A few months ago, Mara Polgovsky responded to Mauricio Marcin’s essay “Mail Art from Mexico (via the world): An Erratic Investigation.” The post editorial team liked her response so much that we decided to translate it to make it available in English. Please enjoy, and contribute your own discussion piece.

Mail art in Mexico in the 1970s was the result of an impulse to flight, prompted by a desire to flee from the museum, nationalism, authoritarianism, the market, and the immediacy between the production and reception of the work of art. Its fugitive character also signaled a time of disappearance, not only the disappearance of the centrality of vision in the arts, but also of the notion of a work as a complete and coherent entity. This will to flee, to escape, to flow, is the most commonly evoked characteristic of mail art expressions in Latin America. Along these lines Mauricio Marcin posits that “mail artists attempted to de-objectify creative work in order to extract it from the cycles of consumption and alienation”.1This essay is a response to Mauricio Marcin’s “Mail Art from Mexico (via the world): An Erratic Investigation.” All references to Marcin come from this text.

This process of extraction and escape inevitably ran the risk of pursuing the desire for flight to the point of invisibility, of pushing the search for immateriality to the point of art’s physical dissolution. As we commemorate these works today, however, their material status speaks of other processes that were also underway. That is to say that, in the same way that these conceptual exercises never reached the point of dematerialization, they never became islands of exile from the art world. Mail artists sought contact and, as Marcin mentions, reciprocity.

It is worth exploring the notion of “fugitiveness” through the dual meaning of the related Latin word fuga, whose second sense is lost to us today, but, as we will see below, appears to be reemerging ominously in the transformation of “fugitive practices” into their negative other. The well-known meaning of fuga refers to the notion of flight, related to the verb fugere, to flee. Its hidden root fugare, however, denotes the opposite action: to pursue something, to cause to scatter, or to encourage flight. If mail art was indeed an art of flight, this was not just owing to its focus on escape—the search for the interstitial and the ungrounded—but also because of its critical and penetrative impulses, which sought to supplant and transform certain artistic traditions. While proposing these ideas, I keep in mind specific examples, as every generalizing impulse would be inevitably challenged by mail art’s nearly “infinite number of forms,” so clearly evoked by Marcin’s ‘erratic’ reflections.

