Curator Christine Macel traces the connections between Brazilian artist Lygia Clark’s fascination with psychoanalysis and subsequent exploration of the body and mind in art. Part three of this essay explores the influential psychoanalytical sources that Clark integrated into her art and therapy practices.

In addition to Macel’s commentary, you can access installation views and the press release in MoMA’s comprehensive online exhibition history archive here.

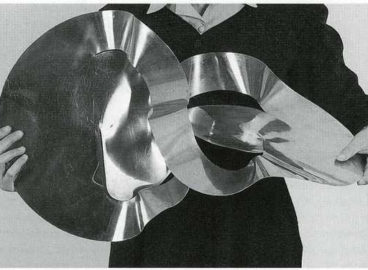

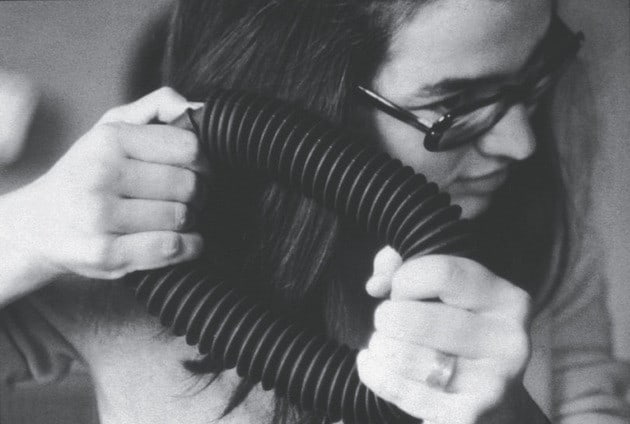

Clark’s work sketched out a path to moving beyond the idea of an autonomous object in an attempt to surpass the subject-object relationship, with the aim of putting the body back at the center of an art experiment, such that the turning point of the mid-1970s, when she returned to Brazil, seemed to follow naturally from the previous period. From 1976 to 1984, the objects she used shifted from being “sensory” to being “relational,” as part of a true therapeutic treatment aimed at structuring the self. At her Rio residence she saw “clients” three times a week, offering one-hour sessions over the course of varying lengths of treatment. They were placed in a state of regression back to a primal stage, while Clark used her objects to work with them on the body’s fantasy dimension. Her practice, which was now on the fringes of art, was nevertheless based on objects created from the mid-1960s on, and those objects had no other existence than their activation through the therapeutic treatment. Clients were invited to lie down on the Grande colchão (Large mattress) full of styrofoam balls. Clark used various objects, such as stones placed on different parts of the body, or fabrics, from veils to blankets; she also offered cushions filled with heavier or lighter objects, objects made from stockings containing different materials (balls, stones, shells), and plastic bags filled with air, water, or sand. Some were the product of her earlier experiments with sensory objects, like Respire comigo. Others, such as a long cardboard tube, had been used in acts at the Sorbonne — in this case Relaxação, a collective act from 1974–75 similar to the therapeutic protocol. Heavy or light, quiet or noisy, hot or cold, the object moved over the client’s body, was used or even destroyed, like a plastic bag she suggested they pop — or not. Some objects, like honey, could even be incorporated into the body. A stone held in the palm of the hand served as a proof of reality. Stripped of any intrinsic qualities, the object became the “target of acting out for the subject manipulating it,” in a loving or destructive process,1Emphasis mine, to underscore Clark’s use of psychoanalytical vocabulary. Clark, “Relational Object,” 1980, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 320. Translation modified. In this text she cites Winnicott as an explicit reference. in a sort of preverbal language, sometimes accompanied by words on the subject of the lived experience, the fantasy brought to life within each person — for it was the fantasy of the body that interested her, not the body itself.2Clark, letter to Oiticica, July 6, 1974, p. 288.

