These documents were originally published in print in Listen, Here, Now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, part of MoMA’s ongoing book series Primary Documents series. This selection is newly compiled by the book’s editor Inés Katzenstein, Director of the Department of Art at the Universidad Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires.

Sections of the publication were also edited by Andrea Giunta, Ana Longoni, and Mario Mestman.

Source contents

Vivo-Dito Manifesto

By Alberto Greco, 1963

Publication: Version from the artist’s writings

Language: Spanish, translated by Maguerite Feitlowitz

Vivo-Dito art is the adventure of the real, the urgent document, the direct and total contact with things, places, people, creating situations, creating the unexpected. It means showing and encountering the object in its own place. Totally in accord with cinema, reportage, and literature as a living document. Reality without touchups or artistic transformation. Today I am more interested in anyone at all recounting his life on the street or in a streetcar than in any polished, technical account by a writer. That is why I believe in painting without painters and in literature without writers. This explains why, in recent years, the visual arts have consciously found recourse in chance. It was a way of discovering the other side of reason. All our conscious thought, all our reason limits us, and we fall, very easily, into elementary and limited structures. “Always go in the direction opposite to the one you should. It’s the only way to get somewhere.” I find that stupendous.

I don’t know if I said this before, but we must go out into the street and not see it as a means of transport, as though everything were a commercial object, or a streetcar that takes us from one place to another. Every death or, better said, every corpse—directly or indirectly, of course—has its assassin. Although this is not the time to cast blame on anyone as it would be too puerile, too simple, I believe dealers have greatly contributed to the demise of painting by turning it into a domestic and commercial object. The prints traced by my shoes on the way from my house to the gallery are more important than the canvases on view there. I don’t know who said that, but I totally agree.

A work has meaning as long as it is made as a total adventure, without knowing what is going to happen. Once it’s finished, it doesn’t matter anymore, it has become a corpse. So let it rest in peace. The contemporary artist has lost his sense of eternity. The passivity of the public should also come to an end. The audience, as audience, should end. Everyone knows too much, or at least seems to, about his own life. And what more can we ask of a person if not to tell something to make his listener shudder? Let us hope that the activities of Vivo-Dito will turn things inside out so that the audience will do the talking. We must not forget that Vivo-Dito is above all the adventure of the real and of the direct contact with things. Art galleries are opaque whorehouses that have fallen into decadence next to the butcher shops, bakeries, markets, tailor shops, theaters, subways, morgues, streets, and real whorehouses.

Conversation in an elevator, looking at the stains on the wood.

—Which is better? This, or doing this?

—This.

—Bring him to see or bring them to see?

—Bring them to see.

Grand Vivo-Dito Anti-Manifesto Manifesto Scroll (excerpts)

By Alberto Greco, 1963

Publication: Excerpts reproduced in Alberto Greco (Valencia: IVAM Centro Julio González, 1991)

Language: Spanish, translated by Maguerite Feitlowitz

Buy the “Grand Vivo-Dito Discourse Anti-Manifesto Manifesto” with: (colon). Greco clarifies and explains his performance in Cristo 63.1A scandalous theater piece that Greco performed in Rome in 1963, for which he was obliged by the police to leave Italy. Tombalos, tangos, crime, cartoons, income, letters between relatives. A confession bought right now and forever.

( . . . )

I know that with so much tango the rhythm gets lost, but so what? Let the tango play on.

( . . . )

Steal ideas of mine? Steal my VIVO-DITO? Ha, ha! If anyone dares, I’ll sign.

( . . . )

I want to make total theater, improvisation, with the audience creating situations, therefore with no audience. Total adventure, for example, the total adventure of a spectacle, the total process, until it takes form. When it’s “done,” be done with it, for example, as if it were no more than a common theatrical show. One should attend every day. But I know that it would be over on opening night. Everything opposite to the way it’s always been done, with that absurd sense of perfection and finish.

( . . . )

As usual, when you least expect it, the parachutist falls. I received an invitation from Nice where they are going to do what one has been doing for years. They steal everything, everything, and one is always played for an ass, there is always a Pucciarelli2Mario Pucciarelli, born 1928, Buenos Aires, an Informalist painter who was awarded the Di Tella National Prize in 1960. hiding in some corner. I will write to Bertholo to see if his sense of justice will allow him to deign to dedicate a few pages to Arte Vivo-Dito and to the Grequistas vivant in view of this latest and all the earlier ones besides. Let us hope this happens. One struggles as always and spills blood for one’s stubborn faith.

( . . . )

1954: I signed walls, objects, streets, and bathrooms in Paris, accompanied by Peñalva Lerchundi.

1961: I signed the city of Buenos Aires.

1962: February, I exhibited my live rats. Sala BACSAC, Galería Krausel.

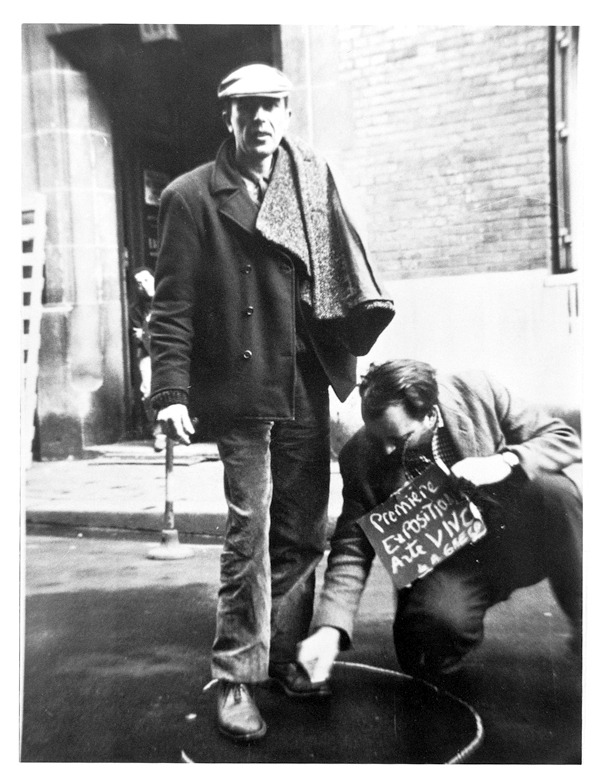

1962: Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris. I exhibited and consecrated myself as a work of art. June 1962. Manifesto Dito of Arte Vivo published in Genoa, Italy.

L.A.[^3] is the adventure of the real. The artist will no longer show with the painting, but with the finger. L.A. is direct contact, it must happen right in the street, with people, multitudes, rumors, situations.

1962: August. Paris. Arte Vivo-Dito demonstration directed at K.W.Y. Consisted of signing old ladies and antique shops.

1962: I signed 32 heads of lambs with their throats cut in the trusty Paris market. I signed the market with a finger in the air, accompanied by a painter and another theater director from Montevideo (both women and both very well-known). Of course they laughed. They never understood the man in action as a true work of art.

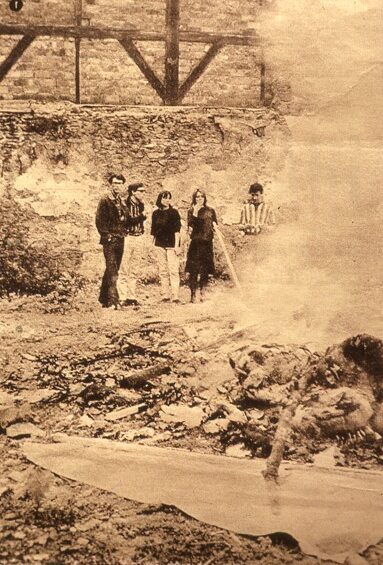

1963: Incorporation of objets vivants (people) into the canvases. Text on the back of the photo: Greco positioning a lady to create the living space in the picture, in the canvas. I, Greco, Grequísimo. I sign Ben as Arte Vivo-Dito’ s Continuator No. 6 in the world.

Against the Happening

By Roberto Jacoby, 1967

Publication: Originally published as “Contra el Happening,” in Oscar Masotta et al., Happenings (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1967)

Language: Spanish, translated by Eileen Brockbank

Within the field of the creation of works of art inside the mass communications media, the one we executed was just one possibility. To carry it out, we needed to obtain the support of the supposed participants and of the journalists. We explained our objectives to each, adapting our explanation to what each wanted to hear. If someone thought that it was all just a big joke, we convinced him that in fact it was just that (a public relations technique). These ad hoc explanations became confused with our true intentions when we created the piece; later they contributed to complicating its intelligibility.

