Jaider Esbell was a pioneering artist, enabler, and advocate of Indigenous perspectives, environmentalism, and land rights. In this essay, Madeline Murphy Turner analyzes recent artworks by the late Macuxi artist, and contextualizes his artistic and activist practice in the wider landscape of critical Indigenous representation in the Americas.

In fall 2021, while working as the Cisneros Institute Research Fellow, I had the privilege of speaking with Macuxi artist Jaider Esbell (1979–2021) over Zoom. Our conversation was brief, but with the assistance of his trusted collaborators Paula Berbert and Daniel Jabra, we organized a much anticipated virtual studio visit that was scheduled to take place on November 3.1I am immensely grateful to Paula Berbert and Daniel Jabra for their support and feedback on this text. The day before our planned meeting, Jaider Esbell passed away.

Esbell’s premature departure coincided with a moment of heightened visibility and well-deserved recognition of his practice. When I had the chance to travel to São Paulo just two weeks later, his significant impact on the programs within major art institutions throughout the city—the Bienal de São Paulo, the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, and the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM), among others—was immediately tangible, even to an outsider such as myself. In every artistic sphere I encountered, his presence, ideas, and legacy were deeply felt.

Born in Brazil on Indigenous territory known today as Terra Indígena Raposa Serra do Sol, which borders Guyana and Venezuela, Esbell had already participated in a number of Indigenous social movements by the time he moved to the city of Boa Vista at the age of eighteen. In 2011, he began to immerse himself more profoundly in the visual realm when he held an exhibition titled Cabocagem—O homem na paisagem (Cabocagem—man in the landscape), in which he presented fifteen of his own artworks. Two years later, he organized the first edition of Encontro de Todos os Povos (Meeting of All People), establishing himself as an advocate for Indigenous artists and making clear the living presence of their culture and art. Moreover, these efforts promoted a specific Macuxi worldview, which importantly includes Makunaimî, who the Macuxi, Taurepang, and Wapichana peoples consider to be the creator of all natures.2Naine Terena, Véxoa: Nós sabemos, exh. cat. (São Paulo: Pinacoteca de São Paulo, 2020), 78. “To be an Indigenous artist, from my perspective,” Esbell explained in a 2019 interview, “is to claim through these four letters—A R T E [art]—everything that it connects us to in terms of possibilities and bridging, indeed, worlds.” He continued, “It is a very special condition that we have been able to attain to be able to make small fissures between worlds so that this communication, which academia has been handling for a very long time, may have more fluidity.”3Jaider Esbell, interview by Carlos Fausto, Amazonian Poetics/Poéticas Amazônicas, Brazil LAB/Princeton University & Museu Nacional/UFRJ workshop, Princeton University, November 8, 2019, YouTube video, 2:06, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oDCondf3kVM&t=28s.

Esbell maintained a diverse practice, one that spanned the roles of writer, poet, art educator, curator, and activist. Committed to art as a form of pedagogical activism—or artivism as he called it—he brought together painting, writing, drawing, installation, and performance to elaborate on transversal dialogues with Indigenous cosmologies, environmental concerns, land rights, and critiques of hegemonic culture.4Oliver Basciano, “An Ancient Vision for a New Art: Jaider Esbell (1979–2021),” ArtReview 73, no. 6 (October 2021): 83. Through his work, he promoted Arte Indígena Contemporânea (Contemporary Indigenous Art),5“Moquém_Surarî: Arte indígena contemporânea,”Artishock: Revista de arte contemporaneo, posted September 21, 2021, https://artishockrevista.com/2021/09/21/moquem_surari-arte-indigena-contemporanea/. making explicit the importance of contemporary Indigenous artists—especially women—in order to actively contradict the oppressive and violent Western institutional structures that locate Indigenous art and culture in the past.

