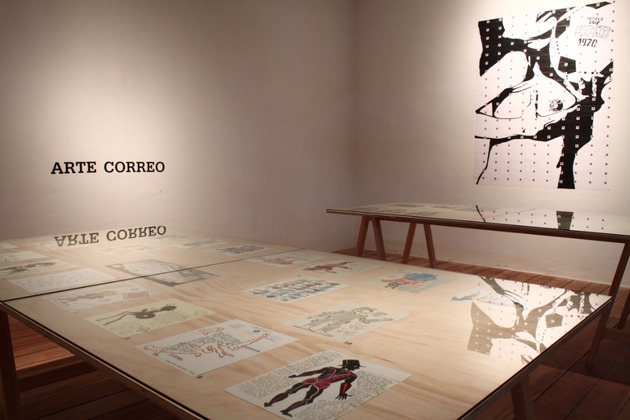

Curator Mauricio Marcin sketches a brief history of mail art, as told through a variety of archives in Mexico City, arguing that these remnants demand that we “keep on thinking.” This essay is an adapted and translated version of the article “Arte Correo en un Libro,” originally published in Mauricio Marcin (ed.), Artecorreo (Mexico City: Museo de la Ciudad de México / Editorial RM, 2011). The publication was produced as part of the exhibition project Arte Correo, held at the Museo de la Ciudad in Mexico City from 27 October 2009 to 27 February 2010.

Preamble

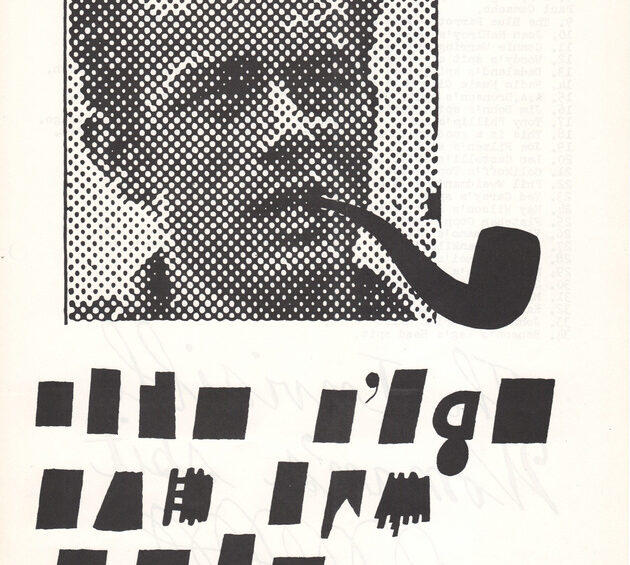

An anonymous mail artist once said that mail art arose from the coming together of the words mail and art. The term designated a postal dispatch as a vessel for art, or rather, as art—a twist to the proposition of a famous Frenchman who converted a urinal into imaginary gold.

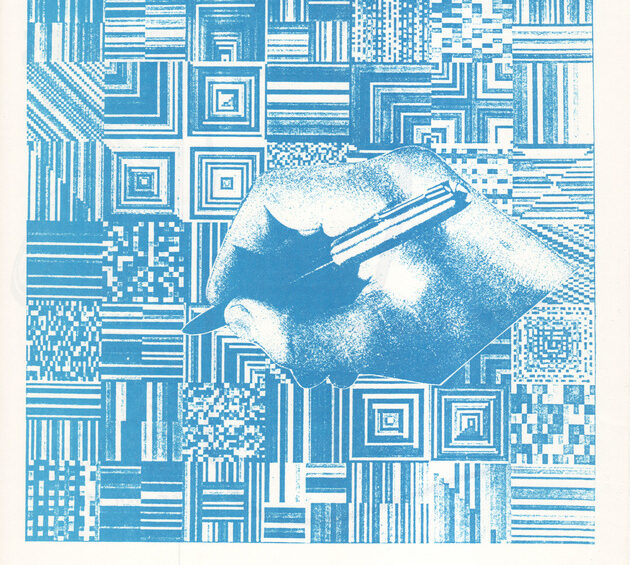

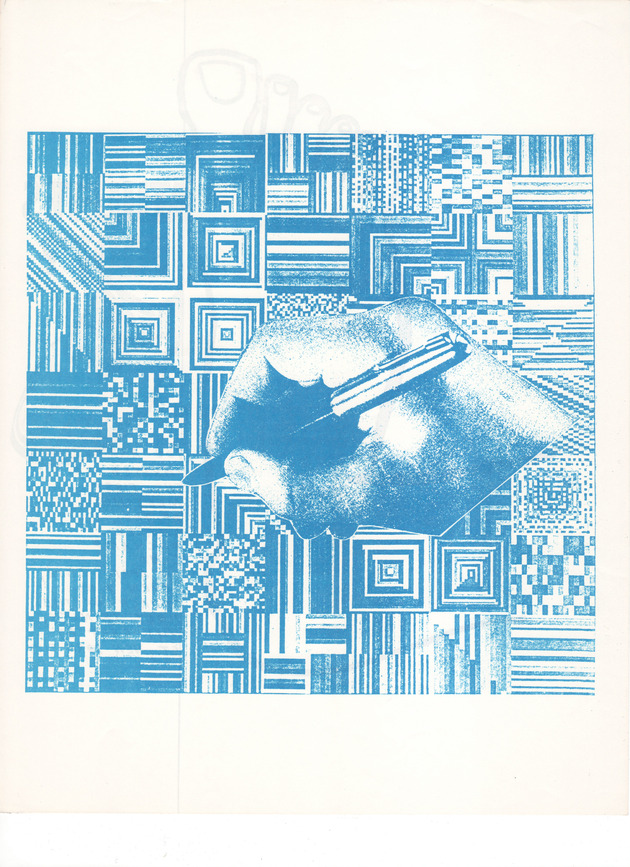

Certainly, mail art exists by its very enunciation, but it is also inseparable from an action that is neither conceptual nor imaginary, but instead physical and real: the mailing. Mail art is not only a new logos; it is also matter in motion, transit, and reciprocity.