Through this therapeutic approach, which sprang from her art, her own experience of therapy, and her knowledge of psychoanalysis, Clark proclaimed her curative intent, targeting the types of pathologies that interested her and that best fit her method. Borderline states,3In a letter to Brett in 1983: “I only like working with borderline cases. The neurotic is very defensive. . . . I often say: ‘Never deal with a psychotic as a sick person, but rather as an artist without work.” Clark, letter to Brett, October 14, 1983, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 338. unstructured places on the border between neurosis and psychosis, and psychotics, whose denial of reality pushed them to dissociate, were better able to respond, according to her, to a “massive maternalization” (unlike neurotics, who were caught up in repression), “personal contact and not classic analytical interpretation,” and thus to “intensify” their “primal anxieties.”4Clark, “The Structuring of the Self,” 1980, in ibid., pp. 321, 22 (translation modified). Without judging the effectiveness of these unorthodox courses of treatment — which Clark and Lula Wanderley, an artist and psychotherapist trained in her methods, claimed were truly effective — we see that this experimentation is echoed in a questioning of the system of psychoanalytic treatment itself. Reconsidered in the 1950s by Winnicott, and then by psychoanalysts such as Anzieu and Green, the analytic framework had been adapted to address an increase in new pathologies and their resistance to cure by classical Freudian psychoanalysis. Refocusing on the body through contact (although touch was still a psychoanalytical taboo) led Clark to explore issues typical of her time that today have become the subjects of new developments.

Two intuitions can be seen throughout her experimentation: first, a conception of the subject based on a bodily self whose skin, like an envelope, is the border; and second, a true cognitive unconscious, or an unconscious memory of the body, originating at the preverbal stage. In a 1992 seminar held in Rio de Janeiro, Wanderley noted that the objects Clark used “always had a film covering something inside. . . . Always that material and inner motion which produced a sensory feel, as though the sensory was not something superficial, but rather internal. . . . It reminds me a little of the body, too; our skin, motion. . . . There is a certain analogy with this thing that envelops people, but in a primitive way.”5Lula Wanderley, at a seminar on Clark, Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, March 11, 1992. Archives of the Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark,” Rio de Janeiro. My translation from the Portuguese.

Indeed, Clark thought of the subject first and foremost in its corporeal dimension, as a surface that delimited an internal space. The objects she put into contact with the body were also conceived as following the model of envelope and container, acting as metaphors for the internal corporeal self on the outside of the body, offering a surface for projection and fantasizing. In Mário Carneiro’s film Memória do corpo (Memory of the body, 1984), a client of Clark’s describes his experience as follows: “Each time [things] moved over me, I was above all skin, above all a surface . . . . [And the surface] is the place where we are with the world . . . . I did not exist inside . . . . And suddenly, honey filled me, filled me inside.” The concept of a “Self-Skin” appeared in psychoanalytic thought shortly before the start of Clark’s therapeutic practice, in Anzieu’s famous text “Le Moi-Peau” (The skin ego) from 1974.6Didier Anzieu, “Le Moi-Peau,” in Le Dehors et le dedans, Nouvelle revue de psychanalyse no. 9 (Spring 1974):195–208. See also Anzieu, Le Moi-Peau (Paris: Dunod, 1995). By the 1960s psychoanalytic thinkers had already developed ideas of the self as a container, notably Winnicott in his concept of “holding” (the way a mother holds her child) and Esther Bick in her “Experience of the Skin in Early Object Relations” (1968), both starting from a Freudian conception of the self as a psychic envelope supported by the bodily envelope.7In 1923 Sigmund Freud developed the concept of the body ego, according to which the ego is like a surface, an interface between the inside and outside worlds. “The ego is first and foremost a bodily ego: it is not merely a surface entity, but is itself the projection of a surface.” Sigmund Freud, The Ego and the Id (New York: W. W. Norton, 1990), p. 20. For Anzieu — though it is unclear if Clark has read his work when she was starting out — the skin ego is a containing envelope, like a bag, a screen, or a sieve. The subject constructs itself by basing itself on the body and on the object. The dimension of touch seems crucial in constructing a psychic envelope, but we must also consider the auditory, visual, and olfactory envelope (which Clark accomplished through her multisensory objects). Consequently, the therapy that arose from such thinking particularly stressed the model of the container and worked to unify the self and the body, in order to shore up a psychic envelope that was both receptive and flexible but also solid, and could contain internal objects and act as a shield against external forces that might threaten to overexcite.