Esbell’s prominence in the 34th edition of the Bienal de São Paulo, Faz escuro mas eu canto (Though It’s Dark, Still I Sing), held in 2021, was evident. Among other works, he exhibited Entidades (Entities, 2021) [Figs. 1–2], a seventeen-meter inflatable sculpture that greeted visitors as they approached the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, headquarters of the Bienal de São Paulo Foundation since 1957 and a key Bienal venue.6A related version of this sculpture was simultaneously on view 100 kilometers away in Sorocaba as part of the Frestas Trienal de Artes. See https://frestas.sescsp.org.br/en/. Creating two colorfully marked serpents—creatures the Macuxi understand to be powerful agents of transformation—Esbell intended for the work to confront the nearby statue of Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral, credited in Western history with the “discovery” of Brazil in 1500, despite the fact the territory and its people were existing and thriving long before his arrival.7Paula Berbert and Daniel Jabra in conversation with the author, April 16, 2022. Esbell’s critique of hegemonic discourse further extends through the sculpture’s dialogue with the Pavilion, which was designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer within the context of Brazil’s mid-twentieth-century bid for international recognition through the language of Modernist architecture.8For more on this topic, see Adele Nelson, Forming Abstraction: Art and Institutions in Postwar Brazil (Oakland: University of California Press, 2022). See also Luis E. Carranza and Fernando Luiz Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014). Entidades emerged from a significantly less recognized and yet crucial history of Brazilian art, one frequently erased in favor of Modernist or Western ideals. It and other works presented by Esbell at the Bienal directly engage mythologies and origins outside the narrative of European Christianity.9“Jaider Esbell (1979–2021),” Artforum, November 3, 2021, https://www.artforum.com/news/jaider-esbell-1979-2021-87142.

