Renowned Chilean art critic, Adriana Valdés, visited MoMA to talk about the works of Eugenio Dittborn. During her visit, she not only thoroughly discussed the importance and semantic weight of Dittborn’s Airmail Paintings, but she also described the peculiarities of the Chilean art scene, one that Dittborn himself has identified as “a sort of small and ridiculous battlefield.”

This presentation focuses on Eugenio Dittborn’s works from the seventies to the present, while at the same time trying to address the political, social, and artistic tensions within the context in which they were produced.

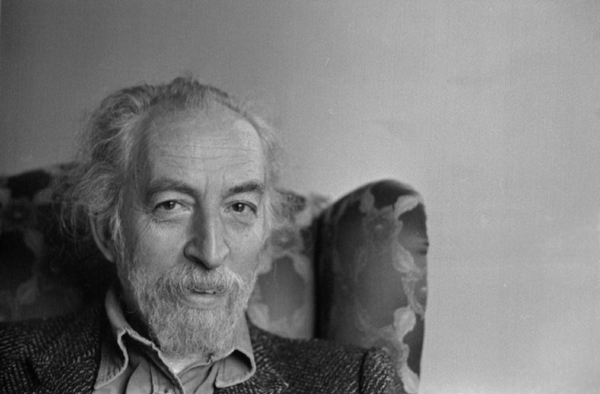

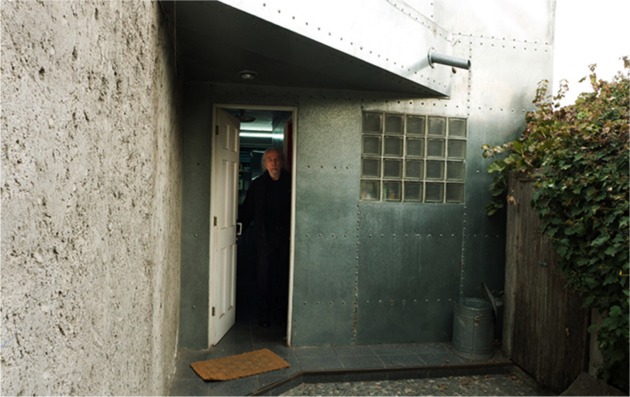

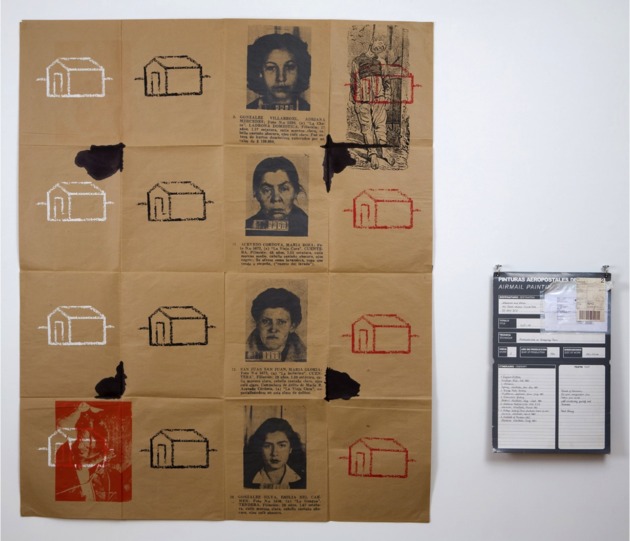

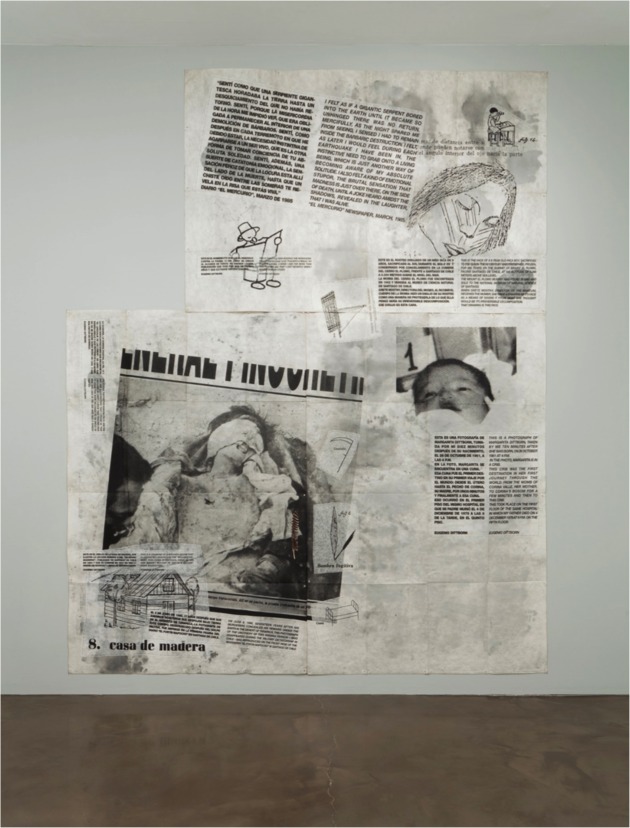

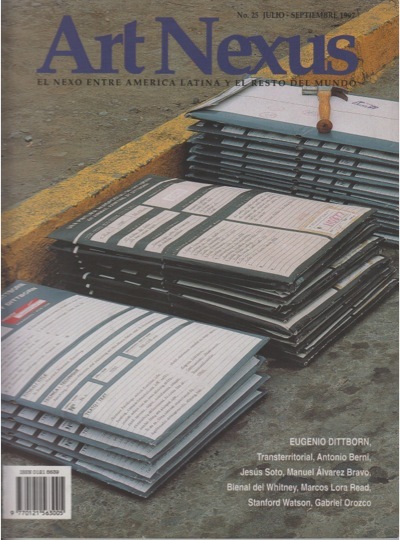

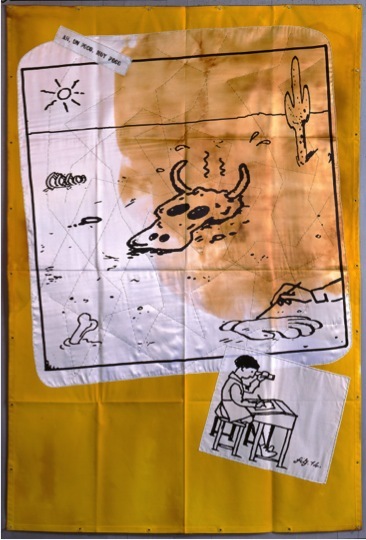

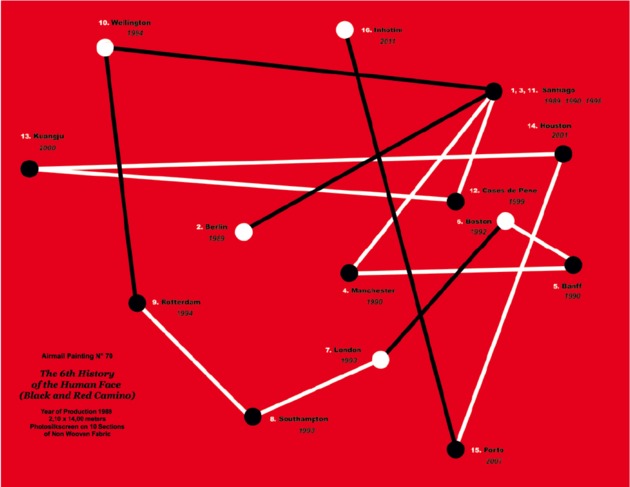

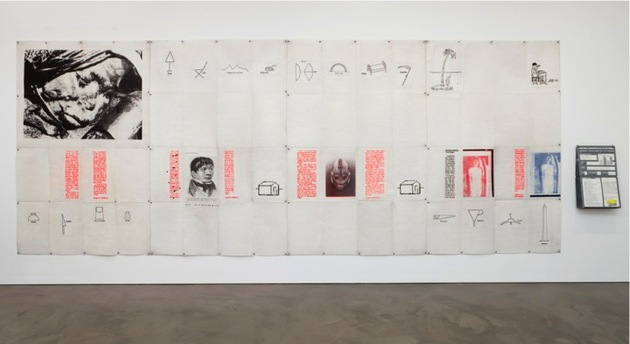

First, I’d like to introduce Dittborn to you with a few “headlines”. I’ve borrowed them from a fairly recent article that appeared in The Economist1See https://www.economist.com/news/2011/01/19/el-genio-dittborn. A longer version of this article appeared in Sarah Thornton, Thirty-three Artists in Three Acts (London: Norton & Norton, 2014). entitled “Un Genio Dittborn,”2In Spanish the artist’s first name, Eugenio, sounds extremely similar to the phrase “un genio,” which translates “a genius.” in which he is described as an “escape artist.” There, he is quoted as saying: “I invented these folded paintings to get out from this place, to be in the world.” “This place” is Santiago, Chile, which he describes as “a sort of small and ridiculous battlefield.” He refers to his windowless studio as “a bunker,” and he keeps all his “sources” and his works meticulously and systematically organized there. His “sources” are really old magazines, “popular culture and prison culture,” he says, as well as old books on drawing techniques. Here, to show you what they look like, are two Airmail Paintings,3Dittborn has been producing his Airmail Paintings for more than three decades. Each of them is folded and placed in a specially prepared envelope, and each of them travels the world on its own, particular itinerary. For more information, see Dittborn, Eugenio, Mundana: 24 pinturas aeropostales en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santiago de Chile Santiago (Chile: Pública Editores, 1998). [use the arrows below to scroll through the images] one from his first period, and one from his last (note the changes in scale and in materials).