In her treatment Clark also worked, in her own words, on “body memory . . . the affective memory . . . bringing experiences which the verbal aspect cannot detect.”8Clark, “Memory of the Body,” in Lygia Clark(Barcelona), p. 326. This idea of the body’s unconscious memory has been the subject of a great deal of joint research between psychoanalysis and the neurosciences, which only managed to pinpoint its existence in the late 1990s. Today we have identified “the implicit memory, which does not allow us to remember it, while the structures of explicit memory, which is indispensable for repression, only form after the age of two,” because “the hippocampus and the medial temporal cortex are not definitively formed.”9Mauro Mancia, “Mémoire implicite et inconscient précoce non refoulé: Leur rôle dans le transfert et le rêve,” in Neuroscience et psychanalyse, Revue française de psychanalyse 71, no. 2 (April 2007):369. The implicit memory is located in the amygdala, the emotion organ, and allows for “the return of the non-repressed by other paths than memory,” paths that Clark widely explored. Implicit memory is written in the body, and some see it as including “tastes, habits, ways of behaving, casts of mind.”10Bernard and Bianca Lechevallier, “Aborder la question de la conscience,” Revue française de psychanalyse 71, no. 2 (April 2007):447, citing Larry R. Squire and Eric R. Kandel, Memory: From Mind to Molecules (1999). So we could speak of a cognitive unconscious, according to the neuropsychologist Francis Eustache, in which implicit memory plays a central part, which could parallel the unconscious described by psychoanalysis.11Ibid., p. 443.

In light of these fundamental intuitions and despite the unorthodox style of her treatment, Clark surely had her finger, so to speak, on major issues involving pathology and its therapies. Nevertheless, her borderline practice, on the edges of psychoanalysis (a boundary she continually played with in her life and her art), has never been recognized, despite the therapeutic success affirmed by Clark herself and the people she trained, such as Wanderley and Gina Ferreira, and despite her efforts to pass down her work so that it could endure.12In the film Memória do corpo she says, “I first started to do this work nine years ago, and my first concern was to transmit this work, through fear of dying and of having done work that would never be applied.” Psychologists and psychoanalysts have held her practice at arm’s length, as has the art world, aside from the Brazilian critics Pedrosa and Frederico Morais.13See Rolnik, “Entretien avec Suely Rolnik par Jennifer Lacey,” Le Journal des laboratoires, Laboratoire d’Auber-villiers (May–August 2012), available online at www.leslaboratoires.org/en/article/entretien-avec-suely-rolnik/i-heart-lygia-clark. The Neo-Concretist theorist Ferreira Gullar was particularly critical of her last period, while most art historians, like Brett and Yve-Alain Bois, maintain that to them, she always remained an artist. Bois, who had been close to Clark since his adolescence, and whom she had directed to read Winnicott, remains reserved about her art therapy and suspends his judgment on what seems to him clearly not art but therapy.14See Yve-Alain Bois in Jane de Almeida, “Interview with Yve-Alain Bois,” July 2, 2005, Harvard University: “I call the late work the work she did after [La Sorbonne], which is therapy. That’s the one I don’t quite really know what to do with.” Available online at www.janedealmeida.com/yve_alain_bois.pdf.

The psychoanalyst and cultural critic Suely Rolnik views Clark’s work as something between art and psychoanalysis, or a tension between the two — a hybrid that is neither psychoanalysis nor art.15See Rolnik, “The Hybrid of Lygia Clark,” in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 344. In a letter quoted by Rolnik, Clark explained, “I did not swap art for psychoanalysis. It just happened that in all my research I ended up doing what I do, which is not psychoanalysis. Since I asked for the spectator’s participation, which was in ’59, all of my work has demanded the spectator’s participation; my work has always been led toward experimentation by others, not only for my own experience.”16Clark, unpublished letter to Madame Karlicow, quoted in ibid., p. 347. Since Clark was always mistrustful of categories — or, as Fédida said, in a state of “insecurity” toward them — doubtless she might have agreed with Rolnik’s analysis. However, it seems that “on the path of her work,” she moved beyond both art and psychoanalysis, rather than creating a hybrid of the two.17Fédida, in an interview with Rolnik, “Ne pas être en repos avec les mots. Entretien avec Pierre Fédida,” Lygia Clark: De l’oeuvre à l’événement, exh. cat. (Nantes: Musée des Beaux Arts de Nantes, 2005), p. 69. Indeed, her interests and intuitions on “the edges of psychoanalysis” went beyond the narrow confines of that field and met up with the more recent, still developing fields of the phenomenology of perception, the psychology of perception, the cognitive sciences, and even neuropsychoanalysis.18Clark, “The Phantasmagoria of the Body,” in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 314.