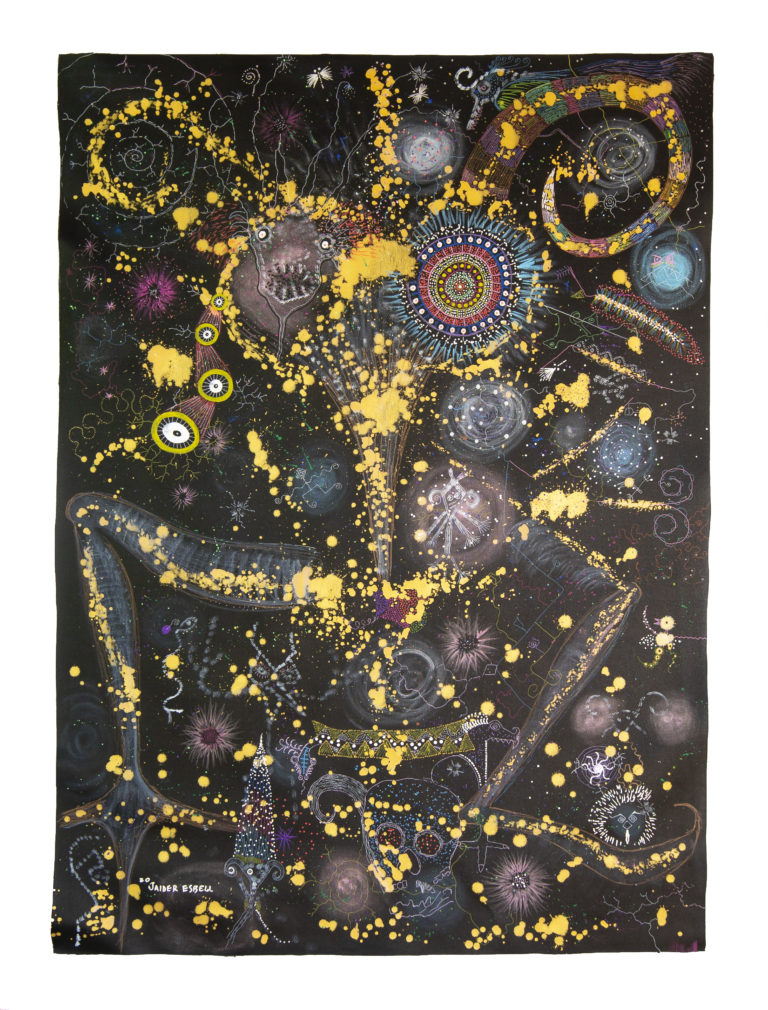

Highlighting Macuxi worldviews and their ongoing relevance, Esbell painted A guerra dos Kanaimés (War of the Kanaimés, 2019/20) [Figs. 3–6], a series of vibrant yet caliginous paintings that were on view inside the Pavilion.10The 34th edition of the Sao Paulo Biennial was curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, Paulo Miyada, Carla Zaccagnini, Francesco Stocchi, and Ruth Estévez. A guerra dos Kanaimés was also included in the exhibition Vento (Wind), which was held in the São Paulo Biennial Pavilion from November 14 through December 13, 2020. Invoking the Kanaimés, deadly spirits usually associated with violence, the artist references the cosmovision of the Macuxi people in order to ground the fear associated with the Kanaimés in a concrete and contemporary context: Indigenous peoples’ right to life and land in defiance of attempts to exploit their territory. This critical series must be considered in relationship to the numerous resistance movements formed to fight for Indigenous land rights. In 2021, for example, more than 170 distinct peoples from across Brazil went to the nation’s capital to oppose proposed legislation that would both displace them and open their land to deforestation.11“Bill 490/2007 . . . would prevent Indigenous peoples from obtaining legal recognition of their traditional lands if they were not physically present there on October 5, 1988—the day Brazil’s Constitution was enacted—or if they had not initiated legal proceedings to claim it by that date.” “Brazil: Reject Anti-Indigenous Rights Bill: Proposal a Major Setback to Land Rights Recognition,” Human Rights Watch website, posted August 24, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/08/24/brazil-reject-anti-indigenous-rights-bill. As of December 2021, the Supreme Court of Brazil has indefinitely shelved the case. While some activists have found success in their efforts to legally defend their territory, others have been targeted—especially