Initiated in the late 1950s in Zagreb, in the former Yugoslavia, and dissolved less than a decade later, the Gorgona Group continues to fascinate. Since the group’s first exhibition in 1977, generations of artists and art historians from Eastern Europe have viewed its ephemeral, collective artistic practices as the foundation for the later development of Conceptualism, which flourished in late 1960s Yugoslavia as much as it did anywhere else in the world.

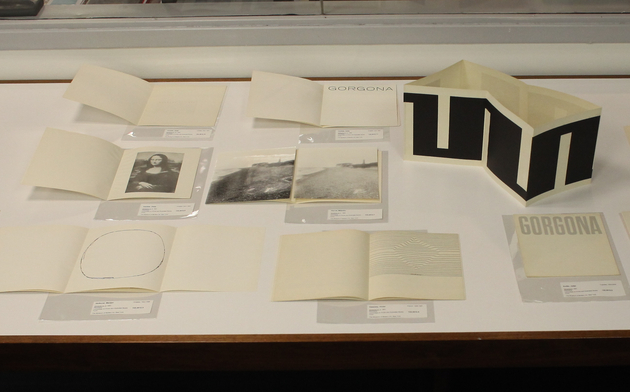

While the most comprehensive collection of works by Gorgona artists is held by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, extensive research by MoMA curators has led to the acquisition of a significant number of pieces for the Museum’s collection. These include a complete set of the magazine Gorgona as well as numerous important works by Dimitrije Basicević Mangelos and Josip Vaništa. After C-MAP trips to Zagreb and Belgrade, we invited the art historian Jesa Denegri, an expert on the group and a personal friend of many of its members, to join us for an intensive seminar at MoMA. Together we viewed the Museum’s Gorgona holdings and engaged in conversations about the group’s lasting importance.

Below you will find the transcription of Denegri’s presentation to the C-MAP Fluxus Group at MoMA in December 2012, together with the discussion that followed. Denegri describes the difficult-to-define character of Gorgona activities, discusses the group’s involvement with both the Yugoslav and international art scenes, highlights the changing reception of the group’s work, and points to the difficulties of producing a concise narrative about its history.

Magdalena Moskalewicz

What is (was) Gorgona Group?

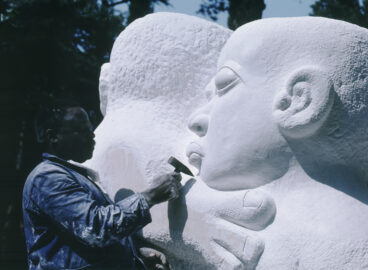

In this talk I wish to give a brief presentation on the phenomenon known as Gorgona Group and to situate it in the context of its time in the former Yugoslavia. Gorgona Group was an artists’ collective that existed in Zagreb, Croatia, between 1959 and 1966. Its core members were the painters Josip Vaništa (1924), Julije Knifer (1924–2000), Marijan Jevšovar (1922–1998), and Đuro Seder (1927); the sculptor Ivan Kožarić (1921); architect Miljenko Horvat (1935–2012), who also worked as a painter and photographer; and the art historians and critics Radoslav Putar (1929–1994), Matko Meštrović (1933), and Dimitrije Bašičević (1921–1987), who was later active in the group as an artist and used the pseudonym Mangelos. Several informal members and friends were also involved in the group’s activities.

Gorgona Group took its name from a verse in a poem by Dimitrije Bašičević that was published as a preface to the graphics portfolio Elualija. It refers to the eponymous monster from Greek mythology that petrified with a single look anyone who came face to face with it. Although the name was chosen randomly, it later became evident that it fit very well with the fundamental mentality of this small community of artists and intellectuals brought together under the specific historical and social circumstances that prevailed during its brief existence.

Gorgona Group’s beginnings and first public appearances

Avant-garde movements and postwar, neo-avant-garde artists’ groups usually formed around commonly proclaimed or implied principles, but this was not the case with Gorgona Group. The group’s exact founding date is unknown, and as Nena Dimitrijević, the first historian to study the group, has indicated, Gorgona wasn’t exactly active—it just existed. The above-mentioned artists and art critics met occasionally, but rarely all together. They socialized and went for walks in the center or outside of town without any defined plans or conclusions . They talked spontaneously about seemingly insignificant topics from their day-to-day lives and exchanged opinions about books they had read, but they never discussed their artistic preoccupations and professional activities, since these remained the sovereign right of each individual. They also exchanged written notes, called “thoughts for the month,” which were sent by post even though they could have been exchanged in person far more quickly and easily. Josip Vaništa was the originator of these gatherings of a few friends. They would meet in his apartment or his office at the Faculty of Architecture in Zagreb, where he worked as an assistant lecturer in drawing.

