In an influential account written in 1986, a prominent British historian Timothy Garton Ash described Central Europe as “territory where peoples, cultures, languages are fantastically intertwined, where every place has several names and men change their citizenship as often as their shoes, an enchanted wood full of wizards and witches”. This evocative characterization challenged the image of the sad grey existence under socialist regimes that in the 1980s populated public imagination outside of the Soviet Block. As a result, however, the metaphor of enchanted forest only contributed to the idea of Central Europe as a far away land: inaccessible, incomprehensible, and mystifying.

15 years later a leading Slovenian theorist of art from the former Eastern Europe, Igor Zabel, could already state in the past tense: “There was once a time when people knew exactly where the center of the art world was located and where the provinces where”. His words clearly reveal the pre-1989 geopolitical hierarchies that laid the foundation for the exoticizing representation of the region. Back in 2001, Zabel’s statement was still rather a desire for the final dissolution of these hierarchies than an actual assessment of the status quo. But his words can be repeated with full force today.

In 2014, when a group of curators and researchers from The Museum of Modern Art travels to Central and Eastern Europe, it is not to experience a mythically enchanted and bewildering art scene, but to revisit old colleagues, with whom the relationship dates back decades, to meet with the artists represented in MoMA’s collection, and to try to keep up with the rapid development of the local art scenes as well as the growing number of institutions and bottom-up initiatives.

Our 10-day research trip to Central Europe took us to multiple cities whose names start with “B”: Budapest, Bratislava, Prague, Brno and Wrocław (don’t be fooled by the last one – pre-1945 it used to be called Breslau). The visit was a brisk run through public museums and artists’ personal studios, through cozy apartments and vast storage spaces, contemporary art galleries and used books stores. We decided to focus our attention on the art of 1960s and 1970s, but were too often positively distracted by the appeal of early 20th century avant-garde architecture and design that is so prolific in these cities.

Traveling like this was not possible even 10 years ago: With all the world’s knowledge accessible online at our disposal, we were able to check New York libraries holdings when exposed to a rare book on sale or access MoMA archives when in need of answers to questions about the Museum’s past travelling shows. Needles to say, it was the smartphones that possessed the most magical powers available. However, these powers could be only used well with the local help. Our generous hosts took us to back streets and alleys not visible on google maps. Here, we share our experience of these places as well as impressions and observations from encounters with art and people of Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland, as well as individuals we met on the occasion of the opening of the biennial in Berlin.

Magdalena Moskalewicz

1. BUDAPEST

At the Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art

Visiting Katalin Ladik

By Jon Hendricks

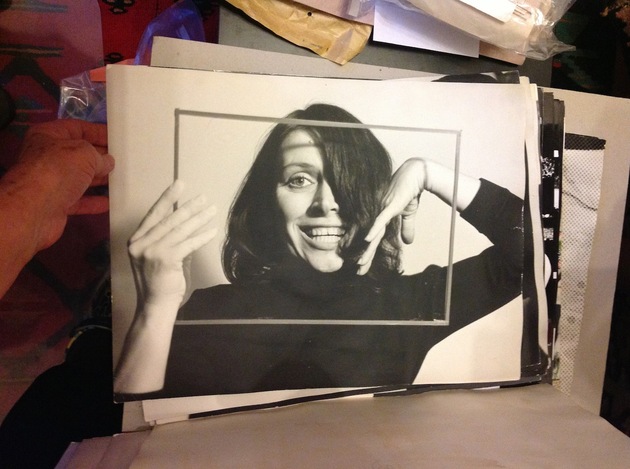

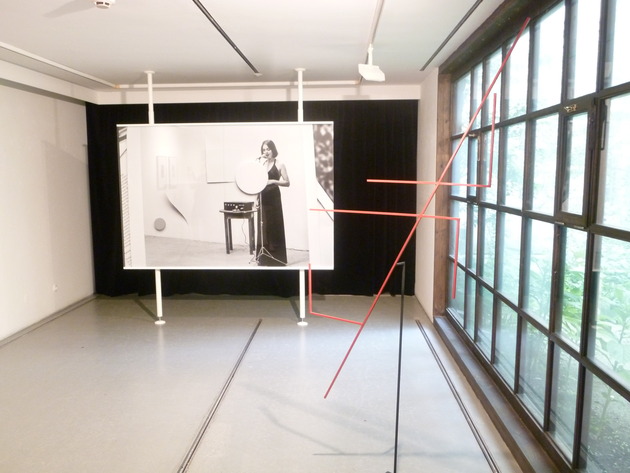

It’s hard to describe the shock and pleasure of first experiencing the work of a great artist one has never heard of. Katalin Ladik is one of those special artists who is all too hidden from public perception. On our C-MAP trip to Budapest, we had the chance to first see a group of her works at the Ludwig Museum: scores constructed of sewing patterns, seemingly random found bits of score, and other interventions. Then we visited her, and she showed us more works, works that we could look at closely, and we asked if we could hear what the scores sounded like. And then, she vocalized the scores, transfixing us. But this is not her only work. We saw more, and there is more to see: photographs of her powerful performances, poetry that mesmerized her contemporary, young generation of Hungarian artists, and a captivating soul. We were all so taken with Katalin Ladik.

Katalin Ladik’s spontaneous performance

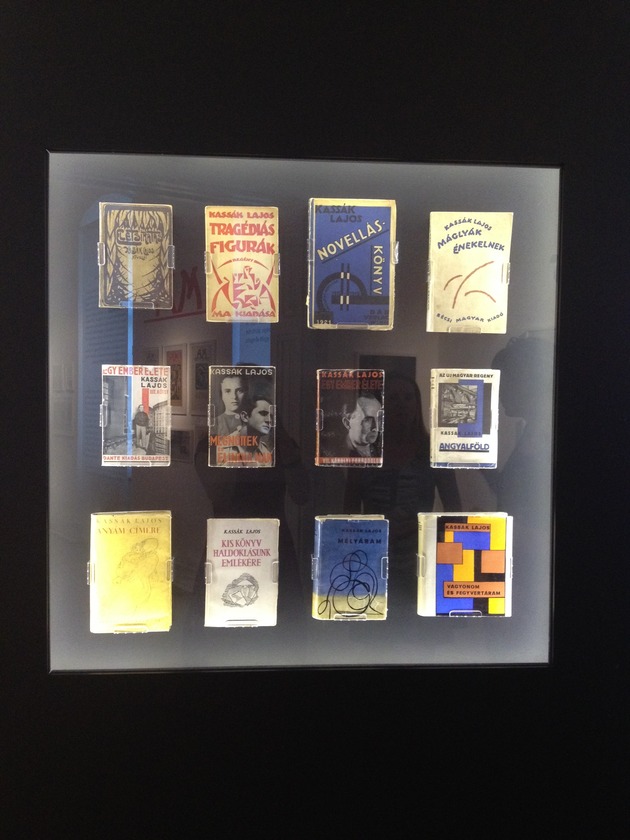

Kassák Museum

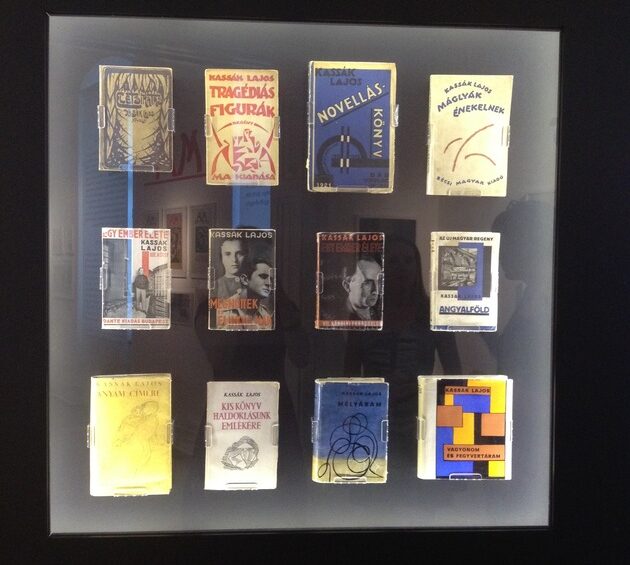

By Juliet Kinchin

On the second day of our visit, we traveled under clear blue skies to the opposite end of the city from the Ludwig Museum, to the sleepy district of Obuda, an area of lowrise 17th- and18th-century buildings that is also the site of the Roman remains of the ancient city of Aquincum. Busy main roads and high-rise housing from the 1970s now encircle those historic structures. The Kassák Museum opened in Obuda in 1976 as a branch of the Petofi Literary Museum, an affiliation that positioned Lajos Kassák (1887–1967) first and foremost as a poet and critic rather than an artist-designer In recent years this emphasis has been inverted, with greater prominence given to his work as a visual artist in the newly refurbished displays. The current installation and programming feels fresh and accessible, serving to contextualize the long career of this seminal avant-garde figure both synchronically and diachronically and exploring his diverse international connections across Europe. The museum’s present and planned activities speak to a renewed interest in early modernist avant-gardes among the younger generation of curators, historians, artists and designers. The bold design of the new permanent displays effectively complements but does not overwhelm the art and documentary source material—a particular challenge, since the collection of works in various media is graphically so strong. The red and black display furniture and exclamatory texts screened directly on the walls blend with the more intimate scale of the printed ephemera on display.

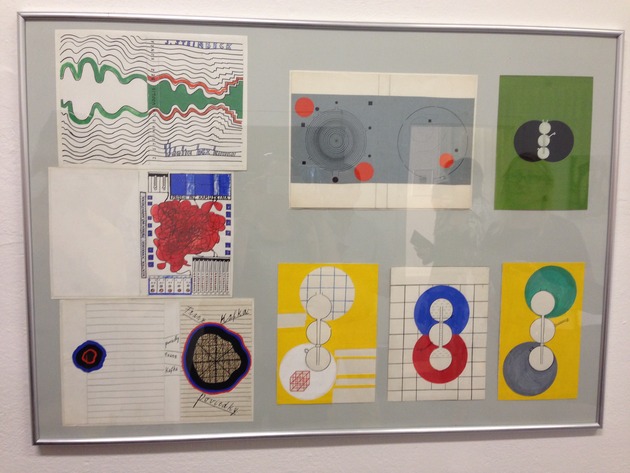

János Szoboszlai and Katalin Szőke talked to us about the current thematic exhibition, Kassak and Kassak 2. The show addresses Kassák’s reworking in the 1960s of his 1920s output, a project undertaken after a successful exhibition in Paris. Questions of authenticity and originality have been a long-standing problem in considerations of Kassák’s early and later works. In tackling this question head-on and unraveling the complex history of Kassák’s 1960s reprints, the museum is offering fascinating perspectives on the trajectory of the artist’s practice and reputation on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

This is one in a series of research and exhibition projects on the historical avant-garde in Hungary undertaken by the staff at the Kassák Museum. Another currently in progress and outlined by curator Katalin Szőke during our visit is an international, interdisciplinary examination of Budapest’s dance and movement avant-garde of the 1920s, paying particular attention to the experimental pioneers Valeria Dienes and Alice Madzsar. Embracing numerous key figures in Central European art, music, drama and dance, this project whose development we will be watching closely over the next year or two.