Indigenous peoples, who are frequently at the forefront of land disputes and environmental activism. Esbell also brought this activism into the Bienal’s public sphere with the intervention Cortejo de enunciado da Bienal dos Índios (Indigenous Biennial Announcement Procession) [Figs. 7–9], which he performed in collaboration with his partner and fellow artist and activist Daiara Tukano, among other Indigenous activists and artists, including Gustavo Caboco, during the opening in September 2021. As they processed through the Pavilion, they paused at works by Sueli Maxakali, Uýra, and Caboco, as well as their own to stress that five Indigenous artists were represented in the exhibition—the most in the Bienal’s seventy-year history.

Of equal significance is the fact that two recent exhibitions in São Paulo have been dedicated exclusively to Indigenous art: Véxoa: Nós sabemos (Véxoa: We Know), curated by Naine Terena for the Pinacoteca de São Paulo in 2020, and Moquém_Surarî: Arte indígena contemporânea (Moquém_Surarî: Contemporary Indigenous Art), curated by Esbell for the MAM the following year. The former brought together more than twenty Indigenous artists and artist collectives, including Esbell, to confront the challenges Indigenous art faces today. Speaking to the attempted erasure of Indigenous art from Brazilian culture since the beginning of colonization, Terena writes: “The ‘whitening’ of art in Brazil is similar to the whitening of its population, where both alien and foreign references are overestimated to the detriment of indigenous and national ones. The aesthetic concept of art was brought to the country in the luggage of the colonizers. The strength of the internal production of a great diversity of indigenous peoples and their cultural manifestations were not recognized for their artistic qualities or when they were, they were mainly taken as an inspiration or reference for the art of the non-indigenous people.”12Naine Terena, “Véxoa: We Know,” in Véxoa: Nós sabemos, 13–14.

