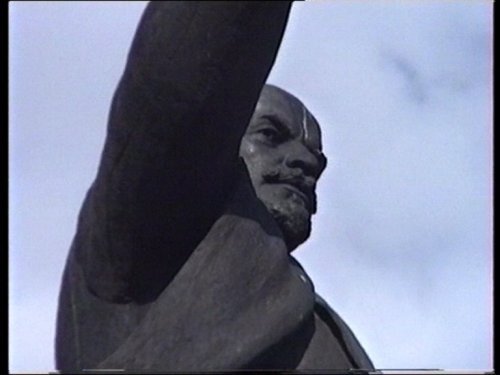

Once in the XX Century, an eight-minute film by Deimantas Narkevičius shows a larger-than-life statue of Vladimir Lenin being erected in Vilnius’s main square to the cheers of a large crowd. MoMA acquired the film in 2011, and in 2013, it was included in the Museum’s Performing Histories (1), an exhibition of recent time-based art exploring the facts and fictions of history. Narkevičius made the work in 2004, more than a decade after the statue was taken down and a half-century after it was dedicated, in the early 1950s.1The statue was removed in 1991, the year after Lithuania became the first republic to declare independence from the Soviet Union.

Using footage of the statue’s removal, which he obtained from the Lithuanian National Television Archive and from a freelance videographer, the artist reversed the image sequence so that the monument appears to be being reinstalled rather than dismantled. Thus, an action long associated with the drawing of the Iron Curtain is critically subverted, drawing the viewer’s attention to the carefully constructed nature of history. Unlike his successor, Joseph Stalin, whose dictatorship was denounced and image purged in 1956, Lenin was revered throughout the Soviet Union until, and in some places, even after, its dissolution.

Through the presentation of conspicuously edited documentary footage, Narkevičius conflates two disparate historical moments—the raising and the removal of the Lenin statue—in a film rife with ambiguities and anachronisms. The XX in the title can be read as the Roman numeral twenty or as a placeholder for a time unknown, or for any time. In the film, the juxtaposition of the tricolor flag of independent Lithuania with the richly patinated surface of the monument confounds any attempt to situate the film temporally, destabilizing the viewer’s perception of time in the film. Narkevičius comments on this effect: “For me, it’s interesting to make it possible for film to not fix a document, for the images to be unplaceable, uncertain to some extent, for the audience to be unsure exactly when or how or who they were made by.”2Martin Clark, “Deimantas Narkevičius and Martin Clark in Conversation: Starr Auditorium, Tate Modern 24th October 2004,” in Deimantas Narkevičius: Once in the XX Century (Bristol: Arnolfini, 2006), p. 51. In Once in the XX Century, he purposefully exposes and exaggerates inconsistencies in the film’s narrative in order to parse the problematic relationship between history and ideology in the Soviet era.

In Once in the XX Century, Narkevičius employs reverse play along with montage and the point of view of a handheld camera. These techniques echo the practices of Sergei Eisenstein and other avant-garde filmmakers of the early twentieth century. Eisenstein’s October, a print of which is in MoMA’s collection, was made in 1928 to commemorate the Russian Revolution. In the film’s opening scene, the statue of Alexander III, located in front of Moscow’s Christ the Savior Cathedral, is violently toppled by a roaring crowd. Later in the film, when the fate of the Revolution seems uncertain, the statue appears to reassemble itself. Both Eisenstein and Narkevičius use well-known statues of political figures—symbols of power, stability, and continuity—to play with temporality, compelling the viewer to question how history is constructed, inscribed, and recalled.

The Lenin statue seen in Once in the XX Century can be found today eighty miles outside Vilnius, in Grūtas Park, Lithuania’s graveyard for Soviet monuments. Almost twenty-five years later, other statues of Lenin continue to fall across the former Eastern Bloc in a phenomenon known as Leninopad, or the felling of Lenin.3Leninopad is a compound word, combining the name Lenin with the verb to fall падать (padat’) in Russian or падати (padaty) in Ukrainian. A list of destroyed statues and related infographics can be found on the website “Lenin Statues” During the recent Euromaidan Revolution in Ukraine, the destruction of Lenin statues surged in December 2013, when protests against former President Viktor Yanukovich reached a peak.4The Euromaidan Revolution began in November 2013 with peaceful protests on Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Kyiv’s central square, after Yanukovich refused to sign the EU Association and Free Trade Agreements that would distance Ukraine from Russia’s influence. By February 2014, the protests were marked by violence, resulting in thousands of injuries, hundreds of arrests, and over 100 associated deaths. This was Ukraine’s second post-Soviet revolution, after the Orange Revolution in November 2004. The toppling of these statues were captured in countless photographs and videos that were widely circulated in the international media.

The felling of Lenin—then, after the fall of the Soviet Union, and now—must be viewed within the larger discourse of public memory in Eastern Europe, since this action provides an immediate and powerful means of rewriting the region’s already fragile historical narratives. In this context, one can view the destruction of Lenin statues not as a radical gesture but as part of the ineluctable ebb and flow of history. Vulnerable to the fluctuating environment to which they are bound, monuments and memorials provide us with a false sense of historical closure. Although made of stone, they are only as permanent as the consensuses that built them. Following Narkevičius’s lead, we too, should critically deconstruct and reconstruct established histories in order to build new monuments for the future.

- 1The statue was removed in 1991, the year after Lithuania became the first republic to declare independence from the Soviet Union.

- 2Martin Clark, “Deimantas Narkevičius and Martin Clark in Conversation: Starr Auditorium, Tate Modern 24th October 2004,” in Deimantas Narkevičius: Once in the XX Century (Bristol: Arnolfini, 2006), p. 51.

- 3Leninopad is a compound word, combining the name Lenin with the verb to fall падать (padat’) in Russian or падати (padaty) in Ukrainian. A list of destroyed statues and related infographics can be found on the website “Lenin Statues”

- 4The Euromaidan Revolution began in November 2013 with peaceful protests on Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Kyiv’s central square, after Yanukovich refused to sign the EU Association and Free Trade Agreements that would distance Ukraine from Russia’s influence. By February 2014, the protests were marked by violence, resulting in thousands of injuries, hundreds of arrests, and over 100 associated deaths. This was Ukraine’s second post-Soviet revolution, after the Orange Revolution in November 2004.