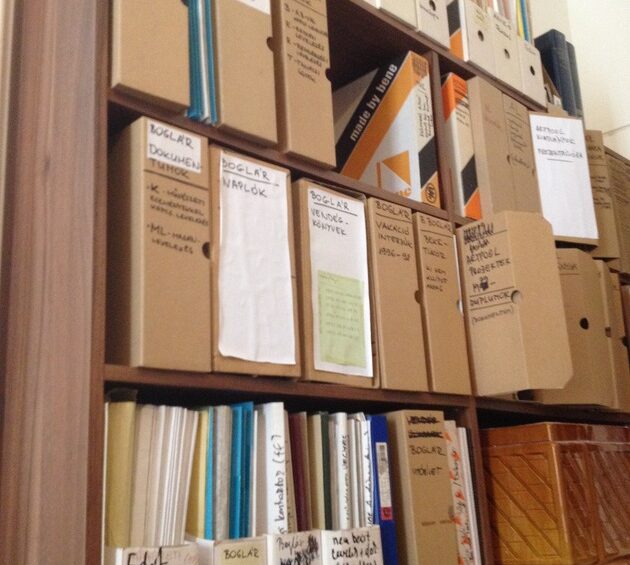

Artpool

By Milan Hughston

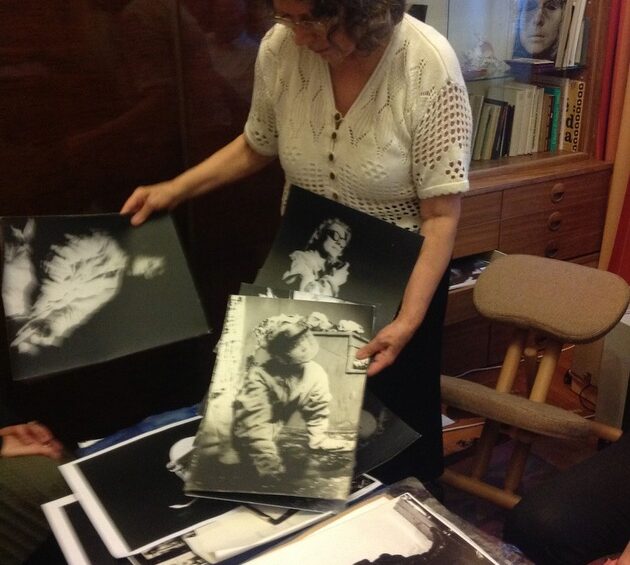

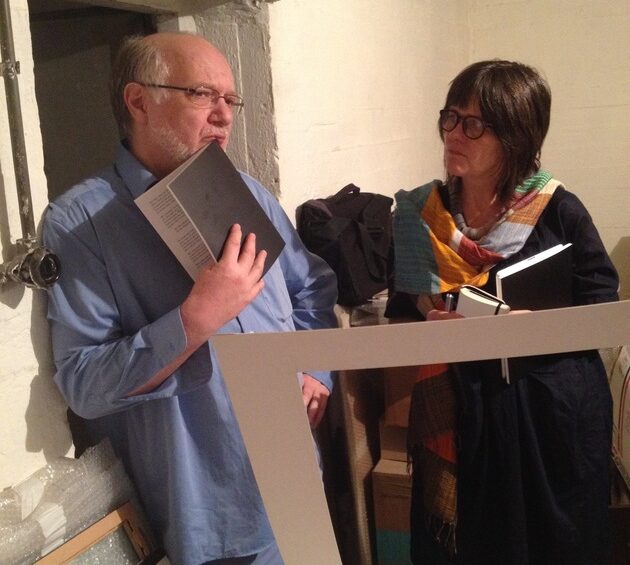

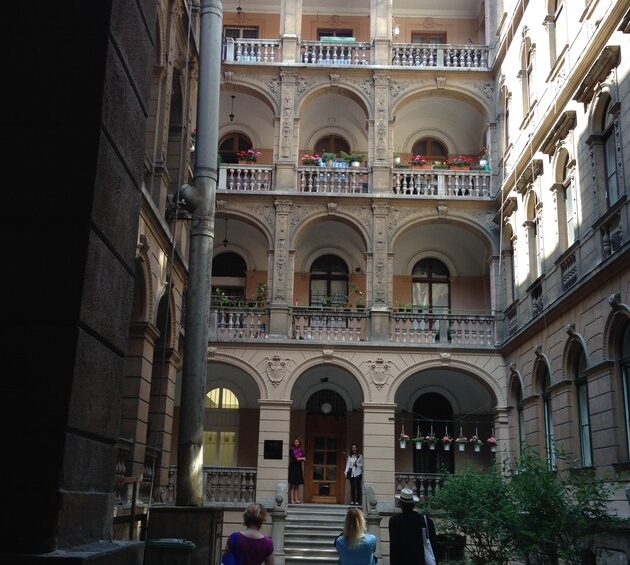

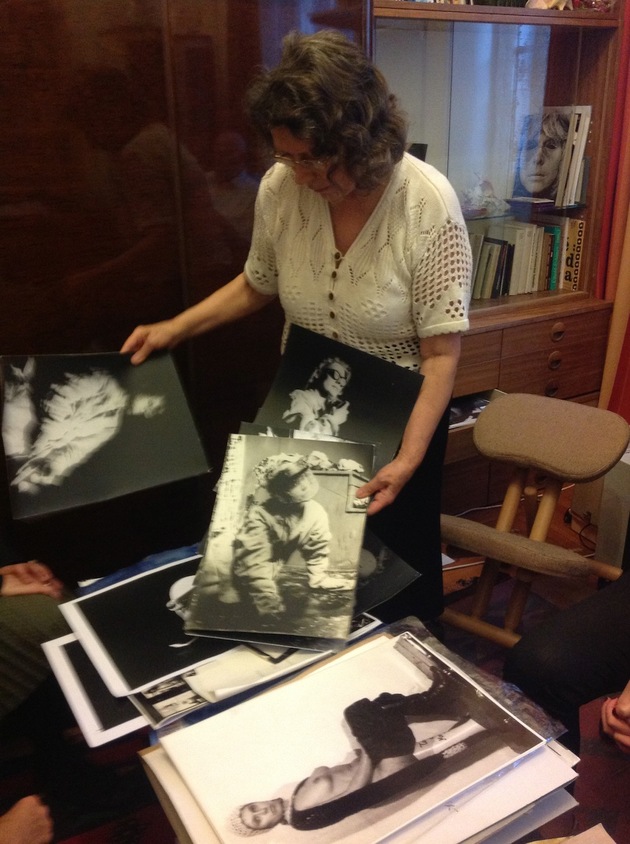

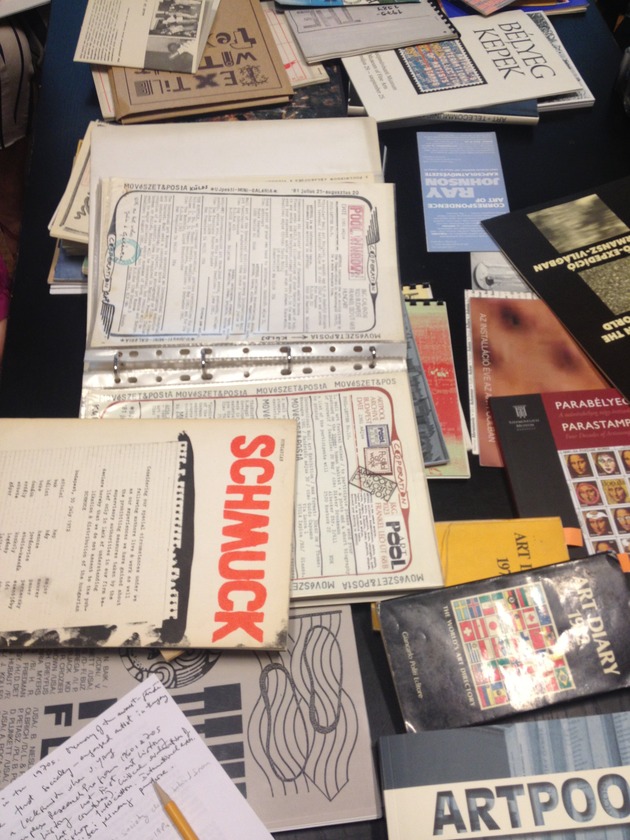

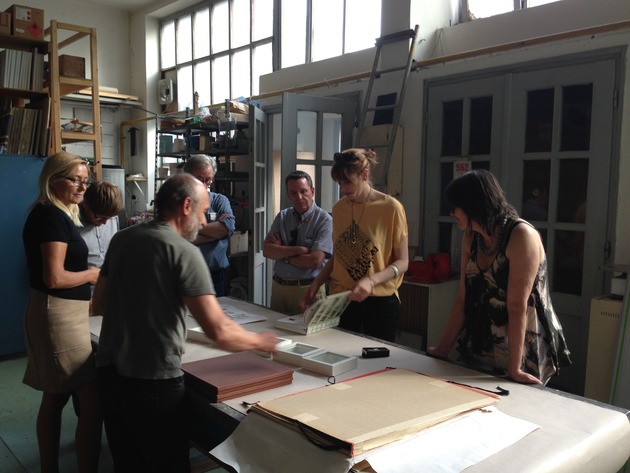

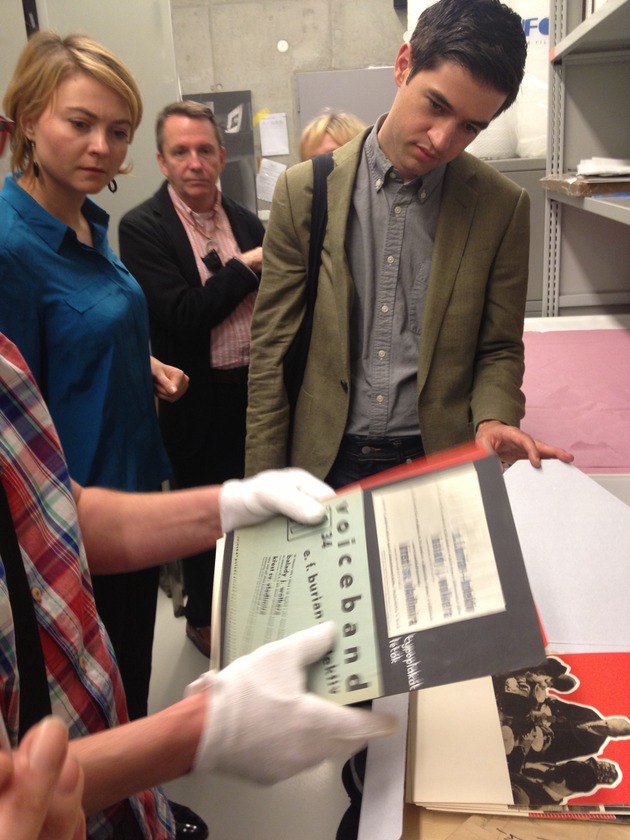

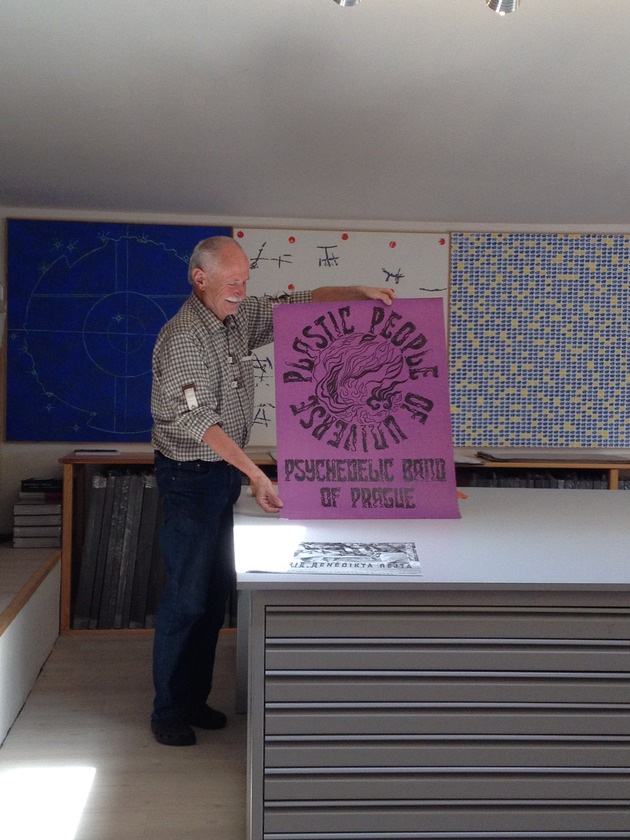

The group’s focused visits in Budapest included a site visit to Artpool, one of the most active and comprehensive collections of experimental art practice in Europe. We were hosted by its founders, Júlia Klaniczay and György Galántai, at Artpool’s large archive located in the heart of Budapest.

