One of the many intercontinental relationships to arise from Fluxus in the second half of the 1960s was the one between Milan Knížák and Ken Friedman, the two directors of Fluxus East and Fluxus West, respectively.

When, in the 1980s, Dick Higgins and Ken Friedman outlined the basic ideas of Fluxus,1Dick Higgins, “Fluxus: Theory and Reception,” in The Fluxus Reader, ed. Ken Friedman (Chichester: Academy Editions, 1998), 224, and Ken Friedman, “Fluxus and Company,” in The Fluxus Reader, 244. Higgins placed internationalism first and Friedman, globalism. In the twenty years since Fluxus had emerged during the first half of the 1960s—at the height of the Cold War—artists associated with the movement had been willfully flouting borders of all kinds. The poets, visual artists, and musicians gathered around Fluxus coordinator George Maciunas were engaged in a wide range of activities, and they hailed from many countries. Promoting communication among them, and among all people in general, became one of Fluxus’s main missions. Maciunas’s correspondence network and Nam June Paik’s vision of global telecommunications bridges not only grew out of utopian ideas for worldwide democracy, but also reflected the practical needs of a movement that refused to respect the existing divisions of the world.

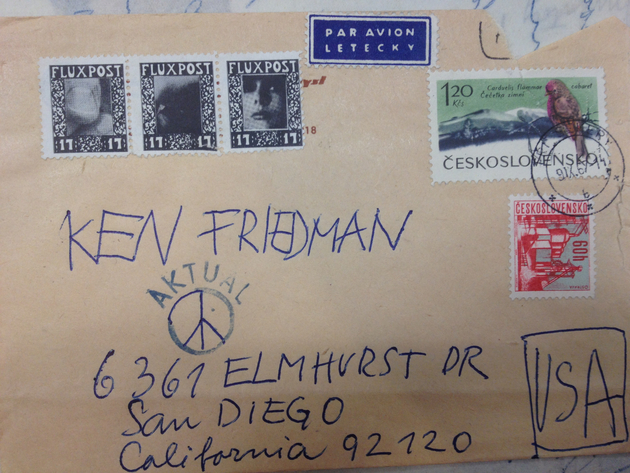

One of the many intercontinental relationships to arise from Fluxus in the second half of the 1960s was the one between Milan Knížák and Ken Friedman, the two of whom Maciunas had appointed as directors of Fluxus East and Fluxus West, respectively. Knížák lived in Czechoslovakia, a satellite of the Soviet Union, and Friedman in California. Although the two men were separated by the Iron Curtain and spoke different languages, they found a common vocabulary almost immediately. And although their dialogue was hardly an example of unfettered global communication, the constraints imposed by physical distance and political circumstance only seemed to strengthen their ties.

Art was the principal concern of neither of them. Like many young people in the 1960s, they felt the need for an antiauthoritarian change in society, one that would foster a new universal consciousness and admit countercultural values as well as sexual liberation. Many Fluxus artists felt that art should be dissolved in life. In Knížák and Friedman’s correspondence, life itself is revealed as a form of art, open to change, flower-power ideals, and, above all, love.