All works of mail art have one thing in common: they were sent from one place to another.

I myself hold that two rivers flow through mail art: memory and oblivion. These two rivers run through each work.

Some Facts (Papers in Flight)

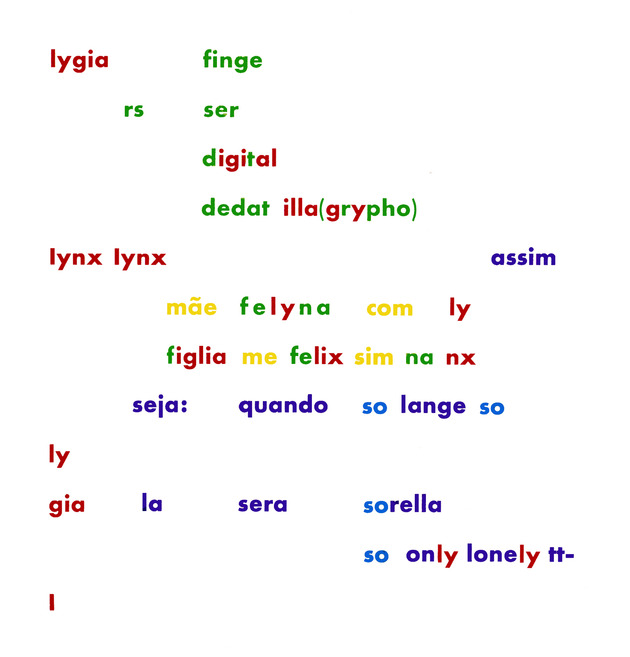

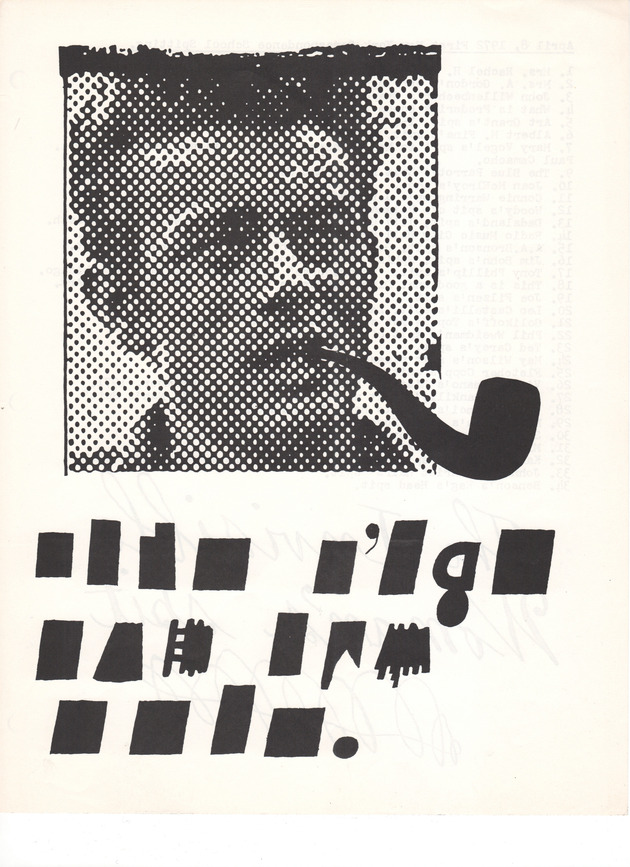

In March of 1966, the Aristos University Gallery at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) inaugurated the exhibition Poesía Concreta Internacional (International Concrete Poetry). The exhibition catalogue reproduces the following remarks by Professor Max Bense, which first appeared in the preface to the anthology International Concrete Poetry, published in Stuttgart in 1965: “Concrete poetry has nothing to do with the word’s grammatical or syntactical linear relations, either from a semantic or an aesthetic point of view.” By contrast, he affirms: “Concrete poetry is based on the visual relations among its various elements and their deployment in flat, two-dimensional space.”

This concept of space that Bense refers to in the context of concrete poetry would also show up in mail art, where it can be considered an influence and an antecedent.

At the same time, we might remember that concrete poets (especially those of the Brazilian group Noigandres) reread Mallarmé’s poem Un coup de dés (A throw of the dice) published toward the end of the nineteenth century. The verses showed them another way to visualize, read, and occupy space on the page.

As Borges said of Edgar Allan Poe, “The detective novel has created a special type of reader. This tends to be forgotten when we judge Poe’s work; because if Poe created the detective story, he consequently created the reader of detective fictions.”

Concrete poets also created a new type of reader and a new way of reading and looking at images.

The ancient form of epistolary writing is limited to the law of progression, that is, to that of time. An epistle encodes its meaning in the succession of words on the page; meaning arises from the sequence of words. An epistle, to state it plainly, is written and read from left to right, and from top to bottom, over time. The same is true of a literary text.1Ulises Carrión’s “El Nuevo Arte de Hacer Libros” (The New Art of Making Books) was published in Plural (n. 41) in 1975 and appeared in English in Kontexts 6 and 7 that same year. The essay is available online in Spanish and in English. Martha Hellion has studied and gathered the artist’s work and coordinated Ulises Carrión: ¿Mundos personales o estrategias culturales? (Ulises Carrión: Personal Worlds or Cultural Strategies? (Mexico City: Turner, 2002). Mail art, by contrast, has no center, and it has neither left nor right. Its meaning boils down to the relations produced by the various signs contained in the whole space; these are neither linear nor successive relations as in epistolary and literary texts, but are rather multidirectional and simultaneous. Mail art proposes the impossible: a vision of infinite time.