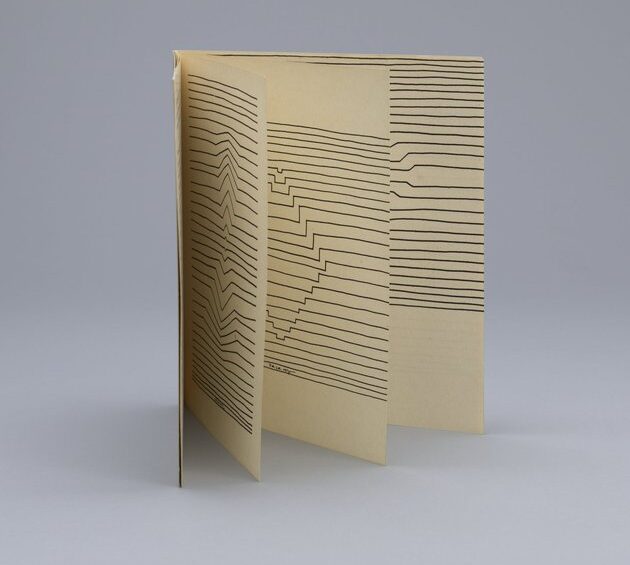

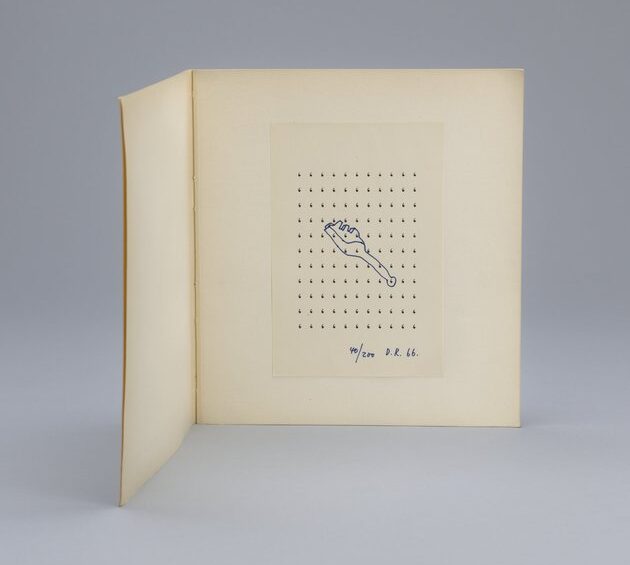

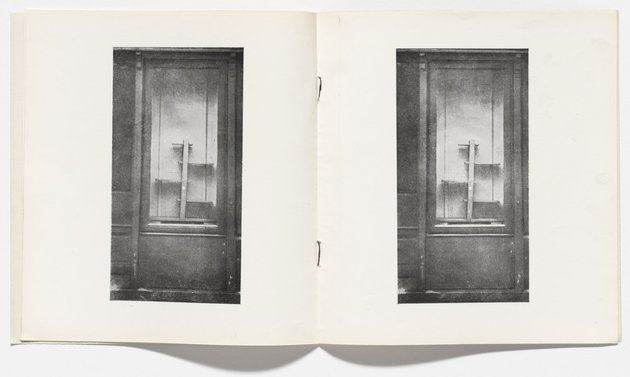

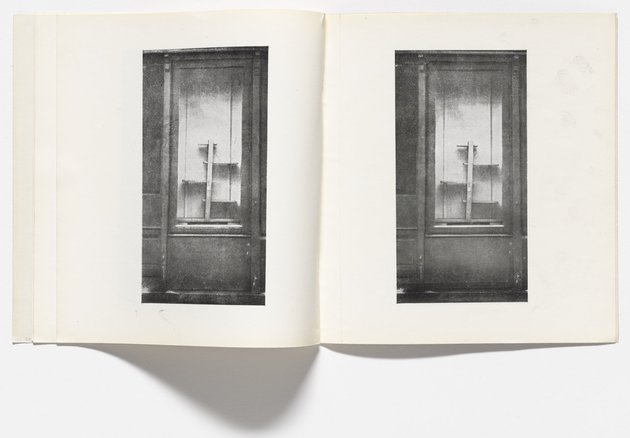

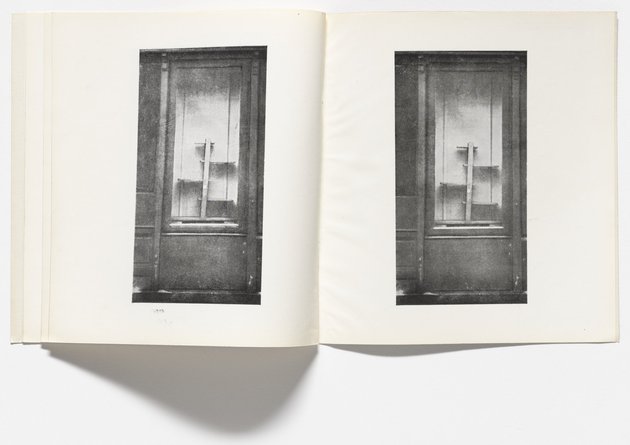

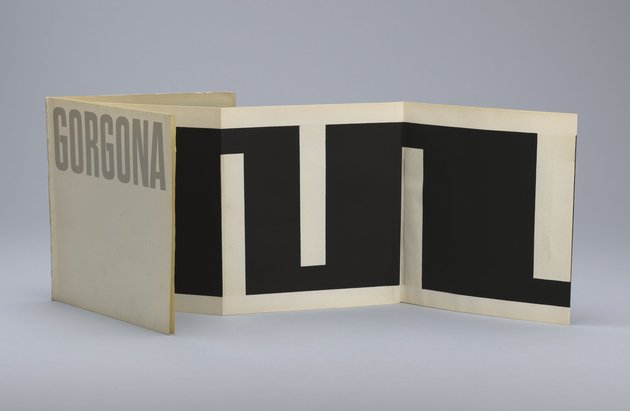

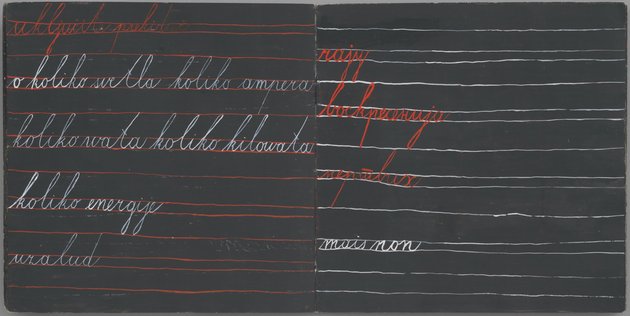

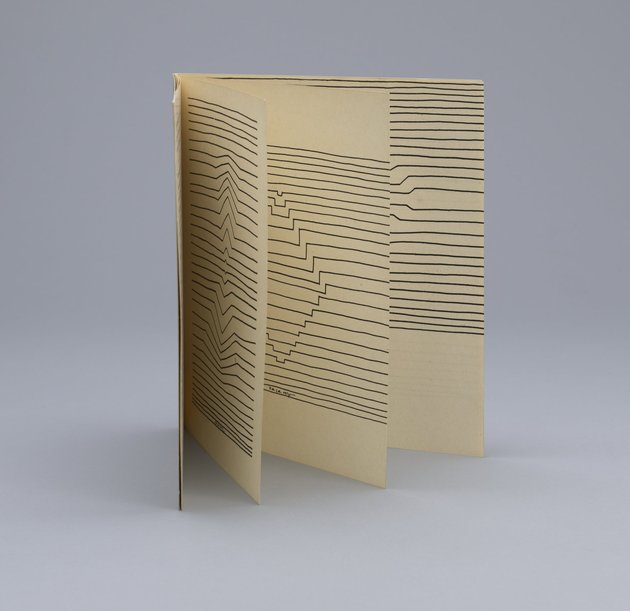

Gorgona’s existence became known within Zagreb’s artistic milieu sometime in the early spring of 1961, when a magazine bearing the group’s name was distributed free of charge, literally from hand to hand, without previous notice. The first issue was the work of Vaništa, and an issue by Knifer followed soon afterwards. The publication was later defined as an “anti-magazine” to underline its difference from conventional types of literary and art journals. Still later, the individual issues would be called artist’s books or “books as artworks.” In his recollections of the beginnings of what was even for him an unforeseeable adventure, Vaništa describes anecdotally how this seemingly absurd undertaking came about. In time, its far-reaching historical and artistic significance would become evident:

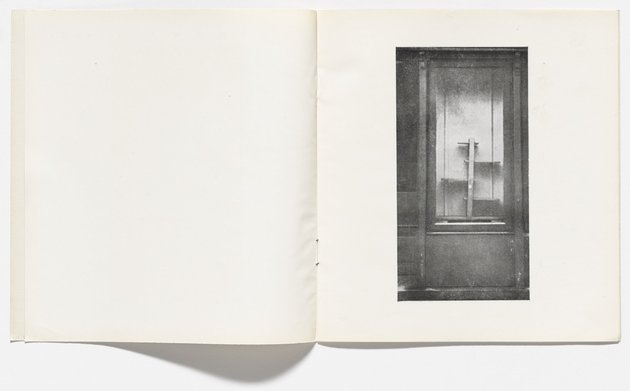

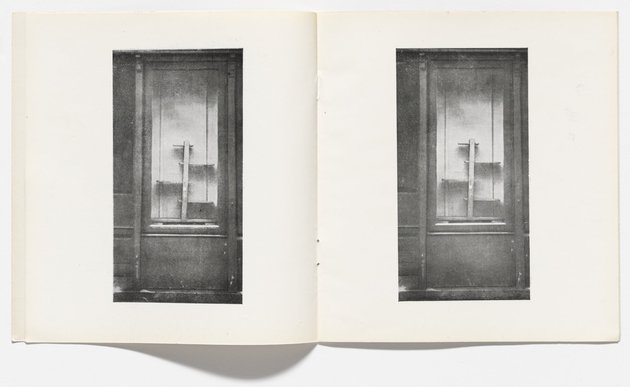

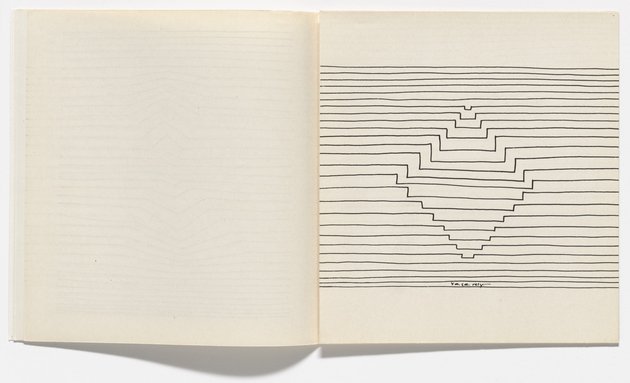

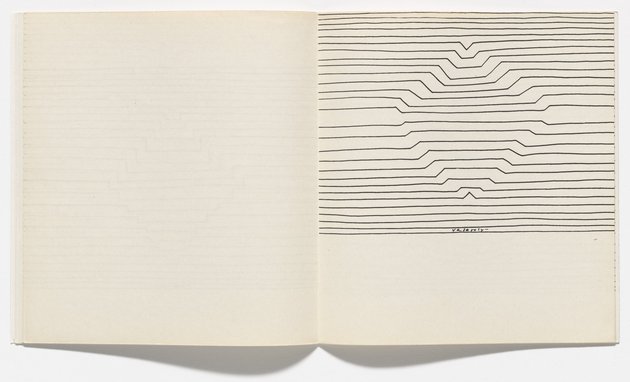

“In the winter of 1960, while passing by a second-hand store in Vlaška Street right across from the Studio movie theater, I spotted an unknown object in the shop window: a vertical plank connecting four horizontal planks. It was a spatial structure without purpose being offered for sale. Perpendicular winter lighting fell on the display, and the object cast a shadow on the light background wall. I stood fascinated, probably because of the closeness between the scene before me and the still-life from the ’50s in which I had divided interior from exterior by placing a vertical line in the middle. I asked my friend Pavel Cazjek for a favor, and the next morning we photographed this shop window. I decided to repeat the photo nine times. I made a model, had it printed, and the first issue of Gorgona appeared during Easter week of 1961 (as did issue 2, a meander by Julije Knifer). This was the beginning of Gorgona . . . The first two issues seemed to link the group more closely together. Ideas were born but few of them were materialized, realized. The environment was in consternation, but sympathetic individuals began to emerge within the country and abroad.”