One of those explanations consisted in reducing the work’s intention of demonstrating that the press deceives and deforms. This phenomenon, which is obvious and a matter of common sense, is actually only tangentially addressed. The fundamental content of our work is slightly more complicated: a play between the reality of things and the unreality of information, between the reality of information and the unreality of things; the materialization, through the mass media, of imaginary events, an imaginarium constructed on another imaginarium; the game of constructing a mythical image and the job of seeking the support of the audience’s imagination, only to tear it all down and leave them simply with “the spectacle of their own deceived conscience.”

One could also say that here thousands of spectators literally construct the work, but not as usually happens, springing from a concrete stimulus; rather it arises from an account of the piece. The account of something that did not take place (and therefore false, fictitious) was not however a simple literary fiction—as it would have been had it been included in a collection of stories—but the communicational context endowed it with a factual rather than a literary materiality. Another idea, that of playing a joke on the audience, excited some people who think that avant-garde art should be, above all, fun. That in itself should not be dismissed out of hand, but this piece does not contain the slightest trace of a sense of humor. As for the explanation that it is a sociological experiment, that is not altogether the case, since it is obvious that it does not meet the requirements for a true sociological experiment. But as Harold Rosenberg wrote us: “It is a sociological work, and that does not make it less valuable.” But just the same, it lacks rigor as a sociological experiment, so it is sociological as a work of art. Its very “materiality,” the mass communications media (concrete and material magazines and dailies), is more social than physical.

To put our idea into practice, we resorted to certain techniques used in “public relations” and not to “artistic” techniques. We had to interview people who are news- worthy, be polite to them, earn the support of journalists: in short, move inside these groups with the strategy of robbing the group of its dynamic, freezing it. We were trying to offer each the image of the overall situation that each imagined in his or her own mind. According to that strategy, it was appropriate that the topic we would be informing about be a myth: the Happening myth. In order to refer to that myth, we proceeded inversely to the way plastic artists work nowadays, by extracting a segment of the context to evaluate it aesthetically. We, on the other hand, homogenized a series of real events that had been mythicized through language (that of the news in the media) into an event that only existed through language. Thus, language became a factor of homogenization as much as of mythification. “Really the best defense against a myth is to mythicize it in turn, that is to say, produce an artificial myth: and that myth reconstituted will give way to a true mythology. Since myth robs language, why not rob the myth? This would be sufficient to convert it into a starting point for a third semiological chain . . . a second degree myth.”3Roland Barthes, Mythologies. But the myth of the Happening was not in itself the work’s “message.” What was communicated was the paradox between the characteristics of the Happening (the lack of mediation, direct communication with objects and persons, short distance between the viewer and the viewed) and a great deal of mediation between objects and events, the nonparticipation of the receptor; in short, the conditions imposed by the mass media as a means of communication. In this way the message consisted of two levels: one aesthetic, the other mass-oriented, therefore implying a certain interpretation of one by the other. The “aesthetic” level was mediated by the “mass” level, that which concretely reached the receptors. In this way, what at first glance might look like a Happening became an anti-Happening because of the relationships it created with objects. “The point is to think then of an art of objects that we are not yet prepared to imagine, the material of which must not be physical but social and whose form should be constructed through systematic transformations of communications structures. Objects, in short, that will be difficult to preserve in museums for future generations.”4Eliseo Verón, article reproduced in this book. [Not included in the present anthology. Ed.]

When someone decides to paint a picture—whatever the style, the subject chosen, the skill of execution—he decides, by the very decision to “paint,” on a message. A “medium” (oil and canvas) not only transmits significant messages, but the medium itself, as opposed to other mediums, is significant. What is more, the medium “sets the stage”; it induces minds and bodies to a certain precise perception of time and space. The decision to choose one medium and not another implies ideas about the material and social possibilities of establishing communication. But just the same, they are ideas about society. When, for instance, an artist chooses a planar medium rather than a sculptural or a theatrical one, there are totalizing conceptions that do not reside in the “content” of what is said, but rather in the medium chosen to say it. Mass communications media have been analyzed in this regard, but the same has not been done with aesthetic mediums. These have been constructed on true myths, and as happens with all myths, they have wound up being naturalized to the point that no one challenges their validity. While it is possible to argue about the advantages, defects, and characteristics of television, it would not occur to anyone to question painting, dance, or theater. There is an acritical conception of aesthetic mediums by which they are accepted just as they are presented to us. There are attempts at innovation in the fine arts by changing “contents” and “formats,” when the problem really is: one medium or another. The concept of medium includes the categories of content and form, but for that very reason the discussion must be lifted out of this last level and be elevated to media as such.

The existence of mass communications media on one hand and aesthetic media on the other gives rise to split between two parallel cultures, one of the masses and the other “superior,” of the elite. The awareness of this split between the values of mass culture and those of the elite has become heightened among artists and intellectuals during the last ten years. Pop seemed to want to erase the separation by reproducing images produced by the mass media. It is as if these artists had tried to burst the limits of their own medium to turn their works into messages that would be distributed and accepted on a mass scale. Lichtenstein and Warhol, by reproducing comic strips and labels, turned the products of mass communication into the content of an aesthetic medium. For a Pop artist it is possible to regard the products of mass culture as beautiful, but only with the mediation of the aesthetic medium. In contrast to this idea, I believe that mass communications media have a materiality that is susceptible to being aesthetically shaped. We have only to look as far as writing and film, which were initially commercial techniques and scientific oddities. Taken later to aesthetic ends they became the new aesthetic media and, up to a point, worked as substitutes for the earlier media. The new media today are those of mass communication. And as new media, they offer a new way of perceiving and behaving. Cinema (a medium that sometimes behaves like an aesthetic medium and sometimes like mass media and in some cases is able to overcome this dichotomy) required the creation of new teams of manpower and technical equipment. In the same way, mass communications media art demands that the artists, if we are to call them that, be situated inside it, discover its functions and techniques.

We know full well that mass communications media are essential to controlling a society and are therefore implemented—no less than was writing, in other times—by the groups in power today. “Their manipulation, then, entails many perils for the artist and for the correct comprehension of his activity on behalf of the public. I would even say that they are sufficiently complex systems as to make it difficult to escape their ideological traps, even when one believes himself to be condemning them.” This requires of future artists that on one hand they be very well acquainted with the material they are going to work with and, on the other hand, that they be affiliated with social groups powerful enough to make their cultural messages heard. This obliges us to think in an entirely different way about words like “artist” and “art,” and to rethink the whole creative process. Once again, as when the Gothic cathedrals were being built—the artist ceases to be an isolated individual. “Artists are abandoning the ivory tower,” says McLuhan,5Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966), p. 65. “for the control tower.”6But the one who controls is in turn controlled. The information media, in every kind of society that has existed to date, are controlled by concrete social groups that ideologically infiltrate the media. This presents a new and serious problem since the artist can no longer work in isolation from the groups that own and control the information media, be they dominant groups, sectors of the state, parties, companies, or unions. To some degree film had already obliged artists to take into account the different interests of different groups and in a way, film is always a kind of conciliation of those interests. No doubt mass information media art will accentuate the phenomenon. The artist will be unable to create outside of concrete social groups. Seen from an individualistic viewpoint, this position, which is nothing more than a description of the situation, may seem painful, or outright cynical and totalitarian. For this reason, in the modern aesthetic message, the expressive function focused on the transmitter, which has tended to diminish in all modern art, and the cognitive or referential (that points to the context) may subside, though without disappearing, before the conative function of the aesthetic message. It will not be about, most likely, expressing the artist’s emotions or “showing reality” but about acting on the receiver, about “making making.” The predominance of the conative function will move art closer to propaganda and to the study of the structures of persuasion, just as at the turn-of-the-century art moved closer to mathematics and industrial techniques. What is more, perhaps, the old conflict between art and politics (“Art should reflect reality”; “all art is political”; “none is”; etc.), which people have tried to transcend by introducing a political “content” into art, will be settled by the artistic use of a medium as political as mass communication. The “moments” of the art of mass communications media would then be:

a) the transmitter; set up inside of teams familiar with communicational techniques;

b) the message, the materialization of which will be more social than physical. Discontinuous works (televised messages, waves of graphic information, posters, billboards, projections, radio transmissions, demonstrations, etc.); the predominant function of the message will perhaps be conative, encouraging making. Disappearance of the boundaries between mass culture and the culture of the elite.

Reflecting on the origins of Happenings, it is easy to see how artists coming from different artistic fields converged to form a hybrid genre. Painters, dancers, musicians, filmmakers, theater people, etc., crossed the boundaries between traditional genres, looking for the outlet they could not find in their own medium. Since 1952, when John Cage gave his famous performance at Black Mountain College, to the present, it must be said that the somewhat dying history of Happenings is the history of a desperate search for a new means of aesthetic communication. Today we know that if there is any hope for contemporary art, it is not the Happening, since the Happening, instead of becoming a new, independent, and totalizing genre (that could absorb all other art forms), is being incorporated as an enriching experience by artists who continue to work in their traditional genres. Despite this failure, those of us who think about the possibilities of creating or discovering it, believe that some valuable conclusions can be drawn.