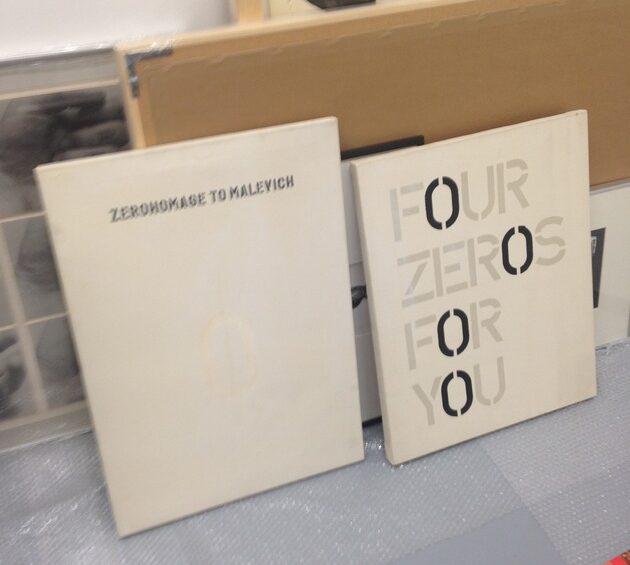

Artpool was established in 1970 to produce, network, curate, and document avant-garde art practices in all formats. The resulting collection is astounding in scale and scope, covering contemporary art practice from the 1970s to the present.

In 2013, Artpool published a 535-page history of their efforts in a beautifully produced catalogue that is available in its entirety through the MoMA Library online catalogue.

In spite of their success, Artpool and its founders face serious financial and space issues in the contemporary climate of Hungary. It is vital that this unique centre of visual art action and documentation continue to tell its story.

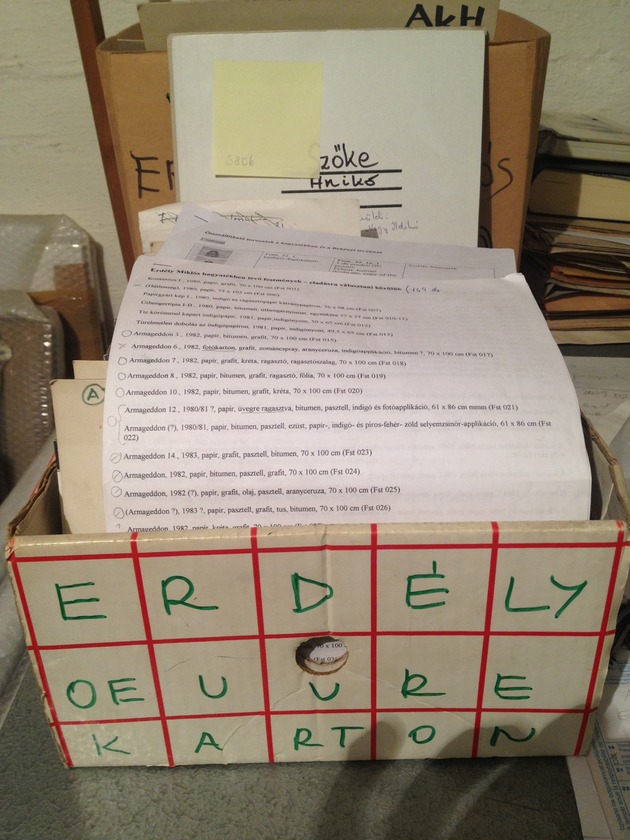

Miklós Erdély Estate

Views of Budapest

At Budapest Art Galleries

Meeting with Tamas St.Auby

By Jon Hendricks

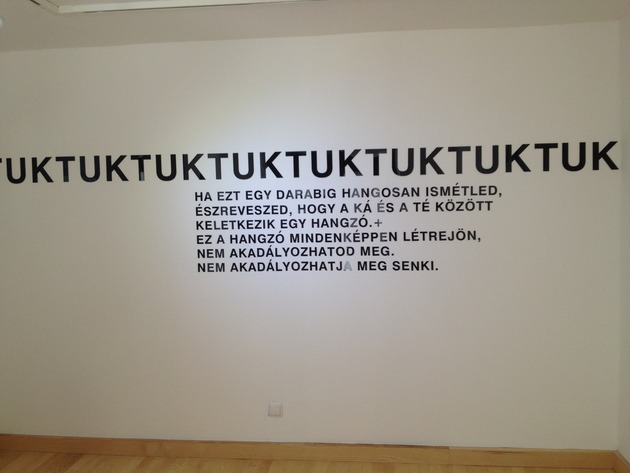

Tamas St. Auby is a legendary figure in the avant garde. He is one of them. He continues to be one of them. You kick over a stone, and there he is. You open a door and peek in— there he is. Hungary hid from him for twenty years. The art world has hidden from him even longer. What are we afraid of? His mind is a provocation; his mind is a revelation. He has so much to say, and our group was treated with an amazing and lucid presentation of his work.

Walk through modernist villas in the Napraforgó street, with Pal Ritook and Ardnas Ferkai

Villas in Napraforgó utca

By Juliet Kinchin

Given Budapest’s spectacular and rich architectural fabric, it has been disappointing to learn of the closure of the Museum of Architecture formerly situated near the Kassák Museum in Obuda. The entire staff has been dismissed (except for the current director Pal Ritook) and the collections have been removed to inaccessible, off-site storage pending possible inclusion in an expanded fine arts museum campus in the Varosliget. An equal if not greater loss is the closure of the museum’s display space in the Castle District and the program of excellent traveling exhibitions that the museum organized regularly for venues throughout Hungary and abroad.

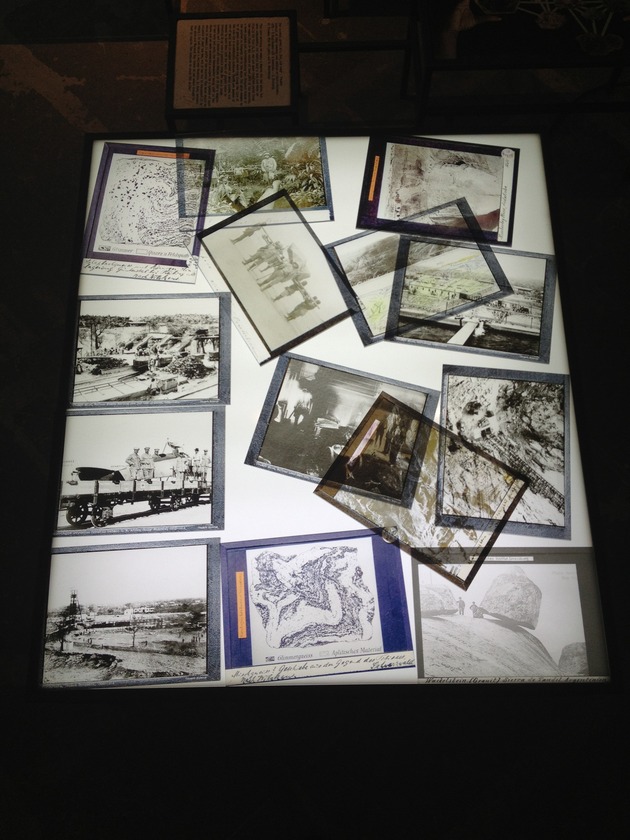

Despite these problems, Ritook and Prof. Andras Ferkai of the Moholy-Nagy Művészeti Egyetem (Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design) prepared a collection of archival materials that they circulated during our architectural walking tour of modernist villas in Napraforgó utca (literally Sunflower Street) in residential Buda. Having started the day with a focus on Kassák and modernist graphics, a few of us ended the day with another journey back to the utopian future in this delightful enclave of early 1930s modernism, a legacy of Hungary’s influential participation in the Bauhaus. We began in Pasaréti tér, a square framed by a modernist bus station on one side and a Roman Catholic church and monastery on the other, all designed by the architect Gyula Rimanóczy in 1933. Alongside this is Napraforgó utca, an ensemble of twenty-two modest family houses built in 1930-31. This project was the culmination of several years of campaigning to encourage the authorities and the public at large to adopt modern principles in house design. It started in 1925, when Farkas Molnár, a star graduate of the Weimar Bauhaus and an assistant in Walter Gropius’s architectural office, returned to Budapest to spread the modernist gospel. Pointing to the success of the 1928 modernist housing exhibition at the Weissenhof estate in Stuttgart, Molnar and a group of up-and-coming architects petitioned the Budapest Public Works Council in 1930 to build a whole street of small houses. The group also included Jozsef Fischer and Lajos Kozma, the finest modern architects in Hungary. The names of all involved appear on a stone block at the center of a small square on one side of the street, where locals still gather to chat and play. This project, like the one in Stuttgart and others in Wrocław (then the German Breslau) and Prague, was to demonstrate that the main task of modern architecture was the construction of practical, affordable housing and rationally designed buildings. The neo-conservative social and political climate in Hungary between the Wars meant that, compared to Germany and the Netherlands, the country had very little public or collective architecture. Rather, new modernist ideas were applied mostly to the design of single-family homes and villas. Within a year of the initial proposal, the twenty-two houses had been built. With all of the architects working on plots of the same size, this little development shows what a small group of enthusiasts with a utopian vision could achieve in a year.