Directors of East and West

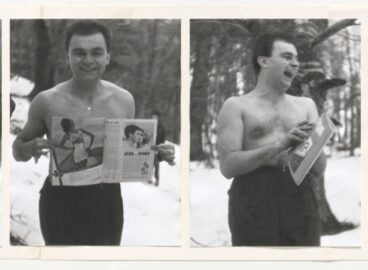

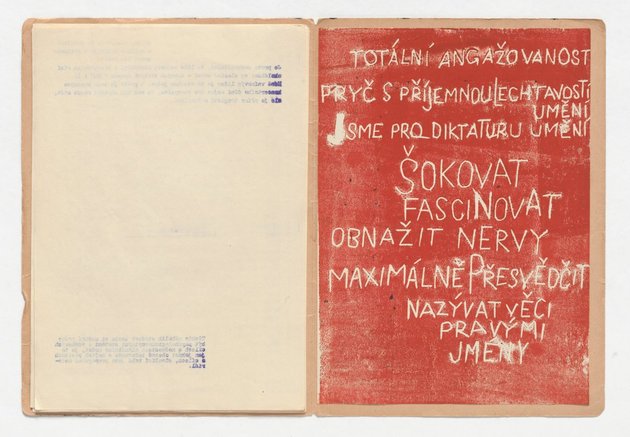

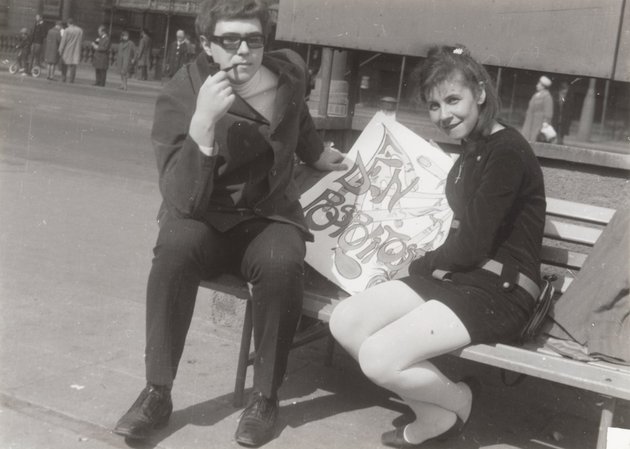

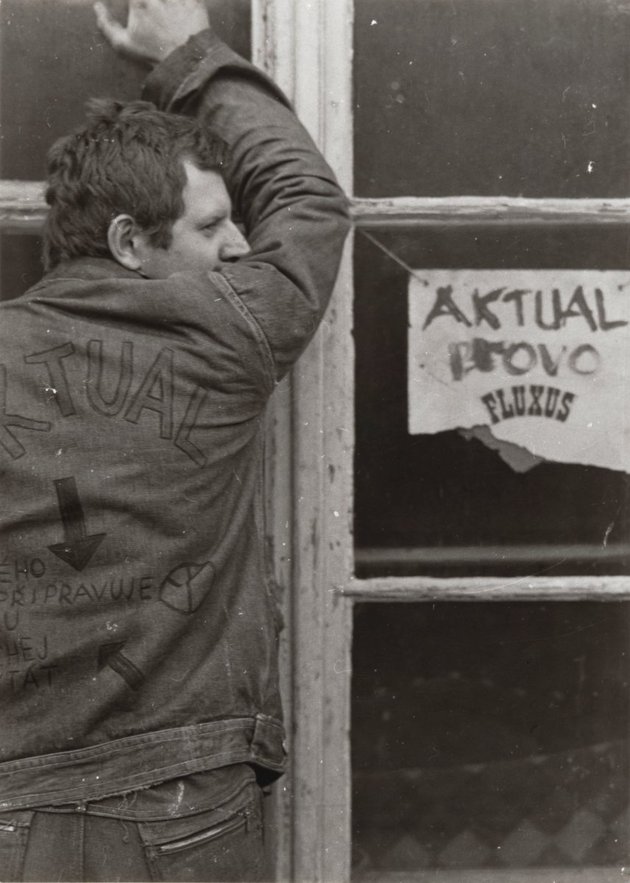

A pioneer of action art, Knížák worked outside Czechoslovakia’s established art community. He abandoned traditional art in the mid-1960s and began engaging in radical social activities whose aim was to reform life itself. In 1964 he founded Aktual Art, an association of nonconformists who organized playful street actions and participated in projects that were later identified as mail art. Some of its members experimented with drugs. Most outsiders took the group for a cohort of long-haired hooligans with a penchant for playing pranks and creating disturbances.

In 1965 Aktual dropped “art” from its name and published a samizdat magazine filled with social manifestos and utopian declarations. The members showed no desire to join the established avant-garde and criticized the concept of art as such, asserting that art should become a part of life, a pursuit aimed at “living otherwise.” In late 1965 or early 1966 Knížák began corresponding with Maciunas.

It was in 1965 that Friedman first came into contact with Fluxus and Maciunas. Friedman was only sixteen at the time, but he quickly found his place among Fluxus artists. He spent most of the years discussed in this essay as a student at San Francisco State University or living with his parents in San Diego, all the while developing and expanding his artistic activities.

As the respective directors of Fluxus East and Fluxus West, Knížák and Friedman operated on the peripheries not only in the geographical sense but also in terms of the kinds of activities they engaged in. For although both considered Fluxus important, particularly when it came to expanding their personal networks, the movement was just one of many outlets for their endeavors. In addition to their Fluxus projects and contacts, both artists, but especially Knížák, pursued independent activities. For Knížák, Fluxus represented an international gateway, and yet he repeatedly criticized the movement for being overly focused on art. He was far more interested in projects with a direct social thrust, ones oriented toward developing new types of interpersonal relations, communities, and togetherness.2Friedman emphasized this idea in later years as well. For example, a Keeping Together Manifestation organized by Friedman in 1971 was described in a university newspaper as a disorganized bacchanalia of building, giving, and receiving. The article quotes Friedman as saying that KTMs are a tool for changing social behavior. Geoffrey Anderson, “Aktual Art Is Just Part of the KTM,” San Diego Daily Aztec (April 16, 1971).

Even before coming into contact with Fluxus and Friedman, Knížák had been using postal communications to address the public. By 1965 he was sending out large numbers of letters under the name of Aktual, sometimes choosing the addressees at random. The missives resembled chain letters whose goal was to create communities of letter writers. At about the same time, Knížák developed the concept of Keeping Together Manifestations (KTMs). He hoped to promote global togetherness through written correspondence and by organizing synchronized actions all over the world.

