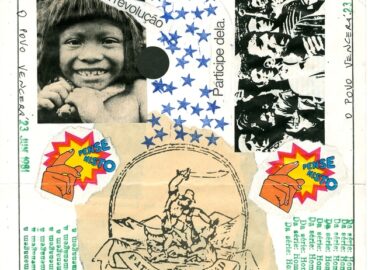

Mail art celebrates a fissure in the system and, in fact, mocks its methods of silencing and control, creating opportunities for direct communication without manipulative intermediaries.

This text, authored by Colectivo 3, was disseminated as part of the ongoing project of the Poema Colectivo: Revolución, in 1982. It sheds light on the strategies and ideas that instigated the Poema Colectivo and delineates the tactical advantages of communicating and sharing art through the mail. The piece comments on the development of “localized circuits of communication” that contrast with the circulation of the homogenized mass media.

Mail Art: Poetry and Communication

By Colectivo 3, 21 January, 1982

Publisher: Self-published by Colectivo 3

Language: Spanish

The mail art (or postal art) movement is currently made up of several hundred participants from various countries in the capitalist world as well as in the Socialist bloc and the so-called Third World. Thought to have been initiated by the American Ray Johnson, the movement today attracts offerings from people of extremely diverse occupations and professions. Mail art is integral to the practice of several well-known artists, and there are signs of its growing assimilation by the market and cultural establishment.

How can we define mail art? One of its basic characteristics is the channel of communication it employs to distribute its messages: the mail, that is, official postal services, although networks such as the telegraph, telephone, telex and computers have also come to be used. But given its principal focus on the postal system, this art also frequently adopts the formats and symbols associated with the mail: envelope borders, stamps, rubber stamps resembling official postmarks, postcards, and so on.

This emphasis on postal communication is in itself significant. Despite certain well-known restrictions that can lead to interception and censorship, the mail is a medium of communication available to anyone; it is comparatively cheaper than practically any other means of circulation. Today, in the face of the dense web of police and monopolized surveillance and the prohibitive costs and censors that condition the means of collective expression, the mail represents an open space of communication. Thus, mail art celebrates a fissure in the system and, in fact, mocks its methods of silencing and control, creating opportunities for direct communication without manipulative intermediaries.

The characteristics mentioned above impose certain physical and formal characteristics on the works. To begin with, the materials used must be extremely lightweight, lending themselves to the concise communication of ideas. Often, the works should be able to be reproduced or even mass-produced, since their makers pay the costs of producing and posting the works themselves. This is another of the unwritten, pragmatic, and significant rules of mail art.

A defining characteristic emerges, then: an intentionality, which leads to a certain degree of systematization. That is to say that, in contrast to the sender of a regular letter, or even of an ‘”artistic”’ communication (whether literary or from the visual arts), the mail art practitioner recognizes the existence of specific “‘languages’,” approaches, and interlocutors. In this way, an ad hoc communication circuit is formed, with aesthetic roots and specific objectives, although the latter are both implicit and polysemous.

Undoubtedly, this very quality of a special circuit entails a limitation: it is a strictly selective exchange. The letters are written to “equals,” so to speak, although usually the artist and recipients are not personally acquainted. It is possible that this limitation could be overcome, as will be seen below, but for now we can consider at least two factors that expand the reach of the circle:

1) Mail art entails a long-distance dialogue between individuals who will perhaps never meet or exchange perspectives face-to-face. Thus, it breaks down parochialisms and narrow-mindedness; it allows people to come into contact with unfamiliar circumstances and problems, encouraging comprehension and solidarity.

2) Correspondingly, the very nature of the system means that it is a political and ideological dialogue. It is true that mail art often becomes an outlet for escapist imaginings, but this always represents the exercise of freedom (within socio-political limitations). It should be noted that mail art emphatically favors practices of self-expression, and that this is one of its most productive possibilities.

