Luis Pérez-Oramas, MoMA curator and leader of the C-MAP Latin America group, discusses the challenges of collecting art from a region that complicates the art historical narratives by presenting a dynamic archipelago of modernities.

I would like to start this essay with a picture of the current Painting and Sculpture Galleries on the fourth floor of The Museum of Modern Art.

This is, I would say, an image of friction. In the first Gallery, there is a juxtaposition of works from (what according to MoMA’s narrative is) the second half of the 20th Century, featuring pieces made in New York during the early 1940s.

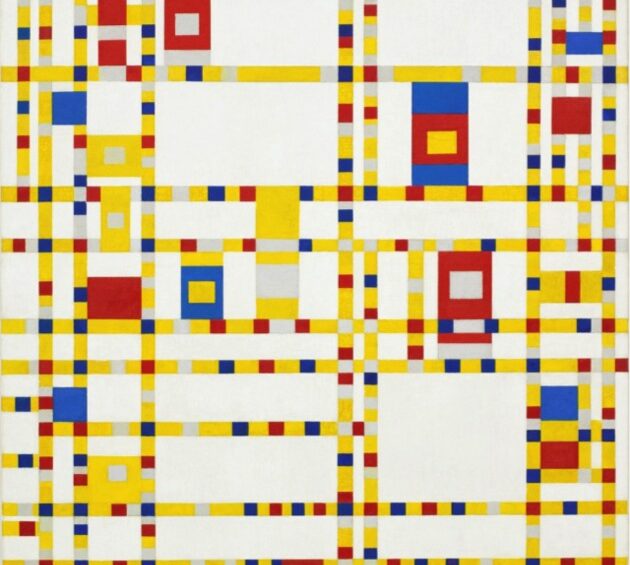

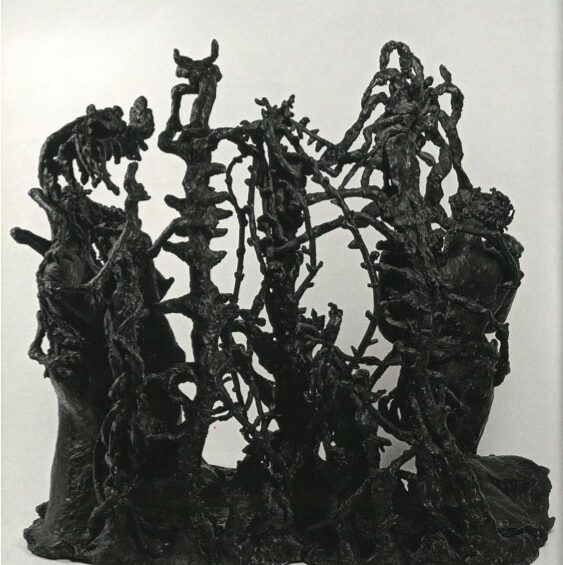

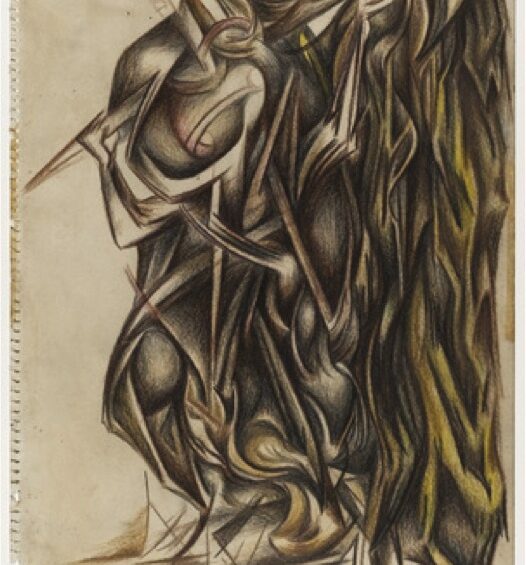

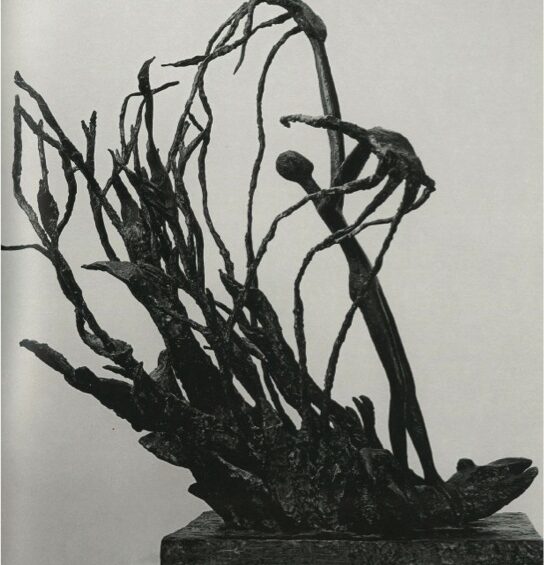

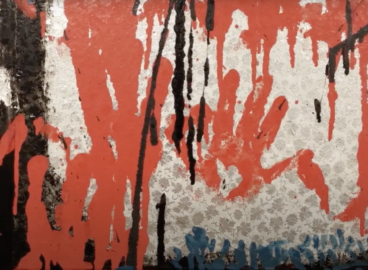

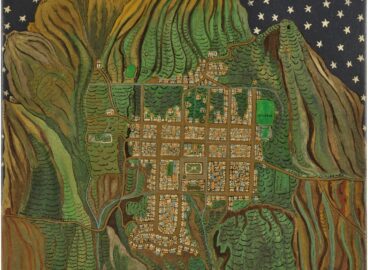

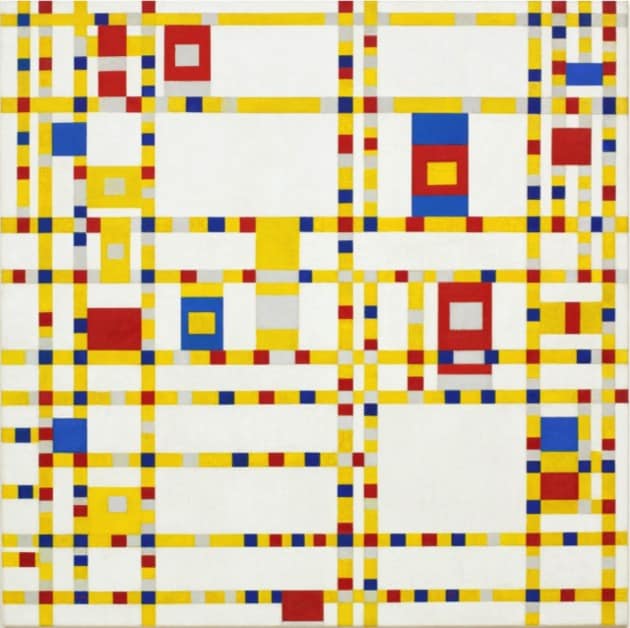

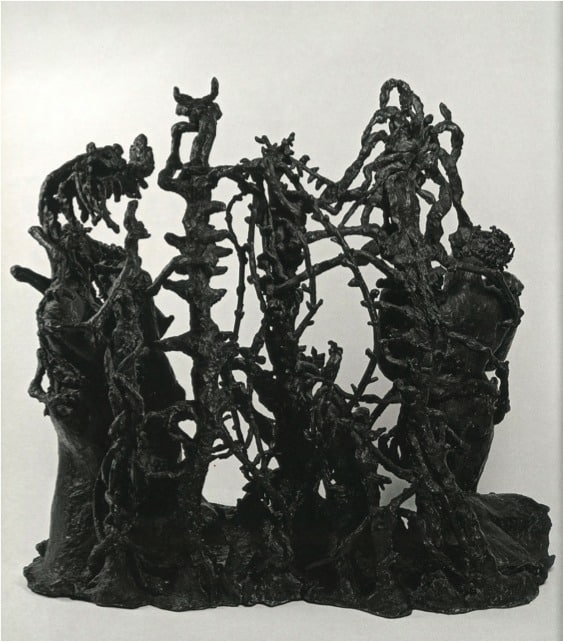

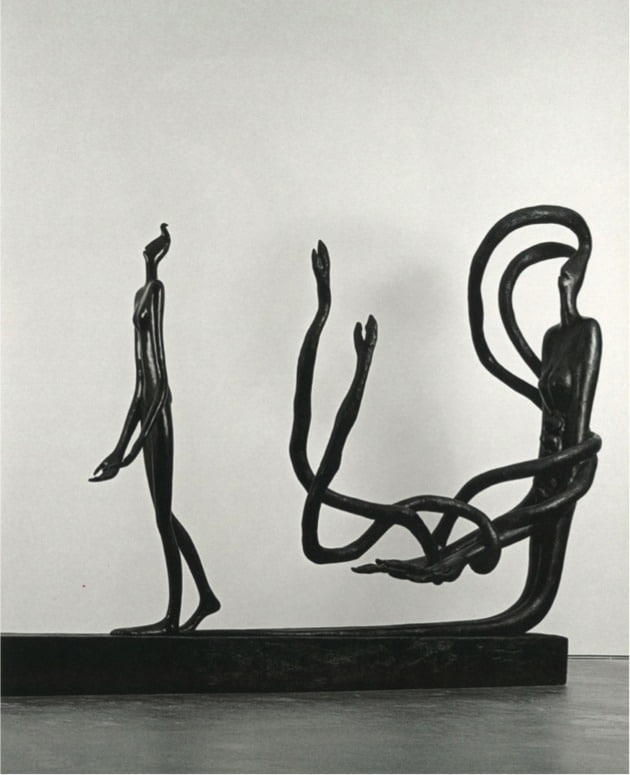

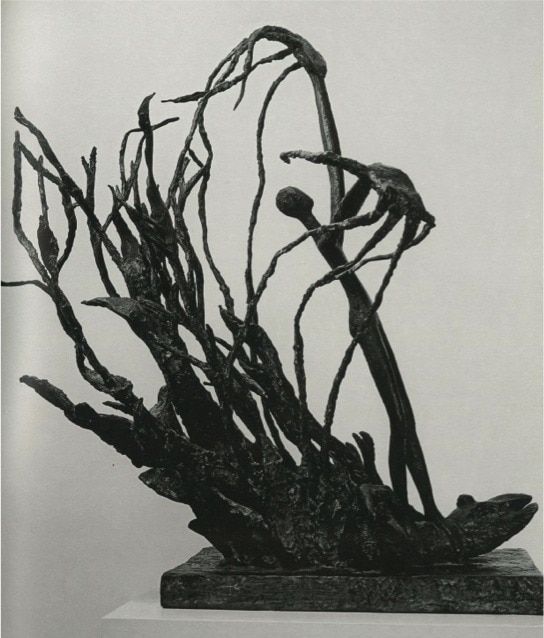

Against all stylistic odds, among these, one sees the work of two artists: The Impossible (1944) by Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins and Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942–43) by Piet Mondrian.

Although subject to radically different fortunes in terms of international critical reception of their work, and in spite of near-universal recognition of Mondrian as a landmark figure in modernist painting, the truth is that in New York in 1943, Martins was a much more successful artist than Mondrian.