The broadening of the notion of a work: The traditional temporal and spatial demarcations in which the work of art develops—theater, plastic arts, music, and film—are now open and discontinuous. A work can last fifteen seconds or twenty-four hours (Vostell); it can take place in five different points of a city or in three cities at the same time (Kaprow). In the traditional media—a book, a painting, a theater piece—unity is achieved through a plot and the unitary material characteristics of the work. The Happening, on the other hand, is an “open work” in that it literally opens relationships of time and space and different levels of materiality with which it works. In addition, and this is part of its mythology, the Happening attempts to modify the relationship between the spectator and the spectacle. It is not about hurling lettuces and chickens. It is about achieving unmediated communication, or communication with as little mediation as possible. This occurs on levels as various as those having to do with modes of behavior, called “performing,” to the placement and roles of the spectator. That’s where the advantages end, since the idea of communicating with a minimum of mediation converts the Happening into an exclusive and elite show: Rauschenberg and Oldenburg themselves are onstage to perform a Happening two or three times for two hundred friends, and all this in a city of twelve million inhabitants.

At this moment when the world is being transformed by new technologies and artists themselves are calling for the need for an anonymous, standardized art, the Happening runs the risk of becoming the most individualistic and exclusive art in history. Fortunately, laboratory experiences are useful and today we can imagine an art, collective in its creation and its reception, of the mass communications media. “As growing technologies began creating new environments, man became aware of the arts as anti-environments or against-environments, giving us the means for perceiving the environment itself. Because, as Edward Hall explains in The Silent Language, men are never aware of the basic laws of environment-setting systems.7Edward T. Hall, The Silent Language (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1959). [Ed.] Nowadays, new technologies follow each other in such rapid succession that each environment makes us conscious of the next. Technologies are beginning to play the role of art by making us take notice of the social and psychic consequences of technology.”8McLuhan, Understanding Media, p. 65.

The Happening is, in this case, an anti–environment-setting art—its structure being exactly the opposite of that created by the mass communications media. A mass media piece, like our own piece, summarized earlier, is therefore an anti-Happening, since the Happening is a medium of the immediate, while “mass communications media is a medium of whatever is immediate in the mediatizing of the object.”9The two quotes of Masotta are taken from his seminar on avant-garde art and the information media, given at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella in 1966._ [It is unclear which other quote he is citing as Masotta’s. Ed.]

But isn’t it fortunate that artists—who in a bourgeois society went from total marginalization to integration on the condition of rendering their messages useless—can make art that will be positively social from the very moment of its conception?

On Happenings, Happening: Reflections and Accounts

By Eduardo Costa, Oscar Masotta, 1967

Publication: Originally published as “Sobre Happenings, Happening: Reflexiones y relato,” in Oscar Masotta et al., Happenings (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1967)

Language: Spanish

When we gathered together in April of 1966 to plan a cycle of Happenings, some of us already questioned the validity and novelty of the genre. We were not sure that it would be possible to improve on manifestations that had taken place in the United States, their country of origin. Even though the genre was universalized and, on the other hand, the boundaries of its concept are fairly imprecise, we were not certain we would not repeat, in a watered-down fashion, something that had already been done.

Later on, toward the beginning of July, when we informed the press about a Happening that had not taken place, we were already thinking of another type of work: of working in the “interior” of the mass communications media. In any case, in a country where everybody was talking about Happenings with scarcely having seen any, it was not a bad idea to try them. We began by informing ourselves about them, and soon we had familiarized ourselves with the work and names of Allan Kaprow, Carolee Schneemann, Michael Kirby, Samaras, La Monte Young, Wolf Vostell, Robert Whitman, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Bazon Broch, Charlotte Moorman, Nam June Paik, Thomas Schmidt, and Joseph Beuys. The more information we gathered, the stronger grew the impression that the possibilities—the ideas—had been exhausted. The idea not to do an original Happening, then, and instead collect various Happenings that had already happened into one Happening suddenly seemed more important to us. What is more, the Happenings could be selected with an intentionality. Soon we decided on one: we would make a Happening that would bring together a group of Happenings of different styles, a grouping that would work as a commentary on the history of Happenings. It would not be a complete history, but certain “marks” would be clearly highlighted. We would be didactic. Further, that history of the Happening would be a Happening made up of Happenings. What made it a true Happening, in the sense that this is what differentiates it from theater, was that various Happenings or fragments of Happenings presented simultaneously or successively constitute a Happening, while several works or fragments of theatrical works do not constitute a theatrical work. Like some animals, Happenings continue to live when divided into segments, and it can be done in such a way that the parts group together, as in the biological world, into colonies.

A colony of Happenings and history of the Happening: however, the title we chose did not have anything to do with either idea. We had found another that managed to motivate us positively. The title selected was About Happenings, with the stress on the first word; in other words, the idea of a commentary, an account. We would make use of a Happening to tell about others. Our Happening would be a mediator, like a language of absent events, already nonexistent, in the past. The events, the facts inside of our Happening, would not just be facts, they would be signs. Put another way, we were excited, once again, by the idea of an artistic activity put onto the “media” and not onto things, information about events and not the events themselves.

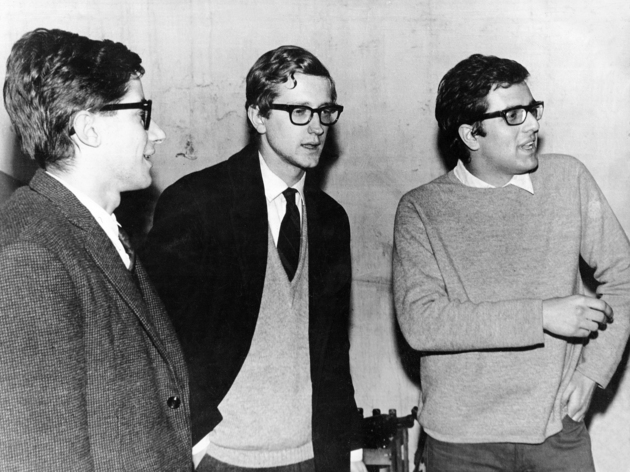

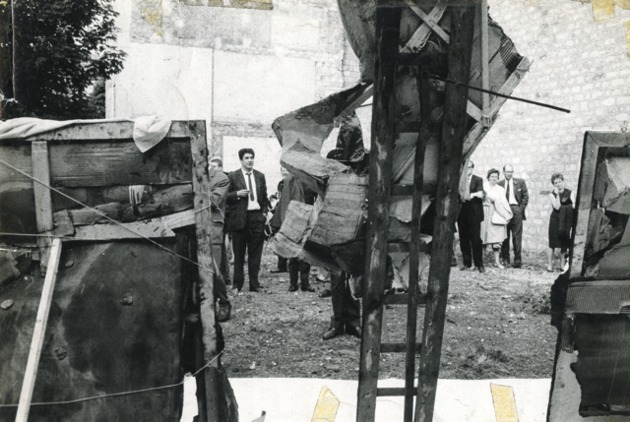

That is when we formed a group: Roberto Jacoby, Eduardo Costa, Miguel Ángel Telechea, Oscar Bony, and Leopoldo Maler. Masotta would also collaborate. Then we chose the Happenings that we would re-present, and that we believed summed up a historical progression. 1. Meat Joy by Carolee Schneemann 2. A Happening by Claes Oldenburg (we do not know its title) 3. Autobodys, also by Oldenburg 4. A Happening by Michael Kirby (the title of which we do not know) For practical reasons (place, time), the chronological order in which they were performed did not follow this order. The actual order was 3, 2, 4, 1.

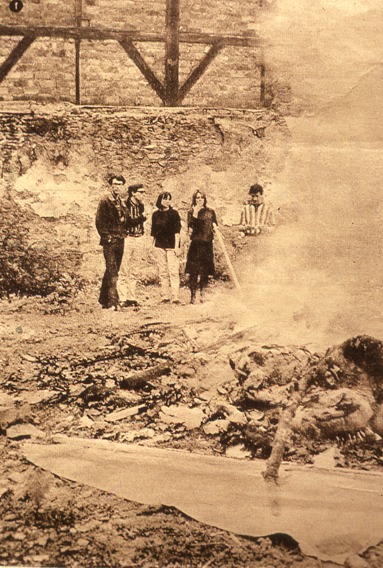

The first Happening, Oldenburg’s, was refined and speculative, mildly mortifying for the audience, and took place inside of a show hall, which was also its theme. Autobodys was rougher, spectacular and noisy, with mechanical elements—vehicles were indispensable—and took place in a parking lot. Carolee Schneemann’s piece talked about meat, with human bodies mingling with fish, chickens, strings of sausages; it fit into the sensual current now dominant in France. It was brilliant and showy, and transmitted a certain old beauty that made it appealing to lovers of images. Kirby’s piece was the one we felt was closest to us: there were no plastic images there—or at least they were in the background—but rather mechanical means of information: film, photographs. It was an information media Happening, although the information in it was not mass-oriented.

