While going through MoMA’s Czech holdings during my Fulbright Research Fellowship at the Museum, I came across a surprising finding: the first Czech objects ever acquired by MoMA were a glass tumbler and two bowls designed by a young student, Věra Lišková (1924–1979) circa 1947, when Czechoslovakia was still part of the industrialized Western world. In the 1940s, Lišková’s set was highly esteemed. Its story, partially linked to MoMA, reflects the brutal changes that took place in Czechoslovakia in the 1950s.

Directly after World War II, Czech businesses were required to implement two-year plans drawn up with respect for the diversity of their ownership and the autonomy of their management. After the Communist putsch of 1948, strict centralization was imposed, and irrational five-year plans were introduced. This situation ruined the design production and distribution cycle and Czechoslovakia quickly lost its position as a developed industrial economy. Lišková’s set of glasses in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art remains a testament to the lost hopes of Czech industrial design of the period.

A student’s design: paving the new way

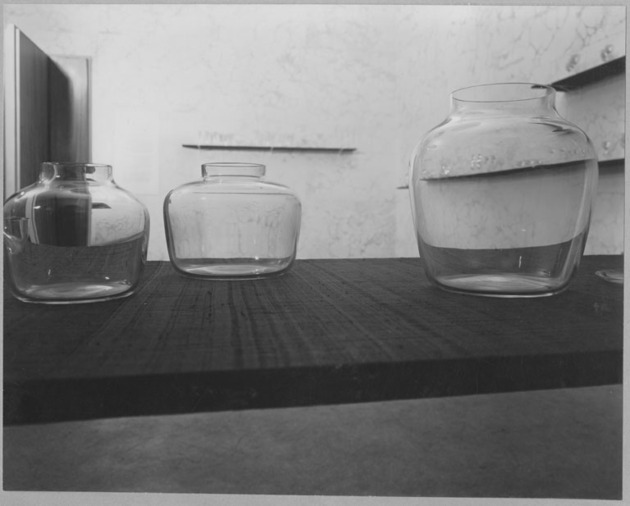

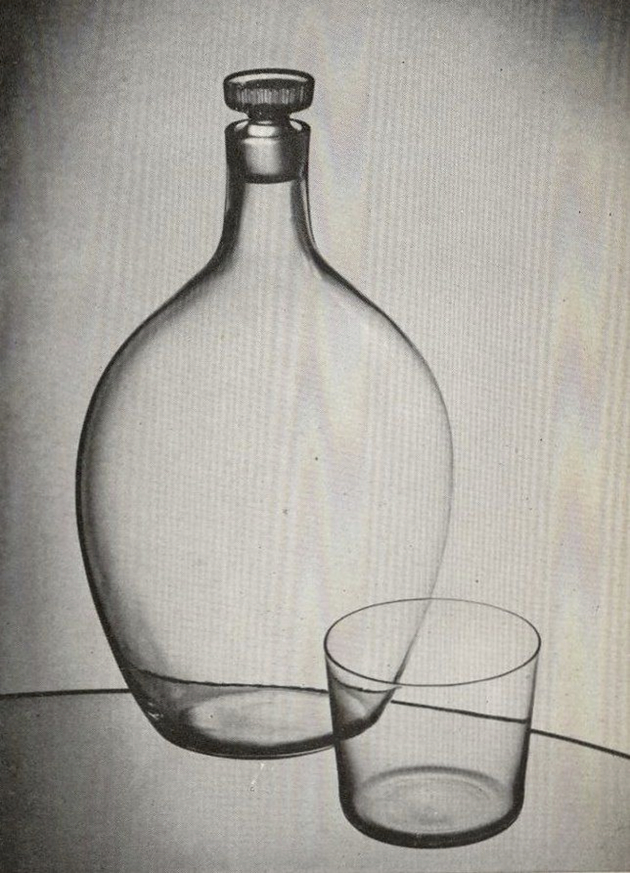

Věra Lišková’s set, that the tumblr from MoMA’s collection belonged to, was produced by the Lobmeyr company in its glassworks in Kamenický Šenov in Northern Bohemia. The artist was at that time a talented student at the Academy of Arts, Design and Architecture in Prague. She designed the set during her internship at Lobmeyr under the supervision of Stephan Rath, the factory’s manager. The set was produced as an experimental, hand-blown prototype in 1947 and was awarded a prize by the Czech ministry of industry and commerce the following year. According to the jury, the set represented exceptionally good design, “paving the new way for postwar industrial glass.”