Another particularity of the Concrete Poetry exhibition influenced the practice of mail art in Mexico. To explain it, we need to mention Mathias Goeritz, guest curator of the exhibition. During the late 1960s, Goeritz had a network of correspondents in Europe and America (which precedes his arrival in Mexico), with whom he exchanged letters, photographs, graphic objects, collages, documentation of works, postcards, magazine cuttings, photocopies, seals, stamps, etc.—all by mail. Suffice it to imagine the possibilities of an envelope and a jar.2There’s a saying in Mexico that goes “everything fits in a jar if you organize it well.” Goeritz’s correspondence was sent back and forth, dispersed throughout Europe and America.

During the years preceding the exhibition, Goeritz was already receiving materials by mail that must have shaped it. This is how he first established contact with the Brazilian concrete poets Augusto de Campos, Haroldo de Campos, and Décio Pignatari, the Swiss poet Eugen Gomringer, the German typographer Hansjörg Mayer, the Swiss artist Dieter Roth, and many other artists who were involved in the mail art movement. This model for exchanging art opened a new way for Mexican mail artists.

Goeritz did not consider himself a mail artist even when he established communication with so many people who took an active role in the creation of the network, such as Clemente Padín and Edgardo Antonio Vigo.3In 1967, the artists Clemente Padín, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Guillermo Deisler, and Dámaso Ogaz, who were based in Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and Venezuela, respectively, were also the editors of publications focusing on Latin American experimental poetry and mail art. In 1967, they began an exchange, by mail, of their individual journals: Los Huevos del Plata (Padín), Diagonal Cero (Vigo), Ediciones Mimbre (Deisler), and La Pata de Palo (Ogaz).

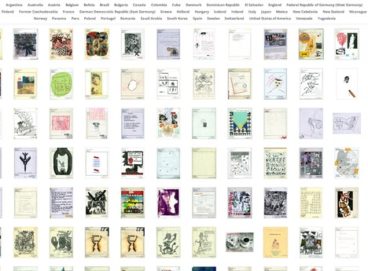

In 1974, under the Uruguayan military dictatorship, Padín organized the Festival de la Postal Creatíva (Creative Postcard Festival) at the Gallery U in Montevideo. In 1975, the Brazilians Paulo Bruscky and Ypiranga Filho held, in Recife, the Primeira Exposicão Internacional de Arte Postal (The First International Exhibition of Mail Art). That same year, Vigo and Horacio Zabala organized, not without humor, the Última Exposición Internacional de Arte Postal (The Last International Exhibition of Mail Art) in the Gallery Arte Nuevo in Buenos Aires. It does not matter which exhibition came first and which followed, because together they show that, within a decade, many artists from distant parts of the world were exchanging art by mail. The mailings are evidence of these exchanges, which in turn reveal the existence of the network.

The Last International Exhibition of Mail Art gathered works by 199 artists from 25 countries. Among them, the only submission from Mexico was from Pedro Friedeberg, who met the show’s organizer, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, through Mathias Goeritz. When Goeritz moved to Mexico City – after a brief stay in Guadalajara – he taught architecture at the Universidad Iberoamericana, where, in 1955, he met Friedeberg in his classes. From that moment on and for many years to come, they exchanged a copious amount of correspondence. Sometimes their letters brought news of personal or familial matters, together with opinions on sculptural or architectural projects. At other times their exchanges contained artworks. In 1988, Goeritz wrote to Freideberg’s daughter Diana: “Today I am sending you a paper sculpture and a drawing.”

In a letter from 1982, Friedeberg sent Goeritz diagrams for three yoga poses (Sarvangasana, Halasana, Mayurasana), suggesting that he practice them before going to bed: “They will help you get thru life plus facilement.”

Friedeberg’s letters were beautifully decorated with drawings and seals. His pleasure in painting and sending letters remained constant over fifty years. I calculate—and this is a very subjective estimate—that he has sent approximately two thousand in the last days, from a big palace with labyrinths and gardens.

Dispersed Memory

I’m not aware of the way in which many artists started corresponding with each other. In any case, Friedeberg somehow knew Ray Johnson, who was described by Grace Glueck in the New York Times as the most famous unknown artist in New York.4Grace Glueck, “What Happened? Nothing,” New York Times, April 11, 1965.