Love

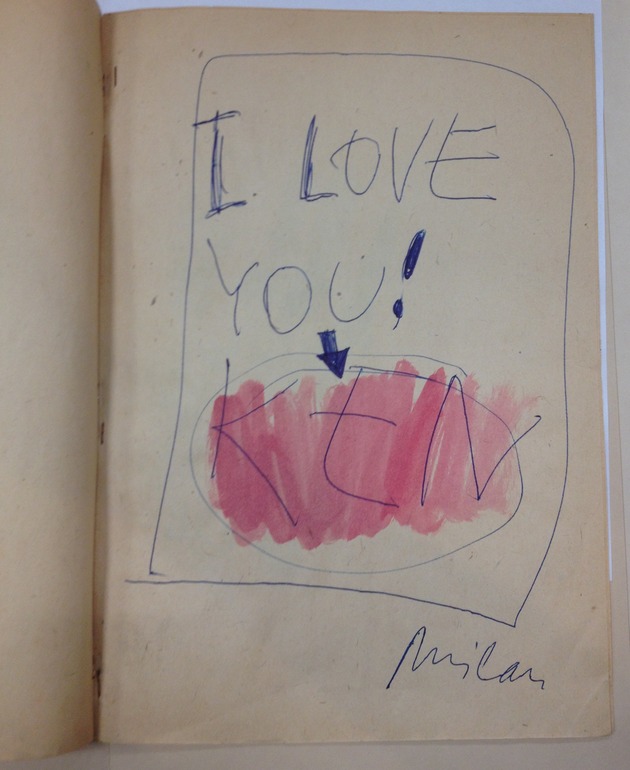

Friedman and Knížák began to write to each other toward the end of 1966 or early 1967.3Letters are not dated, the earliest surviving date mentioned in them is March 1, 1967. The year 1967 is given also in Marian Mazzone, “‘Keeping together’ Prague and San Francisco: Networking in 1960s Art,” in Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research 7, no. 3 (2009): 285. Their correspondence has a passionate character not found in the letters Knížák exchanged with Maciunas and Higgins, although these, too, convey the euphoria of kindred spirits who, independently of one another, had arrived at similar ways of thinking. At this time, all of Knížák’s letters to his friends in the U.S. were signed “Love, Milan,” but the epistolary exchanges between Knížák and Friedman were ardent and visually wild even when it came to practical matters such as coordinating joint activities. Especially in the letters from the spring of 1967, the cadence and tone of their letters are comparable to those of impetuous lovers. The writers’ eagerness to communicate was often frustrated by the speed of the postal service, with each losing track of what he had already written to or sent the other. The letters constantly repeat the same questions: “Did you get my letter?” and “Why haven’t you responded?” At the time of this feverish exchange, Knížák was twenty-seven and Friedman barely eighteen.

The letters Friedman received from Prague were from a foreign and yet in many ways familiar world, and they were not from Knížák alone. In one letter, twenty-one-year-old Aktual member Soňa Švecová, Knižák’s partner at the time, introduced herself as someone for whom life was more important than art. She sent out anonymous letters and packages and staged performance pieces on trams and in public spaces, never documenting her projects because she didn’t consider them important. She pasted playful photographs of herself all over her letter to Friedman and closed with the words, “Write to us something about you!”4Letter from Švecová to Friedman. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 709. The flirtatious pen pals even developed a form of correspondence-based physical contact: Knížák or Švecová would trace the outline of his or her hand on a piece of paper and send it to Friedman, who would then trace the outline of his hand over theirs. In this way the friends could touch each other over a distance of thousands of miles and carry on a love game across continents.

Friedman identified strongly with Aktual and Knížák, and he shared Knížák’s ideas about blurring life and art. After looking over some materials produced by the organization, he recognized that his Instant Theatre project, under which he presented public events in California, qualified him as a member.5Letter from Friedman to Knížák. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 708. He wasted no time in founding an American branch of Aktual. In March 1967 Knížák wrote enthusiastically: “Dear Ken, I love you for your activity. We must keep together more places on the globe! To want to live—otherwise. To live otherwise. I’m shaking with your hands for basing of Aktual USA. Right Idea!”6Letter from Knížák to Friedman, postmarked March 14, 1967. Ken Friedman Collection, box 2, folder 6, Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California, San Diego. See Mazzone, “‘Keeping together’ Prague and San Francisco,” 286.

Keeping Together

During the first years of their correspondence, most of their collaborative projects were initiated by Knížák, who emphasized the need for reciprocity between Aktual’s Czech and American branches. He set out to achieve this mutual exchange largely by organizing Keeping Together Manifestations and sent Friedman a mock-up of a publication on KTMs that he hoped might be published in the United States. He even wrote a song in English that was intended as a kind of KTM anthem: “Shake my hand, shake my heart. World is nice, world is love.” The slogan “Keep Together” appeared in English on the cover of the third issue of Aktual magazine in Czechoslovakia, with Friedman’s address printed inside.

