Karlo Kacharava (1964–1994), a prominent Georgian artist, writer, art critic, and poet, has been referred to as “the voice of his generation”1William Dunbar, “The Georgian artist who was the voice of his generation,” Apollo, April 30, 2024, https://apollo-magazine.com/karlo-kacharava-georgia-avant-garde-artist-recognition/. and a “supernova.”2Vija Skangale, “Karlo Kacharava: The Salient Truth of the ‘Supernova,” in Karlo Kacharava: Sentimental Traveller, ed. Irena Popiashvili, exh. cat. (S.M.A.K, 2024) In my contribution to the book Karlo Kacharava: Sentimental Traveller, published in 2023 on the occasion of Kacharava’s solo exhibition in Ghent at S.M.A.K., I discuss the intertwining of his “oceanic” body of work, both visual and written, with his short but extraordinary life.3Skangale, “Karlo Kacharava,” 41. However, in the present essay, I have chosen to focus on his Erased Portraits of Politicians (c. 1988), which are lesser known yet nonetheless important and provocative. In the nine graphic works that make up this seminal series, Kacharava repurposed existing photographs of Soviet politicians printed on high-quality photographic paper that, in their rebirth, not only acquire new meaning but also function allegorically in decolonial discourse.

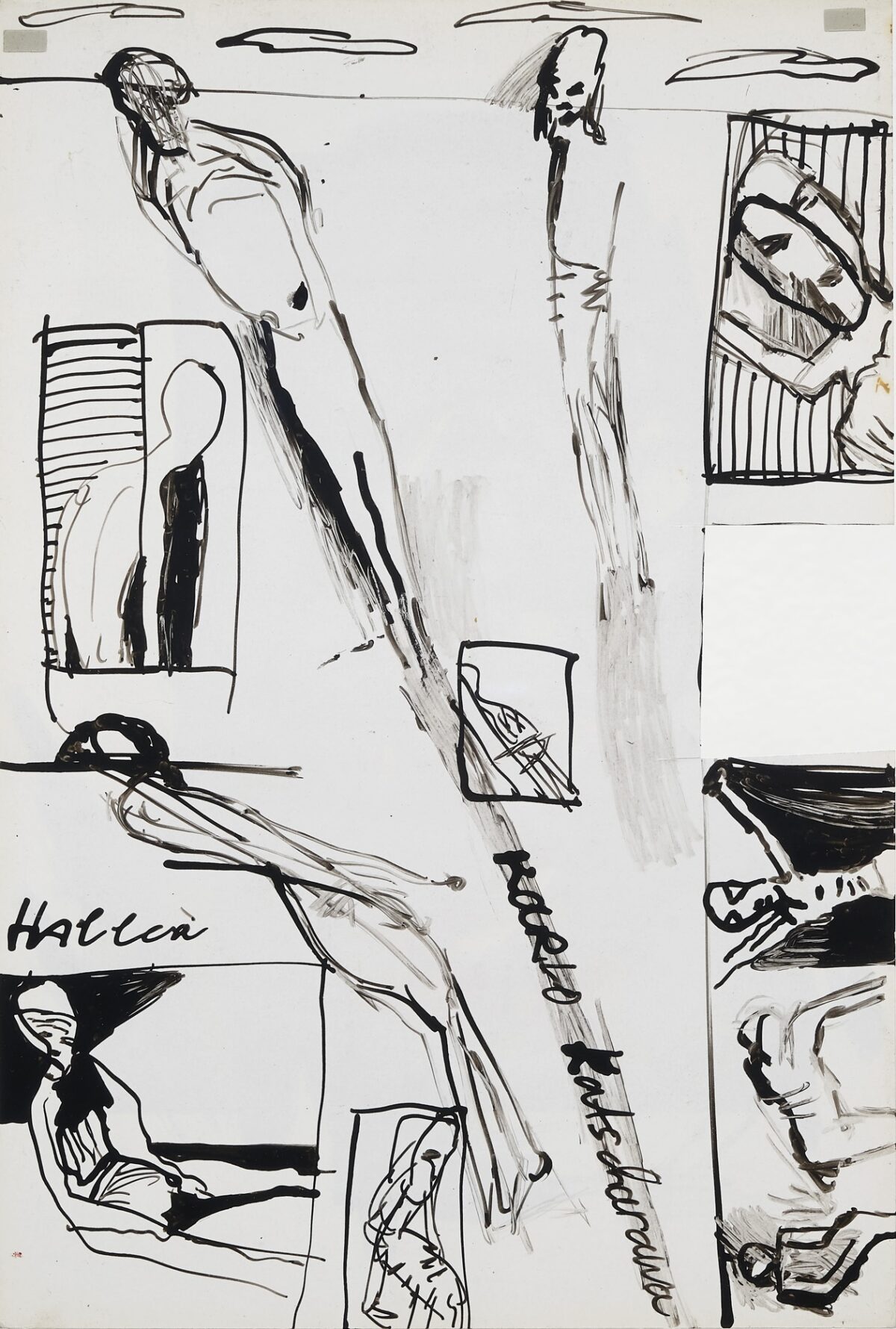

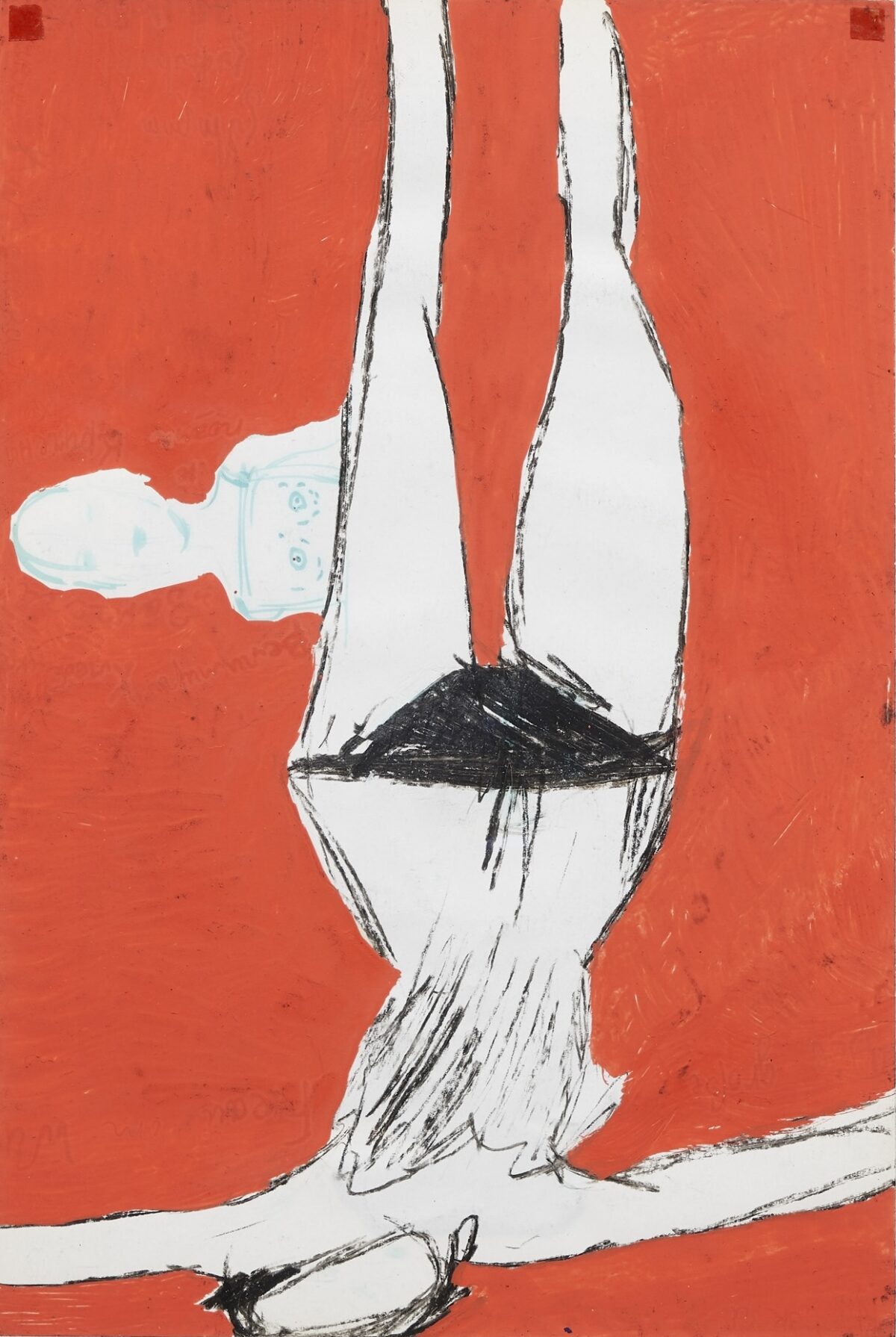

Even though Kacharava, commonly known as simply “Karlo,”4Kacharava is referred to as “Karlo” by his friends and cultural workers alike in Georgia. was a monumental figure in Georgia in the late 20th century, founding collectives in the 1980s that played significant roles in the broader Caucasus, he has only recently garnered international recognition and institutional interest. While his works are now being “discovered” and explored by transnational scholars, curators, and researchers, they have been a powerful presence, albeit unseen or perhaps effaced or otherwise hidden, for much longer. Erased Portraits of Politicians represent a prodigious example of Karlo’s storytelling—juxtaposing symbolism with endless possibilities for knowledge contribution and imagination to draw parallels with the past that connect it to the present and future. In repurposing existing photographs of Soviet politicians, the artist has presented a perfect metaphor for the double-sided nature of history. The result is a showcase of