In this short essay on the writings of the Argentine experimental artist Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Vanessa Davidson, Shawn and Joe Lampe Curator of Latin American Art at the Phoenix Art Museum, explores how the artist positioned his mail art practice in three key texts. post has commissioned translations of these texts, now newly available in English.

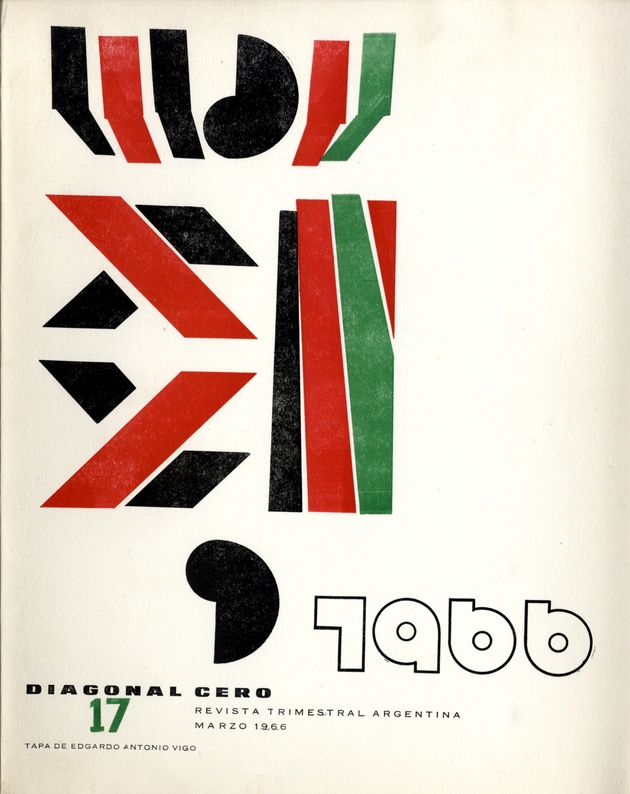

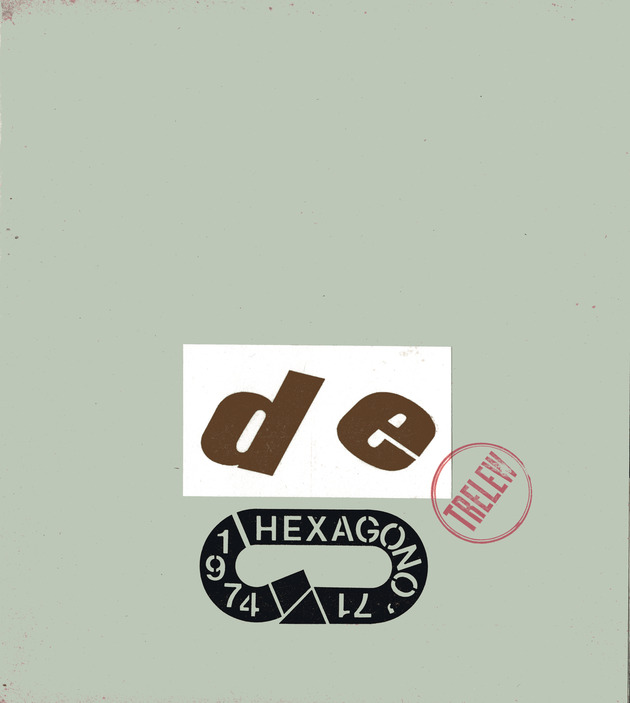

Edgardo Antonio Vigo (1928–1997) of La Plata, Argentina, was one of the preeminent pioneers of mail art in South America and the founder of this phenomenon in Argentina.1Vigo avoided the term “founder,” stating modestly, “At best, I am a guy who managed to create a source to be shared with friends and colleagues.” (A lo sumo, soy un tipo que pudo crear una fuente como para expresarla entre amigos y colegas.) Quoted in Eduardo Sívori, “El arte correo es una práctica alternativa que tiene adherentes en varios países del mundo,” La Maga (Buenos Aires), June 30, 1993. By day he worked in La Plata’s Ministry of Justice, while in his free time he was an editor of avant-garde magazines, a poet, a printmaker, a creator of Neo-Dada objects he called cosas (things), a performance artist, and a professor at La Plata’s Colegio Nacional. Vigo began his mail art activities in the mid-1960s, when he began sending “mathematical poems” to the French poet Julien Blaine and his circle. This circle soon widened to include artists from the United States, the Eastern Bloc countries, Japan, and all over Latin America. Vigo cultivated these contacts through the dissemination of his journals Diagonal Cero (1962–69) and Hexágono ’71 (1971–75). The latter, an “assembling” magazine composed of numerous artists’ mailings compiled by Vigo, was particularly effective in broadening his network of mail art colleagues, since contributions came in from around the world. Vigo’s diverse projects position him at the forefront of vanguard artistic activities in Argentina during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, although he rarely engaged with the avant-garde artistic scene centered in Buenos Aires during this time.

Doubly marginalized as a South American artist working in the small city of La Plata, which was, as he described, “known for its tranquility bordering on inertia,” a city “always betrayed by its large-town character,”2Vigo, “Carlos Alberto Pacheco,” Diagonal Cero 7,(September 1963). (Ciudad conocida por su tranquilidad rayana de la inercia . . . siempre desdecida por su carácter de pueblo-grande.) Vigo relied upon his mail art practice as a lifeline to artists around the globe. Yet, despite his leading role in the development of mail art in Latin America, he seems to have stumbled into its history almost by accident. As he expressed in a letter to the London-based artist Julia Tant on August 9, 1995: “The same thing happened to me as to you. I created envelopes for my mailings of exchanged materials, postcards, and stamps and used rubber stamps without knowing that since 1960 the SCHOOL OF CORRESPONDENCE founded by Ray Johnson—recently tragically disappeared—had begun to create the foundations for such practices.”3Vigo archive, La Plata, Argentina. All capitalizations in citations are original. (A mí me pasó lo mismo que a tí. Realizaba sobres para mis envios de intercambio de material, postales y estampillas y utilizaba los matasellos sin saber que desde 1960 la ESCUELA DE CORRESPONDENCIA fundada por Ray Johnson—recientemente desaparecido en forma trágica—había empezado a sentar las bases para desarrollar tal práctica.)

