In relation to the Māravijaya, an occurrence in the Buddha’s life that is commonly represented in Cambodian art, and Letters from Panduranga, a video work by artist and filmmaker Nguyễn Trinh Thi, art historian Ashley Thompson discusses ideas of land, gender, and colonial history. Thompson’s essay is accompanied by a two-week screening of select clips from Nguyễn’s video work.

There is a chasm between classical and contemporary Southeast Asian art—as there is between specialists in the former and the latter. On the one side is the devotional object, iconographic signification, politico-religious context, and material means—largely bound together today as in the past century by a scholarly investment in the empirical reliant especially on archaeological investigation and connoisseurial skill. On the other is theoretical exploration, where artistic and art historical practices meet to sound objectivity as a means not of abandoning the pursuit of truth but of reinforcing it, to query codification, and to push boundaries of interpretive foreclosure. Attempts to bridge the chasm are engineered, usually from the contemporary critical edge, through constructs of continuity and change, indigeneity, alternative modernities, and decoloniality—all frequently underpinned by deference, sincere or feigned, to classical knowledge—and harnessing the subaltern to the past through anthropological research. I have tumbled into its depths more than once. Here, rather than hoisting myself up to peer obliquely over the edge of the past, as I am wont to do, I am trying to eke out an existence within, probing where meaning might take root underground—between the two.

Taking “tradition” as a starting point strikes me as an increasingly anachronistic gesture, be it on the part of the artist or the art historian. The gesture is premised on the image of a static-dynamic tandem in which contemporary art is a site of research into fixed things. The premise effectively denies the multiple contemporaneities of historical objects even as it seeks to reactivate them. From the subterranean vantage point I am attempting to sustain, where roots take hold but also grow and branch, historical conditioning proceeds from the work of art as much as precedes it. The materials I am considering here are as historical as they are contemporary, and as contemporary as they are timeless insofar as they all comprise dynamic sites of practice-led research. I see that they theorize in themselves. And their work is never done. If the artworks embody theorization-in-the-making, they do not—indeed cannot—reify history or theory.

This means taking underground culture literally: seeking at once the point of view of the ancestors, buried as they are and yet made to regulate social order by virtue of their very assimilation with the enduring earth, and that of the disruptors of normativity, those who, shunted beneath the surface, are made to bolster the foundations of normativity itself. Still, mingling to make a scene that can be seen now and again, these perspectives all hold the promise of a breakthrough. At stake in exploring this common ground are, from my point of view, important dimensions of the practice of art history today as it might probe the imbrication of the normative and its challenge at the heart of the work of art, old and new.

Two artworks will ground me. At first glance, the one is on the order of a prototype: an iconography-cum-narrative reproduced in sculpture, painting, and performance with scant variation over time; the other, a film, is by contrast an original work that explores inheritance of and in art. Appealing to Hubert Damisch, we might call the iconography a “theoretical object.”1Yve-Alain Bois, Denis Hollier, Rosalind Krauss, and Hubert Damisch, “A Conversation with Hubert Damisch,” October 85 (Summer 1998): 9. The iconography has, in Damisch’s terms, “emblematic value”: it is a staid model that exceeds history not only in historical terms as it endures through repetition over time but also in theoretical terms as a site of ever-unsettled and unsettling exploration of its essential referent—in this case, the gendered aesthetics of figure and ground. The more apparently original work teases out the like emblematic value of its subjects.