We had the following information at our disposal to reconstruct the Happenings: In Happenings, Michael Kirby’s book (London: Sedwick and Jackson, 1965), we found the original script of Oldenburg’s Autobodys, from which we reproduce some excerpts below. [Not included in this anthology. Ed.] The original script of Meat Joy can be found in the magazine Some/thing (New York, winter of 1965); also in this publication are to be found the “Notes to Meat Joy,” a collection of images and witticisms jotted down by the author that, together with “French Lessons” (Carolee Schneemann was in France at the time), serves as the basis for the sound recording that accompanies the actions. We also transcribe here what the artist calls the Happening’s “Sequence Diagram,” that is, its script. As for Oldenburg’s other Happening, we had the account that was published in Art News (February 1965) and we reproduce it here in its entirety. Finally, with regard to Kirby’s work we had Masotta’s account, which can be read on pages 163–65 of this volume.10See pages 193–94 of the present anthology for Masotta’s description. [Ed.]

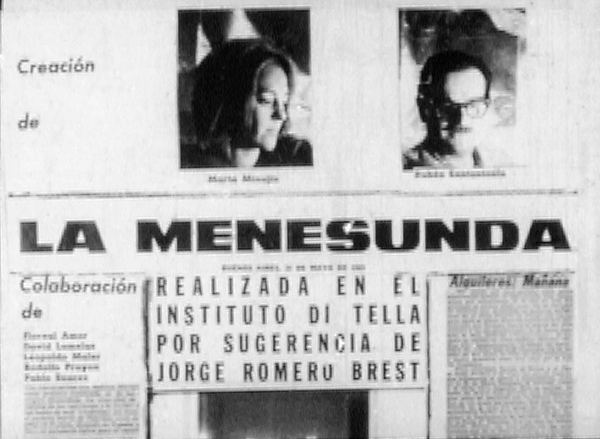

About Happenings was planned to be part of a cycle of two lectures and three Happenings organized by Masotta and to be performed at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella: it would be the last performance of the cycle. Internal difficulties with scheduling in the performance space of the Institute caused us to postpone and change the date of the event three times. We intuited that these delays would further arouse the curiosity of an audience not accustomed to seeing Happenings, a curiosity piqued at the time in Buenos Aires by the information media’s propagandizing of the term. We ordered posters in which we answered the voiceless and intentional misinformation propagated by the media, changing the title of the Happening. The posters read, “Happenings, Happenings, Happenings.” The result: at nine o’clock p.m. on December 6th, over five hundred people assembled in the foyer and at the doors of the Institute.

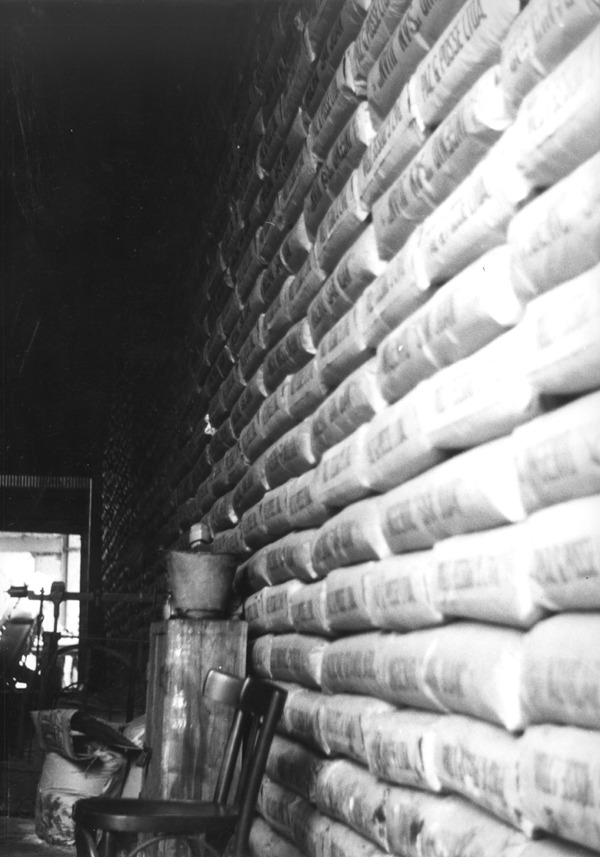

Only two hundred of the five hundred were able to enter. Meat Joy was performed on the premises, in a warehouse inside the Institute, the floor of which was only designed to bear the weight of that many people. At first the public had no problem with this. Two hundred people entered the theater and we gave instructions for them to go to a parking lot located less than a block from the Institute on Paraguay Street, between Florida and Maipú. The members of the audience who were in the theater, following the instructions, headed for the parking lot, although followed by the part of the audience that had not been able to enter. Then five hundred people invaded the parking lot on Paraguay Street: Autobodys then became something else. The audience took up the length and width of the parking lot, and the cars had to enter slowly, making their way through the people. The lights and cameras of [the television shows] “Sucesos Argentinos” and “Telenoche” created a small stir around each action. All attention was concentrated wherever there was a spotlight. The actions—that tried to follow the script as faithfully as possible although there was no cement mixer—were only visible to those who were close up. Autobodys required a wide open space so that the vehicles could glide over the floor, but it was performed in a space that was completely packed, on a floor supporting over a thousand human feet. When the actions were over, the spotlights were turned off and the people went back to the Institute.

Immediately there were difficulties at the entrance. Everybody wanted to get in, and those who had tickets had to struggle to filter through the crowd pressing against the doors of the theater. Upstairs everything was ready to start Oldenburg’s second Happening, for which we followed all the instructions we had read (we lacked only the doctor with his little mirror and his actions). The audience, arriving slowly and in clusters due to the situation created at the door, seemed nervous and upset. Pretty soon after they had all entered, the prohibition against sitting down was broken and the audience occupied the seats.

Meanwhile, from the theater’s booth we explained the idea of the Happening over a microphone. We gave information about the authors and the actions of each of the original Happenings and we said—which was the truth—that it was not our intention to repeat Happenings but to produce for the audience a situation similar to that experienced by archeologists and psychoanalysts. Starting from some remains that had been conserved to the present, they had to reconstruct a past, the original situation.

Once the prohibition of sitting was broken, the Happening ended. With the people sitting in the seats we soon started our enactment of Kirby’s piece. Of this work we only conserved the essential. We filmed the team of creators at the Moderno Bar, which is within walking distance of the Institute, and then the same group inside the Institute. We combined the film with slides of the same people—ourselves—and with the repetition of a scene live at one of the bar’s tables on the stage of the theater. A sound recording superimposed on the film and the slides reproduced a conversation that accompanied the visual exhibition. Since the audience realized immediately that the authors of the Happening were the people they were watching on the screen and since a feeling of discomfort and disagreeableness was prevailing, they tried at first to behave negatively. But the attempt at mockery was quickly quelled by the taped dialogue, in which at least one of the audience’s reactions was anticipated: that people would attend the Happening. The film went on to say it didn’t believe much in Happenings, that the genre was dead or out of date, and that in spite of this, the public would attend. From that point on, the people were hooked and gave their full attention to the rest of the projections. The last was a filmed rehearsal of Meat Joy. The audience was told they were viewing a 16mm projection of a rehearsal of the same Happening they were about to see. In the rehearsal the performers did not use fishes and chickens, but any old object, balls, pieces of wood. In a daring shot one of the performers slowly and suggestively bit and licked a piece of wood. The audience was then invited to climb the stairs toward the warehouse where Meat Joy was to be performed.