2. BRATISLAVA

Bratislava City Gallery

By Juliet Kinchin

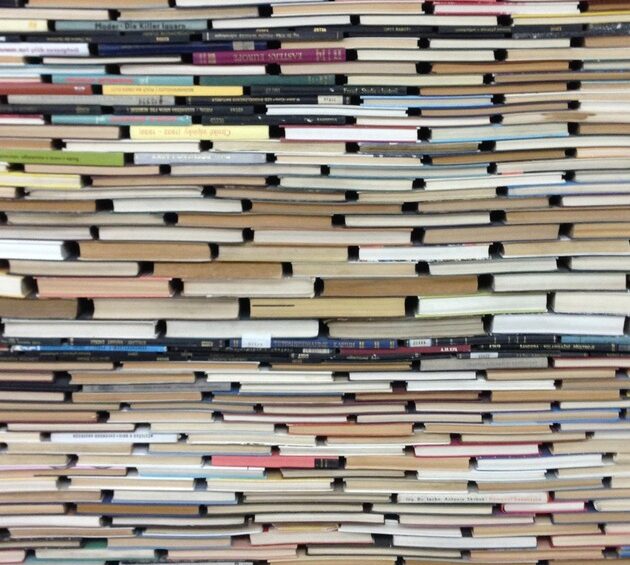

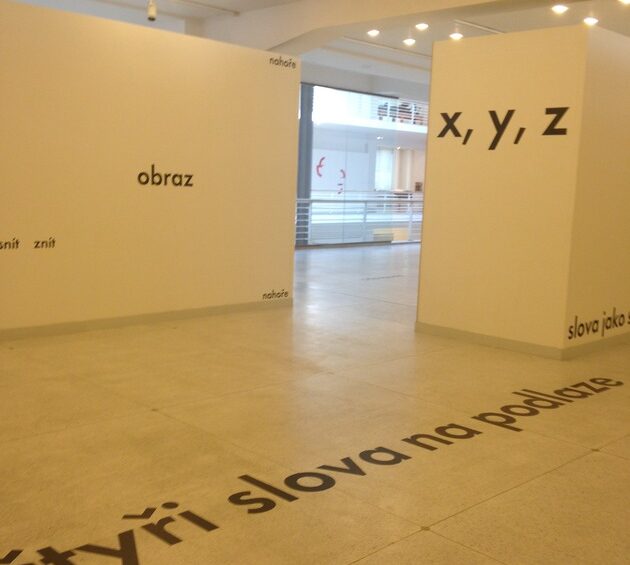

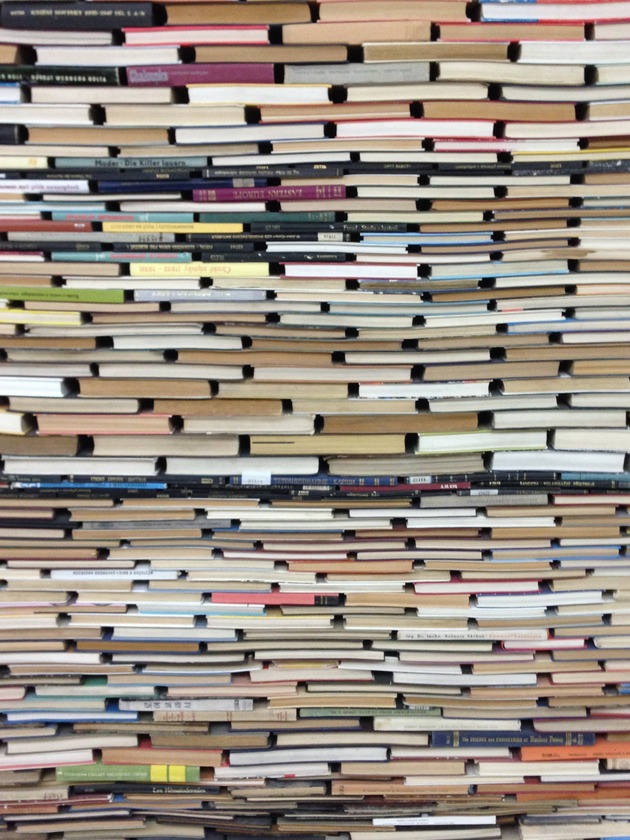

It did not take long to travel from Budapest to another country and to Bratislava, the second of five cities on our itinerary beginning with B, if one counts Breslau, now Wroclaw. Traveling between these major cultural centers in a minibus was a reminder of how diverse and concentrated Central European culture is, with different peoples, languages, styles, and values often co-existing in cities just fifty or sixty miles apart. In Bratislava, we were met by Juraj Carny and taken directly to the City Gallery in the heart of the Old Town. In advance of the string of meetings scheduled with artists that afternoon, the gallery’s survey of Slovak conceptualism of the 1960s and ’70s (Koller, Bartoš, Filko, Sikora, Mlynárčik, Ďurček, etc.) gave us an excellent overview and preparation. Chief curator Zsófia Kiss-Szemán explained that there had been a great push in recent years to build up this part of the collection, which in its totality ranges from the Gothic to the art of the present. Some types of work fared better than others in the relatively intimate and historical atmosphere of spaces carved out of a former palace. One of the most successful was the vertiginous passageway created by Matej Krén between seemingly endless walls of books. Proceeding gingerly along the narrow path that Krén describes as a kind of symbolic “short cut across the world”, we felt the weight of the inaccessible knowledge locked within the tomes on either side. The books were those censored or discarded in Communist times.

Galéria Cypriána Majernika

By Juliet Kinchin

Despite a prevailing climate of censorship in the 1960s and the controversial closure of several of its exhibitions, the Galéria Cypriána Majernika clearly provided an important forum for young Czechoslovakian artists under the age of thirty-five. A state-run organization similar to Young Artists’ Centers in several other Soviet Bloc countries, the gallery had the prerogative to retain work by the artists it showed. The collection that has accumulated in this way is a fascinating time capsule of semi-official art from the 1960s to the 1980s, with limited additions of more recent work. I was particularly intrigued by a picture entitled Tesco Woman. Originally painted by Julián Filo, a politically engaged artist of the 1980s, it has been given a contemporary makeover by Veronika Rónaiová – the artist’s daughter. Due to the current restructuring of visual arts venues in Bratislava, this gallery’s function has been largely superseded. With the transfer of former director Richard Gregor to the City Gallery and a tightened budget, it remains to be seen whether the Galéria Cypriána Majernika can reinvent itself to perform a new role in the visual culture of post-Communist Slovakia.

Seminar with Slovak Artists and Curators at Kunsthalle Bratislava

Milan Adamčiak

By Jon Hendricks

Our trip to Bratislava was my first trip to Slovakia and my introduction to a number of marvelous artists and very generous and gracious curators and directors of cultural institutions. I was very taken by the work of Adamčiak, whose intriguing art takes several vigorous forms. He described an early piece where he went under a bridge and played his violin under water. It must have been so beautiful. He entranced us with descriptions of other sound explorations and innovations. We were shown scores that he has composed; it was so marvelous to be introduced again and again to artists who have been working with scores and sound art in the various cities that we visited.

Stano Masar

By Michelle Elligott

During a full afternoon conference organized by the Kunsthalle Bratislava, which was commenced by an excellent overview of Slovak art from the 1960s-on by Chief Curator Richard Gregor, we enjoyed presentations by a handful of artists. Stano Masar presented an overview of his practice. Notable are his two series of Global History of Art, 2004 and Contemporary Art, 2007. In these series, Masar selects icons of art, from old masters to recent wonders, and translates them, if you will, into the language of infographics to create uniform pictographs. The artist succeeds in distilling the image to its immediately recognizable, core form – its dna; utilizing the pervasive international language of graphic signage; and instilling a hint of humor to create a wonderful body of work.

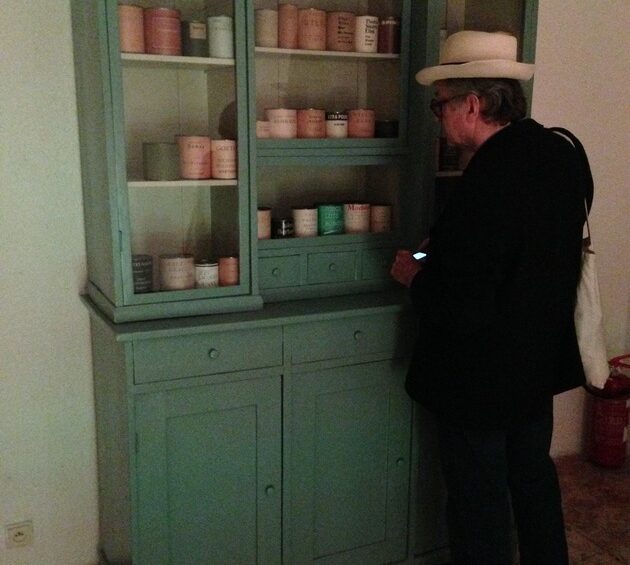

Studio visit with Otis Laubert

By Milan Hughston

While visiting Bratislava, Jon Hendricks and I were taken by Juraj Carny to the studio of Otis Laubert, a Slovakian artist born in 1946. Upon arrival, it was apparent why a studio visit to Laubert’s home and workshop was necessary to understand the full breadth and scope of his work. The studio and home are located in a dense warren of buildings located in a suburb of Bratislava. It is a wonderland of found objects beautifully incorporated into all mediums—collage, paintings, and furniture, to name just a few genres.

Artist and theorist Jiří Valoch characterizes Laubert’s practice succinctly: “We could say Otis’s major summarizing work is his deposit—the collection of various objects, originating in about 1965 and containing thousands of things ordered according to certain rules.” Our visit with Laubert confirmed that.

Monogramista T.D.

By Jon Hendricks

Later that same afternoon that we met Milan Adamčiak, we visited the studio of Monogramista, an artist who also works with scores and installations. Unfortunately, we did not have the opportunity to hear his works, but visually they were very striking and beautiful. I look forward to seeing more work by Monogramista and Adamčiak and hope we will have the opportunity to meet both again soon.