Artworks

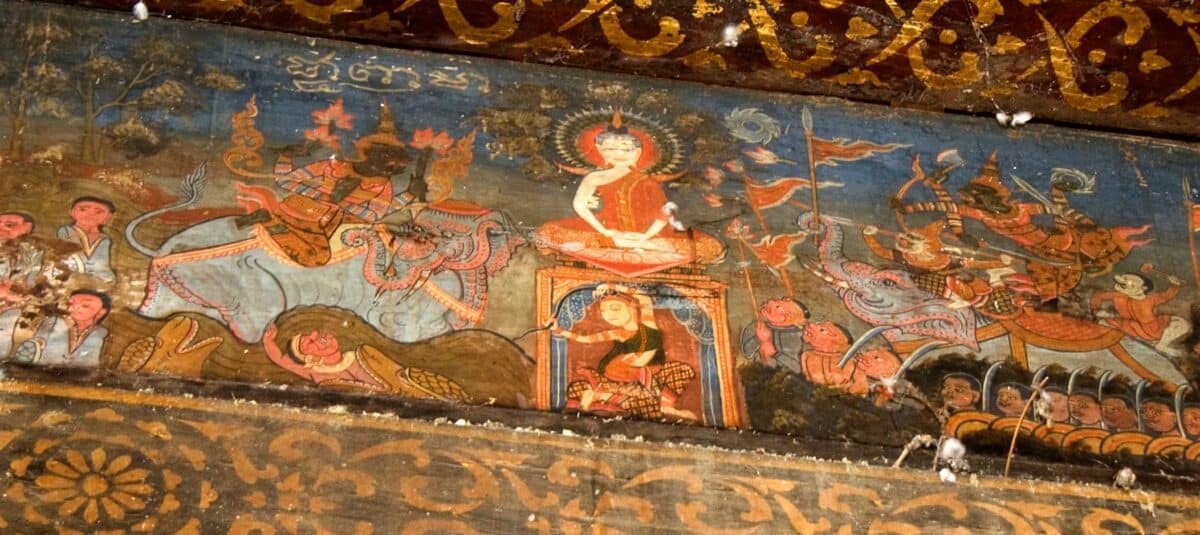

My first theoretical object is the Māravijaya scene as it typically appears in Cambodian art from the eleventh century to the present (fig. 1). I have worked extensively on this and related iconographies elsewhere, and will only summarize below the narrative and interpretive points most pertinent to discussions here.2See Ashley Thompson, “Sculptural Foundations: On the Linga and Yoni,” chap. 2 in Engendering the Buddhist State: Territory, Sovereignty and Sexual Difference in the Inventions of Angkor (London: Routledge 2016), in which I examine the Shaivite liṅga-yoni ensemble that, in subsequent work, I have understood to be akin to the Buddha-Earth Goddess ensemble. On the latter, see Ashley Thompson, “Figuring the Buddha,” in Liber Amicorum. Mélanges réunis en hommage à Ang Chouléan, ed. Grégory Mikaelian, Ashley Thompson, and Siyonn Sophearith (Paris: Association Péninsule / Association des Amis de Yosothor, 2020), 211–37; and Ashley Thompson, “Anybody: Diasporic Subjectivities and the Figure of the ‘Historical’ Buddha,” in Interlaced Journeys: Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art, ed. Patrick D. Flores and Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani (Osage Publications, 2020), 113–27. The Māravijaya, or “Victory over Evil,” is an episode in the life of the Buddha. The young Siddhartha has rejected the domestic world of the palace, the harem, the parents, the wife and child, to seek he does not know what—something more or less than the mundane. After a long period of searching for the right path, he finds himself meditating in a final approach to Awakening. A demon named Māra, the embodiment of Evil, comes to challenge Siddhartha to the throne on which he sits. Remaining nearly impassive, the Buddha-to-be reaches his right hand down to call the Earth to witness. This moment in the story is denoted by the bhūmisparśa mudrā, the hand gesture of “touching the Earth.” The Earth bears witness to the future Buddha’s accomplishments over past lives. This proves that the future Buddha’s wealth of merit exceeds that of Māra, and in such, confirms the former’s right to the throne. In the process, the Earth is shown to bear—to conserve and to reveal on demand—ancestral history in a Buddhist sense in which one is one’s own ancestor via the cycle of rebirths known as the saṃsāra. The means by which the Earth bears witness varies across time and space. In textual accounts, the Earth quakes at the future Buddha’s touch, and sometimes takes the form of a woman. The latter is the case in much Southeast Asian visual representation, and nearly systematically in Cambodian art. More specifically, a voluptuous woman with long wet hair appears out of the Buddha’s pedestal; she is standing or dancing, and wrings out her hair, making it into a weapon with which she drowns Evil.