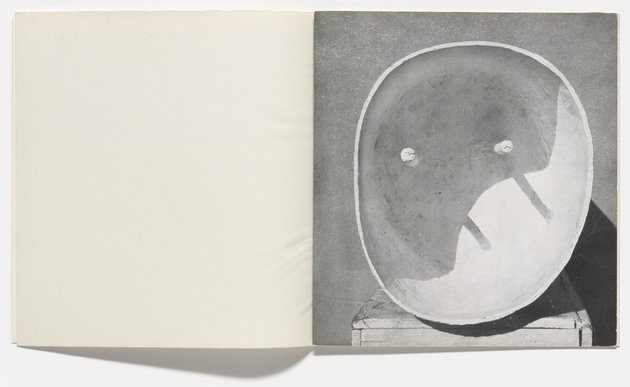

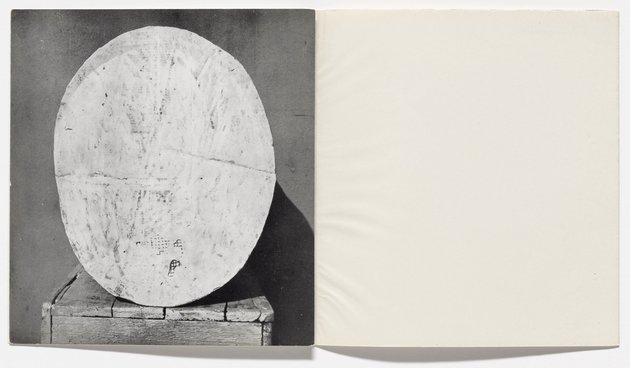

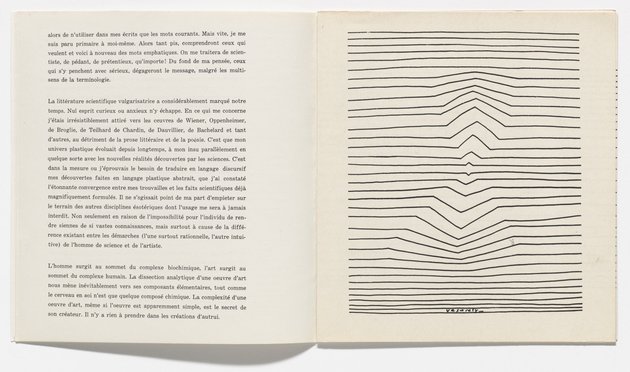

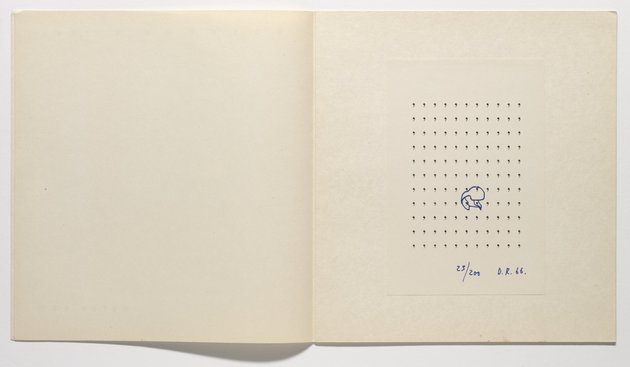

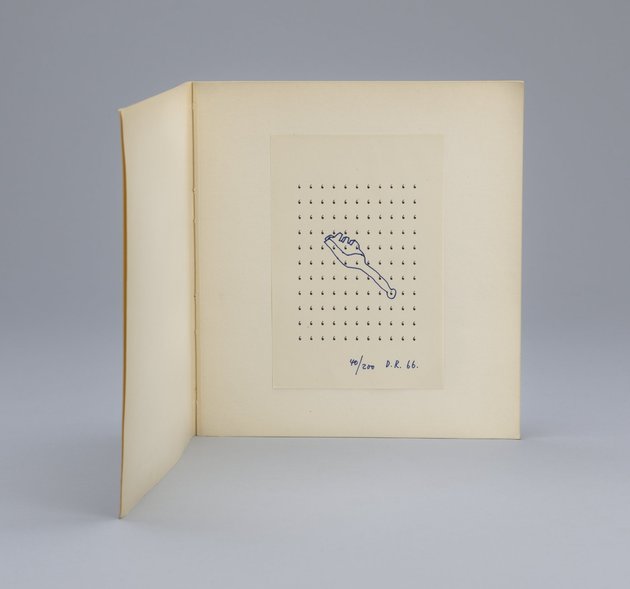

More issues of the anti-magazine Gorgona followed. In 1961, they were created, respectively, by Jevšovar, Victor Vasarely, Kožarić, and again Vaništa. Then came a break until 1965, when issues by Horvat and Harold Pinter came out. Nineteen sixty-six saw the publication of one number by Dieter Roth and two—the last in the Gorgona series—by Vaništa: a total of eleven issues. Some ideas and projects were left unrealized, as can be seen in the correspondence with potential authors such as Lucio Fontana, Robert Rauschenberg, Piero Manzoni, and Enzo Mari. In Vaništa’s Gorgona archive, two Manzoni proposals titled “Tavole di accertamento” are kept as particularly valuable and now have the status of some sort of manually created unicum; they were to have been printed editions of a multiplied art object.

A series of group and solo exhibitions of works by members and their guests was organized by Gorgona between 1961 and 1963. Foreign artists François Morellet and Piero Dorazio, both of whom participated in the first exhibition of the international New Tendencies movement in Zagreb in 1961, were included. Their solo shows were privately organized in Studio G, a small frame shop in the very center of town that was rented for an insignificant fee. The organizers’ aim was to realize their exhibition program independently of the influence and control that were being imposed upon state-run social and cultural institutions . The exhibitions at Studio G could be distinguished from other exhibitions in town on first glance. Only one work (such as Knifer’s famous Meander in the Corner, 1962) or merely a few were shown, contrary to the customary overcrowded displays in most other solo or group exhibitions. All visible manifestations of Gorgona Group (the eponymous anti-magazine and exhibitions organized by the group) thus stood out from their surroundings. They were, in a word, detached from the prevailing spiritual climate of their environment. From this we can deduce that “Gorgona behavior” was a fully conscious and far-reaching strategy of silent contestation. Seemingly passive on the outside, such behavior was essentially a persistent and defiant form of resistance on behalf of not only artistic but also total individual freedom.

Characteristics of paintings and sculptures by Gorgona Group members

One of the paradoxes of Gorgona Group, which was made up of prominent Croatian artists of two generations (young and middle-aged) and a trio of influential art critics, is that it was almost completely unknown on the cultural scene in which it was embedded. This situation continued until the group’s first historical reevaluation in a retrospective at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 1977. Thus, the question arises: what is Gorgona Group’s legacy? Is it limited to the eponymous anti-magazine, to exhibitions and other manifestations of “Gorgona behavior,” or does it include the members’ artistic productions? In other words, are the paintings and sculptures of Gorgona Group members an integral part of the group’s overall legacy, or are they the personal expressions of its individual members? We are inclined to accept the first proposition. All of the work created by members of Gorgona Group during the group’s existence, including individual bodies of painting and sculpture, is part of the group’s legitimate legacy. All Gorgona Group artists created works with distinctly non-iconic characteristics. Jevšovar, Seder, and Horvat painted in the spirit of radical Informel; Knifer’s painted black-and-whites meander, with their barely perceptible variations, and Vaništa’s horizontal lines in the midst of two-dimensional backgrounds suggest unique strains of Minimalism; Kožarić’s sculptures and Mangelos’s objects conform to no classical definition of sculpture, establishing parameters valid only for themselves. All of these artists worked entirely outside the prevailing aesthetic of moderate modernism that was then dominant in the local production of painting and sculpture. They veered from it even more significantly in their profound mentality than in the external characteristics of their formal language—as if to create a direct reflection of their ideological positions.

