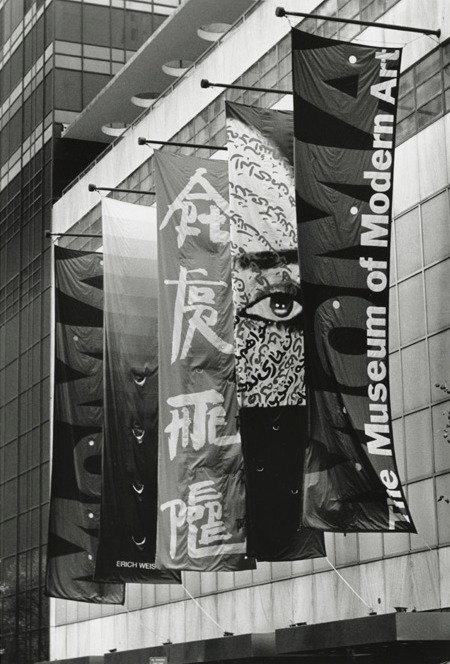

Last updated on Jun 3, 2014. First published on December 19, 2013. Deconstructing the past was the main concern of Chinese artists in the 1980s. Firmly believing that they could distance themselves from traditional and official art by studying Western art movements, artists participated in discussions, of Dada, Pop art, and other major currents, in art journals and personal correspondence. The artists’ social and cultural remove from both Chinese tradition and Western modernism rendered them cultural nomads and influenced their ideas and interpretations. Today, their hybrid art reflects their distinct approach to the West and has become an integral part of the global art panorama. Among the heralds of this new era in Chinese art was a site-specific work by Xu Bing displayed at Projects 70: Banners I at MoMA in 1999, at which the artist introduced his invention of New English Calligraphy—English words written and structured in images resembling Chinese characters. On the facade of the museum, Xu hung a banner inscribed with the words “Art for the People,” a paraphrase of Chairman Mao’s famous quote “Art serves the people.” This marked the start of a transcultural dialogue in contemporary art.

post is releasing a series of primary documents drawn from the writing of Chinese artists, which presents the original sources in Chinese along with first-time English translations. These distinctive readings of Western art are an extension of an earlier MoMA project, published in 2010 as Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents. The materials offer insight into interactions in art that transcend time and place.

Edited by Yu-Chieh Li

Source contents

Duchamp Stripped Bare by the Chinese, Even: Rewriting Example No. 5 or A Discussion of the Duchamp Phenomenon

By Huang Yong Ping 黄永砯, 2007 (Written in 1988)

Publication: ’85 New Wave Archives II

Publisher: Beijing Shiji Wenjing Publishing House

Language: Chinese

In light of the death of the old earl, the youngster comes into inheritance; however, this is not the whole truth. In history, a pause is created, and the agent steps into nothingness. —Anonymous 1This quotation is difficult to trace without the artist’s help. After the Cultural Revolution, Chinese students became avid readers of works of Western philosophy and literature translated into Chinese. The Chinese editions were carefully screened by the government and often contained imprecise or incomplete bibliographical references to their sources. The fact that few copies of these translations are in circulation today adds to the challenge of identifying the editions on which they are based. Huang Yong Ping noted in his notes that he read Shu Weiguang’s book about Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy in 1982, a biography of Wittgenstein in the mid-1980s. Read more (in English) about the “reading fever” of the 1980s in interviews conducted by the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong: http://www.china1980s.org/en/interview.aspx (YL)

Duchamp died in 1968; I am writing this article in 1988. Even twenty years after his death, Duchamp is still frequently mentioned; in a sense, he is still alive. Would it be at all possible for us not to mention him any longer—to let him truly fade away? Perhaps it would, perhaps it wouldn’t; in any case, my reason for writing this essay is to prevent myself from mentioning him in the future. So that Duchamp can be written off our books, just as many others have been. However, this cannot guarantee that Duchamp will be truly put behind us. There is one way to deal with this issue, and that is by killing all of Duchamp’s disciples. Then he will finally die. This is our mission today but that might not suffice. We must also kill all of his opponents to prevent his name from ever being mentioned again. People will only cease to write or comment on him when all those who want to hear about him are dead. Many fictional figures (who have names) found in history books are often mentioned in today’s publications because they are used as counterexamples, as if they truly existed. Having said that, the example we are concerned with here [Duchamp] is real. There are two interpretations of the two characters in the name Du Xiang, which is the Chinese translation of Duchamp. The first character, du, generally has two meanings. First of all, it might be a family name. The family name comes before the given name in Chinese and thus resembles a prefix. Its second meaning is “obstruction” or “prohibition”; it also refers to something that is fictional. Here, of course, it is the first meaning that applies. “Xiang” could mean “elephant,” “image,” or “form.” It also means “copying” or imitating. “Hao xiang” also means “seem” and is an equivocal expression that Duchamp liked to use:

“I don’t ascribe to the artist the sort of social role in which it seems like he is indebted to society and so he feels obligated to achieve something. This is a horrifying perspective.” (p. 79)

Why do we “pull out” Duchamp instead of a dead horse? Getting the horse onto the road might help nurture our brains. In today’s literature, all sorts of characters get pulled out and cited: Dong Qichang, Dong Cunrui, Zengjiasso, Bi Guofan, Laoni, Tzschezi, and so on. We pull them out in order to be able to insert them. In a way, pulling out and inserting are one and the same thing; this corresponds to what a text needs: if you don’t pull out some names, then at least quote some sentences. Hence, people today, whether rich or poor, can barely be considered alive without being placed in relation to the dead. “Those who do not want to be in the company of the dead are condemned to die.” This is a rephrasing of Santayana’s “Those who do not study the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Rejecting parents as a system.

“Question: ‘As far as I know, your mother was also an artist. She painted still lifes, didn’t she?’ Answer: ‘She even wanted to cook them, too, but in her seventy years of life, she was never really in touch with art. She did some Strasbourgs on paper. It never went any further.’” (p. 11)2The page numbers cited in this article refer to the Chinese edition of Pierre Cabanne’s Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971), which was originally published in French under the title Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (Paris: Editions Pierre Belfond, 1967). The Chinese version, issued by Art Publishing Co., Taiwan, in 1986, was translated from the English by Zhang Xinlong. All quotations from Cabanne’s book that appear in this article are translations of Huang Yong Ping’s citations from the Chinese edition. (Copies of the Chinese edition were available in the Guangdong region through Hong Kong. Dialogues was not the first source on Duchamp to enter China, but it was influential among artists, especially to those in the Xiamen Dada Group.) (YL)

“That is correct.” (p. 51)

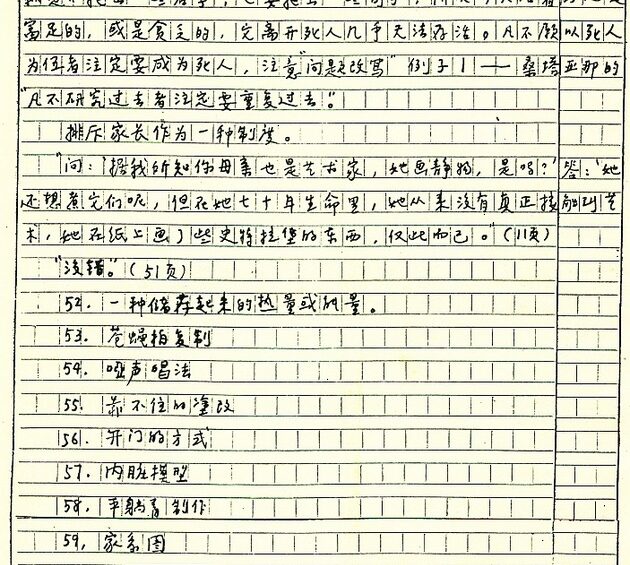

52.3This numbered list contains a selection of the 384 instructions for artworks that Huang Yong Ping inscribed on the disk of his Big Roulette Wheel (1987). The artist developed them after reading Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and Pierre Cabanne’s Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. (YL) A kind of stored heat or kinetic energy

53. Duplicating a flyswatter

54. The celostomia singing technique

55. Unreliable modification

56. Ways of opening a door

57. The inner model

58. Creating art in a lying-down position

59. Family tree 60. Weighing the weight

61. Liquid solidifying quickly

62. Heating and duplicating

63. Machinery that opens things up

64. Making a mannequin (anatomy)

65. Squeezing out a new path

66. Difficulty recognizing left from right

67. A fast knot

68. To annul ( )

69. Leaning against the mirror and looking into it

70. Checking the drawers

71. The opening of an envelope

72. Pasting paper onto the wall

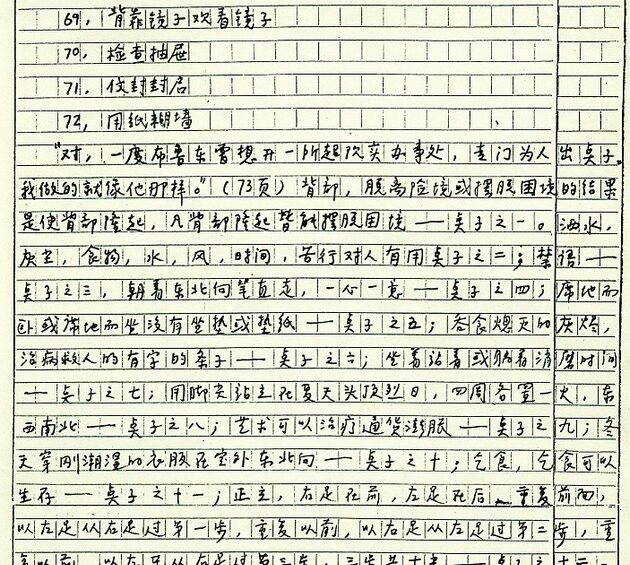

“Right, Breton once planned to open up a Surrealist office, to offer people ideas. What I was doing was similar to this.” (p. 73)

The back: The consequence of getting out of a crisis or a difficult situation is to end up becoming a hunchback; thus, having a hunched back enables one to escape from a predicament—idea number one. Watering, dust, food, water, wind, time, and austerity are helpful to people—idea number two. No talking—idea number three. Walk straight northeast—idea number four. Lie down or sit directly on the ground without relying on a cushion or a piece of paper—idea number five. Swallow the ashes of the medical prescription form—idea number six. Sit, stand, or lie down to pass time—idea number seven. Stand on tiptoe under the fierce summer sun; bonfires should surround you in four directions (north, south, east, west)—idea number eight. Art can cure inflation—idea number nine. Put on wet clothes in winter and stand outdoors in the northeast corner—idea number ten. Beg for food; begging is a way to survive—idea number eleven. Stand upright with your right foot in front of the left and do three moves: first advance the left foot and place it in front of your right foot; second, bring up the right foot and place it in front of your left foot; third, advance the left foot and again place it in front of your right foot; these three steps equal a distance of seven meters—idea number twelve. Here the possibilities that stem from “sub-sorcery” and “sub-performances” are the most crucial. Sorcery enables you to avoid originality and concentrate on duplication and transmission, whereas sub-performances constitute threatening behavior.