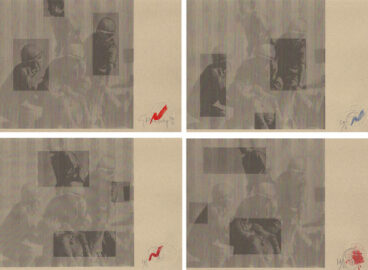

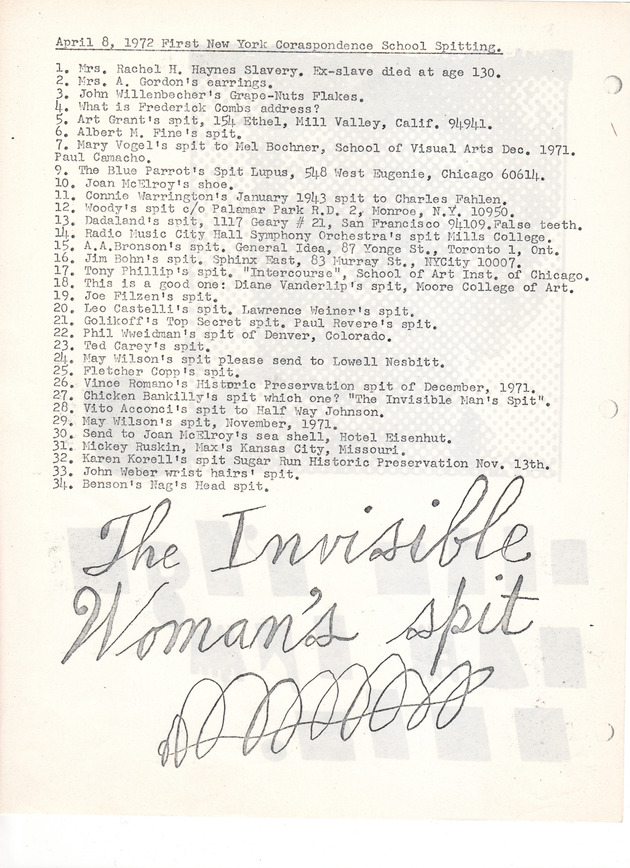

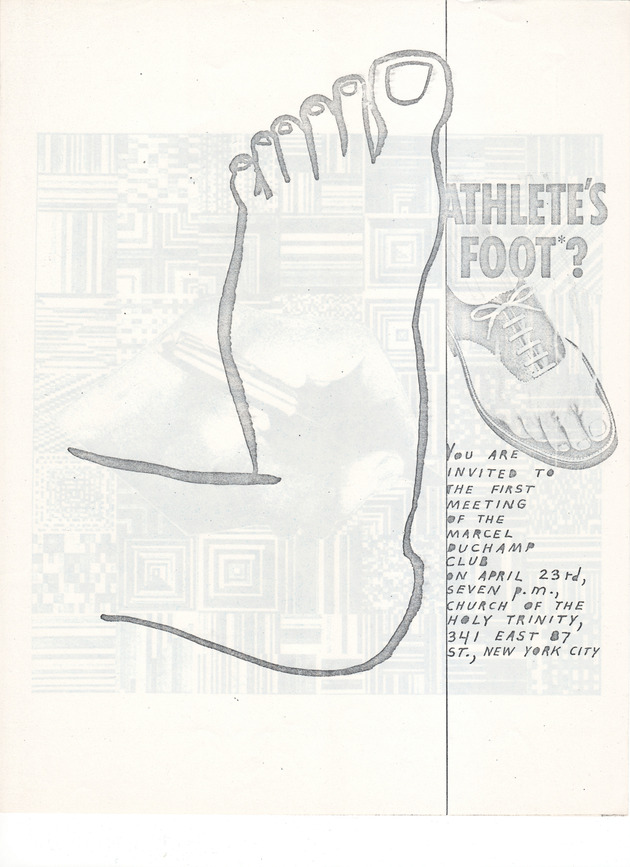

In 1962, Johnson initiated a series of mailings instructing the recipient to add something to the work received and send it on to someone else, who would follow the same instructions. That same year, he founded the New York Correspondence School, a fictional entity that served as a conceptual base for his mailings over the next three decades.5Ed Plunkett gave the New York Correspondance School its name in 1962. In a play on words, Johnson employed the terms “Correspondence” and “Correspondance “ interchangeably. Plunkett commented: “It never claimed to be an innovation. In any case, it meant something, to go back to a tradition going back to primordial times. Examples in which communication was an art form can be cited throughout history. Cleopatra had herself rolled into a carpet to be presented to Julius Cesar.” Art Journal, Spring 1977.

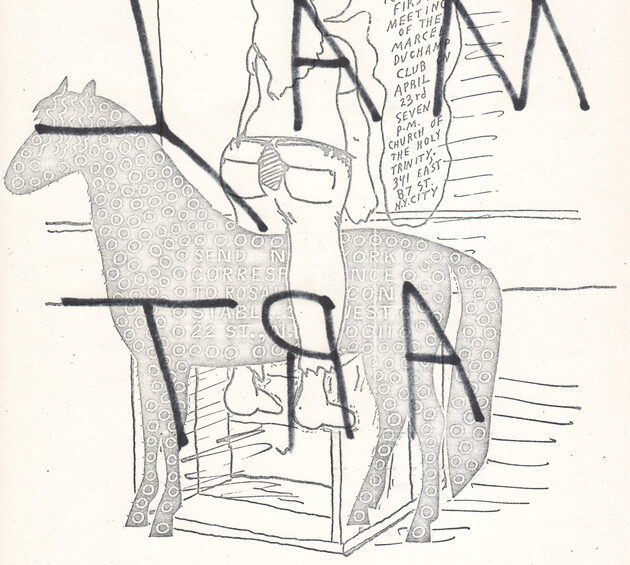

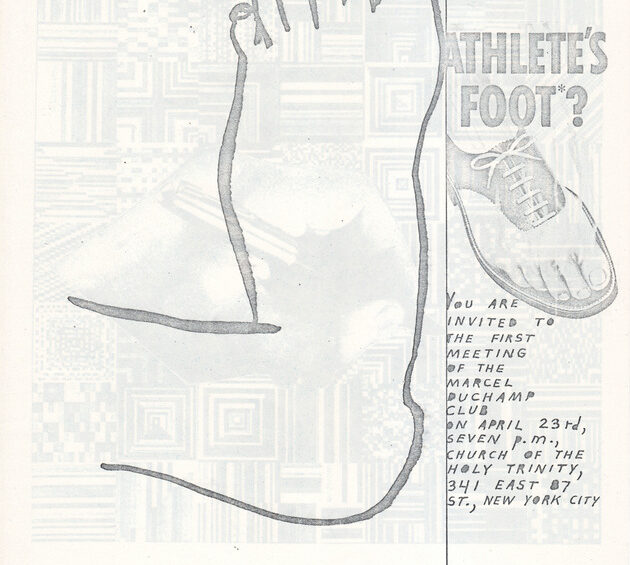

The first meeting of the New York Correspondence School took place on April 1, 1968. To all appearances, nothing happened. Since 1961, Johnson had held events titled Nothings in a stance of opposition to Happenings. He organized various meetings (such as the Seating-Meeting) about which he wrote reports and chronicles that he then photocopied and distributed by mail to those attending as well as to unknown recipients (making it possible for an unexpected audience to receive his work and participate in future events). This non-exclusive, random form of distribution became a recurrent model for mail art.