Gorgona Group’s modalities of dematerialized art

If it is possible to debate whether the painting and sculpture production of individual Gorgona Group members rightfully belongs to Gorgona Group’s overall legacy, it is indisputable that Gorgona Group’s collective art practice encompassed activities that did not result in tangible, material art objects. These activities included collective gatherings (such as the “collective reviews” at the beginning of spring or in the fall); performances (such as Adorations at the opening of Julije Knifer’s exhibition in 1966); communication via post between group members (such as the “thoughts” for certain months of the year); intellectual games without rules or final outcomes; photographs of various situations; newspaper ads with real or fictive notices; the mailing of notes in which no sense or purpose can be discerned (such as an invitation that says “Please attend” but gives neither time nor place); records of “collective works” by Gorgona Group members that could not and were not meant to be carried out in reality; “impossible projects” proposed mostly by Kožarić; records of Gorgona Group meetings written by Putar in an ancient, obsolete language and with an ironic subtext, etc. No one outside the group understood any of this as art at the time that it was being carried out. That recognition came only much later, and was largely thanks to the promulgation of the theories of the dematerialization of art and art in an expanded field. The term “art” itself has become so conditional and flexible that it is definitively being invalidated today, and all strict boundaries between what art undoubtedly is or could potentially be are lost.

Gorgona Group within national and international contexts

Gorgona Group’s national context comprised the social, political, and cultural circumstances in Yugoslavia midway through the twentieth century. In the visual arts, the complex process of adopting the enforced, repressive style of Socialist Realism—after the Soviet model—took place under the strained circumstances of the Cold War. Then, in 1948, due to the political break between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union caused by a Cominform resolution, came the gradual transition to a more tolerant cultural and artistic climate, which resulted in a steady opening up to the West. This significantly benefited the appearance and affirmation of different vocabularies in postwar modernism.

The far-reaching transformation of the artistic situation was prompted by the strategy of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy to balance on the border between East and West, with an increasingly apparent inclination towards the West. One of the results of this transformation was the establishment of an institutionalized art system in which, sometime during the mid-1950s, the new mainstream would take the form of what in recent literature has been dubbed “socialist modernism.” A series of spectacular foreign art exhibitions held in major cities of the former Yugoslavia served as significant levers for the functioning of the “socialist modernist” art system. They included Contemporary French Art in 1952, a solo exhibition by Henry Moore in 1955, Contemporary American Art from the collection of the Modern Museum of Art in New York in 1956, and numerous others. At the same time, Yugoslavia was regularly represented in international events such as the contemporary art biennials in Venice, São Paolo, and Tokyo, to mention only the most important. On the occasion of the exhibition Contemporary Yugoslav Art in Paris in 1961, French critic Michel Ragon wrote the following praise, pinpointing the difference between Yugoslav art and art in countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain: “In Yugoslavia, living art is also official art.” Striving to strengthen not only political and economic but also cultural relations with the West, the regime of Socialist Yugoslavia added to its strategic plans and objectives the principle of freer development and material support for contemporary modernist art. The controversial question remains as to which artistic expressions and their creators were favored by and sought to benefit from these changes and privileges. Individually and collectively, Gorgona Group members did not, nor did they strive to. The characteristics of so-called “socialist aestheticism”—the soft” or “middle” line of contemporary art in Yugoslavia in the initial postwar decades—cannot be found in their art. Nena Dimitrijević has presented a convincing account of the aims of Gorgona Group and its detached position within Yugoslavia’s art space:

“Gorgona was in the process of seeking spiritual and intellectual freedom, the realization of which was an end in itself. Outside the professional responsibilities of artistic production and promoting itself and its colleagues in the hierarchy of the local art scene, this group was motivated to gather and communicate solely by the prospects of spiritual unity and kinship. Regardless of the differences between their individual creative concepts, group members were unified by their shared embrace of the spirit of modernism, which is defined by the recognition of absurdities, emptiness, and monotony as aesthetic categories, and a tendency towards nihilism and metaphysical irony. From a contemporary standpoint it might seem that these spiritual coordinates insufficiently specify the sphere of action of an art group, but at the time of Gorgona Group’s emergence, Yugoslav art was dominated by completely opposite values and critera, and the group’s vital energy smoldered as it opposed the artistic establishment of that time.”

Gorgona Group’s international context was the global art situation in the early 1960s, with phenomena such as American Neo-Dada, Minimalism, Fluxus, Paris New Realism led by Yves Klein, the German group Zero, and Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani’s magazine/gallery Azimuth/Azimuth in Milan. The artistic practices of individual Gorgona Group members, developed at approximately the same time, exhibited certain similarities with those of their colleagues abroad. Parallels in time are noticeable between Gorgona Group and the Situationist International, which published twelve issues of their eponymous magazine between 1958 and 1969. Both of these groups strove in extremely different manners for the emancipation of the individual. This was also the time of the revival of Marcel Duchamp and his concepts of the readymade, the priority of artistic intention, and the recognition that art is primarily mental rather than optical and retinal. Certain Gorgona Group members were familiar with all of these contemporaneous developments, learning about them through specialist journals, firsthand experience, and by word of mouth. They yearned and strove to establish connections with their spiritual kin abroad. Vaništa invited Fontana, Manzoni, and Rauschenberg to contribute to their anti-magazine, Gorgona, and sent newly published issues to numerous addresses around the world. Contemporary literature read in translation or, less frequently, in the original, played a special part in the intellectual formation and spiritual development of most of Gorgona Group’s members.They were well-versed in the existentialist works of Sartre and Camus and in the French nouveau roman, and they particularly appreciated ancient far-eastern philosophy. They followed the Theater of the Absurd of Beckett and Ionesco, knew about the music of John Cage, attended screenings of avant-garde films, and visited experimental film festivals. It can be concluded that the advanced culture of the contemporary era was the spiritual nourishment of Gorgona Group’s members. Accordingly, artists affiliated with the group considered themselves full citizens of the world, on an equal footing with their counterparts in other cultures.

