At some point between 1980 and 1982, the Italian-born, Venezuelan artist Claudio Perna (1938–1997) deliberately left in MoMA’s library a copy of the Autocurriculum, his self-made visual compilation that contains photocopies of personal writings, reproductions of artworks, and press clippings. Beginning with the Autocurriculum, this essay examines Perna’s conceptual fixation on the fluid boundaries between documentation, artistic expression, and self-representation.

Because of its documentary nature, the varied oeuvre of Claudio Perna (1938–1997) could be read as an archive, and yet, it is the opposite of an organized and classified archive. Everything produced by Perna—a trained geographer and classifier who studied human behavior—is not only almost impossible to categorize or to date, it is also difficult to find. Perna was born in Milan, and immigrated in 1955 to Venezuela, where he became a geography professor at the Universidad Central de Venezuela in Caracas. In the mid-1960s, he began what would be a prolific artistic career, in which he explored conceptual practices based on new mediums and technologies, including film, conceptual photography, the use of photocopies, and performance, none of which were part of the local, hegemonic artistic discourse at the time. Despite Perna’s preeminence and stature among artists today, his position within Venezuelan art history remains unresolved; he is a conceptual ghost within the well-established narrative of geometric abstraction that continues to dominate the national canon.

An analysis of Perna’s body of work reveals at its core a preoccupation with the impossibility of documenting any phenomenon (experience, identity, country, territory). Pieces such as Autocurriculum (1980) and his series of maps reflect how he concerned himself with the futility of grasping things wholly—or of archiving and thus making permanent the reality (date, time, and context) of any given experience in all its facets. This fixation on documentation is also evident in his rebuttal of photography as an infallible index of reality and his reconciliation with its representational limitations. The artist’s obsession with the ultimate failure of documentation puts him squarely within the international network of conceptual artists who, in the 1970s, questioned the ability of objects to register reality. Perna’s work advanced the notions of the impossibility of wholeness and permanence, a pursuit that provided a unifying aspect in an otherwise seemingly scattered output. His oeuvre could be conceived as his continuous search for the whole, despite his full awareness that it is unattainable.