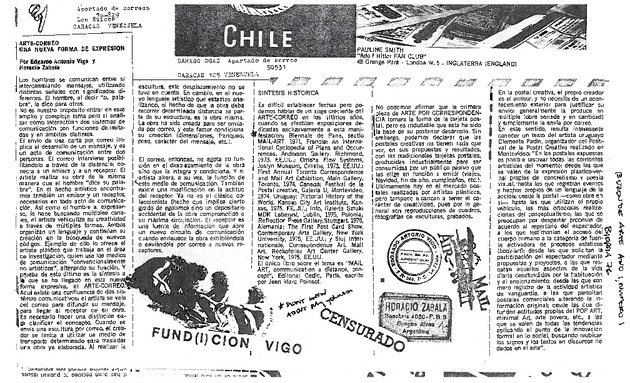

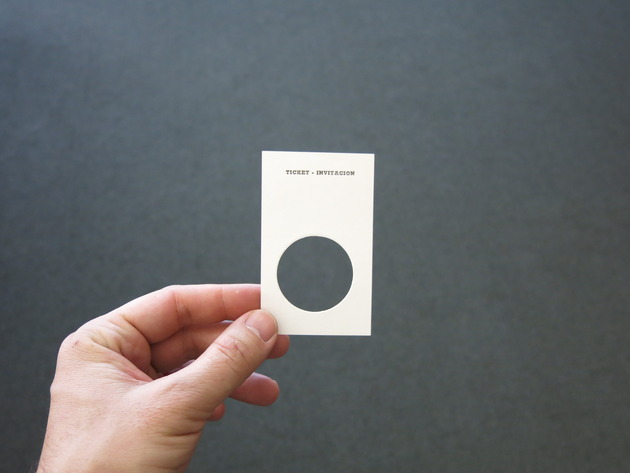

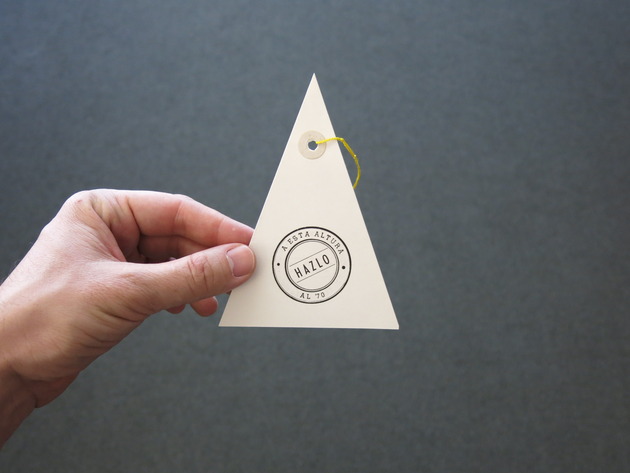

Vigo was one of the most prolific writers on mail art in Latin America. Three texts will be considered here, written in 1975, 1976, and 1981. Vigo’s first musings on mail art appear in a 1975 article titled “Arte-Correo: Una nueva forma de expresión” (Mail Art: A New Form of Expression). Written in collaboration with Argentine artist Horacio Zabala,4Horacio Zabala (1943–) is one of Argentina’s most important conceptual artists and was a member of the Grupo de los Trece, a cadre of thirteen artists formed around the CAYC (Centro de Arte y Comunicación) in Buenos Aires in the early 1970s. Although Zabala did not produce much mail art, in 1975 he collaborated with Vigo to organize the legendary Última exposición internacional de artecorreo (Last International Mail Art Show) at the Galería Arte Nuevo in Buenos Aires. This was, in fact, the first mail art exhibition in Argentina; 210 artists from 25 countries participated. this article was first published in 1975 in the magazine Poetas Argentinos and subsequently reprinted in January 1976 in the first issue of Venezuelan artist Diego Barboza’s broadsheet Buzón de Arte (Art Mailbox),5Diego Barboza (1945–) is a Venezuelan artist best known for his paintings and what he called “acciones poéticos,” or poetic actions, which fall under the rubric of performance art. He published only two issues of Buzón de Arte, both of which included texts by Vigo as well as by other international mail artists. and widely circulated in Latin America and beyond.6Edgardo Antonio Vigo and Horacio Zabala, “Arte-correo, una nueva forma de expresión.” First published in Poetas Argentinos370 (September–October 1975); reprinted in Buzón de Arte 1 (January, 1976): unpaginated. The article frames the definition of mail art in terms of two complementary operations. First, by creating works intended for mailing, mail artists co-opt the postal system as an aesthetic space and alter its “conventionally not artistic” character. Second, this space newly appropriated for art becomes an integral part of the works at a structural level, conditioning both their creation and their reception. According to Vigo and Zabala, mail art also fundamentally alters the role of the “receiver,” who becomes an “incidental custodian” of the work, as well as a “source of information” upon sending works to third parties or including them in exhibitions. The authors make a useful distinction between mailed art (such as a finished sculpture transported through the postal system) and mail art (pieces destined for mailing from their inception, in which “the fact that the work must travel a set distance is part of its structure, is the work itself”).7Ibid. (. . . el hecho de que la obra deba recorrer determinada distancia es parte de su estructura, es la obra misma.) In the remainder of the article, they list numerous mail art shows from around the world. Their omission of the activities of the New York Correspondence School and of Fluxus during the first half of the 1960s manifest their incomplete knowledge of international events.