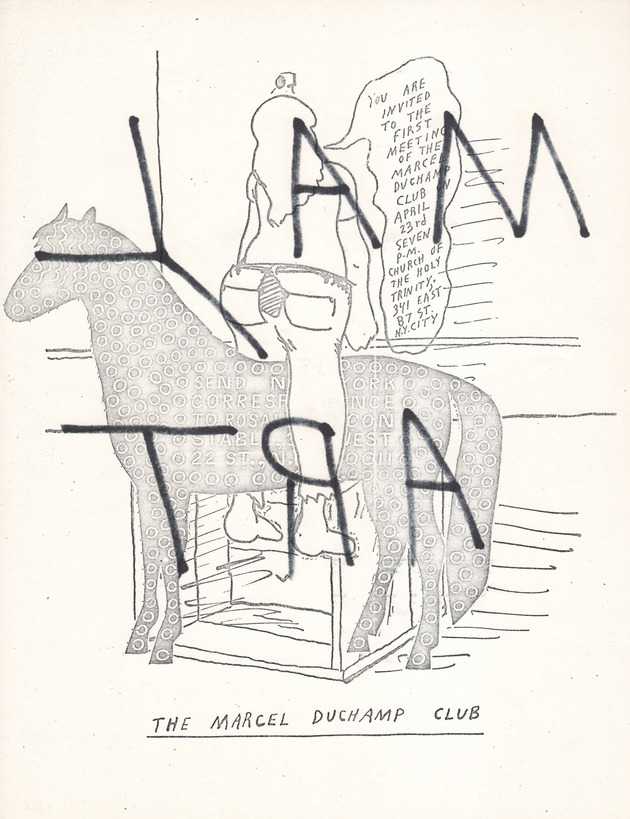

In 1972, Johnson invited Friedeberg to participate in the First New York Correspondence School Spitting, to which Friedeberg contributed by spitting on the avenue known as Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City. Johnson also invited him to the First Meeting of the Marcel Duchamp Club, but Friedeberg did not attend. They corresponded for years; these exchanges enabled Friedeberg to participate in the activities of Johnson’s fictional school and in those of the Fluxus group, with which Johnson was affiliated.

Neither Gift nor Barter: Cheers!

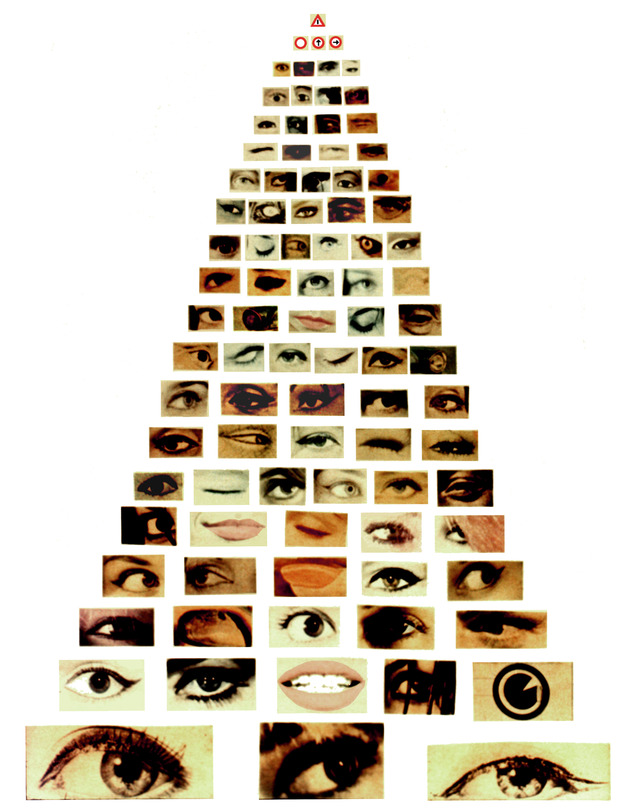

After the repression of the student movement in Tlatelolco, Felipe Ehrenberg and Martha Hellion leave Mexico, pass through New York, and arrive with their two children in London in 1970.6Hundreds of people are thought to have died in the massacre, which took place ten days before the opening of the summer Olympics in Mexico City. That same year Ehrenberg sends two hundred postcards from England to Mexico. They are addressed to Alberto Híjar and are painted irregularly with black stains.

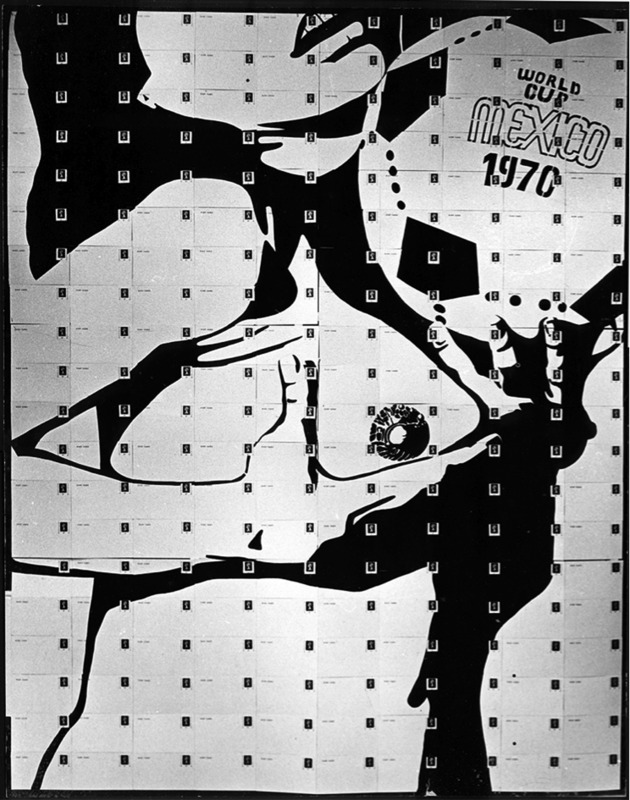

Híjar and those attending the third Salon Independiente (Independent Salon) at the UNAM’s Museo Universitário de Ciencias y Artes (University Museum of Arts and Sciences) mounted the two hundred postcards on a wall, following instructions to paint by number. The mural-size image that resulted showed a woman with slightly parted lips, her neck arched in ecstasy. In her left hand she held a football, alluding to the World Cup that took place that year in Mexico. With her right hand she squeezed her breast, offering invisible milk.