captivating drawings and graphic works posthumously exhibited in 2023–24 in the artist’s first institutional show in Europe, where they were displayed so that viewers could see both the front and back sides of each image (figs. 1, 2).5Karlo Kacharava: Sentimental Traveller, S.M.A.K., Ghent, December 2, 2023–April 21, 2024. The curatorial decision to present the works in this way accentuates their multilayered meaning, an essential aspect of the series (figs.3-8).

In contemporary discourse, the reuse or recycling of materials is considered a sustainable and environmentally friendly practice. However, in Georgia in the early 1990s, it was a necessity due to the scarcity of art supplies. Karlo was not unusual in his decision to repurpose existing materials—in this case, photographs of politicians—but how he chose to do so is nonetheless interesting. Rather than simply covering up the photographs in black to create a fresh background for his new images, the artist employed a thick brush dipped in black ink to smudge them. This technique left behind ghostly silhouettes, suggesting the presence of the individuals in the original photographs while effectively obscuring their identities. On the blank reverse sides of the photographs, he then created new drawings. Through the deliberate act of “erasing” the original portraits, and simultaneously intertwining them with his own imagery, he established a complex dialogue surrounding themes of identity, representation, and the ephemeral nature of political power. These two-sided works serve not only to critique the prominence of political figures but also to challenge viewers to consider the implications of narrative erasure. In doing so, the artist invites a reflection on those voices that can become marginalized or invisible within contemporary discourse.

“One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light but by making the darkness conscious.”

—Carl Jung6C. G. Jung, Alchemical Studies, trans. R. F. C. Hull, Bollingen Series XX (Princeton University Press, 1967), 265–66.