Vigo titled his subsequent text on mail art “Artecorreo: Una nueva etapa en el proceso revolucionario de la creación” (Mail Art: A New Phase in the Revolutionary Process of Creation). Dated January 1976, this article was published in the second issue of Buzón de Arte, in March 1976.8Edgardo Antonio Vigo, “Artecorreo: Una nueva etapa en el proceso revolucionario de la creación,” Buzón de Arte Año 1, no. 2, March, 1976. The manuscript of a longer version of this text, discovered in Vigo’s archive, alludes to Fluxus as “the movement that for the first time made postal practice an element of creative communication,” and mentions Ray Johnson, Arman, Robert Filliou, and Chieko Shiomi as precursors. Here, Vigo anchors mail art practice in the writings of Jean-Marc Poinsot and the theories of Baudrillard in order to address the relationship between this art and the mass media. He underscores the notion that the impossibility of any personal response to communications received via mass media makes “REAL INTERCOMMUNICATION” a “NECESSARY NECESSITY.” He then positions mail art in the context of “AN ALTERNATIVE HISTORY OF ART,” also emphasizing its practitioners’ committed resistance to the “siren song” of museums, galleries, and commercial art venues. Perhaps the most revelatory aspect of this article is Vigo’s insistence on the sociopolitical potential of mail art. He calls for mail artists to be revolutionary by “CONTAINING WITHIN THEIR MESSAGES the appropriate dose of inconformity, subversion, and both international and private relationships that turn them into a CRITICAL TESTIMONY OF ‘SOCIO-POLITICAL-ECONOMIC’ REALITIES, creating the means of eluding the “Official,” the principal agent of all the traps and difficulties imposed upon Creation.”9Ibid. (. . . y por CONTENER algunos de sus mensajes la suficiente dosis de inconformismo, subversión y relaciones globales y particulares que lo convierten en TESTIMONIO CRÍTICO DE LAS REALIDADES ‘SOCIOPOLÍTICOECONOMICO,’ creando las formas de eludir a lo ‘Oficial,’ principal agente productor de todas las trampas y dificultades impuestas a la Creación.)