“Surely, in all the discussions about paintings, Manet’s name comes up more often than not. And Cézanne, to most people, is just a piece of meat in a pot of stew.” (p.13)

Conversing—tactics, eating—consuming; before we articulate those many names we must undergo a process of consuming them first. This is what our throat does. On the one hand, it has the esophagus; on the other, it has the articulation of language. More often than not, we exhale more than what we inhale.

“It is just that the old habits keep them on the track of making one painting each and every month, all this. . . . They think that it is as if they owe society an artwork each month or each year.” (p. 100)

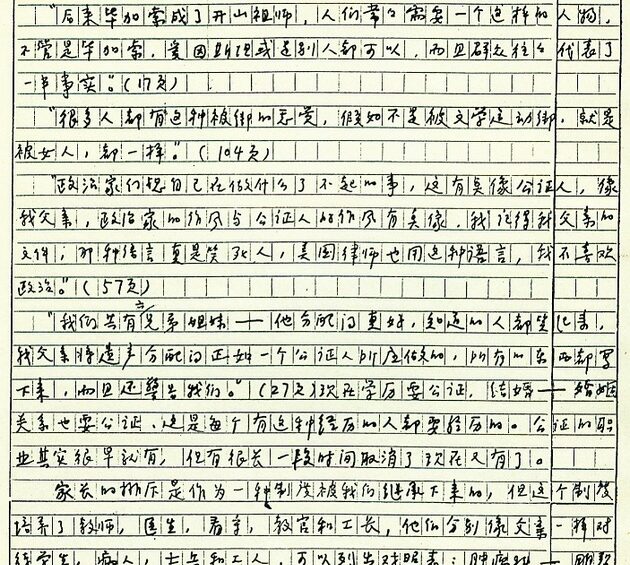

“Later on Picasso became a pioneer of a kind. We often need such a character, be it Picasso, Einstein, or anybody else—and the crowd often speaks for half of the whole truth.” (p. 17)

“Many people feel as if they are being constrained by something. If not by some literary movement, then by some woman, but in the end, it’s all the same feeling.” (p. 104)

“Politicians imagine that they are doing something extraordinary! It’s a little like a notary, or like my father; politicians and notaries have similar styles. I remember my father’s documents, the language was ridiculous. American lawyers employ such language as well, and I must say I dislike politics.” (p. 57)

“The are six siblings in my family. When it came to inheritance, my father did a remarkable job, so good that everyone who heard about it was amused. My father split the inheritance into six portions, just like a notary would, and had everything written in ink on paper, along with warnings for us all.” (p. 27) Nowadays everything goes through a notary. A diploma needs to be certified by a notary, getting married—the marital relationship—also needs to be certified by a notary; this is what we all go through if we ever have such experiences. In fact, the notarial profession existed long ago but disappeared for a long time until it came back to existence.

Parents’ veto power is something that our social system has passed down from generation to generation. However, the same system has given us the chance to train teachers, doctors, officers, guards, drillmasters, and foremen, who play the role of father figures for students, patients, soldiers, and workers, respectively. We can draw up a comparative list as follows: oncology clinics—the department of sculpture—the faculty of chemistry—arsenal factory; dermatology clinics—the department of oil painting—the department of Chinese literature—latex workshop; pediatric clinics—the department of ink painting—the faculty of mathematics—cookie factory; stomatology clinics—department of art history—department of foreign languages—shoe and hat factory.

“No, one must live on; I am penniless, and I must earn my living. A man has got to eat, and that is different from painting for the sake of painting. One can certainly pursue both doings at the same time without any conflict.” (p. 72) Dieting or simply eating less can help stimulate the digestive system, and this is very important—recommendation number thirteen—in any case, eating nothing in order to follow the Daoist practice of fasting requires a certain amount of training. By practicing the Daoist breathing method, one reaches a state of “embryonic respiration” (the breathing of a child in its mother’s womb). This is suggestion number fourteen: “eating air” or “drinking water.”

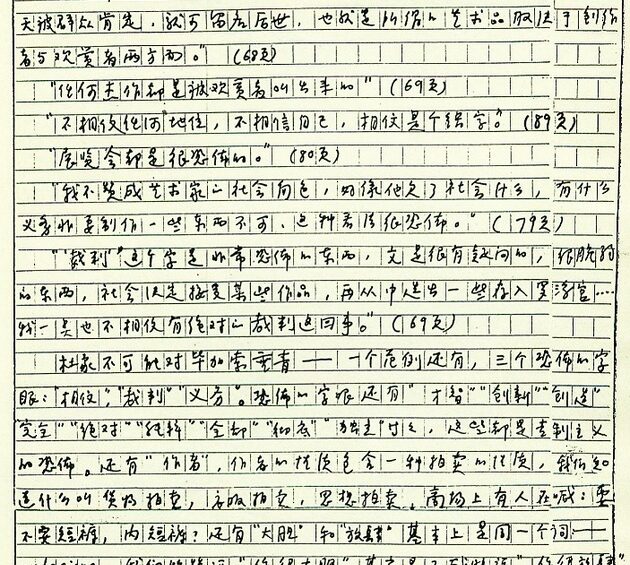

“I firmly believe in artists being a medium. An artist creates art hoping that one day it may be recognized by the world, leaving his name on a page in history. This is why we say that the value of an artwork depends on both the creator and the audience.” (p. 68)

“Any masterpiece is only a masterpiece because the audience says so.” (p. 69)

“Not believing in status, not believing in oneself, makes belief a misnomer.” (p. 89)

“Exhibitions are horrific places.” (p. 80)

“I don’t agree that artists bear social responsibility, as if they owe something to society and must take on the duty of creating something. This is a horrifying idea.” (p. 79)

“The word ‘judgment’ is such a terrible idea. It’s weak and problematic. That a society wields the power and right to decide whether to accept certain works, and then to select a few of them to send to the Louvre. . . . I don’t believe at all in such a thing as absolute judgment.” (p. 69)

Duchamp will never be a fan of Picasso. Here are some examples. Three terrible words: “belief,” “judgment,” and “obligation.” Further frightful words include “intelligence,” “creation,” “innovation,” “perfection,” “absoluteness,” “purity,” “totality,” “thoroughness,” “independence,” and so on—these all represent the terror of totalitarianism. There is also the word “author.” There is something about the nature of an “author” that can be observed at an auction. We all know what an auction is: there are, for example, clothes auctions and idea auctions. Sellers yell, “Shorts? Underpants?” Besides, “bold” and “impudent” both mean “audacious.” When we compliment someone by saying, “You are bold,” we are actually implying “You are imprudent.” The word “dictation” is also frightful for people who have to record words—all dictators are people who dictate. In addition, “dictionary,” “dictum,” “dictation,” and “dictate” have the same prefix: “dict.” “Neo” is a prefix used with great care: “Neo-Expressionism,” “Neo-Kantism,” “Neo-Duchampism.” Of course, there is also the prefix “post.” “Neo,” or “new,” means that something is being used for the very first time: new clothes, a new house, a newlywed woman; the fact that a bride is no longer a virgin could cause a difficult situation. Neo-Expressionism is not the earliest form of Expressionism; this is another difficult situation. Of all the words we have, the most frightful must be “preface,” which starts with the prefix “pre.” A preface is the start of something, such as opening remarks; it is “premier,” “predominant,” “preferment”; it is similar to the status of a university “president”; it is the “premise” of all and is “predictable,” predetermined,” “predecessor,” “preclude,” “prepuce”; it is like a “premature” baby is “precocious”; it is also a “prescribed,” “premarital,” “preconceived,” “precast,” and can be “prejudicial.” All prefixes and prepositions are horrible.

“Picasso is like a powerful lighthouse. He satisfies the audience’s need for a celebrity, and as long as he can keep up that energy, it might as well be good.” (p. 94)

“Question: ‘When Picasso completed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, were you aware of the revolutionary milestone that painting was going to mark?’ Answer: ‘Not at all. We never saw Les Demoiselles. It was not on display until several years later. As for myself, I discovered Cubism when I happened to visit some gallery.’” (p.16)

Generally speaking, people tend to ask for what they do not possess; if they ask for a child, it suggests they don’t have a child. Therefore, a fortune-teller can safely assume that the person who asks is the one in need. And those who seek or ask are often anxious. So if an old widow seeks a second marriage, her children might be unfilial.

“I realized that there are a lot of things people shouldn’t burden their lives with, such as busywork, a wife, vacation houses, new cars, and such. And I came to this realization early in my own life, which is why I stayed single for a very long time, so that I could avoid such mundane, everyday problems.” (p. 6)

“In 1916, when Michael Knoedler came to New York and saw Nude Descending a Staircase, he offered me $10,000 per year in advance for my future works, but I refused. It wasn’t that I was affluent, in fact I could actually have used the money—$10,000 a year—but no, somehow I felt a threat, a kind of danger that I had been avoiding up to that point. By 1916 I was already twenty-nine years old, old enough to protect myself.” (p. 109)

“When I wrote about Picasso, I said that each and every time in history, the crowd always needs a superstar, be it Einstein in the world of physics or Picasso in the world of art. Crowds and audiences bear such quality.” (p. 83)

“Moreover, I have never really strived to create or felt desperate to push myself to express anything; I’ve never had such a need to paint and create relentlessly from morning to afternoon to night.” (p. 6)

“Anti-art. Basically, it means questioning the artist’s behavior. Feeling as if his technique and some traditional things are absurd.” (p. 51)

There is also the problem of rewriting. The act of rewriting can be comparable to the form of adoption in which a child is transferred from one family to another. “If you don’t possess a stick, I’ll take it away. If you possess a stick, I’ll give you another” (an example found in Chan Buddhism). One way to rewrite this is, “If you have art, I’ll give you art. If you don’t have art, I’ll take it away.” Another example: “Art is a type of politics with colors” (by anonymous) can be rewritten as “Non-art is a type of politics without colors.” One more example: “Art is dead. Dead, but still moving forward; still moving forward, but dead” (by anonymous) can be changed to “Our late father is still with us; he is still with us but dead” (Donald Barthelme).

“Any masterpiece is only a masterpiece because the audience says so.” (p. 69)

“I firmly believe in artists being a medium. An artist creates art hoping that one day it may be recognized by the world, leaving his name on a page in history. This is why we say that the value of an artwork depends on both the creator and the audience.” (p. 68)

In order to destroy art, the audience needs to be annihilated first; an artist or a work of art without an audience is like a street beggar who begs for affection. So why interview Duchamp?—I mean the critic who wrote that book—and why do I want to write this article?—I mean myself. The spectator, translator, and commentator rely on Duchamp for earning remuneration. Thus, it is not that artists only benefit from spectators and critics. It is also unlike what Duchamp said: “Why would you pursue it? You can’t make money from it.” (p. 36).

“I signed Mutt’s name on it to avoid any personal connection.” (p. 49)

The abbreviation for antes de comer, a.c., which is used in medical prescriptions, means that such medicine should be taken before a meal. The handwriting of doctors is always illegible when they write out prescriptions and sign their names, as if the purpose were to prevent the patient from understanding anything from a non-doctor’s point of view. The doctor’s sloppy handwriting on the prescription form actually suggests how proficient he is in his job because he has done it so many times and also implies how such proficiency in this profession is not easy to attain. Being familiar with one’s job and carelessness are both the “child” and the “midwife” of customs. A signature represents “the person himself,” but an original work does not represent “the person himself.” Therefore, an original work cannot be attributed to the person who inscribes the signature, but rather to the person whose name is written there, because the person who signs the name can be separated from the name that is signed.