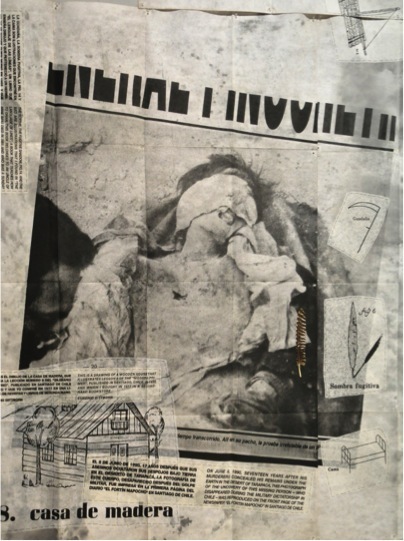

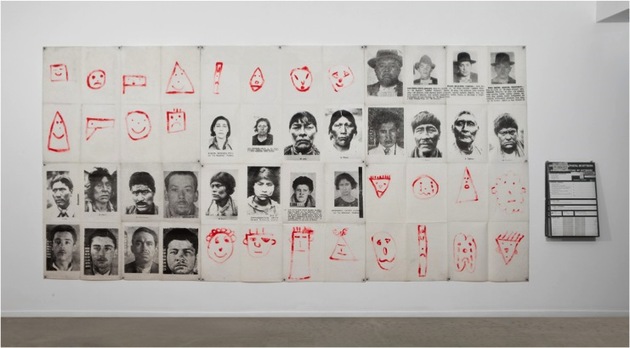

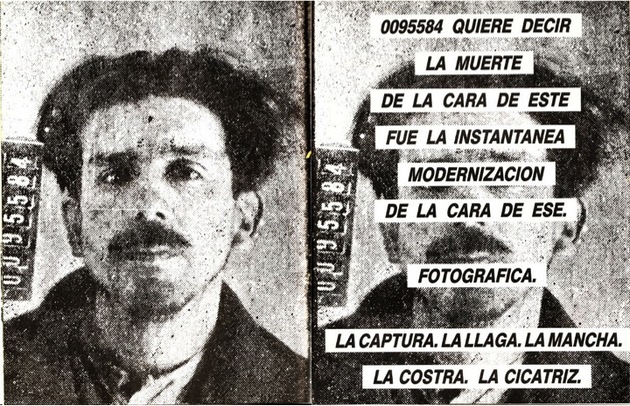

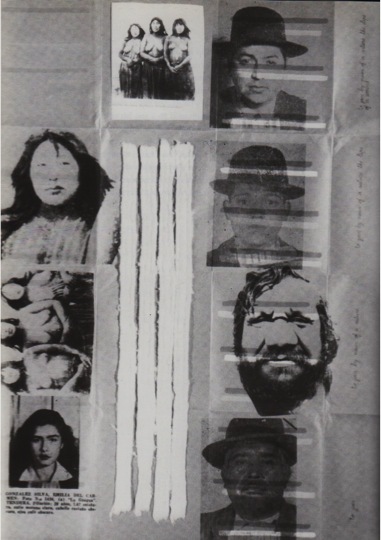

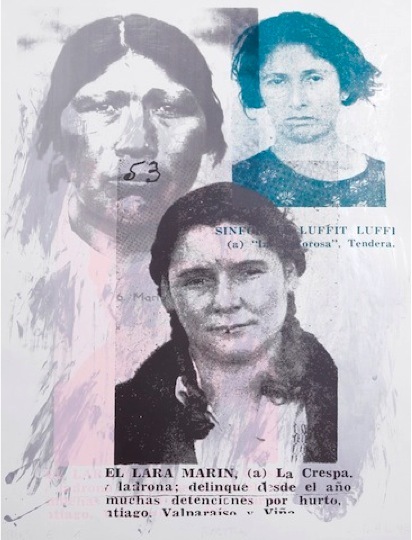

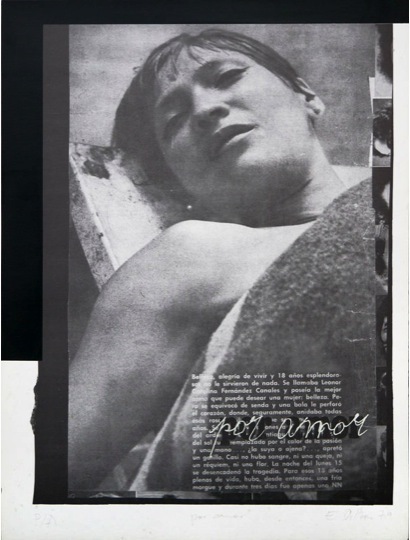

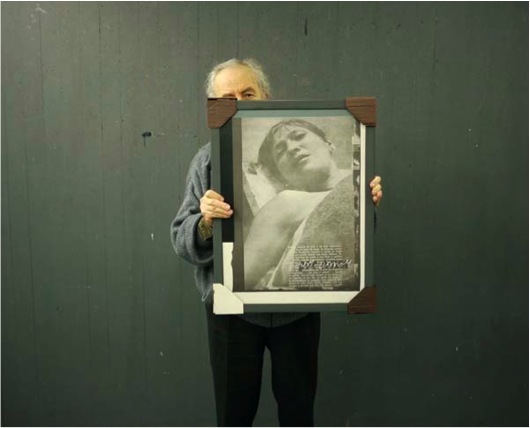

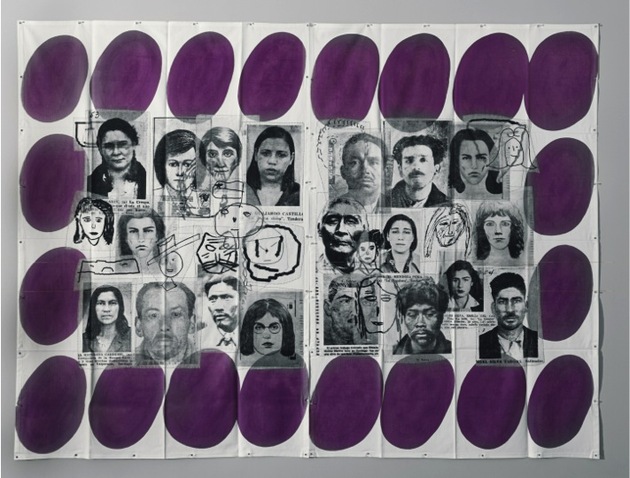

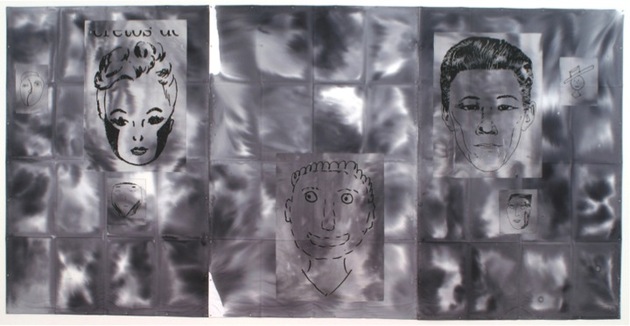

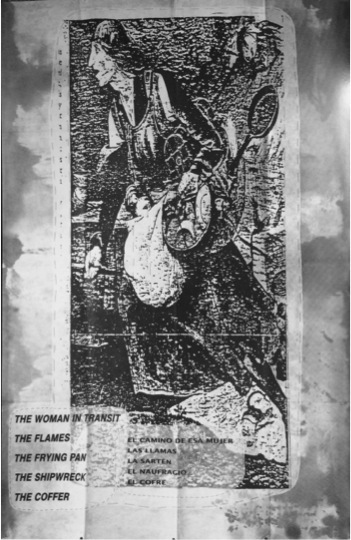

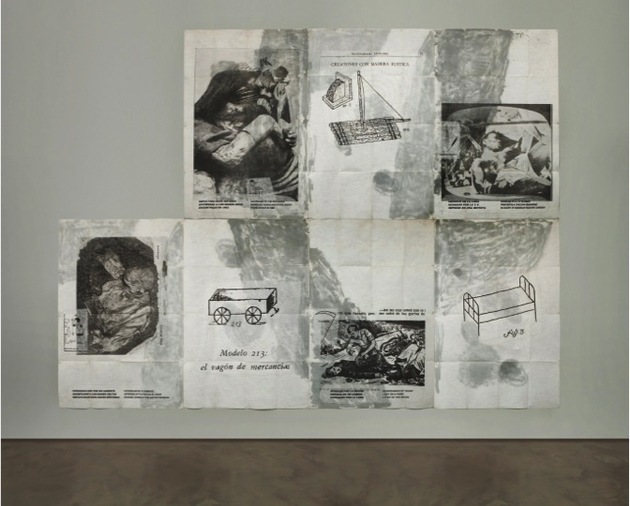

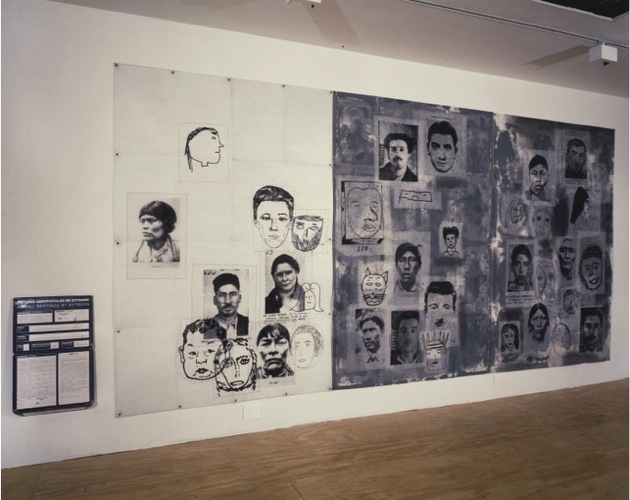

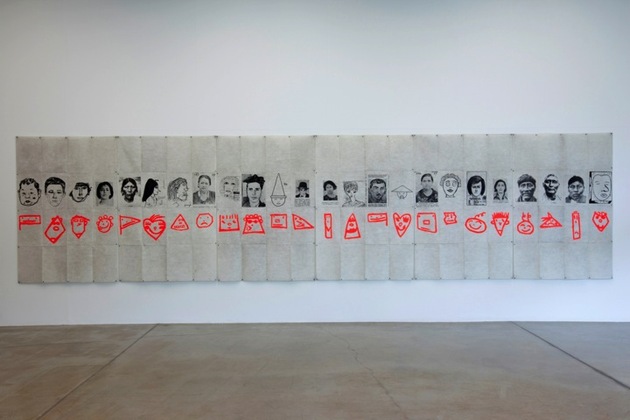

The images in his paintings are either “found” or commissioned, and he uses each one repeatedly. They were chosen, he has written, because they “amazed, disturbed, frightened, and sometimes tickled me.” He goes over them time and time again, combining them differently in each work, as if they were icons in a long chain of meditations, or unresolved issues. Here are a few of these images:

First, a Little Biography and a Little History

Eugenio Dittborn was thirty in 1973, a year marked by the military coup that would keep Chile under a dictatorship for seventeen years, until 1990. I met Dittborn around 1975. In 1978 I wrote about him for a Jesuit magazine, Mensaje, which was under the protection of the Catholic church, and thus was the only one to have a bit more leeway than others under the authoritarian regime. The piece referred to works by Dittborn in his valiant exhibition Final de pista (1977-1978). The works addressed subjects that were not welcome in the Chilean press of the day: mourning; grief; death and loss; forgotten, repressed faces such as you find in the images below. Its practices were not recognized as art in official circles. (Not that the military regime cared much about art, but they did put artist Guillermo Núñez in prison in 1974 or 1975, and tortured him, after an exhibition that included birdcages and was thought to refer to lost freedoms).

Times were obviously very difficult. I should remind you that more than three thousand people were killed after being arrested, that there were scores of “disappearances” and that thousands were tortured, that there was no freedom of the press, and that most people were afraid of losing their jobs for political motives—a rumor was enough. That was the fate of those who remained in Chile. Thousands of others were exiled; many left after seeking shelter in foreign embassies, and many were either stripped of their citizenship or not allowed to return for years and years due to having a letter L stamped on their passport. When they did return, there was—for a time—a gulf between them and those who had remained in the country, each side believing that their lot had been harder than that of the other. In either case, being “inside” or “outside” of Chile was a big issue in those years. This is something to keep in mind when considering the Airmail Paintings and, in particular, their format: the Airmail Paintings were able to “escape” and travel abroad, while Dittborn stayed inside the country for the most part.