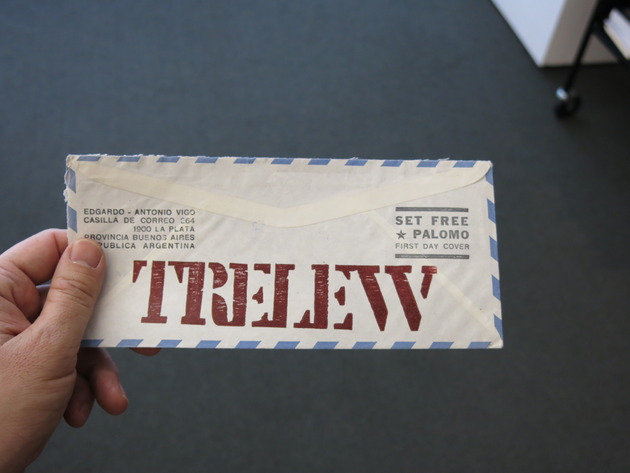

This call to arms reflects the revolutionary spirit of the times in Argentina. It is not, however, an about-face for Vigo: his growing political engagement can be charted both in his magazines and in his mail art over the course of the early to mid-1970s, as the violent tensions that would lead to General Jorge Rafael Videla’s 1976 military coup reached a fever pitch. But Vigo’s very personal connection to Argentina’s sociopolitical crisis—the “disappearance” of his son Abel Luis “Palomo” Vigo, who was taken by the military police in July, 197610Vigo described his eldest son’s abduction in “Algunas luchas políticas latinoamericanas a través de la comunicación-a-distancia” (Some Latin American Political Struggles by means of Long-Distance Communication), an unpublished manuscript found in his archive. “Abruptly, an armed group—[which I later learned] belonged to the Argentine military—burst into my house in the small hours of July 30, 1976. Stifling my protest by force, covering my head with a bag in an effort to silence my compromising testimony, they took him from my home.” (De manera abrupta un grupo armado—por datos posteriores pertenecientes al ejército argentino—irrumpió en mi casa la madrugada del 30 de julio de 1976. Acallada mi protesta por la fuerza, cubriéndome la cabeza con un saco en un intento de silenciar mi testimonio comprometedor, lo retiraron de mi domicilio.)—would color all aspects of his production for years afterward. Palomo was never recovered; he joined the list of the estimated 30,000 people who disappeared between 1976 and 1983, during Argentina’s “dirty war.”