Duchamp’s work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even was finished between 1915 and 1923. In 1960 in London, the publication of Richard Hamilton’s book The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even4Possibly the book The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even; a Typographic Version by Richard Hamilton of Marcel Duchamp’s Green Box translated by George Heard Hamilton (London: 1960). (YL)—marked a fourth instance of rewriting.

It was only twenty-one years [after the death of Duchamp] that by chance I had an opportunity to visit the homeland of the creator of The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even.5When Huang was writing this article in 1988, he knew that he would participate in Magiciens de la terre at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1989. (YL) ”

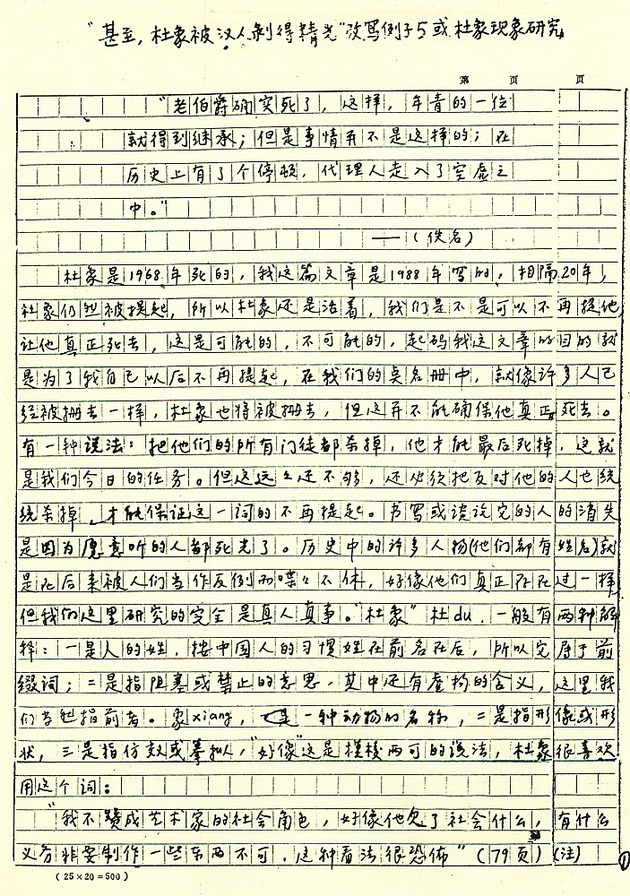

The text is translated from the Chinese by Lina Dann and Yu-Chieh Li, annotated by Yu-Chieh Li. Read Huang Yong Ping’s manuscript to the Chinese text here.