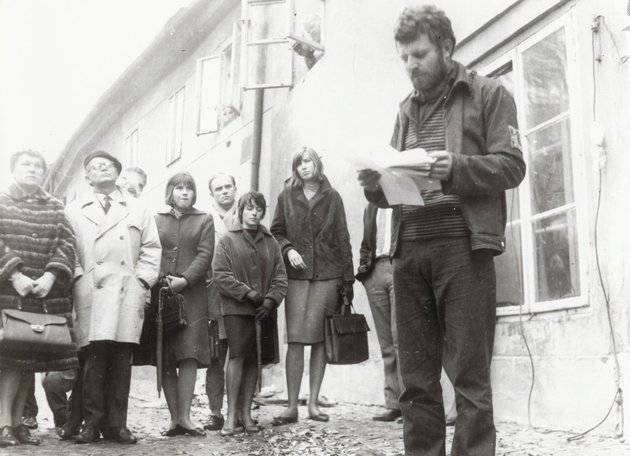

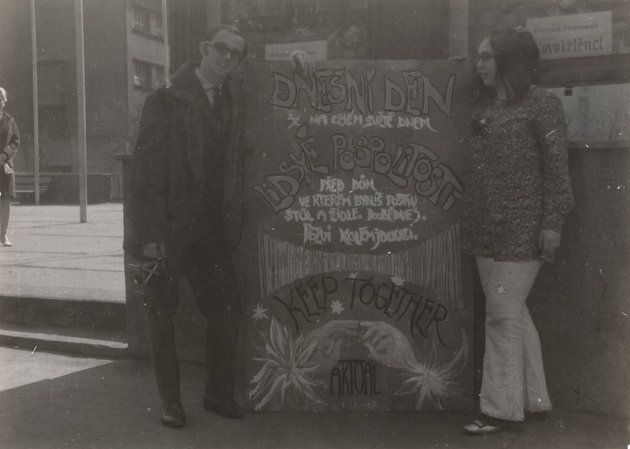

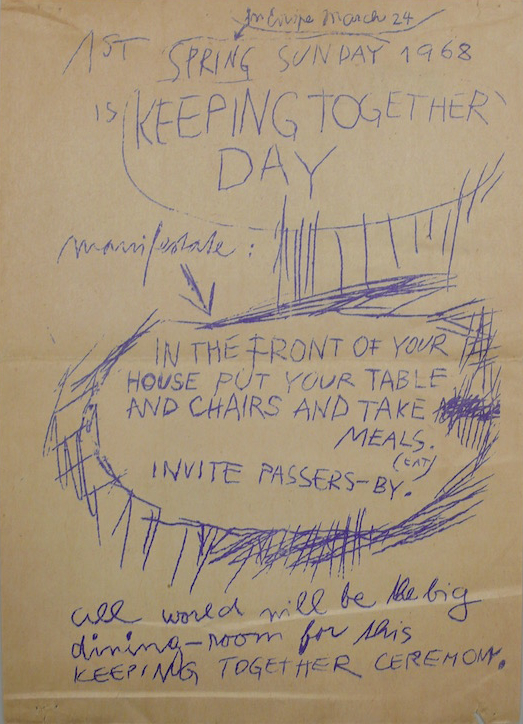

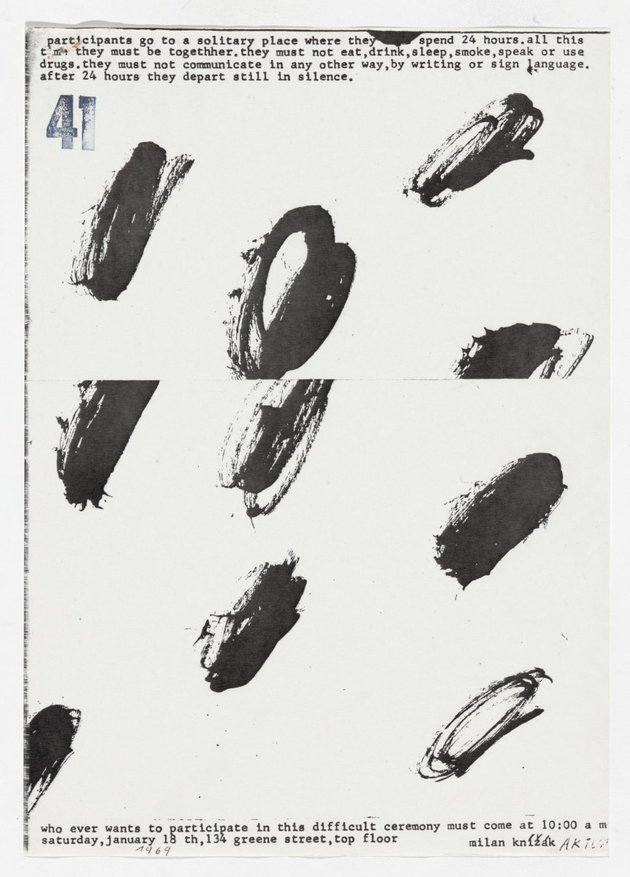

The planning and coordination of KTMs account for a significant portion of the correspondence between Friedman and Knížák. The two associates agreed to inaugurate Keeping Together Day in March 1967 with a full month of KTMs. Every year thereafter, the occasion was to be celebrated on the Sunday following the first day of spring. KTMs could include diverse, unspecified actions and activities; the important thing was for people to be aware that others, perhaps even those on the other side of the planet, were participating in something similar. Knížák conceived of togetherness events that could be organized easily by almost anyone. In the spring of 1967, as a part of the inaugural Keeping Together Day, he proposed a KTM, later titled Difficult Ceremony, in which participants spent twenty-four hours together without eating, drinking, smoking, sleeping, or communicating. The 1968 KTM was less demanding: “Put a table in front of your house and take a lunch. Invite passers-by.”7Letter from Knížák to Friedman. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 714. Knížák asked Friedman to realize this action in the U.S. and to promote its widespread organization by others. To assist, Knížák made a handwritten, unconventional-looking English-language poster, which he mimeographed and sent to California at the reduced rate for printed matter.