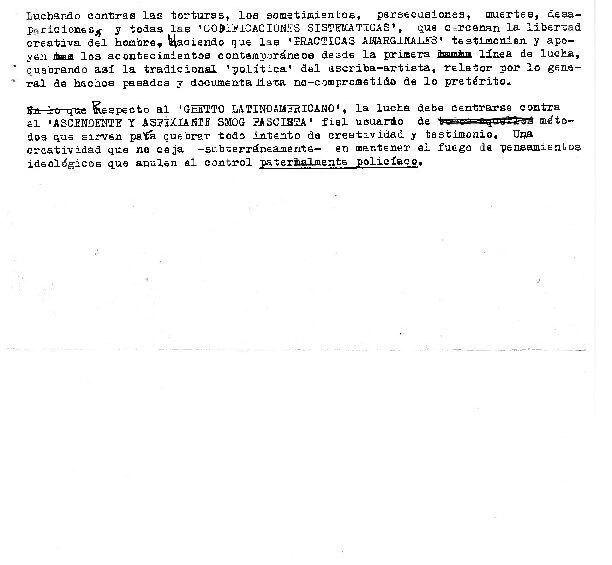

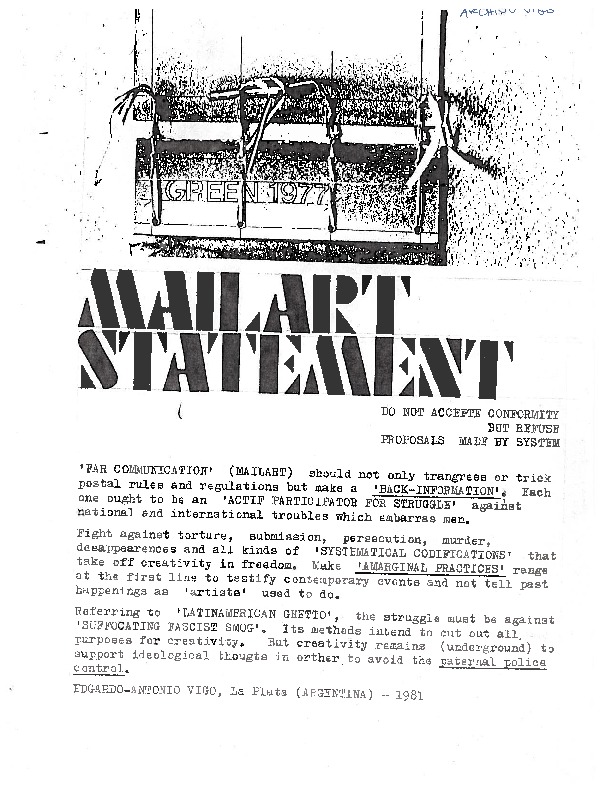

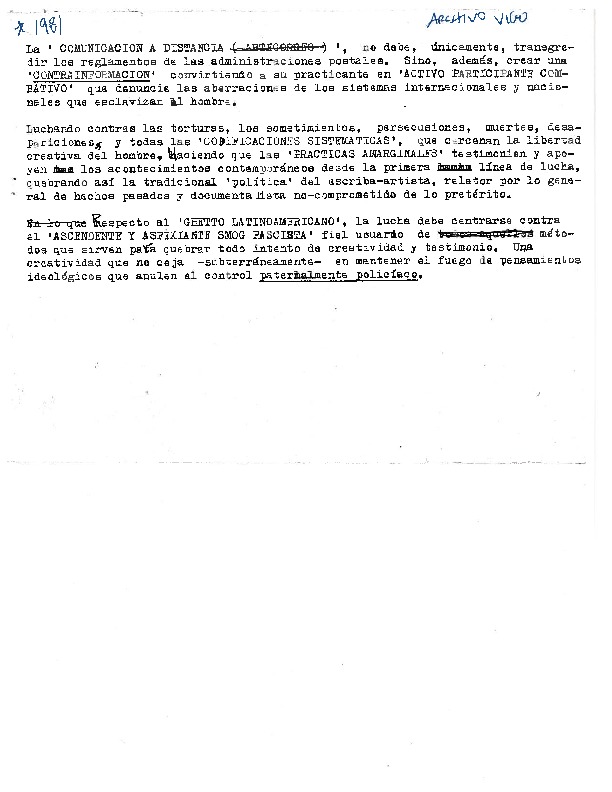

The final text considered here, Vigo’s 1981 “Mail Art Statement,”11Vigo himself translated his original Spanish text into English, with many confusing errors. For purposes of clarity of intent, his original Spanish text, which was discovered in his archives in 2008, is referenced here. clearly elucidates the author’s politics, and by extension the political potential of mail art. Subtitled “DO NOT ACCEPTE [sic] CONFORMITY BUT REFUSE PROPOSALS MADE BY SYSTEM,” this text was never published but instead circulated through the postal network along with works of mail art. Beyond transgressing postal regulations, Vigo argues, mail artists should take a militant stance, becoming “ACTIVE COMBATIVE PARTICIPANTS” on the front lines of the fight against persecution and the violation of basic human rights. In the “LATIN AMERICAN GHETTO,” this battle should be waged against the “RISING AND SUFFOCATING FASCIST SMOG,” a term that handily evokes the pervasive climate of terror under oppressive military dictatorships. Although such forces try in vain to quash creativity, the “underground” continues to thrive, Vigo asserts, keeping “alive the fire of ideological thoughts that nullify paternalistic police control.”

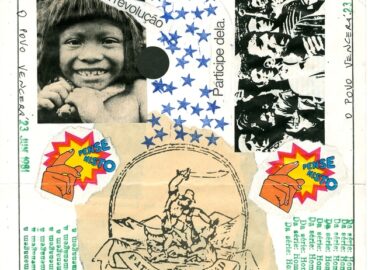

Vigo’s writings on mail art from 1975, 1976, and 1981 effectively mirror the rising tide of revolutionary fervor to which he was a witness and in which he himself participated. While he sent news of the Argentine people’s plight through the international mail art network, his own strategies of resistance hinged on the clandestine operations of the underground. As evidenced in his archives in La Plata, his urgent calls for solidarity were answered by artists around the world. The escalation of political rhetoric that can be charted in these texts reflects Vigo’s own increasing outrage at the rapid deterioration of Argentina’s social fabric as a result of clashes between military and paramilitary troops, and his insistence on accountability for his nation’s descent into chaos and terror.