The work’s title, Arriba y Adelante (Upwards and Onwards), alludes to the campaign slogan of Luis Echeverría, who would become president of Mexico that same year.7The full title of the work is: Obra secretamente titulado Arriba y Adelante . . . y si no pues también (Work secretly titled Upwards and Onwards . . . whether you like it or not). The collaboration of the public in assembling the painting/postcard installation also recalls another slogan, “Together we are the solution,” used by José López Portillo six years later for his presidential campaign and which, much later, would be parodied as “together we are the corruption.”

Many of Ehrenberg’s works at the time were multiple reproductions that he sent by mail. In this manner, he lived simultaneously both in exile and proximity. In 1971, Ehrenberg and Hellion moved from London to Devon to establish the Beau Geste Press with David Mayor and Chris Welch. The name of the publishing house came from the contraction of beautiful and Gestetner, alluding to the handsome German mimeograph machine they used to print the works of visual poets, conceptualists, and Fluxus artists. The press, housed in a twelfth-century cottage, allowed Ehrenberg to collaborate with numerous artists based in Europe. Upon his return to Mexico, his address book would supply the means for redoubling contacts among Mexican- and European-based artists. One can imagine the consequences.

No Desire for Genealogy

Among the early practitioners of mail art in Mexico, we find Aarón Flores, who in 1979 presented Expocorreográfica (Expomailgraphics), a show of postcards that he duplicated with a photocopier to send to friends, museums, galleries, and magazines. Some documents attribute to Flores the creation of the CRAAG (Centro Receptor de Arte y Archivo General [Central Repository of Art and General Archive]), which consisted of a cardboard box for storing received mailings.

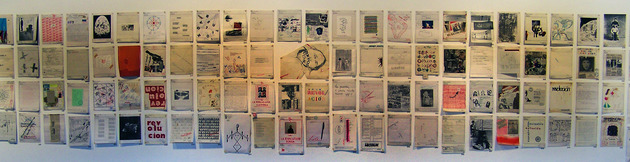

Also in 1979, the exhibition Arte-Correo México (Mail-Art Mexico) took place in the Museo Carrillo Gil. Organized by the Mexican artist Sebastián, the show presented approximately two hundred mailings from Mexico, Brazil, Italy, Holland, the U.S, France, England, Canada, Switzerland, Germany, Bulgaria, Austria, Japan, Cuba, China, Argentina, Colombia, and Poland.

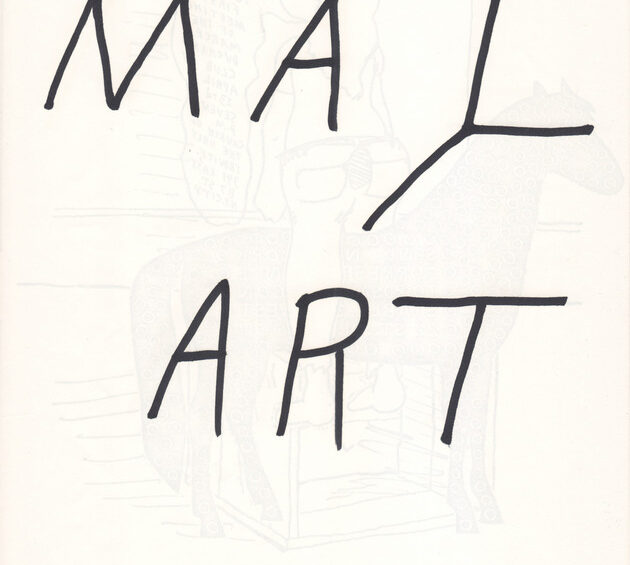

Some Mexican artists were very active in the network, among them Mauricio Guerrero, Manuel Marín, Magali Lara, Felipe Ehrenberg, Helen Escobedo, José Luis Cuevas, Mathias Goeritz, Grupo Março, Pedro Friedeberg, Aarón Flores, Sebastián, César Espinoza, Araceli Zúñiga, Blanca Noval, Marcos Kurtycz, Maris Bustamante, Mónica Mayer, and Alberto Gutiérrez Chong.

I don’t consider this a pointless listing of names. Each of the artists mentioned constitutes a link to other mail artists, and these to others who have not been mentioned.

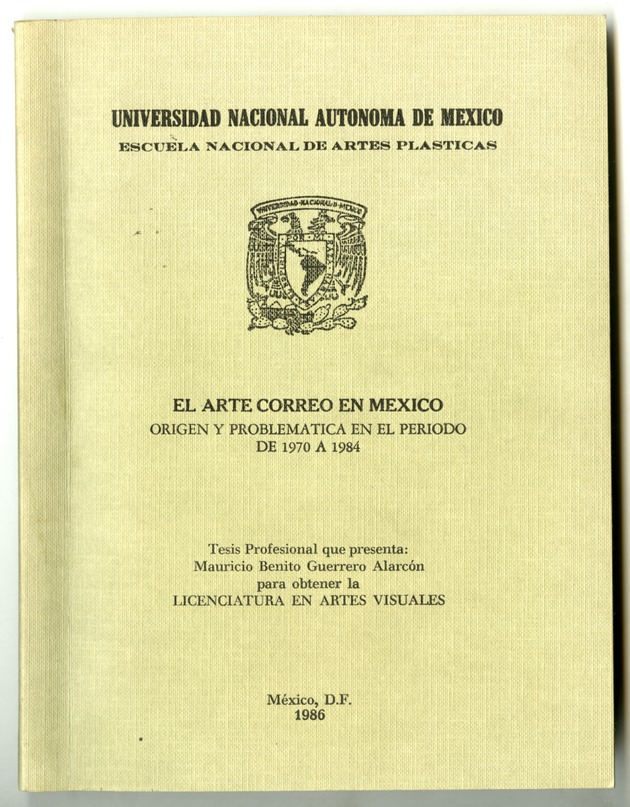

A thesis on mail art presented by Mauricio Guerrero at UNAM in 1986 gives a penetrating account of the movement in Mexico between 1970 and 1984. In it there are lists of participants in the network, interviews, directories, dates, and chronologies. It also includes statements by the artists discussing mail art. Some refer to the movement as Postal Art, Art by Mail, Art as Correspondence, Eternal Network, or the Big Monster. Each artist has a particular conception of the movement.