In a manner akin to the erasure of specific political identity enacted in Karlo’s series, Georgia’s national identity has been systematically suppressed for more than a century, resulting in enduring postcolonial trauma.7Although it is impossible to provide a comprehensive history of Georgia within a single footnote, it is crucial to acknowledge that the Georgian people endured two centuries of foreign colonial rule. The county was annexed by the Russian Empire for several decades in the 19th and early 20th centuries, followed by a short-lived period of freedom from 1918 to 1921, when it fell to the Red Army and was incorporated into the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Georgia regained its independence. During these tumultuous eras, the Georgian identity and language were systematically suppressed and erased from the collective consciousness of the Georgian people. Indeed, more than thirty years since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the people of Georgia still carry the pain of suppression. Could we potentially analyze our colonial history through the framework of Jungian theory of light and shadow? Carl Jung proposed that the latter symbolizes the unacknowledged or repressed aspects of the self. According to Jung, these elements, though often considered unacceptable or oppressed, can potentially be “resolved” or “repaired” by bringing them to the forefront of consciousness.8Carl Jung discusses his theory of light and shadow in several key works, including Aion, in which he elaborates on the Shadow self, and Man and his Symbols, in which he offers an overview of his concepts. See Jung, Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 9, pt. 2, Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, ed. and trans. Gerhard Ader and R. F. C. Hull (1951; Princeton University Press, 1979); and Jung et al. Man and his Symbols (Aldus Books, 1964). This dynamic suggests that the content of the shadow is not fixed. Can this framework give us a deeper understanding of identity and collective subconscious memory? How can we construct a decolonized and enlightened future by acknowledging and confronting the “dark shadows” of our history, and what measures can we take to prevent their recurrence? In what ways can recognizing the historical actions of colonialism and their enduring consequences assist us in transcending our nation’s distressing legacy? While these questions are hard to answer—and perhaps serve more as a simple invitation for thought than a groundbreaking means of resolving postcolonial trauma—we could mirror Karlo’s unconventional approach in our own discussion of political and/or philosophical matters.

