha Dermisache. Porque ¡yo escribo!, 49–63.