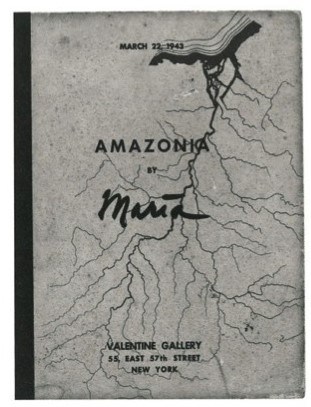

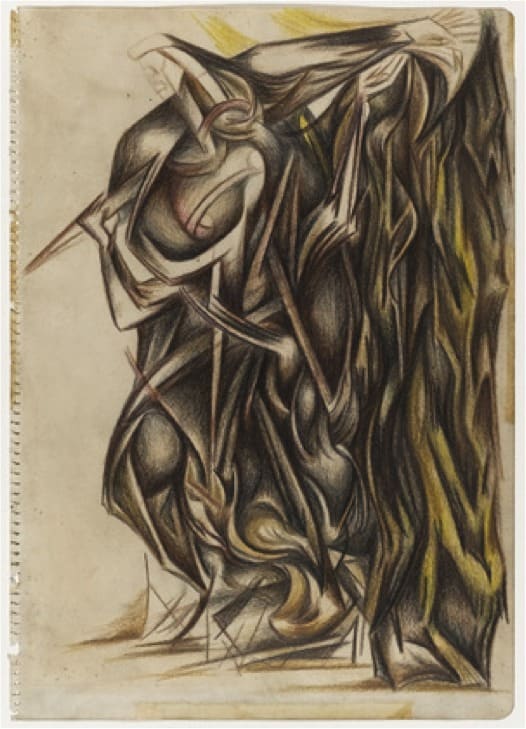

By then a neoromantic impulsion, materializing itself in a language of free gestures leading to a repertoire of Abstract Expressionist action painting, was trumpeting the New York art scene. It was during those days, in 1943, that Maria Martins showed her series of sculptures related to Amazonian myths in an exhibition at Valentine Gallery. Curiously, her work shared the gallery space with recent works by Piet Mondrian.

Martins sold all of her works from this exhibition, while Mondrian sold none of his. Yet Martins, a fascinating character and one of the most brilliant Brazilian artists of the 20th century, is today almost entirely forgotten. What isn’t generally known is that Maria Martins once owned Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie, one of the crown jewels in MoMA’s collection. Almost immediately after acquiring the painting, she donated it to the Museum, only to have her gift rejected—at least at first. The Museum of Modern Art initially turned down the gift, but then soon after, accepted and labeled it as “from an anonymous donor,” thanks to the effective diplomacy of Carlos Martins, Maria’s husband, who was the Brazilian ambassador in Washington and also a close friend of Nelson Rockefeller. One should not forget that 1943 was a time of war and that Brazilian rubber was more urgently needed than art. Hence, indirectly yet happily, the politics surrounding Brazilian rubber brought, with the generous help of a Brazilian artist—one who is today, unfairly, almost totally forgotten—and the belated blessing of Alfred Barr, the most brilliant painting ever painted by Piet Mondrian into the collection of The Museum of Modern Art. This anecdote may serve to fuel our reflections on the uncertainty of aesthetic and/or institutional judgment, on the politics of art (and, conversely, the art of politics), and especially on the ungraspable meanings of fortune and chance. I am less interested in the way Mondrian and his Broadway Boogie Woogie made their way into MoMA—which is basically the same way that Rubens made his way into the Prado, Leonardo into the Louvre, Velazquez into Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches—than in the friction that the odd juxtaposition of the work of the donor and the donated work create today when neighboring each another at MoMA (a juxtaposition that certainly ignores the ‘petite histoire’).

To what extent does the insertion of Maria Martins among the great figures of the New York art scene in the early 1940s modify and complement a narrative that is among the best established in the recent historiography of modern art?

To what extent does the unexpected presence of Mondrian among the constellation of artists who, at the dawn of Surrealism, were emphasizing the expression of irrepressible gestures and thus giving birth to Abstract Expressionism, serve as a token of the syncopated chronology and uncanny complexity that overwhelms art history time and again with the factual and often unaccounted evidence of singularities? Although looking at Maria Martins beside Piet Mondrian may not be much different than thinking about the Flemish peasant genius Pieter Bruegel the Elder painting Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind, a picture of blind people walking to nowhere, just after he had seen the then freshly finished Last Judgment by Michelangelo at the Sistine Chapel, the juxtaposition of Maria Martins and Piet Mondrian will serve as a pretext for me to address some of the challenges implied by collecting Latin American art in this country (or at least in this city) . . . I would argue that this juxtaposition is, among other things, a responsible gesture on the part of the museum; it is an acknowledgment of the never-ending narratives that museums are meant to embody and unfold, to display and convey. Like in a chess game, the relocation of a piece, its insertion or its absence, affects the whole picture. Moreover, and more dramatically, if one addresses, as this encounter claims, the insertion of a whole continent’s artistic production into our public collections, the relocation of it, and/or the presence or absence of it, then collecting Latin American (modern) art might necessarily imply the transformation of chronologies and shifting of narratives.