I want to write so my texts don’t sound political or philosophical in general, but I’d rather simplify political and philosophical matters, and things like that, to the point of poetry.

—Karlo Kacharava9Lika Kacharava et al., eds., The Myth of Autobiography, trans. Nene Giorgadze Giorgadze and John William Narins (Cezanne Publishing, 2025), 190.

The transformative process of translating “political or philosophical matters” into poetic expression lies at the core of Karlo’s artistic practice—whether visual or written. Just as it is crucial to consider his poetry and other writings as integral components of his visual art, we must take his visual art into account when examining his work as a writer. Karlo commenced composing poems at a tender age, and his poetry reveals the evolution of his thought processes over the course of his lifetime. For example, “The Angel of Travels” (1987), translated below, is vividly cinematic, conveying Karlo’s emotions and capturing his anxieties at a particular moment in time. It not only reflects his fondness for German Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism, but also serves as a window into his multiverse, where his bold images blur with condensed text, evoking a wide range of emotions and their universality. Given that Karlo wrote this poem around the same time he created his series Erased Portraits of Politicians, it feels both natural and essential to highlight it here.

“The Angel of Travels”10Kacharava et al., The Myth of Autobiography, 161.

It’s hot out. You are lying in a train.

You think about many things at once—

this road, the landscape, and the houses

are a reflection of your thoughts:

what you can neither call accidental nor accept,

and what is divine, because it is auspicious,

and wistful, too, since it has passed.

Moons light heavy bridges.

This river begins your native land

and you fall asleep.

In a dream, you see:

People gather in a hall, take their seats.

They’re showing a Bergman picture.

A white labyrinth appears on the black screen.

Unexpectedly, the film is packed with action.

Actors step out of the screen into real life

and then go back into the movie.

Snow, a soliloquy, a clock,

another soliloquy.

Unhappy trepidation over

what will happen to somebody close.

The telephone, the clock again.

A train in a train.

On the lower part of the compartment ceiling

are the words: “Open-Closed.”

Lights in the moving corridor.

Flying ghostly companions

outside the window.

The hall was like some kind of weirdo movie studio.

They don’t know anything in this pavilion, either.

A sleepwalker’s piano.

Then

the father washes the feet of the son,

as if baptizing him.

O, the spinning of stars reflected in the river

And the sad angel of travels,

His brow clear, gazing down

Upon the passengers’ troubled slumber.

Just as in his poetry, which is loaded with visual references, Karlo’s paintings and drawings, and specifically his Erased Portraits of Politicians, bear deeper, hidden meanings and cryptic symbolism, some of which require local knowledge. The back side of each portrait has been, in effect, turned into a front side, a few of which depict nude women or nude couples in erotic poses. Although the political figures in the photographs have been rendered unidentifiable, to those familiar with Soviet history, they likely call to mind political propaganda and other instruments of imperial power designed to shape public narratives and manipulate perceptions. In stark contrast, Karlo’s own figures are bold, provocative, and collectively stand free from the confines of prejudice, propaganda, and censorship. These mixed-media works bridge German Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism while also encompassing the dark history of 20th-century Georgia.11Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism are linked by their common emphasis on emotional intensity, subjective experiences, and a break from realistic representation, as seen in distorted forms and nonnaturalistic color. Responding to the anxieties and social tensions of their respective eras, Expressionism addressed the concerns of the early 20th century, while Neo-Expressionism reflects the alienation and conflicts that emerged in the post–World War II period.