Guerrero writes: “In general it is agreed that thanks to chance [mail art] has yet to be defined; the moment this happens, it will become trapped and cornered, ceasing to be what it still is today: an alternative.”8In interviews, the artists have given contradictory dates. These discrepancies are reflected in published sources that we have consulted: an exhibition took place in 1974 and in 1979. We searched for writing in stone, as it were, to corroborate them; a paper, an invitation. But history is written as much as it is erased. Mail artists also wrote in sand.

In 1990, the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (Autonomous Metropolitan University) reprinted Guerrero’s work with a foreword by Juan Acha. The theorist celebrates the book as being at the forefront “because it dwells on non-objectualism. As we know, mail artists do not consider the meaning of their works to reside in their materiality as objects. They locate meaning in the effect of the works on its recipients. The lack of a conventionally neat and lasting work, in fact, contravenes the present overvaluation of the object propagated by our consumerist societies. Today, the work of art in its status as object has become an end in itself, whereas in antiquity it was always a means of enriching our daily aesthetic relationship with nature and our fellow beings.”9Guerrero, Mauricio, “El Arte Correo en México” (Masters Thesis, UNAM, 1990). Many of the artists discussed by Guerrero—as partially listed above—can be researched elsewhere; much information on mail art and the artists involved can be found on the Internet.

Mail artists attempted to de-objectify creative work in order to extract it from the cycles of consumption and alienation. They also emphasized the prohibition to commercialize mailings. The works were sent on the condition that they not be sold.

Today, the art market has managed to court certain artists who violated this principle. Many others still abide by it and do not to profit from their mailings; they continue to disseminate them and make them public.

A statement by Bourriaud comes to mind: “That which cannot be commercialized is destined to disappear.” I also recall Camille de Toledo: “Everything that the State and the market haven’t diminished, they will nevertheless end up destroying.” Finally, I recall lines from Borges’s “For a Version of the I Ching”:

But don’t lose heart. The slave’s dungeon is black, / The way of things is iron, cold and hard, / But in some corner of your prison yard / There may be an old carelessness, a crack. / The path is like an arrow, deadly straight, / But in the cracks is God, who lies in wait.10Borges, Jorge Luis, “For a Version of the I Ching,” Translated by Robert Mezey, The New York Review of Books, June 11, 1992.

Deaths and Impermanence

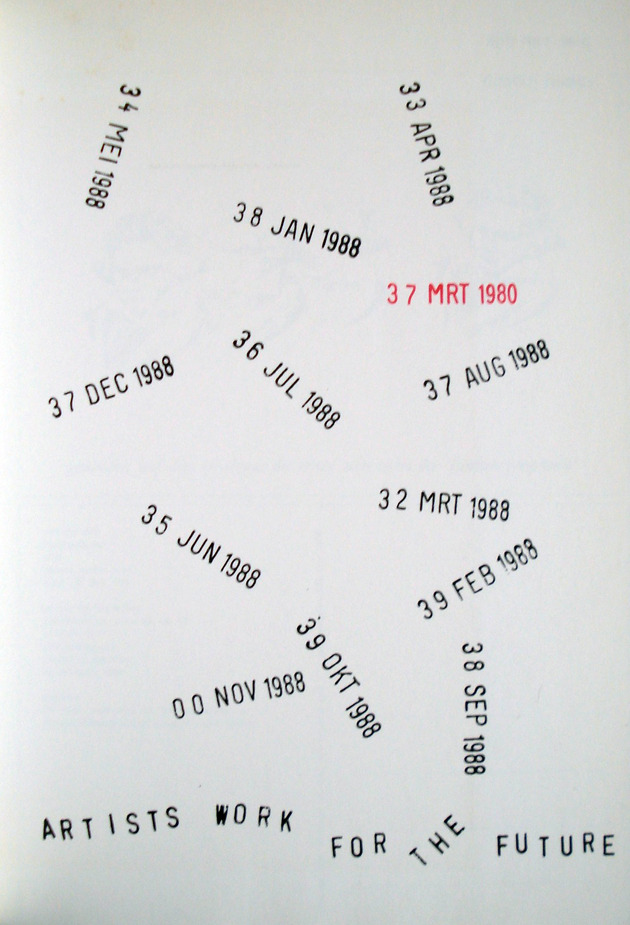

The 1980s was the most eventful decade in the development of the mail art movement in Mexico; it was a moment of intense exchange and flux. Yet toward the end of the decade mail art fell into disuse, becoming extinct. Some have suggested the growth of the network and its saturation as probable causes.

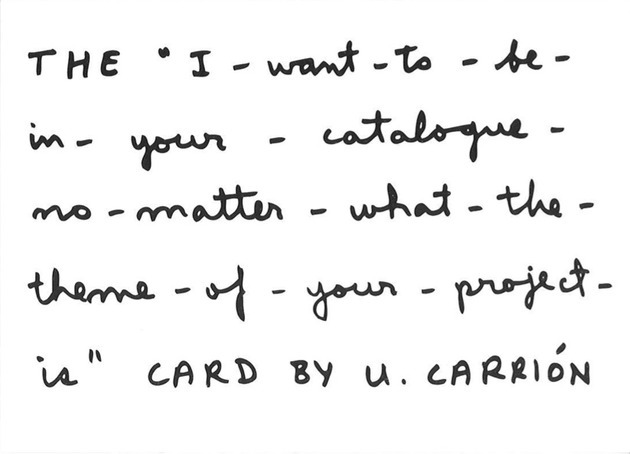

According to César Espinosa and Araceli Zúñiga, initiators of the Poema Colectivo: “It’s true that [mail art] broadened the horizons of those producing it in the artistic circuit, but at the same time it engendered a whole range of formalisms and epigonisms that eventually made it short circuit, given the zeal to respond indiscriminately to all kinds of invitations and thematics.”11César Espinoza and Araceli Zúñiga, La Perra Brava (Mexico City: UNAM, 2002).