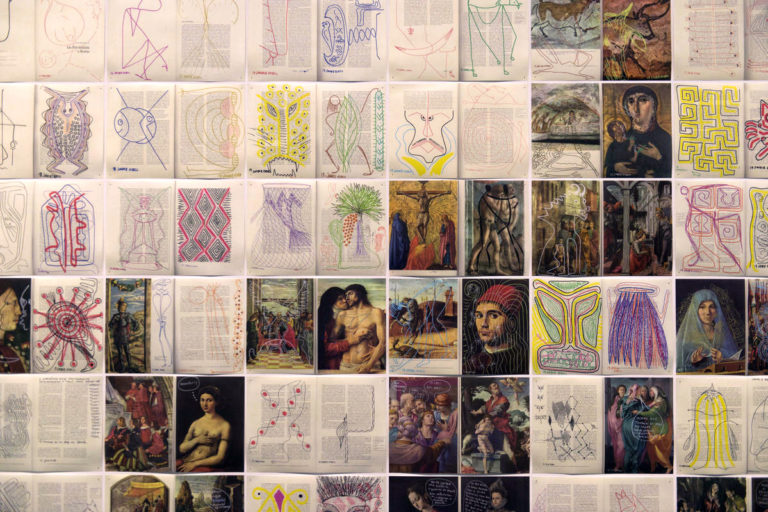

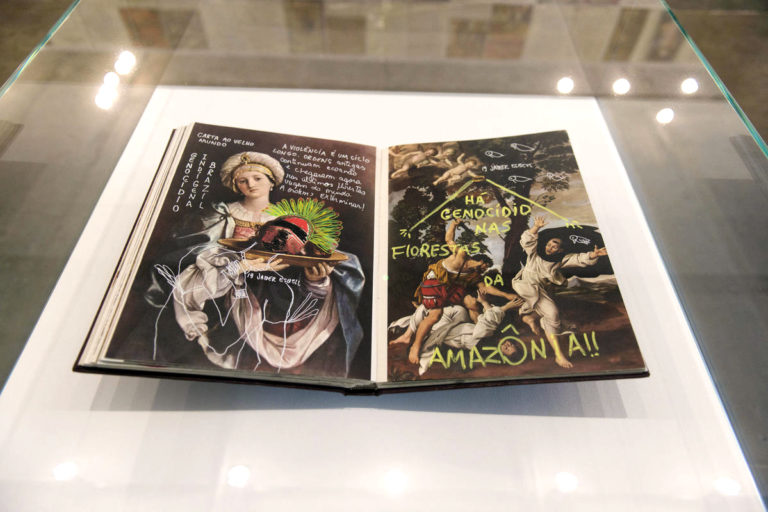

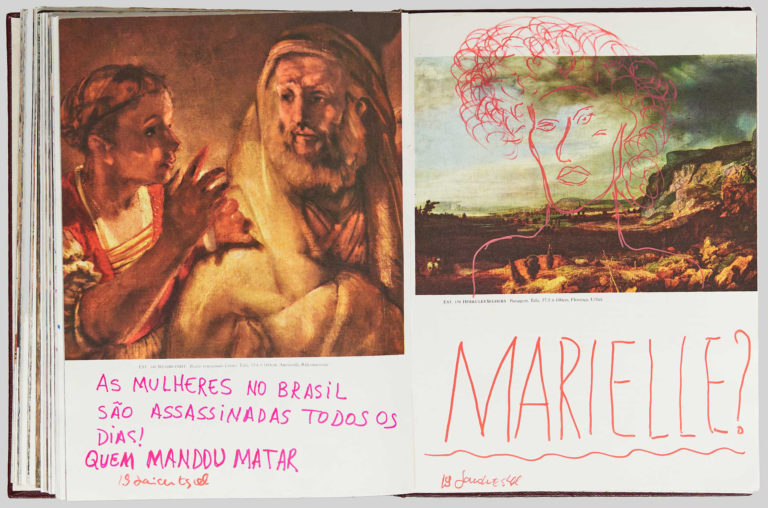

Through his artistic, activist, and pedagogical work, Esbell criticized this erasure, or “whitening,” as Terena argues, of art. Carta ao velho mundo (Letter to the Old World, 2019) [Fig. 10], exemplifies Esbell’s concurrent commitment to visual practice and social engagement. Offering a counternarrative to hegemonic history, the large-scale installation features Esbell’s interventions onto pages torn from a four-hundred-page tome dedicated to Western art. By drawing over reproductions of paintings by Diego Velázquez and Caravaggio, among others, or images of the Virgin Mary, Venus, and other hallmarks of a “traditional” art education, Esbell inserted his own commentary, exposing the oppressiveness of this constructed historical narrative. For example, on a reproduction of the painting The Martyrdom of Saint Peter (c. 1620) by Italian Baroque painter Domenichino, Esbell intervened with his signature acrylic marker, drawing small birds into the trees and writing “Há genocídio nas florestas da Amazônia!!” (There is genocide in the Amazon forests!!) [Fig. 11]. On a page dedicated to a seventeenth-century landscape painting by Dutch Golden Age artist Hercules Seghers, Esbell sketched a portrait of Marielle Franco, the queer, Afro-Latina, feminist politician and human rights activist whom the Rio de Janeiro police assassinated in 2018 in a case of government corruption [Fig. 12]. Below her image, Esbell asks, “Marielle?,” evoking the question “Who killed Marielle?,” which was commonly inscribed on posters during the protests that followed her murder. Esbell’s intervention into Western art history with references to Marielle and the destruction of the Amazon aims to expose the ways in which individuals who are not of European descent, from the United States, white, or Christian, are targeted yet excluded from the master narratives of human society. Carta ao velho mundo sheds light on how Eurocentric history—now part of the “Old World” as the title claims—has succeeded at the expense of those deemed to be outside the demographics mentioned above, especially those who challenge such power.