Studio visit with Monogramista

Tranzit.sk

3. BRNO

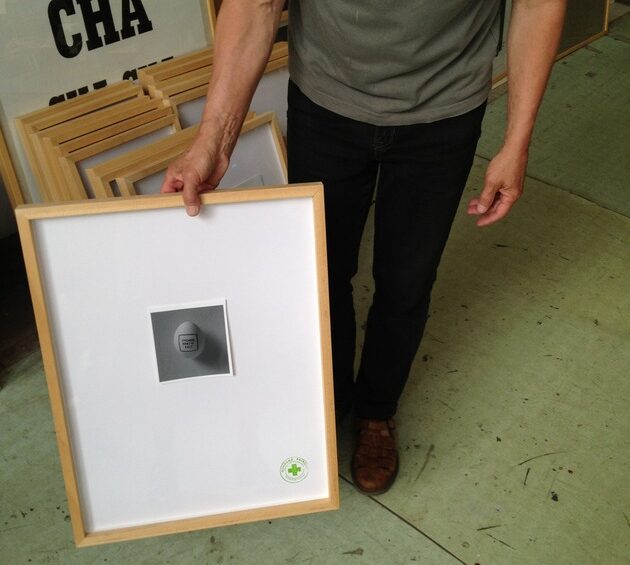

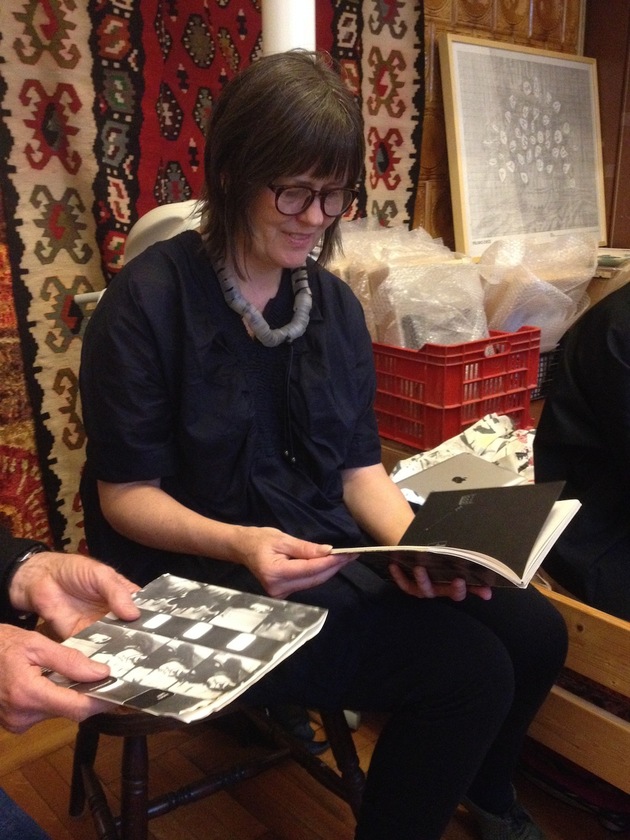

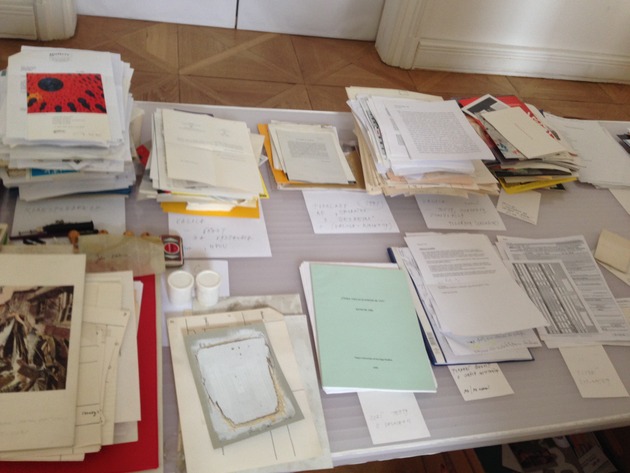

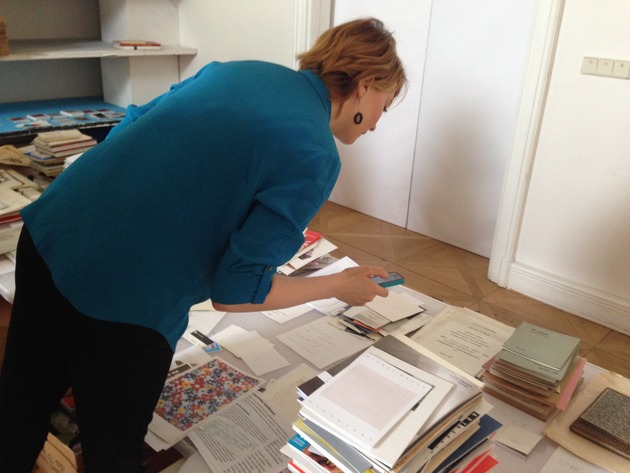

Moravian Gallery – Jiří Valoch Archive

By Michelle Elligott

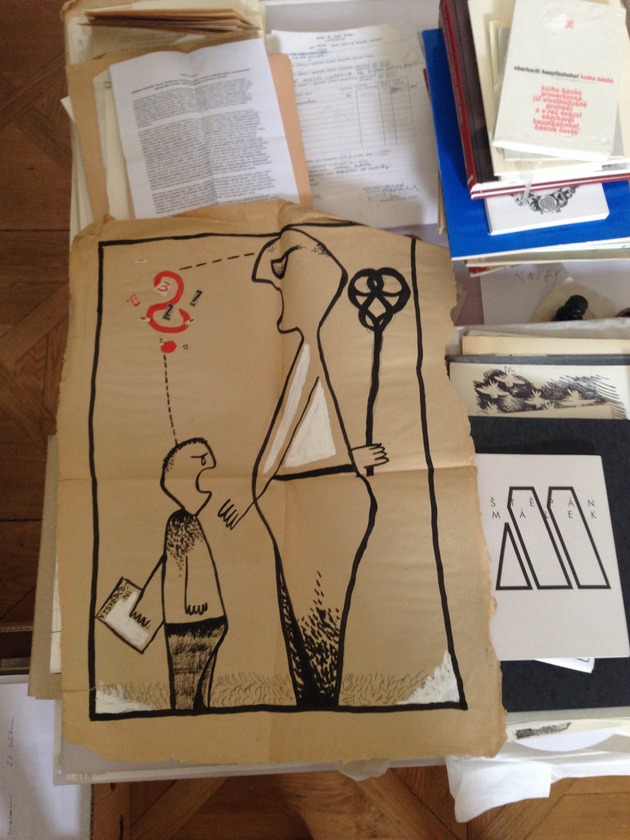

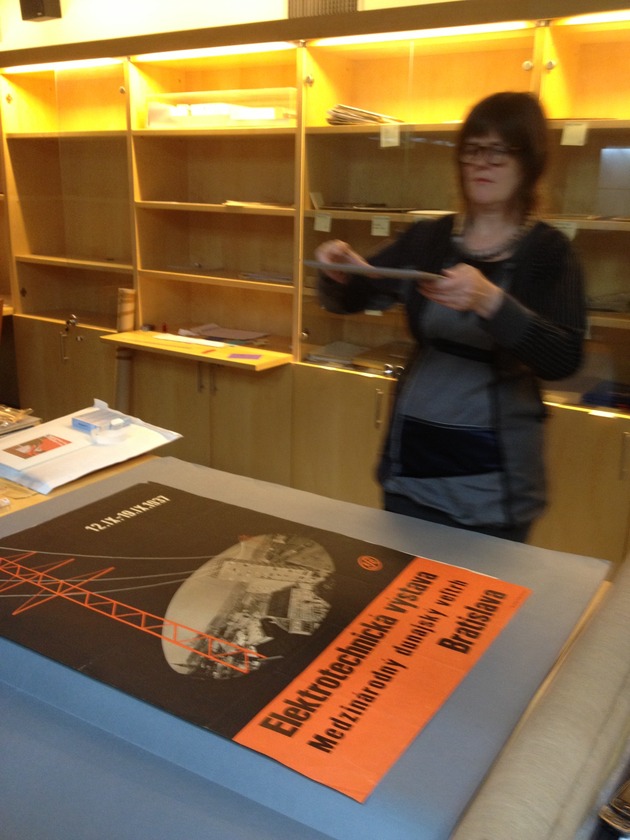

Moravian Gallery graphics

By Juliet Kinchin

In 1961, the same year that the Bratislava City Gallery was established, Brno’s Museum of Applied Arts morphed into its current form as the Moravian Gallery of Art. With rich historical collections, several branch museums and ambitious plans to accommodate the living archive of Jiří Valoch and other contemporary artists from the region, it remains the most significant cultural institution in Brno. Curator Marta Sylvestrova took time out from the final stages of preparation for Brno’s renowned International Biennial of Graphic Design to lead a few of us behind the scenes. I was particularly keen to explore the posters and graphic design collection and to catch up with her research for a forthcoming exhibition on Zdeněk Rossmann (1905–84), a former Bauhaus pupil and pioneer of the New Typography in interwar Czechoslovakia, whose work is represented at MoMA. I had just come across mention of Rossmann in Bratislava, where he and the photographer Jaromír Funke taught in the avant-garde School of Applied Arts, known as the Bauhaus of the East. This link was typical of the personal and cultural connections we encountered among many of the cities on our itinerary.

Moravian Gallery collections

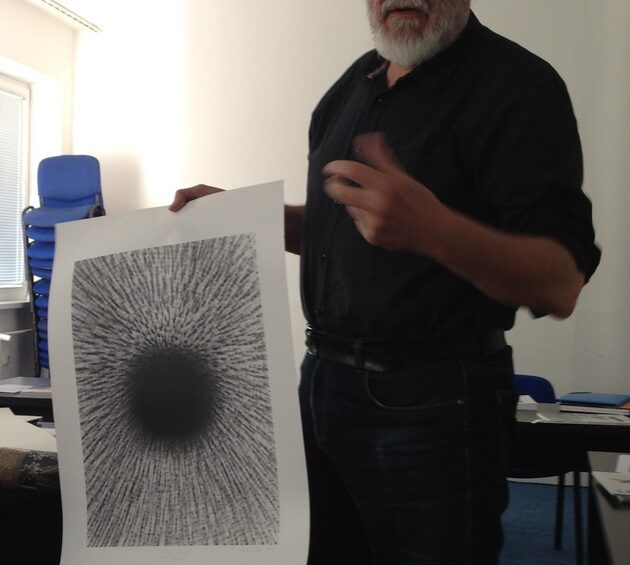

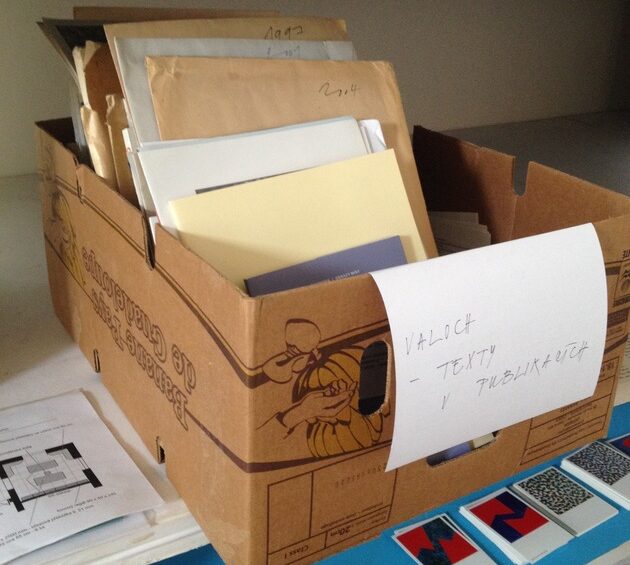

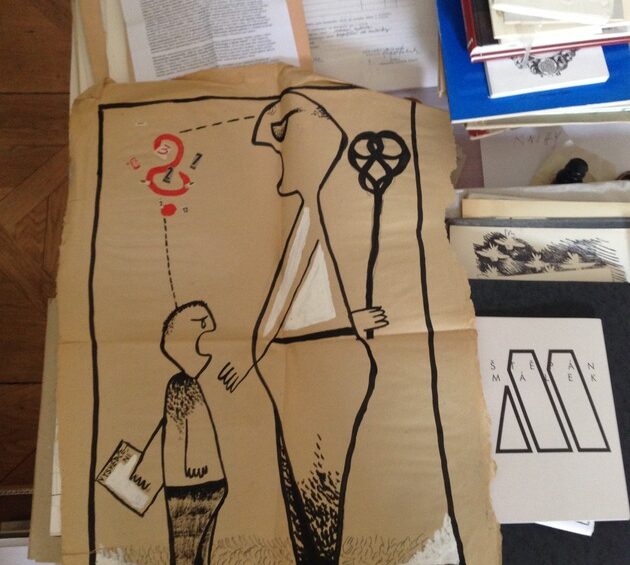

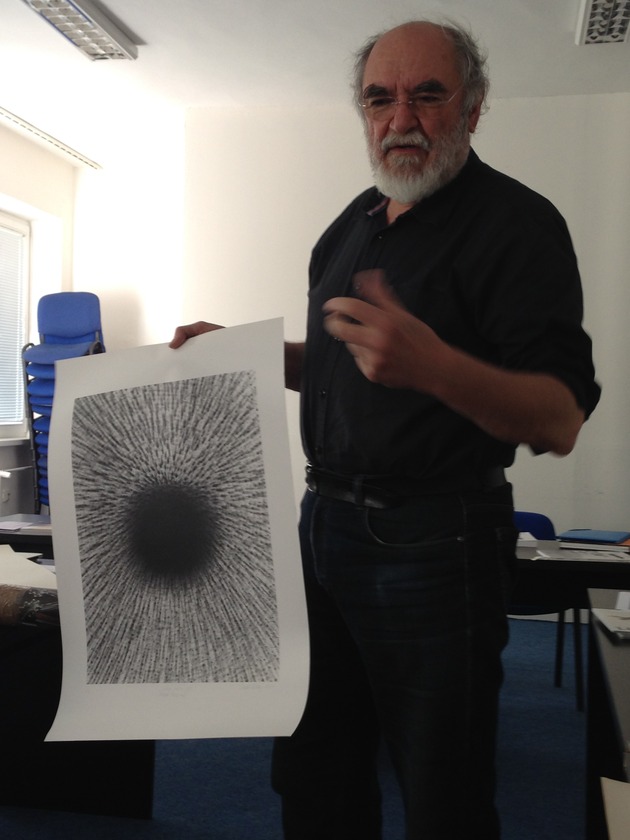

Jiří Valoch

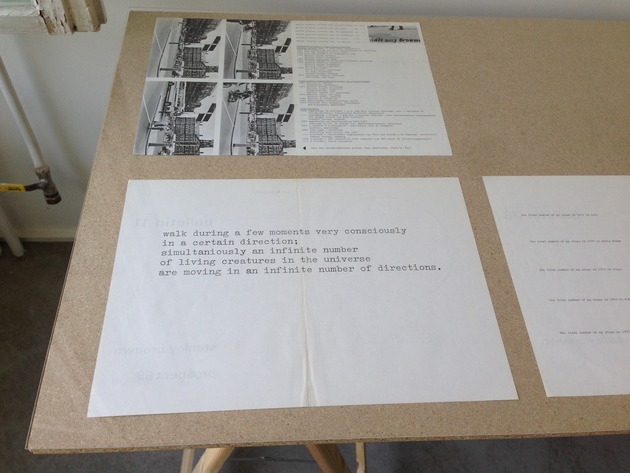

By Jon Hendricks

Dear Jiří Valoch—he so kindly came to greet us at the Moravian Gallery, where he has installed his archives. Jiří is an artist whose work has been in contact with many in the Fluxus group, and there is a good exchange of material in the Valoch archives and in the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Archives now at MoMA. I am certain that many scholars will be making good use of the material so that we can come to a fuller understanding of Valoch’s work.