Inside Chile, with many artists and most of the critics and writers in exile, people regrouped with difficulty and distrust. Today, when artists of the younger generation look back on those years, they identify names of artists, writers, and critics as well as many mimeographed catalogues, precarious documents, several gathering places (including Galería Época, Galería Cromo, Galería Sur, Taller de Artes Visuales, and Galería CAL) and many artists’ groups (including Escena de Avanzada,4This group consisted of Carlos Leppe, Carlos Altamirano, and Nelly Richard, basically, and it was in constantly changing constellations with other groups that included artists Eugenio Dittborn, Catalina Parra, Francisco Smythe, Roser Bru, and the CADA group, as well as with writers Enrique Lihn, Ronald Kay, Cristián Huneeus, me, and later, Justo Pastor Mellado. Grupo CADA,5Raúl Zurita, Diamela Eltit, Lotty Rosenfeld, Juan Castillo, and Fernando Balcells. and others, among them Eduardo Vilches and his school, which empowered many younger artists. )6See María José Delpiano, “Las operaciones críticas para el grabado en Chile” in María José Delpiano, Fernanda Carvajal, Carla Macchiavello, Ensayos sobre artes visuales: prácticas y discursos de los años ’70 y ’80 en Chile, (Santiago: Lom, CEDOC, CCPLM, 2011), 51–84. What is impossible to see from today’s perspective, however, is the fragmentation and precariousness, the peril, of those efforts. I personally remember the publication of critic Nelly Richard’s Margins and Institutions in 1986 as a sort of proof of our existence, and the amazement over what had been done, and exhibited, and written about under such conditions.7This book was published in Melbourne, Australia, with the cooperation of the Chilean painter Juan Dávila, who lived and worked there. Metales Pesados published it in Chile in 2007. Nelly Richard also came up with a catchy name for the scene, “Escena de Avanzada”; she included many people in it, creating a group identity that persists in many lazy classifications despite the protestations of many, among them, prominently, Dittborn, who has always refused to identify himself with that group (or indeed, with any other group then or since).8This is true even in Memoria chilena, the official site of Chile’s National Library.