With her endless explorations of the idea of borders, the inside and the outside, it is not surprising that Clark’s art, like her therapeutic practice, should be borderline, neither/nor, at the edges of art, psychoanalysis, and the cognitive sciences, both of its day and ahead of its time. Where art and therapy came together was doubtless in her desire for the gift, in an openness to others and the wish to help them express themselves. “I always thought it was fabulous to have given something of my art for someone to express themselves,” she confided to Oiticica.19Clark, letter to Oiticica, November 14, 1968, Eng. trans. in ibid., a translation reprinted in the present volume, p. 232. The whole of Clark’s life and art were turned toward the invention of a new way of being in good health, for herself and for others — not the health of normalcy or adaptation to the norm, but a kind of health that can be picked up implicitly through the borderline pathologies that interested her so much. Unlike research on power or submission, that type of individual health — an aesthetic but also a political project, never stable and always at the edges — was based on fundamental values of art, spontaneity, intuition, and the creative space.

This is the third and final section of an essay by Christine Macel on the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, excerpted from the exhibition catalog Lygia Clark: The Abandonment Of Art, 1948-1988, available at the MoMA bookstore. Read the first section here and the second section here.

- 1Emphasis mine, to underscore Clark’s use of psychoanalytical vocabulary. Clark, “Relational Object,” 1980, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 320. Translation modified. In this text she cites Winnicott as an explicit reference.

- 2Clark, letter to Oiticica, July 6, 1974, p. 288.

- 3In a letter to Brett in 1983: “I only like working with borderline cases. The neurotic is very defensive. . . . I often say: ‘Never deal with a psychotic as a sick person, but rather as an artist without work.” Clark, letter to Brett, October 14, 1983, in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 338.

- 4Clark, “The Structuring of the Self,” 1980, in ibid., pp. 321, 22 (translation modified).

- 5Lula Wanderley, at a seminar on Clark, Museu de Arte Moderna, Rio de Janeiro, March 11, 1992. Archives of the Associação Cultural “O Mundo de Lygia Clark,” Rio de Janeiro. My translation from the Portuguese.

- 6Didier Anzieu, “Le Moi-Peau,” in Le Dehors et le dedans, Nouvelle revue de psychanalyse no. 9 (Spring 1974):195–208. See also Anzieu, Le Moi-Peau (Paris: Dunod, 1995).

- 7In 1923 Sigmund Freud developed the concept of the body ego, according to which the ego is like a surface, an interface between the inside and outside worlds. “The ego is first and foremost a bodily ego: it is not merely a surface entity, but is itself the projection of a surface.” Sigmund Freud, The Ego and the Id (New York: W. W. Norton, 1990), p. 20.

- 8Clark, “Memory of the Body,” in Lygia Clark(Barcelona), p. 326.

- 9Mauro Mancia, “Mémoire implicite et inconscient précoce non refoulé: Leur rôle dans le transfert et le rêve,” in Neuroscience et psychanalyse, Revue française de psychanalyse 71, no. 2 (April 2007):369.

- 10Bernard and Bianca Lechevallier, “Aborder la question de la conscience,” Revue française de psychanalyse 71, no. 2 (April 2007):447, citing Larry R. Squire and Eric R. Kandel, Memory: From Mind to Molecules (1999).

- 11Ibid., p. 443.

- 12In the film Memória do corpo she says, “I first started to do this work nine years ago, and my first concern was to transmit this work, through fear of dying and of having done work that would never be applied.”

- 13See Rolnik, “Entretien avec Suely Rolnik par Jennifer Lacey,” Le Journal des laboratoires, Laboratoire d’Auber-villiers (May–August 2012), available online at www.leslaboratoires.org/en/article/entretien-avec-suely-rolnik/i-heart-lygia-clark.

- 14See Yve-Alain Bois in Jane de Almeida, “Interview with Yve-Alain Bois,” July 2, 2005, Harvard University: “I call the late work the work she did after [La Sorbonne], which is therapy. That’s the one I don’t quite really know what to do with.” Available online at www.janedealmeida.com/yve_alain_bois.pdf.

- 15See Rolnik, “The Hybrid of Lygia Clark,” in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 344.

- 16Clark, unpublished letter to Madame Karlicow, quoted in ibid., p. 347.

- 17Fédida, in an interview with Rolnik, “Ne pas être en repos avec les mots. Entretien avec Pierre Fédida,” Lygia Clark: De l’oeuvre à l’événement, exh. cat. (Nantes: Musée des Beaux Arts de Nantes, 2005), p. 69.

- 18Clark, “The Phantasmagoria of the Body,” in Lygia Clark (Barcelona), p. 314.

- 19Clark, letter to Oiticica, November 14, 1968, Eng. trans. in ibid., a translation reprinted in the present volume, p. 232.