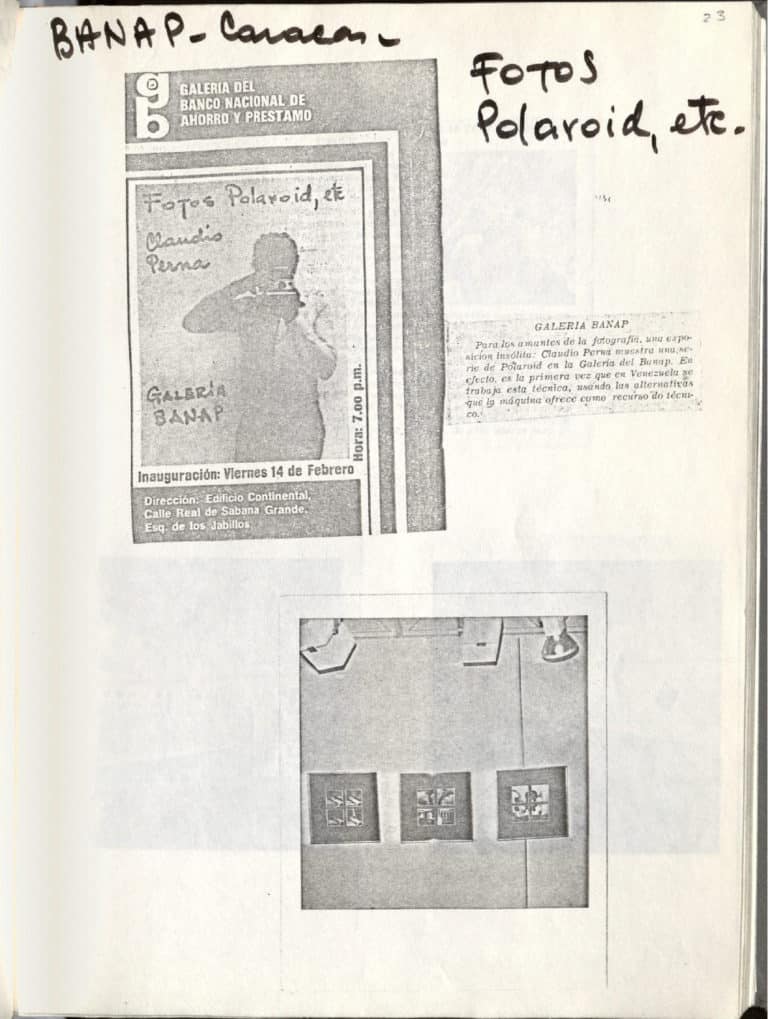

Sometime between 1980 and 1982, in an attempt to insert himself into a major art-world institution, Perna strategically left a copy of the Autocurriculum on a shelf in The Museum of Modern Art Library.11 The Autocurriculum was catalogued by The Museum of Modern Art Library on March 19, 1982. The exact number of copies that Perna made and distributed is uncertain. Besides the copy he left at MoMA and the one at the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas, Austin, at least three others were given by the artist to two of his friends: the curator Zuleiva Vivas and the photographer Carlos Germán Rojas. In doing so, he questioned the canon, first by entering it in a subversive way—as opposed to through the established channels of acquisitions—and second, by his conceptual departure from the Latin American art collected by The Museum of Modern Art at that time. A self-made visual resume, the Autocurriculum consists of 202 photocopies of personal writings, reproductions of artworks, and press related to the artist’s exhibitions between 1972 and 1980. Perna bound these materials together in gray leather, suggesting a sense of completeness that belies the inherent open-endedness of the tome’s contents. Despite its large quantity of information, the work is neither an accurate nor complete record of Perna’s artistic production. Notably, it ends with a photocopy of Il figlio dell’ Immigrante (The son of the immigrant; 1979), a work that directly references “Mi padre, el imigrante” (“My father, the immigrant”; 1945), a landmark poem by Vincente Gerbasi (1913–1992) of undeniable importance to the modern poetry movement in Venezuela. With this text, the poet seems to have relieved himself of certain memories that have tormented him and entered into a new stage of expression.

Luis Pérez-Oramas defines the Autocurriculum as an “immigrant work of art at MoMA.”22 Luis Pérez–Oramas, “El Autocurriculum de Claudio Perna, escultura social y novela hiperrrealista,” in Arte Social, ed. Zuleiva Vivas (Caracas: Galería de Arte Nacional, 2004), 61. The result of an obvious strategy used by the artist to revise his personal history, its contents show a careful selection of facts—all of which have been personally chosen, edited, and curated. As Paul de Man argues in the essay “Autobiography as De-facement,” autobiographical discourse is problematic, and begins his text: “The theory of autobiography is plagued by a recurrent series of questions and approaches that are not simply false, in the sense that they are far-fetched or aberrant, but that are confining, in that they take for granted assumptions about autobiographical discourse that are in fact highly problematic. They keep therefore being stymied with predictable monotony, by sets of problems that are inherent in their own use. One of these problems is the attempt to define and to treat autobiography as if it were a literary genre among others.”33 Paul de Man, “Autobiography as De-facement,” MLN 94, no. 5 (December 1979), 919. In the end, Perna’s use of photocopies in the Autocurriculum reveals a tension between compulsive documentation of the self and its inevitable incompleteness, which stands as an acknowledgement of the futility of such a project.