What is the context of those transformations and shifts? What kind of patrimonial ideology, or taken-for-granted art historical narrative regarding collecting Latin American art in American mainstream institutions, affects or transforms it? Is it an act of “reformation,” “amendment,” or “recollection of the forgotten and overlooked”? Probably all of the above and at the same time much more than the above. More generally, and pointing toward the philosophical crux of the question, one might ask: What is the destiny or fate of museum narratives at a time of overwhelming and immediate flow of information? How do we read these narratives when our culture is driven by the ceaseless dissemination of histories and by the multiplication of collective practices of syncopated, interrupted reading? When the digital world becomes a prosthetic extension of our own bodies through smart phones and other devices, and reading encompasses the syntaxes of jumping, one might consider Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov” and how it is the dissemination of information that has brought the art of narration to its exhaustion in a society in which we are no longer capable of sharing and exchanging experiences.

I am interested, therefore, in the possibility (or impossibility) of telling histories and embodying narratives in the museum today. I am interested in considering these questions: Who speaks in the museum? How might one recognize, acknowledge, identify, question, answer, or even contradict this voice? I am extremely wary of the term “Latin American art” as it seems too similar to “European Art” or “African Art.” We need to challenge its generality. We need to dismount and deconstruct its wholeness into a complex landscape of singularities in order to make it relevant for any art historical—or for that matter, curatorial—task. Otherwise, it is, or it will become, another skirmish for the politics of marginalization.

The recent interest in Latin American art by major collecting institutions in the U.S. and Western Europe seems finally to be catching up with other disciplines dealing with social sciences and humanities—it is certainly inconceivable to address the fields of economics, politics, sociology, or anthropology without taking into account the history of politics, economics, and social issues in the vast continent known as Latin America. However, until recently, that is exactly what art history and its dependent collecting and curatorial practices have done—they have established a narrative for modern art and late modernism that simply ignores the history of Latin American modernities (with very few exceptions). For that matter, and as far as the museum is also, or while it still is, an institution driven to establish narratives and to discuss history—and I speak from my perspective as a curator working in a modern art museum and as a Latin American art historian—it seems key to unveil, and maybe even to denounce, the ideology of neutrality that drives most museum narratives. In other words, someone speaks in the museum, and the museum as “someone who speaks” should at least acknowledge its grounds, its parti pris, its interests, its choices, its perspectives, and even its arbitrariness, and be open to the possibility of unfolding as a polyphonic concert of views, at best. Just as there is no single view or single history of modern art, there is no single view or single history of modern Latin American art. However, and obviously, collecting—or renewing the collection of—Latin American art in mainstream institutions implies the necessity of overcoming the “traps of the canon,” the idea of periphery as stigma, and the simplification of art history narratives as they are conceived as the exclusive result of a dialectics of formal and ideological domination and derivation. Claiming to dismount the “canon” by opposing it in its own phantomlike and antithetical duplication, labeled as its inversion (what I would call the “fiction of differences”), equals to understanding the singularities of Latin American modernity as derivative identities, as belated transferences of information (what I would call the “fable of transferences”). Beyond the fiction of differences and the fables of transferences, one needs to understand the topologies of artistic practices, their endless relocation in variable, shifting coordinates of transformation and singularization. Their relevance to the communities that share their experiences and their symbolic legacy relies on the complex net of their contextual inscription, both as diachronic events and as synchronic functions of meaning production.