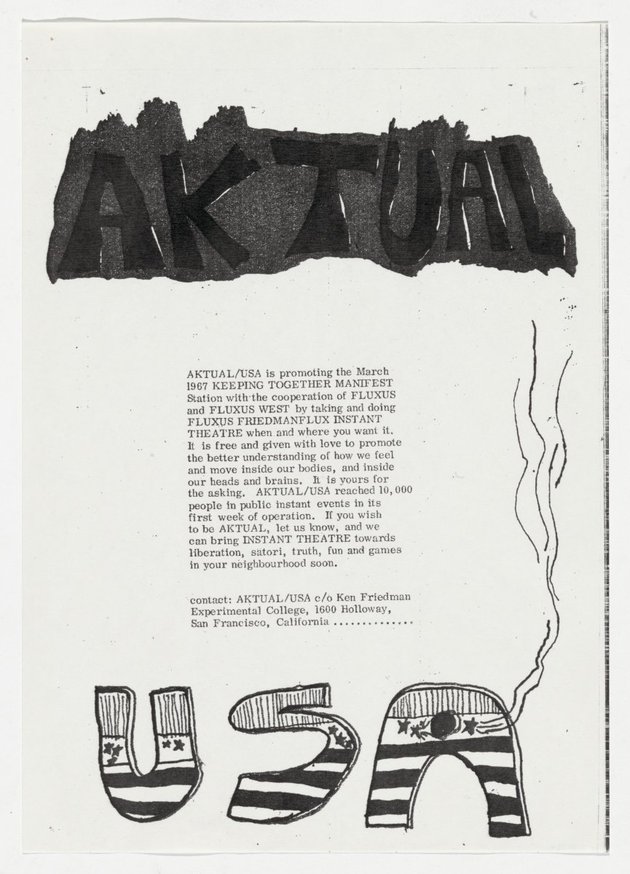

Friedman did not have the resources to implement all of Knížák’s plans, nor did he adhere strictly to Aktual’s program. He ex post facto claimed as KTMs some of his earlier Instant Theater performances that were not directly related to the notion of human togetherness, and on occasion he organized activities with no connection to the ideas coming from Czechoslovakia. As early as March 1967, he printed his own posters promoting Aktual USA. Their messages were in keeping with the ethos of late-sixties California: “Aktual is holding hands, making love, being people, keeping together. Aktual is now—is you.”

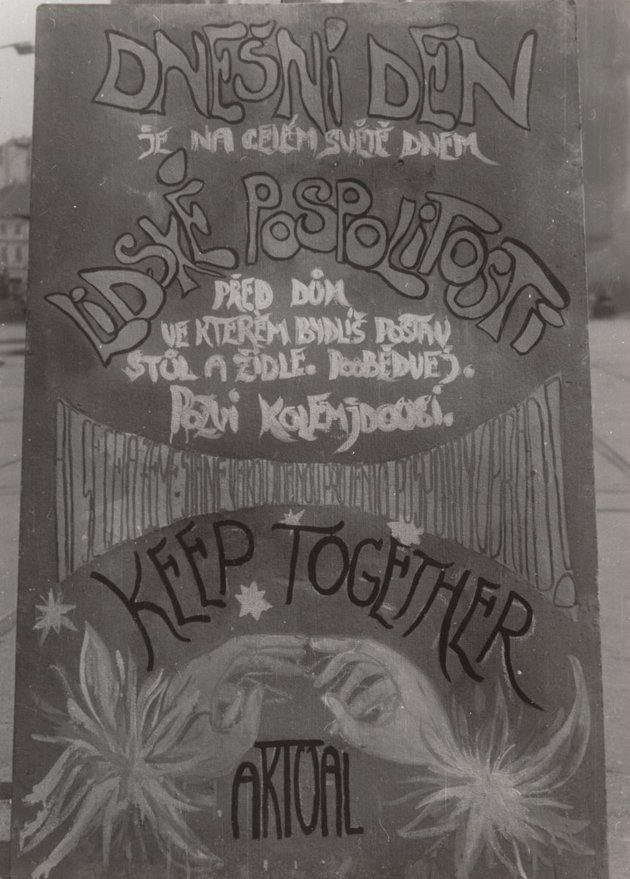

Friedman surely exaggerated when he described the impact of the Aktual movement: “AKTUAL/USA reached 10,000 people in public instant events in its first week of operation. If you wish to be AKTUAL, let us know, and we can bring INSTANT THEATRE towards liberation, satori, truth, fun, and games in your neighborhood soon.”8The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 359. The true reach of Aktual was very likely more modest. In Czechoslovakia, the second annual Keeping Together Day was celebrated on March 24, 1968. Photographs in The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives at The Museum of Modern Art show several Aktual members and sympathizers with handmade posters on Prague’s Národní třída (National Avenue). The posters, designed in the style of American psychedelic art, exhorted people to organize communal lunches and to invite the public to partake. If there was a wider response to this celebration, the documentation has not been found.