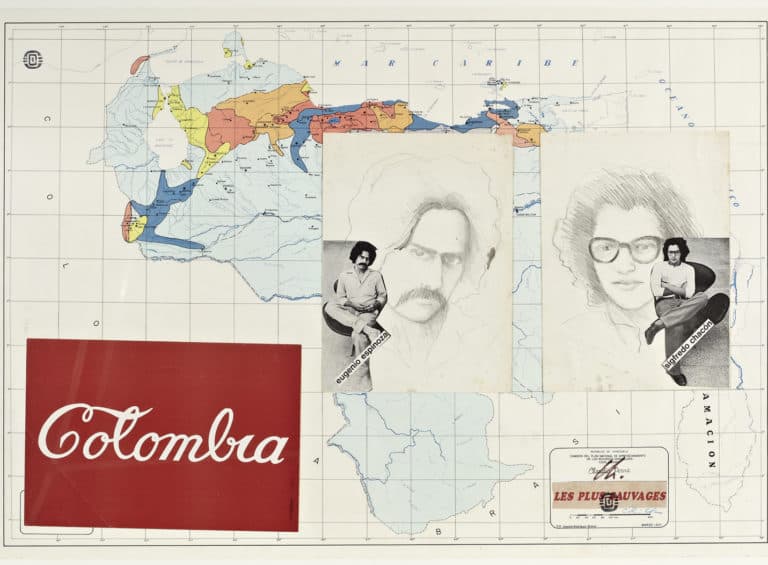

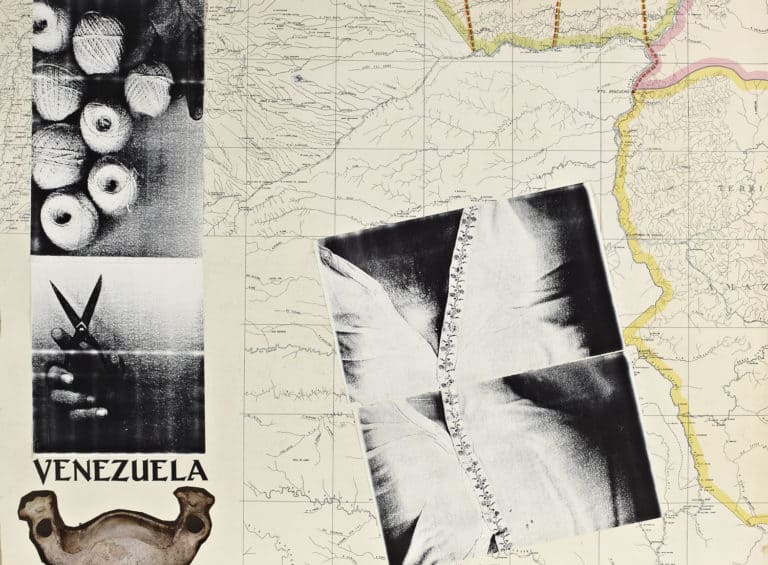

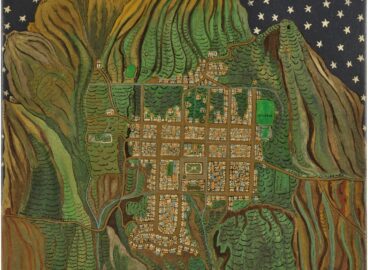

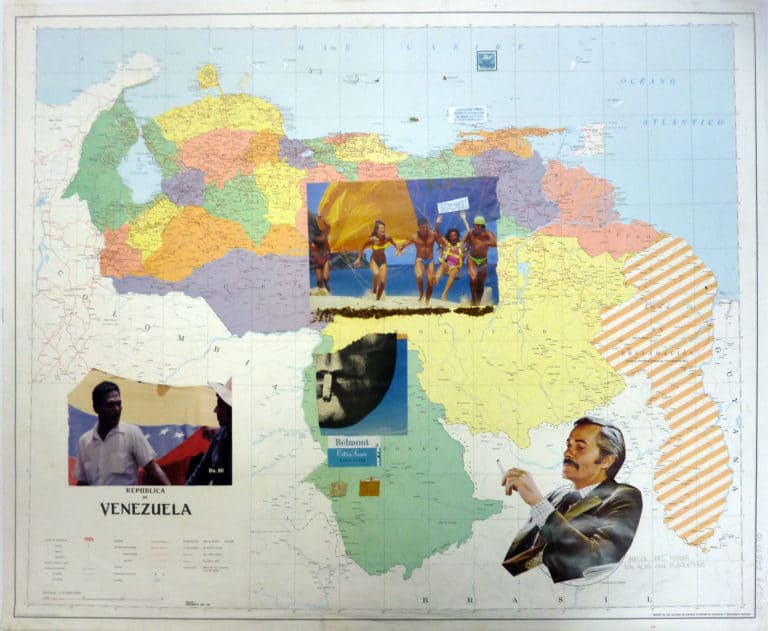

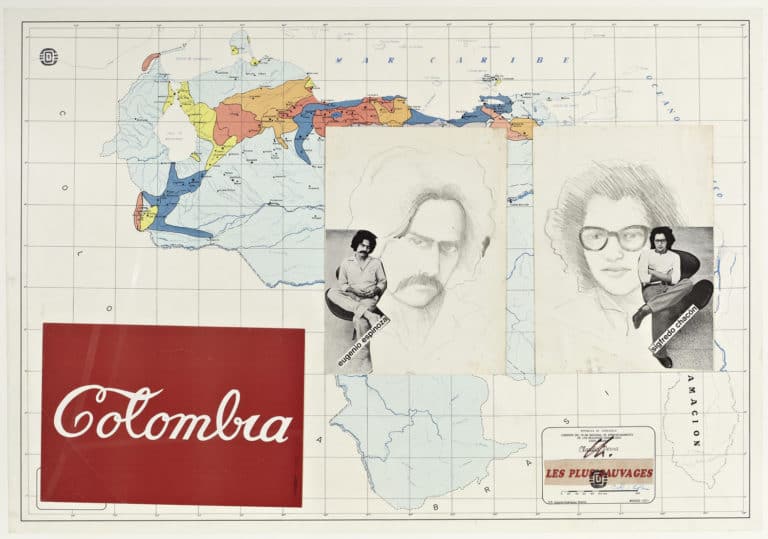

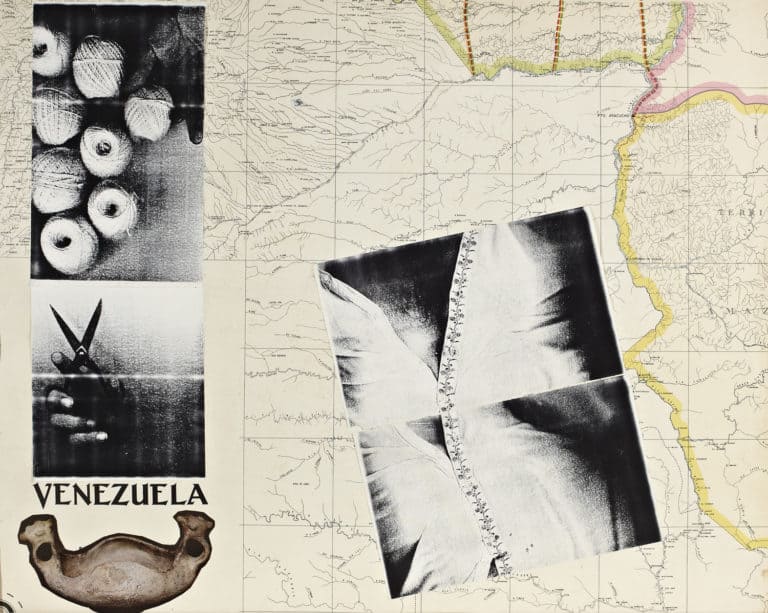

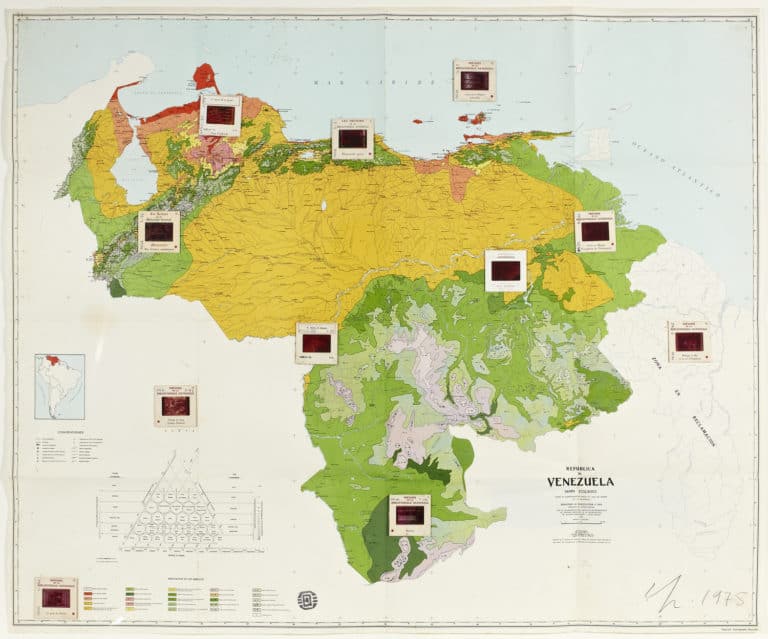

Perna’s compulsion to document also features in his series of map-based works, in which he obsessively recorded the Venezuelan national territory. This fixation is rooted in the anxiety he experienced as a result of his status as an immigrant attempting to grasp the totality of a territory—and to understand it as his homeland. In this group of images, Perna conveys Venezuela as a place of temporal and class contradictions, rather than of exoticism and modernity. Comprised of collages made from magazine and newspaper clippings and objects such as cigarettes, floppy disks, and ID cards, all of which have been pasted over different types of maps, city plans, and radar sheets, it challenges the specificities of Venezuelan territory. With the addition of self-representations, the artist further contemplated the identity that he constantly confronted. According to Czech-born philosopher Vilém Flusser, immigrants and other people experiencing crisis of identity often question: “Where am I? Where do I come from? Where am I going? What does my part of the world look like, and how do I belong there?”44 Vilém Flusser, The Freedom of the Migrant: Objections to Nationalism (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 16.

The encounters between geography and art in Perna’s oeuvre primarily focus on the Venezuelan territory, as he constantly and tirelessly worked to grasp every aspect of the country and its national identity as a way to understand his own individuality. His investigations amount to the search for heimat (home) that occupied him throughout his life. According to Flusser, the word “home” does not fully encompass the German word heimat, which has multiple connotations: home, homeland, origin, and region, often accompanied by a sense of nostalgia, or even myth. Heimat itself contains heim, referring to one’s family home or the sense of being home.55 Ibid., 1. Perna’s series of maps, with their juxtaposition of scales, technology, and multiple subject matters, represent the many aspects of different territories and his search for heimat among them.