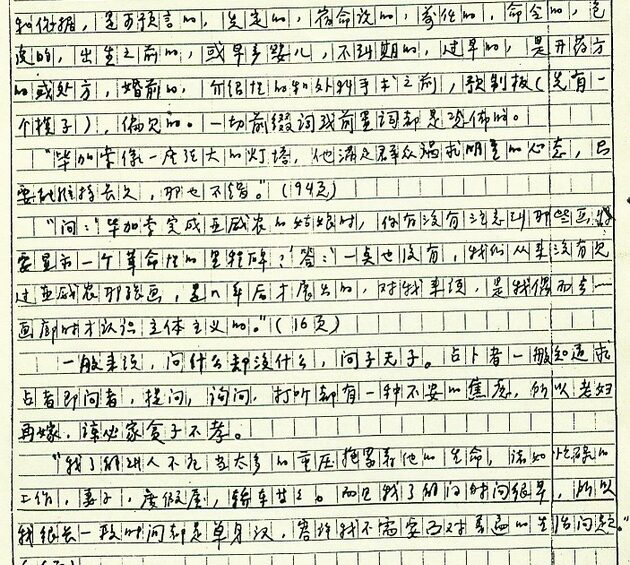

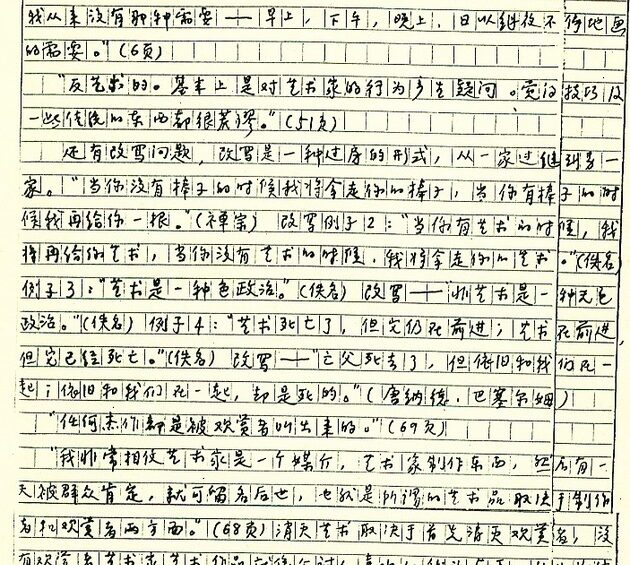

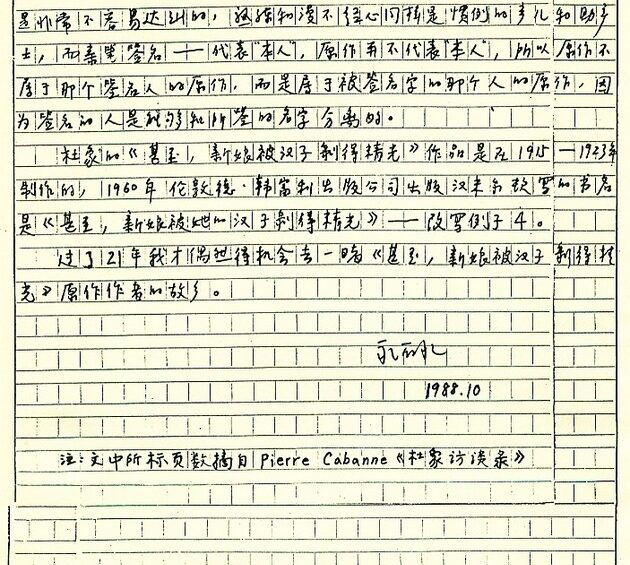

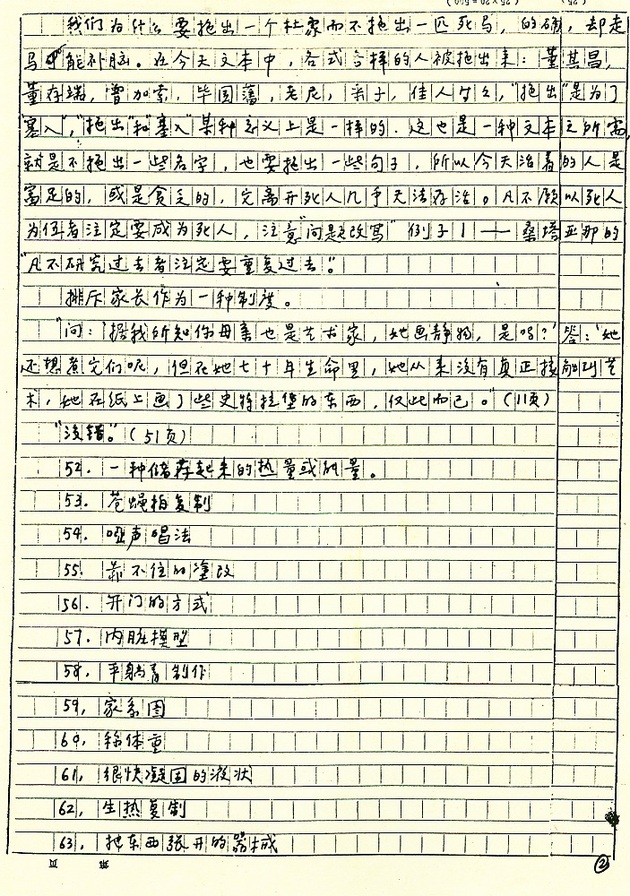

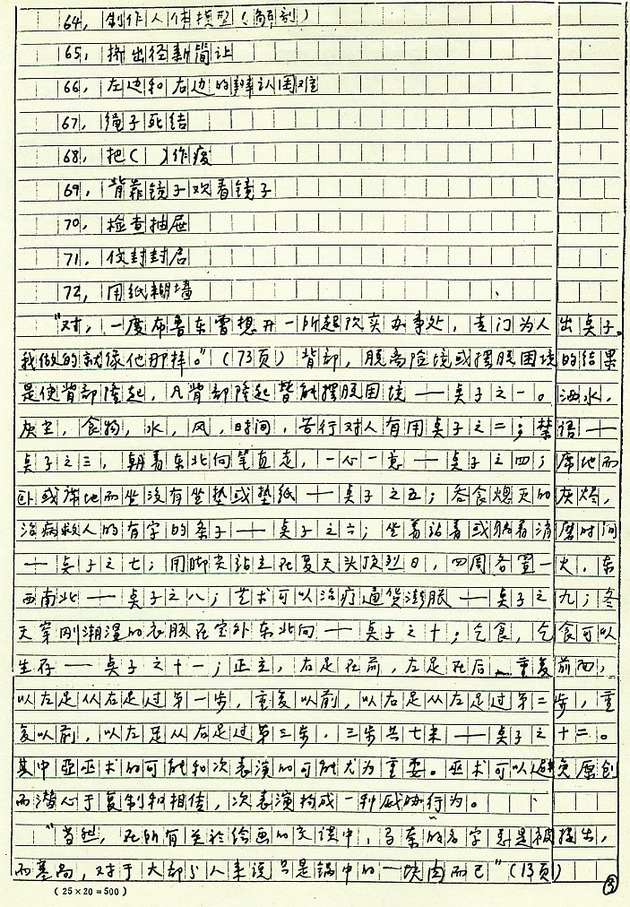

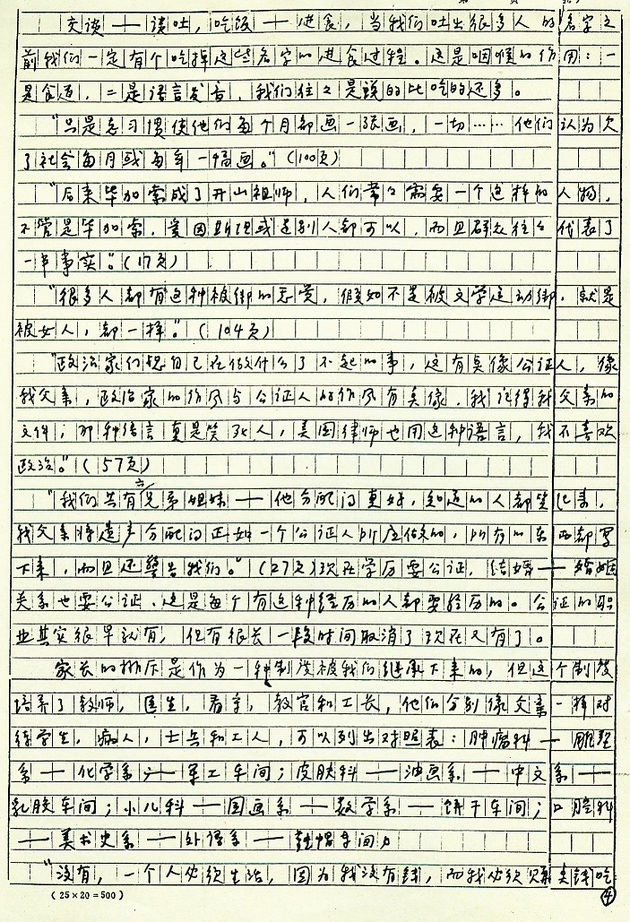

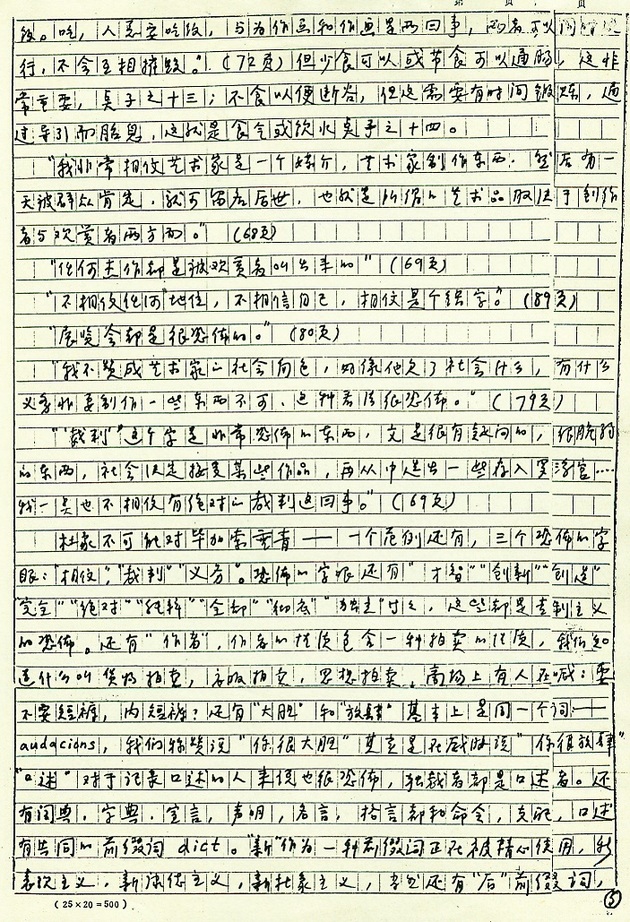

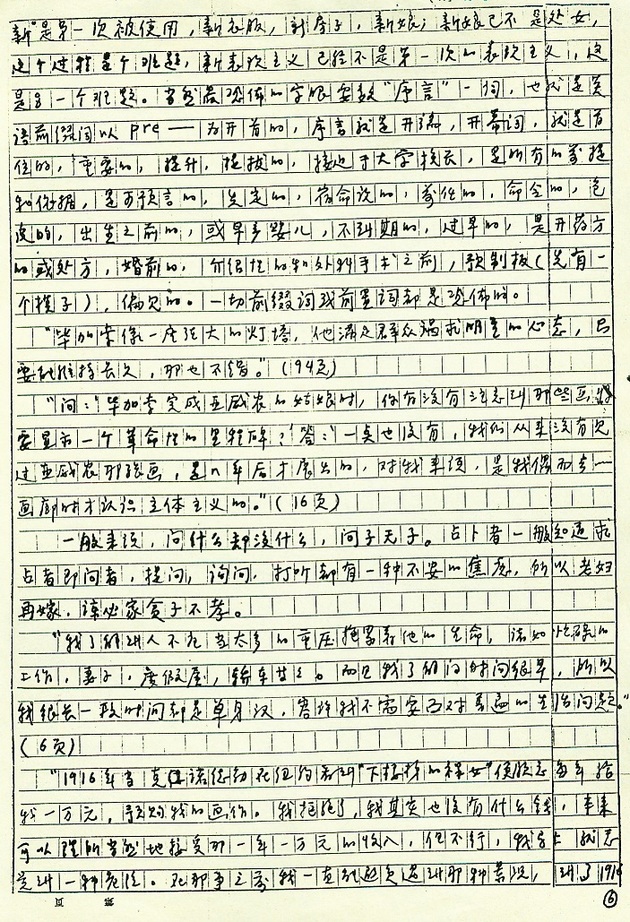

“甚至,杜象被汉人剥得精光” 改写例子5或杜象现象研究

By Huang Yong Ping 黄永砯, 2007 (Written in 1988)

Publication: ’85 新潮档案 II

Publisher: 北京世纪文景文化传播有限公司

Language: 中文

These are images of Huang Yong Ping’s manuscript to the text. Image courtesy of Huang Yong Ping and Fei Dawei.

Read the english translation here.

On Andy Warhol: Perhaps Simplicity Outshines Complexity

By Wang Guangyi 王广义, October 9, 2013, Narrated by Wang Guangyi, Compiled by Li Jianya. Translated by Lina Dann and edited by post editors.

Publisher: www.bjnews.com.cn

Language: Chinese

Links: http://epaper.bjnews.com.cn/html/2013-10/09/content_469676.htm?d

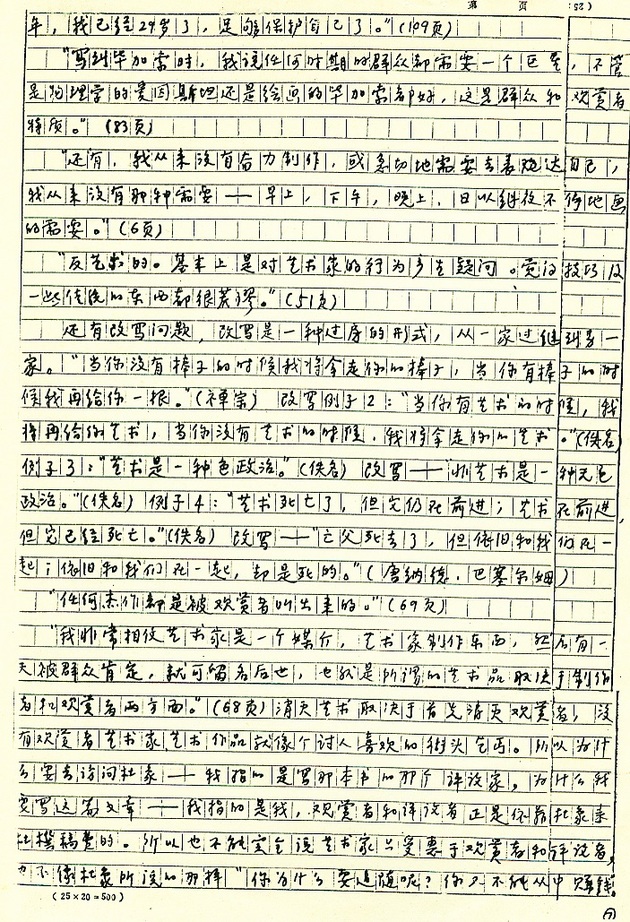

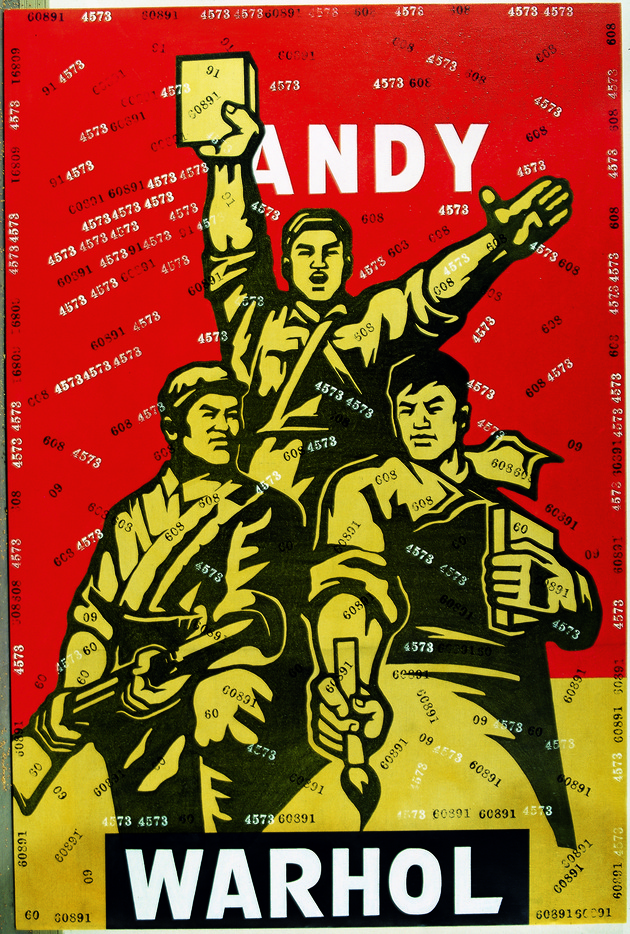

Andy Warhol Makes the Ordinary Even More Ordinary

Back in college, I came across Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys almost simultaneously. The first work of Andy Warhol I ever saw was his Marilyn Monroe. It was so simple and so untouched by artificiality, without any trace of “painting.” It was in a sense perplexing, but still, I knew that the adoration I felt for Marilyn Monroe had arisen from the bottom of my heart.

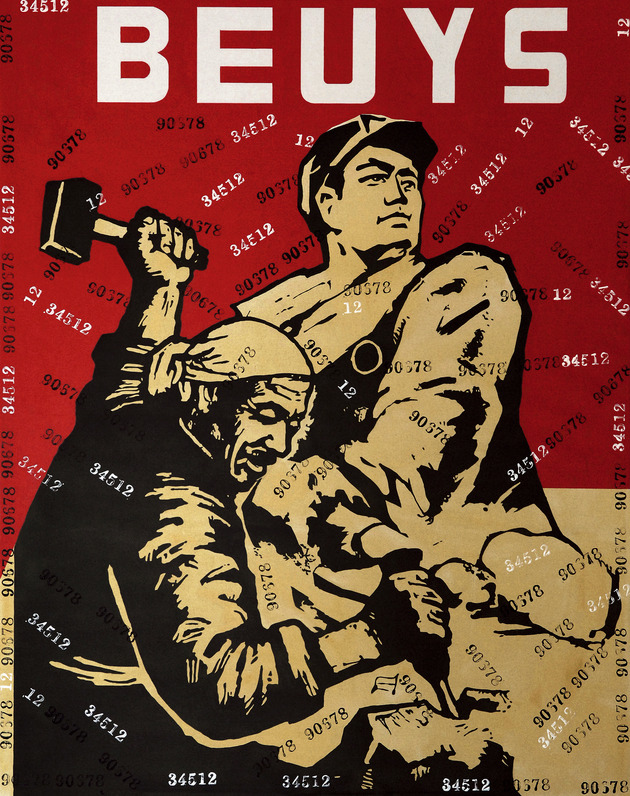

The first time I ever saw a Beuys was in an imported magazine that included illustrations of some of his works. Of course, I could not understand the text because it was in a foreign language, but the pictures were genuinely alluring; to me they seemed less like works of art than like works of what I call “alchemy.”