Activism

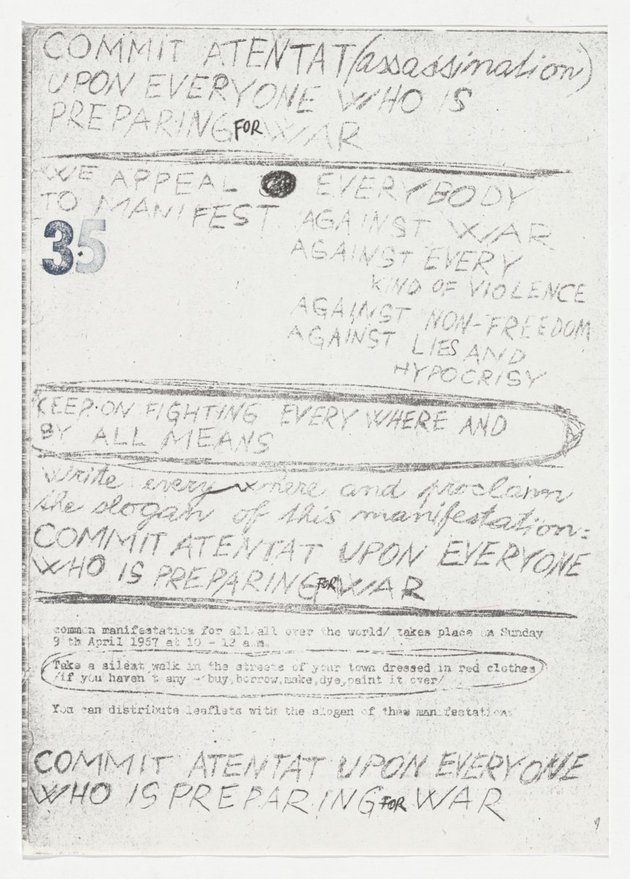

One specific element that Knížák brought to KTM was antiwar activism. As part of the inaugural 1967 Keeping Together Manifestation in Czechoslovakia, Knížák planned or even sent out a letter to foreign embassies in Prague and Czech army officers asking them to disengage from military activities. Written in the name of the worldwide movement for peace, freedom, and nonviolence, the letter was followed by an anonymous mimeographed flyer titled “Assassinate All Those Who Prepare War.” The concept of the flyer came from Robert Wittmann, a member of Aktual, but it was adopted by the whole group. Wittmann and Knížák planned to hold International Atentát Day on Sunday, April 9, 1967. To promote it, Knížák sent Friedman several small accompanying brochures typewritten and copied using carbon paper.

This project, which we will refer to as the Aktual Atentát Project, deserves further clarification. For decades Communist propaganda had thoroughly discredited the concept of fighting for peace. Because of this, few serious art projects east of the Iron Curtain were committed to the cause of world peace,9Among the few was “Indigo Peace Call,” an antinuclear manifesto published by Hungarian artists in 1983. though elsewhere, the pacifism and nonviolence associated with the hippie movement had become fashionable. The shock effect of Wittmann’s militant, absurdist rhetoric calling on people to kill in the name of nonviolence was surely intended to astound its audience. Wittmann and Knížák used the word “atentát” (assassination) even in English translations. In Czech, the word is closely associated with the killing of the German Acting Reich-Protector Reinhard Heydrich by the Czechoslovak resistance in 1942. The crime was avenged immediately by the German occupying forces, who erased an entire village and its inhabitants from the map, not only punishing the assassins, but also murdering anyone who sided with them. The word “atentát” was repeated endlessly in Nazi propaganda. As a result, in Czech, the word acquired a horrific connotation for its association with absolute terror.

Knížák first developed Atentát, as he did Keeping Together Manifestations, prior to his association with Friedman. But the message of Atentát was not clear in English and thus did not gain the support abroad that his calls for togetherness did. The problem is highlighted in a letter from Dick Higgins, dated February 25, 1967: “Dear Milan, We are 100% with you and will keep together with you all. I’ll send you some info about how we keep together here. We’ll get 500 people to keep together in New York and another 500 in San Francisco. Here is some info on how they are doing it there. Your letter ends with the words: Commit ‘atentat’ on each man which is preparing warm! I can’t quite figure out what it means. The word ‘atentát’ doesn’t exist in English, nor does the phrase ‘preparing warm’. Does your sentence mean ‘Kill all those who are preparing war?’ If yes, then I agree. Venceremos!!!”10Letter from Higgins to Knížák, dated February 25, 1967. Published in the samizdat publication koresp fluxu, edited by Petr Rezek in the late 1970s, page 39. Copy preserved at the Academic Research Centre of the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague.