Why was the set so highly praised? Its simple, pragmatic forms and perfect execution corresponded well with pre-war criteria for functionalist glass design: harmony of function and form, unembellished form and surface, transparency, superior material and execution as well as affordable price. These standards became vital requirements in the country’s new political and social context. In the aftermath of the war, Czechoslovakia found itself in the zone of Soviet influence and had undergone changes of the political and economical systems. Czechoslovakia’s partially nationalized economy was driven by two-year plans, the goal of which was to build a national democratic state for all except the German population. The appeal for democracy, universal accessibility, and modesty was omnipresent. Democratizing glass design meant rejecting luxurious ornamentation, making glass cheaper and widely available. These goals were widely debated, as richly decorated glass (cut, engraved, painted) was the pride of many manufacturers, including Lobmeyr.

Lišková’s set not only met those standards but offered something more. Her work’s ascetic design was neither strict nor austere but had human tenderness and brittle fragility in its proportions. These characteristics answered the call for forms of beauty that could heal humanity in the wake war, make everyday reality more humane, and imbue the vernacular with the sublime. Mass production, it was believed, should be driven by the beauty of its time.

Lišková’s set reveals the new alliance of craft and industrial production. Reflecting an industrial aesthetic, the set was hand blown and ready for mass production, but its singularity was achieved through Lobmeyr’s master craftsmanship. The company’s superb workmanship resulted in products that displayed the industrial aesthetic at its highest level.

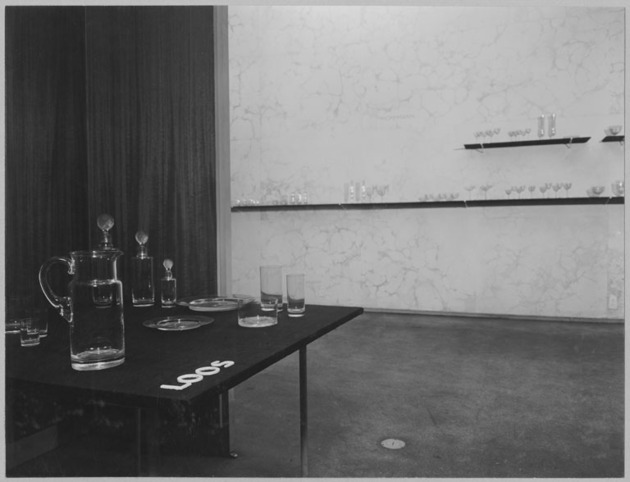

Continuity with Loos

J. & L. Lobmeyr, founded in 1823 in Vienna, was known for its luxurious, unique glass objects and especially for richly decorated glass. Lišková’s set belongs to the company’s clean line, designed specifically by architects in the 20th century. Lobmeyr’s collaboration with architects was initiated by Stephan Rath, an Austrian designer who acquired the company in 1917 and the following year established Lobmeyr’s branch in Czechoslovakia —where the company’s plants had been located even earlier— in the small northern city of Kamenický Šenov. Rath commissioned Adolf Loos to design his celebrated bar set in 1929. According to one source, Loos made his preliminary sketch for the set while sitting in a café.1Václav Cigler, interview with the author 2010. Cigler, an artist and designer who studied with Věra Lišková, learned this from Josef Kaplický, their teacher on the Academy of Arts, Design and Architecture. Josef Kaplický was familiar with František Müller and Milada Müllerová, for whom Loos designed the Villa Müller in Prague. The original drawing features a series of cylinders of different heights and volumes. During production, the crystallic diamond-cut was added to the bottom of the vessels because Rath, who supervised the execution, worried that the undersides would get scratched during use. The Loos drinking set represents a revolutionary milestone in I modern drinking glass design. Departing from the tradition of providing differentiated and adorned shapes specific to every piece, Loos’s set presents a system of single geometric forms in a variety of sizes and proportions. It is the pride of glass collections the world over, inspiring designers as well as artists.2For example, Mathias Poledna in his film Double Old Fashioned, 2009.