Appreciating the works of Warhol and Beuys was challenging and puzzling; I was indeed bewildered. It was almost like reading Kant’s books, when often I found myself perplexed by words. But these were words that, despite being baffling, were also fascinating. In my pursuit of art, these two artists have influenced me greatly. To this day, they remain my favorite artists.

Beuys is what I call an “alchemist”; he is an artist who creates enigmas, as he has always created layers and layers of “mist.” For instance, in his performance piece How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, it isn’t particularly clear what ideas he is trying to bring to the table. “To explain art to a dead hare” is indeed a difficult task. And the degree of such difficulty is perhaps beyond Beuys’s own grasp. All this mystic sense that he presents in his works is what makes me so fond of him. At times it feels as if he is giving serious thought to certain questions, and yet all of these questions are somehow so detached from, or even devoid of, reality. He seems to be discussing art from a metaphysical standpoint. He practically puts himself in a position where neither truth nor falsehood can ever be proven.

As for Warhol, he makes the ordinary even more ordinary—he lives in the light of day. When people tried to discuss his art with him, they would ask, “Is this what you meant?” Then even to the most obvious or foolish questions, he would usually answer, “Yes, that is exactly what I meant.” There is a particularly famous interview with Warhol where, during the whole thing, he answered questions with either “Yes” or “No.” These were his only answers. In the end, all that the media could report about the art was what they inferred or interpreted from his one-word responses.

This is actually related to the essence of Warhol’s works, for he eliminated from them all traces of individuality or personality. You see them as by-products of industrialization, of mass production, and so on. This is exactly where his greatest contribution lies—in industrializing artworks. He chooses meaningless images, transmits these meaningless images in meaningless fashion, and convinces everyone that they are actually meaningful.

Danto Gave Warhol’s Works Their Transcendental Value

The German art critic Klaus Honnef once made a very accurate remark about Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys. He said that they are like “the palm and the back of a hand.” From what I see, Warhol’s work only reveals its true greatness when it is appreciated alongside Beuys’s work. The two exist on the same level; without Warhol, Beuys’s art loses its sense, and without Beuys, Warhol’s becomes boringly mundane.

If we look at Warhol and Warhol only, art would seem to be so lacking and superficial. But if we place Beuys next to Warhol, we see that contemporary art has its true aura. Beuys is concerned with politics and even involved himself in political activities, such as those of the German Green Party. But from my point of view, these are not important. What Beuys does is to use politics as a means of doing. From the same viewpoint, Warhol’s art is a means of removing the so-called aura of art.

Yet does this mean that Warhol’s works do not have an artistic aura? Not really. For instance, Warhol has a piece in which he used silkscreen printing to depict numerous pairs of high heels. High heels are are objects that are charged with highly subjective meanings; when you use them in your art, there is always something attached to them. This is the allure of the aura of contemporary art. You inevitably think of the aura, of its reason for being there and of all that is around it or beneath it; otherwise, how would you explain the high heels in the painting?

Perhaps Warhol wasn’t giving much thought to all of this when he created his works. After all, Warhol’s ideas for his works are based on industrialization. Most of today’s high heels are the products of mass production. Warhol’s silkscreen printing technique is also an industrial method. In fact, none of us can claim to genuinely know what Warhol’s true ideas were, but the person who bestowed the aura upon Warhol’s works was the philosopher and art historian Arthur C. Danto. In April 1964 Warhol exhibited Brillo boxes in the Stable Gallery on East 74th Street in Manhattan. Danto went and saw those works, and he was the one who gave Warhol’s art its transcendental value.

We all know that Warhol rarely ever answered questions directly and, of course, we may say that this is how some artists choose to represent themselves, that is, by letting others speak for them, letting others bestow meaning on their art. Thus, if it were not for Danto, who gave transcendental descriptions of those works, Andy Warhol would not be the Andy Warhol we know today.

The simplest and perhaps the most truthful explanation we can give of Pop art is that Pop artists take what is easily found in the everyday world and reinvent or represent it in a particular way. On the surface, this idea seems banal and commonplace. But if this were all there was to Pop art, then it would be meaningless and would have no artistic aura. So in this regard, we must thank Arthur Danto, because not only did he give Warhol his significance, he also gave Pop art its significance. Before Danto, many writers had critiqued and commented on Pop art, but no one had given it a sense of transcendence.

The Connection between the Great Criticism Series and Political Pop Art is a Matter of Historical and Political Circumstance

Whatever Beuys and I have or don’t have in common is pretty noticeable, and the differences between us can probably be explained by looking at Warhol. Warhol’s works are direct and clear; his art comes to us easily—what he shows us is exactly what we see. But this is also the problem with his art: it seems superficial. However, when I try to look beneath this superficiality—while I cannot say I see something deep and profound, I can certainly vouch for the existence of some kind of wisdom.

Warhol’s aesthetic lies in the “beauty” of the ordinary, in the “beauty” of the mass culture. His works are actually technically very artful, well executed, smooth, and abundantly layered. Yet given the conditions at the time—a time when Expressionism and abstraction were dominant, a time when peculiar brushstrokes and bizarre materials were fashionable—Warhol’s values were apparently considered counter to the mainstream. His aesthetics arose from the mass culture, but in my view, this is different than if they had arisen from the people.

The concept of “the people” is a political concept, one that under most circumstances refers to the lower class and is associated with industriousness, hardship, and dedication. The concept of “the masses,” on the other hand, seems to me to be more related to the idea of “citizens”—of people in a society who are more concerned with materialism, consumption, and pleasure. My art refers to the concept of “the people,” and not “the masses.” This is the understanding I bring to Political Pop art.

Li Xianting was the first person to connect my Great Criticism Series with Political Pop art.6The term “Political Pop art” was coined by art critic Li Xianting in 1992. It refers to a trend begun in 1987 of depicting influential political figures and major political events in China in a satirical manner. According to Li, certain paintings by Yu Youhan, Zhang Peili, and Wang Guangyi, fall into this category. Political Pop artists considered Andy Warhol to be an important reference for their aesthetic language. [YL] Back then I was working on the idea of using newspapers published during the Cultural Revolution7The Cultural Revolution, also known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, began in 1966. Mao Zedong, the chairman of the ruling Communist Party, was being threatened with insubordination by fellow politicians. As a means to secure his position, Mao encouraged all citizens to confront their superiors and usurp their power. Thus he unleashed the Cultural Revolution, using the newly empowered citizens to overthrow his political enemies. The movement was meant to have a profound impact mostly on culture and morals but it eventually affected the country’s social structure and economy as well. [LD] in my work but hadn’t yet figured out the details. Later on, Zhang Peili gave me a book about newspapers from the time of the Cultural Revolution, which eventually helped to launch the Great Criticism Series.

In the collection Zhang gave me, I found campaign posters addressed to workers, peasants, and soldiers.8During the Cultural Revolution all people in subordinate positions were called to engage in “great debates” with their superiors, with the aim of challenging and discrediting them. Such confrontations were encouraged within family hierarchies (sons vs. fathers) as well as professional ones (workers vs. employers). Workers, students, peasants, and soldiers, collectively called “gong nong bing” (literally, “workers, peasants, soldiers”), were those mainly addressed by these huge campaigns, which greatly advanced Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The campaign posters were very popular and could be seen everywhere at the time. [LD] I used a grid to enlarge and transfer those pictures onto canvas because I wanted to retain the rudimentary, clumsy feeling of the original images. I incidentally included a Coca-Cola logo in a painting and I found it interesting, and so I kept it. This is how I came to create the first piece in my Great Criticism Series, Great Criticism: Coca-Cola.

In the latter half of 1990, I took photos of the five works in my Great Criticism Series and sent them to Li Xianting. Old Li responded by letter and noted the connection between my works and Political Pop art. His remarks were justified back then, given the historical and political situation. Nonetheless, if nowadays the media still sees me as nothing but a Political Pop artist, then they will have overlooked some even more important things.

In Warhol, I See What Society Expects of Me

Frankly speaking, Andy Warhol and I are very different because we come from different backgrounds. In Warhol’s works, you see great quantities of Western, commercialized objects. In my art, you will not find images that have been produced through the manipulation of photographs or advertisements; I build my art via the strength of “the people.”

Western logos are complex to me because they carry a sense of fetishism. In the Great Criticism Series, I tried my best to maintain a neutral stance in presenting the two ways in which I believe human beings operate. One reflects a utopian attitude, the other a fetishistic leaning. I placed both of these things into the same frame. The combination of these two disparate tendencies is one of the things that draws peoples’ attention to the Great Criticism Series.

Comparatively speaking, Andy Warhol’s works are simple, and mine are complex. More often than not, simplicity outshines complexity. Warhol impels the masses to give meaning to meaningless images. Even in response to the silliest or most naïve questions, his response is always, “Yes, that is exactly what I meant.”

But I am different from Warhol. My education and background prevent me from being as extremely simple as Warhol can be. So, when it comes to ideas and concepts, Beuys has a greater influence over me, which is why, when I try to explain my own works, I am more willing to use ambiguous words to interpret them. In me you will see some very complicated, unorthodox things, especially when it comes to ideas—I enjoy a way of thinking that allows for uncertainty, obscurity, ambiguity, and even a twisting of the facts. After all, Conceptual art has ambiguous boundaries, just like ideas—things we cannot touch and cannot see—do when we speak of them.

As for Andy Warhol, his influence on me is mainly in how I see myself when it comes to what society expects of me. On a deeper level, I admire Beuys’s work, but as an artist who bears societal self-expectations, I also relate closely to Warhol. From a popular view, people might be more easily attracted to Warhol’s work because its outward appearance is very worldly and easily understood—even though we might not know what it actually means.

For the original Chinese text, see The Beijing News, October 9, 2013.

The text is translated from the Chinese by Lina Dann and annotated by Yu-Chieh Li and Lina Dann. All images have been added by post editors.

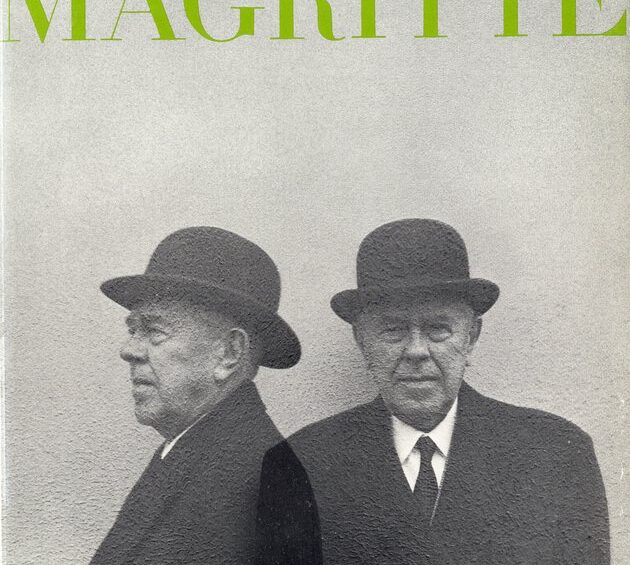

My Soul Mate Magritte

By Zhang Xiaogang 张晓刚

Publication: 《艺术世界》[Art World]: no. 5 (2001): 72–73.