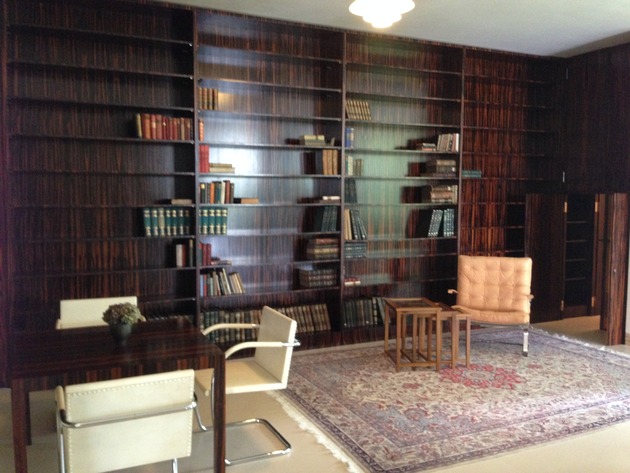

Villa Tugendhat

By Paul Galloway

On May 24 the C-MAP Fluxus group visited the city of Brno in the Czech Republic. In addition to visiting local artists and curators, the team made a pilgrimage to one of the most important modernist houses of the 20th century: Mies van der Rohe’s Villa Tugendhat. Recently reopened after a long and thorough restoration, the Villa Tugendhat is a stunning example of Mies’s explorations in spatial and material design. After the harried first few days of the trip to Eastern Europe, the C-MAP group greatly enjoyed a lengthy tour of the Villa with the site’s director, Iveta Černá, followed by a leisurely exploration of the grounds.

As steward of the Mies van der Rohe Archive, the Museum of Modern Art has an important relationship with all things Mies in the world. MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design played an important supporting role in the long and complex restoration to the Villa Tugendhat, which was undertaken by the city of Brno under the auspices of UNESCO’s World Heritage program. Teams of researchers from Brno spent hundreds of hours at MoMA’s Lily Auchincloss Study Center for Architecture and Design poring over the Museum’s holdings. By the end of the project, a partnership was formed between the Villa’s Study and Documentation Centre and MoMA’s Mies Archive. After the much celebrated reopening of the Villa to the public, curator Juliet Kinchin and I were, in particular, thrilled to visit and cement the lasting friendship with our brilliant colleagues in Brno.

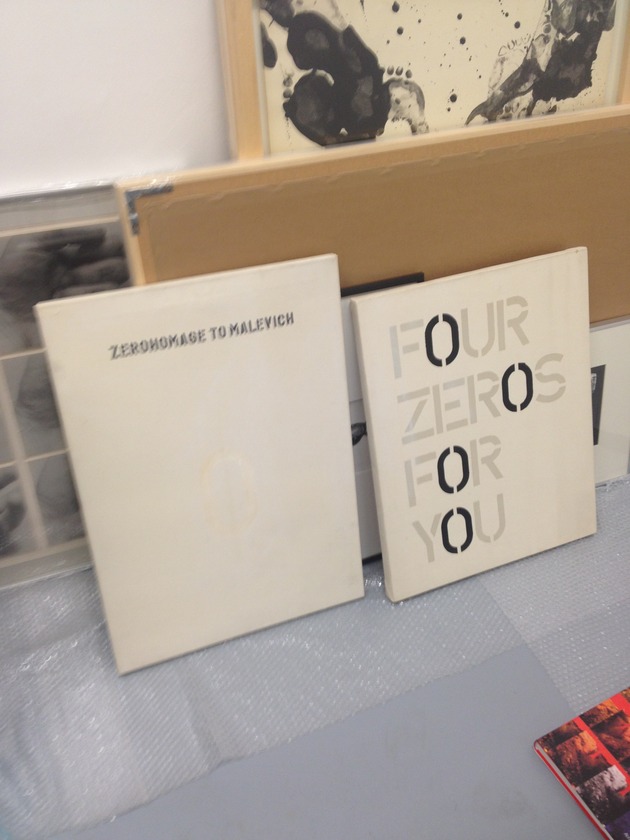

Studio visit with J.H. Kocman

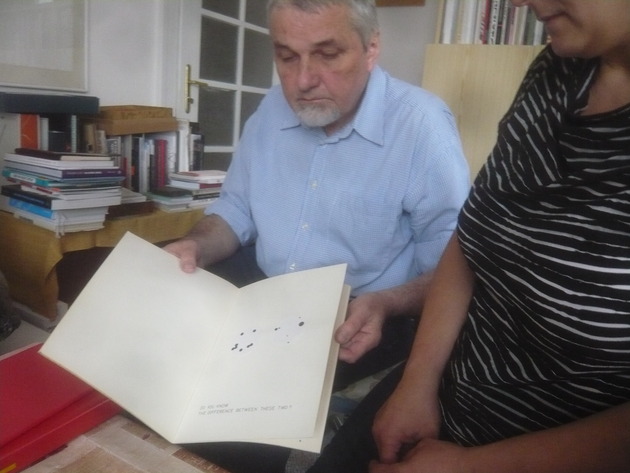

By Milan Hughston

The group visited the home and studio of J.H. Kocman, a prolific book artist and craftsman born in Brno in 1947. Especially after the Prague Spring of 1968, Kocman, like many artists of his generation, had to resort to alternative art practices in order to produce and distribute his works. Primarily, he turned to mail art and rubber stamps to disseminate his work, and in spite of the repressive political climate, he was very productive. The Artists’ Books collection of the MoMA Library contains eleven of his books dating from 1970 to 1995, illustrating a wide range of techniques from stamps to marbling.

Kocman’s studio is filled with evidence of his love and use of paper, particularly marbling. The group admired many of his later books—proof that he has continued to work steadily in the medium for many years.

Studio visit with Jiri Kocman. Video: Magdalena Moskalewicz

4. PRAGUE

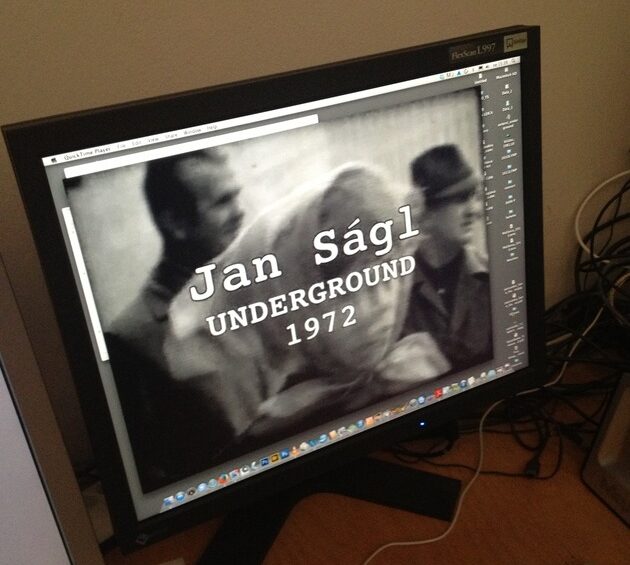

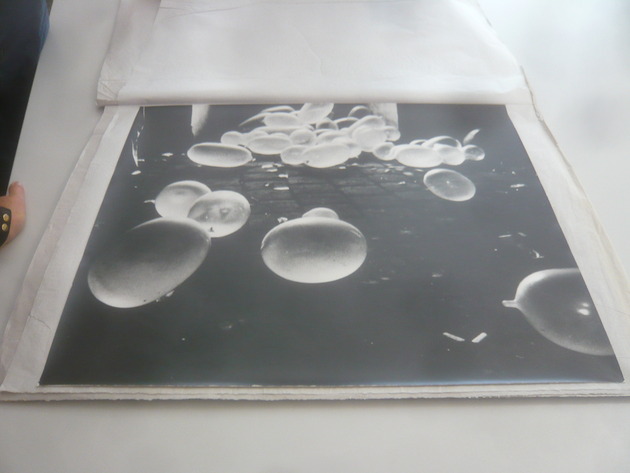

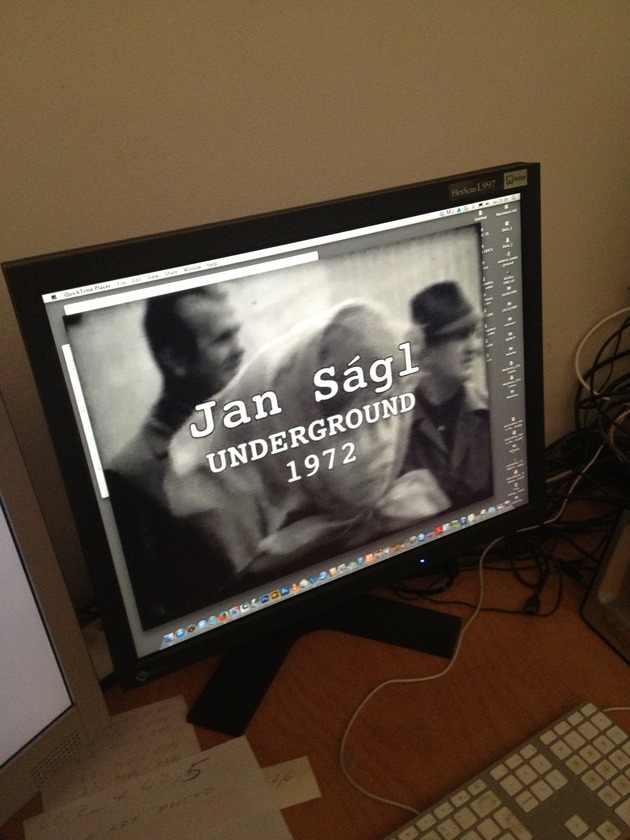

Jan Ságl and Zorka Ságlová

By Michelle Elligott

Jiří Kovanda and Pavlina Morganova

By Jon Hendricks

In Prague, Pavlina Morganova very kindly arranged for Jiří Kovanda to show us his stunning exhibition at the City Gallery of Photography, where we had fun trying to identify artists’ work that he referenced in his own work.

We then walked to the center of Prague with Jiří Kovanda and Pavlina Morganova, and with Pavlina showing us photographs of Jiri’s gesture actions from the mid-1970s, Jiří showed us the exact spots where he had performed them, and we were able to envisage the power of the actions in the context of the surrounding cityscape during a period of restricted freedom in the country. We then all walked to the escalator, and in a way reenacted his 1977 Untitled action. He is a fascinating artist who I knew too little about and I think is someone who has continued to do very strong work up until today.

Pavlina Morganova

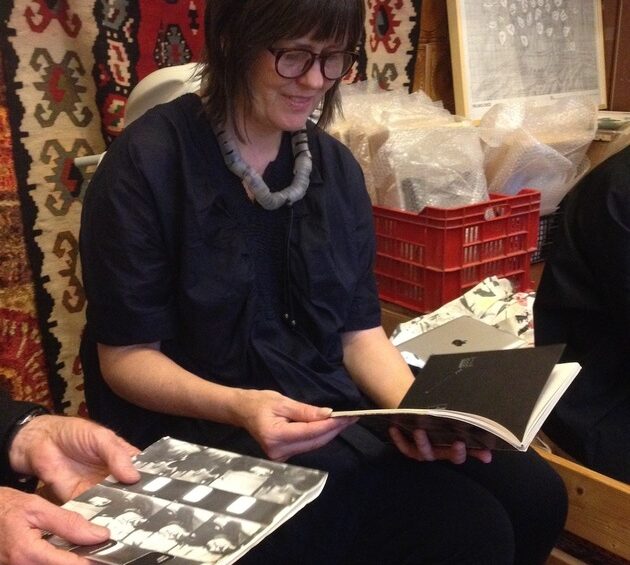

By Jon Hendricks

Pavlina is a brilliant scholar who has dug deeply into the history of Czech action art, and her new book Czech Action Art: Happenings, Actions, Events, Land Art, Body Art and Performance Art behind the Iron Curtain (Prague: Karolinum Press, 2014) is an invaluable reference for all of us who are so interested in Czech art. She was extremely generous with her time, and I know we’re all grateful to her for her kindness.