Vigo’s decision to use the mail as a vehicle for his work was political in and of itself. Mail art, the most democratic of art forms, predicated on principles of international collaboration and exchange, could be practiced by professional and amateur artists alike. Vigo embraced this medium as a means of circumventing both institutional and commercial art circuits vulnerable to censorship and as a powerful instrument for making his voice heard far beyond La Plata during the darkest era of his nation’s history. As Fluxus and mail artist Ken Friedman expressed in an interview: “Edgardo Antonio Vigo seems to me to be one of the important figures in mail [art]. His work had political dimensions in a difficult time and place that made it the voice—and for many people—the face of mail art from artists who lived in nations governed by right-wing dictatorships.” Further, Friedman continues: “Vigo was an extraordinary human being and an important artist in a time that made extraordinary art difficult. Simply to function as a voice, simply to survive in his situation while remaining connected to the world outside, was heroic. In this sense, I admired his work and respected his spirit . . . .”12Email from Ken Friedman to the author, April 25, 2011.

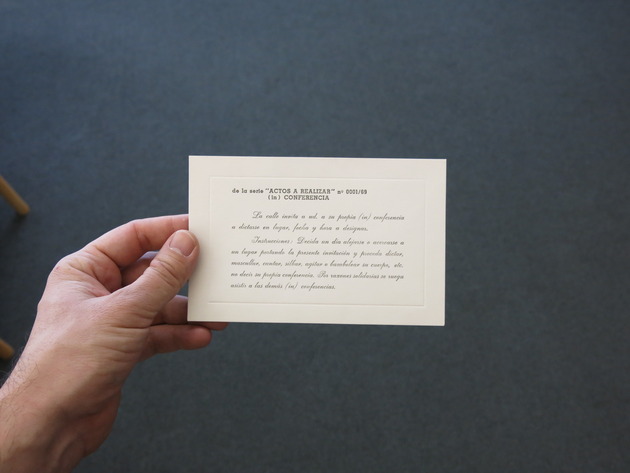

Vigo continued to create mail art for the rest of his life, and he helped others to join the network by sharing addresses and exhibition invitations. The great variety of his production is remarkable, as is the breadth of his contacts within and outside Latin America. Despite the hardships he suffered, he never lost his passionate commitment to mail art as a vital system for connecting and collaborating with like-minded artists living worlds away. As he wrote in his diary:

Perhaps the practice of MAILART will not bequeath to the future a different means for giving dimension to reality, but we recognize within it the possibility of a NEW CIRCUIT of communication at a distance. MAILART has effected connections between international marginalities, the expansion of their interchanges, the distribution of their multiples, the exchange or the polemics of their theories, inviting profound dialogue.13From Vigo’s diaries, Vigo archive. (Quizás no sea la práctica del MAILART la que legue al futuro la transmisión diferente de dimensionar la realidad, pero reconocemos en éste la posibilidad de un NUEVO CIRCUITO de comunicación a distancia. El MAILART ha producido el contacto de las marginalidades internacionales, la ampliación de sus intercambios, la distribución de sus múltiples, el canje o la polémica de sus teorías, invitando al diálogo profundo.)

For Vigo, art was life, and mail art, a potent means for connecting with the world beyond La Plata.

He marshaled his geographic marginality into part of a tactical, political stance centered on the dissolution of boundaries between the center and the periphery, the international and the local, privileging art created and circulated outside official infrastructures. The “cry of freedom” Vigo mentions repeatedly as the basis of his mail art practice is present throughout his varied works, which, despite being crafted on the margins of the international art world, journeyed and made their messages heard around the globe.

- 1Vigo avoided the term “founder,” stating modestly, “At best, I am a guy who managed to create a source to be shared with friends and colleagues.” (A lo sumo, soy un tipo que pudo crear una fuente como para expresarla entre amigos y colegas.) Quoted in Eduardo Sívori, “El arte correo es una práctica alternativa que tiene adherentes en varios países del mundo,” La Maga (Buenos Aires), June 30, 1993.

- 2Vigo, “Carlos Alberto Pacheco,” Diagonal Cero 7,(September 1963). (Ciudad conocida por su tranquilidad rayana de la inercia . . . siempre desdecida por su carácter de pueblo-grande.)

