“I have not graduated from Gutai’s way of thinking. I still want to do something new, that which has not existed before.” Motonaga Sadamasa was eighty-six when he made this reflection on Gutai in 2008, thirty-six years after the group had disbanded. Gutai was not a collective bound by rules of art-making. Rather, it was a group of individuals committed to pursuing new possibilities in art and brought together under the leadership of Gutai founder Yoshihara Jiro. Each member pursued his or her own idea of newness. Motonaga spent a lifetime experimenting with material, form, and the possibilities of the brush.

In 1955, one year after the Gutai Art Association was formed, Motonaga became a member. He would participate in all Gutai exhibitions until 1971. In this interview, Motonaga describes his initial encounter with Yoshihara as well as the work he made for his first Gutai exhibition. With little money to invest in materials, he experimented with cheap, non-art mediums and found objects. Living in New York from 1966 to 1967, he developed a technique with acrylic paint and airbrush that foreshadowed his later, hard-edge paintings.

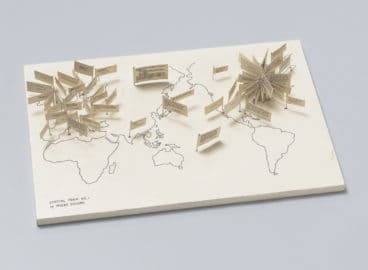

Before he died in 2011, Motonaga planned the reconstruction of his Work (Water) (1956) for the Guggenheim Museum’s rotunda. The piece was realized in 2013. The original, which consisted of transparent polyethylene tubes filled with colored water and stretched between trees in Ashiya Park, was among the earliest works he created for Gutai. Before environmental art and new media art gained currency in 1960s Japan, this work reflected concerns for site-specificity and the crossing of boundaries between painting and sculpture. It embodied the Gutai spirit of innovation that characterized Motonaga’s life’s work.

Interview with Motonaga Sadamasa conducted by Kato Mizuho and Ikegami Hiroko, December 9, 2008, at Motonaga’s studio, Sakasegawa, Takarazuka City. The artist Nakatsuji Etsuko, Motonaga’s wife, also took part. The interview has been lightly edited by post.

Motonaga: [When I came to Kobe], I wanted to see two people: Suda Kokuta and Yoshihara Jiro. When I submitted my work to Ashiya’s city exhibition, I saw Mr. Yoshihara for the first time. When I showed a painting of a nude, which had won a Holbein prize [in 1952], I couldn’t tell his response. However, the next year I submitted an abstraction. I later heard that during the jury process, my work was almost disqualified after some judge decided, “It’s not a painting.” This happened when Yoshihara stepped out to use the bathroom. When he came back to his seat and saw it, he was very complimentary and said, “It’s interesting. Let us give it a prize.” I gained confidence with this. I thought I could paint as many like that one as I wanted.

Kato: You depicted Mount Maya.

Motonaga: Yes, I was inspired by Mount Maya. I didn’t portray a mountain.

Kato: It’s called Takara ga aru (There’s Treasure) [1954].

Motonaga: Yes, that’s the one. I didn’t know how to make an abstract painting. So I was at a loss for quite a while. One evening, looking from Uozaki toward Kobe, I noticed Mount Maya. It looked like an upside-down bowl on which many neon signs were lit up. Perhaps there was an amusement park there back then.

Kato: Yes, there was. At the top of the mountain.

Motonaga: A few years ago, we went there to shoot a TV program. There is nothing there now except houses and buildings. At any rate, I saw the neon lights on top of Mount Maya. I thought, “A mountain of Kobe is very beautiful.” It’s very dark in the mountains of Iga at night. However, I thought, “Mountains of Kobe are very fashionable. I want to incorporate this into my work.” That’s how I made Takara ga aru. I heard that other judges asked Yoshihara, “Is this enough?” And Jiro-san’s [Jiro Yoshihara’s] answer was, “It’s interesting.” He had a different way of seeing it. He wanted to see something new, that which had not existed before. In this sense, since I made that painting knowing nothing about abstraction, it looked very new to him. The judge who thought “it’s not a painting” saw it based on a received idea of how a painting should look. My painting was a mess, with paint not sticking to the surface properly. I had never painted abstraction before. I didn’t know what abstraction was and that’s why it was good. Then, I was suddenly called up and told to show something at Gutai’s first outdoor exhibition held in a pine grove in Ashiya [July 25–August 6, 1955]. But I had no money. I went to the site, wondering what to do. I saw a water faucet there. “Water is free!” I bought some vinyl sheets [and made bags], into which I poured water that I colored with ink. Then I hung the sacks from pine branches. That was my first water work.