Travel

Knížák is usually identified as one of the Eastern European members of Fluxus, but considering the broad range of his activities, such pigeonholing is misleading. For Knížák, Fluxus was a source of many friendships and validated the path he had chosen in life. Far more important for him, however, were the activities associated with Aktual. Although small, the membership, which was otherwise exclusively Czech, acquired an important international dimension through Ken Friedman. Aktual’s loose organizational structure resembled that of Fluxus, with Knížák as the main organizer and intellectual leader. In his correspondence with Friedman, he is sometimes jokingly referred to as the “bishop” of the religion of Aktual. Without him, Aktual would not have existed.

Maciunas invited Knížák to Fluxus headquarters in New York in 1966. Two and a half years later, Knížák obtained permission to leave Czechoslovakia and, in the summer of 1968, traveled to New York. He worked briefly for Maciunas’s Fluxhouse cooperative and later supported himself as a construction worker.

Knížák and Friedman first met face-to-face in the spring of 1969 in California, where Knížák had been invited by Friedman to give a lecture. “Ken Friedman was waiting for me. He looks like a younger version of the Czech artist Franta Sedlák. But K. F. is a conceptual artist and is 19, although he doesn’t like to say so about himself, and his parents have a beautiful house in San Diego with a terrace and a pool where I even went for a swim.”11Milan Knížák, Cestopisy (Prague: Post, 1990), 16. Knížák’s time in California was not one of concentrated artistic activity; it was more of a holiday, an enactment of the motto “live otherwise,” filled with long discussions about the future.

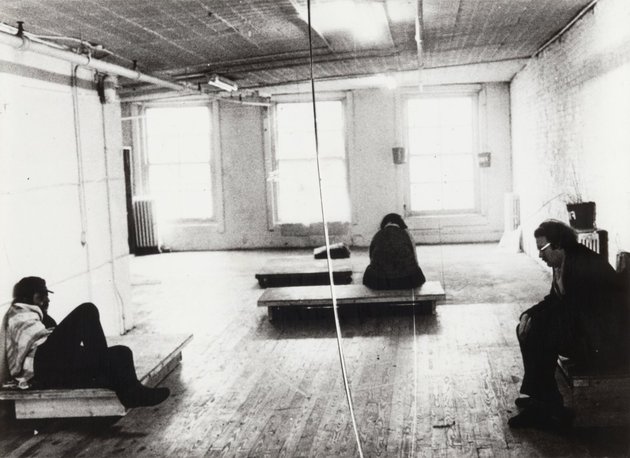

It is clear from his travel journals that Knížák had little interest in the artistic goings-on in New York.12Knížák’s letters from New York were originally published as “Dopisy z New Yorku,” in Sešity pro mladou literaturu 4, no. 33 (September 1969): 17¬–21. For selections in English translation, see Claire Bishop and Marta Dziewanska (eds.), 1968–1989: Political Upheaval and Artistic Change (Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 210–219. He was repelled by the degree of institutionalization he found in the world of art, which he saw as too detached from life. His own work received scant attention. In New York, only a half dozen people turned up in response to the hundreds of invitations issued to his Difficult Ceremony, and some participants escaped through a window only a few hours after the start of the twenty-four-hour event. Difficult Ceremony of 1969 was one of the few works Knížák realized during his stay in the United States.

Knížák did not use his time in the United States to build new and lasting relationships within the art community. He considered important the people with whom he had been corresponding before coming to the U.S., and he continued to value them. Knížák’s need for a universal coming-together declined during his two-year American sojourn, leading to a reduction in Aktual’s activities rather than to the movement’s flowering. Paradoxically, the modest, more or less virtual, and internationally ambitious Aktual movement did better when its principals lived in separate countries.

When his Czech exit visa expired in April 1970, Knížák decided to return home. His correspondence with Friedman continued after his return, with Friedman wanting to pursue their joint plans and experiences: “We believe in the same truth, love the same love, work for the same goal.”13Letter from Friedman to Knížák. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 358. Knížák sent him the kinds of requests that are common among good friends: he was looking for a book on the history of communes and frequently reminded Friedman to send him the records he received free from a music-critic friend. The desire to coordinate joint projects weakened, however. In 1970 Czechoslovakia was a different place from what it had been in 1968: the repression associated with the hard-line Communist regime’s consolidation of power was in full swing, and Knížák was facing even greater obstacles to staging public activities than before. On top of that he suffered serious financial problems. Aktual was reduced to just a few of his closest friends and effectively ceased to exist.