Meeting Jiří Kovanda

By Roxana Marcoci

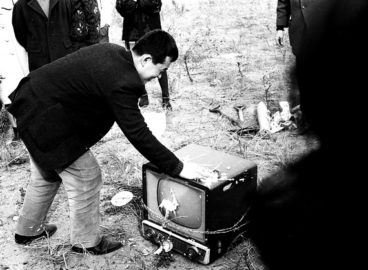

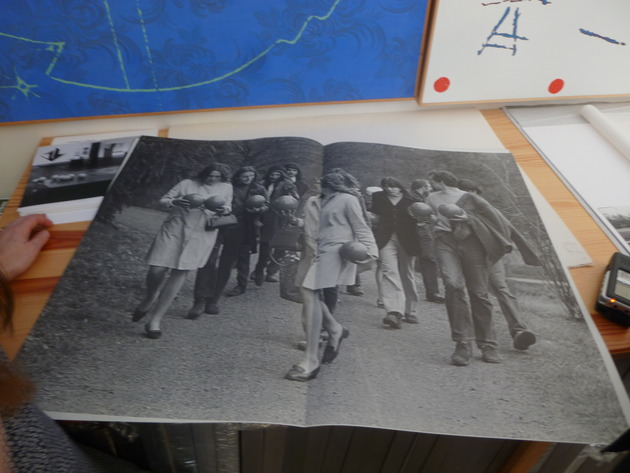

One of the highlights of our C-MAP trip was the time we shared with artist Jiří Kovanda, a leading figure of Czech Actionism, in Prague. Our meeting point was the Prague House of Photography, where we viewed the exhibition Jiří Kovanda Against the Rest of the World, featuring his legendary actions of the 1970s within the context of the history of performance art. Then, we took a walking tour with him and Czech curator Pavlina Morganova around the city to revisit the sites of his public actions.

Kovanda began his career in the radicalized climate of the 1970s (following the 1968 Soviet reoccupation of Czechoslovakia), during a period of forced “normalization” of his country by the Soviet military. Working against the backdrop of political repression, Kovanda asserted his difference amid hardline social conformity by performing minimal yet disruptive gestures. Looking at art as a vehicle for change, Kovanda simply carried water from the river in his cupped hands, releasing it a few meters down the river; he gathered rubbish, and once he had made a pile of it he scattered it all over again; he invited friends to watch him try making friends with a girl; and he walked around Prague, casually touching, in a gentle brushing gesture, passersby—an action that was kindred to Vito Acconci’s “following” pieces of the same period. While walking with Kovanda around Prague, we arrived at one of the city’s subway entrances. Here, the artist allowed us to reenact with him one of his most influential works: Untitled (On an escalator . . . turning around, I look into the eyes of the person standing behind me . . . ), from September 3, 1977). This was a private moment with a generous artist, which left an indelible memory. Analyzing ideas about conformity and malleability, in works such as On an escalator, Kovanda encouraged critical reflection on the relationship between the individual and the ideological forces that shape social reality.

Walk Through Prague with Jiří Kovanda and Pavlina Morganova

Museum Kampa

Kveta Pacovska

By Milan Hughston

When visiting the Moravian Gallery in Brno, we were encouraged by Marta Sylvestrova to meet with the Prague-based artist and illustrator Kveta Pacovska, who is married to Milan Grygar. Pacovska has enjoyed a long career as one of former Czechoslavakia’s most recognized and published artists of children’s books. In fact, one of our hosts, Tomas Pospiszyl, said that all children of a certain age in Slovakia immediately recognize the whimsical yet instructional images that Pacovska has been producing for forty years.

When in Prague the next day after visiting Brno, I took a taxi to her studio in a residential suburb of Prague and found her to be an enchanting, modest, and hard-working artist, still going strong at the age of 86. Each of her many books takes an often unique approach in teaching children how to count, spell, and recognize shapes. She is too modest to note that her books continue to sell well internationally and that she was awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Award in 1992, the premier honor for writers and illustrators of children’s books.

The rest of the CMAP group had the privilege of meeting her when we visited Milan Grygar’s studio later that day.