A work by Ulises Carrión prefigures the end with some humor. On a blank postcard he wrote in lower case letters: “I don’t care what your project is about, I just want to be in it.”

Some artists moved on to new practices and media that allowed them to continue the artistic decentralization to which mail art aspired.

“When from each village and province creative messages can be sent and be known by or transmitted to a multiplicity of places in opposition to the dominant art centers established since the Second World War, where a plot of galleries, museums, critics, and dealers control a closed circuit of marketing and prestige that dominates art worldwide, then they are no longer marginalized in their expression. It would be fitting to use the possibilities of this system and orient oneself toward the proliferation of these localized circuits of communication—controlled by the same emitters and receptors—with the effect of interweaving and flowing through all social strata on different terms and counter to the intrinsically repressive normative codes of the dominant culture and communication [systems].12Ibid.

Addicted to Ruins

Researching mail art, we may want to compile everything, to track every mailing and each response, an impulse similar to those of cartographers in a memorable poem by Suárez Miranda (based on one by Lewis Carroll).

“In that Empire, the Art of Cartography achieved such Perfection that the Map of a single Province took up an entire City, and the Map of the Empire, an entire Province. With time, those Outsized Maps didn’t satisfy and the School of Cartographers raised a Map of the Empire that was the same size as the Empire and coincided precisely with it.”13Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science” in A Universal History of Infamy, trans. Norman Thomas de Giovanni (London: Penguin Books, 1975).

Sooner rather than later, we recognize the impossibility of recuperating and representing mail art; we leave knowing that each mailing nourished the network and that, with each mailing, it mutated. It had, one can only suppose, almost an infinite number of forms.

I recall Heraclitus’s river that we may never step into twice.

I think of time, and I will not extend this account.

Better to return to the ensemble of works and to the essays of those who study them.

Nevertheless, I suggest that mail art was. A beautiful interstice.

I hold that the works are (pardon the horrible metaphor) the remains of the cadaver.

Keep on Thinking

Mail art has ceased to exist. But the masters have spoken.

Just now I thought of the works as remains of a cadaver, and I am going to correct myself. The works are its memory. Their words speak to us even so, and in them we can hear the ocean.

I extend the invitation of an enlightened blind man: magister dixit (the master has spoken). This doesn’t mean that we need to repeat or imitate what the master has said; on the contrary, we need to take the liberty to continue to think the initial thought of the master.

As for us who now go into the river, it is our turn to keep on thinking. To fulfill the time of beauty. To continue thinking. And to stop.

Lea el texto en español aquí.

- 1Ulises Carrión’s “El Nuevo Arte de Hacer Libros” (The New Art of Making Books) was published in Plural (n. 41) in 1975 and appeared in English in Kontexts 6 and 7 that same year. The essay is available online in Spanish and in English. Martha Hellion has studied and gathered the artist’s work and coordinated Ulises Carrión: ¿Mundos personales o estrategias culturales? (Ulises Carrión: Personal Worlds or Cultural Strategies? (Mexico City: Turner, 2002).

- 2There’s a saying in Mexico that goes “everything fits in a jar if you organize it well.”

- 3In 1967, the artists Clemente Padín, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Guillermo Deisler, and Dámaso Ogaz, who were based in Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and Venezuela, respectively, were also the editors of publications focusing on Latin American experimental poetry and mail art. In 1967, they began an exchange, by mail, of their individual journals: Los Huevos del Plata (Padín), Diagonal Cero (Vigo), Ediciones Mimbre (Deisler), and La Pata de Palo (Ogaz).

- 4Grace Glueck, “What Happened? Nothing,” New York Times, April 11, 1965.

- 5Ed Plunkett gave the New York Correspondance School its name in 1962. In a play on words, Johnson employed the terms “Correspondence” and “Correspondance “ interchangeably. Plunkett commented: “It never claimed to be an innovation. In any case, it meant something, to go back to a tradition going back to primordial times. Examples in which communication was an art form can be cited throughout history. Cleopatra had herself rolled into a carpet to be presented to Julius Cesar.” Art Journal, Spring 1977.

- 6Hundreds of people are thought to have died in the massacre, which took place ten days before the opening of the summer Olympics in Mexico City.

- 7The full title of the work is: Obra secretamente titulado Arriba y Adelante . . . y si no pues también (Work secretly titled Upwards and Onwards . . . whether you like it or not).

- 8In interviews, the artists have given contradictory dates. These discrepancies are reflected in published sources that we have consulted: an exhibition took place in 1974 and in 1979. We searched for writing in stone, as it were, to corroborate them; a paper, an invitation. But history is written as much as it is erased. Mail artists also wrote in sand.

- 9Guerrero, Mauricio, “El Arte Correo en México” (Masters Thesis, UNAM, 1990). Many of the artists discussed by Guerrero—as partially listed above—can be researched elsewhere; much information on mail art and the artists involved can be found on the Internet.

- 10Borges, Jorge Luis, “For a Version of the I Ching,” Translated by Robert Mezey, The New York Review of Books, June 11, 1992.

- 11César Espinoza and Araceli Zúñiga, La Perra Brava (Mexico City: UNAM, 2002).

- 12Ibid.

- 13Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science” in A Universal History of Infamy, trans. Norman Thomas de Giovanni (London: Penguin Books, 1975).