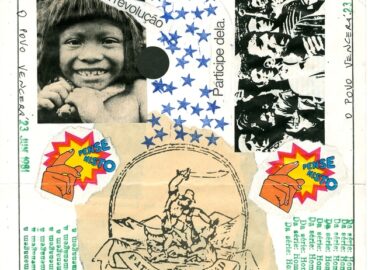

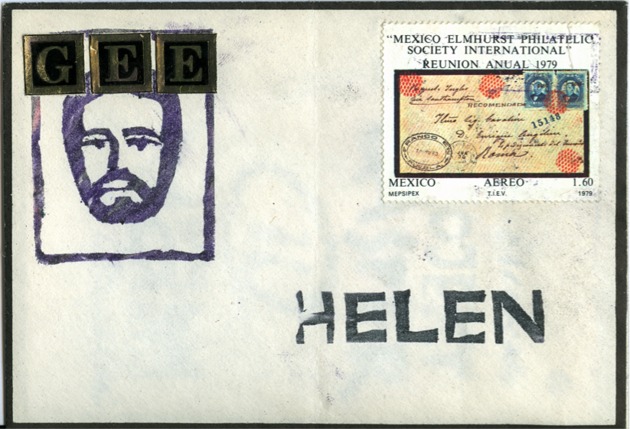

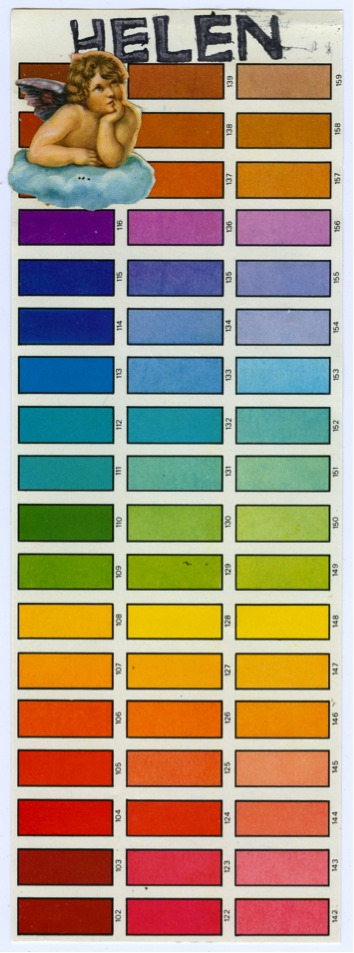

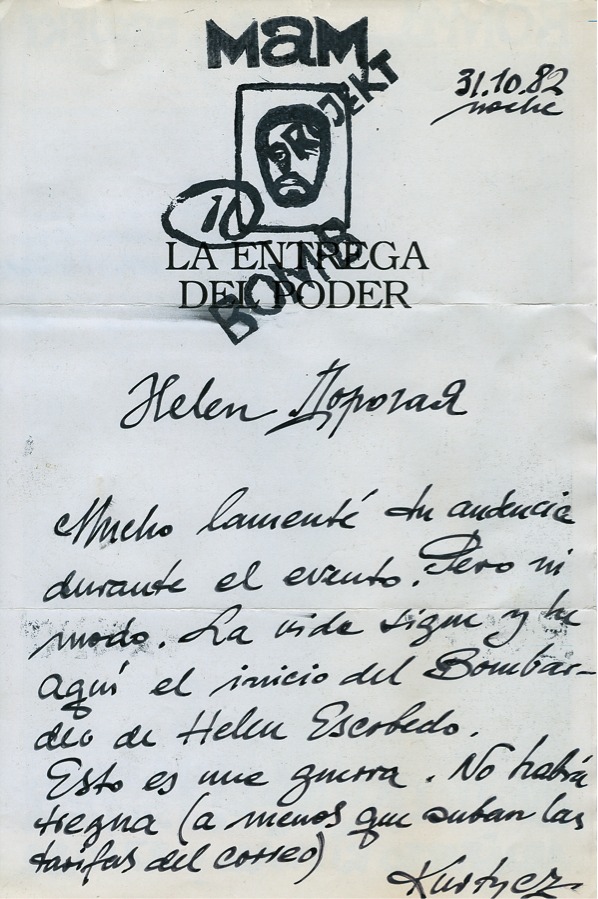

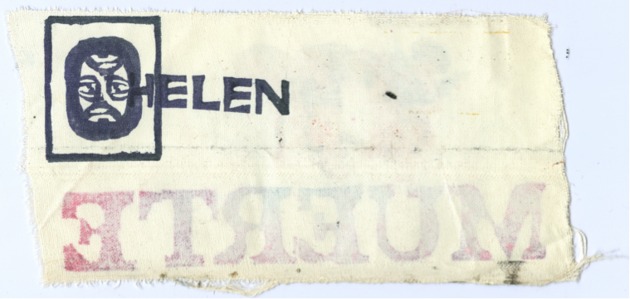

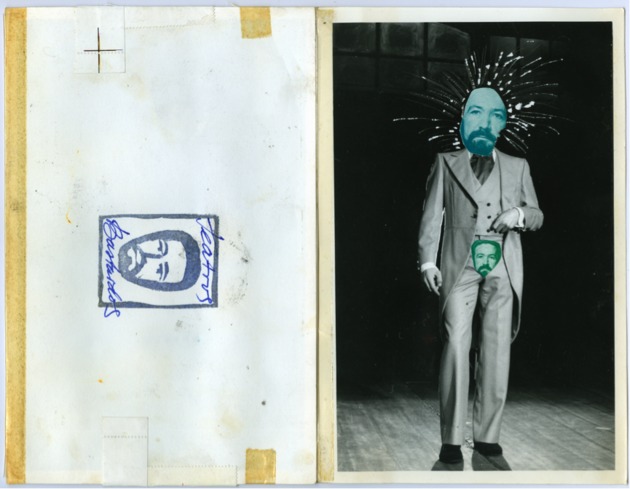

Toward the end of 1982, the experimental Polish-Mexican artist Marcos Kurtycz announced to Helen Escobedo, then director of Mexico’s Museum of Modern Art (MAM), that she would be subject to bomb attacks. This verbal threat was followed by 365 “letter bombs” (one a day for the year), which consisted of a diverse array of communications sent by mail, each reflecting the artist’s inventive imagination and his exploration of a wide range of printing techniques. The first letter, sent on October 31, 1981, reads toward the end: “It is a war. There will be no truce (unless mail rates rise).” This bracketed joke already suggests that rather than being directly harmful, aggressive, or explosive, the bombs were meant to be provocative, placing constant pressure on the institution of the museum, by pursuing Escobedo to endorse conceptualist practices, new forms of artistic experimentation, and innovative forms of relationality between the museum and the public realm. As Escobedo recalls, “Sometimes I didn’t even have time to open them, they kept piling up”.3“Conversación con Helen Escobedo”: (http://www.marcoskurtycz.com.mx/testimonios.htm). My translation. But even as a mountain on the director’s desk, Kurtycz’s bombs did not go unnoticed, if only for their arresting envelopes. Escobedo continues: “The tone of the letter bombs was varied: sometimes poetic, sometimes angry, sometimes grotesque, never straightforward.” To give a particularly striking example, one of them juxtaposes Helen’s name with the word “death” in Spanish (muerte), written backwards in capital letters. Escobedo also mentions being unsure of what to do with them, whether to thank the sender, reply, keep them, or throw them away. Exhibiting or storing them in the museum was out of the question, for in those days such objects/communications/relations were simply not thought of as artworks.