In the late seventies and early eighties, the time when the first Airmail Paintings were produced, the perspective of the Escena de Avanzada held great sway in the unofficial art world, the “small and ridiculous battlefield,” which Dittborn remembers to this day. Controversies were many, heated, spiteful, and, to my mind, unproductive. Even though the “scene” hardly existed for either the media or the academic circles in universities dominated by the military, it created meaningful discussion and so being excluded from it could be rather painful, as Alfredo Jaar has repeatedly pointed out. Besides Jaar, it excluded artists such as Juan Pablo Langlois and Cecilia Vicuña, on grounds that their works were “sporadic” and “lacked a genealogy”9See Carla Macchiavello, “Vanguardia de exportación: la originalidad de la ‘Escena de Avanzada’ y otros mitos chilenos” in Delpiano, Carvajal, Macchiavello, Ensayos sobre artes visuales, 97. —that is, a connection to the Avanzada’s narrative, into which they did not fit. In all three cases, the future proved this assessment to be very, very wrong.

I would like to share with you two personal anecdotes about this. In 1981, after I wrote about him, I urged the young Alfredo Jaar to leave Chile. I told him that he had the potential to be a really great artist, and that he would suffocate in the Chilean art world, where he would have to spend his time and energy on rather worthless discussions. I had seen this happen to other people I also considered to be great artists. This zoo, I said, is much too small for such large animals. “Esta mujer,” he laughed, pointing at me during one of our conversations in 2005, “esta mujer me hizo irme.”10This translates, “This woman, this woman made me leave.” Alfredo Jaar, JAAR SCL 2006 (Barcelona: Actar, 2006), 73.

The second anecdote is about Gonzalo Díaz, who, like Eugenio Dittborn, has been awarded the National Prize for Fine Arts. In the early eighties Díaz asked me to write about him. To protect myself in an unfriendly art world, I asked him to show me first what else had been written about him. “There is only one text,” he said. “It was written in 1979. But to tell you the truth, I no longer understand it, and I don’t think the author does either.” This small battlefield was full of personal allusions, private jokes, hidden quotations, as well as poorly digested art theory and willful omission of sources. So no wonder. Hopefully these anecdotes will give you a sense of the stifling times in which these first Airmail Paintings were created—and account, at least in part, for the impulse to flee and to get the work out of such a context of reception, even if the artist himself did not settle elsewhere.

Nowadays, the Chilean perspective on the “Escena de Avanzada” and the success of its label, particularly in American academic circles, is very different. Recent discussions have described it ironically as a “heroic myth” that has weighed heavily on younger artists, hindering their development.11See Pablo Chiuminatto, among others, in https://artishockrevista.com/2014/09/04/conceptual-stumblings-reporte/ It has been pointed out that its narrative is decidedly incomplete, and that historic research into its archives would undoubtedly paint a very different picture. The field is open and, frankly, it is most refreshing to see how new and informed researchers look askance at the narrative that once petrified the small Chilean art world.12CEDOC, particularly.

A final note on the small battlefield: In the late eighties and nineties, Dittborn became “totemic,” to use [the critic] Justo Pastor Mellado’s catchy term. Mellado’s narrative referred to him and to Gonzalo Díaz, an influential artist and professor at the University of Chile, as “padres totémicos.”13This translates “totemic fathers.” They were cast as Saturn, the god who eats his own children14Among many references, see Justo Pastor Mellado in Gerardo Mosquera, Copying Eden, Recent Art in Chile (Santiago: Puro Chile, 2006). and the younger artists were cast as the rebels who needed to overthrow and indeed to kill their all-too-powerful influence. Dittborn’s concept of a “bunker” comes to mind, for this kind of talk was still influential as late as 2006.

Yet things have changed for Dittborn in the more recent Chilean democratic context. He enjoys recognition. He was awarded the highly coveted National Prize for Fine Arts in 2005. Even better, there is a whole new generation of artists and writers on art who know and admire his work, write about it constantly, and understand its motivations and inner contradictions in a way that is far beyond the “masterly,” paternal, and Saturnal slurs of the nineties. Besides the valuable critical consideration of Nelly Richard, Ronald Kay, Enrique Lihn, and others (I among them) in Chile during the seventies and eighties, there is now a body of recent work by Ana María Risco, Bruno Cuneo, Fernando Pérez Villalón, and others, which must be taken into account from now on. It will help us in terms of thinking about the Airmail Paintings right here in this talk, and in going beyond what I have termed rather sloppy catchwords. Furthermore, Dittborn is very much back in the graces of the even younger artists in his native country, not as a threat but as an inspiration. But enough of the rather stifling atmosphere, enough of Chilean tensions. Let us move on to the work, which will say a lot more than these generalizations and lead us to ever wider and deeper, multilayered spaces.

Dittborn’s Breakthrough: the Airmail Paintings

Wider spaces were precisely what Dittborn had in mind, and desperately needed, in the early eighties. In those years, facing the dilemma of leaving Chile or staying, he actually created a third option—his Airmail Paintings. He began circulating the first ones in 1983. There are now more than 180 of them, and they have traveled all over the world.

Many of the images contained in the Airmail Paintings appear in Dittborn’s work from before; they are the images that obsessed him from at least 1977 on. His 1977 exhibition Final de pista, was, he said, “based on the prolonged observation of photos of human bodies” in extreme situations of exertion, or even in death, as in the work La Pietà. Dittborn’s Pietà is based on an image captured by camera from a TV screen, in which a dying boxing champion is held by his second. An image that had “amazed, disturbed, or frightened” him, it has reappeared in many of his works, as if he were repeatedly processing it.