- 3Vigo archive, La Plata, Argentina. All capitalizations in citations are original. (A mí me pasó lo mismo que a tí. Realizaba sobres para mis envios de intercambio de material, postales y estampillas y utilizaba los matasellos sin saber que desde 1960 la ESCUELA DE CORRESPONDENCIA fundada por Ray Johnson—recientemente desaparecido en forma trágica—había empezado a sentar las bases para desarrollar tal práctica.)

- 4Horacio Zabala (1943–) is one of Argentina’s most important conceptual artists and was a member of the Grupo de los Trece, a cadre of thirteen artists formed around the CAYC (Centro de Arte y Comunicación) in Buenos Aires in the early 1970s. Although Zabala did not produce much mail art, in 1975 he collaborated with Vigo to organize the legendary Última exposición internacional de artecorreo (Last International Mail Art Show) at the Galería Arte Nuevo in Buenos Aires. This was, in fact, the first mail art exhibition in Argentina; 210 artists from 25 countries participated.

- 5Diego Barboza (1945–) is a Venezuelan artist best known for his paintings and what he called “acciones poéticos,” or poetic actions, which fall under the rubric of performance art. He published only two issues of Buzón de Arte, both of which included texts by Vigo as well as by other international mail artists.

- 6Edgardo Antonio Vigo and Horacio Zabala, “Arte-correo, una nueva forma de expresión.” First published in Poetas Argentinos370 (September–October 1975); reprinted in Buzón de Arte 1 (January, 1976): unpaginated.

- 7Ibid. (. . . el hecho de que la obra deba recorrer determinada distancia es parte de su estructura, es la obra misma.)

- 8Edgardo Antonio Vigo, “Artecorreo: Una nueva etapa en el proceso revolucionario de la creación,” Buzón de Arte Año 1, no. 2, March, 1976. The manuscript of a longer version of this text, discovered in Vigo’s archive, alludes to Fluxus as “the movement that for the first time made postal practice an element of creative communication,” and mentions Ray Johnson, Arman, Robert Filliou, and Chieko Shiomi as precursors.

- 9Ibid. (. . . y por CONTENER algunos de sus mensajes la suficiente dosis de inconformismo, subversión y relaciones globales y particulares que lo convierten en TESTIMONIO CRÍTICO DE LAS REALIDADES ‘SOCIOPOLÍTICOECONOMICO,’ creando las formas de eludir a lo ‘Oficial,’ principal agente productor de todas las trampas y dificultades impuestas a la Creación.)

- 10Vigo described his eldest son’s abduction in “Algunas luchas políticas latinoamericanas a través de la comunicación-a-distancia” (Some Latin American Political Struggles by means of Long-Distance Communication), an unpublished manuscript found in his archive. “Abruptly, an armed group—[which I later learned] belonged to the Argentine military—burst into my house in the small hours of July 30, 1976. Stifling my protest by force, covering my head with a bag in an effort to silence my compromising testimony, they took him from my home.” (De manera abrupta un grupo armado—por datos posteriores pertenecientes al ejército argentino—irrumpió en mi casa la madrugada del 30 de julio de 1976. Acallada mi protesta por la fuerza, cubriéndome la cabeza con un saco en un intento de silenciar mi testimonio comprometedor, lo retiraron de mi domicilio.)

- 11Vigo himself translated his original Spanish text into English, with many confusing errors. For purposes of clarity of intent, his original Spanish text, which was discovered in his archives in 2008, is referenced here.

- 12Email from Ken Friedman to the author, April 25, 2011.

- 13From Vigo’s diaries, Vigo archive. (Quizás no sea la práctica del MAILART la que legue al futuro la transmisión diferente de dimensionar la realidad, pero reconocemos en éste la posibilidad de un NUEVO CIRCUITO de comunicación a distancia. El MAILART ha producido el contacto de las marginalidades internacionales, la ampliación de sus intercambios, la distribución de sus múltiples, el canje o la polémica de sus teorías, invitando al diálogo profundo.)