Relationship Gorgona Group – New Tendencies

Three members of Gorgona Group—Putar and Meštrović as organizers and Knifer as an exhibitor—were involved the first exhibition of the international New Tendencies movement, held at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 1961. This fact inevitably elicits the following question: why did they participate in this exhibition, and what exactly was their share in the subject matter of this exhibition? When considering this question, it is important to bear in mind that three artists from the German group Zero—Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, and Günther Uecker—and two artists from Milan’s Azimuth—Manzoni and Castellani—were among the show’s prominent participants. This information leads us to conclude that in terms of characteristics of expression, the first New Tendencies exhibition in Zagreb was closer to the spiritual mentality of Gorgona Group than to the Neo-Constructivist orientation of technological enthusiasm that would dominate subsequent Zagreb exhibitions, from the second edition in 1963 to the fourth in 1968–69, at which the use of computers in artistic research was introduced. In a letter to Meštrović of June 10, 1961, Manzoni expressed concern that the spiritual kin and followers of Max Bill and Bruno Munari, exponents of the strict geometry of so-called Concrete art linking art and industrial design, could leave an undesirable ideological mark on the exhibition. Manzoni’s fears did not materialize. Within the complex history and ideological turmoil of the New Tendencies movement, Manzoni’s first exhibition could be labeled a Gorgona exhibition if only for its share of Gorgona participants, among other things. Only at the following New Tendencies exhibitions did the issue of the relation between art, science, and new technologies prevail, as the demand for the “scientification of art” was for the most part accepted, except, of course, by Gorgona Group.

Gorgona Group’s historical reevaluation and international affirmation

How did an artistic phenomenon barely known in its own surroundings not only achieve historical r-evaluation on the local art scene but also significant international affirmation? It began with a retrospective at the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 1977 and a text by Nena Dimitrijević in the accompanying catalogue, and continued with the group members’ appearances at the Museum of Modern Art in Mönchengladbach that same year. They were included in the São Paolo Biennale in 1981, in a retrospective in Dijon in 1989, and, under the name Gorgona Gorgonesco Gorgonico, within the framework of the 47th Venice Biennale in 1997. Work by the Gorgona Group was acquired for the Arteast collection of the Modern Gallery in Ljubljana in 2001, and the group is the subject of a monograph by Marija Gattin that was published by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 2002. The most important indices of Gorgona Group’s international affirmation are its inclusion in the exhibitions Aspects/Positions. 50 Years of Art in Central Europe 1949–1999 at the Museum of Modern Art Ludwig Foundation Vienna in 2000; in Eye on Europe: Prints, Books & Multiples, 1960 to Now at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2006; and in Promises of the Past: A Discontinuous History of Art in Former Eastern Europe at the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 2010. Finally, the group is mentioned in Vitek Havranek’s text “Yves Klein et l’Europe de L’Est, un oeuvre à l’état d’idée 1959–1971” in the catalogue for the Yves Klein retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2007.

Individual performances by certain Gorgona Group members, both during the artists’ lifetimes and posthumously, within the country and abroad, should be mentioned as well. It should be emphasized in particular that Gorgona Group first received meaningful recognition during the ascendancy of Conceptual art, and that this initial recognition was accorded by artists and critics familiar with that new art form. The historical reevaluation and international affirmation of Gorgona Group presents an illuminating example of the way in which a change in artistic paradigm can enable an obscure recent phenomenon to achieve proper understanding and precise placement in the context of its own surroundings, as well as on a global scale.

Josip Vaništa’s notes on Gorgona Group

Josip Vaništa’s notes on Gorgona Group from 1961 include the following:

“Gorgona Group’s idea is serious and brief. Gorgona Group does not seek works or results in art, it defines itself as a collection of potential interpretation.

“In 1961, Gorgona Group was fleeing from then-powerful Communism to the irrational, incomprehensible. Gorgona Group’s inaction was noticeable. A few young people whose mutual affection was the decisive factor for connecting met occasionally. Gorgona Group did not have a message! It was a particular type of action, self-ironic, it gave off a feeling of strangeness. Maybe it brought something new, maybe it only resolved its problems in life, anxious feelings. Maybe it did not leave behind anything but friendship and spiritual kinship.”

“Gorgona Group’s aspirations were oriented towards a reality outside aesthetics. Reflective restraint, passivity and indifference were above the naked, ironic denial or the world we lived in. No importance was attached to work, activities were very simple: going for walks together outside town, for example, ‘commission inspection of the beginning of spring,’ as Putar used to say jokingly, ordinary conversations in nature. Sometimes, Gorgon Group did not do anything, it was only living. Like the others, I was interested in the emptiness of Zen at that time, I sought normal behavior, normal life in an ideologically imbued world.”

“Gorgona Group was mere participation in an existence into which it brought a few dark ingredients: absurdity, emptiness. Gorgona Group was not a group of painters. It manifested itself through conversation, ideas, some realizations, with the help of the written word when nothing else could be done.”

Gorgona Group had no theory or poetics, and least of all an ideology. Vaništa’s cited notes are merely an indication by the group’s ideological and organizational leader of his own understanding of Gorgona Group or what it might be. The other Gorgona Group members did not leave even this much about it. However, when an attempt is made to gather and collect all the threads about and related to Gorgona Group, a notion of this highly unusual artistic and above all existential formation nevertheless starts to appear.

What then, after all, is (was) Gorgona Group?