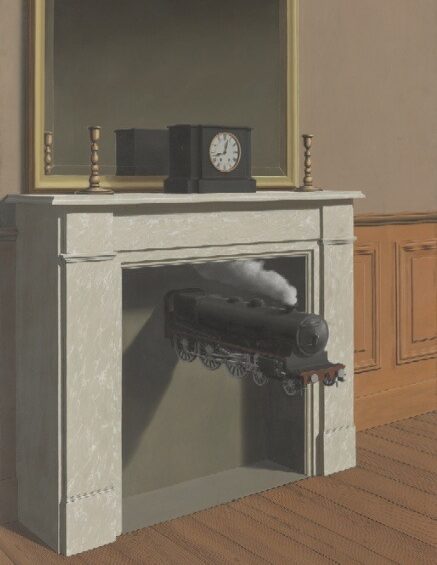

Language: Chinese

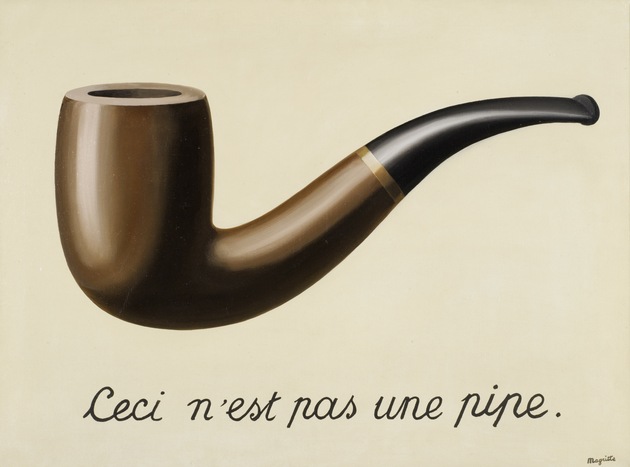

The first time I learned of René Magritte was a little after I started painting. My mentor had lent me a copy of The History of Modern Western Art, hoping that I would “sharpen my artistic perception.” It was one of those archaic books printed before Liberation,9The period known as the War of Liberation was part of the Chinese Revolution that took place between 1946 and 1950. (LD) with Traditional Chinese characters, vertical typesetting, and black-and-white illustrations, on old yellowed pages that were flipped from right to left.10Traditionally, Mandarin Chinese books are written vertically, with their characters running from top to bottom in rows proceeding from right to left, so that the book pages are numbered from right to left as well. After the War of Liberation, the Communist victors established Simplified Chinese characters, replacing the more complicated Traditional Chinese characters. Partly owing to Western influences, books could also be printed with lines running horizontally and pages running from left to right. (LD) I seem to recall that it started out by introducing French Realists like Gustave Courbet and François Millet, and ended abruptly with the Surrealists and Dadaists on the last few pages. To a seventeen-year-old youngster first entering the world of painting, they [the works of the Surrealists and Dadaists] were certainly puzzling and not easy to appreciate—and much less enticing than the work of Peredvizhniki [Russian Realist painters] like Ilya Repin and Vasily Surikov. I asked my teacher, “Why do modernists portray people in such an ugly way?” The teacher said, “Forget about them; they are simply a bunch of idle people. Now go and work on your still-life paintings!” Nonetheless, a few big names stuck in my head, and one of them was this “humorous” Magritte—perhaps because he drew a pipe and wrote on it, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe [see fig. 1]). What does that even mean? This question bothered me for more than a decade.

As I graduated from college and continued sharpening “my artistic perception,” I found myself growing fonder and fonder of Surrealism, and even mimicking Surrealist artworks and thriving on it during the ’85 New Wave.11The term “’85 New Wave” was coined by Gao Minglu in 1986 to periodize a trend of organizing art collectives, art symposia, and exhibitions in China, especially between 1985 and 1986. (YL) Magritte has since become one of the greatest masters I admire to this day.

Like many of my fellow artists, I started studying art through printed works. This means that when you come across a masterpiece that is poorly printed, not only must you rely on reading and studying related information to understand the background from which the artwork emerged, but also you must develop a good sense of imagination in order to picture the original piece of art. For instance, when I read Van Gogh’s biography12Here it refers to the Chinese translation of Irving Stone’s Lust for Life, which was avidly read by Chinese art students in the 1980s. (YL) back then, I completely believed that this Dutch painter, who spontaneously started a painting career, was an amateur who basically just randomly stirred the yellow paint with the blue and threw it onto the canvas, and then left and walked to a cheap bar where he would have melodramatic affairs with prostitutes—and this is, indeed, the story of a “genius’s tragedy” that has stirred the lives of so many young Chinese artists stepping into art. It wasn’t until one day, when Armand Hammer, who was in the oil business, brought his art collection to China for a museum exhibition,13This refers to the exhibition 500 Years of Important Works Collected by Armand Hammer held at the National Art Museum of China, Beijing, from March to May, 1982. One hundred and nine oil paintings and drawings were included in the show. (YL) and I saw paintings that Van Gogh had done during his time in a mental hospital, that I realized the story that I had believed in was completely fallacious. Van Gogh certainly mastered the layering of colors, creating melodious lines on canvas, and so much more. What words can do to art when it comes to distortion and exaggeration can sometimes be truly cruel. To prove the existence of that fine line between genius and insanity, I later paid a visit to the Van Gogh Museum in the Netherlands. When I came out and sat on the stone steps in front of the museum, I was overwhelmed by great awe and gratification. I need not elaborate on the awe, but the gratification was mixed with a sense of relief: I finally saw that I need not belong with those artists who paint on the edge of borders—this approach to art led many Chinese artists to possess a seemingly rich background knowledge of the literature of art, but at the same time to misread or misinterpret it and, interestingly, to form thoughts or appreciations of their own. This is why some say today that the reason why Chinese contemporary art is drawing international attention is because it is relatively closed and self-contained. And yet, while all this apparent energy that comes from being closed might shine now, how long can it last? It’s truly doubtful that it will.

Back to Magritte. Similarly, all those legends or rumors about him (including his fondness for painting on restroom doors, going alone to detective movies, or playing chess with random elders on the street) had me imagine how he handled the oil paints with great delicacy, how he made good use of his solid sketching technique and layered until thickness and firmness were reached.

In early 1992, I finally had a chance to travel to Europe,14In June 1992, Zhang departed for Europe to be a visiting scholar at the Kunsthochschule in Kassel, Germany. He visited major museums in Germany, the Netherlands, and France, and returned to China in October of that same year. (YL) and when I was faced with Magritte’s original works, firsthand for the first time, including those that I had and hadn’t seen before, I thought to myself, “I can’t believe painting could be done this way!” He had reduced his colors, shapes, and even painting techniques to the least possible, almost as if he “couldn’t paint.” It is thus fair to say that his accomplishment in surpassing traditional art is, in my opinion, beyond what any of his contemporaries had ever achieved. Using a painting language that is simple, subtle, and plain, he rearranges different scenes and objects, placing them in a set-up space, creating a certain sense of dislocation and illusion. Through the painting, we are brought to this dreamlike space of thoughts, where we ponder the art’s multiple meanings and multifaceted spirituality. No wonder he wrote on his painting, “This is not a pipe!”—or better, “This is not merely a pipe!”

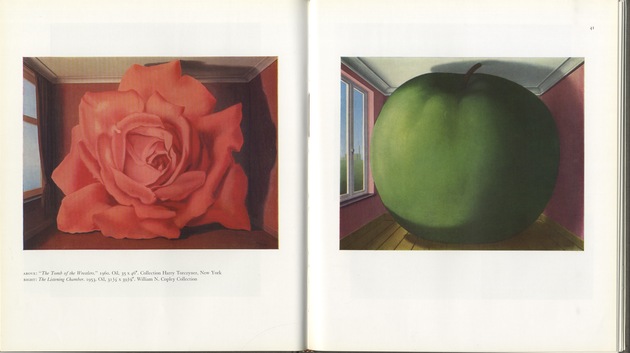

He magnifies a bouquet of pink flowers or a green apple and places it in a narrow space (see figs. 2 and 4); sends a roaring train running out from the fireplace (see fig. 5). Magritte even depicts humans as objects, bringing forth a peculiar change in the relationship between humans and reality—humans are no longer users of a space, but instead objects that shares the illusional, set-up space we see with so many other objects. With this manipulation, it is hard not to stir up sensations within the heart of the viewer. It is not hard to imagine that, in an epoch like Magritte’s, artists like himself, who used unusual approaches to challenge what was established in tradition and explored the connection between art, psychology, and philosophy through visual arts, must have faced harsh critiques. Meanwhile, they have brought the history of visual arts into a whole new page, and had a deep impact on up-and-coming artists (including most Chinese artists).

Cool but irrational, imaginative but restrained, realistic and terrifying but at the same time alienating, using visible objects to bring thoughts into an invisible tunnel, depicting an indescribable, mysterious philosophy and pessimistic humor—this charisma of Magritte’s has enchanted me all these years. It has also become the standard to which I hold my art and the state that I hope I will some day achieve. In all these years, something Magritte once said has had unexpected impact on my mentality: “If the spectator finds that my paintings are a kind of defiance of ‘common sense,’ he realizes something obvious. I want nevertheless to add that for me the world is a defiance of common sense.”

I think that in an artist’s path of growth, over and over again, he encounters a master with whom he becomes infatuated but must later bid painful good-bye to, as he moves on to encounter other forerunners with whom to connect and communicate. On this never-ending path of recognition and substantiation, those who eventually become “soul mates” turn up rarely, and even more so down the road. Magritte and Italy’s de Chirico are alike in that both their magic realism was of great influence and inspiration to me. It was through them that I learned how to “keep a distance” when examining our heavy history or facing our ever-changing reality. Meanwhile, I strive to depict our lives through an internalized language, to mind those souls that are so often neglected, and to create a “Kingdom of Illusion,” where our souls can rest within—if only temporarily.

Note: For the original Chinese text, see《艺术世界》[Art World]: no. 5 (2001): 72–73; He Xiangning Art Museum, ed., Image is Power (Hunan: Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, 2002) p. 269 [in Chinese].

The text is translated from the Chinese by Lina Dann, annotated by Yu-Chieh Li and Lina Dann. All images are added by post editors.

[Chinese version follows]

我的知己——马格利特

By Zhang Xiaogang 张晓刚

Publication: 《艺术世界》: no. 5 (2001): 72–73.