In his solo exhibition at S.M.A.K., Karlo’s nine drawings were presented in double-sided frames, showcasing his boldness and free-spiritedness while simultaneously evoking the political suppression that preceded them. This visual dexterity begs the question of whether the “erased” local histories in the broader transnational context might be presented and embedded in a similar way. The concept of visionary experience, as described by Carl Jung, highlights that the aesthetics of German Expressionism are fundamentally rooted in the collective unconscious.12C. G. Jung, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol., pt. 1, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, ed. and trans. R. F. C. Hull(Pantheon, 1959). In contrast to psychological art, which seeks to articulate the collective conscious, German Expressionism achieves two key goals: It “compensates the culture for its biases” by illuminating what is often “ignored or repressed,” and it may also “predict something of the future direction of a culture.”13Susan Rowland, ed., Psyche and the Arts: Jungian Approaches to Music, Architecture, Literature, Painting and Film (Routledge, 2008), 209. What if we conceptualize the smudged blackness in Erased Portraits of Politicians through a Jungian psychological framework, interpreting it as a manifestation of darkness or unconscious trauma, a representation of Georgia’s colonized past within the context of decolonization?

By acknowledging it and incorporating it into our contemporary narrative, in a way that is similar to the exhibition’s presentation of the series, we avoid merely obscuring this darkness; instead, we render it a visible, intrinsic aspect of the artwork. Engaging with this historical reality presents significant challenges and may elicit deep feelings of injustice, particularly within the current Georgian sociopolitical landscape. Nevertheless, grappling with these uncomfortable truths is essential to fostering genuine progress, to decentralizing narratives, and to facilitating collective healing and freedom from the trauma of the colonial past.

A man who continually erases the footprints that attest to his presence somewhere has a need to erase some of the footprints of his cohabitants, as well, so that they are not mistaken for his own by still others who are asleep or who have not opened the door, or who will never write you a letter.

Nobody, nobody, nothing.

— Karlo Kacharava14Kacharava et al., The Myth of Autobiography, 190.