This last point needs to be underscored. If conceived of at a social level, with broad participation, this self-expressive impulse could break down the barrier of transactions limited to collectors and connoisseurs. It would be necessary to teach, to dedicate attention to promoting the emergence of localized circuits of communication—that is to say, circuits controlled by the senders and recipients—that would flow through all levels of society, different from and surely in contrast to the homogenizing, repressive codes of mass culture and mass media.

This returns us to the question of formal characteristics, particularly the means of material production. In mail art, artisanal practices are championed and combined with modern technological inventions, but under the control of the producers. Functioning in terms alien to both the market and government subsidies, these works employ forms that are economical and able to be reproduced by means of offset presses, photocopiers, photo-mechanical printers, mimeograph machines, serigraphs, engravings, rubber stamps, etc. The idea is that many people, or social groups, can work with the resources they have on hand, which entails a formal and economic democratization of production.

Does mail art constitute a new “avant-garde,” or a fad? The answer is no. Viewed as a circuit of horizontal and open communication, it escapes the official “boxes” of art. Yet it gathers together all the artistic contributions of this century—Constructivism, Futurism, Art Informel, Conceptual art, Pop art, Arte Povera, environmental art, systems art, Action art, and more—into a “stew” that is admittedly eclectic but that focuses on dialogic communication, on dialogue. In this sense, its degree of aesthetic innovation is low, while its participatory capacity is high and corrosive.

Mail artists themselves prefer not to define their practice. Little has been written or theorized about their work; the trend stems from a desire to break with rhetorical convention (although other rules are created) even if these practices, as new processes of signification, occupy a place within the frameworks of ideological and cultural semiotics. Today, given the profusion of practitioners and internal currents within the mail art movement, it is appropriate to analyze and order it as a system in order to increase its potential as an artistic and political response. In summary, with no barriers to its production, reproduction or dissemination, it represents art fulfilled: MAIL ART.

Mexico, Districto Federal, 21 January, 1982

[Spanish version follows]

Arte Correo: Poética y Comunicación

El movimiento de arte-correo o arte postal incorpora actualmente a varios cientos de productores de diversos países, tanto del ámbito capitalista como del bloque socialista y del llamado Tercer Mundo. Iniciado, según se presume, por el estadunidense Ray Johnson, ahora da pábulo para que personas de muy disímiles ocupaciones y profesiones ofrezcan sus propuestas. Asimismo, lo practican algunos artistas de renombre y llegan a darse visos de su asimilación por el mercado y los aparatos del establecimiento cultural.

¿Cómo puede definirse al arte-correo? Una característica básica está dada por el tipo de canal de comunicación que utiliza para distribuir sus mensajes: el postal, esto es, los sistemas oficiales de correo, si bien eventualmente se recurre a la red telegráfica, telefónica, télex, terminal de computadora, entre otros. Pero vista la primacía del sistema postal, también asume la simbología del correo en muchas ocasiones: orlas de sobres, estampillas, sellos de hule similares a los de resello, tarjetas postales y demás.

Ese mismo acento prestado a la forma de envío postal resulta significativo. A despecho de ciertas restricciones consabidas y ecuménicas, como son la censura o la violación de la correspondencia, el correo es todavía un medio de comunicación al alcance de cualquier persona y, comparativamente, más barato que prácticamente todos los restantes medios de difusión. Hoy, ante la espesa trama de controles monopólicos y policíacos, costos prohibitivos y expertos de la manipulación que condicionan a los medios de significación colectiva, ciertamente el correo representa un espacio abierto de comunicación. Así, por ende, el arte-correo reivindica una fisura del sistema y burla, de hecho, sus mecanismos de acallamiento y control, dando oportunidad al trato directo y sin intermediarios manipuladores.

La característica anterior involucra ciertas condicionantes hacia el aspecto formal de las producciones. En principio, los soportes materiales deben ser en extremo ligeros, susceptibles de recoger planteamientos muy sintéticos y, probablemente, de reproducción múltiple o en serie. Esto, a su vez, proviene del hecho de que los productores sufragan por su cuenta el envio de sus trabajos y los costos de reproducción, lo cual constituye otra de sus reglas no escritas, pragmáticas y significativas.