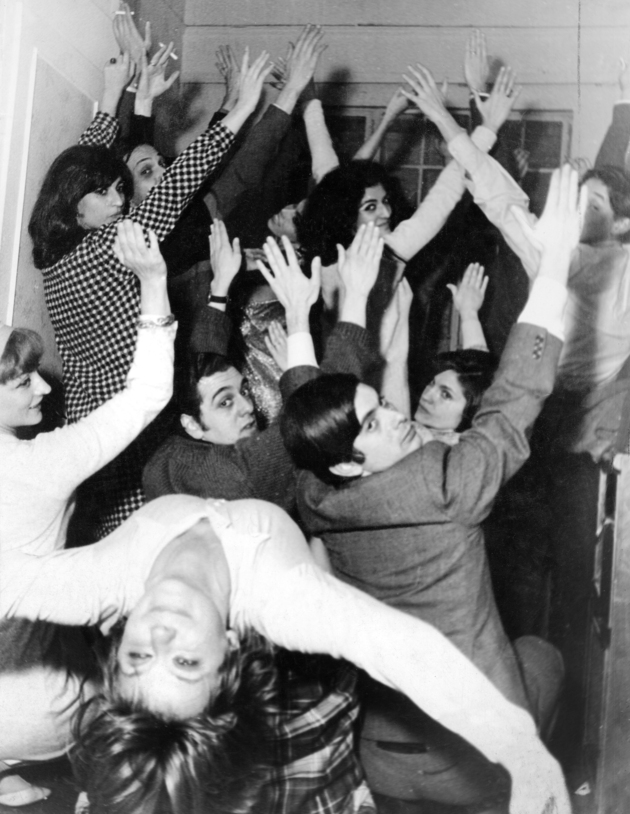

From the beginning, the audience followed the actions with fascination: The undressing, the entwining of bodies, the paint, the confetti, the real presence of the chickens and the fish, the smell. Perhaps the photographers went a little crazy. They mingled with the performers and there is no doubt they became part of the spectacle. It would not be a mistake to think they believed themselves to be witnessing something sensational. Although perhaps they realized, in some way, that it wasn’t all that sensational. In any case, they did what they could to make it so. We are referring to the cameramen of “Sucesos Argentinos”: within a week a number of pretty good shots of _Meat Joy _were aired on the news, accompanied by the mellifluous, policelike voice of the commentator who called for the “authorities” to intervene before representations of this ilk began to spread.

An Art of Communications Media (manifesto)

By Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escari, Roberto Jacoby, 1966

Publication: Written and delivered as a lecture in 1967. Originally published as “Después del Pop: nosotros desmaterializamos,” in Oscar Masotta, Conciencia y estructura (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1969).

Language: Spanish

“He devoured her with his eyes.” This sentence and so many other similar ones illustrate quite well the enthusiasm common to realism and idealism according to which knowing is eating.” Jean-Paul Sartre

“The idea moving the masses today is called materialism, but dematerialization is the defining characteristic of the epoch. For example: correspondence grows, so the number of letters, the quantity of writing paper, the mass of material consumed expand, until relieved by the telephone. Again, the network and material of supply grow until they are relieved by the radio. Matter diminishes, we dematerialize, sluggish masses of matter are replaced by liberated energy.” El Lissitzky

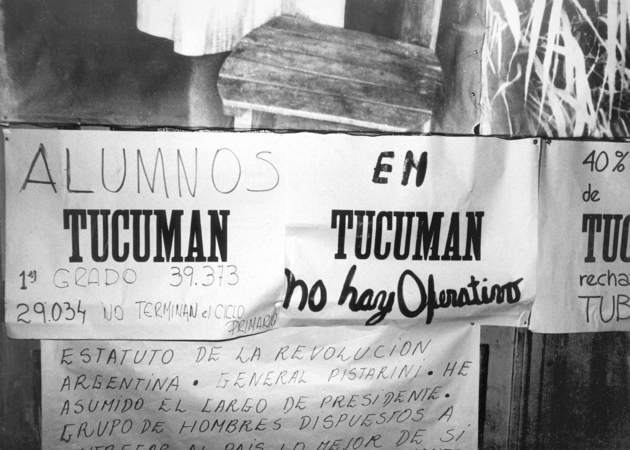

1. The Word “Happening” in the Mass Media We are not a country of Happening-makers, despite the fact that one of the genre’s founders, Allan Kaprow, referred to Argentines as such a year ago (I don’t remember exactly where: Art News, Artforum?). At that time relatively few Happenings had been made in Argentina. Nor were many made afterward: 1966, quantitatively speaking, was not all that fruitful. To be exact, only two Happenings took place among us last year. We should add to that number just two more “works” of uncertain classification whose authors refuse to call Happenings, plus a work whose classification is less uncertain and that was conceived as a literary work and that could undoubtedly be called a Happening. Add to this the work of an American, Bob Whitman—a film that Marta Minujín brought to Buenos Aires, Prune Flat. The film was part of a “work” in which the bodies of three women live on stage served as a screen onto which the film of the bodies of the women was projected.11Detailed information about Happenings and works carried out in 1966 can be found in Oscar Masotta et al., Happenings (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1967). [See also pp. 180–85and 191–206 of the present anthology. Ed.]

Nevertheless, though the Happenings actually made numbered very few, the word “Happening” spread through the dailies and magazines of Buenos Aires over the course of 1966, from magazines of a certain level of “style” and/or “seriousness” such as Primera Plana and Confirmado to pretty lowbrow (sensationalist and with little written information) publications like Así. Spanning dailies like La Nación and La Prensa to La Razón and El Mundo, political articles to humor columns, the word invaded the comic strip and finally reached the billboard. This is a strange phenomenon given that if it does not correspond to the facts (that is, to the Happenings effectively carried out), it appears to spring from nothing. Nor does it make sense to try to understand it by thinking of the dates, since around the time that a few Happenings actually were taking place at the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella the quantitative growth phenomenon of the word was already quite advanced.

How to explain the phenomenon? There is a sort of explanation that has not appeared in print but is heard around and is, to my mind, rather abominable for two reasons. Firstly, because it is complicit with what the word means within the mass media boom (something irrational and spontaneous, trivial and festive, slightly scandalous). Secondly, because of the ideological charge of an explanation that consists in affirming that Argentine “reality” (I also loathe this sort of use of the word “reality”) is really not very serious, that the explosion of the word in the press is in some way a positive phenomenon because it somehow represents a becoming aware of our lack of seriousness. Just imagine: the vicissitudes of political power, the circular succession of economic teams. And what of the ridiculous seizing of the Falkland Islands (known in the Spanish-speaking world as Islas Malvinas) by an ex-actress and a few young extremists? I would say the answer is nothing. Especially if the point is to make comparisons: the domestic and foreign politics of Argentina are no less serious and more scandalous, nor more serious and less scandalous (perhaps less scandalous) than those of any other Western nation. On the other hand, it would be difficult for Argentines to give ourselves the politics we want. The steel limits of an internal and external economic and social structure determine and decide for us and without us the “reality” that is only ours because it is foreign.

In any case, I believe that the explosion of the word can perhaps be explained, or at least understood via a certain hypothesis, incomplete no doubt with regard to the facts it deals with, but at least, sensible. Firstly, in no case do I remember having read the word without it referring in some way to the real facts, that the “Happenings” are products of a certain type of avant-garde artistic activity. This reference to artistic activity, however vague, indicates a certain relationship: the presence of a certain significant distance. And it condemns this distance or void that exists between the products of mass information and avant-garde artistic activity.

On one hand the void signifies the unresolved situation in contemporary culture between the elite and the masses; but the slightest consideration reveals a real shortcoming in Argentina: above all, the lack of competent criticism to accompany avant-garde production, especially in the visual arts. I refer, concretely, to the lack of written material. The only ones in Buenos Aires who have the information to talk about the most contemporary production ([Jorge] Romero Brest, [Aldo] Pellegrini, Germain [Germaine Derbeq], [Hugo] Parpagnoli, Samuel Paz) rarely write for publications other than catalogues, and when they do write for specialized magazines, they are magazines that are not published in Spanish. In one of last year’s issues of Art and Artists, the English magazine edited by Mario Amaya, I remember reading an editorial that discussed the difficulty of distinguishing these days between a journalist and an art critic. The high level of everyday criticism makes the distinction difficult. In this regard, alas, Argentina is not England, or the United States, or France. On the contrary, in addition to the lack of specialized criticism in Argentina, the everyday criticism is ill-informed and adverse. Primera Plana and Confirmado are no exceptions. The critic here rarely commits himself. He is more interested in displaying information he does not have or has obtained hurriedly than in simply using the information he does have to aid in the comprehension of the work.

But these reflections do not explain the explosion of the word, which surely would not have occurred without a certain anxiety—let’s call it that—or a certain predisposition on the part of the mass audience. Interesting phenomenon, to my mind, and positive in that it points to the fact that whatever the distance between an aesthetic production intended for an elite audience and a broad audience, that distance is never absolute and there are always some points of contact or some sort of breaking up of the distance. Now, it is important to understand also that the spread of the word (and all the mistakes regarding its meaning) is not due to the “ignorance” of the mass audience, for it is not the receptors of mass messages who compose the messages, but rather the journalists. That is to say, a certain kind of intellectual worker who not only bears the pressure of tensions like those borne by those for whom he writes, but also the theoretical tensions of the intellectual world and the surrounding environment of artistic production.

One would, then, have to think about this situation in particular. I would say that in Buenos Aires one of the coordinates falls on the activity of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella for the yearning this activity could not help but provoke in groups that are originally or naturally removed from it. Whatever the value or the judgments made on the works promoted by the Visual Arts and Audio Visual departments at the Institute, there is no doubt that they contrast with a certain milieu the bulk of whose artistic production was created inside the traditional canon. There is no “underground” in Buenos Aires, and in a world in which the artistic production is not very big, the “institutionalized underground” of the Institute could not but exert pressure on that milieu.