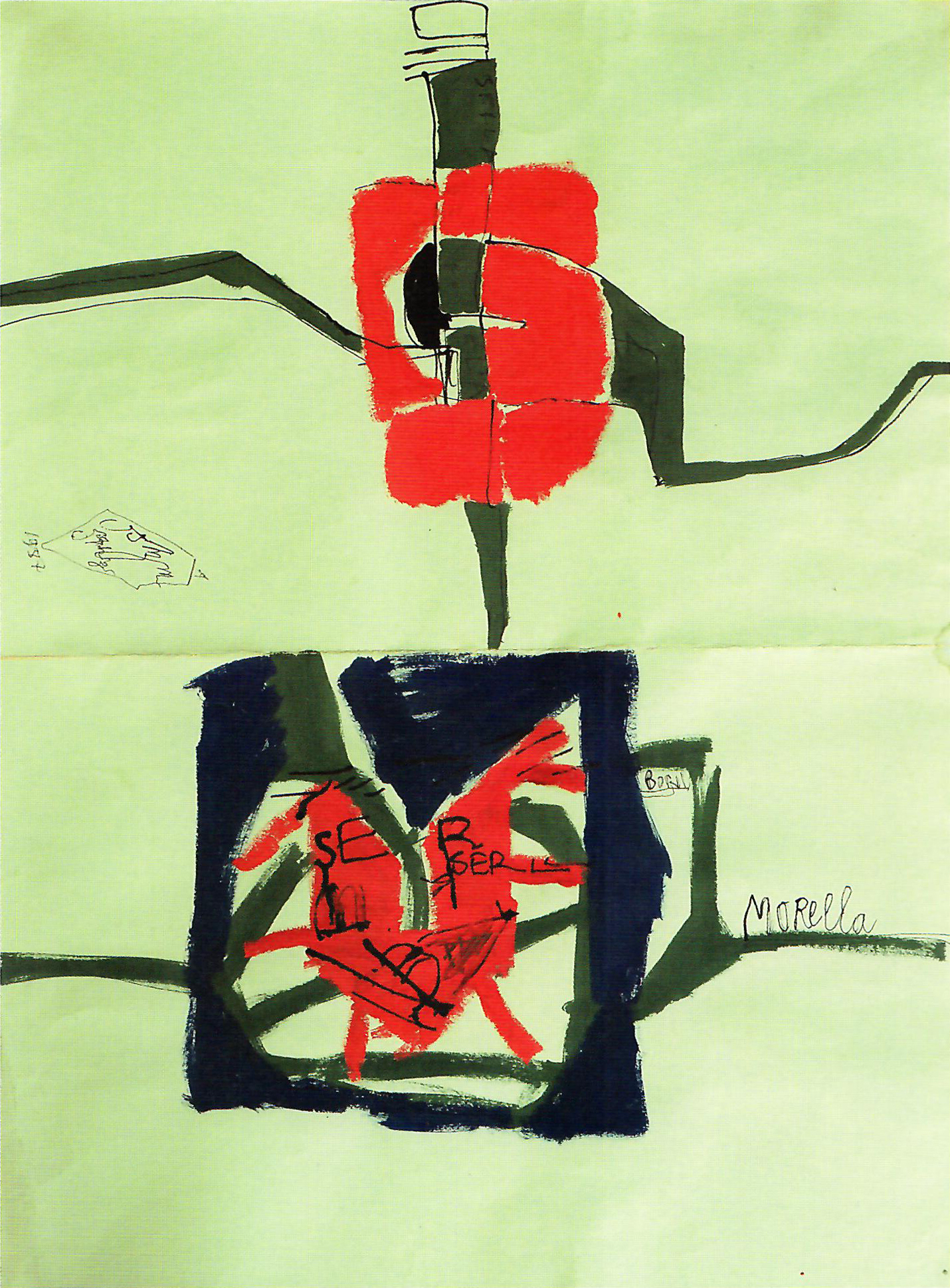

Karlo engaged with themes of constrained or erased freedom and identity within his Erased Portraits of Politicians and across his other works—including in Fahrstuhl Morella (1987), which hangs in the hallway of his home in Saburtalo, a neighborhood in Tbilisi (fig. 9). This abstract piece depicts two interwoven forms evoking elevators suspended by “ropes” in a field of seemingly unlimited light green. Executed on cardboard that has been folded in half, it can be interpreted as representing different realities coexisting within the same space—life in the Soviet Union and life outside of it—or even life and death. Moreover, it reflects the sociopolitical context in which the ability to travel beyond the borders of the Soviet Union remained, until the state’s collapse in 1991, an unattainable luxury for many. On a philosophical level, Fahrstuhl Morella probes the concept of eternal freedom, articulated as the capacity to navigate spaces devoid of borders or physical constraints. Notably, this piece, created contemporaneously with Erased Portraits of Politicians, is most likely influenced by Edgar Allan Poe’s short Gothic horror story “Morella,” first published in 1835, which explores themes of identity, death, and the uncanny resurrection of the dead. The exploration of freedom—both in metaphysical and geographical dimensions—is a pervasive motif throughout Karlo’s work.

Karlo persistently challenged the polarization inherent in the binary constructs of “us” versus “them,” which are frequently articulated through the lens of “West” versus “East” or “West” versus “Other.” His approach exemplifies a profound application of decolonial thought. Indeed, Karlo situated these categories within a horizontal, nonhierarchical framework, thereby emphasizing the intricate interconnectedness of identities within a transnational landscape. Furthermore, Karlo’s advocacy for a decentralized narrative for Georgia in the early 1990s predates the current discourse on decolonization in Georgian art history, highlighting the foresight of his perspective.15In a 1992 interview, Karlo discussed the decentralized position of Georgian artists in relation to Moscow and the Moscow art scene. He noted that Georgian artists do not want to be perceived within the Russian art scene, but rather transnationally. Karlo Kacharava, Kakha Melitauri’s video archive 1992, posted 2023 by Luka Tsethkhladze, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pyiad5GQC6o. In Jung’s analytical psychology, one recognizes that light and shadow are not mutually exclusive; rather, they coexist, often with shadow being significantly oppressed or suppressed. Acknowledging the darkness of the traumatic colonial history and incorporating it (rather than avoiding or suppressing it) may help to overcome the traumatic post-Soviet histories.