Language: 中文

第一次知道马格利特是在刚刚开始学画不久,我的启蒙教师为了让我“增加艺术修养”,特地借给我一本解放前出版的《西方现代艺术史》,竖排版、繁体字、发黄的纸张、黑白插图、从右翻到左的那种老书。记得好像是从法国现实主义的库尔贝、米勒开始谈起,到了最后几页迅速地以超现实主义,达达主义结束。对一个初学画画的十七岁青年来说,自然是看得云里雾里的,远不如俄罗斯巡回画派的列宾、苏里柯夫来得激动。去问老师,那些现代派为什么要把人画得如此丑陋?老师说,别管他们,他们是一群颓废的人。你现在好好地画静物去吧!尽管如此,但是当时却无意中记住了几位大师的名字,其中之一便有这位“爱开玩笑的”马格利特——可能是他画了一个烟斗,而且写上“这不是烟斗” (图1) 那是什么呢?这个问题困惑了我起码十年。

随着大学毕业,逐步增长的“艺术休养”,开始对超现实主义从接触到发自内心的喜爱,直至以模仿超现实主义风格的作品在85新潮中混迹江湖,马格利特成为了我至今仍非常崇仰的大师之一。

我和许多同行一样,都是从印刷品开始学习艺术的,这意味着当你面对一张印刷得很差的大师作品时,除了通过阅读相关的知识去理解那些杰作产生的背景之外,还得对作品的原貌有充分的想象力。比如当时看《凡高传》,完全相信了这个半途出家的荷兰画家,基本上就是把黄颜色和蓝颜色胡乱搅拌之后甩到画布上,然后就去小酒馆喝劣质的酒、对妓女滥发真情——这便是搅乱了多少初学艺术的中国青年艺术家生活的“天才的悲剧”。直至有一天,卖石油的哈默老先生把自己的艺术藏品拿到中国美术馆来展出,当我看到凡高在疯人院里画的油画时,才发现原本不是那么一回事。凡高实际上非常懂得如何一层一层上颜色,懂得如何经营线条在画布上的旋律感等等。可见文字对艺术的某种过分地渲染和曲解,有时真够残酷的。为了证明天才和疯狂的分界线,后来我还专门去荷兰参拜了凡高博物馆,看完出来之后,坐在博物馆门前的石台阶上,心里真是说不出的崇敬和庆幸——崇敬自不必多说,庆幸的是自己终于发现我不属于这类需要在临界边缘作画的画家——这种学习艺术的结果,曾使许多中国艺术家对西方艺术除了对其文本的背景有深刻的认识外,同时也因为这种种的误读反而在其中摸索出自己的感觉。所以有人会说,中国当代艺术之所以在今天能够引起国际上的关注,其中一个原因恰恰是因为相对封闭的结果。当然,这种由于闭塞而产生的某种程度的鲜活力,究竟能维持多久,值得怀疑。

回到马格利特来。同样面对他的种种传说(诸如他喜欢在卫生间的门口作画;喜欢一个人去看侦探电影;喜欢和街上的老头下棋等等),同样地开始想象他的油画色彩处理得如何如何微妙,他如何运用“坚实的素描基础”,通过反复地描绘达到造型的厚度感和坚实感等等。

直到1992年初,终于有了一次去欧洲的机会,第一次面对大量的见过和没见过的马格利特原作,才发现原来还可以“这样画画的”!他把色彩、造型,以至描绘手段都降低到几乎“不会画画”的地步了。换句话说,他对传统艺术的超越,我认为远远超过了他的同时代的画家。平涂,简洁而又含蓄的绘画语言,将现实中的各种场景、物体重新组合,置放在一个虚设的空间之中,产生出某种心理上的特定的错位感和虚幻感。从而使人通过绘画进入一个梦境般的思维空间,再回头面对视觉艺术的多重含义和多角度的精神指向。如次种种,都曾使我在惊诧之后敬佩不已。难怪他要在画布上写上“这不是烟斗!”或者“这不仅仅

他可以把一束粉红色的鲜花,或者一个绿色的苹果放大,置放于一个狭小的空间之中 (图2, 4); 将一列火车从壁炉中呼啸着开了出来 (图5) 。马格利特甚至将人作为某种物体来进行描述,使人与现实的关系由此发生了奇异的变化——人不再是一个空间的使用者,它与其他物体共同分享了我们所见到的那个迷幻的虚设空间。这样的处理方式,使人看后难免不为之心理上产生某种异样的悸动。可以想象,在那个时代,像他们这样的艺术家,用如此怪诞的手段去挑战传统的习惯,通过视觉艺术的方式,探索艺术与心理学、哲学的关系,一定引来许多莫名的诽议,同时,也将视觉艺术史带入了一个崭新的艺术领域,对下一代艺术家(包括大部分的中国艺术家)产生了深远的影响。

冷静而又非理性;充满幻想而又保持住应有的节制;真实恐怖却又令人感到陌生;利用可见的物体,使人的思维跨入不可见的隐秘隧道,呈现出某种神秘的哲理和灰色的幽默——马格利特的这种魅力使我长久的着迷。同时也成为我长期以来对自己艺术的某种价值判断和境界追求。许多年来,马格利特说过的一句话,始终在我的潜意识中起着意想不到的作用:“如果观赏者发现我的绘画是一种对‘平常感觉’的挑战,他就意识到了某种特殊的东西。然而,我要说明,在我看来,这个世界就是对平常感觉的挑战。” 我想,一个艺术家在他的成长过程中,总是不断的要与一些曾经迷恋的大师忍痛告别,然后又重新的认识另外一些与之沟通的前辈。在这条不断认知不断验证自己的道路上,最后能成为“知己”的,发现已越来越少。马格利特与意大利的德·契里柯一样,他们的“魔幻现实主义”作品,始终对我产生着深远的影响和启迪。正是通过他们,使我学会了如何“有距离”地去体验我们的深重的历史,以及我们所面临的多变的现实。与此同时,通过使用“内心化”的语言方式去描述我们的生活,去关注那些常常被忽略的心灵,去营造一个使我们的灵魂能够得以暂且栖身的“虚幻王国”。

October 18, Xiaogang’s Letter to Lü Peng

By Zhang Xiaogang 张晓刚 1990, first published in 2010

Publication: Amnesia and Memory—Zhang Xiaogang Letters (1981–1996)

Publisher: Peking University Press

Language: Chinese

Hello, Lü Peng!15Lü Peng (1956–) is an art historian and professor at China Academy of Art in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province. (YL)

I apologize for taking so long to gather the slides and for sending them out to you only today. After I returned to Huangjueping16Huangjueping is a district in Chongqing City, Sichuan Province. (LD) from Chengdu,17Chengdu City, Sichuan Province. (LD) I kept up my good spirits from Chengdu and made another five oil paintings, again in black and white (see figs. 1–5). I used undiluted and unblended paints, laying them on the canvas with painting knives; on the canvas I created a collage of cloths of different textures and colors (black, red, brown), but the overall figures were more squared than what I did in Chengdu, each resembling a cagelike frame. The heads that smile and ponder live freely in the painting; they are human heads and faces, or wolf heads and lamb heads. Grinning, with their ice-brick teeth. But make no mistake—they are not making faces that express emotions to the world (like Expressionist works). Surely my works do carry a hint of Expressionism, like those demons I painted in 1984, but I know in my heart that I disdain Expressionism and don’t belong in Realism. After finishing the fifth painting, I forced myself to stop and undergo some cleansing. On reviewing the history of Western art and observing contemporary Expressionists domestic and foreign, I once again found myself most fond of artists like El Greco, Hieronymous Bosch, Giorgio de Chirico, James Ensor, René Magritte, and others along this line, like Alberto Giacometti, Francis Bacon, Balthasar Klossowski, who all belong in the same class. And, of course, there is Odilon Redon. Of all the Neo-Expressionists, Germany’s Anselm Kiefer and Italy’s Mimmo Paladino are my favorites. I think what I am trying to express in my art is a concern for the state of our existence as human beings in the modern world (that is, expressing a certain fear of death and the genuine experience of exploring what lies beneath the appearances of things) and our spiritual journeys as well as intuitions concerning life and death. It is a gloomy passage holding both life and death, heading between reality and illusion. Both the realistic (such as early Expressionism and Pop art) and the purely “illusional” (such as the “reverie” explicitly created by Dalí) seem inaccessibly alien to me. There’s simply no affinity between purely rational material and me, or Conceptual art or abstract art and me. As Max Beckmann once proclaimed, “That is hidden behind so-called reality. . . .To make the invisible visible through reality.”18Zhang quoted from a Chinese translation that is fragmentary. The original text by Beckmann is “Es handelt sich für mich immer wieder darum, die Magie der Realität zu erfassen und diese Realität in Malerei zu übersetzen—Das Unsichtbare sichtbar machen durch die Realität. (My aim is always to get hold of the magic of reality and to transfer this reality in painting—to make the invisible visible through reality.)” Max Beckmann, in Schriften und Gespräche 1911 bis 1950 (München: Piper, 1990) p. 49. (YL) Kabbalah’s occultism and China’s Zen also explore this path. De Chirico and Magritte are especially worth noting; de Chirico’s dusky streets contain gloomy, mysterious, long shadows that divide time and space into halves, where the defining lines of ancient monuments and sculptures or human characters are blurred, and we vividly feel the intense power of the reality that is hidden beneath. As for Magritte, to classify him as a Surrealist would be a superficial judgment. His painting The Listening Chamber is beyond what Dalí can achieve or embrace. And Bacon, a fine artist who captures reality through illusion, if looked at closely, reveals how different he is from the Expressionists.

China’s modern art, especially after the May Fourth Movement19May Fourth Movement was part of an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement in China at the beginning of the twentieth century. A student demonstration protesting the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles took place in Beijing on May 4, 1919. (LD) and Lu Xun’s20Lu Xun (1881–1936), novelist, editor, translator, literary critic, essayist, and poet, was a leading figure in modern Chinese literature. He was especially influential during the May Fourth Movement in China. (LD) advocacy of “Art for life’s sake” (not to mention Mao Zedong’s Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art in 1942), has been wavering between being “instrumental” and “recreational.” The New Wave Movement accomplished its mission of destruction, and afterward along came the motif of rebellion in the so-called New Academic Art and New Ink Painting Movement—a sense of escape from the feudal literati. The materialism in Shanghai, Wang Guangyi’s rational spirit and cultural introspection, all these might seem frigid, but unlike the two “new,” corrupt literati, at least they strive to explore and bring art to a deeper level with a constructive spirit. Rational art isn’t threatened by the dilemma between traditional culture and social reality. If not for its constructive spirit, it might have been at risk of reducing itself to an instrument or a hobby. Sichuan artists love to talk about “feelings,” but I feel that we should elevate that to “sensitivity.” The other day we were all wisecracking together, and I joked that if the southwestern artists continued “feeling” their way, eventually they won’t make their way in “history” and they won’t make it in the “economy” either, ultimately becoming just some “neither-nor community.” And this is what essentially constitutes the lower part of the pyramid—a bunch of recreational artists. But then again, the concept of a pyramid might not suit modern society anymore. In the recent American market, Russia’s long-suppressed avant-garde art and Latin America’s regionally colored art have been very well received; perhaps China’s art will one day travel the same path? To make use of its unique political circumstances or to make use of regional features and express them in an international language in hopes of earning international recognition? Well, this is unless China undergoes an earth-shattering revolution in the next decade or so and builds a whole new picture, like what Spain has been doing. Lü Peng, frankly speaking, at times I think of these “big issues” and my heart is overwhelmed with emptiness. Leaving my country to pursue art abroad was a path I had to resort to—but a desolate one. That being said, what needs to be done has to be done, otherwise all could have been worse.