Interview with Motonaga Sadamasa conducted by Kato Mizuho and Ikegami Hiroko, December 9, 2008, at Motonaga’s studio, Sakasegawa, Takarazuka City. The artist Nakatsuji Etsuko, Motonaga’s wife, also took part. The interview has been lightly edited by post.

Kato: Were vinyl sheets readily available back then?

Motonaga: Ah, yes, they were sold here and there. They weren’t that big. Ninety centimeters square, or something like that.

Nakatsuji: Haven’t you said previously that you used vinyl furoshiki [traditional wrapping cloths]?

Motonaga: That’s right. I used furoshiki. They were not long at all, because they were cut into ninety-centimeter squares. They cost about ten yen apiece, I think. I got red ink from Mr. Hayano, a poet living in my neighborhood, and tinted the water. Jiro-san came to see it. “Oh, a water sculpture. That’s interesting,” he said. “This is the first-ever water sculpture in the world.” I thought, “Oh, really! If this is good, I can make many of them.” This is how I built my confidence. I was told, “A newspaper reporter will come and see your work.” I couldn’t believe it, but a reporter came from Kobe shinbun. That was my first newspaper interview.

Kato: I think you drove many nails into pieces of wood for that exhibition.

Motonaga: I painted logs and pounded nails into them [Nails, 1955]. Back then, I thought hard to come up with something, “What can be interesting but cost little money?” That was my approach. If I had been rich, I couldn’t have made these works.

Kato: A little before the nail work, you also used a sieve and things that you picked up on the beach.

Motonaga: I showed that work at Ashiya’s city exhibition. I used a sieve before I painted the abstraction. As I lived in Uozaki, I went to the beach to look for something interesting. I found many things, including sieves and corks. I tried to figure out how to make a work out of them. That’s how corks and a sudare partitioner were used in my sculpture. So I walked on the beach of Uozaki and thought up an abstract sculpture for the first time. As for an abstract painting, when I was trying to figure out what to do, I happened to see Mount Maya. Did you know that Ashiya’s city exhibition had a sculpture section, a painting section, a photography section, and a Nihonga [Japanese-style painting] section? I submitted works to all the sections.

Kato: Is that so?

Motonaga: Yes, I submitted my work to all the sections and I got the prize in all the sections.

Kato: How did you come up with your pouring technique, in which you seem to have applied the traditional technique of tarashikomi. [In tarashikomi, diluted black ink or a color wash is first applied. Before it dries completely, either darker sumi (black ink) or color wash is dropped in to create an effect of pooled colors with softly blurred edges.]

Motonaga: I was familiar with work by Hamabe Mankichi, who made something similar to Nihonga. So I knew about tarashikomi from seeing his work.

Kato: In the past you told me that you would prepare a plan, or you would think of forms in advance.

Motonaga: I draw forms first. When I pour paint, I don’t know where it will go. Like I do now, I drew many forms in notebooks. Where to pour paint and such—I also thought of these things as I drew forms.

Kato: How did you decide on the colors? Was it, like, blue over yellow?

Motonaga: No, I just followed my inspiration. One idea after another came to me. I used oil paint, and so if I mixed much oil, the paint became very watery. I poured it [on canvas]. So I discovered that heavier pigments sink more quickly, and that the lighter pigments flow farther.

Ikegami: So different colors have different weights?

Motonaga: Each color has its own weight. Red is rather heavy, for example. By trial and error, I discovered, “Oh, this color is light.”

Ikegami: And the paints flow in layers.