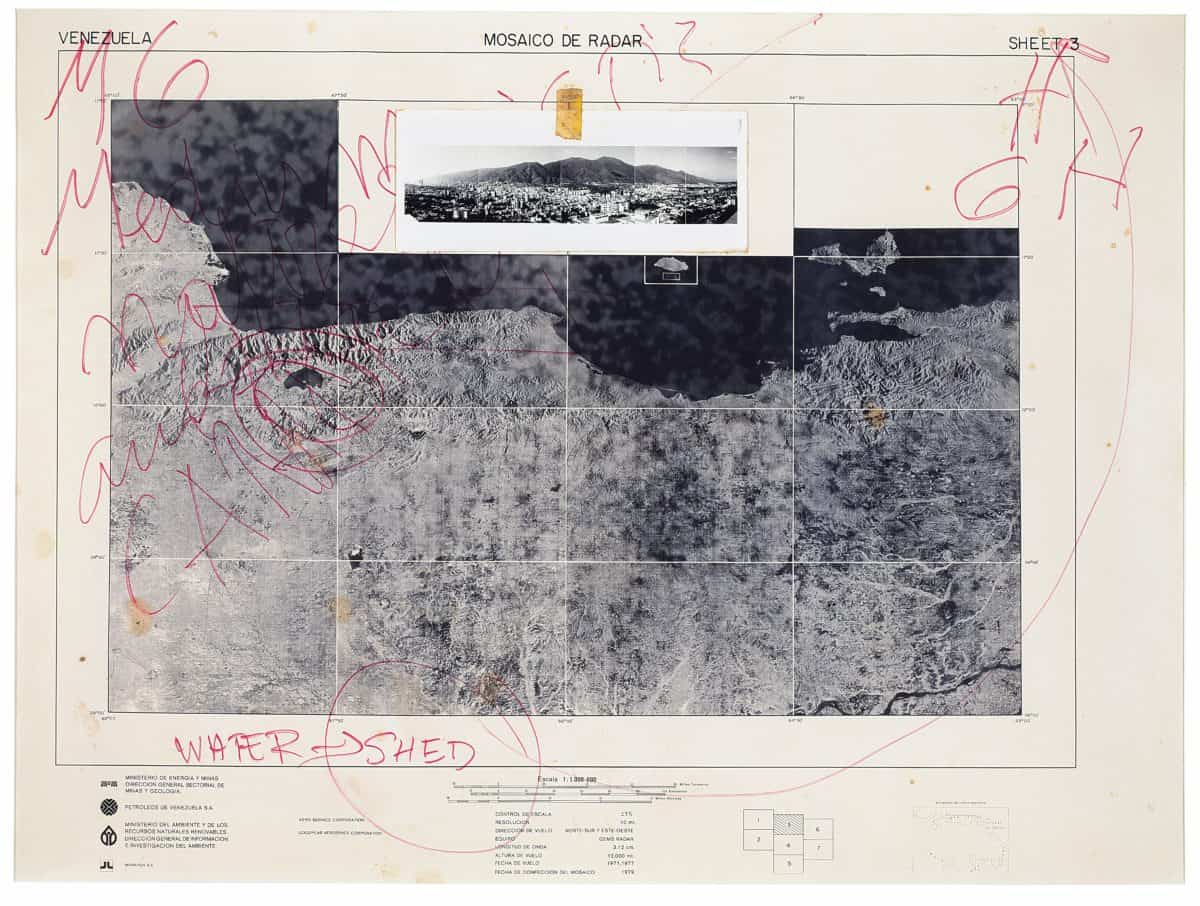

As a geographer, Perna concerned himself with Venezuela’s bodies of water, and Aerial View of Caracas, a radar mosaic image of the central northern region of Venezuela, speaks to this interest. An assemblage of small radar images that together map the whole country, this particular collage is the third of seven. The black-and-white printed picture shows the topography from above; some elevations and the water are visible in the variety of gray tones: the Caribbean Sea is at the top, the Orinoco River is at the lower right, and Lake Valencia and the Camatagua and Guárico reservoirs are in the upper left. Perna covered the image with handwritten notes made with red marker, but only the English word “WATER-SHED” is legible. His use of English shows that even though he emphasized the local, he aspired to insert himself into an international discourse—as he had attempted to do with Autocurriculum. In the center top of the radar image, Perna attached a black-and-white panoramic view of the valley of Caracas seen from the south, with the Avila mountains bordering the city to the north and separating it from the Caribbean coast. He incorporated two different photographic technologies—the radar image from above and the panoramic photograph—as well as two different perspectives with different scales on the north of Venezuela.

Perna was interested in natural resources and ecology, and with these two images, he presents water and air as fundamental resources to which every population should have access. Moreover, the two images of Venezuela are iconic: the panoramic view has been a subject of artists for more than a century, and the radar image depicts the singular silhouette of the Venezuelan coast, which through its different ports, has historically been the main site of interaction with different cultures and countries as well as a source of economic value, including as a means of oil, tourism, and commerce. In choosing these particular images, Perna indicates different modes for representing Venezuela: one scientific and the other economic, the latter always involving the interaction of people with the land.