It is against the phantom of origin rather than against the phantom of the periphery that our task of collecting art from the region should be driven, with the hope of signaling, through the insertion of unknown names of artists and their nameless practices, the limits of a given theory, a given narrative, or a given history—one that understands the entire constellation of artistic practices in the Western hemisphere, or at least those that unfolded in the second half of the 20th century along the East Coast of the United States: Abstract Expressionism, Pop art, Minimalism, Conceptualism, and so on . . . The schematic assimilation of art practices in the region through this simplistic system of classification relates to an operation of denial of singularities, to the annihilation of their incommensurable specificities. In that regard, one must recall that Xul Solar was much more than an expressionist painter and that do Tarsila’s legacy goes through her, overwhelming her Cubist origins as much as Torres-García overwhelms any Neo-Plasticist analogy; Reverón was not a Post-Impressionist; Lygia Clark has nothing to do with Minimalism; León Ferrari was certainly not a conceptualist and so on . . . As Fredric Jameson has argued, the “classical moderns,” or the “high moderns,” did put forth “untheorized and nameless practices,” whereas the “late modernists” were absolutely aware that they belonged to the field of modernity, embodying “the status of the artist as modernist.” Collecting Latin American modern and late modern art should imply acknowledging the problematic dimension of modernities—and modernities are problematic precisely because they exceed modernism. I am aware that I am playing here with loaded terms, but through a paraphrase of Fredric Jameson, I would dare suggest this: maybe what we so easily call (here) “modernism” is (among many other things) something like the inverted image of modernity, exactly for the same reason that the young Karl Marx claimed ideology to be the inverted image of reality. I take for granted Jameson’s thesis that modernism is the ideology of modernity, and that it is an American creation. I accept as fact that Latin American modernities can’t fit into such conceptual or interpretive frames. Rather than projecting usual, generic names onto singular practices, absorbing them through foreign categories into foreign narratives, we should project the proper, unique names of the artists, and the singularity of their nameless practices, thus embodying our plural and local modernities as a way to test the limits of already established historiographies, shifting them, transforming them. I still believe that we can understand Latin American modernity as a modern archipelago, i.e., an archipelago of modernities, in which the ceaseless dynamism of the Nachleben— Aby Warburg’s idea of formal and ideological afterlife and survival—of modernity took place and still does take place. It takes place when one refers to a location rather than a moment. In this sense, the various iterations of this afterlife of modernity that took place in the vast body of the Americas, beyond fictions of difference and fables of transference, should be understood as a topological rather than achronological set of events. Thus it is not the heterotopia of modernities that challenges us, but its topology, its yet-to-come topological understanding. Its eventual otherness is an otherness of place, not of identity—an otherness of enstellung and deformation, as in the Freudian concept of memory, in which things change because they change place. In that sense, we should accept the dimension of the incommensurable that comes with this art, as we do with any singularity once it is radically understood. Collecting Latin American art ultimately implies the idea of defying a “congruent geometry” of art history, a single, uniquely shared narrative. It is this unique narrative what is over if ever it was true. Here, I would like to evoke Jean-François Lyotard’s brilliant and enigmatic analysis of Marcel Duchamp’s transformation: the broken glass as a metaphor of a broken geometry of commensurability, where all sizes are comparable and regulated, and which is proportional to the Euclidian ideology of democratic representation. The same way in which Lyotard called us to think of a topological politics in order to understand a world where all constituents are no longer responding to a congruent, isomorphic, and homogeneous geometry, one should think of a topological art history where incongruence and incommensurability have their singular places, resonate through their full singularity. One should think of an art history in which art and artists are not the result of equations of reduction and assimilation but rather—and I quote Lyotard here—“materials, tools, and weapons for a politics of incommensurables.”

This essay is a adapted form a lecture titled “Collecting Latin American Art: Projecting Names on Nameless Practices, Transforming Narratives” presented at the symposium “The Americas Revealed, Collecting Colonial and Modern Latin American Art in the United States, in 2014,” an event organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at The Frick Collection. See the video of the lecture here.