An understanding of the phenomenon that was Gorgona Group did not come about suddenly. It emerged gradually over time, filled in by testimony and assessments of all those who left their opinions, memories, and interpretations—its initiator, a few of the other members and the art historians who took an interest. But it’s as if some elusive and not fully noticeable aura still hovers above this enigma. Gorgona Group was certainly not an art group in any declarative sense. Rather, it was a spiritual and intellectual community that formed in a certain period of its members’ lives. They were artists and art historians close to each other, linked by a shared worldview that arose from the social and spiritual conditions in the time and place of their existence. Within their cramped living conditions, a few young people recognized each other, became close, gathered, socialized, drifted away, and finally, by force of the law of existence, parted. What remained were material traces and intellectual currents that are worth decoding and qualifying using the instruments of art history. When art history will have to account for postwar avant-garde movements in Croatia’s art scene, it will recognize them in two successive waves: in the group EXAT 51 at the beginning, and in Gorgona Group at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s. EXAT 51 was a typical neo-avant-garde phenomenon. It came out with a manifesto, in which it revealed its program advocating the legitimacy of abstraction within the socio-political context of Socialist Realism, then the ruling ideology that was averse to this art. EXAT 51 thus drew polemical reactions of acceptance and rejection. It proposed a synthesis of art, architecture, and industrial design in the wake of the achievements of the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism. It was a characteristic upshot of the enthusiastic and optimistic spiritual climate of the “reconstruction and development” of the social society shortly after the terrible devastation of World War II. Having emerged towards the end of the same decade in significantly different spiritual circumstances, Gorgona Group was the opposite of EXAT in many ways. It did not advocate any collectivist ideals or goals; moreover, it was distrustful of mobilizing utilitarian projects. Rather than aspiring to integrate art and the artist into society, Gorgona members felt that the only thing left to the artist was a belief in art’s absolute autonomy.

Gorgona Group did not accept, but neither did it oppose the standards of the social order in which it emerged. It treated that order fatalistically. It wanted to stand beyond and outside all ruling ideological postulates, finding refuge only in the art created by its members, which they believed in. “Maybe Marijan Jevšovar,” notes Vaništa in his notes on Gorgona Group, “was the closest to the truth when he said that Gorgona Group members behaved as if they were not living under Communism.” Gorgona Group members were not rebels, and they were certainly not political dissidents. They were proud loners gathered in a small intellectual community that privileged a mindset that could tentatively be called “active escapism.” The means of expression of such a mentality were, among other things, irony, measured humor, distanced, casual, mutual respect, with reciprocal giving and taking, refined behavior in relations within and outside the group. If all of these different characteristics were reduced to one, we could say that Gorgona artists were skeptics, people who were not carried away by activism but who were nevertheless quite persistent and consistent in their fundamental beliefs. Gorgona artists were actually loners, but loners who wanted to share their loneliness with others similar and close to them. Their ideal was, above all, the freedom of art. All Gorgona Group members believed in this ideal and were utterly devoted to it, each in his and her own way. Apart from free existence in art, Gorgona artists did not expect or seek anything. Theirs was an art without confession, an art that doesn’t preach but simply exists and survives as an inseparable part of human existence. Thanks to this art, they have been recognized both locally and internationally, and information about them that was once scattered has been gathered into a whole. Today, Gorgona Group is a unique, historically affirmed artistic fact.

Discussion

Christian Rattemeyer: Given the argument that you have laid out about the relationship between Gorgona as a group and the work of its individual members, and given the paradox between the sort of immaterialization of the gesture and the works that remain by individual artists, how would you represent Gorgona in the best possible way?

Jesa Denegri: This is a crucial point in understanding Gorgona. There is a belief that what makes Gorgona are the eleven anti-magazines and all the conversations, walks, thoughts of the day—everything that was mentioned in the text, everything the members were doing, all their different actions. And this is one way of looking at things, one way of defining it. This could be Gorgona. On the other hand, each of the members of Gorgona, each individual, had his own activity, artistic production, and artistic practice as a painter or sculptor. And these practices were very artistic. For example, Julije Knifer was a painter, Ivan Kožarić was a sculptor, and many other Gorgona members were writers. I would say that all this forms different parts of Gorgona: both the artists’ individual practices and their activities as a group. Because ultimately, all the activities of Gorgona, including the works that the artists were producing, were very distinct. They were completely different from the other artistic practices in Yugoslavia at the time, and they influenced the country’s artistic production.

We could say that some of the paintings of the Gorgona members, for example Jevšovar, could be part of the Informel movement. However, if you come closer, if you observe more carefully, you notice there is actually a big difference. I will describe one of Jevšovar’s paintings just to give you an example. It’s a gray surface half a meter [20 inches] in length. And the title is: Gray surface 1960–1962. You could ask: was it necessary to cover the surface with gray paint over a period of two years when it could have been done in twenty minutes? But actually, what this is about is that the color was applied to the surface and then removed, applied and removed. So there is a repetition of the gesture of application and removal. Thus, more conceptual, theoretical questions arose: When was the painting done? When was it over? When is the moment when the artist decides that the work, in this case the painting, is finished, and when is he ready to show it to the gallery, to the collector, to the museum? Behind this very simple gesture lie very complex and multilayered thinking and reflection about the painter’s gesture and the painting itself.