Milan Grygar’s Acoustic Drawings

Walk through Prague Art Galleries

Views of Prague

5. WROCŁAW

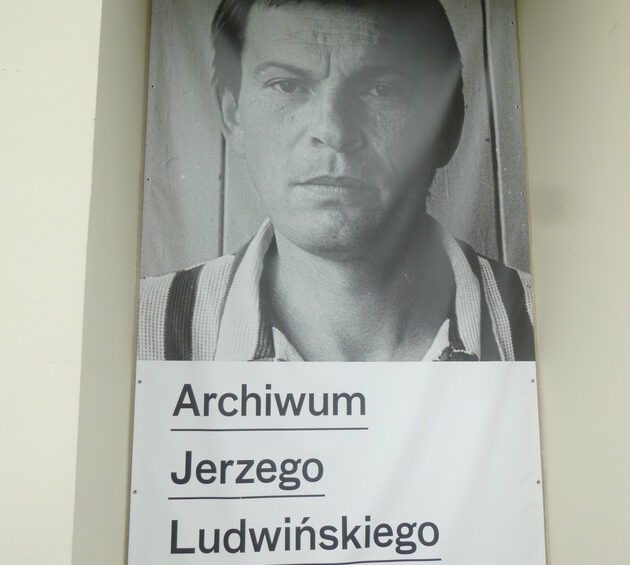

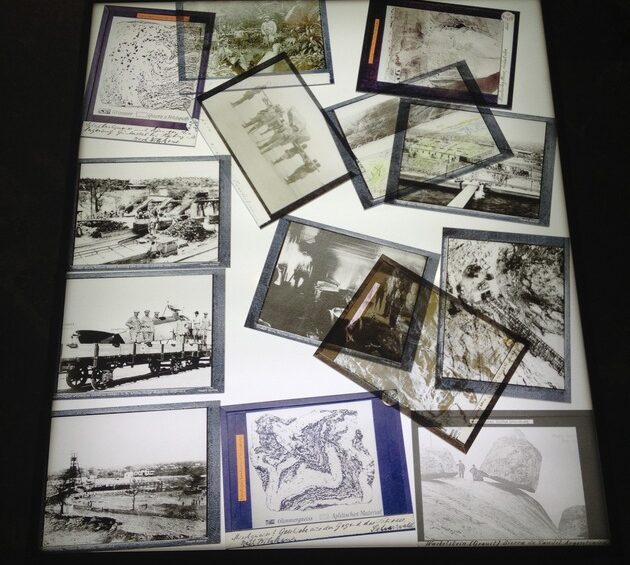

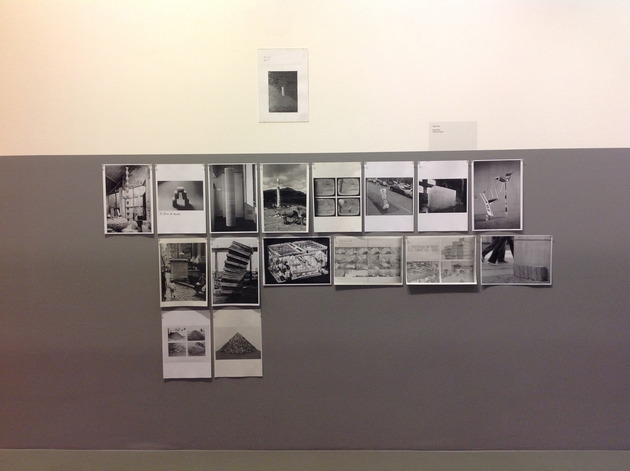

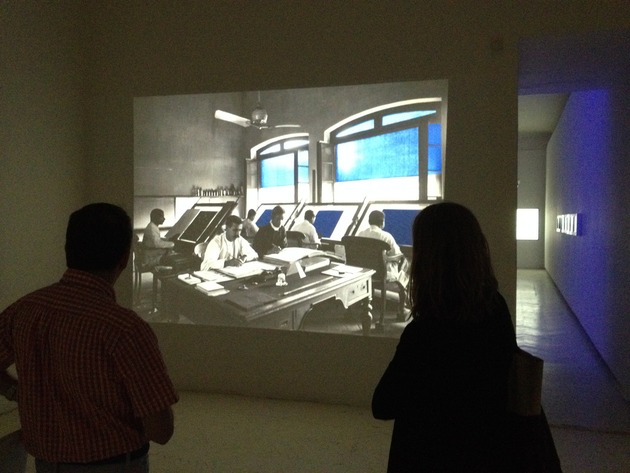

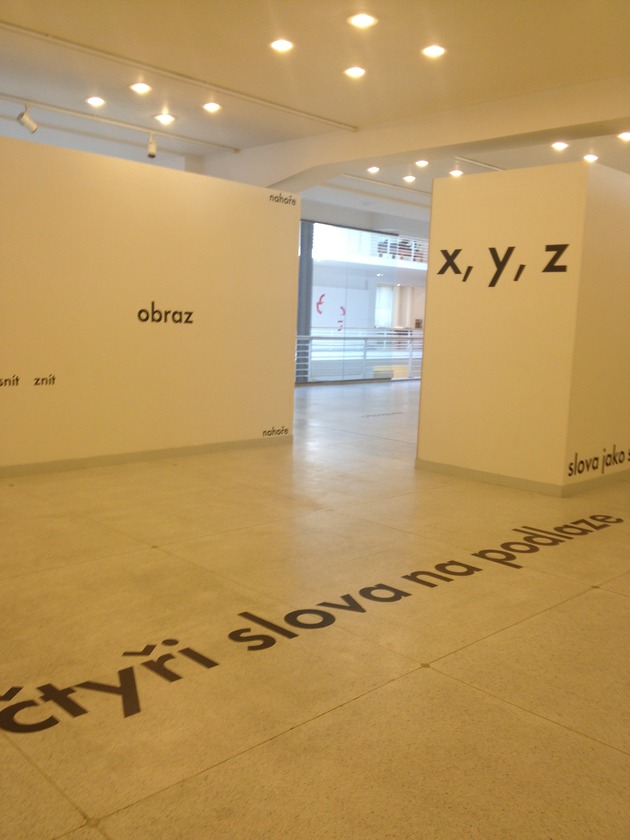

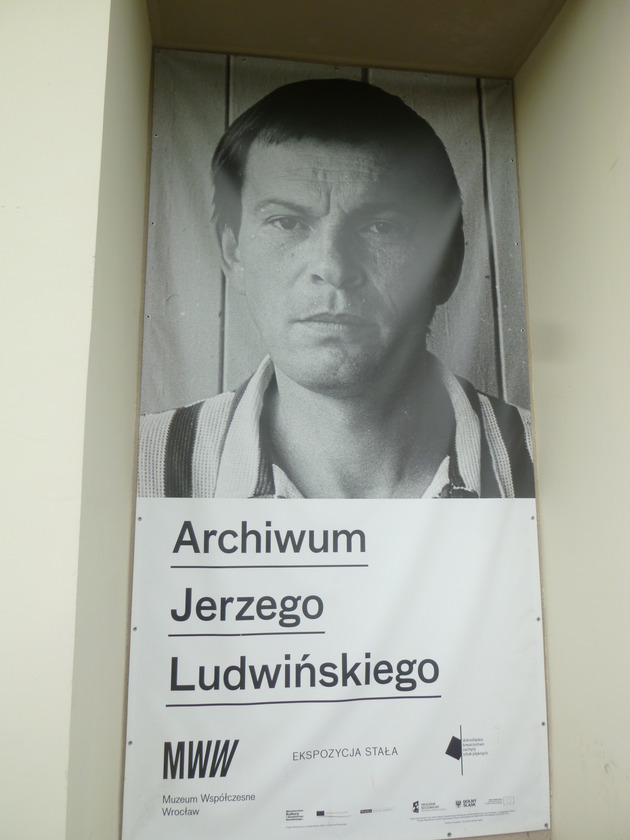

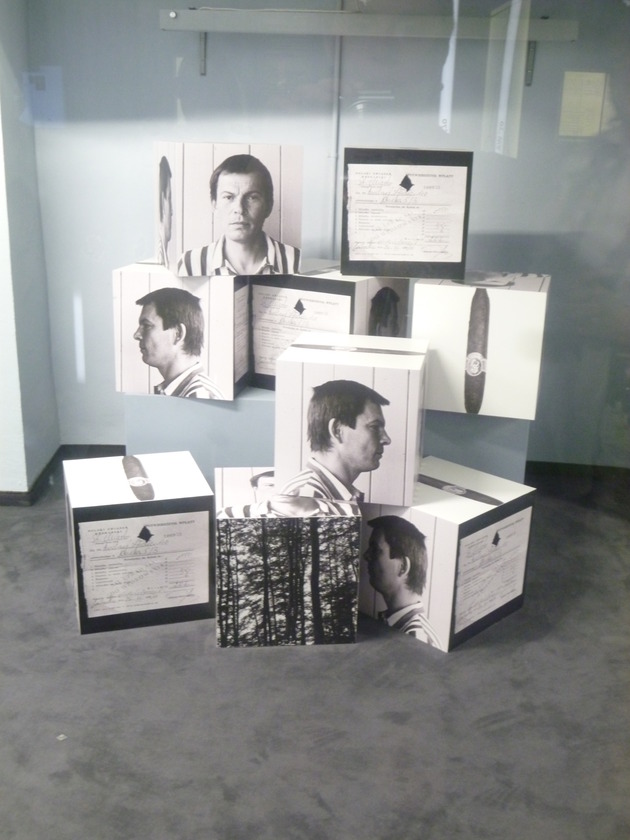

Muzeum Współczesne-Ludwiński Archive

By Michelle Elligott

Muzeum Współczesne

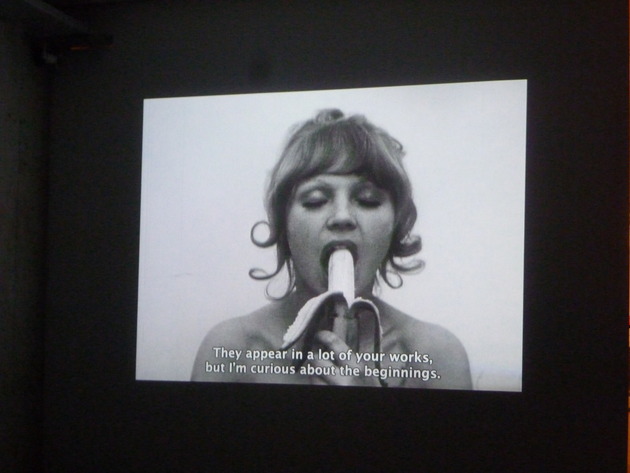

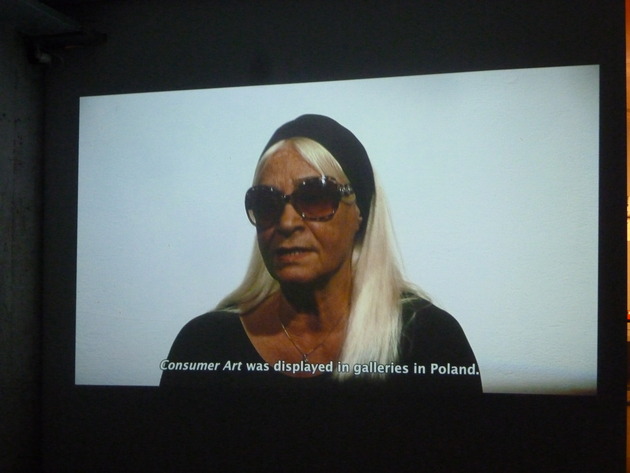

Meeting Natalia LL

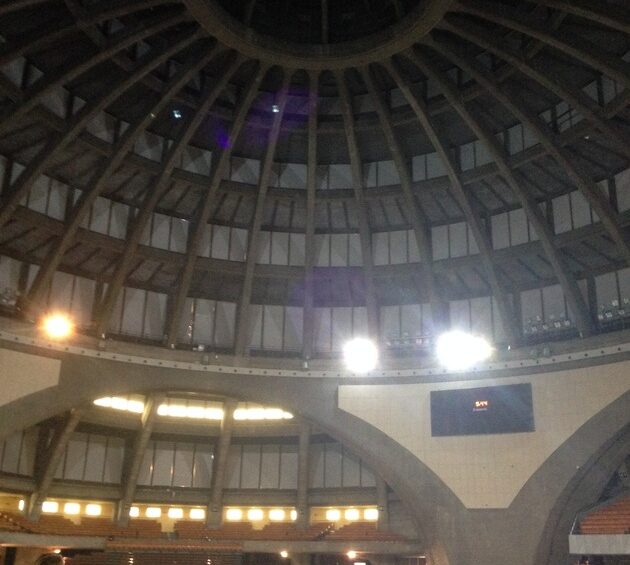

Olympic Stadium

By Milan Hughston

It is often a good idea to listen to your taxi driver when visiting a city you are not familiar with, especially if you are interested in modern architecture. As we were departing Wroclaw for Berlin, our driver, knowing of our interest in the Centennial Hall, suggested that we visit the Olympic Stadium in Wroclaw. The stadium was built in 1926–1928 by German architect Richard Konwiarz (1883–1960) as Schleisierkampfbahn (Silesian Arena) when Wroclaw, then called Breslau, was part of Germany. Like many other visitors, we were confounded by its name, since no official Olympics took place in Breslau. However, it is acknowledged that it could have been planned as a venue for the Summer 1936 Olympic Games held in Berlin.

Konwiarz’s design was awarded a bronze medal in the art competitions held during the Summer 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Although it has seen constant use as a motor speedway and soccer stadium, it still retains its essential character and modernist feel.

Architecture in Wrocław/Breslau

By Juliet Kinchin

Less well known than the Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart is the Deutsche Werkbund’s comparable initiative known as Wohnungs- und Werkraumausstellung (Workplace and House Exhibition, WUWA), carried out in 1929, when Wrocław (then Breslau) was still part of Germany. The posters and graphic identity created by Johannes Mohlzahn for this event are among of the highlights of MoMA’s New Typography collection. The exhibition took the form of a housing development made up of functional “type” houses by a group of modernist architects. One of the most interesting buildings in the complex was Hans Scharoun’s house for singles and young couples, which now serves as a hotel. Noting our interest in modernist architecture, our driver took us on a short detour to the somewhat derelict “Olympic” Stadium built in 1926–28, then extended from 1935–39 as the Hermann Goring Stadion. Before leaving Wroclaw, we also paid homage to a pioneering work of modern engineering and architecture, Max Berg’s Centennial Hall of 1911–13 (now known as the Hala Ludowa, or People’s Hall). The importance of the hall has been recognized and it is now a UNESCO site. This massive recreational and performance space was constructed of reinforced concrete, providing a powerful example of the potential of this material to enclose and span huge spaces without the need for supporting columns. It survived the devastation of World War Two, becoming the setting in 1945 for the International Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace, which was attended by György Lukacs, Pablo Picasso, Louis Aragon, Paul Eluard and Julian Huxley, among others. Perhaps MoMA’s founding director Alfred Barr was there also, since he acquired a printed textile square designed by Picasso to commemorate this event. Barr later donated the piece to the Museum.

Centennial Hall

6. BERLIN

Fahrbereitschaft, Haubrok Collection

By Michelle Elligott

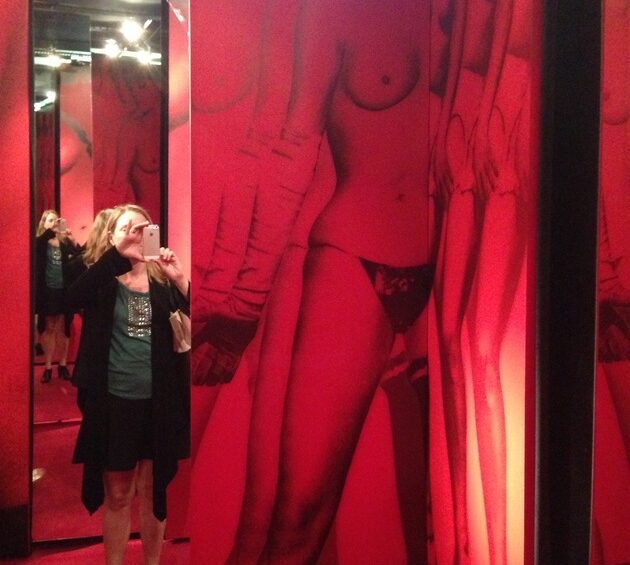

Dorothy Iannone

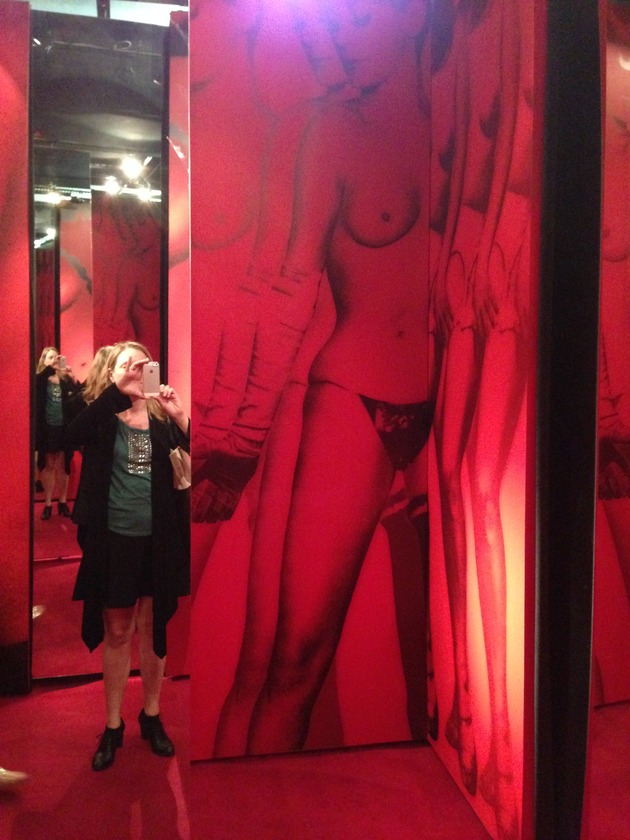

By Jon Hendricks

I had the opportunity to see Dorothy Iannone’s major retrospective at the Berlinische Gallery days before it closed, and also to visit her in her studio. She is a dynamic and bold artist whose work I’ve admired for many years, and her retrospective gave a chance for many to become more familiar with her work over a long career. She is a political artist in the best sense of the word who spares no one. She is bitingly honest and direct. Her retrospective will be traveling to Zurich later this summer (Migrosmuseum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich, August 30–November 19, 2014), so many more will have a chance to see it there. It was strange to be in her home with the usual cacophony of work momentarily stilled by the retrospective, but she was there and made up for any lack of the work’s presence, as she was present, and her voice and ideas are like her work.

Bazon Brock

By Jon Hendricks

Bazon Brock is an artist who I am familiar with only by name, by association, and by traces of his work. He was part of 24 Stunden at the Galerie Parnass (Wuppertal, 1965) and was also part of the legendary Aachen, July 20, 1964 events titled Actions, Agit-Pop, De-Coll/age, Happenings, Events, L’Autrisme, Art Total, Re-Fluxus, which included works by Eric Andersen, Joseph Beuys, Stanley Brouwn, Henning Christiansen, Robert Filliou, Ludwig Gosewitz, Arthur Koepcke, Tomas Schmit, Ben Vautier, Wolf Vostell, and Emmett Williams, which is most famous in our consciousness for a photograph of Joseph Beuys with a bloody nose, holding his arm up, and with the other hand holding an assemblage with a crucifix. Brock was fascinating to talk with and had very different points of view about Fluxus and the period than I have, and I hope that we will have an opportunity to have him visit the Museum in New York to discuss his thoughts further.

Seen at Berlin Biennale