Motonaga: That’s right. They flow like that. And this method made a very complex effect. However, if I watched them flow, I thought, “Oh, this color is flowing that way,” or “Please flow this way.” So I realized I should not watch them flow. So, in the evening, I went out for a drink. When I came home, I had a masterpiece. I had to go out and drink to make this kind of painting. That’s a joke, but this technique involves gravity and time.

Kato: You signed a contract with Martha Jackson Gallery in 1960. Was it through Michel Tapié?

Motonaga: Yes, I think it was at his recommendation.

Kato: What kind of contract was it?

Motonaga: Every month I was supposed to send one large and one small work to Martha. The [signing] fee was seventy thousand yen.

Kato: You mean Japanese yen.

Motonaga: Yes. “Large canvas and small canvas.” That’s it. So, I sent a 150-go and a 100-go [approximately 190 x 130 cm and 230 x 180 cm]. I didn’t send them every month. I sent them in batches. That was my contract. In retrospect, the fee covered just the cost of materials. At that time, I was happy to get seventy thousand yen. However, Gutai wanted to take 30 percent of it. I said, “It’s not as if I’ve sold any work. It’s just a contract fee. It’s not that much.” They didn’t budge. After paying out 30 percent, the remainder was a little more than forty thousand yen. With that I made a 150-go and a 100-go [every month]. The shipping was not included. I sent my work to New York a few times over the course of one year.

Ikegami: So the fee was sent to your bank account?

Motonaga: A bank? I don’t remember.

Nakatsuji: Did they send it to Gutai and you got it from Gutai?

Motonaga: Paid via Gutai? I wonder if it was a bank transfer.

Nakatsuji: I kind of remember having paid something to Gutai. I remember we had to give 30 percent.

Motonaga: Yes, we had to. I don’t remember so well, honestly.

Kato: What did Yoshihara say about it?

Motonaga: No word about it. I don’t think he said anything to me.

Kato: The following year, you signed a contract with Tapié’s International Center of Aesthetic Research in Turin.

Motonaga: My contract with Martha Jackson was for one year. For the next year, Tapié arranged a contract with the center. So I did the same the following year as I had done with Martha in the previous one.

Kato: In 1961 Martha Jackson held a solo exhibition of all the works you sent her.

Motonaga: Yes, this is what I heard.

Kato: What was this exhibition like?

Motonaga: I don’t know. I didn’t go. I wish I had gone. I thought, “They can do whatever they want to do.” So I didn’t go.

Kato: [When you came to] New York, you resumed painting. I heard that you changed your method because the materials were different from what you had used in Japan.

Motonaga: Yes.

Nakatsuji: Martha Jackson introduced him to a large art supply store.

Motonaga: That’s right.

Nakatsuji: She told you, “You can go there and buy anything you want. Any painting material.”

Motonaga: Right. She told me I could buy on the gallery’s credit.

Nakatsuji: At the store we found acrylic paint. There was no Liquitex in Japan at the time. Everybody in New York used it.

Motonaga: The liquid paint I used in Japan was enamel mostly.

Nakatsuji: When you went to the store, you didn’t see enamel?

Motonaga: I could not explain such a difficult thing in English.

Nakatsuji: Anyway, Martha introduced him to the store and he discovered acrylic paint. He bought it because everybody was using it.

Motonaga: Airbrush was also very rare at the time [in Japan].

Nakatsuji: So he found many new things at the store.

Ikegami: Where was the store?

Nakatsuji: Where was it? It was a large store. Martha said that de Kooning bought all his materials there, and so Motonaga should do the same.

Motonaga: De Kooning was also Martha Jackson’s artist. Sam [Francis], too. Sam and de Kooning. And [Karel] Appel, too. These artists were in Martha Jackson’s stable.

Kato: How was the new material?

Motonaga:I usually begin with form. In the previous ten years, I had poured paint, but I thought in New York it would be good to return to form. When I let the paint run, I used gravity. It’s beyond my intention. I wondered what could replace it. Then I found an airbrush. I thought of painting in terms of form by using an airbrush. I thought of what I could do with it. That’s how I felt in New York when I resumed my work.

Nakatsuji: I think it was more like you were groping in the dark.