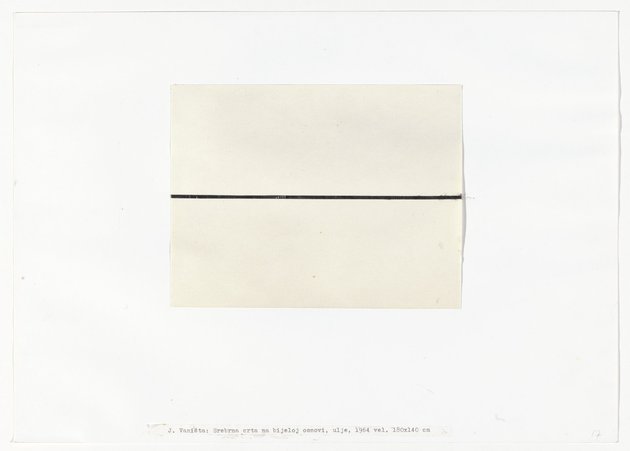

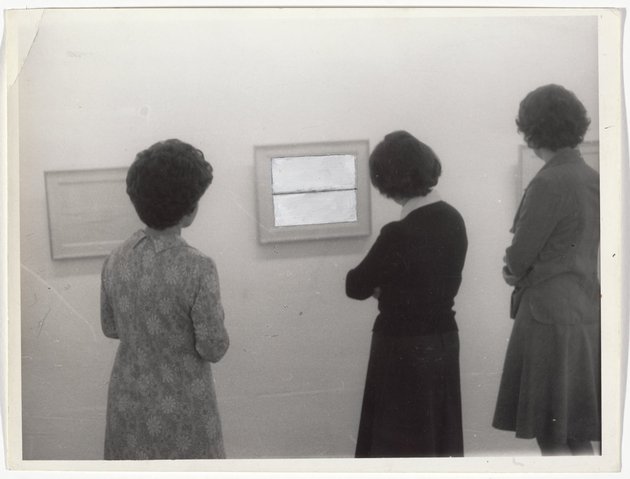

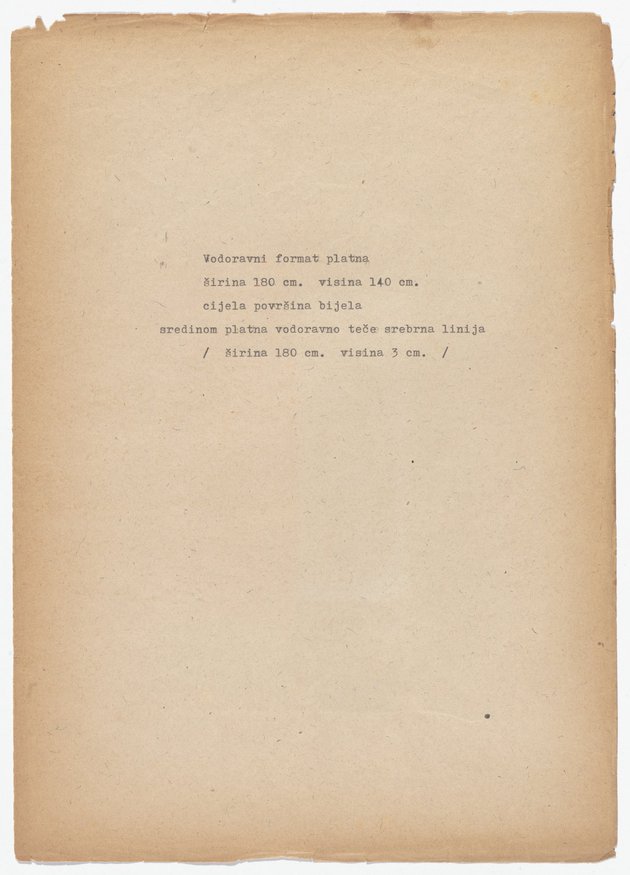

Another important and interesting example is Vaništa’s painting with the silver line in the middle. There is a specific formula, we could say, for this painting. The formula says the painting is 140 high by 180 centimeters wide [approximately 55 by 71 inches], and there is a silver line 3 centimeters [1 inch] thick running through it. This textual instruction was created before the painting was executed.

I could give you plenty of similar examples, particularly related to Julije Knifer, who is one of the biggest painters, not only in the Gorgona group. There are special, more mental and optical-visual characteristics to Knifer’s paintings. In a way, this could be a conclusion, an answer and conclusion to your question: Jevšovar could not be understood in the context of Informel. Knifer cannot really be shown with the Minimalists, although it is possible. But all this production—it is Gorgona. Because it is deeply different from the artistic production and art activities of the other artists of the time, and it has fewer mental and auto-referential characteristics.

If one should make an ideal retrospective of Gorgona . . . When this monograph that I am preparing will be ready, all these objects will be represented: the magazines, manifestos, also paintings, sculptures, and in the case of Mangelos, also his globes. Mangelos is one of the most interesting phenomena not only within Gorgona but in contemporary art in general. When Gorgona was active, he was one of the most prominent art critics and curators. He was the curator of the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, and he was working in the group anonymously.

Christian Rattemeyer: I was wondering what you make of the difficulty posed by the amount of time that sometimes intervenes between the execution of a work and its presentation—for instance, Vaništa’s tendency to remake a work ten, fifteen, or twenty years later, and still give it the original date.

Jesa Denegri: The idea for a work could have originated during the Gorgona time, and the work might have been executed many years later, numerous times. This is why there are sometimes doubts about dating Gorgona’s activities and also some works by the members of Gorgona. For example, Mangelos and his black surfaces with little red crosses: they were made as early as in the 1940s, so if we place them in their artistic or art historical context, they could be placed next to the black paintings of Rodchenko or Reinhardt. But is not a question of creating a black surface. During the war, in the 1940s, these works were for Mangelos a very intimate confession, in a way. It was a confession about the victims of the war, his closest friends, who lost their lives. This production, or that production of that time, doesn’t have the characteristics of something that is supposed to be shown or exposed or exhibited. This came up during the discussion about who did the first black surface, or who did it second or in which context. So for each of the members of Gorgona we could tell different stories that testify to the primacy of the mental and the conceptual over the formal. That’s why I think that everything that was ever done by the members of Gorgona is today a part of Gorgona’s legacy.

Christophe Cherix: Is this not a different situation in the case of Vaništa? We saw some of Vaništa’s sketchbooks from the late 1940s when he was is Vienna, and what’s troubling is that you have the same line drawings, the exact same composition that he would make later as a member of the Gorgona group. Thus, it seems that the form came first.

Jesa Denegri: There is this origin of the horizontal in his drawings. So what you are saying is true, but at a particular moment there came a mental shift when he no longer perceived this line as the horizon line. There is an instruction that determines the structure of the drawing itself, so it is not the horizon line but the instruction that precedes it that is most important. And that is the tautology of the Gorgona, because . . . it is not the horizon line, but it is a line, just a line, just a silver-gray line.

Ana Janevski: If you are saying that today we should consider that every work of the individual members together form the legacy of Gorgona, what about the group’s 1977 exhibition?

Jesa Denegri: It is a very good question. Gorgona was officially historicized in 1977. It was Nena Dimitrijević, an art historian and the wife of Braco Dimitrijević, who wrote a text about the group for the 1977 exhibition in the city gallery in Zagreb. So Gorgona as we see it today, as we perceive it today, actually is the result of the art history, art historical work, but the important and necessary background was the Conceptual art at the end of the 1960s and also in the ’70s. Without this frame or the Conceptual, dematerialized art of the 1970s, without the art critics and curators like Nena Dimitrijević, Biljana Tomić, and others, we would never have had the perception or interpretation of Gorgona that we have today. And it is a very interesting issue from the point of view of art history and the historicization of art movements and art practices. It was necessary to have different shifts and different events in the art, in art history. Certain theoretical and methodological tools needed to be developed in order to read and to interpret Gorgona and the Gorgona phenomena.

The discussion was simultaneously translated between Croatian and English by Ana Janevski.

Tekst na hrvatskom možete pročitati ovdje.