On the one hand, the normative binary constructions could not be clearer: the prince rejects the mundane to achieve transcendence, with women—wife or Earth—as his foil, which is to say, as the pedestal on which he appears a transcendent figure, the Buddha. On the other hand, the iconographic ensemble works to deconstruct the very normative structures it nonetheless promotes. The phallic attributes of the Earth figured in the pedestal are oddly matched by the Buddha figure’s embodiment of ambiguous gender. He has shed manhood to become a “Great Man” (Mahāpurus) sublimating (hetero)sexuality in ways that align them with the non-binary if not also the female sex. In formal terms, the Earth Goddess sometimes becomes a figure in her own right, outgrowing the Buddha’s pedestal as it were to stand atop her own. The iconography is bound up in Southeast Asian “cadastral religion” as analyzed by Paul Mus:3Paul Mus, India Seen from the East: Indian and Indigenous Cults in Champa,” ed. I. W. Mabbett and D. P. Chandler, trans. I. W. Mabbett, Monash Papers on Southeast Asia, no. 3 ([Clayton, Vic.]: Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, 1975). the iconography establishing the Buddha’s sovereignty over the Great Earth, who is shown to attest to his superiority, functions also as a macrocosmic affirmation of mundane practices of territorial organization.

The second artwork, which I will argue also calls the Earth to witness in probing analogous theoretical objects, is Nguyễn Trinh Thi’s 2015 essay film Letters from Panduranga (fig. 3).4See the artist’s website: https://nguyentrinhthi.wordpress.com/2015/05/21/in-smoke-and-clouds-2015/. The thirty-five-minute single-channel video is a measured contemplation of the Cham people and heritage of south-central Vietnam. The work grew from an activist response to Vietnamese government plans to build nuclear power plants in Ninh Thuận province, Cham ancestral lands once known as Panduranga. The Vietnamese government installation would have caused yet another displacement of a people subjected to multiple colonialisms over the course of the second millennium. The Cham were once synonymous with Champa, a loose confederation of principalities located in what is now central and southern Vietnam from the fourth to the seventeenth century. The gradual expansion south of Vietnamese governance in the second millennium ultimately effaced Champa and displaced the Cham people. The shift in the ethno-political organization of the region was concomitant with a complex religious shift that saw some Cham communities embrace Islam on the back of centuries of Hindu-Buddhist practice embedded in a matrilineal kinship system. The ancient Cham material culture linked Cham peoples to their ancestral lands even as monuments fell into ruin and people moved on—or perhaps because of such transformations. From the nineteenth century, French colonial authorities worked to restore Cham temples and statues not to any contemporary owner deemed rightful, but rather as testimony to the universal value of the art produced by an ancient civilization discovered and recovered by modern colonial power. This is the landscape in which and about which Nguyễn Trinh Thi made Letters from Panduranga. As a Vietnamese citizen-artist, she seeks with her film to restitute some degree of dignity to the Cham people and places she meets.

In formal terms, the film develops through an intimate narrative exchange—a feminine voice and a masculine voice exchanging orally what seem to be the “letters” of the film’s title. The feminine voice begs seamless elision with the filmmaker, while the masculine voice conveys a sort of alter ego, in which a similar elision is nonetheless tempered with différance. The velvety texture of the two voices accompanying the camera in slow-paced trial-and-error shots of people, landscapes, and things envelops viewers in the collaborative contemplation of field encounters and techniques for engendering and adequately recording them. With notable exceptions, the filmed subjects look back at or beyond the camera but say little.5For a study of voice in Letters from Panduranga and Vandy Rattana’s video essay Monologue, see Pamela N. Corey, “Siting the Artist’s Voice,” Art Journal 77, no. 4 (2018): 84–96. Monologue is also an act of calling the Earth to witness. With more time and space, I would explore the unspoken dialogue between the two works through this prism.