Motonaga: Well, groping in the dark, you say. Yes, that’s what I felt, as I didn’t know what I was doing.

Kato: You just mentioned that you wanted to explore form. I think your color is very particular, too. How about color? How do you decide on colors? Which comes first, color or form?

Motonaga: Form comes first, of course. Otherwise, I cannot decide on color. I always carry a notebook [to record] interesting forms, so that I can think about them later. As for color, my basic colors are red and green.

Nakatsuji: You seem to use color intuitively.

Motonaga: Yes, it seems I have my own colors.

Nakatsuji: I think you deliberate on form, but you use color instinctively.

Motonaga: Yes, I have my colors. Say, with crayons, everybody has colors they don’t use. These [colored crayons] become leftovers. That’s the person’s character. As a child I could not use the leftover colors, even if I was told to do so. Basically, the colors that get used are my colors. Those are my colors.

Kato: Yes, indeed, orange-tinted red and yellow-green are very characteristic in your work.

Motonaga: My red is vermilion but Shiraga’s red is crimson lake. He loves bloody red. We are very different. I cannot use his red, which is so unpleasant. [Laughs.] But humans are strange. We all have our own different colors.

Kato: Certainly, we do not think color. Color is more about the senses.

Nakatsuji: I agree.

Motonaga: Yes, that’s true with color. Still, I am thinking about it. [Laughs.]

Nakatsuji: You certainly think about it, but you end up with your colors.

Motonaga: Of course, that’s the way it is. Right now, my colors are red, blue, and yellow. But blue is not easy to work with. I use it in some places in a work. A little bit of blue. But I cannot use it too much.

Nakatsuji: You say too much blue makes it feel cold.

Motonaga: Yes. That’s no good. In place of blue I can use purple, but I don’t like dark purple.

Kato: In fact, I see light purple and yellow [in many areas].

Nakatsuji: But in the past you used lemon yellow a lot. Recently, you haven’t used it so often.

Motonaga: It’s my age. I used lemon yellow before, but now I like a bit darker yellow.

Kato: I am interested in your forms, but I think your color is special. I sense your color embodies “this is Motonaga!” That is why I wanted to know how color factors into the process of your production.

Motonaga: First, form. I draw form and think about color. So, form and color are inseparable. I cannot think about them separately. So, if you put a red sheet of cellophane on your eyes, everything in the world looks red but things all have their forms. If you look at a white wall, it looks red. That is a world of color. Like Kelly, he paints a whole canvas in yellow.

Kato: Ellsworth Kelly, you mean.

Motonaga: So he does. But, after all, the canvas is a rectangle. So you cannot say it’s formless.

Ikegami: After you quit Gutai, did your work change?

Motonaga: No, it didn’t change. I don’t think my activities changed so much. I have been very busy. That’s a good thing about me.

Ikegami: Yes, you have continued to make your work.

Motonaga: At that time, I thought, “I have graduated from Gutai Art School.” I had known nothing, but at Gutai, I got hands-on training. I showed in many exhibitions and I became a painter. It’s very strange. So I thought, “I graduated from Gutai Art School.” I told this to [Murakami] Saburo, who said, “I cannot graduate from it.” I thought, “That’s one way to say it.” He was a philosopher: “No matter how far I go, I cannot graduate from it.” That’s one way of thinking about it. In my case, Gutai is gone, so I can say I graduated from Gutai. But I think San-chan [Murakami’s nickname] is right, too. I have not graduated from Gutai’s way of thinking. I still want to do something new, that which has not existed before. My picture books, too, are experimental. I made a picture book with abstraction for children. In that sense, I haven’t graduated from it. Even after graduation, you keep the spirit. I didn’t go to college. So, I want to say I graduated from Gutai Art University.

Transcribed by Kawai Yuki

Translated by Reiko Tomii

Oral History Archives of Japanese Art (www.oralarthistory.org)

The Japanese version of the interview can be found on the website of the Oral History Archives of Japanese Art. In accordance with Japanese practice, Japanese names are generally written surname first. Exceptions are made for Japanese-born individuals who reside permanently abroad, or are well-known in the West.