But what is happening in the rest of the “field,” in the majority of the cases? Let us reflect briefly on what is happening in Argentine film. The best films produced among us (works by [David José] Kohon, [Fernando] Birri, and Lautaro Murúa) did not go technically beyond certain more or less Neorealist aesthetic strategies. And beyond the searches of [Manuel] Antín with regard to time and the thematic searches of [Rodolfo] Kuhn, there was no progress among us toward a nouvel vague cinema, for example, or any major avant-garde propositions. Once the city had been explored as a theme, and once a certain testimonial description had been achieved (Alias Gardelito and Tres veces Ana constitute the best examples), young directors generally filmed rather little. The situation can be explained in large part by the economic difficulties linked to production and the uncertain loan policy enforced by the Instituto Cinematográfico Argentino. But looked at the other way, it would be difficult to say that young directors do not film much solely because of money and financial difficulties. I believe that the current impasse in Argentine cinema expresses, at this level, an aesthetic impasse. To give the matter yet another twist, it is not that young people have nothing to say but that perhaps they are beginning to have a sharp consciousness that tells them that the issue is not what is said, or even perhaps the way in which it is said, but in the characteristics of the “medium” at hand to say it with.

To put it another way, at this moment in the process of contemporary art, at a time when not only are new “genres” of expression appearing, like the Happening, but when the very idea of “genre” as a limit seems precarious or perishable (theater mixes its techniques with those of film, dance blends with painting, film shows the strong influence of the comic strip), it becomes increasingly impossible to remain indifferent to this small proposition of all avant-garde work or exhibitions (and at the same time, to not take seriously the very idea of avant-garde). The problems of contemporary art reside less in the search for new content than in research of the “media” for the transmission of that content. “Media” here means generally what it means in advertising jargon: the information media (television, film, magazines, and newspapers). And if there is talk now of not concerning oneself with content, it does not mean that avant-garde art is moving toward a new purism or a worse formalism. What is occurring today in the best pieces is that the contents are being fused to the media used to convey them. This concern, then—demonstrated explicitly for the first time by the Pop artists—is inseparable from a true sociological concern, that of a new way of returning to “content.” No filmmaker today could permit himself, even if he tried—faithful still to the Neorealist spirit—to comment on or “show” the social “reality” of a city. He would be too late, because it has already been remarked on and remarked on again by the dailies, newspapers, radio-phonic “works,” television, photo-novels, and advertising. The contemporary artist cannot help but become aware of the appearance of these mass phenomena that in some way throw his own work off kilter. And we already know the tactics with which he is responding.

On one hand, this is being done by proposing images that, like Lichtenstein’s, are not “from reality” but rather images of images. And on the other hand, through a radical reflection on the material characteristics of the aesthetic “medium” that is being worked with. Today the proposals of an outdated criticism that did not tire of making pronouncements like “this is painting, this is not,” “this is theater and not film,” “this is culture and that is not,” are contrasted with the idea of making works with materials and techniques taken from different genres, the idea of an area of aesthetic activity where it is possible to mix the strategies and the “media.” In short, the idea of the work of art as “hybrid.”

In summary, the explosion of the word “Happening” in the mass media information of Buenos Aires may perhaps be due to reasons that still have to do with issues like aesthetics and the history of the works. They are the result of a certain degree of complication among these types of factors: 1. The lack of serious criticism on an everyday level 2.

The lack of a specialized criticism in specialized publications that could have an influence on everyday criticism 3.

A certain positive restlessness on behalf of mass audiences that is only satisfied by an indifferent criticism 4.

The need—without a doubt whatsoever—for the groups producing art to find new aesthetic formulas and problems 5.

The way in which these needs, combined with the existence of an avant-garde production on the level of the visual arts, are projected on individual journalists, that is, those responsible for the explosion of the word

It is not surprising that the direct, personified, concrete emitters of mass messages effectively constitute the terminal point in a series of chain reactions whose mechanism operates similarly to what psychologists describe as ambivalence: the negative and positive evaluation of the same object. This might be the reason behind that atmosphere tinged with a slightly spicy air associated with the idea of sex and parties that has often accompanied the word Happening when, beginning last year, it has appeared in print in the dailies and magazines of Buenos Aires.

2. The Avant-Garde and Works of Mass Information A cycle of lectures and Happenings I executed at the Di Tella Institute in October and November of 196612The cycle comprised two lectures and two Happenings. One of the lectures was given by Alicia Páez, and I performed one of the Happenings. The other was planned and coordinated by a team made up of Roberto Jacoby, Eduardo Costa, Oscar Bony, Miguel Ángel Telechea, Pablo Suárez, and Leopoldo Maler. links my name to the word Happening. Despite the spread of the word in the mass media, I should add that I am not a Happening-maker. I mean, in the same way that I am not a musician, or a painter, or a sculptor, or an actor, or a theater director. I have not committed even the bulk of my activity or my future to any of those activities. I wish to add, furthermore, that I do not believe in Happenings. Now, I think I should explain what I am saying when I say I do not believe in Happenings, but it is difficult. Sometimes it is simply not the time or place for explaining everything. I will say in any case that I do not believe in Happenings just as I do not believe in painting and theater. And I can discern in the reader a slightly sarcastic and amused fury that will cause him to exclaim: we have here “an avant-gardiste”! Very well, I will not contradict that. In art, I believe, today one can only be of the avant-garde.

The problem arises when one tries to define the avant-garde. Although it is not difficult, I will not attempt that definition here. More than offering definitions, my intention now is to give some account of events and complete the account with a few indications and some reflections. I will say that an avant-garde work must have at least these four properties:

a. That there be recognizable in it a certain susceptibility and completed information about what is happening on an art-historical level, that is to say, about what is happening in art in reference to what has been done before and to what is perceived should happen afterward. In this way, the avant-garde consists in a postulation that states that the work of art exists within a historical sequence of works, and that that sequence is governed by an internal necessity. A quote from Henry Geldzahler expresses this property succinctly: “This is instant art history made so aware of itself that it leaps to get ahead of art.”13Quoted from Henry Geldzahler, participant in the “Symposium on Pop Art” organized by The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Published in Arts (April 1963): 37.

b. That it not only open up a new range of aesthetic possibilities (that is—how does one say—that it be an “open work”) but that it simultaneously, and in a radical way, negate something. For instance, the Happening with regard to painting,14See Allan Kaprow, “Experimental Art,” Art News (March 1966): 62. or the Happening with respect to traditional theater.15See Michael Kirby, “The New Theatre” Tulane Drama Review (New York) 10, no. 2 (winter 1965): 15.

c. That this relationship of negation (with regard to what the work negates of that which has preceded it) not be whimsical, but that it reveal something fundamental about the very core of what is negated. In this way, the passage through or overcoming of theater or painting by the Happening would be a “logical consequence”6 of something already latent in theater or painting demanding to be manifested.

d. (This point is perhaps harder to understand and accept immediately; let us say it is more controversial.) That the work question, with its own radical negativity, the limits themselves of the great traditional artistic genres (painting, sculpture, music, etc.). For instance, the Happening with regard to those traditional media themselves. According to this property—as I understand it—Picasso never would have belonged to the avant-garde since the “plastic arts” of the twentieth century would have had only one outburst (the only one that would effectively stretch the boundaries of the genre): the Dadaism of the second decade of the century (and its “revival” during the mid-1950s with Pop art and French Neorealism, which is when Happenings appeared historically). In this view the avant-garde of the century is made up of just a few names: Satie and Cage, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Warhol, Duchamp and Schwitters, Yves Klein, Allan Kaprow. And one would have to add the name of one Surrealist, René Magritte.