A similar concept of pure, open cylinders would appear 20 years later in Věra Lišková’s set, produced in close collaboration with Rath. It became the sign of refreshed continuity in Lobmeyr´s unornamented production line.

Showing at MoMA

The exhibition of Lobmeyr glass at MoMA in 1949 reflects the complicated position of the Lobmeyr company in Czechoslovakia after World War II. Rath, who spent the war years in Vienna, returned to Prague at the war’s end in order to help train Czech glass artists and assure the continuity of his factory in Kamenický Šenov. He invited craftsmen from Vienna to join him and collaborated closely with art schools. The expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia in 1945 drained the northern Bohemian glass industry of workers, designers, and teachers, yet Rath’s plants quickly resumed production of admirable, high-quality glass.

After 1945 Lobmeyr went through the first stage of nationalization: special commissions from the Czech state included a gift for Eleanor Roosevelt. Rath,still the company’s manager, exported Lobmeyr products to the U.S. through A. J. Van Dugteren, a salesman of European goods in America. After the Communist putsch in Czechoslovakia in February 1948, the Lobmeyr factories went through a second phase of nationalization. As a result, Rath lost his post as manager and became the company’s art director and adviser. Official commissions took the form of goblets for Stalin, MaoTse-Tung, and Haile Selassi, the emperor of Ethiopia.

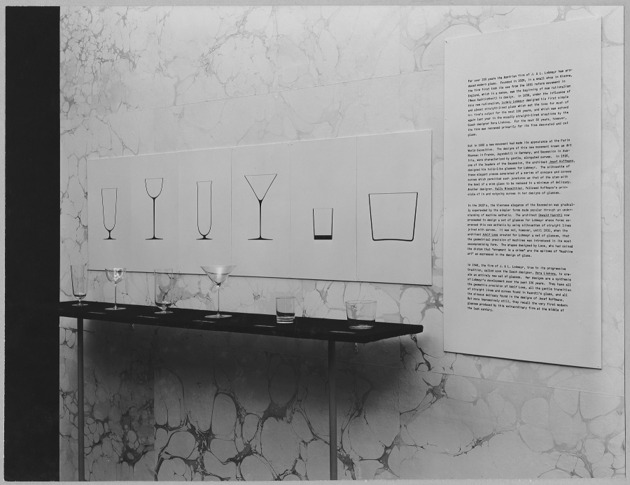

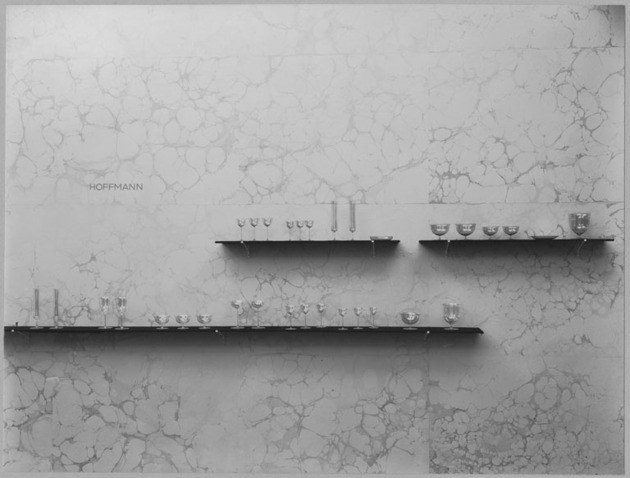

Van Dugteren assisted with the preparations of the Lobmeyr exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art. Titled Lobmeyr Glass, the show opened in April 1949. Philip Johnson, director of the Museum’s Department of Architecture and Design, selected the works and conceived the exhibition’s design. The press release describes the nearly geometric precision of certain objects’ simple, unadorned shapes and names three designers: the architects Josef Hoffmann and Adolf Loos, and “the young designer Věra Lišková,” the creator of “beautiful shapes” that “have never before been shown publicly.” That the unknown Lišková was singled out in the exhibition’s marketing materials—more than ten respected glass designers were represented in the show— is an indication of Johnson’s admiration for her work.