At home, Knížák was effectively isolated from the public and had no urge to engage himself with the local art community. After 1970, almost all of his exhibitions, collectors, and supporters were outside of Czechoslovakia. He left Prague for the countryside, but, under police surveillance, organized no further Keeping Together Days. Friedman kept those celebrations going in California, however, and for the 1972 event was joined by artists from elsewhere in the United States and in Canada. Friedman tried to assist Knížák, who was arrested for several months in 1972-73 and received a two-year sentence in 1973 after artworks by him were seized at the Czech border and judged pornographic and harmful to the country’s image.14For a description of the case, see David Mayor, “Action on Behalf of Milan Knižák” (Collumpton [Devon]: Beau Geste Press, 1973).

Raising Global Consciousness

In their time, Keeping Together Manifestations represented a utopian attempt to create a global network of togetherness, but it took another letter-driven project—this one aimed at saving Knížák from judicial prosecution—to elicit a strong response by and the active involvement of the international community. The petition calling for Knížák’s release was distributed by various groups associated with Fluxus and was signed by prominent individuals including Allan Kaprow and Harald Szeemann. Knížák, who was aware of the power of international public opinion, had helped to initiate the campaign. In a letter to the German collector Wolfgang Feelisch, dated February 19, 1973, he wrote: “Please ask the people around the world, all the people you know, to write letters and protest to Czech government against it, to publish protests and notes and news about it in all newspapers and magazines around the world. . . . Please do all you can because I . . . can do very little myself, please tell what happen to everyone in the world because if I will go to the jail, all Czech art will go with me, all art freedom will be jailed, too.”15Milan Knížák, unpaginated brochure in The MoMA Archives A.B. K 6203 A12m 84.0801. Knížák’s sentence was commuted to probation: he was not allowed to publish in Czechoslovakia, to work in public spaces, or to organize even private group activities.

Bridging great distances and an even greater geopolitical divide, the correspondence between Knížák and Friedman in the late 1960s and early 1970s linked two individuals with similar ideas, engaging them in a kind of long-distance love affair. Knížák remembers how important it was to receive confirmation that he was not alone in his way of thinking. And he himself was able, through his letters, to influence a kindred spirit in far-off California. For Knížák, as for other Eastern European artists, the international art world, accessible via the postal service, became one of the few—if not the sole—public platform for his work. Knížák would have to wait until 1979 to set foot in that world once more; only then did the Czech authorities again allow him to travel abroad.

Milan Knížák never attempted to reestablish Aktual and instead pursued an individual art career. After 1989 he became Dean of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague and from 1999 headed the National Gallery in Prague for almost twelve years. His current political views come close to right-wing libertarianism. Ken Friedman continued with his artistic endeavors and became the leading historian of Fluxus. He held several teaching and research positions in the fields of philosophy of science and philosophy of design. Since 2007 he has served as Dean of the Faculty of Design at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia.

- 1Dick Higgins, “Fluxus: Theory and Reception,” in The Fluxus Reader, ed. Ken Friedman (Chichester: Academy Editions, 1998), 224, and Ken Friedman, “Fluxus and Company,” in The Fluxus Reader, 244.

- 2Friedman emphasized this idea in later years as well. For example, a Keeping Together Manifestation organized by Friedman in 1971 was described in a university newspaper as a disorganized bacchanalia of building, giving, and receiving. The article quotes Friedman as saying that KTMs are a tool for changing social behavior. Geoffrey Anderson, “Aktual Art Is Just Part of the KTM,” San Diego Daily Aztec (April 16, 1971).

- 3Letters are not dated, the earliest surviving date mentioned in them is March 1, 1967. The year 1967 is given also in Marian Mazzone, “‘Keeping together’ Prague and San Francisco: Networking in 1960s Art,” in Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research 7, no. 3 (2009): 285.

- 4Letter from Švecová to Friedman. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 709.

- 5Letter from Friedman to Knížák. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 708.

- 6Letter from Knížák to Friedman, postmarked March 14, 1967. Ken Friedman Collection, box 2, folder 6, Mandeville Special Collections Library, University of California, San Diego. See Mazzone, “‘Keeping together’ Prague and San Francisco,” 286.

- 7Letter from Knížák to Friedman. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 714.

- 8The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 359.

- 9Among the few was “Indigo Peace Call,” an antinuclear manifesto published by Hungarian artists in 1983.

- 10Letter from Higgins to Knížák, dated February 25, 1967. Published in the samizdat publication koresp fluxu, edited by Petr Rezek in the late 1970s, page 39. Copy preserved at the Academic Research Centre of the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague.

- 11Milan Knížák, Cestopisy (Prague: Post, 1990), 16.

- 12Knížák’s letters from New York were originally published as “Dopisy z New Yorku,” in Sešity pro mladou literaturu 4, no. 33 (September 1969): 17¬–21. For selections in English translation, see Claire Bishop and Marta Dziewanska (eds.), 1968–1989: Political Upheaval and Artistic Change (Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 210–219.

- 13Letter from Friedman to Knížák. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives, series I, folder 358.

- 14For a description of the case, see David Mayor, “Action on Behalf of Milan Knižák” (Collumpton [Devon]: Beau Geste Press, 1973).

- 15Milan Knížák, unpaginated brochure in The MoMA Archives A.B. K 6203 A12m 84.0801.