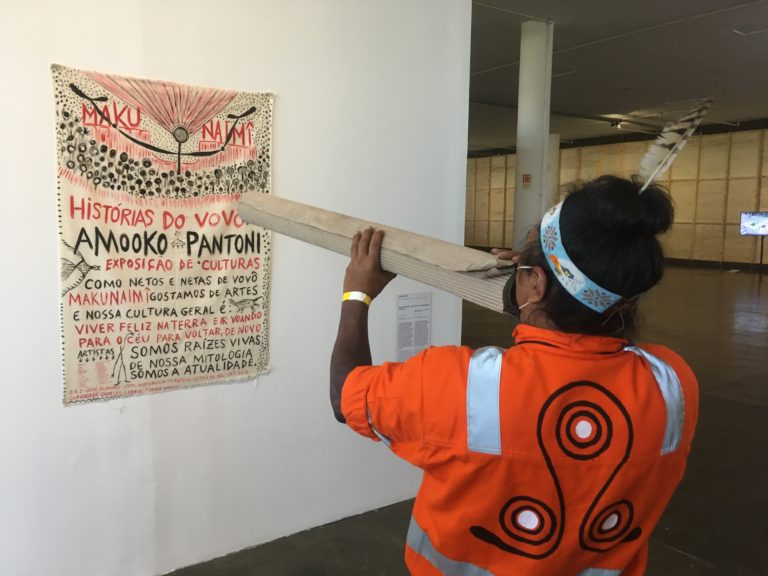

Though Carta ao velho mundo engages with what might be understood as the past, Esbell’s practice was embedded within various temporalities. Along with professor and artist Charles Gabriel, he collaborated with Macuxi children to instill the importance of arts education in future generations and as a method to dismantle hegemonic art historical pedagogies. Amooko Panton—Histórias do vovô Makunaimî (Amooko Pantoni—Stories of Grandpa Makunaimî, 2018) [Fig. 13], which was exhibited on the third floor of the Bienial Pavilion, is composed of thirty-two paintings that Macuxi youth created in collaboration with Esbell through a series of workshops led by Esbell and Gabriel at the José Alamano Indigenous State School in the Maturuca community of the Terra Indígena Raposa Serra do Sol. In these images, the children have depicted stories of the Macuxi people, demonstrating the living roots of their mythology. Esbell’s work as a cultural facilitator, furthermore, is intricately elaborated in Moquém_Surarî: Arte indígena contemporânea, which featured thirty-four Indigenous artists including Daiara Tukano, Rita Sales Huni Kuin, and Elisclésio Makuxi [Fig. 14]. On view at the MAM, adjacent to the Bienal Pavilion, this exhibition seemed to expand on the presentation of the five indigenous artists in Faz escuro mas eu canto, showing the present impact of Indigenous visual practice—as in Rita Sales Huni Kuin’s paintings, which unfold the relationship between ritual action and aesthetic experience through a rich iconography of symbols that intertwine animals, plants, and people.

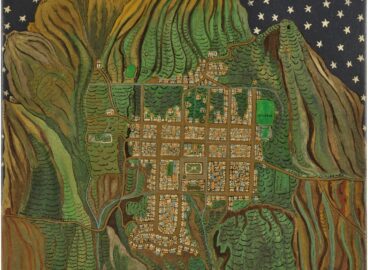

Although the emphasis on the work of Indigenous artists in biennials and temporary exhibitions has and will be analyzed by some as simply the result of fleeting, Eurocentric institutional interest in “otherness,” I would argue that the permanence of this shift is evidenced by the reimagination of the collection galleries of the Pinacoteca de São Paulo. Reopened in October 2020 to coincide with the inauguration of Véxoa: Nos sabemos, the new installation and corresponding pedagogical information directly address the legacy of colonialism in Brazil as well as grapple with the omissions that characterize hegemonic narratives. Esbell’s Feitiço para salvar a Raposa Serra do Sol (Spell to Save the Raposa Serra do Sol, 2019), is located in one of the new galleries, Terra como matéria (Land as Subject), which questions the Western-imposed understanding of the human-nature relationship as one of anthropocentric domination, in favor of a worldview that prioritizes a reciprocal relationship between humans and nonhumans.13For more about the relationship between Indigenous people and ancestral land, see Ailton Krenak, Ideas to Postpone the End of the World, trans. Anthony Doyle (Toronto: Anansi Press, 2020). For more on the intrinsic value of nature, see Eduardo Gudynas, Derechos de la naturaleza: Ética biocéntrica y políticas ambientales (Lima: Programa democracia y transformación global, 2014). With this presentation, Indigenous artists are making their way into the galleries of well-funded institutions. Still, it is clear that these very institutions are questioning their own histories and the violence their narratives have enacted on large populations of individuals.

At the time I traveled to São Paulo, the art world was still grieving, both privately and publicly, Esbell’s unexpected passing. Denilson Baniwa, Esbell’s close friend and colleague, asked that his own work, which was on view in several venues, be covered for an indefinite period. In response, the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), the Pinacoteca, the MAM (in Moquém_Surarî: Arte indígena contemporânea), and other institutions shrouded Baniwa’s artwork in black cloth [Fig. 15]. A gesture to Esbell’s absence, Baniwa’s request also signals the impossible and perhaps even destructive weight that Indigenous artists today carry in fighting for not just representation, but also understanding and respect through increased visibility. In a public letter written on November 3, 2021, Baniwa stated that together, he and Esbell were committed to creating pathways for indigenous expression, but emphasized that with Esbell’s death, he would have to reconsider his own relationship with the West.14Adriano Pedrosa read Baniwa’s letter in an introduction to “the fourth seminar in a long-term project that anticipates MASP’s 2023 program of exhibitions, lectures, workshops, publications, and courses dedicated to Indigenous Histories,” streamed live on November 9, 2021, YouTube video, 6:04:25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9o4rlMfSadA.