Johnson employed gold-veined marbleized wallpaper and mahogany furniture in the exhibition. The display underscored the luxurious side of Lobmeyr’s production, while the majority of the objects embodied the modern, simple, geometric side. Interestingly, Johnson’s display was in harmony with the most sumptuous of all of Lobmeyr’s exhibitions, held the following year in the most magnificent Baroque palace in Prague. The marble and rare wood interior of Velkopřevorský palace, the former residence of the catholic Order of Knights of Malta, which had been confiscated, provided the space for Lobmeyr to promote itself as a luxury enterprise during Czechoslovakia’s transition to hard-line Communism.

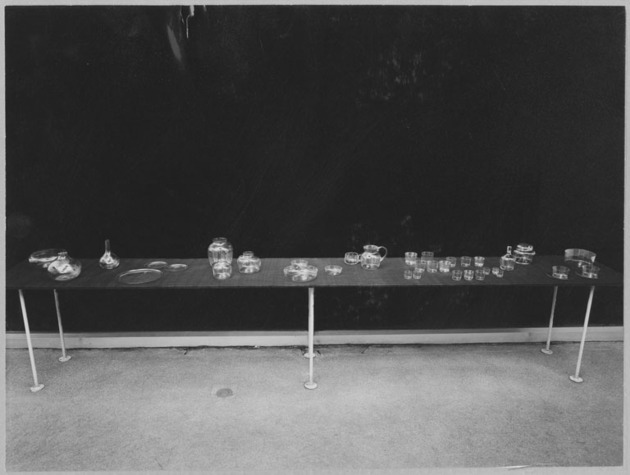

Lobmeyr Glass traveled through the United States, winning widespread recognition for the Lobmeyr brand. In 1952¬¬–53, Lobmeyr products, including the sets designed by Lišková and Loos, were donated to the Museum. About this time, Rath left Czechoslovakia for his company’s main offices in Vienna, and the factory in Kamenicky Šenov became part of Borské sklo National Corporation, the huge, centralized glassmaking enterprise. In Vienna, Rath continued to manage Lobmeyr with the aid of his son, and within a few years the company’s high-quality production was reestablished in Austrian plants.

Educating American Audience

Lišková’s set captured the attention of Edgar Kaufmann Jr., the director of the Museum’s Department of Industrial Design and the organizer of a series of exhibitions in which he attempted to educate Americain audience on how to furnish the home in a modern way. Kaufmann was also the author, in 1950, of the influential book-brochure What Is Modern Design?, whose authoritarian text became mandatory for the perception of the 1950s’ design. Lišková’s set is among the book’s few examples of glassware. It readily met the author’s requirements of efficiency and intrinsic beauty, the latter term understood, in the sense put forward by Thomas Aquinas, as combining integrity, clarity and harmony. In the text, Kaufmann shows his familiarity with contemporary Czech design through his recommendation of the magazine Tvar (Shape) and praise for the quality of the country’s glass and textile production.

Lišková’s set was included in the 1958 edition of Masters of Modern Art, a book of highlights from MoMA’s collection.3Alfred H. Barr Jr., ed., Masters of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1958). Lišková ´s set is illustrated in the chapter by Arthur Drexler, “Architecture and Design,“ p. 226. In his text, Arthur Drexler, who had succeeded Philip Johnson as the director of the Department of Architecture and Design, wrote that the Museum’s rigorous criteria for acquiring design objects made MoMA the world’s leading institution in contemporary design. Selected by Drexler from among 900 design objects in MoMA’s collection, Lišková’s set was represented by the bowl and tumbler in outstanding photographs by Herbert Matter.

All votes for Lišková/Lobmeyr

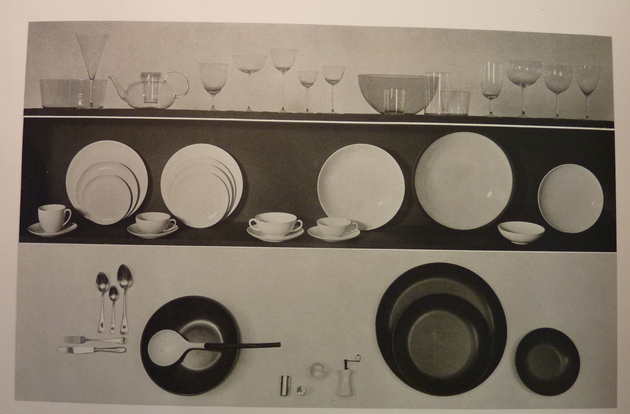

Lišková´s set also had an exceptional position in the now-legendary exhibition Glass 59, the first-ever international juried presentation of contemporary table glass, organized by The Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York.