De lo visto se desprende una característica definitoria: la intencionalidad, que también apareja un cierto grado de sistematización. Es decir, a diferencia de una carta común, o incluso de una correspondencia “artística” – literaria o plástica –, el practicante del arte-correo reconoce la existencia de “lenguajes”, planteamientos e interlocutores específicos. Configura, así, un circuito ad hoc de comunicación, con raíces estéticas y objetivos determinados, si bien implícitos y polisémicos.

Sin duda, esa misma calidad de circuito especial entraña una limitación: un intercambio estrictamente selectivo. Se escribe a iguales, por decir así, aunque las más veces no haya conocimiento personal. Creemos que esta limitación podrá subsanarse, como veremos a continuación, pero, por lo pronto, cabe apreciar al menos dos factores que amplían los alcances del circuito:

1) Un diálogo a larga distancia, entre individuos que quizás nunca llegarían a conocerse ni a intercambiar concepciones. Esto rompe los parroquialismos, la estrechez de miras, permite conocer otra circunstancia y otra problemática. Nutre la comprensíon y la solidaridad.

2) Correlativamente, se trata de un diálogo político, ideológico, por la propia naturaleza del sistema. Muchas veces estimula desfogues escapistas, es cierto, pero siempre significa un ejercicio libre (dentro de las grandes limitaciones sociopolíticas). Cabe decir, recargando el término, que favorece las prácticas de autoexpresión, y éste es uno de sus potenciales más productivos.

Insistiríamos sobre este último punto. Proyectado socialmente, masivamente, aquel acicate a la autoexpresión podría romper la barrera de trato circunscrito a conocedores o coleccionistas. Sería preciso enseñar, orientarse a promover el surgimiento de circuitos localizados de comunicación — es decir, controlados por los emisores y los receptores –, que fluyan a través de todos los estratos de la sociedad, diferentes y seguramente contrapuestos a los códigos uniformadores, represivos, de la cultura y la comunicación masiva dominantes.

Lo visto nos lleva nuevamente a las características formales, principalmente los medios de producción material. Aquí se reivindican las prácticas artensanales combinadas con los modernos ingenios tecnológicos, pero bajo el control de los productores. Al desempeñarse en términos ajenos al mercado y al subsidio gubernamental, estas manifestaciones acuden a hechuras económicas y de reproducción múltiple: ofsset de oficina, fotocopiadora, fotomecánica, mimeógrafo, serigrafía, grabado y sellos de goma, collage, etc. Se trata de que muchas persenas, o grupos sociales, puedan hacer las cosas con los recursos a su alcance, lo cual conlleva una democratización económica y formal de las producciones.

¿Constituye una nueva “vanguardia”, o una moda, el arte-correo? No, de hecho. Visto como un circuito de comunicación abierta, horizontal, escapa a los cartabones oficiales del arte. Sin embardo, recoge todas las aportaciones artísticas de este siglo — constructivismo, futurismo, informalismo, arte conceptual, pop, pobre, ecológico, de sistemas, actuaciones y demás — en un “caldo” ecléctico, sí, pero dirigido sobre todo a la comunicación dialógica, al diálogo. En este tenor, su novedad estética es baja, mientras su capacidad participativa es alta y corrosiva.

Por su parte, los artecorreístas no gustan de definir su práctica. Poco se ha escrito o teorizado al respecto; priva un afán de romper las normas retóricas (aunque se crean otras reglas), si bien, en calidad de nuevos procesos de significación, ocupa un lugar en los marcos de la semiótica ideológica y cultural. Hoy, dada la profusión de practicantes y de corrientes internas en el movimiente, es oportuno intentar analizarlo y ordenario como un sistema, que eleve sus potenciales de respuesta artística y política. En suma, sin barreras para producirlo, reproducirlo y trasmitirlo, se trata del arte realizado: POST-ARTE.

México, D.F., 21 de enero/82