Letters from Panduranga, Take 1

In an analysis of what she will finally call “an aesthetics of matriarchal potentiality”6May Adadol Ingawanij, “Aesthetics of Potentiality: Nguyễn Trinh Thi’s Essay Films,” in Lucy Reynolds, ed., Women Artists, Feminism and the Moving Image: Context and Practices (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 162. in Nguyễn Trinh Thi’s essay films, May Adadol Ingawanij alerts viewers to a fine line between repressive and progressive impulses in the assimilation of women with land: “The association of women with background and silence may superficially resemble a colonial trope of visualizing the landscape of conquest.” But Nguyễn, she argues, “complicates the commonly problematized binary, of female/background/non-speech and male/foreground/speech” by evoking a competing association, this time of artists with women, both “silenced by censorship and relegated to the background in modern Vietnam.”7Ingawanij, “Aesthetics of Potentiality,” 160–61. I want to supplement this historical commentary with further consideration of ways in which the complication of the binary engenders Letters from Panduranga’s visual and vocal fields. As the female/background/non-speech is made to emerge into the foreground of the work of art, the subject positions of artist and filmed subject are subtly exchanged. It is nonetheless the background that is foregrounded, the female who is figured, non-speech that is made to be heard. That is, the exchange does not operate a simple inversion of the binary, in which the ground becomes wholly figure and the figure wholly ground. Nor does the film arrive at a resolution fixing subject positions in their proper place. The exchange is ongoing: subject positions vacillate. Though to my knowledge we never actually see them, in the voice, the artist themself is alternately foregrounded and backgrounded, as is the woman/land/silence filmed. They are shown to be resilient and made to be so in the showing. The artwork draws from an underground power, which at the same time, it creates. The power that it makes seen is one characterized by its capacity to relinquish its own hold. The fine line between the progressive and the regressive separates the two contrary motions while also binding them. And it is this relation at work between the normative and its challenge that I see the artwork to probe as it effectively calls the Earth to witness.

There are many stand-ins for the silenced, buried woman in Letters—notably men: old Cham men whose emasculation by the consecutive colonization of Vietnamese, French, and World Heritage regimes shows on their dignified, weathered faces; Vietnamese deminers whose emasculation is hidden in plain sight by the blatant cover-up of regressive labor exploitation in futuristic garb that, along with their undeniable bravery, makes them tragic superheroes; a shirtless, beer-guzzling Cham intellectual whose emasculation finds casual, noble expression in a learned citation of Nietzsche on the joke that is life perfectly void of irony; and the Vietnamese artist’s own male counter-ego whose gentle and wise narrative voice matches her own. Still, if the women in Letters are made to show potentiality in resilience, the men are made to show resignation.

This is to say that in the hands of the artist, the binary holds the seed of its own deconstruction. The Cham/women/land are called to witness, and they do, but they do not speak back to take back; nor does the artist speak for them. Yet, in the call-and-response the artist plays out, she is more than one person, one sex, one ethnicity. The unrelenting acknowledgment of the unbridgeable gap between the artist and their subjects holds the promise of exchange and in such, uncannily and fleetingly unites them. The “matriarchal potentiality” lies then in the background as it is given form.

Letters from Panduranga, Take 2 (Clip 1)

The female narrator-filmmaker’s “favorite place to be” in the Ninh Thuận region of Vietnam is “the cemetery of the Cham Bani, who mix Islam and Brahmanism with local traditions.”8The passage examined in this section runs from 16:26 to 18:50. For a recent study of Cham Bani identity in contemporary Vietnam but with sustained historical consideration, see William B. Noseworthy and Pham Thi Thanh Huyen, “Praxis and Policy: Discourse on Cham Bani Religious Identity in Vietnam,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 53, no. 4 (December 2022): 733–61. A wide-angle shot of a full, tall tree against a gray sky introduces these words. The nearly two-and-a-half-minute passage that follows takes place in the cemetery in the middle of Letters from Panduranga. The camera pans from the treetop down. Birds sing. A mountain range comes vaguely into view in the distance. Reaching the ground, the camera pulls in to pan the foreground of boulders on a sandy surface before cutting to a woman standing on the sand among neat rows of rounded stones (see fig. 2). The background is now a low building and distant water. The woman is a bit rounded too, hair tied back, oval face, dark eyes, a long scarf draped over her shoulders with the lengths pinned down under either arm, hands clasped under her belly, a taut top, a long full skirt billowing in the wind. The camera lingers on her among the stones. Holding still for the full-frontal portrait, she seems to teeter. She averts her eyes briefly. The narrative voice continues, “Sometimes I lie down among all these stones.”