At that time the MAM and the Mexican art scene in general were experiencing crisis and undergoing an important process of transformation. According to art historian Rita Eder, “New proposals” like mail art “profoundly damaged the idea of Mexican art as conceived by the State’s cultural institutions,” which had “aimed to achieve a representation of national identity by means of established aesthetic values.”4Rita Eder, El arte contemporáneo en el Museo de Arte Moderno de México durante la gestión de Helen Escobedo (1982–1984), México: UNAM, 2010, p. 29. My translation. Escobedo’s tenure as director (1982–84), however, saw a search for renewal, opening spaces for new languages and promoting a more direct and critical interaction between artist and public. Eder argues that this process took place “in parallel” with Kurtycz’s interventions, through his mailings and periodic incursions into the museum.

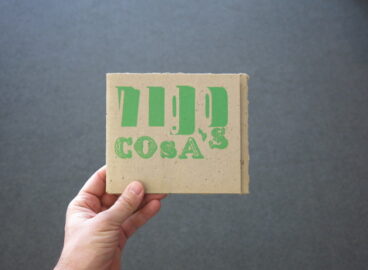

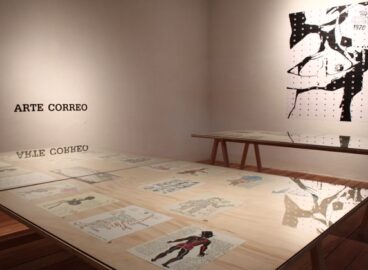

The relationship between Kurtycz and MAM in the 1980s also provides a means of reflecting on the changing times. As I write these lines (January 2014), the MAM has dedicated an entire wall to a display of mail art in the exhibition Obras son Amores (Works are Loves), curated by Marisol Argüelles and Luis Orozco. The wall contains works made between 1970 and 1990, including pieces by Santiago Rebolledo, Diego Mazuera, Gabriel Macotela, Jesús Reyes Cordera, René Freire, Walter Zanini, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Stelarc, and Kurtycz. The show emphasizes the importance of mail art in the renovation of MAM, in its embrace of new practices such as performance, its increasing interest in breaking down the distance between the gallery and the street, and “its rupture with the nationalism of the first half of the twentieth century.” It should not surprise us, however, that the show has been filled not from the archives of MAM, but instead from private archives belonging to Vicente Rojo Cama, Santiago Rebolledo, Mario Rangel, Ana María García, Armando Cristeto, Mónica Mayer, and many others whose homes and basements house the memory of this unique art of the fugue.

These basements scattered throughout Mexico, containing hundreds, if not thousands, of letters, improvised sketches,and recycled materials turned into art (or bombs) are another way of reflecting upon the two rivers mentioned by Marcin. The river of memory and the river of oblivion that run through each work of mail art are also clashing flows of intimacy and exposure, currents of privacy that nourish and intersect the construction of the public.

These notes, triggered by Marcin’s digitally published “erratic investigation” on mail art, can be concluded with a question that encourages continued discussion: is mail art a phenomenon that has “ceased to exist,” as he proposes, or, following its Heraclitean nature, has it flowed today into digital form?

- 1This essay is a response to Mauricio Marcin’s “Mail Art from Mexico (via the world): An Erratic Investigation.” All references to Marcin come from this text.

- 2I would like to thank Andrea and Miguel Kirsebon, along with Beatriz Escobedo, for granting permission to publish images 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 (all untitled), belonging to Helen Escobedo’s archive. All digital copies come from Francisco Reyes Palma’s archive, and were digitalized by Jimena Oliver. Also, thanks to Francisco Reyes Palma for the conservation of “bombs” and for facilitating their publication.

- 3“Conversación con Helen Escobedo”: (http://www.marcoskurtycz.com.mx/testimonios.htm). My translation.

- 4Rita Eder, El arte contemporáneo en el Museo de Arte Moderno de México durante la gestión de Helen Escobedo (1982–1984), México: UNAM, 2010, p. 29. My translation.