On the basis of these considerations one might reach a hurried conclusion: that today only the Happening, this hybrid of genres, is avant-garde. Very well, that is not what I believe. On the contrary, from my position I can affirm that there was something within the Happening that allowed us to glimpse the possibility of its own negation, and for that reason the avant-garde is built today upon a new type—a new genre—of works. These works might be termed “anti-Happenings,” but there is a problem inherent in that designation: it makes a completely new aesthetic manifestation depend upon a genre, like the Happening, that is no longer new. To get to the point, this new genre of artistic activity that appeared in Buenos Aires in 1966 already has a name: “Art of Mass Communications Media.”16The creator of the genre is, without a doubt, Roberto Jacoby (see Oscar Masotta et al., Happenings), and that is in its purest form. This genre of works, to my mind, contains within it nothing less than everything one can expect from that which is greatest, most profound, and most revelatory in the art of the coming years and of the present. As for Marta Minujín’s work with sixty televisions that she carried out at the Di Tella Institute last year, it still remains hybridized with the idea of “environment-making,” even though it went beyond it. I can attest that it fulfills the basic requirements for describing a field of artistic activity; that is, it effectively constitutes an artistic genre. This is confirmed, on one hand, by its capacity to produce “objects” for aesthetic contemplation and, on the other hand, by the fact that it concretely delimits the “material” with which it is possible to construct a particular and precise kind of work. Just as the “material” of music is a certain sonorous material or the continuum of auditory stimuli and bronze, wood, marble, glass, and the new synthetic materials constitute the “material” with which and upon which it is possible to make sculptures, the “works of communication” also define their own area of “materiality.” _The “material” (“immaterial,” “invisible”) with which informational works of this type are made is none other than the processes, the results, the facts, and/or the phenomena of information set off by the mass information media. (Ex. of “media”: radio, television, dailies, newspapers, magazines, posters “panels,” the comic strip, etc.).17I distinguish thus between the “aesthetic object,” the “media” in which the work is made, and its “material.” In order to define precisely the field of works of mass communication, one must not confuse the “media” with the “material” of the work. This distinction brings with it a certain obscurity, but its meaning can be clarified quite a bit if one thinks of advertising. The “material” with which any campaign works is constituted by the consciousnesses of the subjects at whom it is directed: the “material” is then, for example, the so-called “phenomena of persuasion” or rather the “effect.” So the “media” is the instrument for reaching them: the posters, television, the stills. Now, between a work of advertising and a work of mass communication there are, nevertheless, differences with regard to the “aesthetic object.” A commercial can be “beautiful” and those with modern tastes and sensibilities will easily recognize it. But the “object” of the mass work also has a lot to do with that beauty. What is perceived has more to do with certain effects of intelligibility that are achieved through certain “transformations” of the usual structures of mass communication. The example of El mensaje fantasma [The Ghost Message], to which we shall refer shortly, may serve to clarify these difficulties.

3. A New Cycle It was in this spirit and with these ideas in my head that I developed a new cycle, also to be carried out at the Instituto Di Tella and which would comprise (did comprise) a Happening, the title of which was El helicóptero (The Helicopter), a communicational work (or “anti-Happening”), the title of which was El mensaje fantasma (The Ghost Message), and an explanatory lecture that I called “Nosotros desmaterializamos” [“We Dematerialize”]. The purpose is easy to discern: to compare a communicational work and a Happening to allow for the comprehension of the distinctive characteristics of the operations and “materials” that constitute them. The cycle proposed at the same time an “anti-optical,” anti-visual aesthetic: the idea of constituting “objects” but with the goal of speaking not to the eyes, but to the mind. The title of the communicational piece commented on the tension of the search for immaterial materials, for anti-things, if you will. As for the title of the lecture—in which I tried to explain in a less orderly manner what I am trying to explain now—I took it from a brief article by El Lissitzky, the Russian Constructivist, shrewdly exhumed18I say this with perspicacity since the ten pages by El Lissitzky are more than thirty years ahead of Marshall McLuhan’s “thesis.” in a recent issue of the New Left Review, the journal of the independent English Left. Of all El Lissitzky’s nervous and lucid paragraphs, one in particular fascinated me. It can be read in the epigraph to this essay. . . .

( . . . )

6. The Ghost Message My intention was not only to make a Happening, but to point out the difference between two genres of works, to exemplify the difference between the Happening and “media art.” I wanted to point out at the same time that the idea of making works of the latter type was already indicated in Happenings and that the passage emerged as a “logical consequence.”

El helicóptero showed the communication vocation of Happenings, given that its design (watches, spaces) led to a final situation that required an oral account. One could say that El helicóptero was a communicational work, but the communication there was oral and not of the masses. The field of the Happening, requiring the concrete presence of the people in the audience, coincides with the field of perception, that is to say, with the field of stimuli open to the senses. Whatever the function assigned to the audience,19With respect to the function of audiences in Happenings, see Alicia Páez, “El happening y las teorías” [“Happenings and Theories”], in Masotta et al., Happenings.[This was footnote 28 in the original. Ed.] the presence or immediate belonging to the place where the events take place is required. In this way, Happenings have emerged as prolongations of “environment-setting works,” of “environment-settings,” in which the aim is to envelop the subjects in the audience in direct media and sensory stimuli (smells, colors, etc.).[^11] And if there is a difference between an environment-setting and a Happening, since at least in the latter the audience can be moved from one place to another, both types of works require the quantitative determination of the audience. One could not conceive of a Happening, for instance, in which no audience was called to “participate”; that is, ultimately, one could not imagine a Happening without “spectators.” But one can conceive of and carry out another type of work with that condition. The proof is that they can “begin,” contrary to Happenings and theater works, without the need to gather an audience.

El mensaje fantasma (The Ghost Message) was a good example. The 16th and 17th of July I had posters put up in a central area of Buenos Aires (from 25 de Mayo to Carlos Pellegrini and from Charcas to Lavalle) bearing the following message: “This Poster Will Be Broadcast on Channel 11 Television on July 20.” Now, for July 20 I had purchased on Channel 11 (through an advertising agency) two spaces of 10 seconds each during which the channel’s announcer said: “This medium announces the appearance of a poster the text of which we are now projecting.” A sign appeared simultaneously on the screen on which one could read, in another typeface, the very words printed on the poster: “This Poster Will Be Broadcast on Channel 11 Television on July 20.” I should not like here to act as a critic of my own work. Nevertheless, these characteristics may be highlighted:

a. That the media with which the work was carried out (and this was clearly in line with Pop propositions) was the same as that used in advertising.

b. That the audience for the work was clearly undefined. Within a mass audience the actual audience could be anywhere between a few or many subjects.20“The term ‘environment-setting’ refers to an art form that completely fills a room (or an interior space), that envelops the visitor and that uses any type of materials, including lights, sounds and colors.” Words, op. cit. [This was footnote 29 in the original. Ed.]

c. That with its similarity to certain advertising “works,” with the beginning of an unknown campaign, and its difference from advertising, given that there were no later steps, the work revealed its “finality without an end.”

d. That its specific purpose was to invert the usual relationship between the communications media and the content communicated. Here, and in a reciprocal and circular way, each medium revealed the presence of the other and its own presence was revealed by the other.

An Art of Communications Media (manifesto)

By Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escari, Roberto Jacoby, 1966

Publication: Originally published as “Un arte de los medios de comunicación (manifiesto),” in Oscar Masotta et al., Happenings (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1967)

Language: Spanish

In a mass civilization, people are not in direct contact with cultural events; rather they are informed about them via the media. For example, a mass audience does not see an exhibition, attend a Happening, or go to a soccer game, but it does see footage of the event on the news. Actual artistic events are no longer important in terms of their diffusion, because they only reach a limited audience. “Distributing two thousand copies of an artwork in a big modern city is like firing a shot in the air and expecting pigeons to fall,” said Nam June Paik. In the final analysis, it is of no interest to information consumers if an exhibition took place or not; all that matters is the image of the artistic event constructed by the media.

In the course of coming into being, contemporary art (basically Pop) sometimes took elements and techniques from the mass media, disconnecting them from their original contexts (for example, Lichtenstein with his comic strips and D’Arcangelo with his road signs). As opposed to Pop art, we intend to create the work within those media. So our plan is to send the press a written and photographic report about a Happening that did not occur. This false report will include the names of the participants, an indication of the time and place of the event, and a description of the performance that we are pretending occurred. The photos of the supposed participants will be taken from other situations. Thus through the transmission of the information, the means of “performing” the nonexistent event, and the differences that arise between the various versions of the same event presented by each media channel, the work acquires its meaning. A work that begins to exist exactly at the moment the audience becomes aware that it’s already over. So this is a triple creation: —writing a false report —transmission of this report through the media21The message varies depending on the material features of the channel that transmits it. “The medium is the message.” (McLuhan)—reception on the part of the spectator who constructs—from data received and based on the meaning the data acquires for him—the dimensions of a nonexistent reality that he believes to be true.

Thus we are taking a key characteristic of the media to its logical conclusion: the unmaking of the objects. In this way we are privileging the moment of the work’s transmission over the moment of its creation. Creation consists of subordinating construction to transmission.

Today, the work of art is a set of results of a process that begins with making the work (traditional) and continues until that work turns into material transmitted by the mass media. Now we are proposing an “artwork” in which the moment of creation disappears, because this is a way of commenting on the fact that these works are really a pretext to set off a round of media activity.

From the audience member’s point of view, there are two possible readings of this kind of work. On the one hand, there’s the reading of the audience member who trusts the media and believes in what he sees; on the other, that of the audience member in the know who is aware of the nonexistence of the work reported on.