In 1977-1978, in Chile, Final de pista was an exhibition that included many works using found images connected with death, physical torment, media alienation, anonymity, erasure. It was in “rigorously monochromatic chiaroscuro” (Dittborn). I think of Final de pista both as an end and as a beginning. It is the pictorial beginning of a very long and complicated period of mourning that is apparent in his work. And it is the end of the way his work had circulated up to that moment. From that point on, it would circulate in envelopes, and be carried around the world by postal services.

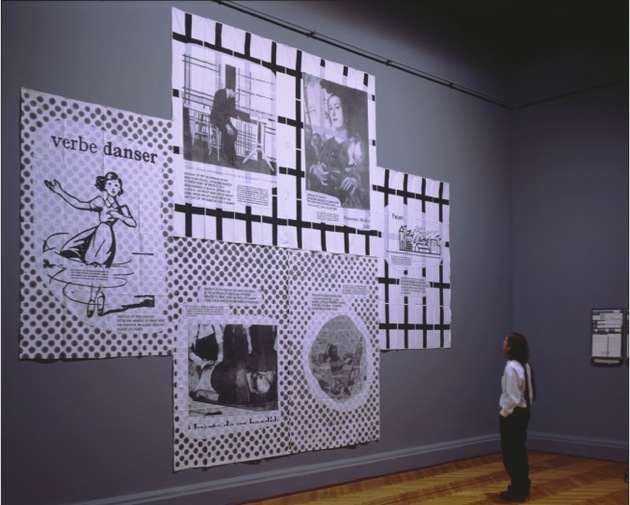

Dittborn has said that he stumbled upon his Airmail Paintings, a “pragmatic invention,” as Guy Brett has called it, and that it all started with an accidental discovery while exploring the possible pictorial uses of large sheets of brown Kraft paper. He discovered that a large sheet of paper could fit into an envelope when symmetrically folded, and thus become a small, mailable package. He also found that, upon reaching its destination, such a package could be opened and its contents displayed, occupying considerable exhibition space. The artist was also impressed by the possibilities of the folding process, which creates creases that divide the surface into sixteen compartments. These creases are always carefully preserved when the paintings are shown.

Before coming upon this format, Dittborn exhibited similar images in a large, heavy, non-portable format:

For creating larger Airmail Paintings, he went on to use more than one sheet, creating, say, polyptychs of five or more sections, each sent in a separate envelope; when hung together, they are enormous in scale and yet they weigh practically nothing.

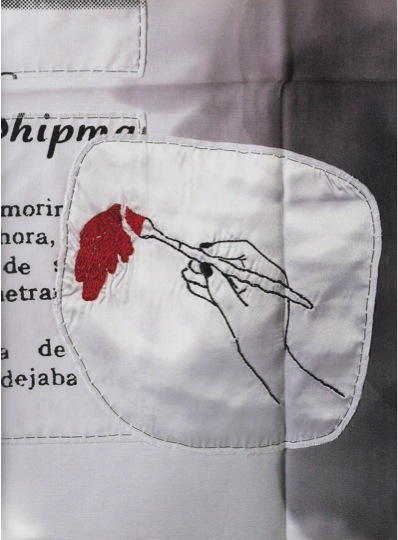

Dittborn replaced the brown paper in around 1989 with white nonwoven fabric, which adds dimension. This fabric, used in tailoring for lapels and shoulder pads, not only retains the folds, it also is able to absorb liquids, to be stained, and to bear stitching and even buttons. Each new material brought with it new possibilities. In 1995 duck fabric became the surface of choice.

In 1999 “grafts” started appearing: pieces of cloth, usually sateen, sometimes cotton or polygal with embroidery and, above all, tincture. Tincture was the last stage of the comeback of color. If we remember that the paintings started as “rigorously monochromatic,” and that the first color to be introduced after black and white was violet-purple, we see a journey that reminds us of the sequence of traditional mourning clothes: first black; then black and white; then violet-purple. Then the other colors appeared on the surfaces as if spilled on them. During the later periods, spilled tincture took over the whole surface, and small images seem to be precariously superposed to it.

The envelopes themselves—in gray and white in their final version—were designed by the artist, and they are a visible record of all the places in which their contents, the paintings, have been displayed. They bear each one of the addresses, as well as postage stamps and other utilitarian markings. Sometimes they also display carefully calligraphed texts. They are exhibited alongside the paintings and are considered part of the work.

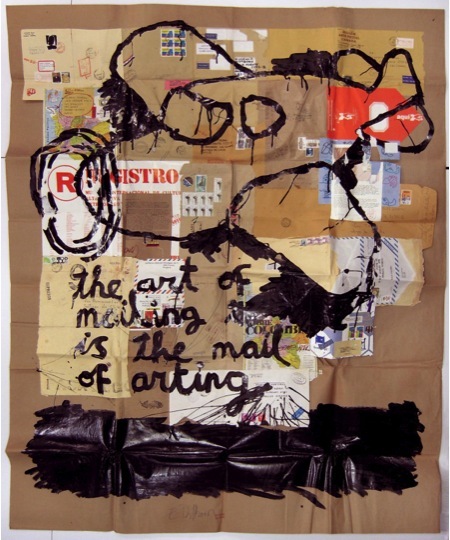

Some of you may be wondering about the relationship between this work and mail art. This invention by Dittborn has a certain genealogy and background to it, as do most inventions. A 2012 Airmail Painting titled Ronsard meets Ray Johnson and sent to the Correspondences exhibition about Mail Art in France seems to allude to an impossible meeting in imaginary time and space between two great cultural figures—a sort of collision taking place in a nowhere land between Ronsard, the French poet so often present in Dittborn’s work when he is lamenting the fleeting nature of human passions and human bodies, and the creator of the New York Correspondence School, whose death at an early age impressed Dittborn. Mail Art had been in the air for decades when Dittborn invented his Airmail Paintings, and some of its momentum and ideas probably helped ignite the spark in his own mind.