The show of glassware produced between 1955 and 1959 attracted 1,814 submissions from 23 countries. Each of the five jury members was instructed to select 100 objects and to choose three among them as exemplars of the criteria on which their selections were based. Lišková’s set appears in the defining trio chosen by Gio Ponti, the Italian architect and designer, editor of Domus, director of the Triennale di Milano, and most prominent member of the jury. In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Ponti admits that he had felt an urge to steal the barbaric vase by Modema Muníz and that “the honesty complex” had made him choose the simple, true, and pure form of Lobmeyr glass as a counterbalance to the dramatic, complex form of Muníz’s work.

In fact, Lišková’s set was chosen by all members of the jury. Not only Ponti and Kaufmann, who were familiar with Lišková’s work, but also Leslie Cheek, director of the Virginia Museum of Art and editor of House Beautiful, known for his inclination toward the decorative; writer Russell Lynes, with his literary interests; and the woodworker and furniture designer George Nakashima, with his appreciation of craftsmanship and proportion. Only seven other objects among the 800 included in the final selection obtained the maximum five votes of approval.

It is possible that the jury was seduced not only by Lišková’s design but also by the fame of the Lobmeyr brand name. In the catalogue, the set is included in the brief chapter on Austria, whereas other objects by Lišková—a dining set and a glass frog —were included in the large chapter on Czechoslovakia. Those “Czech” objects, molded in a much heavier glass than the fragile Lobmeyr set, typify glass design of the following decade and attest to Lišková’s talent for grasping and expressing the changing spirit of the time.

The double presence of Lišková’s work in the catalogue of Glass 59 sparked a strong reaction in the Czech press. Curator and historian Karel Hetteš, an ardent supporter of the postwar revival of Czechoslovakia’s glass industry and a champion in his many published writings of Lišková’s original set, accused the Lobmeyr company of unfair competition for presenting work conceived 10 years earlier. In fact, Lišková had modified her original design very slightly in 1958. For Glass 59, the set was produced in an updated, timeless form and was marketed at the reasonable price of $42 for a dozen pieces. Hetteš also sharply criticized the Czech glass industry for failing to introduce Lišková’s famous set on the domestic and foreign markets. He considered the work a source of national pride that was not to be shared or confused with the Lobmeyr brand. The set was seen as the exemplary prototype for socialist industry, whose ideal of “property of the people” violated copyright, trampled on individual merit, and broke with the basic democratic rules of respect for privacy and the individual.

However, the official Czechoslovak export agency Glass Export recognized the value of the Lobmeyr name and opportunistically decided to blend the private brand name and socialist state export interests. “Lobmeyr” was officially attached, in the 1950s, to the name of the national glassworks in Kamenický Šenov, calling the plant Borské sklo, branch Lobmeyr. Simultaneously with Hetteš’s appraisal, came Rath’s international suit. The former owner sued and ultimately won a long legal battle to regain control over the name of his company.

Meanwhile, Lišková attempted to collaborate with the nationalized Czech glassworks, but her designs, as well as those of other students preparing to enter the glass industry, never went beyond drawings and prototypes. Factory managers tied to five-year plans, oriented to the huge Soviet market, and measuring success in terms of quantity, showed no interest in innovative design. During the Cold War, in order to showcase the high achievements of the Czech glass industry, the state occasionally commissioned prototypes for display in foreign exhibitions, but these were never realized in mass production. At the end of the 1950s, a frustrated Lišková, along with many of her colleagues, turned to experimental glass sculpture.

- 1Václav Cigler, interview with the author 2010. Cigler, an artist and designer who studied with Věra Lišková, learned this from Josef Kaplický, their teacher on the Academy of Arts, Design and Architecture. Josef Kaplický was familiar with František Müller and Milada Müllerová, for whom Loos designed the Villa Müller in Prague.

- 2For example, Mathias Poledna in his film Double Old Fashioned, 2009.

- 3Alfred H. Barr Jr., ed., Masters of Modern Art (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1958). Lišková ´s set is illustrated in the chapter by Arthur Drexler, “Architecture and Design,“ p. 226.