This opens up the possibility of a new genre: a “mass media” art in which what is important is basically not what is said; rather the medium itself becomes the subject. In addition to preparing prospective recipients of the second reading, this “advisory” puts some readers on notice and constitutes the first part of the work we are announcing.

Creation of the First Work

By Eduardo Costa, Roberto Jacoby, 1967

Publication: Originally published as “Realización de la primera obra,” in Oscar Masotta et al., Happenings (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1967

Language: Spanish

In May 1966 Roberto Jacoby had planned to create an exhibition that would be only the report of an exhibition. In other words, he planned to present in a gallery only the catalogue of the exhibition, describing the works. It would include all the features of the most complete catalogue possible: critics’ opinions, sketches of the work, etc. These elements, all false, would complete the falsification of the very exhibition that had given rise to the catalogue, while confirming its apparent reality.

Before carrying out this project, Jacoby thought about creating a work (a Happening) in which the reality of the event would be replaced by a report about it, adding the idea that said report would be sent to the mass media. In this way, he would “change the place of the moment of creation, situating it within the media.” (Lawrence Alloway)

To record this idea, Roberto Jacoby and Eduardo Costa drafted a manifesto in which they proposed “a media art” and made a first attempt at analyzing the work they had proposed. By the time the manifesto was published, Raúl Escari had signed it as well, having contributed to its final draft in July 1966. The need to record the idea by publishing the manifesto was of no help to the process of creating the work because some journalists became aware that the report that was going to be submitted to them would be false, and they avoided publishing any related news.

The first step in creating the work announced in the manifesto on “media art” was drawing up a list of personalities, mythical figures known in some way through the media. Moreover, they would be people who could get excited about the idea and were easily accessible. Of all those interviewed, only two people refused to participate. In planning the task of persuasion, first we tried to solicit the most important names, counting on them to be enthusiastic about the idea and support us. In this way, by backing the project, they would help us convince the public of the “seriousness” of an undertaking based on lying to people less aware of the possibilities and strategies of contemporary art.

While we tried to suggest to all the participants that we were creating an “artwork,” we had to retreat after our first attempts to explain ourselves. At this stage of our work—a “material” stage, for us, people were showing total resistance, qualified by various degrees of friendliness; so we came up with explanations that were more comprehensible. For example, the explanation that we were planning a sociological experiment that entailed a moral critique about the way the mass media functioned. Or we would say that we wanted to play a joke on journalism. Many of these people had experienced the media’s capacity to modify information, and they liked the prospect of getting even. The “creative work” we were doing in this phase was mainly convincing people about our proposal. Once the list was done, we interviewed the people we had identified and asked them to invent their own participation in the supposed Happening, which they would have attended and in which each invited guest would have “participated.” We immediately wrote up the activities each participant proposed for himself, in a report that we tried to write in a style familiar to journalists, the press release, but in the driest and briefest way possible. This report was rounded out by a theory we designed to meet the expectations of journalists fairly well informed about the theories that might be developed by two young people involved in creating Happenings. Essential to this theory, which rested on the already mythical idea that a Happening was characterized by general participation, was the experimental nature of our work. We also invented the false name “Total Participation Happening” related to the theory we submitted to the press.

Along with the report, we also sent a set of thirteen photographs taken by Rubén Santantonín in various places: the home of Christian, a stylist; the Walger family home; Avenida Theater; Galanta Studio; Galería Bonino; Norde Shoe Store; Centro de Artes y Ciencias [Art and Sciences Center]; Bar Moderno. The report and photos were sent to various journalists in hopes they would believe they were real and would treat them as if they were any other news item normally sent to them. In most cases, this was not possible. On August 21, the first article written based on our false report appeared in the daily newspaper El Mundo (circulation 300,000).

On August 25, an article appeared in the magazine Gente (circulation 90,000). On August 29, an article appeared in the magazine Para Ti. On September 19, an article appeared in the magazine Confirmado (circulation 48,000). It discussed Happenings in general, describing the genre in accordance with the data included in our report. In October, it appeared in the literary review El Escarabajo de oro (circulation 5,000). On October 30, the first statement refuting the news appeared in El Mundo. On November 1, another statement appeared in Primera Plana (circulation 50,000). On November 10, a statement appeared in Confirmado. On November 23, a letter appeared in the magazine Inédito complaining about the “Pop” experience. On December 7, an article appeared in the same magazine referring to the year’s artistic events, in which the work was mentioned.

There were probably other references to our work published in other magazines. We tried to get our report out to various types of publications: a daily newspaper, a magazine known for yellow journalism, a women’s magazine, a general information magazine, and a literary journal. Inédito and Confirmado accepted the news on their own, without any kind of information provided by us.

Regarding the way to “close the work,” we decided that we would consider it completed when the first articles appeared establishing that our report was untrue. This would include any reaction to those articles that may have been stimulated among news consumers. We didn’t have to wait too long for that reaction, which was systematized by a sociologist who ascertained some consumer reactions and wrote an article about our experience. He then personally distributed mimeographed copies of his article.

I Committed a Happening

By Oscar Masotta, 1967

Publication: Originally published as “Yo cometí un Happening,” in Oscar Masotta et al., Happenings (Buenos Aires: Editorial Jorge Álvarez, 1967)

Language: Spanish

When, in the December 16th edition of the newspaper La Razón, I read Professor Klimovsky’s condemnation of intellectuals who “concoct” Happenings, I felt directly and personally implicated. If I am not mistaken, the number of persons in Buenos Aires who fulfill such conditions can be counted on half the fingers of one hand. And since Klimovsky recommended “abstaining” from Happenings and “investing” the powers of the “imagination in lessening this tremendous plague” (of “hunger”), I have to admit, seriously, that I felt ill at ease, even a bit miserable. So I said, “I committed a Happening,” in order to quell this feeling.

But I was quickly able to regain my tranquility. The choice, “either Happenings or Left politics,” was false. At the same time, is Professor Klimovsky a man of the Left?122That he is not, in truth, would not prove much. The same prejudices with respect to this word—“Happening”—can be found in a marxist intellectual or party militant. Nor is it a matter of trying to disarm the adversary’s arguments by drawing attention to what he is not. I introduce the question of the Left here for expository reasons, to set things up more rapidly. It was enough to recall another either/or—of the same kind—that Klimovsky proposed in his prologue to a book by Thomas Moro Simpson,23Thomas Moro Simpson, Formas lógicas, realidad y significado (Buenos Aires: EUDEBA, 1964). where one reads: “We are much given to existentialism, phenomenology, Thomism, Hegelianism, and dialectical materialism; by contrast, analytic philosophy is almost absent from the curricula of our philosophy schools. . . . The causes of this state of affairs are diverse, reflecting the unusual preponderance in these latitudes of . . . certain religious or political traditions.” Finally, one must reply in the negative: No, Professor Klimovsky is not on the Left. First, because of the explicit tendency to assimilate the political to the religious, as we read in the preceding paragraph. Second, because in the context, when Klimovsky says “political” he directly denotes “dialectical materialism,” i.e., this philosophy of marxism. Third, because these two lines of assimilation seek only to persuade one of the truth of the false, right-wing choice: “either marxism or analytic philosophy.” And fourth, because it was anecdotally, i.e., historically, false that there existed at the moment when Klimovsky wrote this prologue, any preponderance in the teaching of the “marxist tendency” in Argentine lecture halls.

I said that the two choices are of the same kind: in both, one of the opposing terms does not belong to the same level of facts as the other. Analytical philosophy (the philosophy of science + modern logic + the analytic study of the problem of meaning) does not include any assertion about the development of history, about the origin of value in labor, about the social determination of labor, or finally about the social process of production or about the necessity of revolution that can be read in this process. It could then additionally be said that insofar as marxism includes proposals concerning the origin, value, and scope of ideas, for example, it includes analytic philosophy, while the reverse is impossible. Marxism can certainly integrate the results of the analytic study of propositions and strengthen its methodology with the contributions of the logic and philosophy of science; while, on the contrary, if analytic philosophy claimed to include marxism, it would simply dissolve eighty percent of the assertions of marxism, which, being proposals about society as a whole and about the totality of the historical process, are effectively synthetic, if not dogmatic.24Dogmatic in the positive sense of the word. This is what Sartre sees at the outset of his “critical” investigation of “dialectical reason.” But in the reverse, one must certainly take care not to make marxism into a romantic philosophy of totality and synthesis. The category of totality, its indiscriminate use, has more to do with a specifically spiritualist philosophy than with the strict discipline demanded by the marxist idea of “science.” We then see that there exist two perspectives from which to look upon the relation between marxism and the philosophy of science. If one does so from the viewpoint of marxism, there is no exclusive choice, but a relation of inclusion and complementarity. If, on the other hand, we look from the viewpoint of the philosophy of science, the terms become contradictory and the choice is exclusive.