Perna stated that there is no difference between geographic and artistic representations, and this can be seen in his focus on dispersion.66 “Yo descubrí que no hay diferencia entre postulados geográficos y artisticos”; cited in “Claudio Perna,” interview by María Elena Ramos in Diálogos con el Arte Contemporáneo: Entrevistas, 1976–2007 (Caracas: Equinoccio, 2007), 201. Everything in his work is documentary in nature, and there are two main themes: the use of technology to explore self-representation and the interrogation of mapping as a means of gaining knowledge and of exploring the relationship of humans to Venezuelan territories through the lenses of culture, development, minorities, settlement, ecology, and technology. Both themes underlie the artist’s larger inquiry into the impossibility of achieving a sense of wholeness through representation.

- 11 The Autocurriculum was catalogued by The Museum of Modern Art Library on March 19, 1982. The exact number of copies that Perna made and distributed is uncertain. Besides the copy he left at MoMA and the one at the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas, Austin, at least three others were given by the artist to two of his friends: the curator Zuleiva Vivas and the photographer Carlos Germán Rojas.

- 22 Luis Pérez–Oramas, “El Autocurriculum de Claudio Perna, escultura social y novela hiperrrealista,” in Arte Social, ed. Zuleiva Vivas (Caracas: Galería de Arte Nacional, 2004), 61.

- 33 Paul de Man, “Autobiography as De-facement,” MLN 94, no. 5 (December 1979), 919.

- 44 Vilém Flusser, The Freedom of the Migrant: Objections to Nationalism (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 16.

- 55 Ibid., 1.

- 66 “Yo descubrí que no hay diferencia entre postulados geográficos y artisticos”; cited in “Claudio Perna,” interview by María Elena Ramos in Diálogos con el Arte Contemporáneo: Entrevistas, 1976–2007 (Caracas: Equinoccio, 2007), 201.