Exhibitions and biennials come and go, but what is evident is that Jaider Esbell’s profound work will continue to weave its way through and beyond the Brazilian art world. His life and practice demonstrate, however, the immense challenges that still face Indigenous peoples and the art institutions that attempt to present their art. As Esbell’s life project clarifies, buying and collecting Indigenous art is insufficient. There needs to be a deep investment in education, activism, and future generations of Indigenous artists, and a serious institutional reckoning with the immense harm caused by exclusionary collecting and exhibiting practices. In this sense, the work must simultaneously consider multiple temporalities—past, present, and future—to begin creating the small fissures for which Esbell so eloquently advocated.

- 1I am immensely grateful to Paula Berbert and Daniel Jabra for their support and feedback on this text.

- 2Naine Terena, Véxoa: Nós sabemos, exh. cat. (São Paulo: Pinacoteca de São Paulo, 2020), 78.

- 3Jaider Esbell, interview by Carlos Fausto, Amazonian Poetics/Poéticas Amazônicas, Brazil LAB/Princeton University & Museu Nacional/UFRJ workshop, Princeton University, November 8, 2019, YouTube video, 2:06, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oDCondf3kVM&t=28s.

- 4Oliver Basciano, “An Ancient Vision for a New Art: Jaider Esbell (1979–2021),” ArtReview 73, no. 6 (October 2021): 83.

- 5“Moquém_Surarî: Arte indígena contemporânea,”Artishock: Revista de arte contemporaneo, posted September 21, 2021, https://artishockrevista.com/2021/09/21/moquem_surari-arte-indigena-contemporanea/.

- 6A related version of this sculpture was simultaneously on view 100 kilometers away in Sorocaba as part of the Frestas Trienal de Artes. See https://frestas.sescsp.org.br/en/.

- 7Paula Berbert and Daniel Jabra in conversation with the author, April 16, 2022.

- 8For more on this topic, see Adele Nelson, Forming Abstraction: Art and Institutions in Postwar Brazil (Oakland: University of California Press, 2022). See also Luis E. Carranza and Fernando Luiz Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

- 9“Jaider Esbell (1979–2021),” Artforum, November 3, 2021, https://www.artforum.com/news/jaider-esbell-1979-2021-87142.

- 10The 34th edition of the Sao Paulo Biennial was curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, Paulo Miyada, Carla Zaccagnini, Francesco Stocchi, and Ruth Estévez. A guerra dos Kanaimés was also included in the exhibition Vento (Wind), which was held in the São Paulo Biennial Pavilion from November 14 through December 13, 2020.

- 11“Bill 490/2007 . . . would prevent Indigenous peoples from obtaining legal recognition of their traditional lands if they were not physically present there on October 5, 1988—the day Brazil’s Constitution was enacted—or if they had not initiated legal proceedings to claim it by that date.” “Brazil: Reject Anti-Indigenous Rights Bill: Proposal a Major Setback to Land Rights Recognition,” Human Rights Watch website, posted August 24, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/08/24/brazil-reject-anti-indigenous-rights-bill. As of December 2021, the Supreme Court of Brazil has indefinitely shelved the case. While some activists have found success in their efforts to legally defend their territory, others have been targeted—especially Indigenous peoples, who are frequently at the forefront of land disputes and environmental activism.

- 12Naine Terena, “Véxoa: We Know,” in Véxoa: Nós sabemos, 13–14.

- 13For more about the relationship between Indigenous people and ancestral land, see Ailton Krenak, Ideas to Postpone the End of the World, trans. Anthony Doyle (Toronto: Anansi Press, 2020). For more on the intrinsic value of nature, see Eduardo Gudynas, Derechos de la naturaleza: Ética biocéntrica y políticas ambientales (Lima: Programa democracia y transformación global, 2014).

- 14Adriano Pedrosa read Baniwa’s letter in an introduction to “the fourth seminar in a long-term project that anticipates MASP’s 2023 program of exhibitions, lectures, workshops, publications, and courses dedicated to Indigenous Histories,” streamed live on November 9, 2021, YouTube video, 6:04:25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9o4rlMfSadA.