A colleague’s query brought into focus my obscure sense of the uncanny interplay between voice and image here. He asked, “Was the woman standing in the cemetery the filmmaker?” In contrast to the enunciation of the “I” elsewhere in the film where the narrator explicitly reflects on her difference from the Cham, this phrase, “Sometimes I lie down among all these stones,” suggests an identification between the narrating subject and the subject filmed. Pictured lying in the landscape, the narrator collapses the distance elsewhere made so apparent between herself and her subjects. Yet, the narrated image jars: the woman is actually pictured, that is to say filmed, standing. The resolution of this enigma follows but is no less jarring. The film cuts to a close-up of a pair of stones. The narrative voice continues, “The Cham Bani have the tradition of burying the dead on the chest of their deceased mother.” This is the first of fifteen cuts to different pairs of stones. “At each spot under a pair of stones, there might be a dozen skeletons lying on each other’s chests,” the narrative voice continues.

When she lies down among the stones, and when she pictures herself doing so in words, the narrator, it turns out, is identifying with the dead. It is a striking gesture of agency—lying down with the dead, where agency is defined as the ultimate form of passivity. In herself making like the dead, the narrator imbues a like passive agency to the stones lying on the sand as to the living woman standing among them. Any line between living and dead, as between the filmmaker and the filmed, is blurred. The camera cuts and lingers on each pair of stones just as it had on the woman. The stones also hold still under the gaze—which is to say they are made capable of movement. Do they flinch? Or do we? Once we are made to look, each pair appears different, in size, color, and positioning. They have character.

The burial image is odd: How are the dead made to lie on the chest of their deceased mother? Does the whole body not lie atop the whole body? The chest functions metonymically, that is, the pairs of stones evoke the ancestral mother’s breasts as a stand-in for the whole abstract body—ancestor and land, time and space as one.9Another study is called for here, on the Mother/Earth Goddess called Uroja—Sanskrit used in the ancient Cham language for “breast”—and what are often interpreted as breast motifs in various local art forms, including a pedestal type unique to ancient Champa. Silence ensues. The camera opens up, from one pair to show the following sequence of pairs; and out, to show many rows of pairs stretching to the horizon. The stones have taken the place of the standing woman. Was the woman standing in the cemetery a ghost?

Letters from Panduranga, Take 3 (Clip 2)

Otherwise uncanny is the incorporation of Hanoi’s Statue of Liberty into a Buddha statue in the wake of World War II and the filmic account of this historical event (fig. 3).10The passage examined in this section runs from 25:55 to 28:45. This is another take on the return of the repressed, where Nguyễn makes us see a palimpsest of narratives embedded in a single image. On one register is the “perfect study of the ‘destiny’ for the ‘colonial remnants’” as the artist-narrator’s alter ego tells it in this passage. The Hanoi Statue of Liberty, a small-scale version of the French gift to America, would become the city’s own beacon of freedom. Locally named bà đầm xoè, the “Open-Dressed Dame,” in an insider’s tongue-in-cheek critique of Western expressions of freedom, the Statue of Liberty had once stood atop Turtle Tower in Hanoi’s Hoàn Kiếm lake. She was taken down and melted down after the war as the Vietnamese gathered strength against the French seeking to reestablish colonial authority in “‘Indochina.” In literally recasting this quintessential embodiment of Western power as a Buddha statue—that is, as a quintessential embodiment of Eastern power—the repressed emerged victorious.