MoMA has recently acquired from Franklin Furnace an early Airmail Painting, probably one of the first, which is quite interesting. Signed by Dittborn in 1982, I think, it is different from his other early works. It seems to be something of an experiment, and it is decidedly comic in character, because of its use of sticky black tape and childlike writing in bad English. (“Bad English is the language of the future,” the American novelist John Irving once wrote.) Envelopes are present here, but instead of containing the painting, they are pasted onto its surface and shown, addresses and all. One of them is from Guillermo Deisler, a Chilean artist exiled in Germany, who was important both for mail art and for visual poetry. So that, too, could be part of the spark that would set the house on fire for Eugenio Dittborn, and produce a major breakthrough in his artistic practice. In fact, this work may provide an excellent introduction to the Latin American political operations of Airmail Painting. “America is not a set of icons. America is a set of ways of dealing with the icons, whatever their own origin.”15Adriana Valdés, “Eugenio Dittborn, Airmail Painting No. 95 (dyptich), 13th History of the Human Face (Dulle Griet, Paraca y el Torche)” in America, Bride of the Sun, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, 1992.

Dittborn’s breakthrough, his eureka moment, allowed him to create what Guy Brett has considered a new genre: the Airmail Paintings, with conventions that defy easel painting, mural painting, etc. What makes them different is that they are fashioned for and by travel. They are not made to remain in one place. They enable the painter to be effectively an escape artist; to go beyond the narrow context of reception that seemed reserved for him in his own country; and to open whole new spaces of action, possibilities, and dangers in different contexts of reception all over the world.

This is why travel, as a concept and a context, is basic to what we are addressing today, even from a political point of view. Dittborn is not trying to be difficult when he answers a question by saying that his politics are in the folds of his Airmail Paintings; he is being Latin American. It is all about access, and free movement, and presence in prestigious spaces—or the lack of them. He will also say that the lines of his drawings are those created by the movement of his envelopes across the map of the world. It is the way to make Latin America a place of origin, as well as a destination.

Travel is a political necessity for Dittborn’s work. Crossing the oceans, both figuratively and in fact, is a political must. His paintings have been described variously as “messages in a bottle,” such as those sent by people abandoned at sea; or as Trojan horses; or even, remembering the film The Man That Never Was, as corpses carrying false messages in order to mislead an enemy.16Ana María Risco, “Disarmed and Equipped: Strategies, Politics and Poetics in Eugenio Dittborn’s Airmail Paintings,”Afterall (Spring 2012). https://www.afterall.org/articles/disarmed-and-equipped-strategies-politics-and-poetics-of-the-image-in-eugenio-dittborns-airmail-paintings/ The last two metaphors come from war, and point to a battlefield different from “the rather small and ridiculous” one Dittborn found in Chile. Yet it is a battlefield nonetheless, and guerrilla tactics are also mentioned more than once when speaking of the Airmail Paintings.

I would bore you (and myself) to tears by simply mentioning center and periphery. This binary opposition is, of course, much too simple and dated. And I would argue that what is most interesting about Dittborn’s work and its world travels are precisely all the layers and nuances and crossings and tensions that he is able to make us see, if we are willing to lay aside certain lazy clichés that keep us from exercising our own powers of observation.

Travel is fraught with dangers, among them some of the “master narratives” of globalization, political correctness, and the expectations artists suppose they are required to meet, the mental models in which they think others expect them to fit. Dittborn’s work actively resists being read as a cliché. It actively resists being classified too easily, or integrated into categories created by others. It is not made for sweeping glances or sweeping statements. Indeed, its politics are, like he has said, in its folds; they are in the creases, which are carefully preserved for exhibition. They signify the journey, along with the envelopes that are also exhibited and bear the traces of the other journeys made by the same work. Their modus operandi is an important part of their message, or indeed the message itself.17Ibid. The main message of every Airmail Painting is one of strangeness and of distance. It insists on being an alien message: the Airmail Paintings come from another world and make this apparent. There are certain logistics of infiltration . . .

The surface of an Airmail Painting juxtaposes images that are totally discontinuous, both in time and in cultural space. The eye and the mind wander, go every which way, are disoriented. There is no horizon line to guide either the eye or the mind. And “guessing the sources of the images, particularly in works (. . .) such as The History of the Face series, can be part of the fun in viewing a Dittborn,” wrote Sarah Thornton. It is a take I like, because Dittborn can be fun, but I believe there is another angle to viewing a Dittborn. In the words of Bruno Cuneo, in an Airmail Painting, “There is no one statement (. . .) but rather a field in which tensions and connections appear between signs disjointed or bereft of any unifying idea—but not of a grammar or a poetics where connective chasms and maximum compression are important.”18Bruno Cuneo, “Deadline,” in Eugenio Dittborn, Nocturna (Santiago: D21 Editores, 2014). I like these “connective chasms,” this “maximum compression.” They remind me of the expression “farfetched,” which is used in explaining baroque metaphors. The thing is that connections are possible, but difficult. The connections are, in and of themselves, discoveries, and the Airmail Paintings require a lot of looking in order to make those discoveries—and to exult in the idea of maximum diversity and maximum unexpected contact. And so these works don’t “have” a meaning; rather, they “run on meaning, like a car runs on gas.19Sergio Rojas, “La dieta de los artefactos”, in _Lecciones de cosas, 7 textos +postfacio sobre Quadrivium de Gonzalo Díaz_ (Santiago: Editorial La Blanca Montaña, 1999), 38. “Quadrivium se alimenta de sentido, este es, para ser más precisos, su combustible.” They are a sort of playground for many layers of meaning, some of them quite loaded. Like guns.

Take The History of the Face series, for example. (The last image I have is The History of the Face Number 30, but there may be other later ones.)