Zou sent me a copy of The Artist, and I went through the pieces Yi Dan and you wrote on Damao.21Nickname of the artist Mao Xuhui (1956–). (YL) I honestly think they are some of the best reviews The Artist has published in a while; I wonder how Damao feels about them. Too bad the reproductions from his slides are awful.

Anyway, these are some thoughts I have had in my mind in the past few months, and I have elaborated a great deal, and so forgive me if they are somewhat unpolished; I hope I’m not making a fool of myself before a critic. How have you been lately? When will the first issue of Art Market be published? Chengdu might be a decayed city, but it sure is so much better than this dreary Huangjueping. I wish I didn’t have to stay!

Give my regards to Xaiohu and Lu Jing!

Xiaogang, October 18, 1990

Note: read the original Chinese text here. This translation is based on the letter published (in Chinese) in Lü Peng, ed., Amnesia and Memory—Zhang Xiaogang Letters (1981–1996) (Beijing: Peking University Press: 2010), pp.158–161.

The text is translated from the Chinese by Lina Dann, annotated by Yu-Chieh Li and Lina Dann. All images are added by post editors.

[Chinese version follows]

10月18日张晓刚致吕澎的信

By Zhang Xiaogang 张晓刚 1990, 2010 出版

Publication: 《失忆与记忆:张晓刚书信集》

Publisher: 北京大学出版社

Language: 中文

请原谅直到今天才把反转片整理出来给你寄去。从成都回到黄桷坪后,我又接着成都的那口气, 画了五幅油画 (图1-5), 仍是以黑白为主。将未经稀释和调和的厚颜料用画刀堆砌在画布上, 画面上也仍是用几种不同质地和色彩 (黑、红、褐) 的布拼贴, 只是整个的图形比之在成都画的更呈方形, 犹如一个个牢笼般的框架。 那些在微笑和沉思的头颅在其中自在地生存着,它们或是人形的头颅、脸面,或是狼、羊形的头颅。龇着冰砖般的牙齿。但是它们并非在做着某种表情面向人们展示某种情绪 (如表现主义的作品那样)。的确,我的作品也许有了某种表现主义的倾向,就像我1984年画的那些魔鬼,但我知道我是不属于表现主义的,更非现实主义的。画完第五幅之后,我强迫自己停下来,进行一番清理。 纵向地翻阅西方艺术史和横向地观察国内外的表现主义画家们,我再次发现自己喜欢的艺术家,仍然是像格列科、布什、契里柯、恩索、马格丽特,这条线下来的人物,如贾克梅蒂、培根、巴尔丢斯也属此类。当然,还有雷东。新表现主义画家群中,德国的基弗尔,意大利的帕纳迪诺是我最喜爱的。可以说,我所试图通过艺术来表达的是一种我对当代人的存在状态的关注(简而言之,表达某种对死亡的恐惧和对事物表面之下的内部真实的体验) ,以及对生命与死亡的心灵体验和感应。这是一条通往现实与幻觉之间,包容着生与死的幽暗通道。不论是现实的 (如早期表现主义,波普艺术) 还是纯“幻觉”的(如达利所刻意制造的“梦幻”)都给我一种堵塞的陌生感。纯理性的材料,概念艺术,包括抽象艺术与我更是无缘。如贝克曼所言: “表现在所谓的现实背后隐藏的东西。从‘可见的’通向‘不可见的’。卡伯莱神秘哲学和中国的禅宗正是这条道上的发掘者。尤其值得一提的是契里柯和玛格丽特,契的昏暗街道上那忧郁而神秘的长长黑影,把时空分裂成了两半,在那里,古建筑及雕像与人物的基本定义模糊了,使人震颤地惑受到那内部的真实世界的强大力量。而把马格丽特归为超现实主义不免显得表面,其《收听室》远非达利能企及包容的。还有培根,一位极好地通过幻觉的形式把握现实的优秀画冢,仔细对比,即可看出他与表现主义画家的极大差异。

中国现代艺术,自“五四”之后特别是鲁迅提出“为人生而艺术” (当然 《讲话》就更不用说了) ,就总是在工具与游戏之间徘徊,新潮艺术完成了破坏的使命後,跟着就要出现那些什么“新学院派”,“新文人画”的逆反心理——封建士大夫的逃避意识。上海的纯物质、王广义等的理性精神、文化反思,虽然觉得冷漠,但较之两个“新”的堕落文人来说,毕竟是一种把艺术向纵深发展的建构精神,而非理性艺术也同样面临着传统文化和社会现实的巨大压力,如果不具备建构精神,也有沦为工具和游戏的危险。四川画家爱说的“感觉”一词,的确应当上升为“感性” 了。前几天,大家在一起吹牛,我开玩笑说,如果西南艺术家再这样“感觉”下去,就将成为既进人不了“历史”又进人不了“经济”的“两不如分子”。而这种人正是构成金宇塔最底层的大量游戏画家。 当然,金字塔的概念也许巳不适合今日之时代了。最近在美国市场,苏联被压抑多年的先峰派艺术和拉美充满地域特点的艺术同样走红,也许中国现代艺术将来的命运也会如此,以政治背景的特殊或者以用国际语言表达的地域特征来取得国际艺坛的青睐? 除非在这最后的十年里中国来个翻天覆地的大变化,另立一个山头起来,如目前西班牙所干的那样。吕澎,说实话,有时侯想到这些“大问题”,不由得一片虚无。出国求生存更是我等的凄凉之道。当然,话虽如此说,但还是得干活路,否则情况更糟。

好了, 提笔写了这么多,都是我近几个月来的一些断想,不免肤浅粗糙,还望理论家多多包涵,见笑了。你近来如何?《艺术.市场》何时开张?成都虽然腐朽,比起凄凉的黄桷坪来仍然好多了,我真不想再呆在这儿了。

代问小胡、吕静!

晓剛 1990年10月18日

— An English version of this text is available here as “October 18, Xiaogang’s Letter to Lü Peng.”

- 1This quotation is difficult to trace without the artist’s help. After the Cultural Revolution, Chinese students became avid readers of works of Western philosophy and literature translated into Chinese. The Chinese editions were carefully screened by the government and often contained imprecise or incomplete bibliographical references to their sources. The fact that few copies of these translations are in circulation today adds to the challenge of identifying the editions on which they are based. Huang Yong Ping noted in his notes that he read Shu Weiguang’s book about Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy in 1982, a biography of Wittgenstein in the mid-1980s. Read more (in English) about the “reading fever” of the 1980s in interviews conducted by the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong: http://www.china1980s.org/en/interview.aspx (YL)

- 2The page numbers cited in this article refer to the Chinese edition of Pierre Cabanne’s Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971), which was originally published in French under the title Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (Paris: Editions Pierre Belfond, 1967). The Chinese version, issued by Art Publishing Co., Taiwan, in 1986, was translated from the English by Zhang Xinlong. All quotations from Cabanne’s book that appear in this article are translations of Huang Yong Ping’s citations from the Chinese edition. (Copies of the Chinese edition were available in the Guangdong region through Hong Kong. Dialogues was not the first source on Duchamp to enter China, but it was influential among artists, especially to those in the Xiamen Dada Group.) (YL)

- 3This numbered list contains a selection of the 384 instructions for artworks that Huang Yong Ping inscribed on the disk of his Big Roulette Wheel (1987). The artist developed them after reading Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and Pierre Cabanne’s Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. (YL)

- 4Possibly the book The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even; a Typographic Version by Richard Hamilton of Marcel Duchamp’s Green Box translated by George Heard Hamilton (London: 1960). (YL)

- 5When Huang was writing this article in 1988, he knew that he would participate in Magiciens de la terre at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1989. (YL)

- 6The term “Political Pop art” was coined by art critic Li Xianting in 1992. It refers to a trend begun in 1987 of depicting influential political figures and major political events in China in a satirical manner. According to Li, certain paintings by Yu Youhan, Zhang Peili, and Wang Guangyi, fall into this category. Political Pop artists considered Andy Warhol to be an important reference for their aesthetic language. [YL]

- 7The Cultural Revolution, also known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, began in 1966. Mao Zedong, the chairman of the ruling Communist Party, was being threatened with insubordination by fellow politicians. As a means to secure his position, Mao encouraged all citizens to confront their superiors and usurp their power. Thus he unleashed the Cultural Revolution, using the newly empowered citizens to overthrow his political enemies. The movement was meant to have a profound impact mostly on culture and morals but it eventually affected the country’s social structure and economy as well. [LD]

- 8During the Cultural Revolution all people in subordinate positions were called to engage in “great debates” with their superiors, with the aim of challenging and discrediting them. Such confrontations were encouraged within family hierarchies (sons vs. fathers) as well as professional ones (workers vs. employers). Workers, students, peasants, and soldiers, collectively called “gong nong bing” (literally, “workers, peasants, soldiers”), were those mainly addressed by these huge campaigns, which greatly advanced Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The campaign posters were very popular and could be seen everywhere at the time. [LD]

- 9The period known as the War of Liberation was part of the Chinese Revolution that took place between 1946 and 1950. (LD)

- 10Traditionally, Mandarin Chinese books are written vertically, with their characters running from top to bottom in rows proceeding from right to left, so that the book pages are numbered from right to left as well. After the War of Liberation, the Communist victors established Simplified Chinese characters, replacing the more complicated Traditional Chinese characters. Partly owing to Western influences, books could also be printed with lines running horizontally and pages running from left to right. (LD)

- 11The term “’85 New Wave” was coined by Gao Minglu in 1986 to periodize a trend of organizing art collectives, art symposia, and exhibitions in China, especially between 1985 and 1986. (YL)

- 12Here it refers to the Chinese translation of Irving Stone’s Lust for Life, which was avidly read by Chinese art students in the 1980s. (YL)

- 13This refers to the exhibition 500 Years of Important Works Collected by Armand Hammer held at the National Art Museum of China, Beijing, from March to May, 1982. One hundred and nine oil paintings and drawings were included in the show. (YL)

- 14In June 1992, Zhang departed for Europe to be a visiting scholar at the Kunsthochschule in Kassel, Germany. He visited major museums in Germany, the Netherlands, and France, and returned to China in October of that same year. (YL)

- 15Lü Peng (1956–) is an art historian and professor at China Academy of Art in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province. (YL)

- 16Huangjueping is a district in Chongqing City, Sichuan Province. (LD)

- 17Chengdu City, Sichuan Province. (LD)

- 18Zhang quoted from a Chinese translation that is fragmentary. The original text by Beckmann is “Es handelt sich für mich immer wieder darum, die Magie der Realität zu erfassen und diese Realität in Malerei zu übersetzen—Das Unsichtbare sichtbar machen durch die Realität. (My aim is always to get hold of the magic of reality and to transfer this reality in painting—to make the invisible visible through reality.)” Max Beckmann, in Schriften und Gespräche 1911 bis 1950 (München: Piper, 1990) p. 49. (YL)

- 19May Fourth Movement was part of an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement in China at the beginning of the twentieth century. A student demonstration protesting the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles took place in Beijing on May 4, 1919. (LD)

- 20Lu Xun (1881–1936), novelist, editor, translator, literary critic, essayist, and poet, was a leading figure in modern Chinese literature. He was especially influential during the May Fourth Movement in China. (LD)

- 21Nickname of the artist Mao Xuhui (1956–). (YL)