On another register is the filmic excavation of this story and its standing woman. The images accompanying the narration invite analysis on the model of that undertaken by the film itself, zooming in and out to discern detail, assess context, and performatively consider development of method. The passage is framed by a study of stone specimens. Someone—presumably the male speaker—holds an earthy rock up to the camera. A glass jar, with what looks like a plant rooting in water, is out of focus in the background. The hand holding the rock mirrors the camera, both unsteady, as the rock is brought in and out of focus. A small light beam abruptly illuminates its surface, which is reddish, rough, grainy. This is one of a series of specimens presented in the same manner: the presenter puts the first rock down and puts another to the same test, before then presenting a sequence of black-and-white colonial postcards also made to come in and out of focus. The particular “study of the ‘destiny’ for ‘colonial remnants”’ comes into focus as the camera homes in on the fuzzy details of one postcard featuring an engraving—Vietnamese people going about their lives on the ground. The camera moves up the card surface to reveal a tiny statue atop a building set at the far side of a lake; the narrator points her out—Hanoi’s Open-Dressed Dame—as he tells the story. The camera pulls out to show the bigger picture: a larger statue in the foreground rises above the people first shown close up. They are all set in a park. Seen from behind, the larger statue mirrors the tiny one across the lake. The man and the woman are both standing on high pedestals. They appear to face each other, communicating in the common language of their bodies standing straight and tall extending skyward—for Liberty with her hallmark right arm raised to hold a torch aloft; for her counterpart, a flagpole held to his left. The flag envelops the figure from behind to effectively expand his body in a dramatic manner: the pole appears as an extraordinary extension of his left arm. A screenshot of another postcard view of the Open-Dressed Dame rising above Turtle Tower islet across the lake, but this one, a sepia-colored photograph, is placed on top of the first, covering part of it. The camera flits between the two, highlighting different details. When the camera zooms out, we can read the postcard legend: “AUTOUR DE LA STATUE DE PAUL BERT A HA-NOI” (Around the statue of Paul Bert in Hanoi). Paul Bert was the resident-general of Tonkin and Annam for a short few months in 1886. The 2.85-meter replica of the Statue of Liberty was erected in a park at the symbolic heart of colonial administration in Hanoi in 1887. It was displaced in 1890 to make room there for the new statue of the deceased resident-general. Press reports at the time record local anger at the erection of the Open-Dressed Dame atop Turtle Tower, a monument commemorating the fifteenth-century legendary defeat of Ming Chinese colonizers and the foundation of a new dynasty to lead the independent Vietnamese state.

The humiliation can also be imagined through contemplation of the statue that took its place. Viewed frontally, the sculpture depicts Paul Bert with his right palm pressing down above the head of a Vietnamese man appearing to cower at the Frenchman’s feet.11The front of the statue appears on another postcard reproduced digitally in the Collection Henri Bosco at the Université Côte d’Azur. This archive cites historian Philippe Papin on the provocative emotional dimensions of the statuary ensemble recorded already in early colonial scholarship. See https://humazur.univ-cotedazur.fr/omeka-s-dev/s/henri_bosco/item/6046#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=928%2C1189%2C2445%2C1234. This “statue of Paul Bert” is actually a sculptural ensemble. The grand figure of the resident-general is made to stand out by the smaller figure at his feet, a figure that is, then, effectively part of the resident-general’s pedestal. Here, we see an earlier iteration of how “the colonized nations were called upon to testify to the superiority of the colonizers” in the public exhibition of “art,”’ to quote Thomas McEvilley on the symbolic work in the famous 1984 exhibition “Primitivism” in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern at The Museum of Modern Art.12Thomas McEvilley, “Marginalia: The Global Issue,” Artforum 28, no. 7 (March 1990): 20.

It is as if the colonial sculptural ensemble is a warped reiteration of the Māravijaya—or vice versa: unperturbed in their sovereignty, the men call to witness those who have gone to ground. The point is not to reduce the one artwork to the other in the name of the universal, to diminish colonial violence in eliding it with Buddhist order, or to equate two historico-culturally distinct expressions of Enlightenment leading to Liberation. Rather, it is to highlight the complex engendering of figure and ground at work at this nexus of historical settings. As history has it, many statues were incorporated like relics into the victorious postwar Buddha. But it is the French statue of Liberty that Nguyễn Trinh Thi calls to witness here to attest to the victory of the Vietnamese and in the process, now, to attest also to her own history. The filmmaker makes her reemerge from within the Buddha before our eyes, standing, right arm aloft. Like the woman in the cemetery of the Cham Bani—the filmmaker-narrator?—she too teeters in the faintly shaky hand of the presenter and the camera(wo)man. We know she has been melted down and yet she reappears, barely, like a ghost. The passage ends with the natural specimens brought back into focus.