Let me mention the total strangeness of photography and its distance in relation to the New World, where most indigenous subjects and objects were, in Ronald Kay’s word, “prephotographic,” anachronistic, assaulted, and surprised by a camera that did not belong in their own era.20Ronald Kay, Del espacio de acá, Señales para una mirada americana (Santiago, Editores Asociados, 1980), 26ff. They were thus condemned to be seen as “exotic,” and to live in two historical times: their own and that of a “modernity” utterly foreign to them. They were condemned to be “captured.” Even if they posed willingly—and many didn’t—they were, in fact, captured, stereotyped, and used by photography in ways they could not imagine. Many of the images you will see in Dittborn’s work—that of Jemmy Button; those of the Selk’nam people from the southernmost tip of South America, now practically extinct; and also those of petty thieves captured by police ID cameras in the thirties in Chile, have this poignancy to them.

Add to this the feeling of total strangeness, of alienation, in an “identity”: the human face seen by the camera, but also juxtaposed with the human face seen in a “retrato hablado,”21This translates “Identikit.” or in the drawings of children, or in how-to-draw books, or in drawings commissioned from the inmates of an insane asylum. These are memories, but not personal memories; archives, but not personal archives; traces, relics, but those of others, both local and global.

I don’t want to go on too long. Yet I’d like to ask—rhethorically—how big words such as “culture,” “identity,” and “Latin America” look like after seeing several Airmail Paintings. We could speak of discontinuity, of grafts, of relics, of faint traces on intractable surfaces, of the insufficiency of our own mental frameworks, on how to infiltrate a globalized world; we could speak of the impossibility of assuming single origins, or even origins at all; we could speak of so many things. I’d like to finish, though, by putting all of this firmly back into the Chilean context from which all these moves were made, and for that I will use eight lines from a younger friend and disciple who has clearly outstripped me:

“The ghostly, moving and ungraspable condition of historical fragments that meet and crash on the airmailed surfaces (. . .) leads us to consider them (. . .) as attacks from a memory both private and shared, local (Chilean, Latin American) and global. It is the memory of a historical subject placed in shock—as Chile was in 1973—beginning to connect itself with its past in the aftermath of a profound trauma (. . .) Full of grafts and patches, of juxtaposed images or bits of cloth sewn over the main fabric (. . .) the body of an airmail painting is seemingly nothing but a displacement and forgetting of origin. . .”22Risco, ““Disarmed and Equipped,” p. 75.

Note from the author: My deep gratitude to Eugenio Dittborn, to Felipe Cooper and Maria Gabler, and to Carolyn Alexander, Alexander&Bonin, Dittborn’s gallery in New York, for most of the images.

- 1See https://www.economist.com/news/2011/01/19/el-genio-dittborn. A longer version of this article appeared in Sarah Thornton, Thirty-three Artists in Three Acts (London: Norton & Norton, 2014).

- 2In Spanish the artist’s first name, Eugenio, sounds extremely similar to the phrase “un genio,” which translates “a genius.”

- 3Dittborn has been producing his Airmail Paintings for more than three decades. Each of them is folded and placed in a specially prepared envelope, and each of them travels the world on its own, particular itinerary. For more information, see Dittborn, Eugenio, Mundana: 24 pinturas aeropostales en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Santiago de Chile Santiago (Chile: Pública Editores, 1998).

- 4This group consisted of Carlos Leppe, Carlos Altamirano, and Nelly Richard, basically, and it was in constantly changing constellations with other groups that included artists Eugenio Dittborn, Catalina Parra, Francisco Smythe, Roser Bru, and the CADA group, as well as with writers Enrique Lihn, Ronald Kay, Cristián Huneeus, me, and later, Justo Pastor Mellado.

- 5Raúl Zurita, Diamela Eltit, Lotty Rosenfeld, Juan Castillo, and Fernando Balcells.

- 6See María José Delpiano, “Las operaciones críticas para el grabado en Chile” in María José Delpiano, Fernanda Carvajal, Carla Macchiavello, Ensayos sobre artes visuales: prácticas y discursos de los años ’70 y ’80 en Chile, (Santiago: Lom, CEDOC, CCPLM, 2011), 51–84.

- 7This book was published in Melbourne, Australia, with the cooperation of the Chilean painter Juan Dávila, who lived and worked there. Metales Pesados published it in Chile in 2007.

- 8This is true even in Memoria chilena, the official site of Chile’s National Library.

- 9See Carla Macchiavello, “Vanguardia de exportación: la originalidad de la ‘Escena de Avanzada’ y otros mitos chilenos” in Delpiano, Carvajal, Macchiavello, Ensayos sobre artes visuales, 97.

- 10This translates, “This woman, this woman made me leave.” Alfredo Jaar, JAAR SCL 2006 (Barcelona: Actar, 2006), 73.

- 11See Pablo Chiuminatto, among others, in https://artishockrevista.com/2014/09/04/conceptual-stumblings-reporte/

- 12CEDOC, particularly.

- 13This translates “totemic fathers.”

- 14Among many references, see Justo Pastor Mellado in Gerardo Mosquera, Copying Eden, Recent Art in Chile (Santiago: Puro Chile, 2006).

- 15Adriana Valdés, “Eugenio Dittborn, Airmail Painting No. 95 (dyptich), 13th History of the Human Face (Dulle Griet, Paraca y el Torche)” in America, Bride of the Sun, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, 1992.

- 16Ana María Risco, “Disarmed and Equipped: Strategies, Politics and Poetics in Eugenio Dittborn’s Airmail Paintings,”Afterall (Spring 2012). https://www.afterall.org/articles/disarmed-and-equipped-strategies-politics-and-poetics-of-the-image-in-eugenio-dittborns-airmail-paintings/

- 17Ibid.

- 18Bruno Cuneo, “Deadline,” in Eugenio Dittborn, Nocturna (Santiago: D21 Editores, 2014).

- 19Sergio Rojas, “La dieta de los artefactos”, in _Lecciones de cosas, 7 textos +postfacio sobre Quadrivium de Gonzalo Díaz_ (Santiago: Editorial La Blanca Montaña, 1999), 38. “Quadrivium se alimenta de sentido, este es, para ser más precisos, su combustible.”

- 20Ronald Kay, Del espacio de acá, Señales para una mirada americana (Santiago, Editores Asociados, 1980), 26ff.

- 21This translates “Identikit.”

- 22Risco, ““Disarmed and Equipped,” p. 75.