In conclusion, the journey of overcoming the postcolonial Soviet past and its accompanying trauma in Georgia is an arduous and protracted one. Engaging in discussions that illuminate these often-overlooked aspects of history and incorporating them into our daily consciousness is vital for collective healing. This necessity is particularly salient in the current political climate within Georgia, where historical narratives are frequently contested and reshaped. The recent uncovering of Erased Portraits of Politicians exemplifies this dynamic. These artworks, long obscured from view and largely unrecognized by the international art community, provide an invaluable opportunity to reflect on the mechanisms of memory, identity, and representation. By presenting both sides of the erased faces of political figures, this series acts not only as a visual statement but also as a powerful metaphor for the complexities of decoloniality. It underscores the imperative to confront the historical silencing of certain narratives and to actively reconstruct a more inclusive understanding of our past. This approach is essential for fostering a more equitable and just society, as it encourages ongoing dialogue about the layers of history that inform our present and future.

- 1William Dunbar, “The Georgian artist who was the voice of his generation,” Apollo, April 30, 2024, https://apollo-magazine.com/karlo-kacharava-georgia-avant-garde-artist-recognition/.

- 2Vija Skangale, “Karlo Kacharava: The Salient Truth of the ‘Supernova,” in Karlo Kacharava: Sentimental Traveller, ed. Irena Popiashvili, exh. cat. (S.M.A.K, 2024)

- 3Skangale, “Karlo Kacharava,” 41.

- 4Kacharava is referred to as “Karlo” by his friends and cultural workers alike in Georgia.

- 5Karlo Kacharava: Sentimental Traveller, S.M.A.K., Ghent, December 2, 2023–April 21, 2024.

- 6C. G. Jung, Alchemical Studies, trans. R. F. C. Hull, Bollingen Series XX (Princeton University Press, 1967), 265–66.

- 7Although it is impossible to provide a comprehensive history of Georgia within a single footnote, it is crucial to acknowledge that the Georgian people endured two centuries of foreign colonial rule. The county was annexed by the Russian Empire for several decades in the 19th and early 20th centuries, followed by a short-lived period of freedom from 1918 to 1921, when it fell to the Red Army and was incorporated into the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Georgia regained its independence. During these tumultuous eras, the Georgian identity and language were systematically suppressed and erased from the collective consciousness of the Georgian people.

- 8Carl Jung discusses his theory of light and shadow in several key works, including Aion, in which he elaborates on the Shadow self, and Man and his Symbols, in which he offers an overview of his concepts. See Jung, Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol. 9, pt. 2, Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, ed. and trans. Gerhard Ader and R. F. C. Hull (1951; Princeton University Press, 1979); and Jung et al. Man and his Symbols (Aldus Books, 1964).

- 9Lika Kacharava et al., eds., The Myth of Autobiography, trans. Nene Giorgadze Giorgadze and John William Narins (Cezanne Publishing, 2025), 190.

- 10Kacharava et al., The Myth of Autobiography, 161.

- 11Expressionism and Neo-Expressionism are linked by their common emphasis on emotional intensity, subjective experiences, and a break from realistic representation, as seen in distorted forms and nonnaturalistic color. Responding to the anxieties and social tensions of their respective eras, Expressionism addressed the concerns of the early 20th century, while Neo-Expressionism reflects the alienation and conflicts that emerged in the post–World War II period.

- 12C. G. Jung, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, vol., pt. 1, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, ed. and trans. R. F. C. Hull(Pantheon, 1959).

- 13Susan Rowland, ed., Psyche and the Arts: Jungian Approaches to Music, Architecture, Literature, Painting and Film (Routledge, 2008), 209.

- 14Kacharava et al., The Myth of Autobiography, 190.

- 15In a 1992 interview, Karlo discussed the decentralized position of Georgian artists in relation to Moscow and the Moscow art scene. He noted that Georgian artists do not want to be perceived within the Russian art scene, but rather transnationally. Karlo Kacharava, Kakha Melitauri’s video archive 1992, posted 2023 by Luka Tsethkhladze, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pyiad5GQC6o.