The story is loosely reconstituted by the narrator’s alter ego as an exemplar of the truth beating fiction at its own game. Fiction, he reflects, can bring on a closer approach to the real in introducing a distance from it. The fiction the artist conjures is effectively surreal, a true story that appears so outrageous as to appear unreal. Like the shirtless Cham intellectual in Ninh Thuận province citing Nietzsche on the joke that is life.

Deep thanks to Nguyễn Trinh Thi, Nguyễn Hoàng Hương Duyên, Wong Binghao, Panggah Ardiyansyah, Pamela N. Corey, May Adadol Ingawanij, Vandy Rattana and the members of the Harvard University Collective on Gender, Religion and the Arts of Asia, for their interest and support in the development of this essay.

- 1Yve-Alain Bois, Denis Hollier, Rosalind Krauss, and Hubert Damisch, “A Conversation with Hubert Damisch,” October 85 (Summer 1998): 9.

- 2See Ashley Thompson, “Sculptural Foundations: On the Linga and Yoni,” chap. 2 in Engendering the Buddhist State: Territory, Sovereignty and Sexual Difference in the Inventions of Angkor (London: Routledge 2016), in which I examine the Shaivite liṅga-yoni ensemble that, in subsequent work, I have understood to be akin to the Buddha-Earth Goddess ensemble. On the latter, see Ashley Thompson, “Figuring the Buddha,” in Liber Amicorum. Mélanges réunis en hommage à Ang Chouléan, ed. Grégory Mikaelian, Ashley Thompson, and Siyonn Sophearith (Paris: Association Péninsule / Association des Amis de Yosothor, 2020), 211–37; and Ashley Thompson, “Anybody: Diasporic Subjectivities and the Figure of the ‘Historical’ Buddha,” in Interlaced Journeys: Diaspora and the Contemporary in Southeast Asian Art, ed. Patrick D. Flores and Loredana Pazzini-Paracciani (Osage Publications, 2020), 113–27.

- 3Paul Mus, India Seen from the East: Indian and Indigenous Cults in Champa,” ed. I. W. Mabbett and D. P. Chandler, trans. I. W. Mabbett, Monash Papers on Southeast Asia, no. 3 ([Clayton, Vic.]: Centre for Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, 1975).

- 4See the artist’s website: https://nguyentrinhthi.wordpress.com/2015/05/21/in-smoke-and-clouds-2015/.

- 5For a study of voice in Letters from Panduranga and Vandy Rattana’s video essay Monologue, see Pamela N. Corey, “Siting the Artist’s Voice,” Art Journal 77, no. 4 (2018): 84–96. Monologue is also an act of calling the Earth to witness. With more time and space, I would explore the unspoken dialogue between the two works through this prism.

- 6May Adadol Ingawanij, “Aesthetics of Potentiality: Nguyễn Trinh Thi’s Essay Films,” in Lucy Reynolds, ed., Women Artists, Feminism and the Moving Image: Context and Practices (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 162.

- 7Ingawanij, “Aesthetics of Potentiality,” 160–61.

- 8The passage examined in this section runs from 16:26 to 18:50. For a recent study of Cham Bani identity in contemporary Vietnam but with sustained historical consideration, see William B. Noseworthy and Pham Thi Thanh Huyen, “Praxis and Policy: Discourse on Cham Bani Religious Identity in Vietnam,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 53, no. 4 (December 2022): 733–61.

- 9Another study is called for here, on the Mother/Earth Goddess called Uroja—Sanskrit used in the ancient Cham language for “breast”—and what are often interpreted as breast motifs in various local art forms, including a pedestal type unique to ancient Champa.

- 10The passage examined in this section runs from 25:55 to 28:45.

- 11The front of the statue appears on another postcard reproduced digitally in the Collection Henri Bosco at the Université Côte d’Azur. This archive cites historian Philippe Papin on the provocative emotional dimensions of the statuary ensemble recorded already in early colonial scholarship. See https://humazur.univ-cotedazur.fr/omeka-s-dev/s/henri_bosco/item/6046#?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=928%2C1189%2C2445%2C1234.

- 12Thomas McEvilley, “Marginalia: The Global Issue,” Artforum 28, no. 7 (March 1990): 20.